- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

The unassuming Sky Plains healer Gilfeather is drawn into the adventure of a lifetime, as he joins a warrior and a sorceress on a quest to overcome a ruthless dunmagicker whose lust for dark power places the entirety of the Glory Isles in danger.

Release date: December 21, 2017

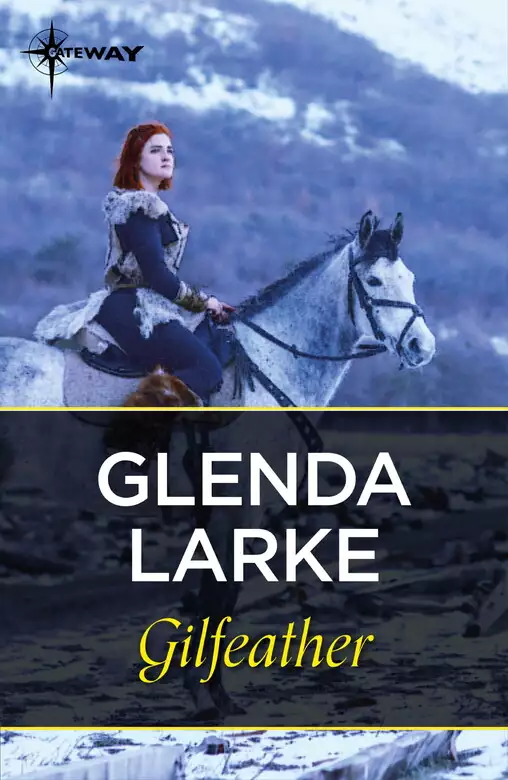

Publisher: Gateway

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Gilfeather

Glenda Larke

Dated this day 28 / 2nd Single / 1793

Dear Uncle,

I do apologise for my lack of correspondence recently; I have been busy preparing information sheets for the Ministry. They are thinking of funding a fleet for a trade journey to the Isles of Glory! You can imagine my delight. I would love to be able to say that our bureaucrats have finally realised official commerce with the Glorian Archipelago would be financially lucrative—and that if we don’t step in, there are other mainland nations who will (the Regal States springs to mind)—but alas, I understand the whole idea is prompted more by pressure from the League of Kellish Missionaries. The religious parties are just cloaking the expedition in the guise of a trade mission in order to obtain government financing, which, as you know, is constitutionally denied to non-secular projects. They have the ear of several cabinet ministers, I believe.

My own feeling, by the way, is that missionaries will find the Glorian Isles a difficult ground to plough for souls. As you may remember from the earlier papers I have sent you, they already have a monotheist religion with a network of priests, called patriarchs, and a lay brotherhood, collectively called the Menod (short for Men of God) that is pervasive throughout the Isles.

Anyway, please find enclosed the next of the conversations for your perusal, translated as always by Nathan iso Vadim. These are from a different narrator, a medic, originally from a rural community of herders who live on an islandom called Mekaté. I do not think he would have talked to us at all, if Blaze had not twisted his arm. I can’t say I liked him much. He was always polite, if somewhat irascible, but somehow I could not rid myself of the feeling that he found me secretly amusing. However, judge for yourself. As usual, there has been little editing of the conversations. We did not try to reproduce any approximation to his accent in the body of the text, for fear readers would find it tedious. It is hard to know how to achieve that anyway, when you are dealing with a translation. These highland herders roll their ‘r’ sounds in a tiresome manner, although some find the musical lilt of their speech attractive. In the translation, Nathan has rendered the man’s direct speech as something akin to our own Kellish highlanders.

Extend my fondest affection to Aunt Rosris, and tell her not to jump to conclusions. She will know what I mean! Anyara and I are both mature adults and are very much aware that an ethnographer such as myself, given to long absences on exploration, would probably make a wretched husband. It is not a situation that either of us have resolved to our satisfaction as yet.

I remain,

Your obedient nephew,

Shor iso Fabold

I first met Blaze and Flame the day before I murdered my wife. The evening before, to be exact. And now it seems I have to tell you about it. Believe me, I wouldn’t be recounting any of this, except Blaze insists I must. She says it’s important that you Kellish people understand the Isles, and maybe she’s right at that, because as far as I can see none of you seems to have displayed any great insight as yet, for all that you have been coming here ten years or more…

All right, all right. Blaze complains I’ve gotten tetchy in my old age. I’ll begin properly.

It was in the taproom of an inn in Mekatéhaven, on one of those hot, humid nights when the air seems so thick that it’s hard to breathe. I remember the sweat crawling down my back to make a wet patch on my shirt. I actually had a room upstairs, but it was an airless cubbyhole I wanted to avoid. It overlooked the wharves, where ships fidgeted endlessly at their moorings and sailors and longshoremen squabbled all night long, so I’d decided to spend the evening in the common room. I had no intention of being sociable; I was mired so deep in my own troubles that all I wanted to do was nurse a tankard of watered-down mead and wonder what in all Creation I could do to solve problems that were all but insoluble.

My immediate difficulty was that I needed to go to the Fellih Bureau of Religious and Legal Affairs, and it had closed for the day. Until they opened in the morning, I wasn’t going to be able to find out what had happened to my wife.

In the meantime, worry lurked in the pit of my stomach like over-spiced food promising unpleasantness. All I had at that point was a piece of paper telling me that, as the husband of Jastriákyn Longpeat of Wyn, I was expected to present myself as soon as possible at the Bureau. It was an imperious summons and there was no overt reason why I should answer it. Neither Jastriá nor I was a Fellih-worshipper and neither of us ever had been. Moreover, Fellih-worship was not an official religion, and the leader of the faith, the Exemplar, had no official status on Mekaté Island. The Havenlord himself was Menod and, as far as I knew, so were most of his Court and his Guard.

Nonetheless, the summons had given me a bad feeling and I hadn’t hesitated: I set off for Mekatéhaven immediately. I even brought my selver all the way downscarp—which would be much frowned upon by the elders of my tharn if they ever found out—so that I could travel more quickly. The journey had still taken me a couple of days and when I arrived, it was to find the Bureau closed for the day.

So there I was, sipping my mead and paying no attention whatsoever to the other occupants of the inn. Trying, as much as I could, to ignore the fact that I was surrounded by dead wood. Trying even harder to ignore the smell of the place: the sharpness of coal smoke, warm toddy and spilt wine permeated everything inside; the muted scent of mould, mangrove mud and damp sails wafted in from outside. I was vaguely aware of a group of people playing cards on the other side of the room, of several merchants discussing business near the door, of a woman sitting alone at the table in the far corner. Apart from that, I was oblivious. All I could think of—with a mixture of exasperation, love and frustration—was Jastriá. What in the wide blue skies had she done this time?

‘More mead, syr?’ The barkeep hovered at my elbow with a jug.

The title he gave me was not one I was entitled to, and I was sure he knew that. I shook my head, wishing he’d just go away.

But business was quiet, and he was talkative. ‘Just come down off the Sky Plains, have you?’ he asked, stating the obvious. I had a selver in his stable and I was wearing a tagaird and dirk, after all.

I nodded.

‘You must be tired. Can I ask my wife to get you a meal, maybe?’

‘I’m not hungry.’ I made a gesture of negation that would have set my tankard flying if he hadn’t grabbed it in time.

He set it carefully back on the table. ‘Ah, you’re finding the heat and humidity oppressive, I suppose. You Sky People do, so they tell me,’ he added, cheerfully mopping up the spilt mead that had slopped on to the table.

‘Ye get other Plainsmen in here?’ I was surprised. Not too many selver-herders ventured down off the Plains, and with good reason. Who wanted to suffer the appalling weather of the coast voluntarily, not to mention the filth of its streets and the narrow-mindedness of its townsfolk? We were all Mekatéen, but the selver-herders of the Sky Plains and the town dwellers and fisher folk of the tropical coast had little in common.

‘Sky People here? Oh sometimes, selling selver wool or paying taxes,’ he said, deliberately vague, and I realised he had not expected me to take him literally. I smothered a momentary irritation. We relied so much on smell on the Roof of Mekaté, it was sometimes hard to use and to understand the conversational gambits and niceties of the coast. I still made mistakes; coastal folk often found me abrupt, even rude, and their courtesies were often just lies to me.

He must have taken my question as an indication that I wanted to talk because he leant in closer and said in a conspiratorial whisper, ‘Have you noted the Cirkasian beauty in the corner?’

I hadn’t, not really, but after I glanced at her I doubted that he’d believe that. The woman sitting alone in the corner was astonishingly beautiful: gold-blonde hair, with eyes the colour of the sapphires we used to pick up sometimes in the streams of the Sky Plains. Her one flaw was that she had only one arm: the other ended just above the elbow. She was wearing travelling garb stained with salt water. She smelled of salt and fatigue and some faint animal scent I didn’t know, all laced through with a strong aroma of perfume. One of those over-spiced tropical scents: chypre? Patchouli? Spikenard? I wasn’t sure.

‘Now what’s a sea-dream like that doing in a bar alone at night?’ the barkeep asked. ‘That’s what I’d like to know.’

I shrugged and he sighed. ‘Business just gets worse and worse,’ he continued, leaning into the table, his rotund belly coming to rest on the planks. ‘It’s the Fellih-priests to blame. They don’t like drinking. They don’t like card-playing. They don’t like music. They don’t like dancing. Or whoring. Or gambling. Or just about anything that’s fun. Which I wouldn’t mind, if they kept their ideas to themselves, but no, they have to make non-worshippers feel guilty about doing those things, and believers who indulge just get thrown in jail. It’s got so that when a bunch of them walk in for a meal, the drinkers leave.’

I was startled. Things hadn’t been that bad last time I was on the coast.

I didn’t travel all that much any more, not since Jastriá and I had parted, but I was a physician and there were certain herbs and medicinal ingredients that could only be procured away from the Sky Plains. The lowland forests of Mekaté may have been no more than a narrow trim to the highlands, a ruffle between the bottom of the scarp and the sea, but they held a diversity of plant life that was both breathtaking and invaluable to a herbalist. And so I made the journey down to the coast at least once a year, either buying from medicine shops or collecting my own plants in the forest. I tried to keep the trips short: what I saw along the Mekaté coast invariably broke my heart.

The barkeep rambled on. ‘You Plains people have more sense. You don’t worship the Fellih-Master, do you?’

I shook my head, snorting at the thought of selver-herders bothering with the doctrine of Fellih. We were far too pragmatic; far too content. Oh, Fellih missionaries had attempted to penetrate the Plains with their ideas, as had the Menod, but they’d all met with a rock-solid wall of indifference and had eventually taken their concept of God, sin and the afterlife elsewhere.

I was still wondering how to get rid of the barkeep, when one of the card players called for a round of drinks and he levered himself upright to attend to them. I decided to finish my mead and go up to my room, but while I was sipping the last of the drink, I smelled something that seemed out of place. Feathers. I could definitely smell feathers, and an inn room late at night seemed an odd place for a bird.

Idly curious, I glanced around. It was a while before my eyes saw what my nose had identified: a nondescript blackish sparrow-like creature sitting on the rafters near the table where the card game was going on. I didn’t know the species, but it surely didn’t belong in a taproom. It seemed restless; I could see it cocking its head to look down from its perch, and occasionally it would shuffle its feet and flick its wings. Once it even flew across to one of the other beams, and then back again. Obviously the poor thing had become trapped inside the room and didn’t know how to get out. I empathised.

The players at the table were noisy. Three or four of them were well on the way to being drunk, two of the others were arguing amiably about the previous hand, and whether it had been luck or skill that had resulted in the sole woman among them winning a handsome amount of money. I had never played cards and didn’t understand the conversation, but it seemed to me that there was an odd sort of tension in the group. Someone wasn’t happy with having lost, and the woman was uneasy, although she hid it well. Suspicion tendrilled in amongst the sounds, pungent in a way that was quite different to the sharp tang of the ale in the casks along the wall or the bitters stewing in the brewery room out back.

I began to pay attention. I sat up and edged myself along the bench, thinking to leave for my room quietly and unobtrusively. Instead I managed to topple what was left of my drink on to the floor. No one among the card players even bothered to look at what had caused the noise. It was definitely time for me to leave.

As I bent to retrieve the tankard, one of the card players, a young fellow with a strident voice and a drink-flushed face, flicked some money into the centre of the table and said, ‘Your bet, sister. Match that, if you can.’

The woman looked up at the rafters, apparently considering the bet, then laid her cards face down with a shake of her head and a smile. ‘No,’ she said. ‘I think not. This pot is yours, my friend. In fact, it is time that I went to my bed.’

‘Wait a moment.’ Another of the players placed a hand over hers as she reached out to gather her own money together. ‘You can’t win all that money and then just walk out of here!’

She stared at him, all hint of the smile gone. If I had been one of her companions, I would have been worried; there was something about her that made my nose tingle. ‘Oh, but I think I can,’ she said, removing her hand. ‘If you don’t want to lose, then you shouldn’t play. Th—’

She never finished what she had been about to say. Even as I rose to leave, the main doors to the inn were pushed open and a crowd of people surged in.

Not customers, that was immediately apparent. One of them wore blue robes, stacked shoes and a cylindrical hat with a small brim; Fellih-priest garb, I knew that much. The rest looked like thugs; they carried long wooden cudgels with rounded ends. The priest scanned the room with a glance then gestured towards the card players. The cudgels moved to surround the table. The silence in the taproom was instantaneous. The merchants just melted away, leaving by a side door. The Cirkasian woman didn’t move and neither did I.

The card-playing woman did move, but her movement was so controlled and unobtrusive, I doubted the newcomers noticed. She placed one hand on the hilt of the sword in the scabbard that had been hanging on the back of her chair. I was intrigued; I had no idea that there were women who used swords. I hesitated, torn between drawing attention to myself by leaving, or simply staying put.

The barkeep spoke up. ‘Syr-priest, I beg you, this is a respectable house—’

The priest withered him with a look. ‘Respectable establishments do not allow gambling.’

One of the young men at the table rose to his feet, belligerence in every nuance of his stance. ‘Syr-fellih,’ he said, ‘what possible business do you have here?’

‘The Master’s business,’ the priest replied, and his tone had all my senses tingling. ‘You have broken your faith with the Fellih-Master, lad.’ The ‘lad’ in question must have been all of twenty-five, so that was an insult there to start with. ‘Show me your thumbs.’

The man reddened from the neck upwards and I could smell both his fear and his resentment. Reluctantly, he held out his hands. The Fellih-priest glanced at them and nodded to the cudgel-wielders. ‘And the rest of you,’ he said to the card players.

One of them answered calmly. ‘That will not be necessary. We freely admit it: we are all Fellih-worshippers here, except for the lady. And we have indeed fallen from Fellih’s grace tonight. For that I apologise. We will abandon this place of iniquity and go home chastened, to pray for Fellih’s forgiveness.’ He rose and bowed deeply in the direction of the priest. Only then did I notice that he too wore the high-stacked shoes of the Fellih-worshipper. In fact, they all did, except the woman.

If he thought that would be an end to it, he was mistaken. ‘I think not,’ the priest said. ‘The penalty is more than penance, lad. It is imprisonment and a fine.’

The resentful one said hotly, ‘You overstep your mark, Syr-priest! I am the son of the Burgher Dunkan Kantor, and my friends are—’

‘No man and no man’s son is above the Master’s law.’ The priest nodded once more to the cudgel-wielders. Within seconds the young men were hustled outside, their protests ignored. The priest turned his attention to the woman. ‘And you,’ he said. ‘Let me see your thumbs.’

I thought for a moment that she was going to refuse, but there were still four cudgel-men behind the priest and finally she shrugged and held out her hands, one at a time. The priest nodded, satisfied. He looked back at her face; then, without warning, he reached out and brushed the hair away from her left ear. It was bare: she lacked a citizenship tattoo. The subtleties of the physical differences between people from different islandoms was beyond me, but something in her looks—she was tall and tan-skinned with brown hair and startlingly green eyes—told him she was the result of inter-island mixing.

‘Halfbreed,’ he hissed, and the hate in that one word left me gaping. How could one despise another simply because of an accident of birth?

‘That’s right,’ she said calmly. ‘And I arrived in Mekaté only this evening.’ She was lying, I could tell, but I doubted anyone else could. She was as unruffled as a mountain tarn. ‘The law says the citizenless may have three days residence before they must leave.’

‘You have corrupted our young! Card-playing!’ His bile was a tangible thing that made me flinch.

She gave him a flat stare. ‘I don’t remember having to teach them how to play. Or how to wager their money. They seemed to be well acquainted with the procedure before I arrived.’

‘Your behaviour is typical of the improperly bred and we don’t want your kind here. Show me your branding.’

I winced at his tone, at the smell of his barely-leashed fury. She seemed unworried by the way his eyes narrowed and his voice flattened, but his words stilled her nonetheless. My breath caught in my throat. She had a magnificence about her, a dignity that transcended her situation, that made him look like what he was: a small and petty man. But there was more than dignity; there was a deep and abiding anger that made her seem dangerous even without a sword in her hand. The tension in the room ratcheted up a notch. Without a word, and with a controlled economy of movement, she untied the top of her tunic and bared her back so that he could see the mark there. It was an ugly thing, a scar burnt deep into the skin of her shoulder blade in the shape of an empty triangle. It had not healed well and the skin around it was puckered.

She readjusted her tunic. ‘Forgive me,’ she said, and her irony was mere surface covering to a deep churning rage, ‘I did not know gaming was against the law here. It was hardly obvious. With your leave, I shall be on my way.’ She turned away from him, perhaps to pick up her sword harness.

What happened next was so swift that the warnings shouted by myself and the Cirkasian were too late. The priest made a sign to one of the four remaining cudgel-men, and as quick as a spitting selver, the man brought the club down on her head. She had warning enough to turn so that much of the force of the blow was taken on her shoulder. Even so, she came up groggy and at a disadvantage. Or I thought she did, but a moment later I wasn’t so certain. As she reeled, one of the other men tried to throw her, hard, into the wall. She ducked down as if staggering, and somehow the fellow pitched right over her back. Before he hit the floor, she straightened and it was his head that collided with the stones of the wall, not hers. He was out cold. It all looked accidental, but something about the fluid grace of her movement had me wondering. Still, she was pale enough, and had to prop herself against the wall in order to stand. A trickle of blood matted the hair over her temple. I doubted that her dizziness was feigned; she was close to blacking out and action had made her feel worse.

I stepped forward in protest. ‘Wait a wee moment,’ I said to the priest, ‘that wasna necessary! Ye have hurt the woman and she was offering no resistance. I am a physician; allow me to examine her. Him too,’ I added as an afterthought.

The priest looked at me coldly. ‘We need no heathen medicinemen interfering here.’

‘They may be concussed—’

‘Do you dare to countermand me, herder?’ he asked, his distaste clear. He signalled to the remaining cudgel wielders. One of them grabbed her arms and forced them behind her back; another had her in manacles before she had time to protest. They’d obviously done this kind of thing before, often. The priest gestured and they hustled her away through the outside door. Beside me the Cirkasian was also on her feet, her face as pale as a meadow snowbell. The priest turned back to us. ‘Your thumbs,’ he said to us both.

I blinked and blundered on. ‘She needs attention—’ I went to shoulder past him, but he blocked my way with his hand upraised. ‘Then let me tend the man,’ I said indicating the fallen thug who was only now beginning to stir.

‘Your thumbs,’ he snapped. There was so much authority in his tone that I halted.

The Cirkasian shrugged and held out her hands. He looked, nodded in satisfaction, and turned his attention back to me. I had no idea what he was looking for, but let him look anyway. He seemed satisfied and said, ‘You are both strangers here. Follow the example of the pure of heart and you will be welcome on the coast. Be not seduced by the sins you have witnessed in this mire of immorality tonight.’ The smell of his sincerity cloaked him, wisping through the air in swirls. He believed what he was saying. Behind him the dazed thug staggered to his feet and looked around to locate his friends.

‘Oh, I dinna think there is any chance of that,’ I replied without inflection. ‘They are not sins I would want to emulate.’

He hadn’t the imagination to hear sarcasm. He inclined his head and strode to the table where the money from the card game was still piled up in heaps. He took out his purse and scooped up the money in the centre. There wasn’t all that much there; most of the cash was in the separate piles belonging to the players, but he ignored all that and strode out of the inn. He also left the halfbreed’s sword, which was still hanging on the back of the chair.

I took a step towards the injured man, intending to offer my help, but he bolted out of the door. The Cirkasian sat down at the gaming table in silence. I turned back to the barkeep. ‘What was all that about thumbs?’

‘Oh—Fellih-worshippers: they have their thumbs tattooed with blue circles, at birth or conversion.’

‘And if a man changed his mind about his beliefs?’ I asked.

He looked at me as if I was too innocent to be real. ‘Once a Fellih-worshipper, always a Fellih-worshipper. It’s not a faith you can ever leave. Not alive, anyway.’

‘That—that’s unbelievable. Parents can sentence their children to a lifetime of commitment?’

He shrugged to indicate that he shared my lack of understanding of that rationale.

‘And the woman’s brand on the shoulder?’

‘That’s to show she has been made barren. They castrate halfbreed men and sterilise the women, then brand ’em to show it has been done.’

‘They? Who does?’ I had heard of the practice, come to think of it, but for some reason or another I’d thought it’d fallen into disuse.

He shrugged as if the question made him uneasy. ‘Authorities. Here it’s the Fellih-priests or the Havenlord’s Guards. It’s the law in all the islandoms, though I’ve heard the Menod patriarchs preach against it.’

‘That’s barbaric!’

‘Plainsman,’ he said kindly, ‘you best go back where you belong. The world’s too bad for the likes of you.’

I grimaced. He was probably right at that. I glanced over at the gaming table, about to remark on the money left there, only to find it had vanished. The Cirkasian was walking towards us, the other woman’s sword in her good hand.

‘Ye can’t do that!’ I blurted without thinking.

She looked at me, innocently bewildered. ‘Do what?’

‘Take all their money.’

‘What money?’

‘The money they left on the table.’

‘The priest took it.’

‘He only took part of it!’

I looked at the barkeep, wanting him to support me, but all he did was stare back in a puzzled fashion. ‘The priest took it,’ he said. ‘He took it all. I saw.’

The Cirkasian nodded. ‘Where will they take the card-players?’ she asked.

‘To the Fellih Bureau of Religious and Legal Affairs,’ the barkeep said. ‘There are cells there. Tomorrow they will come up against the Fellih magistrate. There will be lawyers for both sides who will quote the Holy Book, which is of course the inspired word of Fellih, and the one with the best quotes wins his case.’

I gaped. ‘That’s absurd.’ I was not all that familiar with the concepts of courts, lawyers and magistrates—we did not have such things on the Sky Plains—but even so, what he said seemed ridiculous.

‘Not to a Fellih-worshipper,’ the barkeep replied. ‘They believe Fellih is omnipotent and cannot make mistakes. So if the magistrate and the lawyers pray for guidance, which they do, the result must be the wish of Fellih. Simple logic.’ He snorted. ‘Which is one of the many reasons I’m a Menod, rather than a Fellih-worshipper.’

I warmed to the man, but I didn’t want to get into a religious discussion. Up on the Sky Plains, we didn’t believe in any gods at all, which seemed much more sensible. I looked back at the Cirkasian. ‘And ye maintain ye didna take the money? And what about the sword ye’re carrying?’

She looked startled. There was a pause, and then she said, ‘I am not stealing the sword.’

I blinked, confounded. The weapon was in her hand, after all, but she spoke with an honesty that was bewildering in light of the evidence.

She nodded to us both and headed for the stairs.

I looked back at the barkeep, but his garrulity seemed to have vanished. In fact, he was edging away as if he was having second thoughts about my inoffensiveness. I said goodnight and headed for my room as well—perplexed, but aware that it would be stupid to make a fuss. None of it was my business.

I was halfway up the stairs when I felt I was being watched. I turned to look, and the single eye that met mine belonged to the bird. The same bird as had been on the rafters, but it had moved to the newel post. It stood there regarding me until I turned away and resumed the climb to my room. I had a strange feeling that I was way out of my depth; a bird should never have had the emotions I could smell in that one.

I was at the Fellih Bureau of Religious and Legal Affairs early the next morning, my anxiety pungently tangible, at least to me. To my surprise, there was already a crowd of people gathered in front of the building. Most of them were well-dressed merchants in the company of their wives and servants. Some of the women were weeping; the men were as sombre as their clothes. They stood about talking while they waited for the office to open, their hands fiddling with their prayer beads, their feet shuffling in their uncomfortable shoes.

‘What’s going on?’ I asked a man across the road who was selling snacks of grilled sea-snails, fresh from the coals. The smell was pervasive and made the end of my nose twitch.

He shrugged indifferently as he stirred the snails on the wire grill, rolling them about with his spatula. ‘They arrested some of the sons of the merchants last night for gaming. The parents have come to get them released.’

I watched the people milling around. One woman near me hugged another, moaning, ‘Leeitha! Haven’t I always told him to be a good boy? I forbade him to go out at night and he wouldn’t listen!’

She was dressed in red, with a blue shawl flung over her shoulders and leather sandals on her feet. As she was a woman, no one cared if her feet were contaminated by the dust. Men—whether priests or laymen—had to wear the high-stacked shoes, and were not permitted to touch the soil or earth, or wear any colour except blue. They weren’t supposed to walk about the streets alone either; in fact, their Fellih-faith obliged them always to be in twos or groups, supposedly to ensure the good behaviour of each individual. Restrictions placed on a Fellih-faithful woman were not as stringent, as long as she did not commit adultery or tempt the menfolk with her behaviour or dress. Jastriá had once explained that anomaly to me. It stemmed not from a more liberal attitude to women, but from a rather nasty aspect of the religion: women were not considered worth troubling oneself about. The Fellih-Master was contemptuous of women and the Holy Book was full of tales of their empty-headed, superficial femininity that was capable of neither piety nor scholarship. A woman, it seemed, went to paradise only if her husband accumulated s

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...