- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

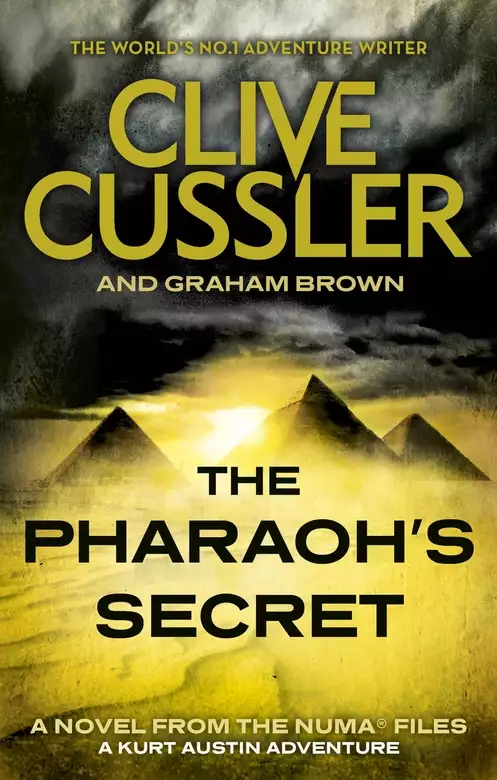

A Kurt Austin NUMA files adventure, The Pharaoh's Secret is a gripping, action-packed and suspense-filled tale that delves into the mysteries of Ancient Egypt and is set in and beside the sparkling Mediterranean Sea.

A deadly poison

On the Mediterranean island of Lampedusa a mysterious ship runs aground, explodes and releases a poisonous black mist. As the island's inhabitants fall where they stand, someone sends a distress call.

A rescue mission

Kurt Austin and the NUMA team are diving for antiquities when they pick up the call. As the only vessel for hundreds of miles, they attempt to rescue survivors. But something is very wrong about this incident.

A secret conspiracy

Tasked with finding who might be responsible, Kurt uncovers a secretive organization that is using the knowledge and power of the Ancient Egyptians to destabilize northern Africa.

If he doesn't find out why and how to stop them, millions will die . . .

Praise for Clive Cussler

'Cussler is hard to beat'

Daily Mail

'Clive Cussler is the guy I read'

Tom Clancy

'The Adventure King'

Daily Express

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 120000

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Pharaoh’s Secret

Clive Cussler

The full moon cast a blue glow across the sands of Egypt, painting the dunes the color of snow and the abandoned temples of Abydos in shades of alabaster and bone. Shadows moved beneath this stark illumination as a procession of intruders crept through the City of the Dead.

They traveled at a somber pace, thirty men and women, their faces covered by the hoods of oversize robes, their eyes locked on the path before them. They passed the burial chambers containing the pharaohs of the First Dynasty and the shrines and monuments built in the Second Age to honor the gods.

At a dusty intersection, where the drifting sand covered the stone causeway, the procession came to a silent halt. Their leader, Manu-hotep, gazed into the darkness, cocking his head to listen and tightening his grip on a spear.

“Did you hear something?” a woman asked, easing up beside him.

The woman was his wife. Behind them trailed several other families and a dozen servants carrying stretchers that bore the bodies of each family’s children. All cut down by the same mysterious disease.

“Voices,” Manu-hotep said. “Whispers.”

“But the city is abandoned,” she said. “To enter the necropolis has been made a crime by Pharaoh’s decree. Even we risk death to set foot on this ground.”

He pulled back the hood of his cloak, revealing a shaven head and a golden necklace that marked him as a member of Akhenaten’s court. “No one is more aware of that than I.”

For centuries, Abydos, the City of the Dead, had thrived, populated by priests and acolytes of Osiris, ruler of the afterlife and the god of fertility. The pharaohs of the earliest dynasty were buried here, and though more recent kings had been buried elsewhere, they still constructed temples and monuments to honor Osiris. All except Akhenaten.

Shortly after becoming pharaoh, Akhenaten had done the unthinkable: he’d rejected the old gods, minimizing them by decree and then overthrowing them, casting the Egyptian pantheon down into the dust and replacing it with the worship of a single god of his choosing: Aten, the Sun God.

Because of this, the City of the Dead was abandoned, the priests and worshippers long gone. Anyone caught within its borders was to be executed. For a member of Pharaoh’s court like Manu-hotep, the punishment would be worse: unrelenting torture until they prayed and begged to be killed.

Before Manu-hotep could speak again, he sensed movement. A trio of men came racing from the dark, weapons in hand.

Manu-hotep pushed his wife back into the shadows and lunged with his spear. It caught the lead man in the chest, impaling him and stopping him cold, but the second man stabbed at Manuhotep with a bronze dagger.

Twisting to avoid the blow, Manu-hotep fell to the ground. He pulled his spear free and slashed at the second assailant. He missed, but the man stepped backward and the tip of a second spear came through his back and protruded from his stomach as one of the servants joined the fight. The wounded man crumpled to his knees, gasping for air and unable to cry out. By the time he fell over, the third assailant was running for his life.

Manu-hotep rose up and flung his spear with a powerful twist of his body. It missed by inches and the fleeing target disappeared into the night.

“Grave robbers?” someone asked.

“Or spies,” Manu-hotep said. “I’ve felt as if we were being followed for days. We need to hurry. If he gets word to Pharaoh, we won’t live to see the morning.”

“Perhaps we should leave,” his wife urged. “Perhaps this is a mistake.”

“Following Akhenaten was the mistake,” Manu-hotep said. “The Pharaoh is a heretic. Because we stood with him, Osiris punishes us. Surely you’ve noticed that only our children fall asleep, never to wake; only our cattle lie dead in the fields. We must beg Osiris for mercy. And we must do it now.”

As Manu-hotep spoke, his determination grew. During the long years of Akhenaten’s reign, all resistance had been crushed by force of arms, but the gods had begun taking revenge of their own and those who stood with Pharaoh were suffering the worst.

“This way,” Manu-hotep said.

They continued deeper into the quiet city and soon arrived at the largest building in the necropolis, the Temple of Osiris.

Broad and flat-roofed, it was surrounded by tall columns sprouting from huge blocks of granite. A great ramp led up to a platform of exquisitely carved stone. Red marble from Ethiopia, granite infused with blue lapis from Persia. At the front of the temple stood a pair of mammoth bronze doors.

Manu-hotep reached them and pulled the doors open with surprising ease. The smell of incense wafted forth, and the sight of fire in front of the altar and torches on the walls surprised him. The flickering light revealed benches arranged in a semicircle. Dead men, women and children lay upon them, surrounded by members of their own families and the muted sounds of quiet sobbing and whispered prayers.

“It appears we’re not the only ones to break Akhenaten’s decree,” Manu-hotep said.

Those inside the temple looked at him, but otherwise they didn’t react.

“Quickly,” he said to his servants.

They filed in, placing the children’s bodies where they could find space as Manu-hotep approached the great altar of Osiris. There, he knelt, head down beside the fire, bowing in supplication. He withdrew from his robe two ostrich feathers.

“Great Lord of the Dead, we come to you in suffering,” he whispered. “Our families have fallen to the affliction. Our houses have been cursed, our lands have turned to worthless chaff. We ask that you take our dead and bless them in the afterlife. You who control the Gates of Death, you who command the rebirth of the grain from the fallen seed, we beseech you: send life back to our lands and homes.”

He placed the feathers down reverently, sprinkled a mixture of silica and gold dust across them and stepped back from the altar.

A gust of wind blew through the chamber, drawing the flames to one side. A resounding boom followed and echoed throughout the hall.

Manu-hotep spun just in time to see the huge doors at the far end of the temple slam shut. He looked around nervously as the torches on the wall flickered, threatening to go out. But they stayed lit and the flames soon straightened and burned brightly once again. In the restored light, he saw the shape of several figures behind the altar where no one had been standing just moments before.

Four of them were dressed in black and gold—priests of the Osiris cult. The fifth was clothed differently, as if he were the Lord of the Underworld himself. The fabric used to mummify the dead had been wrapped around his legs and waist. Bracelets and a necklace of gold contrasted with his greenish-tinted skin, while a crown replete with ostrich feathers adorned his head.

In one hand this figure held a shepherd’s crook, in the other a golden flail, meant to thrash the wheat and separate the living grain from the dead husk. “I am the messenger of Osiris,” this priest said. “The avatar of the Great Lord of the Afterlife.”

The voice was deep and resonant and almost otherworldly in its tone. Everyone in the temple bowed and the priests on either side of this central figure proceeded forth. They walked around the dead scattering leaves, flower petals and what looked to Manuhotep like dried skin from reptiles and amphibians.

“You seek the comfort of Osiris,” the avatar said.

“My children are dead,” Manu-hotep replied. “I seek favor for them in the afterlife.”

“You serve the betrayer” was the response. “As such, you are unworthy.”

Manu-hotep kept his head down. “I have allowed my tongue to do Akhenaten’s work,” he admitted. “For that, you may strike me down. But take my loved ones to the afterlife as they had been promised before Akhenaten corrupted us.”

When Manu-hotep dared to look up, he found the avatar staring at him, its black eyes unblinking.

“No,” the lips said finally. “Osiris commands you to act. You must prove your repentance.”

A bony finger pointed toward a red amphora resting on the altar. “In that vessel is a poison that cannot be tasted. Take it. Place it in Akhenaten’s wine. It will darken his eyes and deprive him of sight. He will no longer be able to stare at his precious sun and his rule will crumble.”

“And my children?” Manu-hotep asked. “If I do this, will they be favored in the afterlife?”

“No,” the priest said.

“But why? I thought you—”

“If you choose this path,” the priest interrupted, “Osiris will command your children to live in this world once again. He will turn the Nile back to a River of Life and allow your fields to become fertile. Do you accept this honor?”

Manu-hotep hesitated. To disobey the Pharaoh was one thing, but to assassinate him . . .

As he wavered, the priest moved suddenly, thrusting one end of the flail into the fire beside the altar. The leather strands of the weapon burst into flame as if they were covered in oil. With a snap of his wrist, the priest flicked the weapon downward into the dead husks and leaves scattered by his followers. The dried chaff lit instantly and a line of fire raced along the trail until a circle of flame surrounded both the living and the dead.

Manu-hotep was forced back by waves of heat. The smoke and fumes became overpowering, blurring his vision and affecting his balance. When he looked up, a wall of fire separated him from the departing priests.

“What have you done?” his wife cried out.

The priests were vanishing down a stairwell behind the altar. The flames were chest-high and both the mourners and the dead were now trapped in a circular blaze.

“I hesitated,” he muttered. “I was afraid.”

Osiris had given them a chance and he’d thrown it away. In mental agony, Manu-hotep glanced at the amphora of poison on the altar. It blurred in the heat and then vanished from sight as the smoke overcame him.

Manu-hotep woke up to a stream of light pouring in through open panels in the ceiling. The fire was gone, replaced by a circle of ashes. The smell of smoke lingered and a thin layer of residue could be seen on the floor as if the morning dew had mixed with the ash or perhaps a thin, misty rain had fallen.

Groggy and disoriented, he sat up and looked around. The huge doors at the end of the room were open. The cool morning air was wafting through. The priests hadn’t killed them after all. But why?

As he searched for a reason, a small hand with tiny fingers trembled beside him. He turned to see his daughter, shaking as if in a seizure, her mouth opening and closing as if she was fighting for air like a fish on the riverbank.

He reached for her. She was warm instead of cold, moving instead of rigid. He could hardly believe it. His son was moving also, kicking like a child in the midst of a dream.

He tried to get the children to speak and to stop shaking but could accomplish neither task.

Around them, others were waking in similar states.

“What’s wrong with everybody?” his wife asked.

“Caught between life and death,” Manu-hotep guessed. “Who can say what pain that brings?”

“What do we do?”

There was no thought of wavering now. No hesitation. “We do as Osiris commands,” he said. “We blind the Pharaoh.”

He got up and walked through the ash, rushing to the altar. The red amphora of poison was still there, though it was now black with soot. He grasped it, filled with belief and conviction. Filled with hope as well.

He and the others left the temple, waiting for their children to speak or to respond to them or even to hold still. It would be weeks before that happened, months before those who’d been revived would begin to function as they had before their time in death’s grip. But by then, the eyes of Akhenaten would be growing dim and the reign of the heretic Pharaoh would be rapidly drawing to a close.

Aboukir Bay, at the mouth of the Nile River August 1, 1798, shortly before dusk

The sound of cannon fire thundered across the wide expanse of Aboukir Bay as flashes lit up the distant gray twilight. Geysers of white water erupted as iron projectiles fell short of their targets, but the attacking squadron of ships was closing in fast on an anchored fleet. The next barrage would not be fired in vain.

Headed out toward this tangle of masts was a longboat, powered by the strong arms of six French sailors. It was making a direct line for the ship at the center of the battle in what seemed like a suicidal mission.

“We’re too late,” one of the rowers shouted.

“Keep pulling,” the only officer in the group replied. “We must reach L’Orient before the British surround her and engage the entire fleet.”

The fleet in question was Napoleon’s grand Mediterranean armada, seventeen ships, including thirteen ships of the line. They returned English volleys with a series of thunderclaps all their own and the entire scene became rapidly shrouded in gun smoke even before dusk fell.

In the center of the longboat, fearing for his life, was a French civilian named Emile D’Campion.

Had he not been expecting to die at any moment, D’Campion might have admired the raw beauty of the display. The artist in him—for he was a known painter—might have considered how best to craft such ferocity onto the stillness of a canvas. How to depict the flashes of silent light that lit up the battle. The terrifying whistle of the cannonballs screaming in toward their targets. The tall masts, huddled together like a thicket of trees awaiting the ax. He might have taken special care to contrast the cascades of white water with the last hint of pink and blue in the darkening sky. But D’Campion was shaking from head to toe, gripping the side of the boat to hold himself steady.

When a stray shot cratered the bay a hundred yards from where they were, he spoke. “Why in God’s name are they firing at us?”

“They’re not,” the officer replied.

“Then how do you explain the cannon shots hitting so close to us?”

“English marksmanship,” the officer said. “It is extrêmement pauvre. Very poor.”

The sailors laughed. A little too hard, D’Campion thought. They were also afraid. For months they’d known they were playing the fox to the British hounds. They’d missed each other at Malta by only a week and at Alexandria by no more than twenty-four hours. Now, after putting Napoleon’s army ashore and anchoring there at the mouth of the Nile, the English and their hunter of choice, Horatio Nelson, had finally caught the scent.

“I must have been born under a dark star,” D’Campion muttered to himself. “I say we turn back.”

The officer shook his head. “My orders are to deliver you and these trunks to Admiral Brueys aboard L’Orient.”

“I know your orders,” D’Campion replied, “I was there when Napoleon gave them to you. But if you intend to row this boat in between the guns of L’Orient and Nelson’s ships, you’ll only succeed in getting us all killed. We must turn back, either to shore or to one of the other ships.”

The officer turned from his men and gazed over his shoulder toward the center of battle. L’Orient was the largest, most powerful warship in the world. She was a fortress on the water, with a hundred and thirty cannon at her disposal, weighing five thousand tons and carrying over a thousand men. She was flanked by two other French ships of the line in what Admiral Brueys considered an unassailable defensive position. Except no one seemed to have informed the British of this, whose smaller ships were charging directly at her undaunted.

Broadsides were exchanged at close range between L’Orient and the British vessel Bellerophon. The smaller British vessel took the worst of it, as her starboard rail shattered to kindling and two of her three masts cracked and fell, smashing against her decks. Bellerophon drifted south, but even as she left the battle, other British ships charged into the gap. In the meantime, their smaller frigates swung around into the shallows and cut between the gaps in the French line.

D’Campion considered rowing into such a melee the equivalent of insanity and he made another suggestion. “Why not just deliver the trunks to Admiral Brueys once he’s dispatched the British fleet?”

At this, the officer nodded. “You see?” he said to his men. “This is why Le General calls him savant.”

The officer pointed to one of the ships in the French rear guard, which had yet to be engaged by the attacking British. “Make for the Guillaume Tell,” he said. “Rear Admiral Villeneuve is there. He’ll know what to do.”

The rowing resumed in earnest and the small boat turned away from the deadly battle with all due haste. Maneuvering through the darkness and the drifting smoke, the crew brought their boat toward the rear part of the French line where four ships waited, strangely quiet as the battle raged up ahead.

No sooner had the longboat bumped the thick timbers of the Guillaume Tell than ropes were lowered. They were rapidly secured and both men and cargo hauled aboard.

By the time D’Campion reached the deck, the ferocity and savagery of the battle had risen to a pitch he could scarcely have imagined. The British had achieved a huge tactical advantage despite being slightly outnumbered. Instead of taking on the entire French fleet broadside to broadside, they’d ignored the rear guard of French ships and doubled up their fire on the forward part of the French line. Each French vessel was now fighting two British ships, one on either side. The results were predictable: the glorious French armada was being battered to ruin.

“Admiral Villeneuve wishes to see you,” a staff officer told D’Campion.

He was ushered belowdecks and into the presence of Rear Admiral Pierre-Charles Villeneuve. The admiral had a full head of white hair, a narrow face marked by a high forehead and a long Roman nose. He wore an impeccable uniform, dark blue top, embroidered with gold and crossed with a red sash. To D’Campion he seemed more ready for a parade than a battle.

For a few moments Villeneuve toyed with the locks on the heavy trunk. “I understand you’re one of Napoleon’s savants.”

Savant was Bonaparte’s word, annoying to D’Campion and some of the others. They were scientists and scholars, brought together by General Napoleon and ushered to Egypt, where he insisted treasures would be found to satisfy both body and soul.

D’Campion was a budding expert in the new discipline of translating ancient languages and no place offered a greater mystery or potential in that regard than the Land of the Pyramids and the Sphinx.

And D’Campion was not just one of the savants. Napoleon had chosen him personally to seek the truth behind a mysterious legend. A great reward was promised, including wealth greater than D’Campion could earn in ten lifetimes and lands that would be given him by the new Republic. He would receive medals and glory and honor, but first he must find something rumored to exist in the Land of the Pharaohs—a way to die and then return to life once again.

For a month D’Campion and his little detachment had been removing all that they could carry from a place the Egyptians called the City of the Dead. They took papyrus writings, stone tablets and carvings of every kind. What they couldn’t move they copied.

“I’m part of the Commission of Science and Art,” D’Campion said, using the official name he preferred.

Villeneuve seemed unimpressed. “And what have you brought aboard my ship, Commissioner?”

D’Campion steeled himself. “I cannot say, Admiral. The trunks are to remain closed on the orders of General Napoleon himself. Their contents are not to be discussed.”

Villeneuve still seemed unimpressed. “They can always be sealed again. Now, hand me your key.”

“Admiral,” D’Campion warned, “the General will not be pleased.”

“The General is not here!” Villeneuve snapped.

Napoleon was already a powerful figure at this time, but he was not yet emperor. The Directory, made up of five men who’d led the Revolution, remained in charge while others jockeyed for power.

Still, D’Campion found it hard to comprehend Villeneuve’s actions. Napoleon was not a man to be trifled with, nor was Admiral Brueys, who was Villeneuve’s direct superior and currently fighting for his life less than a half mile away. Why was Villeneuve bothering with such matters when he should be engaging Nelson?

“The key!” Villeneuve demanded.

D’Campion snapped out of his hesitation and made the prudent decision. He pulled the key from around his neck and handed it over. “I commit the trunks to your care, Admiral.”

“As well you should,” Villeneuve said. “You may leave me.”

D’Campion turned but stopped in his tracks and risked another question. “Are we to join the battle soon?”

The admiral raised an eyebrow as if the question were absurd. “We have no orders to do so.”

“Orders?”

“There have been no signals from Admiral Brueys on L’Orient.”

“Admiral,” D’Campion said, “the English are pounding him from both sides. Surely this is no time to wait for an order.”

Villeneuve stood suddenly and pushed toward D’Campion like a charging bull. “You dare instruct me?!”

“No, Admiral, it’s just—”

“The wind is contrary,” Villeneuve snapped, waving a dismissive hand. “We would have to tack all over the bay to have any hope of joining the fracas. Easier for Admiral Brueys to drift back to our position and allow us to support him. But, as yet, he chooses not to do so.”

“Surely we can’t just sit here?”

Villeneuve snatched a dagger from the top of his desk. “I will kill you where you stand if you speak to me this way again. What do you know about sailing or fighting anyway, Savant?”

D’Campion knew he’d overstepped his bounds. “My apologies, Admiral. It’s been a difficult day.”

“Leave me,” Villeneuve said. “And be thankful we don’t sail into battle yet for I would put you out on the foredeck with a bell around your shoulders for the British to aim at.”

D’Campion stepped back, bowed slightly and left the admiral’s sight as quickly as possible. He went topside, found an empty space along the bow of the ship and watched the carnage in the distance.

Even from a distance he found the ferocity almost staggering to behold. For a period of several hours the two fleets blasted at each other from point-blank range; side-by-side, mast-to-mast, sharpshooters abovedecks trying to kill anyone caught out in the open.

“Ce courage,” D’Campion mused. Such bravery.

But bravery would not be enough. By now, each British ship was firing three or four times for every shot loosed by the French. And, thanks to Villeneuve’s reluctance, they had more ships engaged in the battle.

In the center of the action, three of Nelson’s ships were pounding L’Orient, bludgeoning her into an unrecognizable hulk. Her beautiful lines and towering masts were long gone. Her thick oak sides were splintered and broken. Even as the few remaining cannon sounded, D’Campion could tell she was dying.

D’Campion noticed fires running like quicksilver along her main deck. The wicked flames darted here and there, showing no mercy, as they climbed across the fallen sails and dove down through open hatches and into her hold.

A sudden flash lit out, blinding D’Campion even as he shut his eyes against it. A crack of thunder followed louder than anything D’Campion had ever heard. He was thrown backward by a shock wave that singed his face and burned his hair.

He landed on his side, gasping for air, rolled over several times and tamped out flames on his coat. When he finally looked up, he was shocked.

L’Orient was gone.

Fire burned on the water in a wide circle around the wreckage. So massive was the blast that six other ships were burning, three from the English fleet and three from the French. The din of battle halted as crewmen with pumps and buckets tried desperately to prevent their own fiery destruction.

“The fire must have reached her magazine,” the voice of a saddened French sailor whispered.

Deep in the hold of each warship were hundreds of barrels of gunpowder. The slightest spark was dangerous.

Tears stained the sailor’s face as he spoke, and though D’Campion was sick to his stomach, he was too exhausted for any real emotion to surface.

More than a thousand men had been on L’Orient when it arrived at Aboukir. D’Campion had traveled aboard it himself, dining with Admiral Brueys. Almost every man he’d come to know on this journey had been on that ship, even the children, sons of the officers as young as eleven. Staring at the devastation, D’Campion could not imagine a single one of them had survived.

Gone too—aside from the trunks Villeneuve had now taken possession of—were the efforts of his month in Egypt and the opportunity of a lifetime.

D’Campion slumped to the deck. “The Egyptians warned me,” he said.

“Warned you?” the sailor repeated.

“Against taking stones from the City of the Dead. A curse would follow, they insisted. A curse . . . I laughed at them and their foolish superstitions. But now . . .”

He tried to stand but collapsed to the deck. The sailor came to his aid and helped him to get belowdecks. There, he waited for the inevitable English onslaught to finish them.

It arrived at dawn, as the British regrouped and moved to attack what remained of the French fleet. But instead of man-made thunder and the sickening crack of timbers rendered by iron cannonballs, D’Campion heard only the wind as the Guillaume Tell began to move.

He went up on deck to find they were traveling northeast under full sail. The British were following but rapidly falling behind. Occasional puffs of smoke marked their futile efforts to hit the Guillaume Tell from so far off. And soon even their sails were nearly invisible on the horizon.

For the rest of his days, Emile D’Campion would question Villeneuve’s courage, but he would never malign the man’s cunning and would insist to any who listened that he owed his life to it.

By midmorning the Guillaume Tell and three other ships under Villeneuve’s command had left Nelson and his merciless Band of Brothers far behind. They made their way to Malta, where D’Campion would spend the remainder of his life, working, studying and even conversing by letter with Napoleon and Villeneuve, all the time wondering about the lost treasures he’d taken from Egypt.

M.V. Torino, seventy miles west of MaltaPresent day

The M.V. Torino was a three-hundred-foot steel-hulled freighter built in 1973. With her advancing age, small size and slow speed, she was nothing more than a “coaster” now, traveling short routes across the Mediterranean, hitting various small islands, on a circuit that took in Libya, Sicily, Malta and Greece.

In the hour before dawn, she was sailing west, seventy miles from her last port of call in Malta and heading for the small Italian-controlled island of Lampedusa.

Despite the early hour, several men crowded the bridge. Each of them nervous—and with good reason. For the past hour an unmarked vessel running without lights had been shadowing them.

“Are they still closing in on us?”

The question came as a shout from the ship’s master, Constantine Bracko, a stocky man with pile-driver arms, salt-and-pepper hair and stubble on his face like coarse sandpaper.

With his hand on the wheel, he waited for an answer. “Well?”

“The ship is still there,” the first mate shouted. “Matching our turn. And still gaining.”

“Shut off all our lights,” Bracko ordered. Another crewman closed a series of master switches and the Torino went dark. With the ship blacked out, Bracko changed course yet again.

“This won’t do us much good if they have radar or night vision goggles,” the first mate said.

“It’ll buy us some time,” Bracko replied.

“Maybe it’s the customs service?” another crewman asked. “Or the Italian Coast Guard?”

Bracko shook his head. “We should be so lucky.”

The first mate knew what that meant. “Mafia?”

Bracko nodded. “We should have paid. We’re smuggling in their waters. They want their cut.”

Thinking he could slip by in the dark of night, Bracko had taken a chance. His roll of the dice had come out badly. “Break out the weapons,” he said. “We have to fight.”

“But Constantine,” the first mate said. “That will go badly with what we’re carrying.”

The Torino’s deck was loaded with shipping containers, but hidden in most of them were pressurized tanks as large as city buses filled with liquefied propane. They were smuggling other things as well, including twenty barrels of some mysterious substance brought on board by a cust. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...