- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Elena Whitstone and her seven brothers, abandoned by her mother, find themselves with a new stepmother. At first she seems more neglectful than evil, until just after Christmas she proves herself to be worse than evil; she is an actual magician, a Master of Water, who attempts to muder Elena's seven brothers when they are skating. When they survive that attempt by transforming into swans, she drives them away.

But the shock of having all of his heirs perish in a frozen pond is too much for Elena's father. He dies, and his widow is abruptly confronted with the inconvenient truth that the estate is entailed, and she not only must leave, she is lawfully in charge of Elena.

Furious, and possessing "only" what was gifted to her during her marriage, the stepmother retreats to Bath, to take up residence in the luxurious townhouse that was bought for her, and resume her former profession as a "Cyprian," a very exclusive courtesan, with Elena reluctantly posing as a page-boy and her servant. Nothing lasts forever, of course, and three years later, Elena is rapidly maturing too much to continue that ruse--and the stepmother is facing the ravages of time. The stepmother concocts a plan to establish an exclusive brothel and regain her wealth by selling Elena to the highest bidder.

Alone, Elena must not only find a way to save herself, but to reverse the spell that has transformed her brothers.

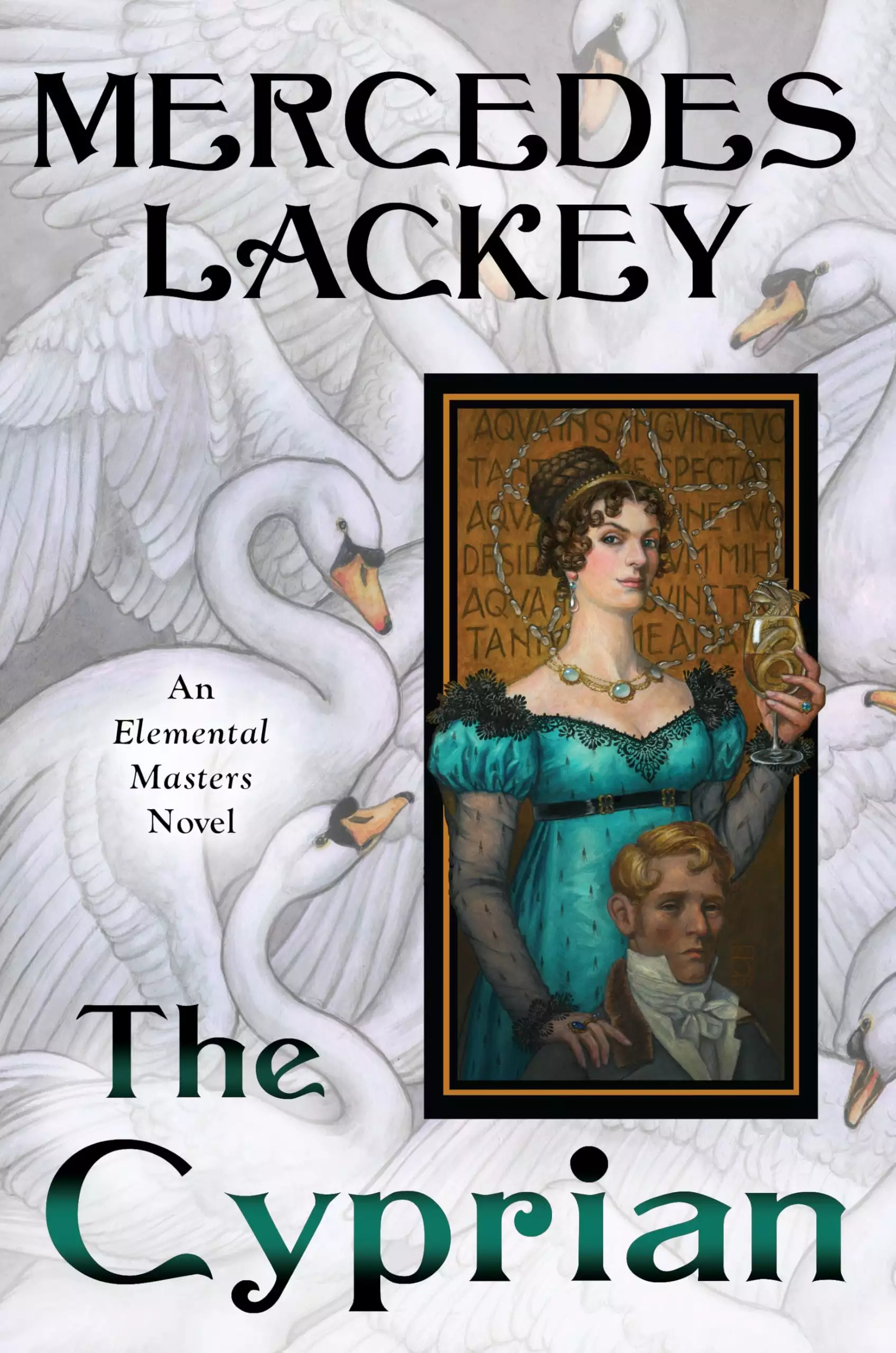

The latest in Mercedes Lackey's Elemental Masters series is a stand-alone romantasy based on Hans Christian Andersen's The Wild Swans.

Release date: December 30, 2025

Publisher: DAW

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Cyprian

Mercedes Lackey

Prologue

FATHER was absent on one of his rare visits to Bath when Benjamin Whitstone heard someone sobbing in his mother’s room. He wasn’t supposed to be in this part of the house; the rooms on this floor in the west wing were reserved for his father, his mother, and important overnight guests. But his tutor, Beecham, had eaten something last night that disagreed violently with him, and without Father about to shame Beecham into at least supervising the oldest children even though he was ill, Ben, Arthur, Carl, David, Emil, and Felix had been left to their own devices. Five-year-old Gustav and Elena, of course, were still under the care and control of Nanny in the nursery, so they were fully occupied with their ABCs and numbers. Carl and David had taken the opportunity to escape into the grounds to play at being highwaymen. Emil and Felix were exploring the attic—also technically forbidden territory, but as long as they didn’t drag what they found up there down into the main house, no one ever bothered to chide them for the transgression. Ben’s twin Arthur was alone in the schoolroom—reading, not studying, although technically, Ben supposed, the English translation of The Odyssey could count as “study.” Mind, they were supposed to be reading it in Greek, but both of them found it heavy going, and often snuck in chances to read the translation they’d found in Father’s library to give them a leg up on the Greek as well as to relish the sheer adventure of it all.

Ben, however, had other things in mind. He’d discovered that the little winged creatures in the house and grounds, the ones that he and the other children were not supposed to talk about in front of anyone but Mama and each other, were perfectly willing to aid and abet his curiosity and explorations.

Fairies, was what the siblings called them, though Mama called them sylphs. She was the one who had warned all the children as soon as they could talk to never let anyone but her know they could see the entrancing creatures.

It was just another thing they were never to do around Father. Always mind your manners, never be outwardly affectionate to anyone or anything. Control your temper at all times. Do not speak unless you are spoken to. Never ask for favors or presents. Master your lessons before play, and if the lessons were not mastered by bedtime, then you would have no playtime the following day. “Children should be seen and not heard, and seen as little as possible.”

Were all fathers like that? It was hard to tell. Certainly Father had no interest in them except when he briefly lined up the boys (not Elena), presented them to guests, and boasted about their intelligence. He never boasted about their looks or other accomplishments, although, in Ben’s limited experience, he and his siblings were quite handsome children. Maybe Father ignored how they

looked because they all looked like Mama, blond and lithe, and not like him, darker haired and square faced, with an oddly high forehead and tiny eyes.

Ben often wondered why Father had had children in the first place, since he thought so little of them as to forget them for weeks and months at a time.

And Ben often wondered why Mama had ever married Father in the first place. Every time he was around it was as if the light that was inside her when she was alone or only with her children was extinguished.

At least when Father or the servants weren’t about, the fairies were only too willing to amuse and be amusing. Recently, mind inflamed by recent history lessons about the Tudors that included mentions of secret passages and priest’s holes and other equally entrancing things, he’d enlisted their help in ferreting out hiding places all over Whitstone Manor. So far he had not uncovered any secret passages, but now he knew where there were some concealed doors that let out into the servants’ stairs and passages, and a few smaller places where things were hidden away or otherwise out of reach. So far he hadn’t found anything particularly exciting—certainly no treasure—but knowing that he was privy to secrets the others weren’t was reward enough to keep hunting.

His first thought when he heard the crying was that one of the servant girls had hurt herself, or had been beaten by the housekeeper. The housekeeper was not normally a cruel woman, but she was very strict, and if a servant girl was slacking, or suspected of dallying with one of the menservants, or had broken something through carelessness, Mrs. Farthingworth did not hesitate to use the birch on her. Whenever Ben found one of the girls crying—provided he wasn’t in a position to be discovered and lectured, usually by the tutor—he’d do his best to comfort her. A nice comfit or sugarplum usually did the trick, along with a kind word and a loaned handkerchief. Not one of his good ones, of course; one of the ones little Elena was using to

practice her sewing on. The loans always came back neatly washed and pressed, but there was no point in getting a lecture over “losing” a good handkerchief that was supposed to be in the laundry when one of Elena’s gifts served the same purpose and wouldn’t be missed.

He eased the door open carefully and peeked inside, only to find his mother hunched over a hassock, blue skirts spread about her, sobbing inconsolably. “Mama!” he called, startled. “Mama, what is wrong?”

His mother started like a nervous deer and looked up, blue eyes red and swollen, a curl of golden hair escaping from the careful arrangement her lady’s maid would have put it into this morning. The door to her balcony was wide open, summer sunlight streaming through it, illuminating her grief unmistakably. Even so, Ben thought, she was the most beautiful lady he knew.

“Ben!” she replied, recognizing it was him rather than his twin—something she and no one else except his siblings seemed to be able to do. “What are you doing here? Shouldn’t you—”

“Beecham is sick, and never mind that now,” he replied, running to her and falling to his knees beside her. Her delicate perfume, something he could never identify, wafted over him. “Mama, whatever is wrong? Are you hurt? Did you lose something?”

Those simple words seemed to send her into a world of sorrow, and she buried her face in her hands. “Yes—no—yes!” she sobbed. “Yes, but it was taken from me before you were born, and—and—and—I cannot bear this anymore! I need it! I need it more than I can say! If I do not find it, I shall surely die!”

Ben knew what Father would have said to such a statement: Don’t be ridiculous, Elsa. You’re not going to die. But Father had an intense dislike for tears, and what he called “vapors” and “hysterics,” to the point that even five-year-old Elena knew better than to cry around him, and the boys had learned to endure

any amount of pain without expressing anything but verbal discomfort. But Ben was not Father, who could sail past a weeping housemaid without anything other than a sharp word and the instruction to “take yourself to Mrs. Farthingworth if you cannot control yourself,” and so he responded by awkwardly patting his mother on the shoulder and saying, “Mama, don’t cry. I’m very good at finding things that are lost. I’ll help you find it, whatever it is.”

She took her hands from her face and gave him a watery and insincere smile. “You’re a dear boy, Ben, but you’ll never find it. It is not lost. Your father took it from me to keep me with him, and has hidden it away from me on purpose. He knew very well what he was doing.”

The words—the phrasing—were very odd. Keep me with him, and He knew what he was doing. And that was when Ben had one of those moments of inspiration and certainty that came to him without any warning—but were always right. The memory of finding something inexplicable in one of those hiding places . . . something that could only be connected with Mama, for there was no one else in the household who could have been connected with such an odd but entrancing object. “Father hid it from you? What was it?” he asked, then without waiting for an answer, continued, “Was it something like a cloak of white feathers?”

His mother sat swiftly erect, gasping. “Yes!” she exclaimed. “But how—”

“Because I saw it,” he said. “I know where it is.”

“Take me to it!” she interrupted, springing to her feet. “Take me to it right now!”

He, too, shot to his feet, grabbed her hand, and pulled her along behind him. It wasn’t far, after all, just in Father’s rooms. He pulled her to a section of the wainscoted wall in the bedroom, and carefully counted dark wooden panels from the left end where the two walls met. Two, three, and four—he pressed in the carved rose at the intersection of the fourth and fifth panel, and turned it. It had taken quite

a bit of trial and error to figure out just what he should do when the little fairy had shown him where there was a hidden space, but he’d managed to figure it out. There was a click, and the fourth panel popped out, just a bit. He pulled it open, showing the yellowed silk lining of the storage area behind the panel, and there, pressed into the space, was what he had guessed to be a cloak made out of pure white feathers. Why anyone should want such a thing—especially Father—he’d had no idea, but there it had been when he had first found it, and there it was now.

With a faint cry, his mother buried both hands in the feathers, and lifted it out of its silk prison.

And then, paying no heed to Ben, she turned and ran—ran as if she was running away from peril.

He followed her, calling, “Mama, Mama, wait!” but he might as well have been voiceless. She swung the cloak over her shoulders as she ran, and pulled up the hood. She was entirely enveloped in it by the time she reached the door of her room, and by the time Ben reached that same spot, he saw her racing through the door to her balcony. She paused there for just a moment—and then jumped.

Too struck with horror to utter a sound, he raced to the balcony himself and looked down, expecting to see her sprawled on the pavement of the walk beneath, dead or gravely injured.

But there was nothing there.

Frantic and baffled now, he looked up, in time to see a pure white swan beating her wings in rapid flight away—away from the mansion and into the east.

There were no swans on the Whitstone estate. Father wouldn’t allow them. He had the gamekeeper shoot at them to frighten them, or trap them and carry them off. He said it was because all swans belonged to the king, but

Ben just knew that wasn’t the reason. And why would a swan have been so close to the manor that it could have jumped from the balcony to take wing?

“M-mama?” he stammered.

But the swan did not answer, and did not look back. In moments, she was out of sight.

Ben had always been the quickest of the children; even in a crisis his mind remained clear, and his thoughts logical.

Mama can see the fairies and told us not to tell Father we could. Fairies are magic. Mama could be magic, too.

Nanny told us stories about the seal people who shed their skins to become human. There could be swan-people too, like them. And in the stories, men who want a seal-person wife, because they are so beautiful, steal their skins and hide them away. Is that what happened? Did Father steal a swan-girl’s skin so he could have a beautiful wife? Certainly Mama was the most beautiful lady he had ever seen, and there were plenty of beautiful women who came to Father’s parties with their husbands or parents. More than once, when he shouldn’t have been eavesdropping, he’d heard other men congratulate Father on his “conquest.” Father always preened when such compliments came his way, gloating almost.

Gloating, because he didn’t win her, and it wasn’t even an arranged marriage. Gloating because he stole her away from her home and people! So much came clear in that moment: why Mama had always been so subdued, why she showed Father obedience but never affection, and why Father treated her more like a treasured possession than a beloved wife. Of course she was subdued! And obedient! She had been a prisoner!

Ben had never cared much for his father, which was unfilial, but nevertheless a fact—but in that moment, he hated the man. To hold someone

captive against their will like that—someone who was used to being wild and free and magical—someone as kind and sweet as his Mama—it was an abomination!

But in that moment he also understood that Mama was surely gone, gone forever. He knew from the behavior of the fairies that it wasn’t wise to count on their affections; Nanny’s tales of the seal-wives told the same story. When the choice was between her children and her freedom, a magical creature would always choose her freedom.

And now he was torn, torn between grief and sudden caution. Father would be enraged when he found this out, and he would find it out, because Mama would be missing when he returned, and so would her magical cloak. So he dared not show his grief to anyone, at least not until Mama’s disappearance was known to the household. Then he could cry with feigned confusion like the rest of them. He could not confide what had just happened, even to his twin. No one could know where Mama had gone, only that she was inexplicably missing. He had to give himself an alibi, so no suspicion would fall on him. And he had to close up that panel, so Father would never know how Mama had found her cloak.

It was a very good thing he had never confided his hunt for hidden spaces to his twin. He was a much better liar than Arthur; if Father burst into a rage, Arthur would give away anything he knew.

Then grief took over for a time, the loss of Mama obliterating the anger he felt at Father. He dropped to his knees beside the hassock where Mama had been crying, and allowed himself a moment of inconsolable blubbering.

When the worst of his sorrow had been purged, he washed his face in Mama’s washbasin, returning to Father’s room to close the panel as if it had never been opened. Then, he slipped down a servants’ stair to the garden to join Carl and David in the grounds. It would be a lot easier not to cry if he

was playing at highwayman. He’d even volunteer to be the victim; then, if his voice faltered or he started to tremble, they’d take it for play-acting. It would be hard not to tell the others. The servants would certainly set up a hue and cry when they couldn’t find Mama anywhere by teatime, and his siblings’ hearts would be broken when she couldn’t be found, but Father’s wrath would have nowhere to fall as long as he didn’t know who to blame.

Things would probably be horrid—well, they were horrid, because Mama was never coming back—but as he paused on the edge of the garden to look for Carl and David, then cast his eyes to the sky for one last resigned look, he knew he could not have done anything else.

“I’d do it again, Mama,” he said, though no one could hear him. “I’d do it again.” ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...