- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

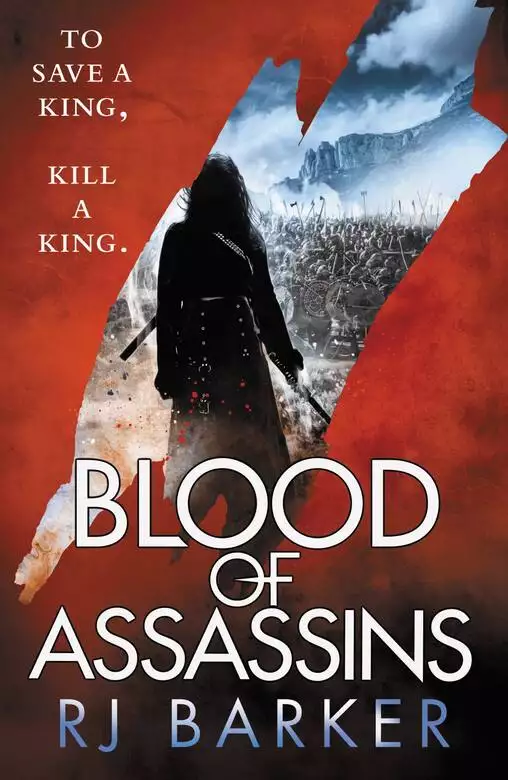

TO SAVE A KING, KILL A KING . . .

The assassin Girton Club-foot and his master have returned to Maniyadoc in hope of finding sanctuary, but death, as always, dogs Girton's heels. The place he knew no longer exists.

War rages across Maniyadoc, with three kings claiming the same crown - and one of them is Girton's old friend Rufra. Girton finds himself hurrying to uncover a plot to murder Rufra on what should be the day of the king's greatest victory. But while Girton deals with threats inside and outside Rufra's war encampment, he can't help wondering if his greatest enemy hides beneath his own skin.

Release date: February 13, 2018

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 480

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Blood of Assassins

RJ Barker

The inestimable Ed Wilson for some high quality agenting and for sending Age of Assassins on a worldwide and multilingual adventure. My editor, Jenni Hill, whose gentle nudges in interesting directions are always welcome and my American editor, Lindsey Hall, who is round and about doing the same. Also, the rest of the wonderful team at Orbit: Joanna, Emily, James, and Nazia, my publicity officer, who has sent me off on some excellent adventures (and the unknown Orbit people I know are there but never meet. Oh! and Ellen and Nita in America.). I’d also like to thank Hugh the copyeditor, one of the unsung heroes of the literary world, who spends a lot of time making me look less stupid than I really are. Thank you, Hugh. I put a deliberate error in them for you, I thought you’d like it.

Matt, Fiona, Marcy and Richard for reading the early versions and offering their opinions which were, as always, useful and well thought out. (Even when you were clearly wrong.) Tim Payne for his technical assistance, thank you kindly.

My fellow 2017 debut authors who have gone a long way to making this year one that has been very funny and full of joy, so if you have enjoyed Age of Assassins and Blood of Assassins you could do worse than check out the books by Anna Stephens, Ed McDonald, Nicholas Eames, Anna Smith-Spark, Melissa Caruso and the tidily bearded Lee James Harrison (1*ol*cy8l).

All the nice people who have asked me to come and witter on at their conventions, top work. Stephen J Poore who was kind enough to invite me up to Sheffield to do my first ever reading, there will be others, I am sure, but, Stephen, you will always be my first. Michael W. Everest who was kind enough to show me round the Facebook fantasy forums. A big thank you to everyone who reviewed Age of Assassins and liked it, and those who didn’t like it, because the world would be very dull if we all liked the same stuff. Though, I suppose, it’s unlikely you’ll be reading this if you really hated it, but it’s the thought that counts.

Lastly, Lindy, for being Lindy and Rook for being amusing, and sometimes even being quiet when I ask. And our families who go a long way to making life as pleasant as it currently is.

I am sure, by the time this has seen print, there will be a whole host more people I want to thank but that’ll have to wait for King of Assassins. As ever, if you should be here but you’re not, mea culpa.

RJ Barker

Leeds, July 2017

A ground mist was rising. The sun brushed the dew-soaked grass, and after days walking through the stink and dirt of the eastern sourlands the riotous excitement of yearsbirth made me drunk on the scent of early-morning blossom. Far over the horizon the Birthstorm swelled, towering pillows of dark cloud that heralded the giant storm which told us yearsbirth was truly here.

It felt like a weight on my back.

The mercenaries came upon us in that moment when the world seemed unreal – poised between outgoing night and incoming day. Six attacked, four men and two women of the Glynti, a hard and relentless people from the arid mountains far across the Taut Sea, where water was as valuable as bread and those who could not prove their worth were killed out of hand. If our attackers had been men of Maniyadoc they would have come for me first, seeing a man in armour as more of a danger than a woman, but they were not. The Glynti tribes kept to the old ways, and besides, if they hunted us they knew who we were. They knew my master was the real danger.

Four went for her, two for me. They had roarers, long sticks that sent out shards of sharp metal in a cough of smoke and fire; as weapons they are as ugly and as poor at killing as most Glynti. One exploded, killing its bearer and wounding the woman with him. The other made a horrendous noise and shredded a small bush by my side.

My master and I were tired, we fought in silence.

The Glynti are fierce but rely on numbers and savagery. I had spent five years as a mercenary, stood in shieldwalls facing down charging mounts and wasn’t scared of a few men and women in animal skins, no matter how hard they fought.

“I’ll skin you alive, boy,” hissed the huge Glynti, the first to approach me. His long beard was dyed with a blue stripe and his blond hair was tied in braids which snaked out from underneath a rusted helmet. In one hand he held a heavy sword and in the other he twirled a skinning knife, laughing all the while. “I’ll carve the skin from your bones, child,” he said, his mouth an unkempt wall of missing teeth.

I have lain back in silence while my master carves magical glyphs which twitch and move of their own accord into my flesh.

I am not afraid of pain.

“In truth, I’ve never been comfortable in this skin.” I smiled at him, and for a moment he was confused, but only a moment. He feinted with his knife. I ignored it. Then he brought his sword over and let its weight bring it down on me. I angled my large shield, taken in single combat from a Loridyan champion and painted with a bleeding eye, and his blade slid away on it and bit into the earth as I brought the beaked warhammer, taken from a man I had killed in vengeance, round in a swing which punched a neat hole in his helmet and felled him.

I glanced over at my master. She fought with two stabswords, dancing lithely in and out of the flashing blades of her attackers as if they did not exist. For a moment her skill stole my breath away, and then the second Glynti was on me. This one was far more careful and held a long spear – a better weapon against an armoured man with a shield – but like his fellow he was too used to ferocity winning his battles. His only skill lay in attack and he lacked the warrior’s greatest ally – patience. He came in, jabbing his spear against my shield with a teeth-grating screech of metal on metal. As he jabbed again I put all my strength into a forward push of the shield. I felt the strength of his blow in the jarring of my shoulder joint. He felt it in his hands and though he did not drop the spear his control of it lapsed for long enough to let me in close. The warhammer rose and fell, rose and fell, rose and fell until his head was a pulpy mush of grey brains, white bone and bright red blood.

“Girton –” my master’s soft voice behind me “– they are done.” Blood dripped from a cut on her arm. It ran down her hand, along the hilt of her stabsword to mingle with the Glynti blood that stained her blade. It was only when she spoke that I heard myself, heard the noise that I was making, the screaming of an animal. I dropped my weapon in the mud. The warhammer was heavy.

“One still lives,” I said, and pointed at the woman who had been felled when the roarer exploded. I walked towards her, unsheathing the black metal stabsword I kept on my left hip.

“Wait, Girton.”

“Why?” I continued towards the woman, she was burned down one side but had no killing wounds. “She will only tell others where we are.”

“Wait!” My master jumped over a corpse and ran to me, grabbing my arm just as I was about to kneel down and slit the wounded woman’s throat. “There are better ways.” I stared at my master, the muscles of my arm tight against her grip.

“So you say.” I brushed her hand from my arm and sat back on bloodied grass.

The burned woman watched all this with eyes as bright as those of the black birds of Xus the unseen, god of death.

“Your lover is fierce even though he’s mage-bent, Merela Karn,” croaked the woman to my master. If she had ever had beauty for the burns to spoil it had long since fled.

“He is not my lover,” said my master.

“Are you one who prefers women, then? He is young, strong …”

“Quiet!” My master grabbed the woman’s face with her hand, breaking the burned skin around her mouth and leaving a raw fingerprint that had the woman hissing in pain. “What tribe are you?”

The Glynti woman had eyes like a hunting lizard, as blue as the sky they dived from and full of the same scorn for life.

“Geirsti.” she said, the name of her tribe distorted by my master’s hold on her face and the pain of her burns.

“And your name?”

“Als.”

“Well, Als of the Geirsti. Listen to me. I am Merela Karn and my companion is Girton Club-Foot. We have killed many Glynti as we travelled back to Maniyadoc. Seventeen of the Corust, twelve of the Jei-Nihl and fourteen of the Dhustu. By my reckoning that means if you head back to your mountains the Geirsti will outnumber the other tribes. Take this information to your leader, conquer new lands and send no more of your young to die in search of the price on our heads.”

The Glynti woman stared at my master. Before she replied we were interrupted by a grunt from behind us. I turned, the first man I had hit with the hammer was convulsing.

“My man,” said the tribeswoman. “He fought well. Let your boy give him a good death, and I will consider what you say.” I looked to my master and she gave me a nod so I walked over and slit the man’s throat with my black blade. By the time I returned the Glynti woman was on her feet. “I will give your message to our clanwoman.”

“My master told you to stop sending people after us …” angry steps towards her, blade in my hand, but my master held me back once more.

“Thank you, Als of the Geirsti,” she said. “Leave here and die well.”

The woman staggered away into the ground mist, turning at that moment when wisps of thickened air made her look like a ghost.

“I will die well,” she said, “but you won’t, Merela Karn. No, you won’t. You will die hard.” The moist air swallowed her figure, leaving only laughter behind.

“She did not promise to leave us alone,” I said. “You should have made her promise to leave us alone, or killed her.“

“One more Glynti won’t make a difference in the great scheme of things. Girton, but if I can convince them to start a tribal war they’ll be too busy killing each other to come after us. The Geirsti are the biggest tribe, and …” Her voice tailed away and when I turned to her she looked stricken, her dark skin grey with shock “Geirsti,” she said, and stared at the cut on her arm. “Dark Ungar’s stolen breath,” she hissed, “the Geirsti are poisoners.” As she spoke she was pulling the rawhide cord from the neck of her jerkin and wrapping it around the top of her arm. “Girton, start a fire, hot as you can get it. Quickly.”

“Yes, Master.” A cold fell upon me, far deeper than could be explained by the yearsbirth morning chill, and it froze the simmering resentment that had been my companion for the years of our exile. I was running almost before I was aware of it. Wood is sparse in the Tired Lands, especially so near the border of the sourlands, but I found a derelict haystack, sodden with dew on the outside, and I burrowed within to pull dry grass from it. Beyond the haystack was a field where cows had been kept, and dry circles of dung punctuated the grass. When I returned my master had wrapped the cord so tightly around her bicep that her forearm had ballooned up and gone corpse blue.

“Quickly, Girton.” My hand shook as I struck flint to steel. The flame refused to catch, as if the morning mist sought to foil me by sucking away the sparks. Finally I got an ember and set the grass to crackling, but I could see impatience on my master’s face and knew the fire would not be hot enough quickly enough. “Give me your Conwy blade,” she hissed.

“Why?” I asked. Stupid, time-wasting words.

“Because mine have crossed with the Geirsti’s weapons and yours never leaves its scabbard,” she spat. “Give me it.” Her hand flashed out. I pulled the blade from the scabbard at my back and handed it to her; she gave me hers. “Stick this in the fire, Girton, get it hot, you know what to do.” I nodded. “The poison acts quickly. I don’t have time to wait for mine to heat so I will lose a lot of blood. Be ready.”

“Wait, Master.” And I was scared, like a child. “I should check the bodies for an antidote.”

“You would know it how?”

I stood, my hands trembling, fear chasing anger in circles like a mad dog after its tail.

“I could go after the woman.”

My master shook her head. “I’d be dead before you got back.” She gritted her teeth against a spasm of pain. “No. It must be this way and we must be swift – I do not want to lose my hand. Give me your belt.” Her teeth were chattering as I slipped the thick leather belt from my skirts and passed it to her. She paused before folding the leather double and forcing it into her mouth so she could bite down on it. Then she stared into my eyes, removed the belt for a second. “If I pass out, Girton, you must finish this.”

“Yes, Master.” Fear returned: fear of losing her, fear of being alone. She gave me a small smile, bit down on the leather and started taking short deep breaths through her nose. Then she nodded to me and pushed my knife into her wounded left arm.

She screamed against the leather belt, more in fury than pain, when she pushed the razor edge into her flesh three fingers’ breadth above the wound. Then she forced the sharp metal down into her arm and along the bone, growling and moaning like an animal all the while. With a sound like a rotten apple being squashed underfoot the blade came out of her, taking a chunk of flesh as long as my fingers with it. Her hand convulsed, and my Conwy stabsword fell from it as she slumped forward, unconscious. I dived for her, grabbing her hand and pulling it into the air with one arm and using my other to cradle her limp body against me. Thick blood poured over my arm as I lay her down on the damp grass and pushed a cloth hard against the wound, the muscles in my arms straining and sweat starting from my forehead as I worked to keep up the pressure. I willed the knife in the fire to speed its way to glowing cherry red. “Don’t die, don’t die,” going round and round in my head like a ride at Festival. The thicket of scars on my chest that kept the magic in check writhed as the dark flow within tried to rise up and take advantage of my fear.

When the blade was hot enough I cauterised the wound in my master’s arm – I doubted she would ever have the same skill with a blade after this – then I covered her in blankets from our packs. There was nothing else I could do past that so I sat, miserable, in front of the fire and tried not to think of the agony she had just put herself through or of how much mental discipline was required to cut out such a large piece of yourself.

I could not have done it.

The sun burned away the mist and winged lizards trilled a welcome to yearsbirth, flowers opened their colourful eyes in search of the sun, but I was as blind to them as they were to me. Somewhere, far in the distance, thunder rumbled.

One foot in front of the other.

The rope straps of the travois bit into my shoulders and my master moaned and sweated. I had watched for a day and a night as the poison raged within her but had never crossed from my side of the fire to go to her. I had wanted to, but even as she fought with death there was a gulf between us – one scored out by the knives she had used to cut progressively deeper sigils in my flesh – and though I understood, had even asked for them, it was still hard not to resent her for it. There had been a moment, in the darkest part of the night while the moon hid her face behind silver clouds, when I had thought her battle over – lost.

Breathe out.

The mixture of poison and blood loss had weakened her– her breathing stopped – and there was silence. The fire cracked and popped in the darkness and the flames rose like a hedging come to catch a lost spirit. With our gods dead there would be no return to the land for my master. She would reside quiet in the dark palace of Xus the unseen, god of death, until the world was made again and the hedgings threw themselves into the sea from where the gods would be reborn.

But maybe the fire was not a hedging, maybe the heat was a wall that held her spirit prisoner.

Breathe in.

As the light of the sun returned to the land so the light of life returned to her. She was not strong and her eyes did not open, but her breathing took on a regularity it had lacked in the night and it was as if I was released from a spell. Only then could I move, stiff and aching, to go find fuel for our dying fire. As I searched in the weak light I became convinced I was watched. I would catch movements from the corner of my eye – the Glynti. It was unlikely anyone from Maniyadoc would come this near to the sourlands, and as the Glynti woman knew my master had been poisoned it made sense for her to wait rather than attack. Maybe she had more warriors with her or maybe she waited for more to come. Either way, I did not feel safe going beyond where I could see my master, and eventually I had made the travois by lashing together the Glynti roarers, spears, my shield and sacrificing my long bow. Then I began the long trek towards Maniyadoc where I hoped to find Rufra, the king, and my only friend.

One foot in front of the other. Sometimes it is the only thought you can allow yourself. When your muscles ache, when your master moans, when your back itches like a target for unseen weapons, when you are sure you are followed and that attack is inevitable.

One foot in front of the other.

One foot in front of the other as the ropes bite into your flesh. If Fitchgrass himself had jumped from the fields – a twisted mass of prickles, burrs and sly promises in the shape of a man – I would have sold my spirit to it for rest and my master’s health.

But it did not, and there was only one foot in front of another.

Maniyadoc had changed in the five years I had been away, selling my sword and my morals to the highest bidder while trying to stay ahead of the Open Circle’s assassins. I had seen much of war: we had spent half a year with the Ilstoi of the far seas, they believed that if you angered the land it would form itself into a giant and smash all you owned and loved, replacing it with a carpet of green. It looked like one of these Ilstoi giants had been loosed in Maniyadoc. I trudged past farm buildings collapsed in on themselves and thick with grasses and small trees. Only when you looked more closely did you see the black scars of fire on timbers and the unnaturally straight cut marks of swords and axes. In other places the grass grew strange and thick, and when I put down the travois to forage along the sides of the roads for water I found bleached bones among the lush growth. I was not surprised. War had been my business for five years and it raged nowhere fiercer than in Maniyadoc where the three kings, Tomas, Aydor and my friend Rufra, warred for supremacy and access to the scant resources of a land scarred by the actions of ancient sorcerers.

Sorcerer. That word still sent a shudder through me, despite, or maybe because, I am one. As always when I thought of magic my mind slid away to other memories, replacing fear of what was in me with hate or anger.

The face of my lover, Drusl, in the stable, as she cut her throat to return her magic to the land.

A pain in my chest so fierce I had to stop. There had been other women, and men, since Drusl, but only one I had become close to, and even then it had not been love. The secrets inside me had killed Drusl and I held them close. Who I am and what I am could never be aired. I could not let myself get close to anyone, not truly close, and so I had not.

I walked on, one foot in front of the other, past fields overrun with weeds. In one place the road was verged with blood gibbets. I counted twenty, each one marked with the parched branch and tattered flag of a white tree on a green background that belonged to the Landsmen. Once, the blood gibbet, with its tortuous machinery of windmills and blades, had been solely for magic users, but above many of these were wooden plaques with “TRAITOR” burned into them. Some had no sign above them, but all contained bodies in various states of decay, many wearing the red and black I knew Rufra had taken for his colours. It seemed the war had allowed the Landsmen to run rampant with their cruel punishments, and they had gone beyond their usual search for magic users. This close to the sourlands the stink of putrefaction was barely discernible.

In the last of the blood gibbets was a man, young, emaciated and crack-skinned. He croaked something, whether begging for water or food I do not know. He wore the yellow and black that showed he was one of Aydor’s men. I had tangled with Aydor before and had been instrumental in putting Rufra on his throne. He had been a cruel, stupid boy who killed for his own amusement; I had nothing but hate in me for the old king’s heir. No doubt he had grown into a cruel and stupid leader. I walked on, leaving the man to his fate.

One foot in front of the other.

I kept my eye open for signs of assassins, the subtle signposts of the Open Circle – knotted grass, a scratched post, an arrangement of flower petals, but though death was everywhere signs of assassins were curiously absent. Occasionally I found a bit of scratch, but the requests were either struck through as fulfilled or so worn as to be clearly years old. My master had said that the Open Circle generally avoided war; our skills were wasted in the shieldwall. When I questioned why we were fighting in them she would not answer. But still, it appeared the Open Circle were not active in Maniyadoc, and that made me a feel a little safer.

As the midday sun burned away the last of the morning chill the Glynti made their move. I was passing through a steep-sided gulley, a place where it seemed a massive axe had scored a furrow in the middle of a wooded copse, and the branches, late to leaf, were a skeletal lacework of black against blue sky. A voice rang out and stilled the singing of the winged lizards.

“Stay still, boy. Stay or we shoot.”

The voice of the woman we had let go. I put down the travois and slowly unstrapped the warhammer from my thigh. It was a crude and vicious weapon, a hardwood staff topped with a head made of glittering stone. One side was beaked for punching through armour and the other rounded for breaking limbs. I itched for my shield, but it was too securely worked into the travois for me to get at.

“I knew I should have killed you,” I shouted into the wood, emboldened by the weight of the hammer in my hand.

“You should have,” rang the reply, bouncing from tree to tree and robbing itself of direction and distance as it worked its way down the steep and mossy slopes. “But as my life was spared I will give you one chance. The woman is dead already, you must know that. The poison cannot be stopped. Leave her there and walk away. Do that and we will not shoot you down.”

“I wanted you dead, woman – you owe me no favours,” I shouted back. “I think you bluff, I think there is only you and you wish me to walk away so you do not have to face me.”

The woman laughed, a rich and hearty sound, and then she let out a piercing whistle. Glynti appeared from behind trees – only for the briefest second. I counted five but heard more behind me. I felt no fear, only an ache in my arms from the weight of the warhammer.

“We have numbers, boy.”

“Then why let me live?”

A pause. Almost long enough for the timid winged lizards to begin their disturbed song again.

“You killed my man, maybe I want you as a replacement, eh? I’m giving you a chance to live, mage-bent boy. Take it.”

She thought me a boy as I am small. Many make that mistake and it is their last.

“I will not leave my master.” I spread my arms. “Shoot your arrows if you have them.”

My breath came slowly and the world took on a rare clarity: branches bobbed, the fuzzy promise of life in their buds, grass waved and the sun warmed my skin.

No arrows came.

The wood rang again with the woman’s laughter.

“You’re a brave one, I’ll give you that.” She let out a piercing whistle and the Glynti appeared from behind the trees. Twelve of them, eight men and four women, including her. “You can’t stand against us all, child.” They pushed through knee-high bracken, treading carefully as they came down the steep slope. Eight stopped in front of me and the rest took up positions to my rear. A calm fell on me. It was like this before most battles – a time for readying yourself, for checking weapons and armour, preparing your mind for the moment to come when you took a life or lost your own. The Glynti hefted their weapons. The eight were going to rush me; the other four were there purely to make sure I did not escape.

“Come, boy,” said the woman. “This is your last chance. Your master is dead in all but flesh. Walk away. I will still allow it.” She picked a scab from one of the burns on her face and flicked it away. “We are not a greedy people; another can have your price.”

“No.”

“Walk away, boy.”

“No.”

“I will not ask again.”

“Good. I am tired of talking.”

She shrugged, and the men around her organised themselves into a rough shieldwall; their circular shields had been polished to a sheen and reflected distorted trees back at me. As I readied myself, choosing how I would die on their charge and which Glynti I would take with me to Xus’s dark palace, an argument broke out. A tall warrior with long, dyed-red braids was shouting at the woman in Glynti, a language I didn’t understand. She shouted back at him and occasionally they would point at me.

“Brank would avenge his brother, boy.” she shrugged. “But I have seen you fight and do not want to lose another bedmate.”

“Then you and your people may walk away,” I said, then added, “I will allow it.”

She chuckled, shaking her head and looking at the ground.

“It is a pity you will die, I would have enjoyed you. You have spirit.” She motioned Brank forward.

The warrior came on at a crouch with his shield raised and his curved sword held high. I waited for him to come near and thought that, had he been less of a fool, he would have brought a spear. He launched a swing at me with his sword and I jumped back, avoiding the blade. He brought his shield up, an instinctive reflex but the wrong one. The hammer came down, with all my strength behind it, on the shield – and like all Glynti shields it was a flimsy thing, thin metal over wood, and it shattered, as did the bones in the arm that held it. With a scream Brank launched himself at me, swinging his sword overarm. I grabbed the haft of the warhammer, one hand at the hilt, the other below the head, and blocked his blade.

Even though he was one-handed and in pain it was a jarring blow, and he followed it up with another and another, forcing me back until I tripped over a rut in the path. Brank aimed another blow and I twisted the hammer so his blade hit the stone end, shattering the sword’s poor-quality metal. Then I brought round the pommel, crowned with the claw of some fearsome beast, and ripped the man’s stomach open. I started to push myself up, thinking him beaten, but he threw himself at me, his entrails looping around our bodies as he knocked me back to the ground. As we rolled in the dirt in his blood and shit he managed to get one huge hand around my throat, squeezing the life out of me even as the life drained from him.

Breath hissed in and out of his teeth. I could smell the tang of his last meal and the badly cured hides he wore as armour. Through the trees behind him I thought I saw Xus the unseen fluttering though the shafts of sunlight. Reaching up I grabbed Brank’s head, pushing my thumbs into his eyes and forcing a scream out of his mouth. Even blinded he kept his hand clamped around my throat, his thirst for vengeance overwhelming his pain.

My hand scrabbled at my side, looking for my stabsword. My vision began to swim and all feeling fled from my body. Did I have the blade? I didn’t know. Time was running out. Above the Glynti hovered a figure of shadow and sadness. With all my strength I thrust my arm forward. It seemed every scar etched into my chest convulsed, grasping my body far tighter than Brank’s hand around my neck, thrusting blades into my flesh. And then I was breathing, coughing and choking on the air, and the weight of the Glynti was gone from my chest.

I lived, for what it was worth.

The remaining Glynti had gathered around while I fought, standing in a ring, swords and spears extended towards me and faces twisted in disgust and horror. The body before me had a smoking hole where his throat should be and my blood sang a sweet and sickly song in my ears.

“Sorcerer,” hissed the woman. “Maniyadoc’s filth.” She drew back her blade for a killing stroke and I did not have the strength to stop her.

The arrow took her though the throat and she fell, coughing, to her knees. The remaining Glynti turned as archers emerged from the undergrowth and the air filled with the thunder of mounted troops. Another round of arrows felled more Glynti and then three huge mounts charged in, heads down, lethal antlers sweeping from side to side to cut down anyone in their way with razor-sharp gildings. In moments the Glynti were dead and I was surrounded by armoured soldiers. They wore no colours and flew no loyalty flags, only stared down at me – suspicious eyes behind grimacing fa

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...