- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

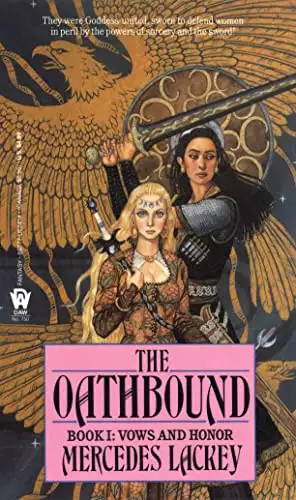

The first book in the Vows and Honor trilogy unites swordmaster and sorceress in a quest for revenge in this thrilling epic fantasy.

She was Tarma. Born to the Clan of the Hawk of the nomadic Shin'a'in people, she saw her entire clan slain by brigands. Vowing blood revenge upon the murderers, she became one of the sword-sworn, the most elite of all warriors. And trained in all the forms of death-dealing combat, she took to the road in search of her enemies.

She was Kethry. Born to a noble house, sold into a hateful "marriage," she fled life's harshness for the sanctuary of the White Winds, a powerful school of sorcery. Becoming an adept, she pledged to use her talents for the greatest good. Yet unlike other sorcerers, Kethry could use worldly weapons as well as magical skills. And when she became the bearer of a uniquely magical sword that drew her to those in need, Kethry was led to a fateful meeting with Tarma.

United by sword-spell and the will of the Goddess, Tarma and Kethry swore a blood oath to carry on their mutual fight against evil. And together, swordsmaster and sorceress set forth to fulfill their destiny . . .

Release date: July 5, 1988

Publisher: DAW

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Oathbound

Mercedes Lackey

NOVELS BY MERCEDES LACKEY

available from DAW Books:

THE HERALDS OF VALDEMAR

ARROWS OF THE QUEEN

ARROW’S FLIGHT

ARROW’S FALL

THE LAST HERALD-MAGE

MAGIC’S PAWN

MAGIC’S PROMISE

MAGIC’S PRICE

THE MAGE WINDS

WINDS OF FATE

WINDS OF CHANGE

WINDS OF FURY

THE MAGE STORMS

STORM WARNING

STORM RISING

STORM BREAKING

VOWS AND HONOR

THE OATHBOUND

OATHBREAKERS

OATHBLOOD

THE COLLEGIUM CHRONICLES

FOUNDATION

INTRIGUES

CHANGES

REDOUBT

BASTION

BY THE SWORD

BRIGHTLY BURNING

TAKE A THIEF

EXILE’S HONOR

EXILE’S VALOR

VALDEMAR ANTHOLOGIES:

SWORD OF ICE

SUN IN GLORY

CROSSROADS

MOVING TARGETS

CHANGING THE WORLD

FINDING THE WAY

UNDER THE VALE

Written with LARRY DIXON:

THE MAGE WARS

THE BLACK GRYPHON

THE WHITE GRYPHON

THE SILVER GRYPHON

DARIAN’S TALE

OWLFLIGHT

OWLSIGHT

OWLKNIGHT

OTHER NOVELS

GWENHWYFAR

THE BLACK SWAN

THE DRAGON JOUSTERS

JOUST

ALTA

SANCTUARY

AERIE

THE ELEMENTAL MASTERS

THE SERPENT’S SHADOW

THE GATES OF SLEEP PHOENIX AND ASHES

THE WIZARD OF LONDON

RESERVED FOR THE CAT

UNNATURAL ISSUE

HOME FROM THE SEA

STEADFAST

BLOOD RED

Anthologies:

ELEMENTAL MAGIC

ELEMENTARY

And don’t miss:

THE VALDEMAR COMPANION

Edited by John Helfers and Denise Little

Dedicated to

Lisa Waters

for wanting to see it

and my parents

for agreeing with her

Introduction

This is the tale of an unlikely partnership: that of the Shin’a’in swordswoman and celibate Kal’enedral, Tarma shena Tale’sedrin and the nobly-born sorceress Kethry, member of the White Winds school, whose devotees were sworn to wander the world using their talents for the greatest good. How these two met is told in the tale “Sword Sworn,” published in Marion Zimmer Bradley’s anthology SWORD AND SORCERESS III. A second of the accounts of their wandering life will be seen in the fourth volume of that series. But this story begins where that first tale left off, when they have recovered from their ordeal and are making their way back to the Dhorisha Plains and Tarma’s home.

One

The sky was overcast, a solid gray sheet that seemed to hang just barely above the treetops, with no sign of a break in the clouds anywhere. The sun was no more than a dimly glowing spot near the western horizon, framed by a lattice of bare black branches. Snow lay at least half a foot thick everywhere in the forest, muffling sound. A bird flying high on the winter wind took dim notice that the forest below him extended nearly as far as he could see no matter which way he looked, but was neatly bisected by the Trade Road immediately below him. Had he flown a little higher (for the clouds were not as low as they looked), he might have seen the rooftops and smokes of a city at the southern end of the road, hard against the forest. Although the Trade Road had seen enough travelers of late that the snow covering it was packed hard, there were only two on it now. They had stopped in the clearing halfway through the forest that normally saw heavy use as an overnighting point. One was setting up camp under the shelter of a half-cave of rock and tree trunks piled together—partially the work of man, partially of nature. The other was a short distance away, in a growth-free pocket just off the main area, picketing their beasts.

The bird circled for a moment, swooping lower, eyeing the pair with dim speculation. Humans sometimes meant food—

But there was no food in sight, at least not that the bird recognized as such. And as he came lower still, the one with the beasts looked up at him suddenly, and reached for something slung at her saddlebow.

The bird had been the target of arrows often enough to recognize a bow when he saw one. With a squawk of dismay, he veered off, flapping his wings with all his might, and tracing a twisty, convoluted course out of range. He wanted to be the eater, not the eaten!

• • •

Tarma sighed as the bird sped out of range, unstrung her bow, and stowed it back in the saddle-quiver. She hunched her shoulder a little beneath her heavy wool coat to keep her sword from shifting on her back, and went back to her task of scraping the snow away from the grass buried beneath it with gloved hands. Somewhere off in the far distance she could hear a pair of ravens calling to each other, but otherwise the only sounds were the sough of wind in branches and the blowing of her horse and Kethry’s mule. The Shin’a’in place of eternal punishment was purported to be cold; now she had an idea why.

She tried to ignore the ice-edged wind that seemed to cut right through the worn places in her nondescript brown clothing. This was no place for a Shin’a’in of the Plains, this frozen northern forest. She had no business being here. Her garments, more than adequate to the milder winters in the south, were just not up to the rigors of the cold season here.

Her eyes stung, and not from the icy wind. Home—Warrior Dark, she wanted to be home! Home, away from these alien forests with their unfriendly weather, away from outClansmen with no understanding and no manners . . . home. . . .

Her little mare whickered at her, and strained against her lead rope, her breath steaming and her muzzle edged with frost. She was no fonder of this chilled wilderness than Tarma was. Even the Shin’a’in winter pastures never got this cold, and what little snow fell on them was soon melted. The mare’s sense of what was “right” was deeply offended by all this frigid white stuff.

“Kathal, dester’edra,” Tarma said to the ears that pricked forward at the first sound of her harsh voice. “Gently, windborn-sister. I’m nearly finished here.”

Kessira snorted back at her, and Tarma’s usually solemn expression lightened with an affectionate smile.

“Li’ha’eer, it is ice-demons that dwell in this place, and nothing else.”

When she figured that she had enough of the grass cleared off to at least help to satisfy her mare’s hunger, she heaped the rest of her foragings into the center of the area, topping the heap with a carefully measured portion of mixed grains and a little salt. What she’d managed to find was poor enough, and not at all what her training would have preferred—some dead seed grasses with the heads still on them, the tender tips from the branches of those trees and bushes she recognized as being nourishing, even some dormant cress and cattail roots from the stream. It was scarcely enough to keep the mare from starving, and not anywhere near enough to provide her with the energy she needed to carry Tarma on at the pace she and her partner Kethry had been making up until now.

She loosed little Kessira from her tethering and picketed her in the middle of the space she’d cleared. It showed the measure of the mare’s hunger that she tore eagerly into the fodder, poor as it was. There had been a time when Kessira would have turned up her nose in disdain at being offered such inferior provender.

“Ai, we’ve come on strange times, haven’t we, you and I,” Tarma sighed. She tucked a stray lock of crow-wing-black hair back under her hood, and put her right arm over Kessira’s shoulder, resting against the warm bulk of her. “Me with no Clan but one weirdling outlander, you so far from the Plains and your sibs.”

Not that long ago they’d been just as any other youngling of the nomadic Shin’a’in and her saddle mare; Tarma learning the mastery of sword, song, and steed, Kessira running free except when the lessoning involved her. Both of them had been safe and contented in the heart of Clan Tale’sedrin—true, free Children of the Hawk.

Tarma rubbed her cheek against Kessira’s furry shoulder, breathing in the familiar smell of clean horse that was so much a part of what had been home. Oh, but they’d been happy; Tarma had been the pet of the Clan, with her flute-clear voice and her perfect memory for song and tale, and Kessira had been so well-matched for her rider that she almost seemed the “four-footed sister” that Tarma frequently named her. Their lives had been so close to perfect—in all ways. The king-stallion of the herd had begun courting Kessira that spring, and Tarma had had Dharin; nothing could have spoiled what seemed to be their secure future.

Then the raiders had come upon the Clan; and all that carefree life was gone in an instant beneath their swords.

Tarma’s eyes stung again. Even full revenge couldn’t take away the ache of losing them, all, all—

In one candlemark all that Tarma had ever known or cared about had been wiped from the face of the earth.

“What price your blood, my people? A few pounds of silver? Goddess, the dishonor that your people were counted so cheaply!”

The slaughter of Tale’sedrin had been the more vicious because they’d taken the entire Clan unawares and unarmed in the midst of celebration; totally unarmed, as Shin’a’in seldom were. They had trusted to the vigilance of their sentries.

But the cleverest sentry cannot defeat foul magic that creeps upon him out of the dark and smothers the breath in his throat ere he can cry out.

The brigands had not so much as a drop of honorable blood among them; they knew had the Clan been alerted they’d have had stood the robbers off, even outnumbered as they were, so the bandits’ hired mage had cloaked their approach and stifled the guards. And so the Clan had fought an unequal battle, and so they had died; adults, oldsters, children, all. . . .

“Goddess, hold them—” she whispered, as she did at least once each day. Every last member of Tale’sedrin had died; most had died horribly. Except Tarma. She should have died; and unaccountably had been left alive.

If you could call it living to have survived with everything gone that had made life worth having. Yes, she had been left alive—and utterly, utterly alone. Left to live with a ruined voice that had once been the pride of the Clans, with a ravaged body, and most of all, a shattered heart and mind. There had been nothing left to sustain her but a driving will to wreak vengeance on those who had left her Clanless.

She pulled a brush from an inside pocket of her coat, and began needlessly grooming Kessira while the mare ate. The firm strokes across the familiar chestnut coat were soothing to both of them. She had been left Clanless, and a Shin’a’in Clanless is one without purpose in living. Clan is everything to a Shin’a’in. Only one thing kept her from seeking oblivion and death-willing herself, that burning need to revenge her people.

But vengeance and blood-feud were denied the Shin’a’in—the ordinary Shin’a’in. Else too many of the people would have gone down on the knives of their own folk, and to little purpose, for the Goddess knew Her people and knew their tempers to be short. Hence, Her law. Only those who were the Kal’enedral of the Warrior—the Sword Sworn, outClansmen called them, although the name meant both “Children of Her Sword” and “Her Sword-Brothers”—could cry blood-feud and take the trail of vengeance. That was because of the nature of their Oath to Her—first to the service of the Goddess of the New Moon and South Wind, then to the Clans as a whole, and only after those two to their own particular Clan. Blood-feud did not serve the Clans if the feud was between Shin’a’in and Shin’a’in; keeping the privilege of calling for blood-price in the hands of those by their very nature devoted to the welfare of the Shin’a’in as a whole kept interClan strife to a minimum.

“If it had been you, what would you have chosen, hmm?” she asked the mare. “Her Oath isn’t a light one.” Nor was it without cost—a cost some might think far too high. Once Sworn, the Kal’enedral became weapons in Her hand, and not unlike the sexless, cold steel they wore. Hard, somewhat aloof, and totally asexual were the Sword Sworn—and this, too, ensured that their interests remained Hers and kept them from becoming involved in interClan rivalry. So it was not the kind of Oath one involved in a simple feud was likely to even consider taking.

But the slaughter of the Tale’sedrin was not a matter of private feud or Clan against Clan—this was a matter of more, even, than personal vengeance. Had the brigands been allowed to escape unpunished, would that not have told other wolf-heads that the Clans were not invulnerable—would there not have been another repetition of the slaughter ? That may have been Her reasoning; Tarma had only known that she was able to find no other purpose in living, so she had offered her Oath to the Star-Eyed so that she could pledge her life to revenge her Clan. An insane plan—sprung out of a mind that might be going mad with grief.

There were those who thought she was already mad, who were certain She would accept no such Oath given by one whose reason was gone. But much to the amazement of nearly everyone in the Clan Liha’irden who had succored, healed, and protected her, that Oath had been accepted. Only the shamans had been unsurprised.

She had never in her wildest dreaming guessed what would come of that Oath and that quest for justice.

Kessira finished the pile of provender, and moved on to tear hungrily at the lank, sere grasses. Beneath the thick coat of winter hair she had grown, her bones were beginning to show in a way that Tarma did not in the least like. She left off brushing, and stroked the warm shoulder, and the mare abandoned her feeding long enough to nuzzle her rider’s arm affectionately.

“Patient one, we shall do better by you, and soon,” Tarma pledged her. She left the mare to her grazing and went to check on Kethry’s mule. That sturdy beast was capable of getting nourishment from much coarser material than Kessira, so Tarma had left him tethered amid a thicket of sweetbark bushes. He had stripped all within reach of last year’s growth, and was straining against his halter with his tongue stretched out as far as it would reach for a tasty morsel just out of his range.

“Greedy pig,” she said with a chuckle, and moved him again, giving him a bit more rope this time, and leaving his own share of grain and foraged weeds within reach. Like all his kind he was a clever beast; smarter than any horse save one Shin’a’in-bred. It was safe enough to give him plenty of lead; if he tangled himself he’d untangle himself just as readily. Nor would he eat to foundering, not that there was enough browse here to do that. A good, sturdy, gentle animal, and even-tempered, well suited to an inexperienced rider like Kethry. She’d been lucky to find him.

His tearing at the branches shook snow down on her; with a shiver she brushed it off as her thoughts turned back to the past. No, she would never have guessed at the changes wrought in her life-path by that Oath and her vow of vengeance.

“Jel’enedra, you think too much. It makes you melancholy.”

She recognized the faintly hollow-sounding tenor at the first word; it was her chief sword-teacher. This was the first time he’d come to her since the last bandit had fallen beneath her sword. She had begun to wonder if her teachers would ever come back again.

All of them were unforgiving of mistakes, and quick to chastise—this one more than all the rest put together. So though he had startled her, though she had hardly expected his appearance, she took care not to display it.

“Ah?” she replied, turning slowly to face him. Unfair that he had used his other-worldly powers to come on her unawares, but he himself would have been the first to tell her that life—as she well knew—was unfair. She would not reveal that she had not detected his presence until he spoke.

He had called her “younger sister,” though, which was an indication that he was pleased with her for some reason. “Mostly you tell me I don’t think enough.”

Standing in a clear spot amid the bushes was a man, garbed in fighter’s gear of deepest black, and veiled. The ice-blue eyes, the sable hair, and the cut of his close-wrapped clothing would have told most folk that he was, like Tarma, Shin’a’in. The color of the clothing would have told the more knowledgeable—since most Shin’a’in preferred a carnival brightness in their garments—that he, too, was Sword Sworn; Sword Sworn by custom wore only stark black or dark brown. But only one very sharp-eyed would have noticed that while he stood amid the snow, he made no imprint upon it. It seemed that he weighed hardly more than a shadow.

That was scarcely surprising since he had died long before Tarma was born.

“Thinking to plan is one case; thinking to brood is another,” he replied. “You accomplish nothing but to increase your sadness. You should be devising a means of filling your bellies and those of your jel’suthro’edrin. You cannot reach the Plains if you do not eat.”

He had used the Shin’a’in term for riding beasts that meant “forever-younger-Clanschildren.” Tarma was dead certain he had picked that term with utmost precision, to impress upon her that the welfare of Kessira and Kethry’s mule Rodi were as important as her own—more so, since they could not fend for themselves in this inhospitable place.

“With all respect, teacher, I am . . . at a loss. Once I had a purpose. Now?” She shook her head. “Now I am certain of nothing. As you once told me—”

“Li’sa’eer! Turn my own words against me, will you?” he chided gently. “And have you nothing?”

“My she’enedra. But she is outClan, and strange to me, for all that the Goddess blessed our oath-binding with Her own fire. I know her but little. I—only—”

“What, bright blade?”

“I wish—I wish to go home—” The longing she felt rose in her throat and made it hard to speak.

“And so? What is there to hinder you?”

“There is,” she replied, willing her eyes to stop stinging, “the matter of money. Ours is nearly gone. It is a long way to the Plains.”

“So? Are you not now of the mercenary calling?”

“Well, unless there be some need for blades hereabouts—the which I have seen no evidence for, the only way to reprovision ourselves will be if my she’enedra can turn her skill in magic to an honorable profit. For though I have masters of the best,” she bowed her head in the little nod of homage a Shin’a’in gave to a respected elder, “sent by the Star-Eyed herself, what measure of attainment I have acquired matters not if there is no market for it.”

“Hai’she’li! You should market that silver tongue, jel’enedra!” he laughed. “Well, and well. Three things I have come to tell you, which is why I arrive out-of-time and not at moonrise. First, that there will be storm tonight, and you should all shelter, mounts and riders together. Second, that because of the storm, we shall not teach you this night, though you may expect our coming from this day on, every night that you are not within walls.”

He turned as if to leave, and she called out, “And third?”

“Third?” he replied, looking back at her over his shoulder. “Third—is that everyone has a past. Ere you brood over your own, consider another’s.”

Before she had a chance to respond, he vanished, melting into the wind.

Wrinkling her nose over that last, cryptic remark, she went to find her she’enedra and partner.

Kethry was hovering over a tiny, nearly smokeless fire, skinning a pair of rabbits. Tarma almost smiled at the frown of concentration she wore; she was going at the task as if she were being rated on the results! They were a study in contrasts, she and her outClan blood-sister. Kethry was sweet-faced and curvaceous, with masses of curling amber hair and startling green eyes; she would have looked far more at home in someone’s court circle as a pampered palace mage than she did here, at their primitive hearth. Or even more to the point, she would not have looked out of place as someone’s spoiled, indulged wife or concubine; she really looked nothing at all like any mage Tarma had ever seen. Tarma, on the other hand, with her hawklike face, forbidding ice-blue eyes and nearly sexless body, was hardly the sort of person one would expect a mage or woman like Kethry to choose as a partner, much less as a friend. As a hireling, perhaps—in which case it should have been Tarma skinning the rabbits, for she looked to have been specifically designed to endure hardship.

Oddly enough, it was Kethry who had taken to this trip as if she were the born nomad, and Tarma who was the one suffering the most from their circumstances, although that was mainly due to the unfamiliar weather.

Well, if she had not foreseen that becoming Kal’enedral meant suddenly acquiring a bevy of long-dead instructors, this partnership had come as even more of a surprise. The more so as Tarma had really not expected to survive the initial confrontation with those who had destroyed her Clan.

“Do not reject aid unlooked-for,” her instructor had said the night before she set foot in the bandits’ town. And unlooked-for aid had materialized, in the form of this unlikely sorceress. Kethry, too, had her interests in seeing the murderers brought low, so they had teamed together for the purpose of doing just that. Together they had accomplished what neither could have done alone—they had utterly destroyed the brigands to the last man.

And so Tarma had lost her purpose. Now—now there was only the driving need to get back to the Plains; to return before the Tale’sedrin were deemed a dead Clan. Farther than that she could not, would not think or plan.

Kethry must have sensed Tarma’s brooding eyes on her, for she looked up and beckoned with her skinning knife.

“Fairly good hunting,” Tarma hunched as close the fire as she could, wishing they dared build something large.

“Yes and no. I had to use magic to attract them, poor things.” Kethry shook her head regretfully as she bundled the offal in the skins and buried the remains in the snow to freeze hard. Once frozen, she’d dispose of them away from the camp, to avoid attracting scavengers. “I felt so guilty, but what else was I do to? We ate the last of the bread yesterday, and I didn’t want to chance on the hunting luck of just one of us.”

“You do what you have to, Keth. Well, we’re able to live off the land, but Kessira and Rodi can’t,” Tarma replied. “Our grain is almost gone, and we’ve still a long way to go to get to the Plains. Keth, we need money.”

“I know.”

“And you’re the one of us best suited to earning it. This land is too peaceful for the likes of me to find a job—except for something involving at least a one-year contract, and that’s something we can’t afford to take the time for. I need to get back to the Plains as soon as I can if I’m to raise Tale’sedrin’s banner again.”

“I know that, too.” Kethry’s eyes had become shadowed, the lines around her mouth showed strain. “And I know that the only city close enough to serve us is Mornedealth.”

And there was no doubt in Tarma’s mind that Kethry would rather have died than set foot in that city, though she hadn’t the vaguest notion why. Well, this didn’t look to be the proper moment to ask—

“Storm coming; a bad one,” she said, changing the subject. “I’ll let the hooved ones forage for as long as I dare, but by sunset I’ll have to bring them into camp. Our best bet is going to be to shelter all together because I don’t think a fire is going to survive the blow.”

“I wish I knew where you get your information,” Kethry replied, frown smoothing into a wry half-smile. “You certainly have me beat at weather-witching.”

“Call it Shin’a’in intuition,” Tarma shrugged, wishing she knew whether it was permitted to an outland she’enedra—who was a magician to boot—to know of the veiled ones. Would they object? Tarma had no notion, and wasn’t prepared to risk it. “Think you can get our dinner cooked before the storm gets here?”

“I may be able to do better than that, if I can remember the spells.” The mage disjointed the rabbits, and spitted the carcasses on twigs over the fire. She stripped off her leather gloves, flexed her bare fingers, then held her hands over the tiny fire and began whispering under her breath. Her eyes were half-slitted with concentration and there was a faint line between her eyebrows. As Tarma watched, fascinated, the fire and their dinner were enclosed in a transparent shell of glowing gold mist.

“Very pretty; what’s it good for?” Tarma asked when she took her hands away.

“Well, for one thing, I’ve cut off the wind; for another, the shield is concentrating the heat and the meat will cook faster now.”

“And what’s it costing you?” Tarma had been in Kethry’s company long enough now to know that magic always had a price. And in Kethry’s case, that price was usually taken out of the resources of the spell-caster.

Kethry smiled at her accusing tone. “Nowhere near so much as you might think; this clearing has been used for overnighting a great deal, and a good many of those camping here have celebrated in one way or another. There’s lots of residual energy here, energy only another mage could tap. Mages don’t take the Trade Road often, they take the Couriers’ Road when they have to travel at all.”

“So?”

“So there’s more than enough energy here not only to cook dinner but to give us a little more protection from the weather than our bit of canvas.”

Tarma nodded, momentarily satisfied that her blood-sister wasn’t exhausting herself just so they could eat a little sooner. “Well, while I was scrounging for the hooved ones, I found a bit for us, too—”

She began pulling cattail roots, mallow-pitch, a few nuts, and other edibles from the outer pockets of her coat. “Not a lot there, but enough to supplement dinner, and make a bit of breakfast besides.”

“Bless you! These bunnies were a bit young and small, and rather on the lean side—should this stuff be cooked?”

“They’re better raw, actually.”

“Good enough; want to help with the shelter, since we’re expecting a blow?”

“Only if you tell me what to do. I’ve got no notion of what these winter storms of yours are like.”

Kethry had already stretched their canvas tent across the top and open side of the enclosure of rocks and logs, stuffed brush and moss into the chinks on the inside, packed snow into the chinks from the outside, and layered the floor with pine boughs to keep their own bodies off the snow. Tarma helped her lash the canvas down tighter, then weighted all the loose edges with packed-down snow and what rocks they could find.

As they worked, the promised storm began to give warning of its approach. The wind picked up noticeably, and the northern horizon began to darken. Tarma cast a wary eye at the darkening clouds. “I hope you’re done cooking because it doesn’t look like we have too much time left to get under cover.”

“I think it’s cooked through.”

“And if not, it won’t be the first time we’ve eaten raw meat on this trip. I’d better get the gr

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...