- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

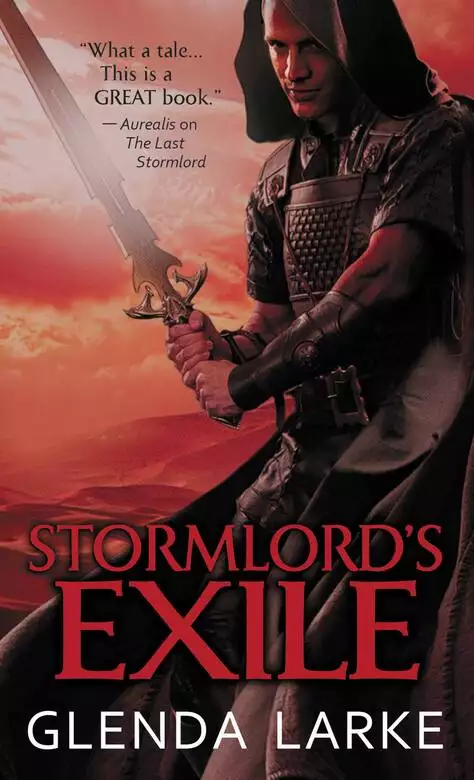

Synopsis

Shale is finally free from his greatest enemy. But now, he is responsible for bringing life-giving rain to all the people of the Quartern. He must stretch his powers to the limit or his people will die-if they don't meet a nomad's blade first. And while Shale's own highlords and waterpriests plot against him, his Reduner brother plots his revenge. Terelle is Shale's secret weapon, covertly boosting his powers with her own mystical abilities. But she is compelled by the strange magic of her people and will one day have to leave Shale's side. No one knows what waits for her across the desert, but her people gave the Quartern its first Stormlord and they may save Shale and his people once again-or lead them to their doom. This is the final volume of the epic Stormlord series.

Release date: August 1, 2011

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 700

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Stormlord's Exile

Glenda Larke

Qanatend City

Qanatend Hall, Level Two

Lord Jasper Bloodstone stood at the window of Qanatend’s stormquest room. His eyes were closed, his mind focused, his body

tense. He ignored the feel of small amounts of water on the steep slopes of the devastated city below, and scattered across

the plains beyond the walls, and concentrated instead on the larger mass he had created.

When he opened his eyes, it was to gaze through the open shutters towards the peaks of the Warthago Range. A distant billow

of dark cloud was a blotch on the blue, like the smudge of a god’s thumb.

The strain eased out of his shoulders and his hands uncurled. Silly to tense up like that, but this cloud had been brought

a long way from the sea. His toughest stormshift ever. He glanced back at the waterpainting on the table behind him, then

again at the scene outside; they were identical. “We did it,” he said. Already someone in the streets below had spotted the

cloud. He heard them calling out, drawing attention to it, followed by joyful laughter.

“More you than me.” Terelle came up behind him to massage his shoulders, easing away the knots, the tenderness in her touch

a balm to his worries. “Without you, my waterpainting would go horribly wrong, and you know it.”

She sounded tired, and he was reminded how much shuffling up exhausted her. How long would they be able to continue to bring

water to the whole Quartern? Two people, supplying everyone? It was impossible! “Why don’t you rest for a bit,” he suggested,

indicating the sofa in front of the fireplace at the other end of the room, “while I get this rain where I want it?”

“Mm. I think I will,” she said. She removed the painting from the paint tray, crumpling it in her hands. “Who’s getting the

water?”

“Golderrun. It’s one of the far northern dunes.”

He watched as she walked to the other end of the long room to throw the ruin of the painting into the empty fireplace. Using

the contents of the tinderbox on the mantelpiece, she set fire to it. The paint curled, then crackled and sputtered, burning

with rainbow colours as the resin within caught fire. He wondered if it assaulted her artistic soul to destroy her own creation,

even though they’d agreed it was necessary.

“I wish I could just acknowl—” he began.

She silenced him with a gesture. “We’ve said it all before.”

“You have, anyway.”

“I’m a terrible scold.”

People must have confidence in their stormlord, she’d said. Better they don’t know about me, not yet. All true, but to take sole credit for something they did together just felt… rotten.

“Wake me when you’ve finished,” she said, and sank down out of sight on the sofa. She was asleep almost immediately.

Turning to his task of moving the rain-laden cloud, he concentrated on keeping it together on its passage over the dunes.

Pebblered first, then Widowcrest, Wrecker, Sand-singer… He worked on, but was interrupted long before the storm reached Golderrun.

Someone knocked at the door with the imperious rapping of a person who did not intend to be denied entry. Jerked away from

his focus, he almost lost his hold on the water vapour. Cursing under his breath, he halted the movement of the cloud.

He didn’t need to open the door to know who was on the other side, or to know they were all people of power: Iani Potch, now

Highlord of Scarcleft, Ouina, who was Highlord of Breakaway, and two other rainlords, both priests from other Scarpen cities.

Finally, worst of all, Basalt. He called himself Lord Gold now, even though the Council of Waterpriests had not yet confirmed

him as the Quartern Sunpriest.

Pedeshit, how he loathed that sanctimonious hypocrite. You sun-fried idiot, Jasper. You forgot to bar the door.

Terelle popped up to peer over the back of the sofa. She blinked sleepily at him, eyebrows raised in query. He shook his head

at her and indicated she should stay out of sight. Eyes widening, she ducked down.

He steeled himself for what was to come. In theory, as a stormlord and their only potential Cloudmaster, he outranked them all. In practice, they were all wealthy Scarpen nobility

who were twice his age—while a few short years ago he’d been Shale Flint, Gibber grubber and waterless settle brat. Their

respect for him was patchy.

Lord Gold didn’t wait for him to answer the door but marched in, his priests and the two highlords trailing behind.

“You wanted to see me?” he asked, barely polite. “I’m stormshifting at the moment. Can’t it wait?”

Basalt flushed purple. “No, it cannot!” he roared. “Do you think we can’t sense what you’re doing?”

“You’re all rainlords, so I’m sure you can. But why should my stormshifting bother you?”

“You’re sending water into the Red Quarter.”

Jasper’s mouth went dry. So that was it. “Yes. That’s my duty, as Cloudmaster.”

“You aren’t the Cloudmaster yet, you sandworm!”

“There aren’t exactly any other contenders for the position.”

“And I doubt your piety, even though you call yourself Bloodstone and wear the Martyr’s Stone as if you have a right to it!”

Jasper’s fingers went to the greenstone pendant around his neck. Flecked with red, such stones were said by the pious to be

stained with Ash Gridelin’s blood. This one he’d found himself.

His baby sister, Citrine, had clutched it as she died…

“My lords, please,” one of the waterpriests said, his tone placating. “That’s not the issue here.”

Basalt turned his cold stare on the man, who faltered. Iani stepped between the priests to speak, his palsied hand trembling like a sand dancer in a mirage, his lip weeping dribble.

Oh, sandhells, Jasper thought, steeling himself to meet the misery in the man’s eyes.

“Jasper, look around you at what was done to this city,” Iani said, pulling him to the window. “Where are the people? Where

are the children? Where’s my Moiqa?” The last question he answered himself, chin quivering. “They nailed her to the gate while

she was alive. Did you know that? Her blood is still there, staining the wood. You can see it. Kaneth carried her remains

up to the House of the Dead…” His voice trailed away. The tremor in his hand began to shake his body.

He swallowed the bile that rose in his gorge. “Iani, I am truly sorry, but—”

“How can you send those murdering red bastards water? How can you!”

His anguish made Jasper wince.

Lord Ouina took up the argument where Iani left off, her anger roiling behind the glint of her eyes and the contempt of her

tone. “They’ll think us weak, you sand-wit. They’ll send their armsmen after us all over again. Their sunblighted army wrecked

our tunnels and maintenance shafts, so why not make them thirst? Have you baked your brains too long in the sun? Do you want them to come back again and take whatever we have left? The next time it could be my city that suffers.”

“Not all Reduners are coloured with the same dust,” he protested. “They didn’t all support Sandmaster Davim in the past and

they don’t all support Sandmaster Ravard now. Would you have them all thirst, even their children, because some among them

are murderers?”

“Yes!” Iani’s dribble spattered them both as he shook an agitated finger. “If they’d been kept busy hunting water before,

they would never have had time to attack us. Qanatend would not have fallen, nor Breccia either. Moiqa would still be alive,

and Highlord Nealrith and Cloudmaster Granthon.” He dabbed at the spittle running from his permanently sagging lip.

“If I cut their water, they’ll steal more from our cisterns,” Jasper replied. “Then they’ll come and batter at our gates.”

“No they won’t,” Basalt said, “because now we are the victors. We should assert our strength and beat them into the ground, the godless heathens that they are.”

“I thought the problem you had with them was that they had too many gods,” Jasper said mildly and then berated himself. Being facetious might be satisfying, but it was only going to make Basalt

hate him all the more. He hurried on. “If I cut their water, it’ll be those who support us who suffer first and most. My lords,

please, you’re wasting your time. The moment we think it’s all right for Reduner children to die by our actions because they

are Reduner, we lose our own humanity. I won’t do it.”

“Children grow up,” Ouina said. “Reduner children become the Davims and Ravards of this world.”

“It’s because of Ravard, isn’t it?” Basalt glared at Jasper, his anger barely under control. “That’s why you continue to water

the dunes. Because he’s your brother. Have your family ties warped your judgement?”

Jasper’s eyebrows shot up, his astonishment genuine. “You’re accusing me of being a traitor?” The surprise was followed by

a stab of fear. Basalt was a powerful man, soon perhaps to be even more so. He needed to be careful, yet resolute. Sunblast it, that’s not easy. Basalt was now in full spate like a rush down a drywash. Damn whoever told him Ravard was my brother. He had no idea who it could have been; a number of armsmen could have heard the tail end of his conversation with Mica during

the battle for the mother cistern.

“My waterpriests saw you talking to Ravard during the battle,” Basalt said. “Talking! When you should have been killing him. Maybe Lord Kaneth is hand in hand with you on this too—didn’t he let the defeated Reduners ride by the walls of this

very city without molesting them? And we know why, don’t we? Lord Ryka persuaded him. Because she was sharing Ravard’s bed!”

His reasoning was so outrageous, Jasper laughed.

“That’s enough!” It was Iani who intervened. “Are you shrivelled, Basalt? If it hadn’t been for Lord Jasper, there wouldn’t have been a victory. If it hadn’t been for Lord Kaneth, Qanatend would still be in Dune Watergatherer’s clutches. Anyway, it was Vara

Redmane who forbade the attack on the defeated dunesmen, not Kaneth.”

“What makes you say that? You weren’t even there.” No hint of conciliation tinged Basalt’s tone. “Now turn that storm around,

Jasper, and put the rain in the Qanatend catchment area.”

In answer, Jasper started the cloud moving again—towards the north. Basalt and Ouina immediately glanced to the window, outrage

on their faces.

“You—you—Gibber upstart! How dare you defy a Sunpriest of the one true faith?” Basalt asked.

Jasper hoped the look he gave the Sunpriest was calm and steady, because it certainly wasn’t how he felt. He wanted to slam

his fist into the bastard’s stomach. He wanted to tear off the man’s priestly robes and tell him he wasn’t fit to wear them. And most of all, he wanted to ram the

lies about Mica and Ryka down his throat until he choked on them.

I will never back down on this. Never. And I’ll see you in a waterless hell first.

“The storm goes north,” he said. “Now, if you don’t mind…” He gestured towards the door.

Iani took the hint and ushered the waterpriests out. Basalt and Ouina both stood their ground. Iani hesitated, then shrugged,

saying as he left, “I hope we don’t all live to regret your decision, Jasper, the way we lived to regret Cloudmaster Granthon’s.”

The words were not so much accusatory as genuinely sorrowful.

Which hurts worse than anything Basalt could say. Jasper held the door open and looked pointedly at Basalt and Ouina. “I think we’ve said everything there is to be said,

my lords.”

“Well, I haven’t,” Ouina said. “You’re witless, Jasper. You’d do well to look hard at your friends. Kaneth and Ryka have thrown their

lot in with the Reduners. She always was a lover of all that was red, and sleeping in Ravard’s tent has tipped her over the

edge. Worse, Kaneth has a head injury and thinks he’s some sort of mythical Reduner hero and your friendship with a snuggery

girl of dubious origins is not helping you see things from a proper perspective.” With that, she stalked from the room, her

back rigid with indignation.

Jasper gaped after her. Ryka and Mica? Where did they get that idea? And Kaneth, crazy? He wasn’t crazy; far from it. They’d spoken at length, several times, since

his own Scarpen forces had descended from the Qanatend mother cistern and found Kaneth and Vara already in possession of the city.

Basalt stared at him through narrowed eyes. His hand clutched at the heavy gold sunburst hanging around his neck, symbol of

the Quartern Sunpriest. He held it away from him as if it was emanating rays of holiness from its metallic heart towards Jasper.

“A warning, Bloodstone. I believe you’ve been influenced by evil ideas from the east, and I will battle to wrest you away

from wrongdoing. Your duty is to men and women of the one true faith.” Those words said, he kissed the sunburst and marched

from the room, his embroidered robes sweeping the flagstones behind him.

Jasper closed the door with a sigh. “You can sit up now,” he said.

“Am I the evil influence from the east?” Terelle asked. She looked shaken.

“Probably. Don’t take any notice of him.”

“He scares me.”

He flung himself down on the sofa beside her. “He can’t hurt us. He can just make things withering irksome.” But if that’s all, why does he worry the innards out of me? “I don’t understand where this silly idea about Lord Ryka and Ravard comes from, though.”

She didn’t reply.

“It’s so ridiculous.”

“Shale,” she said, and then stopped.

He turned his head to look at her, rejecting all her silence said. “No. I don’t believe it.”

“Kaneth’s men, the ones who were slaves—they talk.”

It can’t be true. Ryka’s a good ten years older than he is. She’s a rainlord. Anyway, he wouldn’t do that. Not Mica.

But Terelle would never say anything unless it was true…

“Shale, she was a slave. Kaneth was too hurt to help her. She stayed for him, and the only way a slave gets to stay alive

is to do what they’re told.”

Appalled, the pain more than he could bear, he jumped to his feet and strode to the window, to lean on the sill and drag in

the air as if his lungs were starving. This can’t be right. If it is, I don’t want to know it. I don’t want to think of Ryka and—Oh, weeping shit, how could he?

Deep, calming breaths.

“Don’t forget the cloud,” she said.

Terelle, ever prosaic and practical. He’d forgotten it. Cursing under his breath, he located it again and had to work to pull

the teased edges inwards. She watched him, troubled.

He wanted to say loving things, but—convinced they would sound silly on his tongue—didn’t give voice to them. All he managed

was a softly spoken, “I don’t know what I will do without you.”

She gave a little nod, as if to tell him she understood, but she looked ill. “It won’t be forever,” she said. “I—excuse me.”

She walked to the door, smiling over her shoulder, but her posture was unnaturally stiff. “Be back in a moment.”

He swore again when she was gone, at himself this time. His careless words had made her think about staying with him instead

of going back to her great-grandfather. That was all it took to make her sick, all it took to make Russet’s waterpainted magic

assert its domination over her. That horrible old man had painted her in Khromatis and the painting was pulling her there

before she was older than his depiction of her.

He dropped his head into his hands. When she’d gone, who would help him to stormshift? They—and the whole of the Quartern—were

in such a mess, and no matter which way he looked, he couldn’t see a way out.

The moment Terelle stepped outside the room and shut the door, she leaned against the wall with her eyes closed. Pain griped

her stomach. She wrapped her arms around her waist and slid down the wall until she was sitting on her heels.

Think about going to Khromatis… Think about going to Russet. You’ll feel better then. You’ll meet him in Samphire as you promised…

“Terelle?”

She opened her eyes to see Feroze Khorash, the Alabaster saltmaster, looking down at her, his pale eyes concerned. “Are ye

all right? Ye’re as pale as my pede.”

She shook her head.

“Russet’s magic making ye ill again?”

She nodded. “I was on my way to the privy.”

He reached down and helped her to her feet. “There’s one just along here, if I remember rightly.” Leaning on him and still

clutching her stomach, she made it just in time.

After throwing up, she rejoined Feroze in the passage. He handed her a kerchief and his water skin. “What happened to make

ye sick?” he asked.

“I just—just wanted to stay with Jasper so badly. It overwhelmed the feeling I have to get to Khromatis.”

“A war inside ye, eh? Nasty. Terelle, our Alabaster forces will be leaving for Samphire soon. Ye could come with us.”

“No, I can’t. I have to complete enough waterpaintings to last Jasper while I’m gone and I must see the inside of the Breccian

stormquest room to do them.”

“Ah. So how long before we see ye in Samphire?”

“A third of a cycle perhaps? No more than half a year, for sure. When I left Russet, he said we had a year to get me to the

place where he painted me.” She handed back his kerchief and water skin. “Thank you. I’m better now.”

“Jasper doesn’t know ye get so sick still, does he?”

She shook her head, more vigorously this time. “And he mustn’t. You mustn’t tell him, Feroze, please. He has so many problems

already. He already worries quite enough about me.”

“Ye must learn not to be yearning too much for what ye cannot yet have.”

They exchanged rueful smiles.

She watched him walk away, a kind man who held an innate sorrow within. As far as she knew, he had no family, no lover. His

life appeared to be governed by his reverence for his God and his loyalty to his land and the Bastion. There must have been

much more to him, but she’d never found it. As he vanished around the corner of the passage, she wondered, not for the first

time, where she’d seen that same shrewd, amused look in another set of pale eyes rimmed with white lashes. Whose?

She couldn’t remember.

An armsman brought Jasper a note from Terelle a little later, to say that she was helping out down in the kitchens and wouldn’t

be back. Without thinking—because thinking would have paralysed him into inaction—he asked the armsman to find Lord Ryka and

ask if she had a moment to spare.

When she arrived a little later, his heart dropped queasily. Both of them had come. Ryka and Kaneth. He unbarred the door,

bracing himself for an embarrassing, distressing conversation.

What am I to say? Sunblast you, Mica! You have made things so withering hideous for everyone. When he thought of his brother forcing a woman like Ryka into bed, he wanted to be sick.

He waved the two rainlords over towards the chairs at the table but didn’t sit himself. “I got your message this morning about

you both wanting to return to the Red Quarter,” he said to Kaneth, postponing the need to bring Mica into the conversation.

“The Scarpen needs all the rainlords it can get. Especially Breccia. With Davim dead, his forces defeated and in retreat,

why go back to the dunes?”

Ryka sat, but Kaneth leaned against the heavy wooden lectern where the map of the northern dunes was unrolled. He was wearing

a sword, and had a dagger thrust into his belt as well. With his scarred head and puckered face, plus his look of tautly curbed

tension, he looked every inch a veteran bladesman before a battle. “If you think Ravard considers himself defeated, you’re

badly mistaken. Ryka knows what he intends.”

“He’ll fight to the bitter end,” she agreed, looking down at her hands. “And he still has the men to do it. You defeated an

army, true, but not all Davim’s drovers were involved. Some of his marauding groups were over in Alabaster and another larger

force was in the northern dunes looking for the rebels. They’ll still be itching to prove themselves. The Reduners may coddle

their bruises for a while, but the war’s not over.”

“Vara wants to return home, obviously,” Kaneth added. “She wouldn’t let me attack Ravard’s defeated men because she hopes

in time they’ll desert to join her. She needs more men, and I have some—ex-slaves with revenge in mind. Better still, I can

recruit more. Men of the dunes, Reduners willing to listen to me because they believe I’m Uthardim reincarnated.”

“But you aren’t. And encouraging them to think you are is dishonest.”

“I’ve never encouraged that. In fact I deny it, and have done so ever since I regained my senses.” He gave a lopsided smile

accompanied by a careless shrug. “But if they continue to believe it despite my denial, I will use that belief to help them.

I’ve never been known for the niceties of my moral philosophy, Jasper.”

Oh, waterless damnation. I’ve lost them both…

“Are you sure you aren’t returning just to exact revenge on Ravard?” he asked. The words almost choked him.

Kaneth exchanged a glance with Ryka. “That’s not my specific aim,” he said after a long pause, “although I wouldn’t mourn

him if it happened, and you shouldn’t either. Mica Flint is dead, and what you have in his place—Sandmaster Ravard—is someone

else again.”

Jasper felt ill. “You’ll goad him into a personal fight, if nothing else.”

“If I can. The Red Quarter needs a new sandmaster, a dunemaster if you like, to lead all the tribes on all the dunes; someone

who regards the Scarpen and its stormlord as an ally, not an enemy. Someone who won’t raid the Alabasters or the Gibber and

who doesn’t hanker after the Time of Random Rain. In other words, someone who is not Sandmaster Ravard. I intend to be that person until such time as a suitable Reduner emerges.” He paused, and tilted his head at Jasper in query. “I can’t imagine that you’d object

to any of this.”

Jasper’s stomach churned. Everything Kaneth said was true and logical. Mica had to be stopped. Somehow. He switched his attention

to Ryka, but was unable, in his embarrassment, to maintain eye contact. “You’re a scholar. You don’t belong on the dunes,

surely.” And Watergiver knows, I need your guidance, Lord Ryka.

“Kaneth, Khedrim and I are a family, and I’ll not have us parted again.” Her reply was firm, allowing no hope she would ever

change. “We’d like to have your blessing, and your aid, too, once you’re back in Breccia. More pedes would be useful, for

example. I’ve made a list.”

A list.

He wanted to laugh, more in derision than amusement. Waterless skies, now I know why Taquar thought I couldn’t rule and stormshift too. How can I make decisions about what to

do, organise a war, rebuild Breccia, arrange for Qanatend to be evacuated, all at the same time? And now Kaneth wants above

all else to kill my brother—and I need to help him do it? There were too many problems, and whatever he did, he was supporting his brother’s defeat and death. Mica, always scared

pissless, who’d nonetheless done his best to help him when Pa had turned on him with irrational savagery. He resisted an impulse

to sink into the nearest chair and bury his head in his hands in maudlin self-pity.

Instead, he squared his shoulders and took a deep breath. “Leave me your list when you go,” he said. “I’ll see what can be

done. But remember, I also have Breccia to consider. What’s left of it. Oh, and Kaneth, why don’t you take Davim’s pede? It was one of those we captured. Burnish—magnificent animal. Can’t hurt you on the dunes to be seen

riding Davim’s mount.”

“Thank you,” Kaneth said, obviously pleased. “If it’s any help, we don’t need storms sent to our rebel camp. The water in

God’s Pellets is permanent. Take some out, it refills.”

“But I sense no touch of water out there, none!”

“It’s encircled by stone hills and the water is actually inside a cave. I guess all that blocks your senses.”

“Ah. Let’s hope that keeps you safe from Ravard’s water sensitives too, then. When do you want to leave?”

“Tomorrow morning. One other thing: Elmar Waggoner, my Breccian armsman. I’m leaving him with you.”

“You are?” Jasper was startled. In the past, when it came to action, the two men had always been inseparable.

“Elmar is not that fond of the dunes. He’s a good man in a fix, though, and a fine fighter.”

“I remember. My gain, then.” He hesitated, then added, “Bear this in mind: Mica was a victim.”

“Perhaps. But he abrogated all rights to be treated as such the moment he threw in his lot with a man like Davim.”

“What choice did he have? Kaneth, he was fourteen, maybe fifteen years old! He’d have been killed if he’d stood up to the

sandmaster.”

“And we’d have been a lot better off if he’d had the guts to do just that. Don’t ask me to pity him, Jasper. Not after what

he did to me and mine.”

He turned on his heel and strode out of the room. Jasper suspected it was either that or throw a punch at his stormlord. With

a grimace of annoyance, he turned to Ryka, but she forestalled anything he might have said.

“Jasper, the choices Mica made back then don’t count any more. He—Ravard—has choices now, choices which could change his direction. Those are the ones that count, and the ones he will be judged on.”

“The ones he’ll die by?”

“If he makes the wrong choices, yes. Do you doubt it? Haven’t you seen the look in Kaneth’s eyes?”

“Did—did he treat you so very badly? He was once a gentle person. It was the war—” He almost took a step backwards when he

saw the look she gave him. Spitting sparks, Terelle would have said. You witless waste of water; where’s your sense? It was the kind of remark Shale might have made, but he wasn’t Shale any more and he should have known better. He did know better.

But oh, it was Mica…

Ryka took a deep breath before she answered. “Did he physically mistreat me? No. In his strange way, he was at times even

kind. But he took away both my liberty and my freedom of choice. He used my child to chain me for his personal use. Yes, while

he was still a lad he was kidnapped and raped and whipped, forced to slit the throat of his best friend in order to save his

own life.”

He stared at her, appalled. “Best friend?”

“Chert, I think he said it was.”

Chert? Oh, weeping shit. Rishan the palmier’s son from Wash Drybone. What the withering spit have you done, Mica? How could you?

Remorseless, she continued. “I know all that, so I can feel compassion. And because I do, Kaneth hates him all the more. I

wish I did hate Ravard; it’d make things a lot easier for both of us. Don’t mistake my compassion for lack of resolve, though.

If Ravard continues down the same path, I’ll see him dead—by my own hand if need be.”

The look in her eyes was as hard as ironstone. Jasper kept quiet.

“At this point in time, his fate is in his own hands. All he needs to do is approach you with a plan for reconciliation, and

his future—and ours—can be different. If he doesn’t, good men will continue to die until one of us wipes him from the face

of the dunes. Either way, Kaneth is right. Mica Flint is dead.”

She added, more kindly, “I’m sorry we have to part this way, Jasper. What your brother did has made it impossible for either

of us to return to Breccia, to serve you as rainlords. Maybe… maybe, one day. But now things are too raw.”

He nodded dumbly, hearing what she did not say: Every time I look at you, I will see Ravard, and remember what he did to me…

Still she did not leave, and he waited, knowing she had something else to say. Ryka always did.

“How long will you be able to keep up the storms?”

“I’m not sure.”

“Terelle told me yesterday she has to leave for a time to settle a family matter in Khromatis.?

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...