- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

The sea dragons are returning, and Joron Twiner's dreams of freedom lie shattered. His Shipwife is gone and all he has left is revenge.

Leading the black fleet from the deck of Tide Child Joron takes every opportunity to strike at his enemies, but he knows his time is limited. His fleet is shrinking and the Keyshan's Rot is running through his body. He runs from a prophecy that says he and the avian sorcerer, the Windseer, will end the entire world.

But the sea dragons have begun to return, and if you can have one miracle, who is to say that there cannot be another?

'Excellent . . . one of the most interesting and original fantasy worlds I've seen in years'

Adrian Tchaikovsky

Release date: September 28, 2021

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 592

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

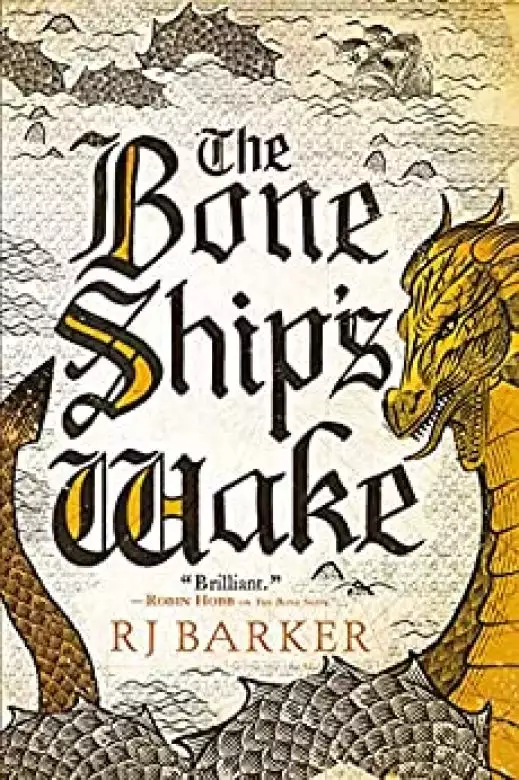

The Bone Ship's Wake

RJ Barker

“And how do you raise the sea dragons, Meas Gilbryn?”

As the waves withdraw, the tempest eases, the agony flows away and leaves behind a thousand other little pains. Her wrists and ankles, where the ropes hold her on the chair, the skin rubbed raw by straining against twisted cords. The gnaw of hunger in her belly, the rasp in her throat from screaming, the ache in her feet from toes broken and never reset correctly. The sharp catch of the clothes on her back against the scars left by the whipping cord.

The throb of a tooth in the back of her mouth going bad, one they are yet to notice. She takes a little comfort in that. That one little pain is hers, one little pain they could exploit but have not. Not yet. One day they will, no doubt about that. They are as fastidious in her pain as they are in their care of her. But today it is a small victory that she will claim over her tormentor.

“I do not know how to raise a sea dragon.”

A sigh. Meas opens her eyes to see the hagpriest sat before her on a stool. She is beautiful, this girl. Her brown eyes clear, dark skin unblemished and shining in the light coming through the barred window. Her white robe remains – miraculously, given her profession – free of blood or stain as she places the glowing iron back in the brazier. Meas smells her own flesh burning. It makes her mouth water with hunger, even as the pain from the burns sears across her nerves.

They burn her on the back of the calf. It is as if they do not want their cruel work to be immediately apparent.

“This could all stop, Meas, you only have to tell the truth.”

She has been telling them the truth for weeks, but they do not believe her. So she starts in the same place. The same place they always start.

“My title is shipwife. And if my mother wants my secrets, then tell her to come and ask for them.”

Laughter at that. Always laughter.

“You are not important enough to bring powerful people down here,” says her torturer. She stands, walks to the back of the small, clean white room and opens a cupboard. “You should know I am the very least of my order, the most inconsequential of novices. I am all you are deemed worth, I am afraid.” She takes a moment, staring at the shelves, choosing from the instruments stored there. Eventually settling on a roll of variskcloth which shifts in her arms and clinks with the sound of tools hidden within. Meas’s heart starts to beat faster as the hagpriest returns to sit opposite her.

“I know I am important,” says Meas, sweat starts on her brow, “and I know my mother comes down, for I hear you talking outside the room to her. I hear you, no matter how low you keep your voices.” She was so sure.

The hagpriest smiles and places the roll of variskcloth on a small table by the brazier.

“I am sorry to disappoint you, Shipwife Meas, but that is simply another of my order. I am told your mother has never so much as mentioned coming down here.” She stares at Meas. “Or mentioned you.”

Something small but important breaks within her at that. She has been so sure. But in the hagpriest’s words is the ring of truth.

“Now, Shipwife Meas, let us look to your hands.” The hagpriest’s hands are gentle when they touch her, soft, so unlike Meas’s own, hardened by years at sea. But they are also strong as she forces Meas to uncurl her fingers from the fists she has balled them into. “The nails have grown back remarkably well,” says the hagpriest. “Sometimes, after they have been ripped from the nail bed, they grow back malformed, or not at all. But you are strong.” She lets go of Meas’s hand and turns to her table, unrolls the variskcloth to reveal the tools within. Sets of pliers of various sizes with strange jaws and beaks, although Meas is far more familiar with them than she had ever wished to be. The hagpriest picks over them, first taking one out and inspecting it, then another. “It is sad for you, that you hold such an important secret. And sad for me also, I suppose. I must be careful with you, oh so careful, and we must take our time. Were your secrets less important, our relationship would be far more agreeable.” She clacks a pair of pliers together in front of Meas’s face.

Open. Shut.

Open. Shut.

“By which I mean short, for you, Shipwife. Oh, agonising, indeed, far more agonising than anything I have yet put you through. But you would thank me when I brought out the knife that would send you to the Hag, if that is your fate.” She puts the pliers back. Takes out another, smaller pair.

Open. Shut.

Open. Shut.

She turns to Meas. “They often do thank me, you know. Women and men have so many secrets, and they become a burden. I allow them release from their burdens. And I allow the pain to end.” She forces Meas’s hand open again and places the pliers around the end of the nail on Meas’s longest finger. A gradually rising pressure in the nail bed. “They cry, Meas. They thank me and they cry with joy when I end them.” More pressure; not pain, not yet. Just the promise of it. “Now, tell me, how do you raise the arakeesians, Meas Gilbryn?”

Meas stares into the eyes of her torturer, finds no pity there. Worse, she is sure what the torturer believes she feels for Meas is compassion. That she thinks she is a woman doing an important job, no matter how unpleasant it may be. And she really, genuinely, pities Meas. That she thinks it a shame that Meas’s end could not be quick, if agonising. The pressure and the pain in her nail builds and builds. And she knows, as she has known so many times before, that she can bear it no longer.

“I cannot raise keyshans.” Words like shame, burning her throat as if poisonous. Bringing tears and choking sobs with them. “It is my deckkeeper, Joron Twiner. The gullaime name him Caller and he sings the keyshans up from their sleep.”

The hagpriest staring into her eyes.

“The same lies, Meas, they do not become more truthful just because you repeat them. But I admire your strength. We will find your deckkeeper, do not worry, and I will speak with him.” Meas steels herself, ready for the rip and the agony. Instead the pressure falls away. “I think, sweet Meas,” says the hagpriest, and she strokes her cheek, “that we are done for today. You are tired, and you need to rest. Think about today, and what may come in our future. Think about secrets and what you can share to end your pain.” She rolls up her tools, walks over to the cupboard and replaces the roll. “I will have the seaguard come, take you back to your rooms. I have had a bath drawn for you.” She turns, walks back to Meas and then she changes, from gentle to hard. Grabs Meas’s face, pushes her head back so she looks up at the hagpriest through tears of shame. “You are a handsome woman, you know? You are very fine looking.” She leans in close. “I am hoping,” she whispers, “that if I ask nicely enough, they will let me take one of your eyes.”

The hagpriest lets go, walks away, leaving Meas alone with two opposite thoughts warring in her mind:

Joron, where are you? You said you would come, and Joron, stay away. Whatever you do, you must not let them take you.

Skearith’s Blind Eye had closed and Deckkeeper Deere walked through night as thick and black as congealed blood. The gentle hiss of the sea on the shore like the drawing of breath, in and out and out and in. The crunch of shingle under her boots as she walked toward the lookout tower. Up the ladder on the stone pier, along the walkway of stout varisk, cured and black with age. The wind touched her face, cooling for now, not long until it became the biting cold of the sleeping season when ice would coat everything in Windhearth and the boneships would come in, heavy with ice as white as their hulls, seeking new supplies before they resumed their patrols of the northern waters. Not as numerous now those boneships, not calling as often. The sea was more dangerous than it ever had been; keyshans roamed, keyshans and much worse out there on the water.

Touching the hilt of the straightsword on her hip for reassurance.

“Bern keep me safe,” said under her breath before starting the climb up the ladder to the tower – the rungs cold enough to numb her hands.

“D’keeper.”

“Seen anything, Tafin?” The man shook his head, his body crouched, encased in thick robes against the night chill.

“S’quiet.”

Wind against her face.

“The breeze seems to be picking up,” she said. “I feel it when I turn to the sea.” Saw the screwing up of the deckchild’s face, knew it for disagreement. One of those many hundreds of little ways the old hands told you that you had said something wrong or foolish. “What is it, Tafin?” She waited for the man’s gentle instruction. She liked him, he never made her feel stupid.

“Winds is always off the land at this time, see. You…” His voice fell away.

A darkness against the darkness. A shape detaching from the night. A ship on the water, but no glowing corpselights dancing above it. No honesty in its approach. A black ship, coming in fast on the winds of a gullaime, and before she could open her mouth the call was going up from Tafin, and the deckchild on the tower opposite. Panic in their voices.

“Black ship rising!”

“… ship rising!”

And she was already halfway down the tower, sliding down the rungs. In the town and on the docks alarm bells were ringing and she knew every woman and man would be pulling on clothes, reaching for weapons.

Feeling fear.

Her feet hit the stone pier and she stumbled as she heard the warmoan, the sound of wind over the taut cords of the gallowbows, loud in her ear. The familiar sound of loosing, the high elastic twang of the cord, the thud of the bow arms coming forward, the hiss of the wingbolt. A moment later the sound of varisk and gion smashing and the screams of deckchilder, as the towers were hit by heavy stone. Too dark to see the far tower but she heard the groan and crack of the varisk structure as it toppled, the huge splash as it hit the water. Knew it lost. Then she was throwing herself to the floor as she heard the tower behind her coming down. Rolling over, as if the massive, crushing weight coming toward her should be met head-on. As if she needed to face her death bravely, but at the last moment she brought her hands up – a natural reaction, though what use she thought her slender arms would be to ward off the jointweight of that broken mass of gion and varisk spars, she did not know.

At the last she screamed.

Felt shame.

Felt shock.

Horror as Tafin landed by her, his head broken, body pierced by spars. Smelling like a butcher’s row.

But she lived.

Had the Hag smiled on her today? Not so much as a cut on her and the lookout tower had fallen neatly around her. She rolled over. Stared into the harbour as the black ship cruised past. The crew throwing lamps over the side. At first, she thought of it as light for the archers in the rigging but it was not. No arrow or crossbow bolt pierced her flesh, she was either not seen or not cared about. No, these lights were not to find her, they were so people like her could see this ship. Could see the cruel keyshan beak that crowned the front of him. Could see the spikes and burrs. See the skulls that topped the bonerails along the side, and under the brightest lamps could see the name. The most feared name in the Hundred Isles, and the most wanted.

Tide Child.

As the ship passed she saw its crew, saw the deckchilder arrayed for war, crying out for blood and plunder, saw Tide Child’s seaguard, stood like statues in clothes as black as the ship. Saw the gullaime, dressed brightly in thick robes and surrounded by six of its own in ghostly white. Saw the command crew on the rump. The burned woman, the massive forms of Hag-cursed Muffaz and Barlay Oarturner. Between them all, he stood. Stock-still and swathed in rags, even his face covered, all hidden apart from his eyes. Did he turn as the ship passed? Did he see her on the ground? Did he watch her as he glided into the harbour? A shiver of fear went through her, for no woman or man was more of a danger to the Hundred Isles fleet than that one.

The Black Pirate had come to Windhearth.

And where the Black Pirate went, death and fire followed.

She heard his voice, loud, but fragile, like the croaking of a skeer.

“Bring him to landward. All bows at the ready. Put fire to my bolts, my girls and boys, and fire ’em well.”

With that order she knew her one hope – that Maiden’s Loss, the two-ribber moored at the harbour might save them – was gone. Oh, Tide Child might be a pirate right enough, but they flew him well, manoeuvred him sharp and fleet as any ship. He came about, pulling side-on to Maiden’s Loss. Her ears hurt as the gullaime brought their power to bear to slow the ship.

Fire streaking through the night as Tide Child loosed its great bows and its underdeck bows in one devastating volley into the smaller ship. All was fire then. No more need for lamps. Boats let down from Tide Child, and more black ships coming through the harbour mouth. A grappling hook chinked against the stone of the pier as a smaller black ship came to a stop and then Deere was up, running for the town as fast as she could. She was hurt, not bleeding but bruised. Forced to run at a limp. Aware that behind her more grappling hooks would be coming. The ship would be pulled up next to the pier. Pirates would swarm ashore.

How quickly the world changed. A few minutes ago it was as cold and crisp and dull as every other night. Now it was a nightmare, firelight turning her world into a crackling, screaming landscape of jumping shadows.

The sound of feet. People running. Hers or theirs? She threw herself between two buildings as a group of deckchilder ran past. Hers? Or theirs? She did not know. She ran for the main square, where any defences would be found. Had Shipwife Halda been on Maiden’s Loss? She hoped not, for Shipwife Halda was the only officer on the island with any experience of war; if defence was left to Shipwife Griffa, who had never commanded anything more fleet than a loading crane, they were lost already.

Running. Running. Running.

Into the square, fighting everywhere. If there had been order it was lost. Bodies on the ground, peppered with crossbow bolts. Almost getting tangled up in her own sword as she drew it. Striking out at the vague shapes around her. Aware she did not know who they were. Hers or theirs? Breathing hard, frightened. She did not know. Too frightened to care.

Strike. Cut. Blood. Scream. Shout.

She wanted to live. It was all she cared about. In among the heaving bodies. The running bodies. The panicked women and men. She wanted to live.

Found herself in a space. Fire from the burning ship painting the buildings orange, changing their shape, making everything alien. Strange, screaming, fierce faces looming out of the night. She slashed at a figure. Felt resistance as her blade was met. Staggered back. Face to face with a small woman, pinch-faced, mean eyes.

“Come to Cwell, lass,” said the woman.

The fear was liquid within her. This was the Black Pirate’s shadow. Deere lunged. The shadow parried, twisted her blade, pulled it from her hand; then, with a hard push, sent her sprawling back onto the dirt.

“Don’t kill me!” Those frail arms of hers coming up once more.

“Officer is it?” said the shadow.

“Deckkeeper,” and she cursed herself for stuttering with fear over her rank.

“Well, he’ll want to speak to you then.” And the shadow swung the weighted end of her curnow and all was darkness.

Waking. Tasting blood in her mouth. The warmth of Skearith’s Eye on her face. The sound of skeers on the air. The sound of women and men on the ground. Crying and begging and laughing. The burn of ropes around her wrists and ankles. She opened her eyes. Lying on her side above the beach. Black ships filling the harbour. Lines of women, men and children kneeling on the beach. All tied.

She tried to move. Groaned.

“Another one awake.” A voice from behind her.

“Bring her along then, quicker it’s over with quicker we can leave. I heard Brekir saying fleet boneships were near.” A sudden spike of hope in her chest. She rolled over. Saw the gallows. Four bodies hanging from it. A fifth, Shipwife Griffa she was sure, stood atop a barrel with a rope around her neck. The Black Pirate before her. He took a step back, raised his bone spur foot and kicked the barrel away. Shipwife Griffa fell, her drop abruptly stopped by the rope and she swung like a pendulum as the noose tightened, her legs kicking as she gasped for air. Then Deere was picked up, the rope between her ankles cut and her legs almost gave way beneath her. But the deckchilder did not care. They dragged her along the dock, past the jeering crews of the black ships. At the end she managed to find her feet, to stand as they threw a rope over the cross bar of the makeshift gallows. Placed the noose around her neck. Placed a barrel and lifted her onto it. Pulled on the rope until she had to balance on tip-toe to breathe.

Only then did the Black Pirate approach.

He was well named. Not only was what skin she could see dark, but his clothes also. Black boots, black trews, black tunic and coat. Black scarf swathed around his face so only his eyes showed. Eyes full of darkness.

“What is your name and rank?” he said. The voice, when speaking, surprisingly musical.

“Vara Deere. I am deckkeeper of the Maiden’s Loss.”

“Well, Vara Deere,” he said. “I am afraid your ship is gone and your rank is meaningless to me.”

“You hide your face,” she said, finding the imminence of death made her braver than she had ever thought she could be. “Is it because you are ashamed of what you are? Ashamed that you betray the Hundred Isles? Kill its good people and loyal crews?”

He stared, brown eyes appraising her.

“I cover my face for my own reasons, and it is not shame,” he said, and it surprised her, as she had not expected an answer. “And as for betrayal, that is all the Hundred Isles have ever shown me, do you wonder that I pay it back?”

“You were an officer,” she said, and when he replied there was venom there.

“I was a condemned man, Vara Deere, never anything else. I was sent to die and in death found purpose.” He stepped closer. He smelled wrong, overly sweet, like he had bathed in some sickly unguent. “Now, I have answered your question. Will you answer mine?” He did not wait for a reply, only hissed words at her. “Where is she?”

“Who?”

“Shipwife Meas Gilbryn, Lucky Meas, the witch of Keelhulme Sounding. I know Thirteenbern Gilbryn has her, where is she?”

“I…” She wondered if he was mad, that he expected some lowly deckkeeper from a poorly kept-up two-ribber at the rump end of the Hundred Isles to know such things. “I do not know.”

He stepped back and she braced herself. But he was not finished.

“Will you serve me, Vara Deere? I have all the officers I need,” he said. “But I always need deckchilder.”

She stared at him, and found, in those deep brown eyes, something that she did not understand. Almost as if he were imploring her to say yes. To join him in the pillaging and destruction of the Hundred Isles that the Black Pirate had indulged in for the last year, that had set every boneship they had searching for him to end his reign of terror.

She stood a little straighter on the barrel.

“They will find you, and you will hang, then,” she said. “So to join you is only to postpone my death a little.” She put her shoulders back. Made her voice as loud as she could. “You and your deckchilder are murderous animals. And I am fleet. I will not join you.” He stared at her. Nodded.

“Well,” he said. “I expect you are right enough about death, Deckkeeper Deere. And I admire your loyalty. I will toast gladly with you at the Hag’s bonefire.” Then he kicked away the barrel and the rope bit and all she was became concentrated on one thing, a desperate need for air.

Then darkness.

All was darkness.

He had thought to meet in the largest bothy in Windhearth, an old building, held together as much by vines as by clever stonework. But in the end he had decided it better to meet in the familiar confines of Tide Child’s great cabin. Above he heard the thud of feet on the deck as his officers – Farys his deckholder, Barlay his oarturner, Jennil, called his second – shouted orders and the ship went about its business. By him stood Aelerin his courser and behind him stood Cwell, his shadow. Few looked upon her without some worry, for she was a woman who radiated violence, and enjoyed and gloried in it.

But she was not alone in that. Shipwife Coult of the Sharp Sither raided with great joy, as did Turrimore of the Bloodskeer and Adrantchi of Beakwyrm’s Glee, and Twiner made no attempt to hold them back. Other, less severe shipwives also joined him: Brekir of the Snarltooth stood at his side, always loyal, and Chiver of the Last Light and Tussan of Skearith’s Beak. Six black ships in the harbour, and that in itself worried Joron Twiner. That would be the first thing he addressed.

“Welcome, shipwives. Windhearth is ours.”

“Those who would join us are being taken to the ships,” said Coult. “Those who will not are being dealt with.”

“He means they will be taken to the Gaunt Islands, Deckkeeper Twiner,” said Brekir.

“If we have room,” said Coult, but not loudly, not to the room. He let the words out to be heard, to test them.

“I am sure we can find room,” said Joron. “But first, charts. Six ships in one place is too many so I would tell you what to be about. Aelerin, if you would.” The courser stepped forward, their robes bright white among the black of Twiner’s shipwives. They spread a chart over the table.

“We are here,” they said, soft voice filling the room. “Windhearth. The majority of the Hundred Isles fleet has drawn back to be nearer Shipshulme Island so they can protect Bernshulme from incursions now we have weakened their fleet so. Though there are still many patrols, and a couple of big ships out looking for us.”

“So it is important we are not trapped here. Coult,” said Joron, “I would like you to take Bloodskeer and Beakwyrm’s Glee and head here.” He pointed at an island. “It is another store island and should be no more well defended than this place.” He looked up, Coult nodded. “Go now. The less time we are here the less likely we are to be trapped.”

“And if I see Hundred Isle ships, Deckkeeper Twiner?”

“If they are small and you can catch them, destroy them. But take their officers and question them first. Be wary of being led into a trap.”

“And I would be nothing else.”

“Of course,” said Joron. Then turned from him. “Brekir, take Snarltooth, Shipwife Tussan and Skearith’s Beak and head for here,” he tapped the map, “Taffinbur. We are told there is some sort of message post. I would have it destroyed, and if you can take the messages and someone who understands the codes then all the better.”

“Ey, I shall do that.”

“Good. I will take Tide Child and, accompanied by Shipwife Chiver with the Last Light, head back to the Gaunt Islands to speak to Tenbern Aileen and see what she plans for us. We have wreaked enough havoc and weakened the Hundred Isles in a thousand ways. She must be ready to assault Bernshulme now.” Nods and smiles met his words. “Then be about it, I will not have us caught here.” He touched Brekir on the arm.

“I would speak with you alone a moment,” he said. She nodded and smiled, it had become a habit of his that he indulged when he could, to talk with her after a meeting. They waited as the other shipwives left the cabin. Then Brekir took a step nearer; he smelled her perfume, a mixture of salt long soaked into clothes and the earthy smell of the gossle that she burned in her cabin, to chase away the pains of long years on the sea and the many wounds and aches it had brought her.

“Meas may not be in Bernshulme, Joron,” said Brekir.

“She must be,” he said.

“It has been a year, Joron. And no one has heard a thing about her.” She touched his arm, gentle, comradely. “Maybe it is time you stopped calling yourself deckkeeper and took on the two-tail…”

“No,” he said and knew the word came out harsher than Brekir deserved. “When all avenues are exhausted, when every island has been searched and nothing found. Then, maybe then, I will call myself shipwife, but she is Lucky Meas, Brekir.” Was he begging her, was that the tone in his voice, the catch in his throat? “She is the one the prophecy of the Tide Child speaks of. She will bring the people together in peace. She cannot be dead. Cannot. And if I were to take on the two-tail, what message does that send to the crew, to all the crews? That I have given up hope.” Brekir nodded. Took her hand from his arm.

“It is a lonely thing, command, Joron Twiner.”

“Ey, well, I do not dispute that.” Behind Brekir sat the great cabin’s desk, as comfortable in its place there as he was not. And behind the desk sat Meas’s chair and from the upright of the chair hung her two-tailed hat, the symbol of a shipwife’s command.

“Well,” said Brekir, stepping back, “do not forget, Joron Twiner, you have friends among those you command.”

“Ey,” he laughed. “And rivals.”

“There is always that.”

“And worse.”

“That is partly why I would ask you again to put on the two-tail, Joron.”

“Wearing a shipwife’s hat will not make me any more legitimate in the eyes of Chiver and Sarring, Brekir.”

“No,” she said, “they are fleet through and through and will never truly accept one of the Berncast in command over them, you are right. But just wearing that hat will make you harder to undermine.”

“Among the officers, maybe,” he said. “But among the deckchilder?” He stared into Brekir’s eyes. “No. I made a vow. They will never respect me if I go back on it. They will see me as unlucky and to lose the deckchilder is to lose our fleet, Brekir. Let Chiver and Sarring complain, as long as I have the deckchilder by me they can do nothing.” She nodded.

“How hard it is, to command a boneship, to juggle all these duties and loyalties so the thing will fly,” said Brekir. “I think few are aware of it. Even fewer how hard it is to command a fleet of them.” Now it was Joron’s turn to nod. “Just so you know, they mean to call you out at the next meeting of shipwives.”

A settling within him, cold still water. He had always known this would come.

“A duel?”

“No, they cannot duel you; to fight a one-legged shipwife, and a man at that, would be beneath them. They will say we fight for nothing.” Joron turned and took the seat behind the desk which sat so comfortably in its position, motioned Brekir to take the one opposite him and she did. Folding her tall, long-limbed frame up in thought, her skin even darker than his, her face gifted by nature a constant look of sorrow.

“Maybe they are right, Brekir. Meas had a plan no doubt, for ending war. I have no such thing. Sometimes I wonder if it is that which drives me to find her, not loyalty.” He took a bottle of anhir from the drawers of the desk and poured two cups, passed one over to Brekir.

“Do not doubt yourself,” she said. “You have served us well this long. They will argue for carving out a berndom of our own, that we have enough ships to do it.” Joron turned away, so as not to expose the ruined skin beneath the wrapped scarf he used as a mask as he sipped the anhir, let the liquid add to the constant burn in his damaged throat. Pulled down the soft black material and turned back.

“Well, maybe that is one way to stop the war. I can think of few things that would bind together the Hundred and Gaunt Islands quicker than someone stealing their land for a new Berndom.”

Brekir leaned forward.

“Just to play Hag’s lawyer on this, Joron,” she said. “We could hold our own, we have a mighty weapon, in you.”

That cold ocean within him became ice. His words emerged as cold and sharp as the frozen islands that would slice a boneship open from beak to rump.

“We do not talk of that.”

“I think we must, Joron, you can raise keysh—”

He cut her off, his voice quiet but stern and brooking no further argument. “And the moment I act, raise a sea dragon, Meas is dead, you know that. They have her because of what they believe she can do. If they know she cannot do it, then they have no reason to keep her alive.”

“The keyshans are rising anyway, Joron. Small ones are being seen all the time, fifteen at the last count.”

“If I break another island and one person escapes to tell of it, Brekir, she is dead. I will not do it.” Brekir nodded, sipped her drink.

“I knew you would say that, and you are right of course, but it may come to it, Joron, one day, that you have to choose. Our fleet or her.” He took a drink and Brekir leaned forward. “Some friendly advice,” she said.

“Always welcome from you, Brekir.”

“Chiver is the more forceful of the two personalities. You should have Cwell pay them a visit in the night. Then all of your problems are over and you can either advance their deckkeeeper, who will owe you, or put your own woman in. Sarring will

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...