- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

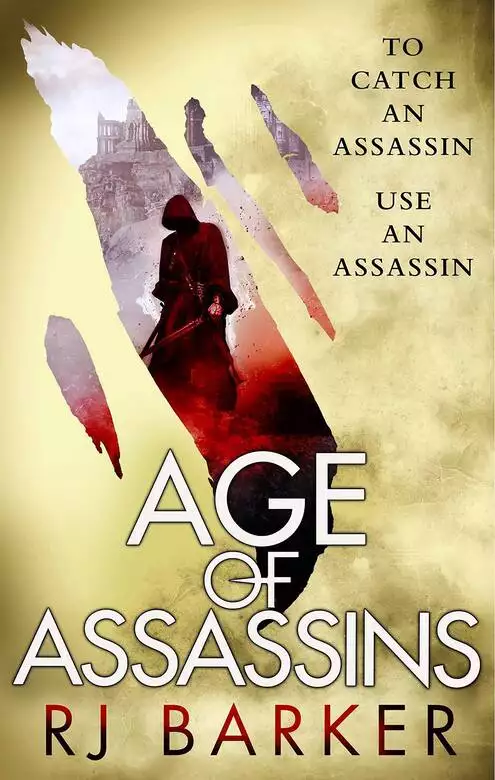

TO CATCH AN ASSASSIN, USE AN ASSASSIN . . .

Girton Club-Foot, apprentice to the land's best assassin, still has much to learn about the art of taking lives. But their latest mission tasks him and his master with a far more difficult challenge: to save a life. Someone, or many someones, is trying to kill the heir to the throne, and it is up to Girton and his master to uncover the traitor and prevent the prince's murder.

In a kingdom on the brink of civil war and a castle thick with lies Girton finds friends he never expected, responsibilities he never wanted, and a conspiracy that could destroy an entire land.

Release date: August 1, 2017

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 432

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Age of Assassins

RJ Barker

“Shh, child. Soonest done, soonest over,” he said, and then the knife bit into her neck and her tears were stilled for ever. Darik glanced between the bars of his hair and saw Kina’s body jerking as blood fountained from her neck and made dark, twisting, red patterns on the stinking yellow ground—silhouettes of death and life.

He had hoped to marry Kina when she came of age.

Darik was cold but it was not the wind that made him shiver; he had been cold ever since the sorcerer hunters had come for him. It was the first time in fifteen years of life that the sweat on his skin wasn’t because of the fierce heat of the forge. The moisture that had clung to him since was a different sweat, a new sweat, a cold frightened animal sweat that hadn’t stopped since they locked the shackles on his wrists. It seemed so long ago now.

The weeks of marching across the Tired Lands had been like a dream but, looking back, the most dreamlike moment of all was that moment when they had called his name. He hadn’t been surprised—it was as if he’d sold himself to a hedge spirit long ago and had been waiting for someone to come and collect on the debt his whole life.

“Shh, child. Soonest done, soonest over.” The knife does its necessary work on another of the desolate, and a second set of bloody sigils spatters out on the filthy yellow ground. Is there meaning there? Is there some message for him? In this place between life and death, close to embracing the watery darkness that swallowed the dead gods, are they talking to him?

Or is it just blood?

And death.

And fear.

“Shh, child. Soonest done, soonest over.” The next one begs for life in the moments before the blade bites. Darik doesn’t know that one’s name, never asked him, never saw the point because once you’re one of the desolate you’re dead. There is no way out, no point running. The brand on your forehead shows you for what they think you are—magic user, destroyer, abomination, sorcerer. You’re only good for bleeding out on the dry dead earth, a sacrifice of blood to heal the land. No one will hide you, no one will pity you when magic has made the dirt so weak people can barely feed their children. There is the sound of choking, fighting, begging as the knife does its work and the thirsty ground drinks the life stolen from it.

Does Darik feel something in that moment of death? Is there a vibration? Is there a twinge that runs from Darik’s knees, up his legs through his blood to squirm in his belly? Or is that only fear?

“Shh, child. Soonest done, soonest over.”

The slice, the cough, blood on the ground, and this time it is unmistakable—a something that shoots up through his body. It sets his teeth on edge, it makes the roots of his hair hurt. Everything starts changing around him: the land is a lens and he is its focus, his mind a bright burning spot of light. What is this feeling? What is it? Were they right?

Are they right?

A hand on his forehead.

Dark worms moving through his flesh.

The hiss of the blade leaving the scabbard.

He sweats, hot as any day at the forge.

His head pulled back, his neck stretched.

Closing his eyes, he sees a world of silvered lines and shadows.

The cold touch of the blade against his neck.

A pause, like the hiss of hot metal in water, like the moment before the geyser of scorching steam hisses out around his hand and the blade is set.

The sting of a sharp edge against his skin.

And the grass is talking, and the land is talking, and the trees are talking, and all in a language he cannot understand but at the same time he knows exactly what is being said. Is this what a hedging lord sounds like?

The creak of leather armour.

“I will save you.” Is it the voice of Fitchgrass of the fields?

“No!”

“Only listen …” This near the souring is it Coil the yellower?

“Shh, shh, child.” The Landsman’s voice, soothing, calming. “Soonest done, soonest over.”

“I can save you.” Too far from the rivers for Blue Watta.

“No.” But Darik’s word is a whisper drowned in fear of the approaching void. Time slows further as the knife slices though his skin, cutting through layer after layer in search of the black vessels of his life.

“Let me save you.” Or is it the worst of all of them? Is it Dark Ungar speaking?

“No,” he says. But the word is weak and the will to fight is gone.

“Let us?”

“Yes!”

An explosion of … of?

Something.

Something he doesn’t know or understand but he recognises it—it has always been within him. It is something he’s fought, denied, run from. A familiar voice from his childhood, the imaginary friend that frightened his mother and she told him to forget so he pushed it away, far away. But now, when he needs it the most, it is there.

The blade is gone from his neck.

He opens his eyes.

The world is out of focus—a haze of yellows—and a high whine fills his ears the way it would when his father clouted him for “dangerous talk.” The green grass beneath Darik’s knees is gone, replaced by yellow fronds that flake away at his touch like morning ash in the forge. He stares at his hands. They are the same—the same scars, the same half-healed cuts and nicks, the same old burns and calluses.

Around him is perfect half-circle of dead grass, as if the sourlands have taken a bite out of the lush grasslands at their edge

His wrists are no longer bound in cold metal.

Is he lost, gone? Has he made a deal with something terrible? But it doesn’t feel like that; it feels like this was something in him, something that has always been in him, just waiting for the right moment.

He can feel the souring like an ache.

There had been four Landsmen to guard the five desolate. Now the guards are blurry smears of torn, angular metal, red flesh and sharp white bone.

Darik rubbed his eyes and forced himself up, staggering like a man waking from too long a sleep. A movement in the corner of his eye pulled at his attention. One of the Landsmen was still alive, on his back and trying to scuttle away on his elbows as Darik approached. The smith knelt by the Landsman and placed his big hands on either side of his head. It would be easy to finish him, just a single twist of his big arms and the Landsman’s neck would snap like a charcoaled stick. He willed his arms to move but instead found himself staring at the Landsman. Not much older than he was and scared, so scared. The Landsman’s lips were moving and at first the only sound is the high whine of the world, then the words come like the approaching thunder of a mount’s feet as it gallops towards him.

“I’msorryI’msorryI’msorryI’msorry …”

“It’s wrong,” Darik said, “this is all wrong,” but the Landsman’s eyes were far away, lost in fear and past understanding. His mouth moving.

“… I’msorryI’msorryI’msorry …”

Darik stared a little longer, the killing muscles in his arms tensing. Now his vision had cleared he saw beyond the broken bodies of the other Landsmen to the shattered corpses of those who had died beside him. They had been picked up and tossed away on the winds of his fury.

Darik leaned in close to the Landsman.

“This has to stop,” he said, and let go of the man’s head. The words kept coming.

“… I’msorryI’msorryI’msorry.”

He could see Kina’s corpse, dead at the hand of the knights then shredded into a red mess by his magic.

“I forgive you,” said Darik through tears. The Landsman slumped to the floor, eyes wide in shock as the smith walked away.

Inside the thick muscles of Darik’s arms black veins are screaming.

We were attempting to enter Castle Maniyadoc through the night soil gate and my master was in the sort of foul mood only an assassin forced to wade through a week’s worth of shit can be. I was far more sanguine about our situation. As an assassin’s apprentice you become inured to foulness. It is your lot.

“Girton,” said Merela Karn. That is my master’s true name, though if I were to refer to her as anything other than “Master” I would be swiftly and painfully reprimanded. “Girton,” she said, “if one more king, queen or any other member of the blessed classes thinks a night soil gate is the best way to make an unseen entrance to their castle, you are to run them through.”

“Really, Master?”

“No, not really,” she whispered into the night, her breath a cloud in the cold air. “Of course not really. You are to politely suggest that walking in the main gate dressed as masked priests of the dead gods is less conspicuous. Show me a blessed who doesn’t know that the night soil gate is an easy way in for an enemy and I will show you a corpse.”

“You have shown me many corpses, Master.”

“Be quiet, Girton.”

My master is not a lover of humour. Not many assassins are; it is a profession that attracts the miserable and the melancholic. I would never put myself into either of those categories, but I was bought into the profession and did not join by choice.

“Dead gods in their watery graves!” hissed my master into the night. “They have not even opened the grate for us.” She swung herself aside whispering, “Move, Girton!” I slipped and slid crabwise on the filthy grass of the slope running from the river below us up to the base of the towering castle walls. Foulness farted out of the grating to join the oozing stream that ran down the motte and joined the river.

A silvery smudge marred the riverbank in the distance; it looked like a giant paint-covered thumb had been placed over it. In the moonlight it was quite beautiful, but we had passed near as we sneaked in, and I knew it was the same livid yellow as the other sourings which scarred the Tired Lands. There was no telling how old this souring was, and I wondered how big it had been originally and how much blood had been spilled to shrink it to its present size. I glanced up at the keep. This side had few windows and I thought the small souring could be new, but that was a silly, childish thought. The blades of the Landsmen kept us safe from sorcerers and the magic which sucked the life from the land. There had been no significant magic used in the Tired Lands since the Black Sorcerer had risen, and he had died before I had been born. No, what I saw was simply one of many sores on the land—a place as dead as the ancient sorcerer who made it. I turned from the souring and did my best to imagine it wasn’t there, though I was sure I could smell it, even over the high stink of the night soil drain.

“Someone will pay for arranging this, Girton, I swear,” said my master. Her head vanished into the darkness as she bobbed down to examine the grate once more. “This is sealed with a simple five-lever lock.” She did not even breathe heavily despite holding her entire weight on one arm and one leg jammed into stonework the black of old wounds. “You can open this, Girton. You need as much practice with locks as you can get.”

“Thank you, Master,” I said. I did not mean it. It was cold, and a lock is far harder to manipulate when it is cold.

And when it is covered in shit.

Unlike my master, I am no great acrobat. I am hampered by a clubbed foot, so I used my weight to hold me tight against the grating even though it meant getting covered in filth. On the stone columns either side of the grate the forlorn remains of minor gods had been almost chipped away. On my right only a pair of intricately carved antlers remained, and on my left a pair of horns and one solemn eye stared out at me. I turned from the eye and brought out my picks, sliding them into the lock with shaking fingers and feeling within using the slim metal rods.

“What if there are dogs, Master?”

“We kill them, Girton.”

There is something rewarding in picking a lock. Something very satisfying about the click of the barrels and the pressure vanishing as the lock gives way to skill. It is not quite as rewarding done while a castle’s toilets empty themselves over your body, but a happy life is one where you take your pleasures where you can.

“It is open, Master.”

“Good. You took too long.”

“Thank you, Master.” It was difficult to tell in the darkness, but I was sure she smiled before she nodded me forward. I hesitated at the edge of the pitch-dark drain.

“It looks like the sort of place you’d find Dark Ungar, Master.”

“The hedgings are just like the gods, Girton—stories to scare the weak-minded. There’s nothing in there but stink and filth. You’ve been through worse. Go.”

I slithered through the gate, managing to make sure no part of my skin or clothing remained clean, and into the tunnel that led through the keep’s curtain wall. Somewhere beyond I could hear the lumpy splashes of night soil being shovelled into the stream that ran over my feet. The living classes in the villages keep their piss and night soil and sell it to the tanneries and dye makers, but the blessed classes are far too grand for that, and their castles shovel their filth out into the rivers—as if to gift it to the populace. I have crawled through plenty of filth in my fifteen years, from the thankful, the living and the blessed; it all smells equally bad.

Once we had squeezed through the opening we were able to stand, and my master lit a glow-worm lamp, a small wick that burns with a dim light that can be amplified or shut off by a cleverly interlocking set of mirrors. Then she lifted a gloved hand and pointed at her ear.

I listened.

Above the happy gurgle of the stream running down the channel—water cares nothing for the medium it travels through—I heard the voices of men as they worked. We would have to wait for them to move before we could proceed into the castle proper, and whenever we have to wait I count out the seconds the way my master taught me—one, my master. Two, my master. Three, my master—ticking away in my mind like the balls of a water clock as I stand idle, filth swirling round my ankles and my heart beating out a nervous tattoo.

You get used to the smell. That is what people say.

It is not true.

Eight minutes and nineteen seconds passed before we finally heard the men laugh and move on. Another signal from my master and I started to count again. Five minutes this time. Human nature being the way it is you cannot guarantee someone will not leave something and come back for it.

When the five minutes had passed we made our way up the night soil passage until we could see dim light dancing on walls caked with centuries of filth. My own height plus a half above us was the shovelling room. Above us the door creaked and then we heard footsteps, followed by voices.

“… so now we’re done and Alsa’s in the heir’s guard. Fancy armour and more pay.”

“It’s a hedging’s deal. I’d sooner poke out my own eyes and find magic in my hand than serve the fat bear, he’s a right yellower.”

“Service is mother though, aye?”

Laughter followed. My master glanced up through the hole, chewing on her lip. She held up two fingers before speaking in the Whisper-That-Flies-to-the-Ear so only I could hear her.

“Guards. You will have to take care of them,” she said. I nodded and started to move. “Don’t kill them unless you absolutely have to.”

“It will be harder.”

“I know,” she said and leaned over, putting her hands together to make a stirrup. “But I will be here.”

I breathe out.

I breathe in.

I placed my foot on her hands and, with a heave, she propelled me up and into the room. I came out of the hole landing with my back to the two men. Seventeenth iteration: the Drunk’s Reversal. Rolling forward, twisting and coming up facing guards dressed in kilted skirts, leather helms and poorly kept-up boiled-leather chest pieces splashed with red paint. They stared at me dumbly, as if I were the hedging lord Blue Watta appearing from the deeps. Both of them held clubs, though they had stabswords at their sides. I wondered if they were here to guard against rats rather than people.

“Assassin?” said the guard on the left. He was smaller than his friend, though both were bigger than me.

“Aye,” said the other, a huge man. “Assassin.” His grip shifted on his club.

They should have gone for the door and reinforcements. My hand was hovering over the throwing knives at my belt in case they did. Instead the smaller man grinned, showing missing teeth and black stumps.

“I imagine there’s a good price on the head of an assassin, Joam, even if it’s a crippled child.” He started forward. The bigger man grinned and followed his friend’s lead. They split up to avoid the hole in the centre of the room and I made my move. Second iteration: the Quicksteps. Darting forward, I chose the smaller of the two as my first target—the other had not drawn his blade. He swung at me with his club and I stepped backwards, feeling the draught of the hard wood through the air. He thrust with his dagger but was too far away to reach my flesh. When his swipe missed he jumped back, expecting me to counter-attack, but I remained unmoving. All I had wanted was to get an idea of his skill before I closed with him. He did not impress me, his friend impressed me even less; rather than joining the attack he was watching, slack-jawed, as if we put on a show for him.

“Joam,” shouted my opponent, “don’t be just standing there!” The bigger man trundled forward, though he was in no hurry. I didn’t want to be fighting two at the same time if I could help it so decided to finish the smaller man quickly. First iteration: the Precise Steps. Forward into the range of his weapons. He thrust with his stabsword. Ninth iteration: the Bow. Middle of my body bowing backwards to avoid the blade. With his other hand he swung his club at my head. I ducked. As his arm came over my head I grabbed his elbow and pushed, making him lose his balance, and as he struggled to right himself I found purchase on the rim of his chest piece. Tenth iteration: the Broom. Sweeping my leg round I knocked his feet from under him. With a push I sent him flailing into the hole so he cracked his head on the edge of it on his way down.

I turned to his friend, Joam.

Had the dead gods given Joam any sense he would have seen his friend easily beaten and made for the door. Instead, Joam’s face had the same look on it I had seen on a bull as it smashed its head against a wall in a useless attempt to get at a heifer beyond—the look of something too stupid and angry to know it was in a fight it couldn’t win.

“I’m a kill you, assassin,” he said and lumbered slowly forward, smacking his club against his hand. I had no time to wait for him; the longer we fought the more likely it was that someone would hear us and bring more guards. I jumped over the hole and landed behind Joam. He turned, swinging his club. Fifteenth Iteration: the Oar. Bending at the hip and bringing my body down and round so it went under his swing. At the lowest point I punched forward, landing a solid blow between Joam’s legs. He screeched, dropping his weapon and doubling over. With a jerk I brought my body up so the back of my skull smashed into his face, sending the big man staggering back, blood streaming from a broken nose. It was a blow that would have felled most, but Joam was a strong man. Though his eyes were bleary and unfocused he still stood. Eighteenth iteration: the Water Clock. I ran at him, grabbing his thick belt and using it as a fulcrum to swing myself round and up so I could lock my legs around his throat. Joam’s hand grasped blindly for the blade at his hip. I drew it and tossed it away before he reached it. His hands spidered down my body searching for and locking around my throat, but Joam’s strength, though great, was fleeing as he choked. I wormed my thumb underneath his fingers and grabbed his little finger and third finger, breaking them. I expected a grunt of pain as he let go of me, but the man was already unconscious and fell back, sliding down the wall to the floor. I squirmed free of his weight and checked he was still breathing. Once I was sure he was alive I rolled his body over to the hole.

“Look out, Master,” I whispered. Then pushed the limp body into the hole. I took a moment, a second only, to check and see if I had been heard, then I knelt to pull up my master.

She was not heavy.

For the first time I had a moment to look around, and the room we stood in was a strange one. Small in length and breadth but far higher than it needed to be. I barely had time for that thought to form on the surface of my mind before my master shouted,

“This is wrong, Girton! Back!”

I jumped for the grate, as did she, but before either of us fell back into the midden a hidden gate clanked into place across the hole. Four pikers squeezed into the room, dressed in boiled-leather armour, wide-brimmed helms and skirts sewn with chunks of metal. Below the knee they wore leather greaves with strips of metal cut into the material to protect their shins, and as they brandished their weapons they assaulted us with the smell of unwashed bodies and the rancid fat they used to oil their armour. In such a small room their stink was a more effective weapon than the pikes; they would have been far better bringing long shields and short swords. They would realise quickly enough.

“Hostages,” said my master as I reached for the blade on my back.

I let go of the hilt.

And was among the guards. Bare-handed and violent. The unmistakable fleshy crack of a nose being broken followed by a man squealing like a gelded mount came from behind me as my master engaged the pikers. I shoved one pike aside to get in close and drove my elbow into the throat of the man in front of me—not a killing blow but enough to put the man out of action. The second piker, a woman, was off balance, and it was easy enough for me to twist her so she was held in front of me like a shield with my razor-tipped thumbnail at her throat. My master had her piker in a similar embrace. Blood ran down his face and another guard lay unconscious on the floor next to the man I had elbowed in the throat.

“Open the grating,” she shouted to the walls. “Let us go or we will kill these guards.”

The sound of a man laughing came from above, and the reason for the room’s height became clear as murder holes opened in the walls. Each was big enough for a crossbow to be pointed down at the room and eight weapons threatened us with taut bows and stubby little bolts which would pass straight through armour.

“Open the grate. We will leave and your troops will live,” shouted my master.

More laughter.

“I think not,” came a voice. Male, sure of himself, amused.

One, my master. Two, my master …

The twang of crossbows, echoing through the silence like the sound of rocks falling down a cliff face will echo through a quiet wood. Bolts buried themselves in the unconscious guards on the floor in front of us. Laughter from above.

“Together,” hissed my master, and I pulled my guard round so that we hid behind the bodies of our prisoners.

“Let me go, please,” said my guard, her voice shivering like her body. “Aydor doesn’t care about us guards. He’s worse than Dark Ungar and he’ll kill us all if he wants yer.”

“Quiet!” I said and pushed my razor-edged thumb harder against her neck, making the blood flow. I felt warmth on my thigh as her bladder let go in fear.

“Look at them,” came from above. “Cowardly little assassins hiding behind troops brave enough to face death head on like real warriors.”

“Coil’s piss, no,” murmured the guard in my arms.

“Your loyalty will be remembered,” came the voice again.

“No!”

Crossbows spat out bolts and the woman in my arms stiffened and arched in my embrace. One moment she was alive and then, almost magically, a bolt was vibrating in front of my nose like a conduit for life to flee her body.

“Master?” I said. Her guard was spasming as he died, a bolt sticking out of his neck and blood spattering onto the floor. “They are playing with us, Master.”

Laughter from above and the crossbows fired again, thudding bolts into the body in my arms and making me cringe down further behind the corpse. The laughter stopped and a second voice, female, commanding, said something, though I could not make out what it was. Then the woman shouted down to us.

“We only want you, Merela Karn. Lay on the floor and make no move to harm those who come for you or I will have your fellow shot.”

Did something cross my master’s face at hearing her name spoken by a stranger? Was she surprised? Did her dark skin grey slightly in shock? I had never, in all our years together, seen my master shocked. Though I was sure she was known throughout the Tired Lands—Merela Karn, the best of the assassins—few would know her face or that she was a woman.

“Drop the body, Girton,” she said, letting hers fall face down on the tiled and bloody floor. “This is not what it seems.”

As always I did as I was told, though I braced every muscle, waiting for the bite of a bolt which never came.

“Lie on the floor, both of you,” said the male voice from above.

We did as instructed and the room was suddenly buzzing with guards. I took a few kicks to the ribs, and luckily for the owners of those feet I could not see their faces to mark them for my attention later. We were quickly bound—well enough for amateurs—and hauled to our feet in front of a man as big as any I have seen, though he was as much fat as muscle.

“Shall I take their masks off?” asked a guard to my left.

“No. Take any weapons from them and put them in the cells. Then you can all go and wash their shit off yourselves and forget this ever happened.”

“I think it’s your shit, actually,” I said. My master stared at the floor, shaking her head, and the man backhanded me across the face. It was a poor blow. Children have hurt me more with harsh words.

“You should remember,” he said, “we don’t need you; we only need her.”

Before I could reply bags were put over our heads for a swift, dark and rough trip to the cells. Five hundred paces against the clock walking across stone. Turn left and twenty paces across thick carpet. Down two sets of spiral stairs into a place that stinks of human misery.

Dungeons are usually full of the flotsam of humanity, but this one sounded empty of prisoners apart from my master and I. We were placed in filthy cells, still tied though the bonds did not hold me long. Once free I removed the sack from my head and coughed out a wire I had half swallowed and had been holding in my gullet. It was a simple job to get my arm through the barred window of my door and pick the lock. Outside was a surprisingly wide area with a table, chairs and braziers, cold now. I tiptoed to my master’s cell door.

“Master, I am out.”

“Well done, Girton, but go back to your cell,” she said softly. “Be calm. Wait.”

I stood before the door of her cell for a moment. An assassin cannot expect much mercy once captured. A blood gibbet or maybe a public dissection. Something drawn out and painful always awaited us if we were caught, unless another assassin got to us first—my master says the loose association that makes up the Open Circle guards its secrets jealously. It would have been easy enough for me to slip into the castle proper and find some servant. I could take his clothes and become anonymous and from there I could escape out into the country. I knew the assassins’ scratch language and could find the drop boxes to pick up work. Many would have done that in my situation.

But my master had told me to go back to my cell and wait, so I did. I locked the door behind me and slipped my sack and bonds back on. I imagined a circle filled with air, then let the top quarter of the circle open and breathed the air out. I let go of fear and became nothing but an instrument, a weapon.

I waited.

“One, my master. Two, my master. Three, my master …”

I was at twelve thousand nine hundred my-masters.

The man that came for me did not even glance through the bars to check on me before coming in, which made me sure he must be one of the blessed. Few others in the Tired Lands are so careless, or sure, of their lives.

“So,” he said, standing in the door and blocking the meagre light with his bulk, “still here, assassin?” I said nothing. Nothing is always the best way to go. It is especially infuriating for the blessed, who expect the world to jump at their whims. “I asked you a question,” he said. I still said nothing and would continue to unless they chose to torture me. Then I would say an awful lot of words while still saying nothing.

The man took another step forward, placing his booted feet carefully to avoid the fi

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...