- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

As the beautiful illusionist Flame succumbs to the dark spell that taints her soul, the physician Kelwyn Gilfeather discovers that the only way to cure her may be to destroy all magic and change the Isles of Glory forever.

Release date: December 21, 2017

Publisher: Gateway

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

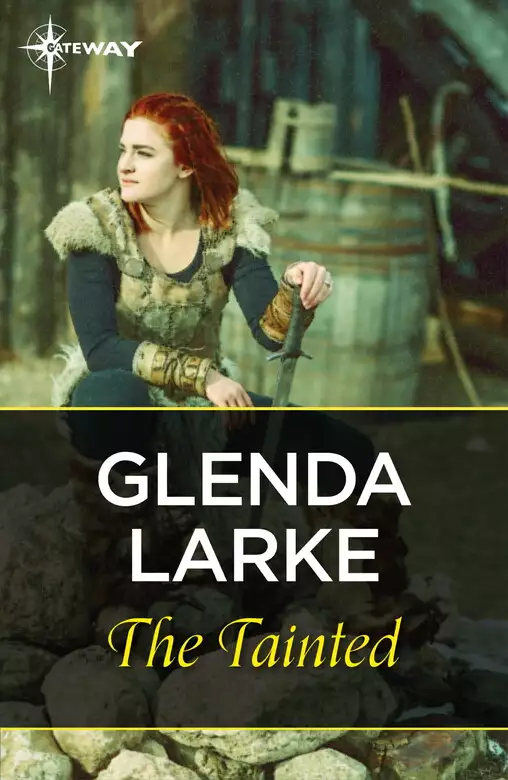

The Tainted

Glenda Larke

Extract from Sketches of the Fall

It wasn’t easy being a girl sometimes. Especially not when you were just sixteen, and hauling in wet fishing nets over a deck slippery with scales and slime. It was even harder when you were also a Dustel Islander, without a proper home, and the only fishing grounds you were permitted to fish were those of the Reefs of Deep Sea.

It isn’t fair, Brawena Waveskimmer thought. The reefs were several days’ sail away from South Sathan Island in the Stragglers where most of the Dustel fisher folk lived, and that meant all the fish had to be cleaned and salted on board before returning to port. Then, of course, they didn’t fetch the higher prices of fresh fish sold by the local Stragglermen.

‘It’s a circle,’ she muttered under her breath. A horrible endless circle keeping them poor. They worked harder than most people and yet earned less, all because they were Dustels, not Stragglermen. Because they were citizens of a place that no longer existed.

‘Watch what you are doing,’ her grandfather growled. ‘You almost lost that fish.’

She hooked the flopping tunny from the deck and dropped it into the holding area. Her grandfather resumed winching in the net. I shouldn’t be doing this at all, she thought resentfully. It’s a man’s work. If only Da hadn’t drowned at sea. If only I had brothers instead of a pack of sisters.

For that matter, if only Morthred hadn’t sunk the Dustel Islands beneath the sea almost a hundred years ago…

She’d heard the story often enough. Her grandfather’s father was alive then. From the deck of the family fishing boat, he’d actually seen the distant islands sink beneath the horizon. No one had believed it at first. The fishermen had pulled up their nets and set sail for Arutha Port, expecting the islands to appear out of a sea mist any moment—but they weren’t there to find any more. A couple of shocked Awarefolk clung to the wooden wreckage of someone’s home, now gently bobbing in an expanse of floating debris that stretched for miles in all directions. There were birds…disoriented birds everywhere, flying aimlessly, keening their distress. Among them—although her great-grandfather had not known it just then—were all that remained of the non-Aware citizenry of the port. Many of them flew clumsily down to his boat, calling and crying out to him to help them, save them, didn’t he know who they were… Look here, I’m your cousin, Etherald; look at me, I’m your neighbour Lirabeth… But he didn’t know what they were saying. He hadn’t understood then what they were trying to tell him as they came and settled on the mast of the boat, as they crowded the rigging and clung to the gunwale. They chirped and chittered and cried, and they had made no more sense to themselves than they had to him.

No one understood until much, much later. And now it was the best kept secret of the Isles of Glory, kept by all people who claimed Dustel ancestry: the knowledge that their closest relatives were birds with human intelligence. Not the same ones who had suffered the spell, of course, but their descendants. Small, dark birds with a purplish sheen and a maroon band across their breasts, who spoke their own avian language and yet could understand human speech.

Brawena took the last fish out of the net and straightened her aching back. And saw something that shouldn’t have been.

‘Grandda, what’s that?’

The old man stared out in the direction of her gaze. There was a disturbance in the water, a sudden swirl about fifty paces astern. Even as they watched, it began to spread, sending out tentacles of movement through a gentle swell.

‘Must be a school of something,’ he said gleefully. ‘Get the foresail up, lass.’

She moved to do his bidding as he raised the anchor, but she kept an eye on the swirling water while she worked. ‘It doesn’t look like fish,’ she said, as he edged the boat around and the canvas gathered up a puff of wind. ‘It can’t be a whale…or a sea-dragon, can it?’

He frowned and eased off on the tiller so that the canvas hung limply. There was something odd about the disturbance. It looked almost as if the water was boiling, or as if some great leviathan of the deep was pushing its way upwards. The water was heaving. A school of frightened fish swept past the boat and for once neither Brawena nor her grandfather took any notice.

‘I think we’d better leave,’ the old man said suddenly. ‘Get the mainsail up, girl, and quickly.’ The urgency of his tone made Brawena dive for the halyard without taking time to ask why. It was one thing to suggest leaving, of course, and quite another to do so when there was only the lightest of breezes. Until the underwater upheaval, the ocean had been almost flat, and the wind playfully fickle, dancing up ripples here and there, then fading into stillness.

Once the sail was raised, Brawena looked back over the stern.

In the middle of the boiling ocean, something thrust its way upwards like a huge skeletal hand reaching for the sky. Water poured away from it, leaving the bare fingers standing red and naked and shining in the sun. She still hadn’t had time to make sense of that when the sea surface ripped open in a jagged line, as if a giant had torn it asunder from underneath. Everywhere she looked shapes reached up out of the water, shedding the sea in torrents. A school of porpoises leapt away in panicked curves of silver and grey.

A gust hit the sails of the boat, and it heeled sharply. Brawena clutched the gunwale, her mouth dropping open as she gazed wide-eyed on the scene astern. Scarlet trunks, leafless ebony trees, round sea-weeded knobs, pillars of purple and green and gold sprang from beneath the ocean and were pushed skywards. Waterfalls cascaded foam from between them all as water rushed back to the sea.

And still the things from the depths pushed up from the sea floor. The scarlet and black trees—corals she realised—were now ten paces up in the air and still rising, thrust upwards on a base of seaweed-covered rocks and sand. The welling up of water came closer and closer to the boat, as more reefs appeared from beneath the waves. The last mass to appear, covered in weed and oyster shells and anemones, seemed strangely angular, the corners too regular to be natural. There were towers and steps and walls of rock, lines of them. Streets of coral-encrusted buildings. Fish caught in the ruts of bygone roadways flopped and gulped, hot and helpless.

Doomed, she thought, and sadness cut through her like a flensing knife. All that life, it’s all doomed in the sunlight…

She clutched at her grandfather.

He wiped away tears and whispered, ‘Child, it’s happened. It’s finally happened.’ Their boat, caught on the outward flow of waves, slid away from the broiling seas.

‘What has?’ she whispered, knowing she ought to be able to make sense of this, but shocked instead into a state from which sense had vanished.

‘Don’t you understand, lass?’ He waved at the land behind them. ‘Those are the Dustel Isles!’ His face glowed with joy even as his tears runnelled down the creases of his cheeks. ‘There was once a town, right there—see the buildings? Perhaps it was even Port Arutha. Brawena, Morthred is dead! We can go home again…’

—Postseaward, 1797.

Anyara isi Teron: Journal entry

23 / 1st Double / 1794

As I pen this in my cabin aboard the R.V. Seadrift, I find myself wondering: is this really I, Anyara isi Teron, here on board a ship bound for the Isles of Glory? Freckled, prosaic, undistinguished Anyara, embarking on an adventure most men could only dream about—it’s not possible, surely! And yet I, an unmarried woman, find myself untrammelled by family, with the shores of Kells rapidly dwindling on the horizon and empty ocean ahead…adventure indeed.

True, there is Sister Lescalles isi God sitting opposite me as I write, reading her religious tracts and praying for my godless soul. My parents would only countenance my journey if I was chaperoned by a senior missionary sister of the Order of Aetherial Nuns, and Lescalles is nothing if not senior. She must be close to seventy. Far too old, surely, to embark on a journey like this one, yet her eyes shine with the zeal of a proselytiser as she contemplates the Glorian souls she will save.

And true, too, somewhere on board is Shor iso Fabold, who is charged with ‘keeping an eye on Anyara to make sure she comes to no harm in this madcap venture of hers’. Poor Shor. He has grown to hate me, and we would avoid each other if we could. But alas, how is it possible to avoid someone on a ship smaller than our townhouse garden back in Postseaward? We dine at the same table, share the same companionways and walk the same decks. We nod politely and bid one another good morrow, but underneath he seethes. To think there was a time I would have wed him, had he asked, and been joyous in the union.

That was before he found out I was determined to set sail for the Glory Isles. Before he found out I was reading copies of all the translations of his conversations with Blaze Halfbreed and Kelwyn Gilfeather. (I asked the young clerk who worked in the library of the National Society for the Study of non-Kellish Peoples to secretly copy them for me; in return I promised to procure him a job as librarian on my cousin’s country estate. We both kept our side of the bargain. There, I have written down my wickedness…I am quite without conscience.)

There is an irony in the antipathy with which Shor now regards me, of course. The seeds of all he has come to dislike about me were sown by what I learned of Blaze Halfbreed, and it was he who—by his interviews with Blaze—unwittingly showed me that other possible future. Through her, I learned there can be another life for a woman, a life beyond that of obedience and piety and ‘taking a turn around the garden’ for fresh air and health. Poor Shor indeed. He admired both my intelligence and my independence, but ended by hating my exercising of either. The idea that I have obtained official royal sanction of my journey—I am bidden by Her Excellency the Protectoress to report to her on the position of Glorian women in Isles society—is anathema to him.

And so we tread carefully around each other, and pretend indifference to our shared past. It is awkward, but I have no regrets for what I have done. My deception was regrettable, I know, but he would not let me read the text of his conversations with Blaze, so what was I to do? He titillated my imagination with his stories of her, but tried to hide her actual words from me. Am I the brazen jade he named me in our final argument? Probably. But I will let nothing stop me from searching for this woman, born half a world away from me, whose life has been so different from my cosseted existence—and yet who has the power to speak to my soul.

I have more of the copied conversations with me on board: I had not time to read them all before we left. I have yet to find out if Ruarth Windrider—whose impossible love for Flame, the Castlemaid of Cirkase, brought tears to my eyes—survived the death of the dunmagicker Morthred. I desperately want to know if Flame rose above her contamination with dunmagic. Did she give birth to the child, Morthred’s heir, who was the source of her contamination? Did Blaze ever marry, and if so, then whom? I want to know just what this mysterious Change is that Blaze has spoken of so often. I want to know what happened to the ghemphs: why and how they vanished. Shor told me Glorians were still receiving citizenship tattoos from the ghemphs as late as the year the first Kellish explorers arrived, 1780, but then they abruptly stopped. He said he never found a child born later than that who had an ear tattoo.

And, most importantly of all, I want to know what happened to magic. Is Shor right and it was all a figment of the collective imagination born of superstition: some kind of mass hallucination experienced by the Glorian peoples?

I could probably find an answer to most of these questions were I to read the rest of the copied documents I have. From where I sit, if I glance over to the wall under the porthole, I see my two sea chests, now stacked on top of each other to make a chest-of-drawers with polished brass handles; all I have to do is open that top drawer and the documents are there for the reading. Yet I hesitate to hurry through the papers. I have months ahead of me, and I must ration my reading. Perhaps this evening I will dip into the first of the papers. Just a few.

Right now Lescalles is restless. Here we are, barely two days out of port, and already I know her as well as I know the freckles on my own nose. I shall put her out of her misery and suggest a turn about the deck…

I dug my claws into the rope of the rigging and tried to calm my chaotic breathing. I was safe now, surely, no matter what happened. As long as I held on.

I took a deep breath, aware I was shivering. Pure funk, of course, not cold. When you’re covered with feathers, you don’t feel the cold much, and even the stiff breeze that made the shrouds strain against the mast of the Amiable could not bring a chill to my skin.

The truth was that the terror I felt went so deep it could have been part of my soul. I had just flown down from the top of the stack that towered five hundred paces high above the surface of the ocean. Five hundred human paces, that is. I hadn’t followed the path, either. I had arrowed down like a gannet towards the sea, driving myself lower with every beat of my wings. All the while, I was thinking: if Kelwyn Gilfeather kills Morthred right now, then I might end up with my feathers splattered all over the ocean. No, not feathers. Skin and flesh. I would be a very dead human, without ever knowing what it was like to be human.

To be quite honest, the closer Morthred’s death came, the less I believed it would not affect the Dustel birds. The less I believed we were immune because we were born ensorcelled…

But apparently Kelwyn hesitated to kill the dunmaster, and I lived a little longer. As I sat there on the rigging I spared a moment to wonder what scared me the most: that Morthred would die—or that he wouldn’t. I couldn’t make up my mind. Both possibilities were entangled with horrors. I looked down from my perch and ruffled my feathers in an attempt to calm my panic. Pull yourself together, Ruarth! Think.

Four people stood on the deck directly below me. None had any idea I was there.

Flame was one of them. She was dressed as she had been while watching the race, in a green gown. The dangling ends of a heavily beaded sash kept the skirt from lifting in the wind. I might have thought it lovely had I not known it’d been given to her by Morthred, a gift from among his plundered riches. Morthred, who had raped her. Who had contaminated her, defiled her, tried to mould her to his image of evil.

She spoke to two sylv women, both subverted now to dunmagickers, and the Amiable’s captain, a one-armed Spatterman I knew only as Kayed. His forearm was missing, something he had in common with Flame, although his was gone from below the elbow, unlike Flame’s which had been amputated above the joint. I suspected he was a foul-mouthed bastard at the best of times; now that he was imprisoned with dunmagic he almost foamed with righteous rage, but powers that were not his kept his mouth from uttering the words he wanted to say.

I switched my attention back to the two sylv women. They were the lucky ones among Morthred’s subverted acolytes; they had not taken part in the stack race because neither of them could swim. All those who had participated were probably dead by now, or at the very least doomed.

‘I don’t care what you think,’ Flame was saying to them. ‘We are leaving now.’ She turned to Kayed. ‘Cast off.’

‘We haven’t paid the port fees—’ the man began. I pitied him; the brown-red of dunmagic played over his shoulders and torso, imprisoning his will with its chains. He could not do much with his rage; every time he tried to resist, the dun-coloured ropes of magic that were looped over his body well nigh strangled him. On our journey from Porth to Xolchas Stacks aboard his stolen vessel, his resistance had almost killed him several times.

‘They won’t see us go, and don’t question my orders or I’ll toss you overboard,’ Flame snapped. Dunmagic rippled outwards from her, foul with coercion. This time the man didn’t hesitate. He turned to his crew and gave the orders to sail. I dithered, trying to think of a miracle that would stop our departure from Xolchasport. I glanced upwards to the top of the stack. Cliffs loured over the harbour, a lethal rockface that could sheer away at any time. Seabirds inhabited every ledge; large and brutal in their language, argumentative by inclination, they were as foreign and incomprehensible to me as fish in the sea.

‘We can’t leave without the Rampartlord,’ the older of the two dunmagickers, a middle-aged woman called Gabania, protested. She’d worked for Syr-sylv Duthrick and the Keeper Council before her subversion to dunmagic.

Flame raised an eyebrow, even though she must have known Gabania was referring to Morthred. ‘Rampartlord?’

‘The dunmaster. Rampartlord of the Dustel Islands. It—it’s the title he prefers.’

Flame snorted. Perhaps she recognised irony. There were no Dustel Isles, thanks to Morthred.

The second dunmagicker, Stracey, waved her hands in agitation. ‘He’ll kill us,’ she whispered.

‘He’s not here, Stracey,’ Flame said and added nastily, ‘but I am. And I will kill you if we don’t leave. Right now.’

Stracey looked at Gabania for leadership and Gabania hesitated, obviously toying with the thought of resistance as she considered her own strengths matched to Flame’s.

‘Don’t do it,’ Flame warned. Then she let the menace in her tone slip away as she added, ‘Listen, this is our chance. Morthred won’t call us back with the force of his will, I promise you. He is going to die any time now and we can go where we will, do what we will. And all the treasure on this ship will be ours…’ I could hear no trace of the Flame Windrider I knew just then. ‘Think of the power we’ll have, Gabania. Dunmagickers, with a ship, and these sailors as slaves, and all the money we’ll ever want. Everything, in fact, that Morthred has amassed over the past few years since his powers returned.’

A flash of hope sparked in the older woman’s voice as the remnants of her independence asserted itself. ‘Morthred’s going to die?’

‘Yes. Those people who tried to rescue me back on Porth—I saw one of them here. I know those people. I know the way they think. They will kill him any minute now, while everyone else is still occupied with the stack race.’

‘Will we—will we be sylv again?’ Stracey asked. She sounded puzzled, as if she didn’t understand her own question.

Flame reached out to cup the girl’s face in her hand. ‘No, sweetie. You won’t. Because you won’t let it happen, will you? You will use you own dunmagic to stay a dunmagicker. Now, go and make sure those fools of sailors obey my orders.’

Obedience to Morthred had made Gabania and Stracey tractable, so they went without further argument. For a moment Flame watched them, then she leant against the railing. I knew what she was doing; I’d seen it often enough. Tendrils of colour floated outwards like a soft mist. Once it would have been silver blue; now it was more a deep lilac colour, and streaked with both silver and reddish-brown. She was going to cover our departure with illusion. It was a form of magic that no longer came so easily to her: it was a sylvtalent rather than a dun skill, and she was losing her sylv.

Above her, I felt ill, with an illness that was lodged more in my mind and heart than in my gut. I had tried to keep my Flame—the gentle, loving Flame—alive, but I really had no idea how to save her. I still didn’t understand her present subversion, any more than Blaze and Kelwyn had last time I’d spoken to them. There was something odd about it. All I could do was hope that once Morthred was dead, it would make a difference. That her own integrity would allow her to fight, to give her a chance.

And above us, in the town of Xolchasbarbican, were the people who might be able to help. Kelwyn Gilfeather, the Sky Plains physician; perhaps there would be something he could do with his medications once Morthred was gone. And the others: Blaze Halfbreed who had proved herself more than a friend; Tor Ryder, the Menod patriarch who would rid the world of magic if he could find a way; Dekan Grinpindillie, the Aware lad from Mekaté—they all wanted to help, but I had no idea how to stop her from sailing away from them and the hope they offered.

I’d assured Flame that there were those who would rescue her, who would ensure she never suffer again the tortures Morthred inflicted on her. She’d listened, I’ll give her that. Then, on the last occasion we spoke at all intimately, she’d held me in the palm of her hand and closed her fingers around my body. Her thumb caressed my throat in a gesture that contained no love, no gentleness, no concern for the fragility of my bones. She raised me to the level of her eyes, only a hand span from her face. ‘I am a dunmagicker,’ she said. ‘I want nothing else.’

‘Flame—’ I began.

‘Lyssal,’ she hissed, reverting to her real name. ‘Call me Lyssal.’ The thumb moved in a circle at my throat. ‘I can crush you, Ruarth, as easily as a thrush crushes a snail shell.’ She tightened her fingers until I found breathing an effort. ‘So simple. So very simple to do.’

I kept absolutely still, feeling the extremity of my danger through the sweat of her fingers. This was not Flame. This was a stranger who wanted to snap my neck.

What held her back? Some remnant of the woman that still dwelled within—the Flame I had known since I was a fledgling living in the crannies of the walls of the palace of Cirkasecastle and she was the lonely, neglected Castlemaid, heir to a throne, who had fed the birds on her window sill?

We were in the Lord’s House in Xolchasbarbican at the time and, perhaps luckily for me, a servant of the Barbicanlord had entered the room just then. Lyssal whispered in my ear, ‘If you ever come near me again I will kill you, Ruarth. Be warned.’ And she opened her fingers, allowing me my freedom.

I had not dared to test her promise. I’d not come near her again, choosing merely to watch from a distance. I continued to speak to her in gesture and whistle, but mostly she did not listen. That was easy enough; if she looked away, she missed all the visual clues and therefore most of what I said. And now, as I looked down from the rigging with my loneliness dragging at me like a yoke around my neck, I could not think of any way to persuade her to stay.

The crew were already hauling in the hawsers. Sailors manned the winches and sails shivered upwards. No one on the wharf as much as looked our way as illusion swirled about us, suffocating, unnatural.

Once, I’d gloried in the sylvpower Flame manifested. Once, I’d seen it as something of value. It had given her a chance to escape the unpleasantness of the fate her father and the Breth Bastionlord contrived for her, backed by the Keepers of The Hub: as a brood mare for a perverted tyrant. The Council of the Keeper Isles had wanted the Bastionlord to sell them his saltpetre and they’d put pressure on the Cirkase Castlelord to give the ruler of Breth what he wanted in return. Lyssal. It was an evil compact, with Flame no more than bait for the sharks. Her sylvtalents had saved her then.

But now, now it was her sylvpower that made her vulnerable to dunmagic subversion. Perhaps, I thought, Tor Ryder is right. The Isles would be better without any magic at all. Perhaps it is an evil thing. Not innately evil—not even Tor thought that—but evil because of the failings of mankind. There are too many people who use sylvmagic in ways that are either petty and trivial, or monstrous. All power, Tor said to me once, should have checks and balances to keep it harnessed. Yet no one can bridle the sylvs of the Keeper Isles.

He should have added: except a dunmaster. Morthred had done a fine job of bridling sylvpower.

A flock of birds flew across the wharf towards me, twittering as they came, each call distinct to my ears. They were saying their names, over and over—it meant nothing; it was just a way we Dustel birds had of keeping in touch as we flew in a flock. Of saying to others in the air about us, ‘I’m right here, by your wing tip.’ They were heading towards me, doubtless to give me news of what was happening in the upper town of Xolchasbarbican. I felt a flooding relief: I would be able to pass them a message for Blaze and Gilfeather.

And then the world lurched.

I have no other way to describe it. Everything around me dropped away, leaving my stomach somewhere above and my mind in limbo.

My last glimpse through avian eyes appalled me: I saw birds turn into people and fall out of the sky. And then Morthred’s death swept over me, changing every particle of my body into something else.

For a moment I truly died.

There was darkness, a blackness so blanketing it contained only emptiness. Silence, an external muteness so intense I could hear the internal sounds of my body being ripped apart, particle by particle. Numbness, a lack of stimulation so pervading I felt I had no body. I thought: so this is what it is like to die.

I plunged into the darkness, into the silence, into the numbness, into that total deprivation. When I emerged, I was on the other side of death, in a life about which I understood nothing.

Everything had changed. Everything. All my senses had been altered so much I couldn’t…well, I couldn’t make sense of them.

I was Ruarth Windrider and I was human.

Well, I’ve read the note you brought from Kelwyn Gilfeather. He says I should talk to you, and so I will, although I can’t say I regard you Kellish foreigners with any particular kindness. You are all far too fond of pontificating on Glorian deficiencies for my liking. I hear tell there are some among you who want to bring in your priests to convert the Glory Isles to your religion; I even hear talk of a fleet of missionaries. What makes you think your beliefs are better than ours? Take my advice, and don’t try it here on Tenkor. We are Menod on these six islands of the Hub Race. Always have been, always will be.

Doubtless you have heard that we of the Tideriders’ Guild don’t always see eye to eye with the Menod Patriarchy, and that is true enough. We are the temporal power on the islands of Tenkor and they are the spiritual power here. In fact, throughout much of the Glory Isles. We often have our differences, but don’t make the mistake of thinking you can divide us; you can’t. When threatened from outside we unite, just as we did back in 1742 at the beginning of the Change.

Guild and Patriarchy affairs have always been entangled so tight it would be hard to separate them anyway. Did you know Menod success in spreading the word of God stems from our Guild treasury? That’s right, Menod wealth came from the longboatmen and tiderunner riders of the Hub Race. Still does. Without us, the Menod Patriarchy would be nothing. Of course, our support is freely given; we of the Guild are mostly Menod, after all.

Me? Oh…I’ve never been much of a one for religious observances myself. I attend the festival services, twice a year, and make my obeisance at the Blessing of the Whale-King, but no more than that. I was born full of sin, riddled through with evil, my father used to tell me, and then he’d beat me for my lack of piety. My reluctance to demonstrate religious devotion should not have puzzled him—for years he refused to allow me to enter the Worship House, saying that until I could control my wickedness I was not allowed the blessings of God. How he thought that would encourage piety instead of having the opposite effect, I have no idea. But then, my father always was a twisted soul.

However, I am still a Menod; do not doubt it. Just not a very good one.

Sorry, I’m rambling. You want me to start with the day the people fell out of the sky? Very well. I’ll begin there. It’s appropriate anyway, because to me that was the day the Change began. Blaze will tell you it started back on Gorthan Spit, but that’s her story, not mine. To me, it began on the day of the Fall. We called it that, hoping an innocuous word would take away the horror; it didn’t. It still doesn’t.

The Fall was a watershed between the old world that went before and the world of the Change thereafter. On Tenkor, we always date events from then. ‘Oh, that happened two years before the Fall’ or ‘Oh, he died about ten years after the Fall’. Most of all, it was just a horror so intense no one who lived through it would ever forget.

I remember everything about it as if it happened yesterday, instead of fifty years ago.

I was down on the waterfront in Tenkorharbour, at the Guild Hall where we tideriders all had rooms. I was idling around, waiting for my turn of duty. I should have been using the time to study—I had a final astronomy examination the next week, followed by a string of papers on rider ethics, wave anomalies, tidal subtleties, and the new sand configurations of the Hub Race. If I didn’t pass them all, I’d have to wait another year before retaking, and that would mean one more year before I had

It wasn’t easy being a girl sometimes. Especially not when you were just sixteen, and hauling in wet fishing nets over a deck slippery with scales and slime. It was even harder when you were also a Dustel Islander, without a proper home, and the only fishing grounds you were permitted to fish were those of the Reefs of Deep Sea.

It isn’t fair, Brawena Waveskimmer thought. The reefs were several days’ sail away from South Sathan Island in the Stragglers where most of the Dustel fisher folk lived, and that meant all the fish had to be cleaned and salted on board before returning to port. Then, of course, they didn’t fetch the higher prices of fresh fish sold by the local Stragglermen.

‘It’s a circle,’ she muttered under her breath. A horrible endless circle keeping them poor. They worked harder than most people and yet earned less, all because they were Dustels, not Stragglermen. Because they were citizens of a place that no longer existed.

‘Watch what you are doing,’ her grandfather growled. ‘You almost lost that fish.’

She hooked the flopping tunny from the deck and dropped it into the holding area. Her grandfather resumed winching in the net. I shouldn’t be doing this at all, she thought resentfully. It’s a man’s work. If only Da hadn’t drowned at sea. If only I had brothers instead of a pack of sisters.

For that matter, if only Morthred hadn’t sunk the Dustel Islands beneath the sea almost a hundred years ago…

She’d heard the story often enough. Her grandfather’s father was alive then. From the deck of the family fishing boat, he’d actually seen the distant islands sink beneath the horizon. No one had believed it at first. The fishermen had pulled up their nets and set sail for Arutha Port, expecting the islands to appear out of a sea mist any moment—but they weren’t there to find any more. A couple of shocked Awarefolk clung to the wooden wreckage of someone’s home, now gently bobbing in an expanse of floating debris that stretched for miles in all directions. There were birds…disoriented birds everywhere, flying aimlessly, keening their distress. Among them—although her great-grandfather had not known it just then—were all that remained of the non-Aware citizenry of the port. Many of them flew clumsily down to his boat, calling and crying out to him to help them, save them, didn’t he know who they were… Look here, I’m your cousin, Etherald; look at me, I’m your neighbour Lirabeth… But he didn’t know what they were saying. He hadn’t understood then what they were trying to tell him as they came and settled on the mast of the boat, as they crowded the rigging and clung to the gunwale. They chirped and chittered and cried, and they had made no more sense to themselves than they had to him.

No one understood until much, much later. And now it was the best kept secret of the Isles of Glory, kept by all people who claimed Dustel ancestry: the knowledge that their closest relatives were birds with human intelligence. Not the same ones who had suffered the spell, of course, but their descendants. Small, dark birds with a purplish sheen and a maroon band across their breasts, who spoke their own avian language and yet could understand human speech.

Brawena took the last fish out of the net and straightened her aching back. And saw something that shouldn’t have been.

‘Grandda, what’s that?’

The old man stared out in the direction of her gaze. There was a disturbance in the water, a sudden swirl about fifty paces astern. Even as they watched, it began to spread, sending out tentacles of movement through a gentle swell.

‘Must be a school of something,’ he said gleefully. ‘Get the foresail up, lass.’

She moved to do his bidding as he raised the anchor, but she kept an eye on the swirling water while she worked. ‘It doesn’t look like fish,’ she said, as he edged the boat around and the canvas gathered up a puff of wind. ‘It can’t be a whale…or a sea-dragon, can it?’

He frowned and eased off on the tiller so that the canvas hung limply. There was something odd about the disturbance. It looked almost as if the water was boiling, or as if some great leviathan of the deep was pushing its way upwards. The water was heaving. A school of frightened fish swept past the boat and for once neither Brawena nor her grandfather took any notice.

‘I think we’d better leave,’ the old man said suddenly. ‘Get the mainsail up, girl, and quickly.’ The urgency of his tone made Brawena dive for the halyard without taking time to ask why. It was one thing to suggest leaving, of course, and quite another to do so when there was only the lightest of breezes. Until the underwater upheaval, the ocean had been almost flat, and the wind playfully fickle, dancing up ripples here and there, then fading into stillness.

Once the sail was raised, Brawena looked back over the stern.

In the middle of the boiling ocean, something thrust its way upwards like a huge skeletal hand reaching for the sky. Water poured away from it, leaving the bare fingers standing red and naked and shining in the sun. She still hadn’t had time to make sense of that when the sea surface ripped open in a jagged line, as if a giant had torn it asunder from underneath. Everywhere she looked shapes reached up out of the water, shedding the sea in torrents. A school of porpoises leapt away in panicked curves of silver and grey.

A gust hit the sails of the boat, and it heeled sharply. Brawena clutched the gunwale, her mouth dropping open as she gazed wide-eyed on the scene astern. Scarlet trunks, leafless ebony trees, round sea-weeded knobs, pillars of purple and green and gold sprang from beneath the ocean and were pushed skywards. Waterfalls cascaded foam from between them all as water rushed back to the sea.

And still the things from the depths pushed up from the sea floor. The scarlet and black trees—corals she realised—were now ten paces up in the air and still rising, thrust upwards on a base of seaweed-covered rocks and sand. The welling up of water came closer and closer to the boat, as more reefs appeared from beneath the waves. The last mass to appear, covered in weed and oyster shells and anemones, seemed strangely angular, the corners too regular to be natural. There were towers and steps and walls of rock, lines of them. Streets of coral-encrusted buildings. Fish caught in the ruts of bygone roadways flopped and gulped, hot and helpless.

Doomed, she thought, and sadness cut through her like a flensing knife. All that life, it’s all doomed in the sunlight…

She clutched at her grandfather.

He wiped away tears and whispered, ‘Child, it’s happened. It’s finally happened.’ Their boat, caught on the outward flow of waves, slid away from the broiling seas.

‘What has?’ she whispered, knowing she ought to be able to make sense of this, but shocked instead into a state from which sense had vanished.

‘Don’t you understand, lass?’ He waved at the land behind them. ‘Those are the Dustel Isles!’ His face glowed with joy even as his tears runnelled down the creases of his cheeks. ‘There was once a town, right there—see the buildings? Perhaps it was even Port Arutha. Brawena, Morthred is dead! We can go home again…’

—Postseaward, 1797.

Anyara isi Teron: Journal entry

23 / 1st Double / 1794

As I pen this in my cabin aboard the R.V. Seadrift, I find myself wondering: is this really I, Anyara isi Teron, here on board a ship bound for the Isles of Glory? Freckled, prosaic, undistinguished Anyara, embarking on an adventure most men could only dream about—it’s not possible, surely! And yet I, an unmarried woman, find myself untrammelled by family, with the shores of Kells rapidly dwindling on the horizon and empty ocean ahead…adventure indeed.

True, there is Sister Lescalles isi God sitting opposite me as I write, reading her religious tracts and praying for my godless soul. My parents would only countenance my journey if I was chaperoned by a senior missionary sister of the Order of Aetherial Nuns, and Lescalles is nothing if not senior. She must be close to seventy. Far too old, surely, to embark on a journey like this one, yet her eyes shine with the zeal of a proselytiser as she contemplates the Glorian souls she will save.

And true, too, somewhere on board is Shor iso Fabold, who is charged with ‘keeping an eye on Anyara to make sure she comes to no harm in this madcap venture of hers’. Poor Shor. He has grown to hate me, and we would avoid each other if we could. But alas, how is it possible to avoid someone on a ship smaller than our townhouse garden back in Postseaward? We dine at the same table, share the same companionways and walk the same decks. We nod politely and bid one another good morrow, but underneath he seethes. To think there was a time I would have wed him, had he asked, and been joyous in the union.

That was before he found out I was determined to set sail for the Glory Isles. Before he found out I was reading copies of all the translations of his conversations with Blaze Halfbreed and Kelwyn Gilfeather. (I asked the young clerk who worked in the library of the National Society for the Study of non-Kellish Peoples to secretly copy them for me; in return I promised to procure him a job as librarian on my cousin’s country estate. We both kept our side of the bargain. There, I have written down my wickedness…I am quite without conscience.)

There is an irony in the antipathy with which Shor now regards me, of course. The seeds of all he has come to dislike about me were sown by what I learned of Blaze Halfbreed, and it was he who—by his interviews with Blaze—unwittingly showed me that other possible future. Through her, I learned there can be another life for a woman, a life beyond that of obedience and piety and ‘taking a turn around the garden’ for fresh air and health. Poor Shor indeed. He admired both my intelligence and my independence, but ended by hating my exercising of either. The idea that I have obtained official royal sanction of my journey—I am bidden by Her Excellency the Protectoress to report to her on the position of Glorian women in Isles society—is anathema to him.

And so we tread carefully around each other, and pretend indifference to our shared past. It is awkward, but I have no regrets for what I have done. My deception was regrettable, I know, but he would not let me read the text of his conversations with Blaze, so what was I to do? He titillated my imagination with his stories of her, but tried to hide her actual words from me. Am I the brazen jade he named me in our final argument? Probably. But I will let nothing stop me from searching for this woman, born half a world away from me, whose life has been so different from my cosseted existence—and yet who has the power to speak to my soul.

I have more of the copied conversations with me on board: I had not time to read them all before we left. I have yet to find out if Ruarth Windrider—whose impossible love for Flame, the Castlemaid of Cirkase, brought tears to my eyes—survived the death of the dunmagicker Morthred. I desperately want to know if Flame rose above her contamination with dunmagic. Did she give birth to the child, Morthred’s heir, who was the source of her contamination? Did Blaze ever marry, and if so, then whom? I want to know just what this mysterious Change is that Blaze has spoken of so often. I want to know what happened to the ghemphs: why and how they vanished. Shor told me Glorians were still receiving citizenship tattoos from the ghemphs as late as the year the first Kellish explorers arrived, 1780, but then they abruptly stopped. He said he never found a child born later than that who had an ear tattoo.

And, most importantly of all, I want to know what happened to magic. Is Shor right and it was all a figment of the collective imagination born of superstition: some kind of mass hallucination experienced by the Glorian peoples?

I could probably find an answer to most of these questions were I to read the rest of the copied documents I have. From where I sit, if I glance over to the wall under the porthole, I see my two sea chests, now stacked on top of each other to make a chest-of-drawers with polished brass handles; all I have to do is open that top drawer and the documents are there for the reading. Yet I hesitate to hurry through the papers. I have months ahead of me, and I must ration my reading. Perhaps this evening I will dip into the first of the papers. Just a few.

Right now Lescalles is restless. Here we are, barely two days out of port, and already I know her as well as I know the freckles on my own nose. I shall put her out of her misery and suggest a turn about the deck…

I dug my claws into the rope of the rigging and tried to calm my chaotic breathing. I was safe now, surely, no matter what happened. As long as I held on.

I took a deep breath, aware I was shivering. Pure funk, of course, not cold. When you’re covered with feathers, you don’t feel the cold much, and even the stiff breeze that made the shrouds strain against the mast of the Amiable could not bring a chill to my skin.

The truth was that the terror I felt went so deep it could have been part of my soul. I had just flown down from the top of the stack that towered five hundred paces high above the surface of the ocean. Five hundred human paces, that is. I hadn’t followed the path, either. I had arrowed down like a gannet towards the sea, driving myself lower with every beat of my wings. All the while, I was thinking: if Kelwyn Gilfeather kills Morthred right now, then I might end up with my feathers splattered all over the ocean. No, not feathers. Skin and flesh. I would be a very dead human, without ever knowing what it was like to be human.

To be quite honest, the closer Morthred’s death came, the less I believed it would not affect the Dustel birds. The less I believed we were immune because we were born ensorcelled…

But apparently Kelwyn hesitated to kill the dunmaster, and I lived a little longer. As I sat there on the rigging I spared a moment to wonder what scared me the most: that Morthred would die—or that he wouldn’t. I couldn’t make up my mind. Both possibilities were entangled with horrors. I looked down from my perch and ruffled my feathers in an attempt to calm my panic. Pull yourself together, Ruarth! Think.

Four people stood on the deck directly below me. None had any idea I was there.

Flame was one of them. She was dressed as she had been while watching the race, in a green gown. The dangling ends of a heavily beaded sash kept the skirt from lifting in the wind. I might have thought it lovely had I not known it’d been given to her by Morthred, a gift from among his plundered riches. Morthred, who had raped her. Who had contaminated her, defiled her, tried to mould her to his image of evil.

She spoke to two sylv women, both subverted now to dunmagickers, and the Amiable’s captain, a one-armed Spatterman I knew only as Kayed. His forearm was missing, something he had in common with Flame, although his was gone from below the elbow, unlike Flame’s which had been amputated above the joint. I suspected he was a foul-mouthed bastard at the best of times; now that he was imprisoned with dunmagic he almost foamed with righteous rage, but powers that were not his kept his mouth from uttering the words he wanted to say.

I switched my attention back to the two sylv women. They were the lucky ones among Morthred’s subverted acolytes; they had not taken part in the stack race because neither of them could swim. All those who had participated were probably dead by now, or at the very least doomed.

‘I don’t care what you think,’ Flame was saying to them. ‘We are leaving now.’ She turned to Kayed. ‘Cast off.’

‘We haven’t paid the port fees—’ the man began. I pitied him; the brown-red of dunmagic played over his shoulders and torso, imprisoning his will with its chains. He could not do much with his rage; every time he tried to resist, the dun-coloured ropes of magic that were looped over his body well nigh strangled him. On our journey from Porth to Xolchas Stacks aboard his stolen vessel, his resistance had almost killed him several times.

‘They won’t see us go, and don’t question my orders or I’ll toss you overboard,’ Flame snapped. Dunmagic rippled outwards from her, foul with coercion. This time the man didn’t hesitate. He turned to his crew and gave the orders to sail. I dithered, trying to think of a miracle that would stop our departure from Xolchasport. I glanced upwards to the top of the stack. Cliffs loured over the harbour, a lethal rockface that could sheer away at any time. Seabirds inhabited every ledge; large and brutal in their language, argumentative by inclination, they were as foreign and incomprehensible to me as fish in the sea.

‘We can’t leave without the Rampartlord,’ the older of the two dunmagickers, a middle-aged woman called Gabania, protested. She’d worked for Syr-sylv Duthrick and the Keeper Council before her subversion to dunmagic.

Flame raised an eyebrow, even though she must have known Gabania was referring to Morthred. ‘Rampartlord?’

‘The dunmaster. Rampartlord of the Dustel Islands. It—it’s the title he prefers.’

Flame snorted. Perhaps she recognised irony. There were no Dustel Isles, thanks to Morthred.

The second dunmagicker, Stracey, waved her hands in agitation. ‘He’ll kill us,’ she whispered.

‘He’s not here, Stracey,’ Flame said and added nastily, ‘but I am. And I will kill you if we don’t leave. Right now.’

Stracey looked at Gabania for leadership and Gabania hesitated, obviously toying with the thought of resistance as she considered her own strengths matched to Flame’s.

‘Don’t do it,’ Flame warned. Then she let the menace in her tone slip away as she added, ‘Listen, this is our chance. Morthred won’t call us back with the force of his will, I promise you. He is going to die any time now and we can go where we will, do what we will. And all the treasure on this ship will be ours…’ I could hear no trace of the Flame Windrider I knew just then. ‘Think of the power we’ll have, Gabania. Dunmagickers, with a ship, and these sailors as slaves, and all the money we’ll ever want. Everything, in fact, that Morthred has amassed over the past few years since his powers returned.’

A flash of hope sparked in the older woman’s voice as the remnants of her independence asserted itself. ‘Morthred’s going to die?’

‘Yes. Those people who tried to rescue me back on Porth—I saw one of them here. I know those people. I know the way they think. They will kill him any minute now, while everyone else is still occupied with the stack race.’

‘Will we—will we be sylv again?’ Stracey asked. She sounded puzzled, as if she didn’t understand her own question.

Flame reached out to cup the girl’s face in her hand. ‘No, sweetie. You won’t. Because you won’t let it happen, will you? You will use you own dunmagic to stay a dunmagicker. Now, go and make sure those fools of sailors obey my orders.’

Obedience to Morthred had made Gabania and Stracey tractable, so they went without further argument. For a moment Flame watched them, then she leant against the railing. I knew what she was doing; I’d seen it often enough. Tendrils of colour floated outwards like a soft mist. Once it would have been silver blue; now it was more a deep lilac colour, and streaked with both silver and reddish-brown. She was going to cover our departure with illusion. It was a form of magic that no longer came so easily to her: it was a sylvtalent rather than a dun skill, and she was losing her sylv.

Above her, I felt ill, with an illness that was lodged more in my mind and heart than in my gut. I had tried to keep my Flame—the gentle, loving Flame—alive, but I really had no idea how to save her. I still didn’t understand her present subversion, any more than Blaze and Kelwyn had last time I’d spoken to them. There was something odd about it. All I could do was hope that once Morthred was dead, it would make a difference. That her own integrity would allow her to fight, to give her a chance.

And above us, in the town of Xolchasbarbican, were the people who might be able to help. Kelwyn Gilfeather, the Sky Plains physician; perhaps there would be something he could do with his medications once Morthred was gone. And the others: Blaze Halfbreed who had proved herself more than a friend; Tor Ryder, the Menod patriarch who would rid the world of magic if he could find a way; Dekan Grinpindillie, the Aware lad from Mekaté—they all wanted to help, but I had no idea how to stop her from sailing away from them and the hope they offered.

I’d assured Flame that there were those who would rescue her, who would ensure she never suffer again the tortures Morthred inflicted on her. She’d listened, I’ll give her that. Then, on the last occasion we spoke at all intimately, she’d held me in the palm of her hand and closed her fingers around my body. Her thumb caressed my throat in a gesture that contained no love, no gentleness, no concern for the fragility of my bones. She raised me to the level of her eyes, only a hand span from her face. ‘I am a dunmagicker,’ she said. ‘I want nothing else.’

‘Flame—’ I began.

‘Lyssal,’ she hissed, reverting to her real name. ‘Call me Lyssal.’ The thumb moved in a circle at my throat. ‘I can crush you, Ruarth, as easily as a thrush crushes a snail shell.’ She tightened her fingers until I found breathing an effort. ‘So simple. So very simple to do.’

I kept absolutely still, feeling the extremity of my danger through the sweat of her fingers. This was not Flame. This was a stranger who wanted to snap my neck.

What held her back? Some remnant of the woman that still dwelled within—the Flame I had known since I was a fledgling living in the crannies of the walls of the palace of Cirkasecastle and she was the lonely, neglected Castlemaid, heir to a throne, who had fed the birds on her window sill?

We were in the Lord’s House in Xolchasbarbican at the time and, perhaps luckily for me, a servant of the Barbicanlord had entered the room just then. Lyssal whispered in my ear, ‘If you ever come near me again I will kill you, Ruarth. Be warned.’ And she opened her fingers, allowing me my freedom.

I had not dared to test her promise. I’d not come near her again, choosing merely to watch from a distance. I continued to speak to her in gesture and whistle, but mostly she did not listen. That was easy enough; if she looked away, she missed all the visual clues and therefore most of what I said. And now, as I looked down from the rigging with my loneliness dragging at me like a yoke around my neck, I could not think of any way to persuade her to stay.

The crew were already hauling in the hawsers. Sailors manned the winches and sails shivered upwards. No one on the wharf as much as looked our way as illusion swirled about us, suffocating, unnatural.

Once, I’d gloried in the sylvpower Flame manifested. Once, I’d seen it as something of value. It had given her a chance to escape the unpleasantness of the fate her father and the Breth Bastionlord contrived for her, backed by the Keepers of The Hub: as a brood mare for a perverted tyrant. The Council of the Keeper Isles had wanted the Bastionlord to sell them his saltpetre and they’d put pressure on the Cirkase Castlelord to give the ruler of Breth what he wanted in return. Lyssal. It was an evil compact, with Flame no more than bait for the sharks. Her sylvtalents had saved her then.

But now, now it was her sylvpower that made her vulnerable to dunmagic subversion. Perhaps, I thought, Tor Ryder is right. The Isles would be better without any magic at all. Perhaps it is an evil thing. Not innately evil—not even Tor thought that—but evil because of the failings of mankind. There are too many people who use sylvmagic in ways that are either petty and trivial, or monstrous. All power, Tor said to me once, should have checks and balances to keep it harnessed. Yet no one can bridle the sylvs of the Keeper Isles.

He should have added: except a dunmaster. Morthred had done a fine job of bridling sylvpower.

A flock of birds flew across the wharf towards me, twittering as they came, each call distinct to my ears. They were saying their names, over and over—it meant nothing; it was just a way we Dustel birds had of keeping in touch as we flew in a flock. Of saying to others in the air about us, ‘I’m right here, by your wing tip.’ They were heading towards me, doubtless to give me news of what was happening in the upper town of Xolchasbarbican. I felt a flooding relief: I would be able to pass them a message for Blaze and Gilfeather.

And then the world lurched.

I have no other way to describe it. Everything around me dropped away, leaving my stomach somewhere above and my mind in limbo.

My last glimpse through avian eyes appalled me: I saw birds turn into people and fall out of the sky. And then Morthred’s death swept over me, changing every particle of my body into something else.

For a moment I truly died.

There was darkness, a blackness so blanketing it contained only emptiness. Silence, an external muteness so intense I could hear the internal sounds of my body being ripped apart, particle by particle. Numbness, a lack of stimulation so pervading I felt I had no body. I thought: so this is what it is like to die.

I plunged into the darkness, into the silence, into the numbness, into that total deprivation. When I emerged, I was on the other side of death, in a life about which I understood nothing.

Everything had changed. Everything. All my senses had been altered so much I couldn’t…well, I couldn’t make sense of them.

I was Ruarth Windrider and I was human.

Well, I’ve read the note you brought from Kelwyn Gilfeather. He says I should talk to you, and so I will, although I can’t say I regard you Kellish foreigners with any particular kindness. You are all far too fond of pontificating on Glorian deficiencies for my liking. I hear tell there are some among you who want to bring in your priests to convert the Glory Isles to your religion; I even hear talk of a fleet of missionaries. What makes you think your beliefs are better than ours? Take my advice, and don’t try it here on Tenkor. We are Menod on these six islands of the Hub Race. Always have been, always will be.

Doubtless you have heard that we of the Tideriders’ Guild don’t always see eye to eye with the Menod Patriarchy, and that is true enough. We are the temporal power on the islands of Tenkor and they are the spiritual power here. In fact, throughout much of the Glory Isles. We often have our differences, but don’t make the mistake of thinking you can divide us; you can’t. When threatened from outside we unite, just as we did back in 1742 at the beginning of the Change.

Guild and Patriarchy affairs have always been entangled so tight it would be hard to separate them anyway. Did you know Menod success in spreading the word of God stems from our Guild treasury? That’s right, Menod wealth came from the longboatmen and tiderunner riders of the Hub Race. Still does. Without us, the Menod Patriarchy would be nothing. Of course, our support is freely given; we of the Guild are mostly Menod, after all.

Me? Oh…I’ve never been much of a one for religious observances myself. I attend the festival services, twice a year, and make my obeisance at the Blessing of the Whale-King, but no more than that. I was born full of sin, riddled through with evil, my father used to tell me, and then he’d beat me for my lack of piety. My reluctance to demonstrate religious devotion should not have puzzled him—for years he refused to allow me to enter the Worship House, saying that until I could control my wickedness I was not allowed the blessings of God. How he thought that would encourage piety instead of having the opposite effect, I have no idea. But then, my father always was a twisted soul.

However, I am still a Menod; do not doubt it. Just not a very good one.

Sorry, I’m rambling. You want me to start with the day the people fell out of the sky? Very well. I’ll begin there. It’s appropriate anyway, because to me that was the day the Change began. Blaze will tell you it started back on Gorthan Spit, but that’s her story, not mine. To me, it began on the day of the Fall. We called it that, hoping an innocuous word would take away the horror; it didn’t. It still doesn’t.

The Fall was a watershed between the old world that went before and the world of the Change thereafter. On Tenkor, we always date events from then. ‘Oh, that happened two years before the Fall’ or ‘Oh, he died about ten years after the Fall’. Most of all, it was just a horror so intense no one who lived through it would ever forget.

I remember everything about it as if it happened yesterday, instead of fifty years ago.

I was down on the waterfront in Tenkorharbour, at the Guild Hall where we tideriders all had rooms. I was idling around, waiting for my turn of duty. I should have been using the time to study—I had a final astronomy examination the next week, followed by a string of papers on rider ethics, wave anomalies, tidal subtleties, and the new sand configurations of the Hub Race. If I didn’t pass them all, I’d have to wait another year before retaking, and that would mean one more year before I had

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved