- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

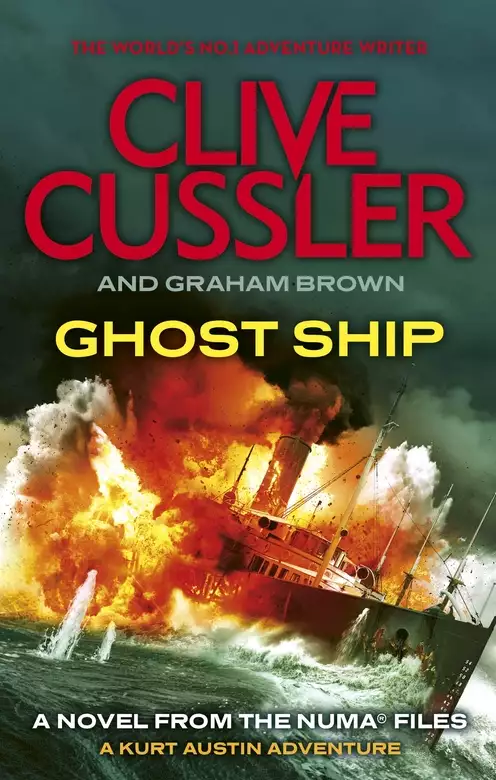

The dazzling new novel in the #1 New York Times -bestselling series from Clive Cussler, the grand master of adventure. When Kurt Austin is injured attempting to rescue the passengers and crew from a sinking yacht, he wakes with fragmented and conflicted memories. Did he see an old friend and her children drown, or was the yacht abandoned when he came aboard? For reasons he cannot explain, Kurt doesn' t trust either version of his recollection. Determined to know the truth, he begins to search for answers, and soon finds himself descending into a shadowy world of state-sponsored cybercrime, and uncovering a pattern of vanishing scientists, suspicious accidents, and a web of human trafficking. With the help of Joe Zavala, he takes on the sinister organization at the heart of this web, facing off with them in locations ranging from Monaco to North Korea to the rugged coasts of Madagascar. But where he will ultimately end up even he could not begin to guess.

Release date: May 27, 2014

Publisher: G.P. Putnam's Sons

Print pages: 448

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Ghost Ship

Clive Cussler

Durban, South Africa, July 25, 1909

They were driving into a void, or so it seemed to Chief Inspector Robert Swan of the Durban Police Department.

On a moonless night, beneath a sky as dark as India ink, Swan rode shotgun in the cab of a motortruck as it rumbled down a dusty track in the countryside north of Durban. The headlights of the big Packard cast yellow beams of light that flickered and bounced and did little to brighten the path ahead. As he stared into the gloom, Swan could see no more than forty yards of the rutted path at any one time.

“How far to this farmhouse?” he asked, turning toward a thin, wiry man named Morris, who was wedged in next to the driver.

Morris checked his watch, leaned toward the driver, and checked the odometer of the truck. After some mental calculations, he glanced down at the map he held. “We should be there soon, Inspector. No more than ten minutes to go, I’d say.”

The chief inspector nodded and grabbed the doorsill as the bumpy ride continued. The Packard was known as a Three Ton, the latest from America and one of the first motor vehicles to be owned by the Durban Police Department. It had come off the boat with the customized cab and windshield. Enterprising workmen from the newly formed motor pool had built a frame to cover the flat bed and stretched canvas over it, though no one had done anything to make it more comfortable.

As the truck bounced and lurched over the rutted buggy trail, Swan decided he would rather be on horseback. But what the big rig lost in comfort it made up for in hauling power. In addition to Swan, Morris, and the driver, eight constables rode in back.

Swan leaned on the doorsill and turned to look behind him. Four sets of headlights followed. Three cars and another Packard. All told, Swan had nearly a quarter of the Durban police force riding with him.

“Are you sure we need all these men?” Morris asked.

Perhaps it was a bit much, Swan thought. Then again, the criminals they were after—a group known in the papers as the Klaar River Gang—had numbers of their own. Rumors put them between thirty and forty, depending on whom one believed.

Though they’d begun as common highwaymen, robbing others and extorting those who tried to make an honest living doing business out in the Veld, they’d grown more cunning and violent in the last six months. Farmhouses of those who refused to pay protection money were being burned to the ground. Miners and travelers were disappearing without a trace. The truth came to light when several of the gang were captured trying to rob a bank. They were brought back to Durban for interrogation only to be rescued in a brazen attack that left three policemen dead and four others wounded.

It was a line that Swan would not allow them to cross. “I’m not interested in a fair fight,” he explained. “Need I remind you what happened two days ago?”

Morris shook his head, and Swan rapped his hand on the partition that separated the cab from the back of the truck. A panel slid open and the face of a burly man appeared, all but filling the window.

“Are the men ready?” Swan asked.

“We’re ready, Inspector.”

“Good,” Swan said. “Remember, no prisoners tonight.”

The man nodded his understanding, but the words caused Morris to offer a sideways glance.

“You have a problem?” Swan barked.

“No, sir,” Morris said, looking back at his map. “It’s just that . . . we’re almost there. Just over this hill.”

Swan turned his attention forward once again and took a deep breath, readying himself. Almost immediately he caught the scent of smoke. It was distinct in flavor, like a bonfire.

The Packard crested the hill moments later, and the coal-black night was cleaved in two by a frenzied orange blaze on the field down below them. The farmhouse was burning from one side to the other, whirls of fire curling around it and reaching toward the heavens.

“Bloody hell,” Swan cursed.

The vehicles raced down the hill and spread out. The men poured forth and took up positions surrounding the house.

No one hit them. No one fired.

Morris led a squad closer. They approached from upwind and darted into the last section of the barn that wasn’t ablaze. Several horses were rescued, but the only gang members they found were already dead. Some of them half burned, others merely shot and left to die.

There was no hope of fighting the fire. The ancient wood and the oil-based paint crackled and burned like petrol. It put out such heat that Swan’s men were soon forced to back off or be broiled alive.

“What happened?” Swan demanded of his lieutenant.

“Looks like they had it out among themselves,” Morris said.

Swan considered that. Before the arrests in Durban, rumors had been swirling that suggested the gang was fraying at the seams. “How many dead?”

“We’ve found five. Some of the boys think they saw two more inside, but they couldn’t reach ’em.”

At that moment gunfire rang out.

Swan and Morris dove behind the Packard for cover. From sheltered positions, some of the officers began to shoot back, losing stray rounds into the inferno.

The shooting continued, oddly timed and staccato, though Swan saw no sign of bullets hitting nearby.

“Hold your fire!” he shouted. “But keep your heads down.”

“But they’re shooting at us,” one of the men shouted.

Swan shook his head even as the pop-pop of the gunfire continued. “It’s just ammunition going off in the blaze.”

The order was passed around, shouted from one man to the next. Despite his own directive, Swan stood up, peering over the hood of the truck.

By now the inferno had enveloped the entire farmhouse. The remaining beams looked like the bones of a giant resting on some Nordic funeral pyre. The flames curled around and through them, burning with a strange intensity, bright white and orange with occasional flashes of green and blue. It looked like hell itself had risen up and consumed the gang and their hideout from within.

As Swan watched, a massive explosion went off deep inside the structure, blowing the place into a fiery scrap. Swan was thrown back by the force of the blast, landing hard on his back, as chunks of debris rattled against the sides of the Packard.

Moments after the explosion, burning confetti began falling, as little scraps of paper fluttered down by the thousands, leaving trails of smoke and ash against the black sky. As the fragments kissed the ground, they began to set fires in the dry grass.

Seeing this, Swan’s men went into action without delay, tamping out the embers to prevent a brushfire from surrounding them.

Swan noticed several fragments landing nearby. He rolled over and stretched for one of them, patting it out with his hand. To his surprise, he saw numbers, letters, and the stern face of King George staring back at him.

“Tenners,” Morris said excitedly. “Ten-pound notes. Thousands of them.”

As the realization spread through the men, they redoubled their efforts, running around and gathering up the charred scraps with a giddy enthusiasm they rarely showed for collecting evidence. Some of the notes were bundled and not too badly burned. Others were like leaves in the fireplace, curled and blackened beyond recognition.

“Gives a whole new meaning to the term blowing the loot,” Morris said.

Swan chuckled, but he wasn’t really listening, his thoughts were elsewhere; studying the fire, counting the bodies, working the case as an inspector’s mind should.

Something was not right, not right at all.

At first, he put it down to the anticlimactic nature of the evening. The gang he’d come to make war on had done the job for him. That he could buy. He’d seen it before. Criminals often fought over the spoils of their crimes, especially when they were loosely affiliated and all but leaderless, as this gang was rumored to be.

No, Swan thought, this was suspicious on a deeper level.

Morris seemed to notice. “What’s wrong?”

“It makes no sense,” Swan replied.

“What part of it?”

“The whole thing,” Swan said. “The risky daylight bank job. The raid to get their men out. The gunfight in the street.”

Morris stared at him blankly. “I don’t follow you.”

“Look around,” Swan suggested. “Judging by the storm of burnt cash raining down on us, these thugs were sitting on a small fortune.”

“Yes,” Morris agreed. “So what?”

“So why rob a heavily defended bank in broad daylight if you’re already loaded to the gills with cash? Why risk shooting up Durban to get your mates out only to gun them down back here?”

Morris stared at Swan for a long moment before nodding his agreement. “I have no idea,” he said. “But you’re right. It makes no sense at all.”

The fire continued to burn well into the morning hours, only dying when the farmhouse was consumed. The operation ended without casualties among the police, and the Klaar River Gang was never heard from again.

Most considered it a stroke of good fortune, but Swan was never convinced. He and Morris would discuss the events of that evening for years, well into their retirement. Despite many theories and guesses as to what really went on, it was a question they would never be able to answer.

170 miles West-Southwest of Durban, July 27, 1909

The SS Waratah plowed through the waves on a voyage from Durban to Cape Town, rolling noticeably with the growing swells. Dark smoke from coal-fired boilers spilled from her single funnel and was driven in the opposite direction by a contrary wind.

Sitting alone in the main lounge of the five-hundred-foot steamship, fifty-one-year-old Gavin Brèvard felt the vessel roll ponderously to starboard. He watched the cup and saucer in front of him slide toward the edge of the table, slowly at first, and then picking up speed as the angle of the ship’s roll increased. At the last second, he grabbed for the cup, preventing it from sliding off the edge and clattering to the floor.

The Waratah remained at a sharp pitch, taking a full two minutes to right herself, and Brèvard began to worry about the vessel he’d booked passage on.

In a prior life, he’d spent ten years at sea aboard various steamers. On those ships the recoil was quicker, the keel more adept at righting itself. This ship felt top-heavy to him. It made him wonder if something was wrong.

“More tea, sir?”

Deep in thought, Brèvard barely noticed the waiter in the uniform of the Blue Anchor Line.

He held out the cup he’d saved from destruction. “Merci.”

The waiter topped it off and moved on. As he left, a new figure came into the room, a broad-shouldered man of perhaps thirty, with reddish hair and a ruddy face. He made a direct line for Brèvard, taking a seat in the chair opposite.

“Johannes,” Brèvard said in greeting. “Glad to see you’re not trapped in your cabin like the others.”

Johannes looked a little green, but he seemed to be holding up. “Why have you called me here?”

Brèvard took a sip of the tea. “I’ve been thinking. And I’ve decided something important.”

“And what might that be?”

“We’re far from safe.”

Johannes sighed and looked away. Brèvard understood. Johannes thought him to be a worrier. A fear-laden man. But Brèvard was just trying to be cautious. He’d spent years with people chasing him, years living under the threat of imprisonment or death. He had to think five steps ahead just to remain alive. It had tuned his mind to a hyperattentive state.

“Of course we’re safe,” Johannes replied. “We’ve assumed new identities. We left no trail. The others are all dead, and the barn has been burned to the ground. Only our family continues on.”

Brèvard took another sip of tea. “What if we’ve missed something?”

“It doesn’t matter,” Johannes insisted. “We’re beyond the reach of the authorities here. This ship has no radio. We might as well be on an island somewhere.”

That was true. As long as the ship was at sea, they could rest and relax. But the journey would end soon enough.

“We’re only safe until we dock in Cape Town,” Brèvard pointed out. “If we haven’t covered our trail as perfectly as we think, we may arrive to a greeting of angry policemen or His Majesty’s troops.”

Johannes did not reply right away. He was thinking, soaking the information in. “What do you suggest?” he asked finally.

“We have to make this journey last forever.”

“And how do we do that?”

Brèvard was speaking metaphorically. He knew he had to be more concrete for Johannes. “How many guns do we have?”

“Four pistols and three rifles.”

“What about the explosives?”

“Two of the cases are still full,” Johannes said with a scowl. “Though I’m not sure it was wise to bring them aboard.”

“They’ll be fine,” Brèvard insisted. “Wake the others, I have a plan. It’s time we took destiny into our own hands.”

—

CAPTAIN JOSHUA ILBERY stood on the Waratah’s bridge despite it being time for the third watch to take over. The weather concerned him. The wind was gusting to fifty knots, and it was blowing opposite to the tide and the current. This odd combination was building the waves into sharp pyramids, unusually high and steep, like piles of sand pushed together from both directions.

“Steady on, now,” Ilbery said to the helmsman. “Adjust as needed, we don’t want to be broadsided.”

“Aye,” the helmsman said.

Ilbery lifted the binoculars. The light was fading as evening came on, and he hoped the wind would subside in the night.

Scanning the whitecaps ahead of him, Ilbery heard the bridge door open. To his surprise, a shot rang out. He dropped the binoculars and spun to see the helmsman slumping to the deck, clutching his stomach. Beyond him stood a group of passengers with weapons, one of whom walked over and took the helm.

Before Ilbery could utter a word or grab for a weapon, a ruddy-faced passenger slammed the butt of an Enfield rifle into his gut. He doubled over and fell back, landing against the bulkhead.

The man who’d attacked him aimed the barrel of the Enfield at his heart. Ilbery noticed it was held by rough hands, more fitting on a farmer or rancher than a first-class passenger. He looked into the man’s eyes and saw no mercy. He couldn’t be sure of course, but Ilbery had little doubt the man he was facing had shot and killed before.

“What is the meaning of this?” Ilbery growled.

One of the group stepped toward him. He was older than the others, with graying hair at the temples. He wore a finer suit and carried himself with the loose elegance of a leader. Ilbery recognized him as one of a group who’d come on board in Durban. Brèvard, was the name. Gavin Brèvard.

“I demand an explanation,” Ilbery said.

Brèvard smirked at him. “I should have thought it quite obvious. We’re commandeering this ship. You’re going to set a new course away from the coast and then back to the east. We’re not going to Cape Town.”

“You can’t be serious,” Ilbery said. “We’re in the middle of a bad stretch. The ship is barely responding as it is. To make a turn now would—”

Gavin aimed the pistol at a spot halfway between the captain’s eyes. “I’ve worked on steamers before, Captain. Enough to know that this ship is top-heavy and performing poorly. But she’s not going to go over, so stop lying to me.”

“This ship will surely go to the bottom,” Ilbery said.

“Give the order,” Brèvard demanded, “or I’ll blow a hole in your skull and pilot this ship myself.”

Ilbery’s eyes narrowed to slits. “Perhaps you can navigate, but what about the rest of the duties? Do you and this lot intend to man the ship yourselves?”

Brèvard smiled wryly. He’d known from the start that this was his weakness, the chink in his armor. He had eight others with him, three of them children. Even if they’d been adults, nine people couldn’t even keep the fires stoked for long, let alone guard the passengers and crew, and pilot the ship at the same time.

But Brèvard was used to playing the angles. His whole life was a study in getting others to do as he wished, either against their wills or without them knowing they were doing his bidding. He’d known he needed leverage, and the explosives in the two cases enabled him to turn the odds in his favor.

“Bring in the prisoner,” he said.

Ilbery watched as the bridge door was opened and an unkempt teenager appeared. This one brought in a man covered in coal dust. Blood flowed from a broken nose and a gash across his forehead.

“Chief?”

“I’m sorry, Cap’n,” the chief said. “They tricked us. They used children to distract us. And then they overpowered us. Three of the lads are shot. But it’s so loud down there no one heard until it was too late.”

“What have they done?” the captain asked, his eyes growing wide.

“Dynamite,” the chief said. “A dozen sticks attached to boilers three and four.”

Ilbery turned to Brèvard. “Are you insane? You can’t put explosives in an environment like that. The heat, the embers. One spark and—”

“And we’ll all be blown to kingdom come,” Brèvard said, finishing the thought for him. “Yes, I’m well aware of the consequences. The thing is, a rope waits for me onshore, the kind that stretches one’s neck. If I’m going to die, I’d rather it be quick and glorious than slow and painful. So don’t test me. I have three of my people down there with rifles like these to make sure no one removes those explosives, at least not until I leave this ship at a port of my choosing. Now, do as I say and turn this vessel away from the coast.”

“And then what?” Ilbery asked.

“When we’ve reached our destination, we’ll take a few of your boats, a heap of supplies, and everyone’s cash and jewelry, and we’ll leave your ship and disappear. You and your crew will be free to sail back to Cape Town with a fantastic story to tell the world.”

Using the bulkhead behind him for support, Captain Ilbery forced himself up and stood. He stared at Brèvard with contempt. The man had him and both knew it.

“Chief,” he said without taking his eyes off the hijacker. “Take the helm and turn us about.”

The chief staggered to the wheel and pushed the hijacker aside and did as ordered. The rudder answered the helm, and the SS Waratah began to turn.

“Good decision,” Brèvard said.

Ilbery wondered about that, but knew he had no choice.

For his part, Brèvard was pleased. He sat down in a chair, laid the rifle across his lap, and studied the captain closely. Having spent his lifetime misleading others, from policemen to powder-wigged judges, Brèvard had learned that some men were easier to read than others. The honest ones were more obvious than the rest.

As Brèvard stared at this captain, he pegged him as one of those. A man with pride and smarts and a great sense of duty for his passengers and crew. That sense of duty compelled him to comply with Brèvard’s demands in order to protect the lives of those on board. But it also made him dangerous.

Even as he acquiesced, Ilbery stood tall and ramrod straight. Though he clutched his stomach from the blow he’d taken, he kept a fire burning in his eyes that beaten men didn’t have. All of which suggested the captain was not ready to relinquish his ship just yet. A countermove would come, sooner rather than later.

Brèvard didn’t blame the captain. Quite frankly, he respected him. All the same, he made a mental note to be ready.

SS Harlow—10 miles ahead of the Waratah

Like the captain of the Waratah, the captain of the Harlow was on the bridge. Thirty-foot waves and fifty-knot winds required it. He and his crew were making constant corrections, working hard to keep the Harlow from going off course. They’d even pumped in some extra water as ballast to help reduce the roll.

As the first officer reentered the bridge following an inspection run, the captain looked his way. “How are we faring, number one?”

“Shipshape from stem to stern, sir.”

“Excellent,” the captain said. He stepped to the bridge wing and glanced out behind them. The lights of another vessel could be seen on the horizon. She was several miles astern, and making a great deal of smoke.

“What do you make of her?” the captain asked. “She’s changed course, out away from the coast.”

“Could be a turn to get more clearance from the shoals,” the first officer said. “Or perhaps the wind and current are forcing her off. Any idea who it is?”

“Not sure,” the captain said. “She might be the Waratah.”

Moments later, a pair of flashes only seconds apart lit out from the vessel’s approximate position. They were bright white and then orange, but at this range there was no sound, like watching distant fireworks. When they faded, the horizon was dark.

Both the captain and first officer blinked and stared into that darkness.

“What was that?” the first officer asked. “An explosion?”

The captain wasn’t sure. He grabbed for the binoculars and took a moment to train them on the spot. There was no sign of fire, but a cold chill gripped his spine as he realized the lights of the mystery ship had vanished as well.

“Could have been flares from a brushfire on the shore behind them,” the first officer suggested. “Or heat lightning.”

The captain didn’t respond and continued to stare through the binoculars, sweeping the field of view. He hoped the first officer was right, but if the flashes of light had come from the shore or the sky, then what had happened to the ship’s lights visible only moments before?

—

UPON DOCKING, both men would learn that the Waratah was overdue and missing. She’d never made port in Cape Town, nor had she returned to Durban or made landfall anywhere else.

In quick succession both the Royal Navy and the Blue Anchor Line would dispatch ships in search of the Waratah, but they would return empty-handed. No lifeboats were found. No wreckage. No debris. No bodies floating in the water.

Over the years, nautical groups, government organizations, and treasure seekers would search for the wreck of the missing ship. They would use sonar, magnetometers, and satellite imaging. They would dispatch divers and submarines and ROVs to scour various wrecks along the coast. But it was all in vain. More than a century after her disappearance, not a single trace of the Waratah had ever been found.

Maputo Bay, Mozambique, September 1987

The sun was falling toward the horizon as an aging fifty-foot trawler sailed into the bay from the open waters of the Mozambique Channel. For Cuoto Zumbana, it had been a good day. The hold of his boat was filled with fresh fish, no nets had been torn or lost, and the old motor had survived yet another journey—though it continued to belch gray smoke.

Satisfied with life, Zumbana closed his eyes and turned toward the sun, letting it bathe the weathered folds of his face. There was little he enjoyed more than that glorious feeling. Such peace it brought him that the excited shouts of his crew did not break him from it at first.

“Mashua,” one shouted.

Zumbana opened his eyes, squinting in the glare as the sunlight blazed off the sea like liquid fire. Blocking the light with his hand, he saw what the men were pointing at, a small wooden dinghy bobbing in the chop of the late afternoon. It seemed to be adrift, and there didn’t appear to be anyone on board.

“Take us to it,” he ordered. To find a small boat he could sell would only make the day better. He would even share some of the money with the crew.

The trawler changed course, and the old engine chugged a little harder. Soon, they were closing the gap.

Zumbana’s face wrinkled. The small boat was badly weathered and looked hastily patched. Even from fifty feet away he could see that much of it was rotted.

“Someone must have dumped it just to be rid of it,” one of his crewmen said.

“There might be something of value on board,” Zumbana said. “Take us alongside.”

The helmsman did as ordered, and the trawler eased to a stop beside the dilapidated craft. As they bumped it, another crewman hopped aboard. Zumbana threw him a rope, and the two boats were quickly tied off and drifting together.

From his position, Zumbana saw empty cooking pots and piles of rags, certainly nothing of value, but as the crewman pulled a moth-eaten blanket aside all thoughts of money were chased from his mind.

A young woman and two boys lay beneath the old blanket. They were clearly dead. Their faces were covered with sores from the sun and their bodies stiff. Their clothing was tattered, and a bloodstained rag was tied to the woman’s shoulder. A closer look revealed scabbed wrists and ankles as if the three of them had once been held in cuffs and restraints.

Zumbana crossed himself.

“We should leave it,” one of the crewmen said.

“It’s a bad omen,” another added.

“No. We must respect the dead,” Zumbana replied. “Especially those who have been taken so young.”

The men looked at him suspiciously but did as they were ordered. With a rope secured for towing, they turned once again for shore with the old double-ended boat trailing out behind them.

Zumbana moved to the stern, where he could keep an eye on the small craft. His gaze went from the boat to the horizon beyond. He wondered about the occupants of the small boat. Who were they? Where had they come from? What danger had they escaped only to die on the open sea? So young, he thought, considering the three bodies. So fragile.

The boat itself was another mystery. The top plank in the boat’s side seemed as if it might have once been painted with a name, but it was unreadable now. He worried if the boat would make it into port. Unlike its dead passengers, it seemed ancient. Certainly it was older than the three occupants. In fact, it looked to him like it might belong to another era all together.

Indian Ocean, March 2014

A flash of blue lightning forked across the horizon. For a second or two it lit up the gray darkness where sea and storm met.

Kurt Austin stared into that darkness from the rear section of a Sikorsky Jayhawk as the big helicopter shouldered its way through bands of pouring rain. Turbulence shook the craft, and thirty-foot swells rolled beneath them, their tops blown off by the howling wind.

As the lightning faded, Kurt saw his reflection on the glass. Roughly forty, with silver-gray hair, Kurt was handsome in the right kind of light. A strong jawline and piercing blue eyes saw to that. But like a truck that spent its days on the worksite instead of in the garage, his face carried the miles in plain view.

The lines around his eyes were etched a little deeper than most. A collection of faded scars from fistfights, car crashes, and other incidents marked his brow and jaw. It was the face of a man who seemed ready for anything, determined and unyielding, even as the helicopter neared the limits of its range.

He pressed the intercom switch and looked ahead to where his friend Joe Zavala sat in the copilot’s seat. “Anything?”

“Nothing,” Joe called back.

Kurt and Joe worked for NUMA, the National Underwater Marine Agency, a branch of the American government dedicated to the study and preservation of the sea. But, at

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...