- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

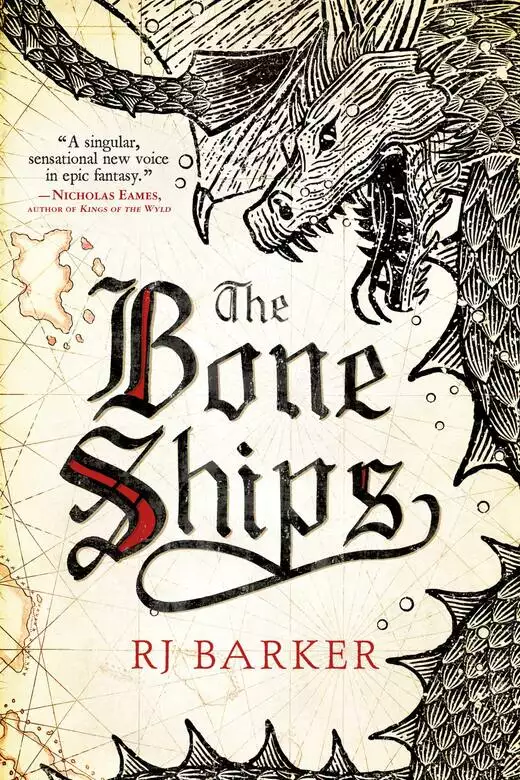

Synopsis

A crew of condemned criminals embark on a suicide mission to hunt the first sea dragon seen in centuries in the first book of this adventure fantasy trilogy.

Violent raids plague the divided isles of the Scattered Archipelago. Fleets constantly battle for dominance and glory, and no commander stands higher among them than "Lucky" Meas Gilbryn.But betrayed and condemned to command a ship of criminals, Meas is forced on suicide mission to hunt the first living sea-dragon in generations. Everyone wants it, but Meas Gilbryn has her own ideas about the great beast.

In the Scattered Archipelago, a dragon's life, like all lives, is bound in blood, death and treachery.

Release date: September 24, 2019

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 512

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Bone Ships

RJ Barker

They are not the sort of words that you expect to start a legend, but they were the first words he ever heard her say.

She said them to him, of course.

It was early. The scent of fish filled his nose and worked its way into his stomach, awakening the burgeoning nausea. His head ached and his hands trembled in a way that would only be stilled by the first cup of shipwine. Then the pain in his mind would fade as the thick liquid slithered down his gullet, warming his throat and guts. After the first cup would come the second, and with that would come the numbness that told him he was on the way to deadening his mind the way his body was dead, or waiting to be. Then there would be a third cup and then a fourth and then a fifth, and the day would be over and he would slip into darkness.

But the black ship in the quiet harbour would still sit at its rope. Its bones would creak as they pulled against the tide. The crew would moan and creak as they drank on its decks, and he would fall into unconsciousness in this old flenser’s hut. Here he was, shipwife in name only. Commander in word only. Failure.

Voices from outside, because even here, in the long-abandoned and ghost-haunted flensing yards there was no real escape from others. Not even the memory of Keyshan’s Rot, the disease of the boneyards, could keep people from cutting through.

“The Shattered Stone came in this morran, said they saw an archeyex over Sleightholme. Said their windtalker fell mad and it nearly wrecked ’em. Had to kill the creature to stop it bringing a wind to throw ’em across a lee shore.”

“Aren’t been an archeyex seen for nigh on my lifetime. It brings nothing good – paint that on a rock for the Sea Hag.” And the voices faded, lost in the hiss of the waves on the beach, eaten up by the sea as everything was destined to be, while he thought on what they said – “brings nothing good”. May as well as say that Skearith’s Eye will rise on the morran, for this is the Hundred Isles – when did good things ever happen here?

The next voice he heard was the challenge. Delivered while he kept his eyes closed against the tides of nausea ebbing and flowing in hot, acidic waves from his stomach.

“Give me your hat.” A voice thick with the sea, a bird-shriek croak of command. The sort of voice you ran to obey, had you scurrying up the rigging to spread the wings of your ship. Maybe, just maybe, on any other day or after a single cup of shipwine, maybe he would have done what she said and handed over his two-tailed shipwife’s hat, which, along with the bright dye in his hair, marked him out as a commander – though an undeserving one.

But in the restless night his sleep had been troubled by thoughts of his father and thoughts of another life, not a better one, not an easier one, but a sober one, one without shame. One in which he did not feel the pull of the Sea Hag’s slimy hands trying to drag him down to his end. One of long days at the wing of a flukeboat, singing of the sea and pulling on the ropes as his father glowed with pride at how well his little fisher boy worked the winds. Of long days before his father’s strong and powerful body was broken as easily as a thin varisk vine, ground to meat between the side of his boat and the pitiless hull of a boneship. His hand reaching up from black water, a bearded face, mouth open as if to call to his boy in his final agonising second. Such strength, and it had meant nothing.

So maybe he had, for once, woken with the idea of how wonderful it would be to have a little pride. And if there had been a day for him to give up the two-tailed hat of shipwife, then it was not this day.

“No,” he said. He had to scrape the words out of his mind, and that was exactly how it felt, like he drew the curve of a curnow blade down the inside of his skull; words falling from his mouth slack as midtide. “I am shipwife of the Tide Child and this is my symbol of command.” He touched the rim of the black two-tailed cap. “I am shipwife, and you will have to take this hat from me.”

How strange it felt to say those words, those fleet words that he knew more from his father’s stories of service than from any real experience. They were good words though, strong words with a history, and they felt right in his mouth. If he were to die then they were not bad final words for his father to hear from his place, deep below the sea, standing warm and welcome at the Hag’s eternal bonefire.

He squinted at the figure before him. Thoughts fought in his aching head: which one of them had come for him? Since he’d become shipwife he knew a challenge must come. He commanded angry women and men, bad women and men, cruel women and men – and it had only ever been a matter of time before one of his crew wanted the hat and the colours. Was it Barlay who stood in the door hole of the bothy? She was a hard one, violent. But no, too small for her and the silhouette of this figure wore its hair long, not cut to the skull. Kanvey then? He was a man jealous of everything and everyone, and quick with his knife. But no, the silhouette appeared female, undoubtably so. No straight lines to her under the tight fishskin and feather. Cwell then? She would make a move, and she could swim so would have been able to get off the ship.

He levered himself up, feeling the still unfamiliar tug of the curnow at his hip.

“We fight then,” said the figure and she turned, walking out into the sun. Her hair worn long, grey and streaked in the colours of command: bright reds and blues. The sun scattered off the fishskin of her clothing, tightly wound about her muscled body and held in place with straps. Hanging from the straps were knives, small crossbows and a twisting shining jingling assortment of good-luck trinkets that spoke of a lifetime of service and violence. Around her shoulders hung a precious feathered cloak, and where the fishskin scattered the sunlight the feather cloak hoarded it, twinkling and sparkling, passing motes of light from plume to plume so each and every colour shone and shouted out its hue.

I am going to die, he thought.

She idled away from the slanted bothy he had slept in, away from the small and stinking abandoned dock, and he followed. No one was around. He had chosen this place for its relative solitude, amazed at how easily that could be found; even on an isle as busy as Shipshulme people tended to flock together, to find each other, and of course they shunned such Hag-haunted places as this, where the keyshan’s curse still slept.

Along the shingle beach they walked: her striding, looking for a place, and him following like a lost kuwai, one of the flightless birds they bred for meat, looking for a flock to join. Though of course there was no flock for a man like him, only the surety of the death he walked towards.

She stood with her back to him as though he were not worth her attention. She tested the beach beneath her feet, pushing at the shingle with the toes of her high boots, as if searching for something under the stones that may rear up and bite her. He was reminded of himself as a child, checking the sand for jullwyrms before playing alone with a group of imaginary friends. Ever the outsider. Ach, he should have known it would come to this.

When she turned, he recognised her, knew her. Not socially, not through any action he had fought as he had fought none. But he knew her face – the pointed nose, the sharp cheekbones, the weathered skin, the black patterns drawn around her eyes and the scintillating golds and greens on her cheeks that marked her as someone of note. He recognised her, had seen her walking before prisoners. Seen her walking before children won from raids on the Gaunt Islands, children to be made ready for the Thirteenbern’s priest’s thirsty blades, children to be sent to the Hag or to ride the bones of a ship as corpselights – merry colours that told of the ship’s health. Seen her standing on the prow of her ship, Arakeesian Dread, named for the sea dragons that provided the bones for the ships and had once been cut apart on the warm beach below them. Named for the sea dragons that no longer came. Named for the sea dragons that were sinking into myth the way a body would eventually sink to the sea floor.

But oh that ship!

He’d seen that too.

Last of the great five-ribbers he was, Arakeesian Dread. Eighteen bright corpselights dancing above him, a huge long-beaked arakeesian skull as long as a two-ribber crowned his prow, blank eyeholes staring out, his beak covered in metal to use as a ram. Twenty huge gallowbows on each side of the maindeck and many more standard bows below in the underdeck. A crew of over four hundred that polished and shone every bone that made his frame, so he was blinding white against the sea.

He’d seen her training her crew, and he’d seen her fight. At a dock, over a matter of honour when someone mentioned the circumstances of her birth. It was not a long fight, and when asked for mercy, well, she showed none, and he did not think it was in her for she was Hundred Isles and fleet to the core. Cruel and hard.

What light there was in the sky darkened as if Skearith the godbird closed its eye to his fate, the fierce heat of the air fleeing as did that small amount of hope that had been in his breast – that single fluttering possibility that he could survive. He was about to fight Meas Gilbryn, “Lucky” Meas, the most decorated, the bravest, the fiercest shipwife the Hundred Isles had ever seen.

He was going to die.

But why would Lucky Meas want his hat? Even as he prepared himself for death he could not stop his mind working. She could have any command she wanted. The only reason she would want his would be if…

And that was unthinkable.

Impossible.

Meas Gilbryn condemned to the black ships? Condemned to die? Sooner see an island get up and walk than that happen.

Had she been sent to kill him?

Maybe. There were those to whom his continued living was an insult. Maybe they had become bored with waiting?

“What is your name?” She croaked the words, like something hungry for carrion.

He tried to speak, found his mouth dry and not merely from last night’s drink. Fear. Though he had walked with it as a companion for six months it made it no less palatable.

He swallowed, licked his lips. “My name is Joron. Joron Twiner.”

“Don’t know it,” she said, dismissive, uninterested. “Not seen it written in the rolls of honour, not heard it in any reports of action.”

“I never served before I was sent to the black ships,” he said. She drew her straightsword. “I was a fisher once.” Did he see a flash in her eyes, and if he did what could it mean? Annoyance, boredom?

“And?” she said, taking a practice swing with her heavy blade, contemptuous of him, barely even watching him. “How does a fisher get condemned to a ship of the dead? Never mind become a shipwife.” Another practice slash at the innocent air before her.

“I killed a man.”

She stared at him.

“In combat,” he added, and he had to swallow again, forcing a hard ball of cold-stone fear down his neck.

“So you can fight.” Her blade came up to ready. Light flashed down its length. Something was inscribed on it, no cheap slag-iron curnow like his own.

“He was drunk and I was lucky,” he said.

“Well, Joron Twiner, I am neither, despite my name,” she said, eyes grey and cold. “Let’s get this over with, ey?”

He drew his curnow and went straight into a lunge. No warning, no niceties. He was not a fool and he was not soft. You did not live long in the Hundred Isles if you were soft. His only chance of beating Lucky Meas lay in surprising her. His blade leaped out, a single straight thrust for the gut. A simple, concise move he had practised so many times in his life – for every woman and man of the Hundred Isles dreams of being in the fleet and using his sword to protect the islands’ children. It was a perfect move he made, untouched by his exhaustion and unsullied by a body palsied with lack of drink.

She knocked his blade aside with a small movement of her wrist, and the weighted end of the curving curnow blade dragged his sword outward, past her side. He stumbled forward, suddenly off balance. Her free hand came round, and he caught the shine of a stone ring on her knuckles, knew she wore a rockfist in the moment before it made contact with his temple.

He was on the ground. Looking up into the canopy of the wide and bright blue sky wondering where the clouds had gone. Waiting for the thrust that would finish him.

Her sword tip appeared in his line of sight.

Touched the skin of his forehead.

Raked a painful line up to his hair and pushed the hat from his head and she used the tip of her sword to flick his hat into the air and caught it, putting it on. She did not smile, showed no sense of triumph, only stared at him while the blood ran down his face and he waited for the end.

“Never lunge with a curnow, Joron Twiner,” she said quietly. “Did they teach you nothing? You slash with it. It is all it is fit for.”

“What poor final words for me,” he said. “To die with another’s advice in my ear.” Did something cross her face at that, some deeply buried remembrance of what it was to laugh? Or did she simply pity him?

“Why did they make you shipwife?” she said. “You plain did not win rank in a fight.”

“I—” he began.

“There are two types of ship of the dead.” She leaned forward, the tip of her sword dancing before his face. “There is the type the crew run, with a weak shipwife who lets them drink themselves to death at the staystone. And there is the type a strong shipwife runs that raises his wings for trouble and lets his women and men die well.” He could not take his eyes from the tip of the blade, Lucky Meas a blur behind the weapon. “It seems to me the Tide Child has been the first, but now you will lead me to him and he will try what it is to be the second.”

Joron opened his mouth to tell her she was wrong about him and his ship, but he did not, because she was not.

“Get up, Joron Twiner,” she said. “You’ll not die today on this hot and long-blooded shingle. You’ll live to spend your blood in service to the Hundred Isles along with every other on that ship. Now come, we have work to do.” She turned, sheathing her sword, as sure he would do as she asked as she was Skearith’s Eye would rise in the morning and set at night.

The shingle moved beneath him as he rose, and something stirred within him. Anger at this woman who had taken his command from him. Who had called him weak and treated him with such contempt. She was just like every other who was lucky enough to be born whole of body and of the strong. Sure of their place, blessed by the Sea Hag, the Maiden and the Mother and ready to trample any other before them to get what they wanted. The criminal crew of Tide Child, he understood them at least. They were rough, fierce and had lived with no choice but to watch out for themselves. But her and her kind? They trampled others for joy.

She had taken his hat of command from him, and though he had never wanted it before, it had suddenly come to mean something. Her theft had awoken something in him.

He intended to get it back.

From the hill above Keyshanblood Bay Joron could see his ship – her ship – Tide Child. The ship lay held by the staystone and, as befitting a ship of the dead, his bones had been painted black and no corpselights danced above him. His wings, which had been clumsily furled atop the wingspines jutting from the grey slate of the decks, were also black. Every inch of the ship should have been black, but the ship’s crew and his shipwife – and he – had been slack in their care and it looked as if a gentle rain of ash had fallen over the ship, dotting him with specks of white where the bone showed through. His prow was the slanted and the smooth hipbones of a small arakeesian, a long-dead sea dragon, angled to cut through the water. At the waterline the beak of the keyshan skull poked out from the hipbones, and curving back from it were the ribs, four long bones that ran the length of the ship and helped him slide through the water. Above the ribs were the bones of the ship that made his sides, and these were sharp and serrated, a riot of odd angles and spiked bone meant to repel borders, the shearing edges and prongs making him hard to climb.

Tide Child’s colour showed he was a last-chance ship, the crew condemned to death. The only chance anyone had for a return to life was through some heroic act, something so un-deniably great that the acclaim of the people would see their crimes expunged and their life restored to them. Such hope made desperate deckchilder, and desperate deckchilder were fierce. Though if any forgiveness had ever been offered to the dead it had not been in Joron’s lifetime, nor in his father’s lifetime before him.

He should have been a terror, cutting his way through the seas of the Scattered Archipelago, but instead of roaring through the grey seas Tide Child sat at the staystone, weed waving lazily around him from where it had grown on the slip bones of his underside, the water about the black ship greasy with human filth: sewage, rotting food and the other hundreds of bits of flotsam a ship constantly generated. Across the spars of the wingspines sat skeers, lean white birds no more than dots from this distance, but he knew their red eyes and razored bills, always hungry.

“Mark of a lax ship,” whispered Meas from beside him.

“What?”

“The skeers. If a deckchild falls asleep they’ll have out an eye or a tongue – seen it more than once. Should have someone with a sling out there. Mind you, you don’t have to see the birds to know that ship’s not loved as it should be; you can smell it.”

He sniffed at the air. Even up here on the hill he could smell his ship, like a fish dock at the slack of Skearith’s Eye when the heat burned down from above and there was no shadow, no shelter, no release.

“Tide Child,” he said.

“A weak name,” she replied and strode off, vanishing into the foliage which grew strong and thick away from the old flensing yard. Her dark body disappeared among the riot of bright purple gion leaves, thick spreading fans providing respite from the slowly climbing eye of Skearith. Twined around them was bright pink varisk, vines as thick and strong as a woman’s thighs, leaves almost as big as the gion, fighting it for the light.

Resentment was his companion through the forest, not just because she made him struggle through the foliage, rather than taking the longer, clearer path kept by the villagers. It was also for the ship, for his command. In the six months since he had been condemned the ship had filled his life; thoughts of riding it to glory or escaping it completely had trapped him in a current of indecision. The ship may not have been much, but it had been his, and when she insulted it she insulted him. Hag’s curse on you, Lucky Meas. He had no doubt she would turn out to be anything but lucky for him, for the ship or for those aboard, though in truth he cared far less about them, keyshans take them. He stumbled after her, mouth dry, body aching for the gourd at his hip, shaking for it, but the one time he paused to unlimber it and take a drink she had stopped and turned.

“We’ll find water in the gion forest,” she said, “or we’ll tap a varisk stalk. My officers aren’t soaks.”

Her officers? What did she mean by that? And he added another item to a growing list of resentments in his head.

The huge gion and varisk plants were at their height now; any paths there may have been through this part of the forest had been quickly overgrown by bright creepers, and their sickly colours made his head ache even more. The plants fell easily to his curnow and a creeping sense of claustrophobia grew within him, a feeling of being trapped that joined the crew of his discomforts as he felt the path behind them close up, overtaken by the relentless growth of vines and stalk and leaf. The forest birds raised a cacophony at the clack of blade on stalk, some calling warnings, some singing out threats, and his knuckles whitened on the hilt of his swinging blade. This was the time of year when most were lost to firash, the giant birds darting out in ambush, opening guts with their claws and dragging their dying prey away to eat alive. He wondered if Lucky Meas would fall to one. But no, somewhere inside he knew Lucky Meas was not destined to die in a forest at the claws of a great bird.

Joron was so lost in his thoughts he barely heard Meas when next she spoke.

“Is your crew on board?”

He stumbled over a thick root pulsing with blue sap.

“All except the windtalker.”

She stopped, turned and stared at him. “Black ships do not have windtalkers.”

“Ours does, but the crew won’t have it aboard when the ship is still – say it’s bad luck.”

She looked at him as if wanting more, but he could not think why – surely everyone knew this? Just the thought of the gullaime made his flesh creep over and above the shaking and nausea wracking him for want of drink.

“Where is it then?”

“Where?”

“I’ll not ask again. Are you so cracked in the head by drink that you cannot answer a simple question?”

He could not meet her eye.

“On the bell buoy off the bay entrance. We cast it there.”

“And the last time it touched land? The last time it was brought to a windspire?”

“I…” His head refused to clear; the world swam before him in a thousand bright colours that twisted like his aching guts.

“Northstorm’s whispered curses, man, have the drink you long for and pray to the Sea Hag it brings you sense if not sobriety. I’ll ask the windtalker myself when it comes on board.” And she turned away, stalking through the bright forest. He brought the flask to his mouth, taking a gulp of the thick soupy alcohol. Something hidden by the gion and varisk around him screamed out its last moment as nature played out the endless game of prey and predator.

The nearer they came to the beach the stronger the smell of the ship became. He had never noticed it on his return before, never thought about it, but today it was nauseating. It was not the smell of death that drifted across the bay from the black ship, but the stink of life – carefree, chaotic and unconcerned. They had found this quiet bay where orders were unlikely to reach them a month ago and tied up the ship. The fisher village in the bay wanted nothing to do with the crew so Joron had felt it safe to leave. The very few among Tide Child’s crew who could swim were not enough to be a threat to the hard women and men there. His tumbledown bothy was far enough away that the deformed land hid the ship from him, and he wondered what it said about him that he had chosen somewhere where he could not even see his command?

Nothing good.

The flukeboat lay where he had left it, askew on the pale pink beach. The sand looked attractive, relaxing, but each grain was a lie as it was a beach of trussick shells. Most were smashed but in among them were plenty of whole ones that would shatter under a foot and cut the sole open, so as they walked over the beach he had to pick his way carefully forward while Meas, booted Lucky Meas, strode confidently on.

The flukeboat resembled a cocoon. Built from gion leaves which had been dried and treated until they became soft and pliable like birdleather, then wrapped around a skeleton of fire-hardened varisk stalks and the whole thing baked in the sun until it was bone hard. Flukeboats were brown to start with, until their owners painted them in lurid colours: symbols of the Sea Hag, Maiden or Mother, eyes of the storms or the whispers of the four winds. This flukeboat was little more than a rowboat, big enough for ten but light enough for one to row if they must. Flukeboats ranged as large as to hold twenty and sometimes thirty and more crew, with large gion leaves, dried and treated to act as wings, catching the wind above and powering the boats through the sea.

Vessels for the foolishly brave, most said, as they were brittle, not like the hard-hulled boneships. A flukeboat could be wrecked by one good gallowbow shot. But Joron knew they had advantages too, those brittle boats; he had grown up helping his father on one, just the two of them against the sea in a boat bright blue and named the Sighing East, for the storm that loved a deckchild. It had been fast, able to outrun almost anything, even the crisk and the vareen, and when those great beasts of the sea raised their heads looking for prey they had never caught the Sighing East. The little boat had run with the wind, salt spray stiffening Joron’s hair as he stood in the prow, laughing at the danger, sure in the knowledge his father would steer them safe. He always steered them safe, always found the fish, always protected his singing boy. Until the last day, and then he could not. Sometimes it was hard to believe that had been Joron’s life, that just months ago he had been that scarless, careless, laughing boy in the prow of a flukeboat.

How had it come to this?

How had he ended here?

Nineteen years on the sea and condemned to die. The world pulsed, the blue sky darkening at the edges.

He knew these thoughts as offspring of the drink, the melancholy it brought he had only ever been able to drink through, running toward oblivion to escape himself. But he could not drink now. Not in front of her. He would keep going even if just to spite her. If she put him to cleaning filth from the bilges he would do it, biding his time, waiting for his moment.

Meas reached the flukeboat, pulling it upright so the thin keel cut into the sand and she could slide it into the lapping water. No happy colours for this boat; it was unnamed, painted black and given only the one eye on its beak to guide it through the sea. She went to the front, one foot in the hull, one raised on the beak, looking every inch the shipwife. She did not look back, did not speak, did not need to. He knew what was required.

He was crew now.

She stood where he should have, though never had; no member of Tide Child’s crew would ever have rowed him anywhere, would have laughed if he had asked. By the time he had picked his way across the sharp beach the boat had drifted out into the still bay and he had to wade out to it, the salt water stinging a hundred tiny cuts on the bottoms of his feet. He pulled himself, dripping, into the boat, feeling the wetness as humiliation while the growing heat burned the moisture from his clothes. He picked up the two oars and set them in their notches.

“Foolish to leave the boat here,” she said.

“Who would steal a boat fit only for the dead?”

“The dead,” she said and pointed at Tide Child, far ahead of them and thick in the water. The ship was not dipping or moving with the motion of the sea, it looked as steady and immovable as a rock, a rock to wreck a soul upon.

“I brought it to the shore so they could not have it.” He said the words, though he wanted to shout at her. Could she really not know the crew would use the boat to run if he left it with them?

“Well, unless they are an uncommon lot, I reckon at least a few of ’em can swim?” She did not look round to see if he acknowledged what she said, did not need to as they both knew she was right. The only reason the boat was still there was probably because the crew of Tide Child were so drunk they had not thought it through any more than he had. Again the damp clothes against his skin felt like shame. “And it may have passed your notice” – she pointed at Tide Child – “but they already have a ship.” He stared at her, feeling like the fool he was. “Row then,” she said, impatient, not looking back. “I would see what poor sort of crew a poor man like you is shipwife to.”

Warm, damp clothes against his skin.

Black water, they called it, that greasy area where the detritus of a ship held the water that little tighter to it, a disturbance that caused a circular calm about the vessel. And this water was black in more than name. The reflected hull of Tide Child made rowing into the black water to approach an abyssal hole, like the places where the floor of the sea fell away beneath a ship and a deckchild heard the Sea Hag’s call to join her in the depths. One moment Joron rowed through limpid green sea where the pink sand gently shoaled away beneath them, and then they were in the cold shadow of the ship, rowing through darkness towards darkness: life into death.

There were rules in the Hundred Isles navy for a shipwife’s approach: calls to be made, horns to be blown, clothes to be worn and salutes to be offered. Lucky Meas – perched on the beak of the flukeboat – received none of this; not even the careless courtesy of a ladder thrown over the ship’s side greeted her. And though she said nothing, Joron could feel the affront radiating from every taut muscle of her body. When the flukeboat was within a span of Tide Child she leaped from the beak of the boat, the sudden change in weight as she jumped pushing it down into the black water, buoyancy pushing it back up in a fountain of white foam that tried, and failed, to follow Meas Gilbryn up the side of the ship. Where the water fell back, disturbing the bits of food and rotting rubbish, sending them bobbing away from the smooth black ribs of the hull, Meas seemed to defy gravity. She needed no ladder; the ship became her steps, each spike and sharp edge, each piece of the ve

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...