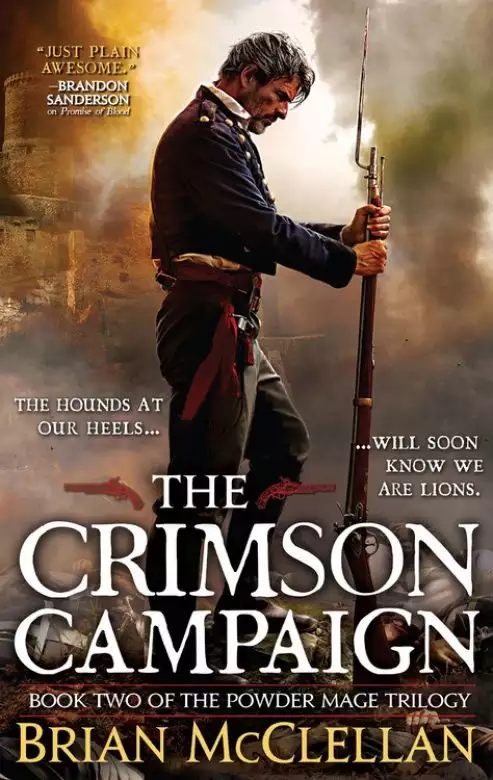

The Crimson Campaign

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

But the threats are closer to home...

Who will lead the charge?

Release date: May 6, 2014

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 628

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Crimson Campaign

Brian McClellan

Adamat stood perfectly still in the middle of a deep hedgerow outside of his own summer house and stared through the windows at the men in the dining room. The house was a two-story, three-bedroom affair sitting by itself in the woods at the end of a dirt path. It was a twenty-minute walk into town from here. Unlikely anyone would hear gunshots.

Or screams.

Four of Lord Vetas’s men milled about in the dining room, drinking and playing cards. Two of them were large and well-muscled as draft horses. A third was of middling height, with a heavy gut hanging out of his shirt and a thick black beard.

The final man was the only one Adamat recognized. He had a square face and a head that was almost comically small. His name was Roja the Fox, and he was the smallest boxer in the bareknuckle-boxing circuit run by the Proprietor back in Adopest. He could move faster than most boxers, by necessity, but he wasn’t popular with the crowds and did not fight often. What he was doing here, Adamat had no idea.

What he did know was that he feared for the safety of his children—especially his daughters—with a group of malcontents like this.

“Sergeant,” Adamat whispered.

The hedgerow rustled, and Adamat caught a glimpse of Sergeant Oldrich’s face. He had a sharp jawline, and the dim moonlight betrayed the bulge of tobacco in one cheek. “My men are in place,” Oldrich responded. “Are they all in the dining room?”

“Yes.” Adamat had observed the house for three days now. All that time he’d stood by and watched these men yell at his children and smoke cigars in his house, dropping ash and spilling beer on Faye’s good tablecloth. He knew their habits.

He knew that the fat, bearded one stayed upstairs, keeping an eye on the children all day. He knew the two big thugs escorted the children to the outhouse while Roja the Fox kept watch. He knew the four of them wouldn’t leave the children by themselves until after dark, when they’d set up their nightly card game on the dining room table.

He also knew that in three days, he’d seen no sign of his wife or his oldest son.

Sergeant Oldrich pressed a loaded pistol into Adamat’s hand. “Are you sure you want to lead on this? My men are good. They’ll get the children out unharmed.”

“I’m sure,” Adamat said. “They’re my family. My responsibility.”

“Don’t hesitate to pull the trigger if they head toward the stairs,” Oldrich said. “We don’t want them to take hostages.”

The children were already hostages, Adamat wanted to say. He bit back his words and smoothed the front of his shirt with one hand. The sky was cloudy, and now that the sun had set there would be no light to betray his presence to those inside. He stepped out of the hedgerow and was suddenly reminded of the night he’d been summoned to Skyline Palace. That was the night all this had begun: the coup, then the traitor, then Lord Vetas. Silently, he cursed Field Marshal Tamas for drawing him and his family into this.

Sergeant Oldrich’s soldiers crept out across the worn dirt path with Adamat, heading toward the front of the house. Adamat knew there were another eight behind the house. Sixteen men in total. They had the numbers. They had the element of surprise.

Lord Vetas’s goons had Adamat’s children.

Adamat paused at the front door. Adran soldiers, their dark-blue uniforms almost impossible to see in the darkness, took up spots beneath the dining room windows, their muskets at the ready. Adamat looked down at the door. Faye had chosen this house, instead of one closer to town, in part because of the door. It was a sturdy oak door with iron hinges. She felt that a strong door made her family safer.

He’d never had the heart to tell her the door frame was riddled with termites. In fact, Adamat had always meant to have it replaced.

Adamat stepped back and kicked right next to the doorknob.

The rotten wood exploded with the impact. Adamat ducked into the front hall and brought his pistol up as he rounded the corner.

All four of the goons burst into action. One of the big men leapt toward the back doorway leading to the staircase. Adamat held his pistol steady and fired and the man dropped.

“Don’t move,” Adamat said. “You’re surrounded!”

The remaining three goons stared back at him, frozen in place. He saw their eyes go to his spent pistol, and then they all went for him at once.

The volley of musket balls from the soldiers outside burst the window and glass showered the room like frost. The remaining goons went down, except for Roja the Fox. He stumbled toward Adamat with a knife drawn, blood soaking the sleeve of one arm.

Adamat reversed the grip on his pistol and brought the butt down on Roja’s head.

Just like that, it was over.

Soldiers spilled into the dining room. Adamat pushed past them and bolted up the stairs. He checked the children’s rooms first: all empty. Finally, the master bedroom. He flung the door open with such force it nearly flew off the hinges.

The children were huddled together in the narrow space between the bed and the wall. The older siblings embraced the younger ones, shielding them in their arms as best they could. Seven frightened faces stared up at Adamat. One of the twins was crying, no doubt from the crack of the muskets. Silent tears streamed down his chubby cheeks. The other poked his head out timidly from his hiding place beneath the bed.

Adamat breathed a sigh of relief and fell to his knees. They were alive. His children. He felt the tears come unbidden as he was mobbed by small bodies. Tiny hands reached out and touched his face. He threw his arms wide, grabbing as many of them as possible and pulling them closer.

Adamat wiped the tears from his cheeks. It wasn’t seemly to cry in front of the children. He took a great breath to compose himself and said, “I’m here. You’re safe. I’ve come with Field Marshal Tamas’s men.”

Another round of happy sobs and hugs followed before Adamat was able to restore order.

“Where is your mother? Where’s Josep?”

Fanish, his second oldest, helped to shush the other children. “They took Astrit a few weeks ago,” she said, pulling at her long black braid with shaking fingers. “Just last week they came and took Mama and Josep.”

“Astrit is safe,” Adamat said. “Don’t worry. Did they say where they were taking Mama and Josep?”

Fanish shook her head.

Adamat felt his heart fall, but he didn’t let it show on his face. “Did they hurt you? Any of you?” He was most concerned for Fanish. She was fourteen, practically a woman. Her shoulders were bare beneath her thin nightgown. Adamat searched for bruises and breathed a word of thanks there were none.

“No, Papa,” Fanish said. “I heard the men talking. They wanted to, but…”

“But what?”

“A man came when they took away Mama and Josep. I didn’t hear his name, but he was dressed as a gentleman and he spoke very quietly. He told them that if they touched us before he gave them permission, he’d…” She trailed off and her face went pale.

Adamat patted her on the cheek. “You’ve been very brave,” he reassured her gently. Inside, Adamat fumed. Once Adamat was no longer any use to him, Vetas no doubt would have turned those goons loose on the children without a second thought.

“I’m going to find them,” he said. He patted Fanish on the cheek again and stood up. One of the twins grabbed his hand.

“Don’t go,” he begged.

Adamat wiped the little one’s tears. “I’ll be right back. Stay with Fanish.” Adamat wrenched himself away. There was still one more child and his wife to save—more battles to win before they were all safely reunited.

He found Sergeant Oldrich just outside the upstairs bedroom, waiting respectfully with his hat in his hands.

“They took Faye and my oldest son,” Adamat said. “The rest of the children are safe. Are any of those animals alive?”

Oldrich kept his voice low so the children wouldn’t overhear. “One of them took a bullet to the eye. Another, the heart. It was a lucky volley.” He scratched the back of his head. Oldrich wasn’t old by any means, but his hair was already graying just above his ears. His cheeks were flushed from the storm of violence. His voice, though, was even.

“Too lucky,” Adamat said. “I needed one of them alive.”

“One’s alive,” Oldrich said.

When Adamat reached the kitchen, he found Roja sitting in one of the chairs, his hands tied behind his back, bleeding from bullet wounds to the shoulder and hip.

Adamat retrieved a cane from the umbrella stand beside the front door. Roja stared balefully at the floor. He was a boxer, a fighter. He wouldn’t go down easy.

“You’re lucky, Roja,” Adamat said, pointing to the bullet wounds with the tip of his cane. “You might survive these. If you receive medical attention quickly enough.”

“I know you?” Roja said, snorting. Blood speckled his dirty linen shirt.

“No, you don’t. But I know you. I’ve watched you fight. Where’s Vetas?”

Roja turned his neck to the side and popped it. His eyes held a challenge. “Vetas? Don’t know him.”

Beneath the feigned ignorance, Adamat thought he caught a note of recognition in the boxer’s voice.

Adamat placed the tip of his cane against Roja’s shoulder, right next to the bullet wound. “Your employer.”

“Eat shit,” Roja said.

Adamat pressed on his cane. He could feel the ball still in there, up against the bone. Roja squirmed. To his credit, he didn’t make a sound. A bareknuckle boxer, if he was any good, learned to embrace pain.

“Where’s Vetas?”

Roja didn’t respond. Adamat stepped closer. “You want to live through the night, don’t you?”

“He’ll do worse to me than you ever could,” Roja said. “Besides, I don’t know nothin’.”

Adamat stepped away from Roja, turning his back. He heard Oldrich step forward, followed by the heavy thump of a musket butt slamming into Roja’s gut. He let the beating continue for a few moments before turning back and waving Oldrich away.

Roja’s face looked like he’d been through a few rounds with SouSmith. He doubled over, spitting blood.

“Where did they take Faye?” Tell me, Adamat begged silently. For your sake, hers, and mine. Tell me where she is. “The boy, Josep? Where is he?”

Roja spit on the floor. “You’re him, aren’t you? The father of these stupid brats?” He didn’t wait for Adamat to answer. “We were gonna bugger all those kids. Startin’ with the small ones first. Vetas wouldn’t let us. But your wife…” Roja ran his tongue along his broken lips. “She was willing. Thought we’d go easy on the babies if she took us all.”

Oldrich stepped forward and slammed the butt of his musket across Roja’s face. Roja jerked to one side and let out a choked groan.

Adamat felt his whole body shaking with rage. Not Faye. Not his beautiful wife, his friend and partner, his confidante and the mother of his children. He held up his hand when Oldrich wound up to hit Roja again.

“No,” Adamat said. “That’s just an average day for this one. Get me a lantern.”

He grabbed Roja by the back of the neck and dragged him out of the chair, pushing him outside through the back door. Roja stumbled into an overgrown rosebush in the garden. Adamat lifted him to his feet, sure to use his wounded shoulder, and shoved him along. Toward the outhouse.

“Keep the children inside,” Adamat said to Oldrich, “and bring a few men.”

The outhouse was wide enough for two seats, a necessity for a household with nine children. Adamat opened the door while two of Oldrich’s soldiers held Roja up between them. He took a lantern from Oldrich and let it illuminate the inside of the outhouse for Roja to see.

Adamat grabbed the board that covered the outhouse hole and tossed it on the ground. The smell was putrid. Even after sundown the walls crawled with flies.

“I dug this hole myself,” Adamat said. “It’s eight feet deep. I should have cut a new one years ago, and the family has been using it a lot lately. They were here all summer.” He shined the lantern into the hole and gave an exaggerated sniff. “Almost full,” he said. “Where is Vetas? Where did they take Faye?”

Roja sneered at Adamat. “Go to the pit.”

“We’re already there,” Adamat said. He grabbed Roja by the back of the neck and forced him into the outhouse. It was barely big enough for the two of them. Roja struggled, but Adamat’s strength was fueled by his rage. He kicked Roja’s knees out from under him and shoved the boxer’s head into the hole.

“Tell me where he is,” Adamat hissed.

No answer.

“Tell me!”

“No!” Roja’s voice echoed in the box that formed the outhouse seat.

Adamat pushed on the back of Roja’s head. A few more inches and Roja would get a face full of human waste. Adamat choked back his own disgust. This was cruel. Inhuman. Then again, so was taking a man’s wife and children hostage.

Roja’s forehead touched the top of the shit and he let out a sob.

“Where is Vetas? I won’t ask again!”

“I don’t know! He didn’t tell me anything. Just paid me to keep the kids here.”

“How were you paid?” Adamat heard Roja retch. The boxer’s body shuddered.

“Krana notes.”

“You’re one of the Proprietor’s boxers,” Adamat said. “Does he know about any of this?”

“Vetas said we were recommended. No one hires us for the job unless the Proprietor gives the go-ahead.”

Adamat gritted his teeth. The Proprietor. The head of the Adran criminal world, and a member of Tamas’s council. He was one of the most powerful men in Adro. If he knew about Lord Vetas, it could mean he’d been a traitor all along.

“What else do you know?”

“I barely spoke twenty words with the guy,” Roja said. His words were coming out in broken gasps as he sputtered through his tears. “Don’t know anything else!”

Adamat struck Roja on the back of the head. He sagged, but he was not unconscious. Adamat lifted him by his belt and shoved his face down into the muck. He lifted him again and pushed. Roja flailed, his legs kicking hard as he tried to breathe through the piss and shit. Adamat grabbed the boxer by the ankles and pushed down, jamming Roja in the hole.

Adamat turned and walked out of the outhouse. He couldn’t think through his fury. He was going to destroy Vetas for putting his wife and children through this.

Oldrich and his men stood by, watching Roja drown in filth. One of them looked ill in the dim lantern light. Another was nodding in approval. The night was quiet now, and Adamat could hear the steady chirp of crickets in the forest.

“Aren’t you going to ask him more questions?” Oldrich said.

“He said himself, he doesn’t know anything else.” Adamat felt his stomach turn and he looked back at Roja’s kicking legs. The mental image of Roja forcing himself on Faye almost stopped Adamat, and then he said to Oldrich, “Pull him out before he dies. Then ship him to the deepest coal mine you can find on the Mountainwatch.”

Adamat swore to do worse to Vetas when he caught him.

Field Marshal Tamas stood above Budwiel’s southern gate and surveyed the Kez army. This wall marked the southernmost point of Adro. If he tossed a stone in front of him, it would land on Kez soil, perhaps rolling down the slope of the Great Northern Road until it reached the Kez pickets on the edge of their army.

The Gates of Wasal, a pair of five-hundred-foot-tall cliffs, rose to either side of him, divided by thousands of years of flowing water coming out of the Adsea, cutting through Surkov’s Alley, and feeding the grain fields of the Amber Expanse in northern Kez.

The Kez army had left the smoldering ruins of South Pike Mountain only three weeks ago. Official reports estimated the number of men in the army that had besieged Shouldercrown as two hundred thousand soldiers, accompanied by camp followers that swelled that number to almost three-quarters of a million.

His scouts told him that the total number was over a million now.

A small part of Tamas cowered at such a number. The world had not seen an army of that size since the wars of the Bleakening over fourteen hundred years ago. And here it was at his doorstep, trying to take his country from him.

Tamas could recognize a new soldier on the walls by how loud they gasped upon seeing the Kez army. He could smell the fear of his own men. The anticipation. The dread. This was not Shouldercrown, a fortress easily held by a few companies of soldiers. This was Budwiel, a trading city of some hundred thousand people. The walls were in disrepair, the gates too numerous and too wide.

Tamas did not let that fear show on his own face. He didn’t dare. He buried his tactical concerns; the terror he felt that his only son lay in Adopest deep in a coma; the pain that still ached in his leg despite the healing powers of a god. Nothing showed on his countenance but contempt for the audacity of the Kez commanders.

Steady footfalls sounded on the stone stairs behind him, and Tamas was joined by General Hilanska, the commander of Budwiel’s artillery and the Second Brigade.

Hilanska was an extremely portly man of about forty years old, a widower of ten years, and a veteran of the Gurlish Campaigns. He was missing his left arm at the shoulder, taken clean off by a cannonball thirty years ago when Hilanska was not yet a captain. He had never let his arm nor his weight affect his performance on a battlefield, and for that alone he had Tamas’s respect. Never mind that his gun crews could knock the head off a charging cavalryman at eight hundred yards.

Among Tamas’s General Staff, most of whom had been chosen for their skill and not their personalities, Hilanska was the closest thing Tamas had to a friend.

“Been watching them gather there for weeks and it still doesn’t cease to impress me,” Hilanska said.

“Their numbers?” Tamas asked.

Hilanska leaned over the edge of the wall and spit. “Their discipline.” He removed his looking glass from his belt and slid it open with a well-practiced jerk of his one hand, then held it up to his eye. “All those damned paper-white tents lined up as far as the eye can see. Looks like a model.”

“Lining up a half-million tents doesn’t make an army disciplined,” Tamas said. “I’ve worked with Kez commanders before. In Gurla. They keep their men in line with fear. It makes for a clean and pretty camp, but when armies clash, there’s no steel in their spine. They break by the third volley.” Not like my men, he thought. Not like the Adran brigades.

“Hope you’re right,” Hilanska said.

Tamas watched the Kez sentries make their rounds a half mile away, well in range of Hilanska’s guns, but not worth the ammunition. The main army camped almost two whole miles back; their officers feared Tamas’s powder mages more than they did Hilanska’s guns.

Tamas gripped the lip of the stone wall and opened his third eye. A wave of dizziness passed over him before he could see clearly into the Else. The world took on a pastel glow. In the distance there were lights, glimmering like the fires of an enemy patrol at night—the glow of Kez Privileged and Wardens. He closed his third eye and rubbed at his temple.

“You’re still thinking about it, aren’t you?” Hilanska asked.

“What?”

“Invading.”

“Invade?” Tamas scoffed. “I’d have to be mad to launch an attack against an army ten times our size.”

“You’ve got that look to you, Tamas,” Hilanska said. “Like a dog pulling at its chain. I’ve known you too long. You’ve made no secret that you intend to invade Kez given the opportunity.”

Tamas eyed those pickets. The Kez army was set so far back it would be almost impossible to catch them unawares. The terrain gave no good cover for a night attack.

“If I could get the Seventh and Ninth in there with the element of surprise, I could carve through the heart of their army and be back in Budwiel before they knew what hit them,” Tamas said quietly. His heart quickened at the thought. The Kez were not to be underestimated. They had the numbers. They still had a few Privileged, even after the Battle of Shouldercrown.

But Tamas knew what his best brigades were capable of. He knew Kez strategies, and he knew their weaknesses. Kez soldiers were levies from their immense peasant population. Their officers were nobles who’d bought their commissions. Not like his men: patriots, men of steel and iron.

“A few of my boys did some exploring,” Hilanska said.

“They did?” Tamas quelled the annoyance of having his thoughts interrupted.

“You know about Budwiel’s catacombs?”

Tamas grunted in acknowledgment. The catacombs stretched under the West Pillar, one of the two mountains that made up the Gates of Wasal. They were a mixture of natural and man-made caverns used to house Budwiel’s dead.

“They’re off limits to soldiers,” Tamas said, unable to keep the reproach from his voice.

“I’ll deal with my boys, but you might want to hear what they have to say before we have them flogged.”

“Unless they discovered a Kez spy ring, I doubt it’s relevant.”

“Better,” Hilanska said. “They found a way for you to get your men into Kez.”

Tamas felt his heart jump at the possibility. “Take me to them.”

Taniel stared at the ceiling only a foot above him, counting each time he swung, side to side, in the hemp-rope hammock, listening to the Gurlish pipes that filled the room with a soft, whistling music.

He hated that music. It seemed to echo in his ears, all at once too soft to hear well but loud enough to make him grind his molars together. He lost count of the hammock swings somewhere around ten and exhaled. Warm smoke curled out from between his lips and against the crumbling mortar in the ceiling. He watched the smoke escape the roof of his niche and swirl into the middle of the mala den.

There were a dozen such niches in the room. Two were occupied. In the two weeks he’d been there, Taniel had yet to see the occupants get up to piss or eat or do anything other than suck on the long-stemmed mala pipes and flag the den’s owner over for a refill.

He leaned over, his hand reaching for a refill for his own mala pipe. The table next to his hammock held a plate with a few scraps of dark mala, an empty purse, and a pistol. He couldn’t remember where the pistol came from.

Taniel gathered the bits of mala together into one small, sticky ball and pushed it into the end of his pipe. It lit instantly, and he took a long pull into his lungs.

“Want more?”

The den’s owner sidled up to Taniel’s hammock. He was Gurlish, his skin brown but not as dark as a Deliv’s, with a lighter tone under his eyes and on his palms. He was tall, like most Gurlish, and skinny, his back bent from years of leaning into the niches of his mala den to clean them out or light an addict’s pipe. His name was Kin.

Taniel reached for his purse, wiggled his fingers around inside before remembering that it was empty. “No money,” he said, his own voice ragged in his ears.

How long had he been here? Two weeks, Taniel decided after putting his mind to the question. More importantly, how did he get here?

Not here, the mala den, but here in Adopest. Taniel remembered the fight on top of Kresimir’s palace as Ka-poel destroyed the Kez Cabal, and he remembered pulling the trigger of his rifle and watching a bullet take the god Kresimir in the eye.

It was all darkness after that until he woke up, covered in sweat, Ka-poel straddling him with fresh blood on her hands. He remembered bodies in the hallway of the hotel—his father’s soldiers with an unfamiliar insignia on their jackets. He’d left the hotel and stumbled here, where he’d hoped to forget.

Of course, if he still remembered all that, then the mala wasn’t doing its job.

“Army jacket,” Kin said, fingering his lapel. “Your buttons.”

Taniel looked down at the jacket he wore. It was Adran-army dark blue, with silver trim and buttons. He’d taken it from the hotel. It wasn’t his—too big. There was a powder mage pin—a silver powder keg—pinned to the lapel. Maybe it was his. Had he lost weight?

The jacket had been clean two days ago. He remembered that much. Now it was stained with drool, bits of food, and small burns from mala embers. When the pit had he eaten?

Taniel pulled his belt knife and took one of the buttons in his fingers. He paused. Kin’s daughter walked through the room. She wore a faded white dress, clean despite the squalor of the den. She must have been a few years older than Taniel, but no children clung to her skirts.

“Do you like my daughter?” Kin asked. “She will dance for you. Two buttons!” He held up two fingers for emphasis. “Much prettier than the Fatrastan witch.”

Kin’s wife, sitting in the corner and playing the Gurlish pipes, stopped the music long enough to say something to Kin. They exchanged a few words in Gurlish, then Kin turned back to Taniel. “Two buttons!” he reiterated.

Taniel cut a button loose and put it in Kin’s hand. Dance, eh? Taniel wondered if Kin had a strong enough grasp of Adran for euphemism, or if dance was indeed all she’d do.

“Maybe later,” Taniel said, settling back in the hammock with a fresh ball of mala the size of a child’s fist. “Ka-poel isn’t a witch. She’s…” He paused, trying to figure out a way to describe her to a Gurlish. His thoughts moved slowly, sluggish from the mala. “All right,” he conceded. “She’s a witch.”

Taniel topped off his mala pipe. Kin’s daughter was watching him. He returned her open stare with a half-lidded gaze. She was pretty, by some standards. Too tall by far for Taniel, and much too gaunt—most Gurlish were. She stayed there, laundry balanced on her hip, until her father shooed her out.

How long had it been since he’d had a woman?

A woman? He laughed, smoke curling out his nose. The laugh ended in a cough and received no more than a curious glance from Kin. No, not a woman. The woman. Vlora. How long had it been? Two and a half years now? Three?

He sat back up and fished around in his pocket for a powder charge, wondering where Vlora was now. Probably still with Tamas and the rest of the powder cabal.

Tamas would want Taniel back on the front line.

To the pit with that. Let Tamas come to Adopest looking for Taniel. The last place he’d look was a mala den.

There wasn’t a powder charge in Taniel’s pocket. Ka-poel had cleaned him out. He’d not had a smidgen of powder since she brought him out of that goddamned coma. Not even his pistol was loaded. He could go out and get some. Find a barracks, show them his powder-mage pin.

The very idea of getting out of the hammock made his head spin.

Ka-poel came down the steps into the mala den just as Taniel was beginning to drift off. He kept his eyes mostly closed, the smoke curling from his lips. She stopped and examined him.

She was short, her features petite. Her skin was white, with ashen freckles and her red hair was no more than an inch long. He didn’t like it so short, it made her look boyish. No mistaking her for a boy, Taniel thought as she shrugged out of her long black duster. Underneath she wore a white sleeveless shirt, scrounged from who-knew-where, and close-fitting black pants.

Ka-poel touched Taniel’s shoulder. He ignored her. Let her think him asleep, or too deep in a mala haze to notice her. All the better.

She reached out and squeezed his nose shut with one hand, pushing his mouth closed with the other.

He jerked up, taking a breath when she let go. “What the pit, Pole? Trying to kill me?”

She smiled, and it wasn’t the first time under the mala haze that he’d stared into those glass-green eyes with less than proper thoughts. He shook them away. She was his ward. He was her protector. Or was it the other way around? She was the one who’d done the protecting up on South Pike.

Taniel settled back into the hammock. “What do you want?”

She held up a thick pad of paper, bound in leather. A sketchbook. To replace the one lost on South Pike Mountain. He felt a pang at that. Sketches from eight years of his life. People he’d known, many of them long dead. Some friends, some enemies. Losing that sketchbook hurt almost as much as losing his genuine Hrusch rifle.

Almost as much as…

He pushed the stem of his mala pipe between his teeth and sucked in hard. He shivered as the smoke burned his throat and lungs and seeped into his body, deadening the memories.

When he reached out for the sketchbook, he saw that his hand was shaking. He snatched it back quickly.

Ka-poel’s eyes narrowed. She set the sketchbook on his stomach, followed by a pack of charcoal pencils. Finer sketching tools than he’d ever had in Fatrasta. She pointed at them, and mimed him sketching.

Taniel made his right hand into a fist. He didn’t want her to see him shaking. “I… not now, Pole.”

She pointed again, more insistently.

Taniel took another deep breath of mala and closed his eyes. He felt tears roll down his cheeks.

He felt her take the book and pencils off his chest. Heard the table move. He expected a reproach. A punch. Something. When he opened his eyes again, he saw her bare feet disappearing up the stairs of the mala den and she was gone. He took another deep breath of mala and wiped the tears off his face.

The room began to fade into the mala haze along with his memories; all the people he’d killed, all the friends he’d see.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...