- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

ONLY A TRAITOR CAN SAVE THEM

When sailors came to Ardhi's homeland, they plundered not only its riches, but its magic too. Now disgraced islander Ardhi must retrieve what was stolen, but there are ruthless men after this power, men who will do anything to possess it...

Sorcerers, pirates, and thieves collide in this thrilling sequel to Glenda Larke's epic fantasy adventure, The Lascar's Dagger.

Release date: January 13, 2015

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 464

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

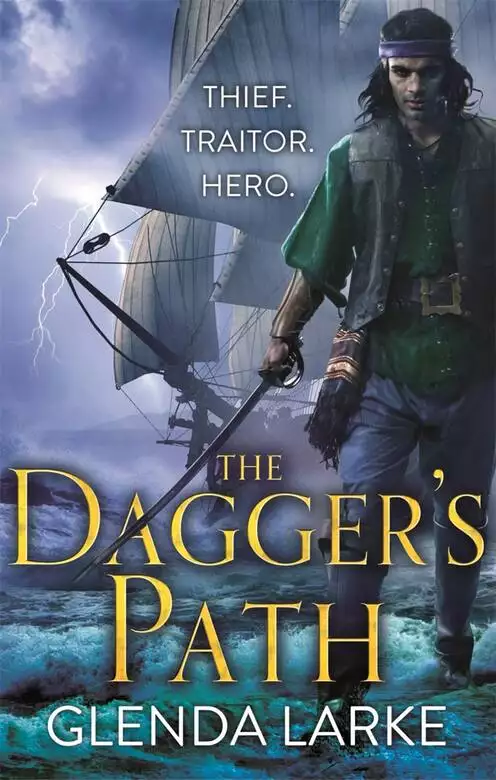

The Dagger's Path

Glenda Larke

Lookout duty aloft lent itself to the pleasant diversion of daydreams. Memories too, but memories were a trap, because you didn’t always know where they might lead you…

The mast creaked under the strain of wind-filled sails, the tang of salt and wet canvas saturated the air, but in the crow’s nest, memory had snared Ardhi in his past. He smelled the smoke of mangrove charcoal burning in the kilns and heard the hammering in the forges of the metalworkers’ village. His thoughts lingered in that other world, recalling the greying attap roofs of the houses on stilts and the rows of fish drying on the racks in the sun.

His grip on the railing in front of him tightened as he remembered the day he’d gone there to see the blademaster, the empu Damardi. He’d been sick with guilt and shame. His pounding heart had matched the sound of the hammers; the whiff of molten metal had tasted bitter to his tongue.

With clammy fingers, he’d straightened his loose jacket, brushed a streak of dirt from the hem of his pantaloons and checked for any untidy strands of hair escaping from under his cloth headband. He’d made sure that his kris, his father’s coming-of-age gift, was neatly tucked into the waist of the sampin wrapped around his hips. Finding nothing that would hint at disrespect for the man he was about to visit, he’d walked on past the lesser smiths until he came to the house of Damardi, the greatest krismaker of all.

Once there, he did not mount the steps to the serambi, the raised porch, as a normal visitor might. Instead, he’d knelt on the bare swept earth in front of the house. He’d taken the plume he carried from its sheath of protective bambu and laid it on the ground. In the mango tree overhead, the bird they called the macaque’s slave scolded its noisy warning at his intrusion.

The villagers went about their business, muttering to each other while they ignored him with calculated insult as he knelt there in the heat. Remorse suffused his face and neck with red. They all knew his careless words had brought the unimaginable to the Pulauan Chenderawasi. He’d told the pale sailors of paradise birds, and they’d come a-hunting.

They’d shot Raja Wiramulia with their guns, killed him for the golden plumes of his regalia even though they knew nothing of their true sakti, the Chenderawasi magic with which they were imbued.

Kneeling there in the metalmaker’s village, mortified, Ardhi wanted to die.

The village boys were less mannerly than their elders. They spat on him and whispered as they passed by, “Betrayer. Traitor. Moray, moray, moray!”

He shuddered and hung his head at the insult. The despised moray eel was the hated assassin of the reef, darting out of its dark crevasse to seize unwary prey.

An hour passed before Damardi stepped on to the serambi and placed his hands on the railing. “Who comes to speak to the bladesmith?” he asked, looking down on him. “You, young Ardhi? How dare you bring the Raja’s plume here, still stained with his blood!”

“The Rani bade me ask for a kris to be made, empu. Who else is skilled enough to craft such a blade?” He picked up the plume and held it in both hands, offering it to the old man. Damardi would need some of its barbules to fold into the metal.

Yet the blademaster swelled with rage. “Such a kris is borne only by a warrior-hero in the service of the Chenderawasi. Are you such a hero? Are you even a warrior?” His scorn was scarifying and his grief seared.

Yet Ardhi couldn’t look away. “Empu, it is the Rani’s wish.”

Tears slid down the creases of Damardi’s wrinkled cheeks to pool at the corners of his mouth. He made a gesture with his hand without turning around and, in answer, his granddaughter emerged from the door behind him. Lastri.

Lastri, with her long black hair and lithe body, her shoulders bare above the tight wrap of her breast cloth. Lastri, whom he had loved so well. Lastri, who’d swum naked with him in the lagoon by night, and lain in his arms on the sand after they’d made love by moonlight. Lastri, who had pledged herself to him, just as he had sworn his love for her.

Now she carried half a coconut shell cupped in both hands and the curve of her hips shivered him with its reminder of all he’d lost.

“The Rani sent me the blood of the Raja,” Damardi said, his voice cracking as he gestured at the contents of the shell. “This will be used to damask the blade.” His unflinching gaze fixed on Ardhi’s like the eye of a sea-eagle on its prey. “I must obey Rani Marsyanda. I will make this kris, although every song in my soul screams at me that you are unworthy of it. Leave the plume. Return after two moons, and the kris will be ready.”

“Two months is too long, empu. The kris is needed now.”

“Revenge can always wait.”

He licked dry lips. “It is not needed for revenge. That, I could achieve with my bare hands.”

“Then why?”

“The pale men still have the other plumes. They took them on board their ship and sailed away. I need the kris to follow the regalia, that I might find and return the plumes to their rightful place.”

Lastri gasped, her eyes widening. Damardi’s knuckles whitened as his grip on the porch railing tightened. “These pale men, these ugly banana skins, do they know the power lurking within the plumes?” he asked.

“No.”

“At least you had a rice grain of wisdom left in your empty, traitorous skull.”

He hung his head in silence.

“But a kris containing the sakti, the magic of the Chenderawasi? Such a kris cannot be made in an hour, or a day, or a single moon. The metal must be folded and refolded, the blade must be waxed and soaked and damasked to its edge. Every step must be perfect, otherwise how can it be endowed with its sakti? Two months, Ardhi.”

“And there’s the hilt,” Lastri murmured. “Who is to craft and carve the hilt?”

“The Rani. She will use…” But Ardhi couldn’t finish the sentence.

“I know what she will use,” the old man replied, scowling. His eyes glistened. “And she will have already cut what is needed from the body of her husband.”

With those words, Damardi appeared to shrink before Ardhi’s eyes. The wrinkles on his cheeks burrowed deeper and his eyes shadowed darker under the heavy overhang of his brows. “Very well,” he whispered. “I will craft a Chenderawasi kris, but to do it in seven days, a price will have to be paid.”

“I will pay it.”

“You do not know what it is.”

“Empu, if a price has to be paid, then it is mine to pay, and it shall be done.”

“Indeed.” Damardi nodded. “You will stay with me for those seven days. Your strength will aid me. But when it comes to the power of a Chenderawasi kris, your promise to sacrifice your life will be the spark that awakens the Raja’s blood and the plume-gold of his regalia. There is no other way. For without a sacrifice, the sakti of this kris will rouse too slowly to give it life.”

Grief-stricken, Ardhi bowed his head. “I need to live, empu. I need to live to seek, find and return the plumes.”

Damardi frowned, considering. “Then the day you return with the plumes will be the day of your sacrifice. That promise and those undertakings I will fold into the blade. Your blood to be spilt, and your life freely given to the blade of this very kris. If you do not return the feathers, then the kris itself will turn on you in punishment and take your life no matter where you are. You have no future beyond your quest, Ardhi.”

He nodded, his grief cold with fear and rock-hard in his breast. The time of his death had been decreed. So be it. Yet he wept at the thought.

He was only eighteen.

Glancing at Lastri, he winced. Her face was a mask, her eyes dulled with grief, but her stance said something else. She was enraged, furious at him for what he had destroyed: their future together.

“Now go,” Damardi said. “Build a fire in my forge, so we may heat the metal. I have the best Pashali iron, and we will mix it with the dark-silver sky iron from the heavens, collected long past in the mountains. We shall add the root of the graveyard tree and the leaves of the tree of life. This kris will have a bird’s-eye damask at the point and the stem, to ensure that its future is auspicious. Its power will carry the sakti of the islands across the seas to aid your task.” A tear trickled down his cheek. “You are not worthy of such a blade.”

Pulauan Chenderawasi. The nutmeg islands.

Agony to have the memories play again and again before his eyes–yet how to stop them?

Perhaps it is punishment, Ardhi thought. Perhaps it was all just to remind him that even if lives were ruined, he had to believe in the rightness of what the kris was doing. The path of the sakti of the Chenderawasi was always true.

He looked up at the sails of the Spice Winds and dragged his thoughts back to the present. He had to understand why the dagger had brought the four of them–Saker, Sorrel, Piper and himself–together on board this ship on its way to the Spicerie.

Splinter it, though, now is not the time to think about it. He was on lookout duty. He turned his attention to the ocean.

On the horizon ahead, the Regal’s aging galleon, Sentinel, wallowed along with its impressive array of cannons. Keeping pace to either side of Spice Winds were the two other new fluyts designed for spice cargoes; and far behind, with a topmast splintered, limped the elderly carrack Spice Dragon. It was a miracle that on this, the first day of watery sunshine they’d had since leaving Ustgrind, the Lowmian fleet was still together. It had taken a whole moon month to emerge from the storm-scoured waters of the Ardmeer Estuary, followed by fourteen more miserable days of appalling weather as the fleet rounded the Yarrow Islands and lost sight of land.

His mind began to wander again, to a sun-sparkled sea where the waters were brighter, the skies a deeper blue. Even the seabirds there spoke other tongues…

The kris at his hip slithered in its sheath, pushing against his thigh. He jerked in surprise. The blade hadn’t as much as glinted for weeks, let alone moved of its own volition. He drew it out, and the point swung downwards. He looked through the slats of the floor of the crow’s nest to see what had prompted its awakening.

Sorrel, who rarely left the hastily converted storage cuddy that was her cabin, was on the weather deck with Piper, glamoured so none of the sailors could see either of them.

Ardhi felt a stab of sympathy at her loneliness. Captain Lustgrader had decreed she stay away from the crew at all times–except for Banstel. Barely thirteen years old, the ship’s boy milked the goats, washed Piper’s swaddling and brought Sorrel’s meals to her.

He might have known that she would sneak up on deck now that the weather was better. She had courage and determination, that woman. He admired the set of her shoulders, the lift of her chin at any hint of adversity, the steel in her gaze when she was threatened. What he didn’t understand was why the dagger’s sakti had manipulated the weather to ensure she couldn’t leave the ship, as she’d wanted. As for Piper, the baby–he couldn’t fathom who she was at all, or why she was here.

He fingered the hilt of the dagger, taking courage from the feel of the Raja’s bone beneath his fingers before slipping it back into its sheath. He should have felt satisfied. Those bulging sails around him were filled with cold northerly winds driving the ship towards the Summer Seas.

He was heading home. The three pillaged plumes of the Raja’s regalia were safe in his baggage, and the fourth feather, the one he had been granted by the Rani to aid his task, was close by in Commander Lustgrader’s hands. He could retrieve it once Saker no longer needed to use its power to coerce Lustgrader.

Sri Kris had prevailed in the Va-cherished Hemisphere, had done everything that had been required of it.

Except kill him.

Skies above, why did he find that so hard to accept? He’d agreed to it! Yet his spirit rebelled and his thoughts darkened with defiant anger. He wasn’t eighteen any longer, but he wanted to lash out at his fate, wanted to do anything just to go on living.

Down on the deck, Sorrel looked up at him. Her gaze locked on his, and her mouth curved up in a smile. Without thinking, he smiled back and felt a sudden surge of desire. For her perhaps–or maybe just a longing to find desire and passion in a woman’s arms again, someone, somewhere, before he died.

The ship’s bell rang. His watch in the crow’s nest over, he scanned the horizon one last time. Spice Dragon was falling out of sight behind. Not a good idea to scatter too widely, not when Ardronese privateers might be waiting to pick them off, although that was unlikely while their holds were still empty of spices.

As he headed down the shrouds, a wind-rover approached the ship, skimming the waves. He halted his descent to watch, fascinated by its effortless grace as it banked. Its wingspan was greater than his own outstretched arms. It rose to cross the ship just over the mizzen mast, then swung around behind the stern, only to return at a lower level coasting towards the aft deck. Saker was standing at the stern rail, and Ardhi didn’t need to be told he was calling the bird in. It wasn’t the first time either; the man had done this at least once before on this journey, perhaps more.

Witan Saker Rampion, masquerading as Lowmian Factor Reed Heron. There’s more to you and your witchery than you guess.

The wind-rover matched its speed to the ship, cruising, spreading the feathers of its tail and dropping its legs, flying lower and lower until it touched down on the decking. It folded its wings over its back and ruffled them uneasily, then lowered its head to hiss its aggression.

The helmsman, with his back to the raised poop at the stern, didn’t see what was happening, but other sailors working further along the deck noticed and gaped. Saker knelt beside the gigantic bird, stroked its head and neck until it relaxed, then bent to do something to one of its legs. From above, Ardhi couldn’t see exactly what, but a few moments later the bird rose from the deck, its spread wings easily catching the lift of the wind. It banked away from the ship and vanished between the swell of the waves.

Ardhi climbed on down to tell the officer of the watch about the lagging Spice Dragon.

Gunrad Lustgrader, commander of the fleet of the Lowmian Spicerie Trading Company and captain of Spice Winds, sat at the desk in his cabin. Lying in front of him, next to an empty length of bambu, was the paradise-bird feather Reed Heron had gifted him. Billows of gold and orange and red enticed him to stroke the plume, to revel in the sensuous thrill of its touch. The glow of its ambient light was warm and welcoming. Magical.

For a moment he was transported back to the islands of the Summer Seas and inhaled again the perfume of the flowering cinnamon and the musky scent left around the villages at night by roving civets. The warm coral sands scrunched underfoot once more and the glory of birdsong filled his ears, sounds so ethereal that tears pricked his eyelids.

He wrenched himself into the present.

Scupper that. The plume was uncanny and it held him in thrall. He knew that and fought it, so why was it a battle where victory always seemed just out of reach?

On his last voyage, he’d seen men in Kotabanta happily disintegrate into drooling fools after inhaling the smoke of burned tree sap. Such madness! The rational part of his mind told him he was like that, drugged, no longer in command of his own destiny, captured–not by smoke–but by cursed sorcery from the Va-forsaken Hemisphere.

That bastard scut, Heron. He’s to blame.

Appalling snatches of the day they’d met, not fully recalled and never quite in focus, floated through his memory. He couldn’t dismiss them as inaccurate; they stayed, nagging, an ache eroding his sanity.

Tolbun, first mate, had even bluntly told him that the whole ship’s company wondered at the way he fawned before Heron, and puzzled over why he’d ever allowed that flirt-skirt and her squalling baby on board.

He knew his behaviour was deranged, yet couldn’t change it.

One day soon, Factor Heron, I’ll see you keel-raked, your skin shredded on the barnacles, your back flayed to the bone, and if you survive that, I’ll hang you from the yardarm. As for that lewdster female, he’d throw her overboard with the baby in her arms. Lightskirt and babe, they were in this together and they would die together, rot them both.

The dream was pleasant, but if he thought too hard about ways of turning it into reality, his stomach cramped and his head ached as if his skull had been cleaved. The moment he wanted to speak to anyone about Heron, his words dried up in his mouth, or turned to paeans in praise of the man. He’d discovered it was better to say nothing.

Sometimes he wondered about the lascar in his crew too. After all, he was a Va-forsaken nut-skin. Maybe he ought to throw him overboard, just in case. He closed his eyes and considered the idea. Voster and Fels, two of the ship’s swabbies: they were a couple of rogues who could make an accident happen. If he paid them enough, they’d even resist the temptation to wag their tongues about it afterwards.

Tempting, but no. Ardhi the lascar was a blistering good sailor. The way he scampered about the rigging in the roughest of weather like a giddy-brained spider! Besides, he and Heron were teaching the crew and the factors how to speak Pashali. If he did rid the ship of Heron, he’d need Ardhi alive to teach or they’d be at a disadvantage in spice negotiations. Better still, the lascar came from the nutmeg islands, and knew all about the paradise birds. He hadn’t managed to pry much out of the man yet, but he would. There were ways.

His fingers aching with nebulous desire, he forced himself to thread the plume back into the bambu. He flattened his hands on the desk, waiting for his fingers to cease their trembling.

“Banstel!” he roared.

The cabin door opened immediately and his cabin boy stepped inside. The lad had finally understood it was best not to keep the Commander of the Fleet waiting. Unfortunately, his hair was stuck with what looked to be hay and his shoes were filthy.

“You smell like a goat!” he snapped. “Next time you come in here looking like a street urchin, your backside will be striped and you’ll be sleeping on your stomach for a week. Understand?”

“Aye, sir.”

“Tell Mynster Yonnar Cultheer to report here immediately. Then bring us a carafe of rum cider, nicely mulled.”

Forgetting to acknowledge the order verbally, the lad scurried out. The goosecap; his mind was as unkempt as his appearance!

While he was waiting, Lustgrader reread the sealed orders he’d received just before they sailed from Ustgrind. Not for the first time, he had to resist the urge to crumple them up and toss them into the sea. Yonnar Cultheer wouldn’t like them, and Yonnar was the Merchant of the Fleet, the representative of the Company’s power aboard.

Banstel, now less tousled but still smelling of goat, delivered the jug of warmed cider at the same time as the black-clad merchant settled into the larger of the cabin’s two chairs. Lustgrader waved the boy out and half-filled two pewter mugs himself. Retrieving his shaker of ground nutmeg from its locked cabinet, he sprinkled a generous taste on top of the liquid.

“Clove, cinnamon, dried apple, nutmeg,” he said, inhaling the steam from his own drink after handing Cultheer his mug. “Not too many people can afford a luxury like this, eh, Mynster Cultheer? One of the few pleasures of being a sea captain who has sailed to the Spicerie and back.”

“Indeed.”

His agreement was without any inflection of enthusiasm and Lustgrader gave an inward sigh. Merchants could be tiresome. Unimaginative, sober men, they tended to put the Company’s interests ahead of everything, including the well-being of the ship’s officers and crew.

He chose his words carefully. “I want to speak to you about some instructions I received, signed and sealed by Regal Vilmar, and written, I believe, by His Grace, personally.” He picked up the letter from his desk. “These instructions are of a highly confidential nature. You can pass on the information to your factors with the understanding that if they say a word to anyone else, either on board ship or on land, the punishment will be severe. A matter of treason.”

Yonnar’s eyebrows rose. “You intrigue me. And I wonder why you inform me of this only now?”

He ignored the implied criticism. “We are instructed to make the procurement of more plumes of the paradise bird our primary concern, taking precedence over the acquisition of spices. They are to be considered the property of the Basalt Throne and the Lowmeer Spicerie Trading Company will be reimbursed accordingly.”

In shock, Cultheer dropped his mug on the desk, splashing liquid, and sat bolt upright. “What? Is this a jest? Commander, surely His Grace can’t be serious.”

“Regal Vilmar is not renowned for his levity, and you should watch your tongue.”

“Of course. You caught me by surprise.” Flustered, he mopped at the spilled drink with his pocket kerchief. “But this is an expedition privately funded by the merchant shipping companies of Lowmeer. They’ve all invested a great deal of money and will never countenance placing more importance on feathers than on spices! How could the Regal possibly reimburse the fortune we would lose?”

“Allow me to finish,” Lustgrader said, tone cold even as he revelled in the man’s discomfiture. “We are to buy or seize as many feathers as possible and keep them in good order under lock and key. No other member of this expedition is to be permitted to own or keep such plumes, on pain of summary execution. Plumes are to be delivered directly to the Regal and handled only with gloved hands.” He stared at Cultheer. “Mynster, these are orders from our monarch, not suggestions.”

Cultheer took a deep, controlling breath before he replied. “I can’t tell my factors to spend their time shooting and plucking birds!”

“I don’t think that would be a solution, either. The factors need to devote their whole attention to the buying of spices. I just want you to be aware that in order to please the Regal, we have to return with a great many feathers.”

Cultheer shook his head in a puzzled fashion. “Why does he want them? They may look pretty on an Ardronese lady’s hat, but our Va-fearing women are not so foolishly frivolous! No one in Lowmeer is going to pay a price that matches a picul of spices. We are not overdressed peacocks like the Ardronese. Does His Grace not realise one small sack of quality cloves or nutmeg would buy a man a manor house on Godwit Street?”

Lustgrader shrugged. “I do not question my liege lord. Unfortunately for us, the men who killed the bird on my last voyage are dead. They didn’t make it back to Lowmeer. No one knows exactly how they got the bird, or whether there were more such creatures out there. Consider this too: the islanders came after us, all the way from Chenderawasi Island to the port of Kotabanta, on Serinaga Island, just to demand the return of the plumes! They even said our men had killed the Raja of the islands, but my sailors strongly denied that. They swore it before the ship’s cleric, and I’ve no reason to doubt their truth.”

Cultheer snorted. “There might have been a good reason for them to lie. If they’d really murdered the ruler of the island, you would have had to give them up to island justice. I’ve no doubt the islanders’ vengeance would have been savage.”

“I’d rather believe God-fearing men than Va-forsaken nut-skins!” he snapped. “However, the fact that they came such a long distance to demand we deliver up these men for whatever they did, together with the plumes they had, indicates that the Chenderawasi people are not likely to cooperate and supply us with more plumes, no matter how much we offer. Probably the birds are sacred, or some such foolish superstition. I have tried to pry more out of that Va-forsaken lascar we have on board, but you’d think he didn’t understand a word I said for all I could get out of him.”

“So what’s your solution?” Cultheer had calmed enough to sip his drink, and his eyes lit up as he savoured the flavour.

“I suggest that we recruit some natives from another island, Serinaga perhaps, and bring them with us to Chenderawasi, where they can go bird-hunting with some of our swabbies. The Regal must get what he wants, and we must obtain our spices.”

Cultheer frowned unhappily and fiddled with his mug. “Yes, but what if your sailors really did kill the Raja? Or perhaps I should say, what if the islanders believe they did? They won’t welcome our return. We are more likely to be met with spears and clubs.”

The cold of doubt in the pit of Lustgrader’s stomach kept him silent.

“Pity we have to go to Chenderawasi at all,” Cultheer said. “We could buy their nutmeg in Kotabanta, albeit for a higher price.”

“We have half a dozen factors there on Chenderawasi, don’t forget–their warehouses filled with nutmeg and mace! Or so I trust. But we don’t have a choice now, anyway. The Regal’s instructions are clear.”

“I mislike this, captain. It appears we have two masters in Lowmeer, one the Company and the other our monarch, and we have to please both of them. Not to mention Chenderawasi savages enraged by the death of birds.”

“We are five armed ships, Cultheer. More fire power than any previous fleet. Our factors there are well armed. These islanders have nothing but a few daggers or spears. I do feel, however, that the more we know about them and their birds, the better our trade will be.”

There, he’d planted the suggestion without mentioning Factor Heron. Now, Cultheer, it’s up to you. Use your brains, man…

“I could lever some more information out of the lascar,” Cultheer suggested. “Or better still, ask someone else to do it. Factor Heron. He’s always chatting to the dusky fellow. Said it’s because he’s interested in learning the language of the islands.”

Lustgrader smiled. “You do that. Find out all you can. About… about…” He ached to tell Cultheer exactly what to say, but the Va-damned sorcery wouldn’t let him. He raised his mug in a toast instead. “Drink to our success. Spice–and feathers!”

He doubted Heron would tell Cultheer or anyone else the truth about the power of the plumes, but sometimes you learned a lot from people trying to hide something. Most of all, he just wanted Heron to know that the traders of Lowmeer would be hunting the birds, that therefore others knew how the plumes could be used. He wanted that Va-cursed factor to feel the fear of the stalked, because he was being stalked. And one day, he, Gunrad Lustgrader, would find a way to send Factor Reed Heron to perdition where he belonged.

“Keel-raked,” he said aloud, after the merchant had left. To his ears, the words were rich with promise. He took a deep breath and smiled.

“How can Ardhi’s dagger be some kind of… sorcerous blade with the power to influence the weather? Saker, that’s curdled crazy.”

Sorrel hugged Piper a little closer to her breast, her disbelief warring with her fear that he was right. Around them, the life of the ship continued, but no one noticed her. She was blurred into the background of sand-filled fire buckets, and Saker was attempting to look as if he was dozing in a patch of sunlight.

Sunlight, at last. She was so fed up with rain and cold and cloud. It had been the weather that had imprisoned her, not Captain Lustgrader’s orders that she was to remain below and not converse with the sailors or the factors. Now it seemed the weather had been the least of her problems, for Saker was talking of something she had not wanted to think about at all: Va-forsaken magic.

She had seen it in action. She’d seen the way the Chenderawasi plume had entranced Captain Lustgrader. She’d even once briefly glimpsed another world because of Ardhi’s dagger–but, oh, how hard it was to acknowledge that she could be powerless in the face of something so alien and utterly without conscience.

“It was responsible for the storms? Just so I could not be landed anywhere on the Ardronese coast as we’d planned?” She snorted. “I’ve never heard of anything so absurd! Look at me. I’m a nobody. I started life as a yeoman’s daughter, then a landsman’s wife, and finally a servant hovering somewhere between the status of a lady-in-waiting and a despised chambermaid.”

“You’re not a nobody, not to me,” he said.

Once her heart would have lurched to hear that; once she would have blushed with pleasure, but not now. He was the one whose actions had brought her to virtual imprisonment on this ship and it rankled still. “Well, that’s sweet of you to say so, but it doesn’t change anything.”

“If it wasn’t you the kris wanted on board, then it was Piper.”

“That’s silly. She’s just a baby.” But the thought that it could be true tore her fragile equanimity to shreds. Appalled, she started shaking. “Because she’s a twin? Or because she’s Mathilda’s child?”

“How can any of us know why? Maybe Va-forsaken sorcery is doing this to prevent us getting her to the Pontifect.” He glanced at her. “You’re shivering! Are you cold?”

She shook her head, but her st

The mast creaked under the strain of wind-filled sails, the tang of salt and wet canvas saturated the air, but in the crow’s nest, memory had snared Ardhi in his past. He smelled the smoke of mangrove charcoal burning in the kilns and heard the hammering in the forges of the metalworkers’ village. His thoughts lingered in that other world, recalling the greying attap roofs of the houses on stilts and the rows of fish drying on the racks in the sun.

His grip on the railing in front of him tightened as he remembered the day he’d gone there to see the blademaster, the empu Damardi. He’d been sick with guilt and shame. His pounding heart had matched the sound of the hammers; the whiff of molten metal had tasted bitter to his tongue.

With clammy fingers, he’d straightened his loose jacket, brushed a streak of dirt from the hem of his pantaloons and checked for any untidy strands of hair escaping from under his cloth headband. He’d made sure that his kris, his father’s coming-of-age gift, was neatly tucked into the waist of the sampin wrapped around his hips. Finding nothing that would hint at disrespect for the man he was about to visit, he’d walked on past the lesser smiths until he came to the house of Damardi, the greatest krismaker of all.

Once there, he did not mount the steps to the serambi, the raised porch, as a normal visitor might. Instead, he’d knelt on the bare swept earth in front of the house. He’d taken the plume he carried from its sheath of protective bambu and laid it on the ground. In the mango tree overhead, the bird they called the macaque’s slave scolded its noisy warning at his intrusion.

The villagers went about their business, muttering to each other while they ignored him with calculated insult as he knelt there in the heat. Remorse suffused his face and neck with red. They all knew his careless words had brought the unimaginable to the Pulauan Chenderawasi. He’d told the pale sailors of paradise birds, and they’d come a-hunting.

They’d shot Raja Wiramulia with their guns, killed him for the golden plumes of his regalia even though they knew nothing of their true sakti, the Chenderawasi magic with which they were imbued.

Kneeling there in the metalmaker’s village, mortified, Ardhi wanted to die.

The village boys were less mannerly than their elders. They spat on him and whispered as they passed by, “Betrayer. Traitor. Moray, moray, moray!”

He shuddered and hung his head at the insult. The despised moray eel was the hated assassin of the reef, darting out of its dark crevasse to seize unwary prey.

An hour passed before Damardi stepped on to the serambi and placed his hands on the railing. “Who comes to speak to the bladesmith?” he asked, looking down on him. “You, young Ardhi? How dare you bring the Raja’s plume here, still stained with his blood!”

“The Rani bade me ask for a kris to be made, empu. Who else is skilled enough to craft such a blade?” He picked up the plume and held it in both hands, offering it to the old man. Damardi would need some of its barbules to fold into the metal.

Yet the blademaster swelled with rage. “Such a kris is borne only by a warrior-hero in the service of the Chenderawasi. Are you such a hero? Are you even a warrior?” His scorn was scarifying and his grief seared.

Yet Ardhi couldn’t look away. “Empu, it is the Rani’s wish.”

Tears slid down the creases of Damardi’s wrinkled cheeks to pool at the corners of his mouth. He made a gesture with his hand without turning around and, in answer, his granddaughter emerged from the door behind him. Lastri.

Lastri, with her long black hair and lithe body, her shoulders bare above the tight wrap of her breast cloth. Lastri, whom he had loved so well. Lastri, who’d swum naked with him in the lagoon by night, and lain in his arms on the sand after they’d made love by moonlight. Lastri, who had pledged herself to him, just as he had sworn his love for her.

Now she carried half a coconut shell cupped in both hands and the curve of her hips shivered him with its reminder of all he’d lost.

“The Rani sent me the blood of the Raja,” Damardi said, his voice cracking as he gestured at the contents of the shell. “This will be used to damask the blade.” His unflinching gaze fixed on Ardhi’s like the eye of a sea-eagle on its prey. “I must obey Rani Marsyanda. I will make this kris, although every song in my soul screams at me that you are unworthy of it. Leave the plume. Return after two moons, and the kris will be ready.”

“Two months is too long, empu. The kris is needed now.”

“Revenge can always wait.”

He licked dry lips. “It is not needed for revenge. That, I could achieve with my bare hands.”

“Then why?”

“The pale men still have the other plumes. They took them on board their ship and sailed away. I need the kris to follow the regalia, that I might find and return the plumes to their rightful place.”

Lastri gasped, her eyes widening. Damardi’s knuckles whitened as his grip on the porch railing tightened. “These pale men, these ugly banana skins, do they know the power lurking within the plumes?” he asked.

“No.”

“At least you had a rice grain of wisdom left in your empty, traitorous skull.”

He hung his head in silence.

“But a kris containing the sakti, the magic of the Chenderawasi? Such a kris cannot be made in an hour, or a day, or a single moon. The metal must be folded and refolded, the blade must be waxed and soaked and damasked to its edge. Every step must be perfect, otherwise how can it be endowed with its sakti? Two months, Ardhi.”

“And there’s the hilt,” Lastri murmured. “Who is to craft and carve the hilt?”

“The Rani. She will use…” But Ardhi couldn’t finish the sentence.

“I know what she will use,” the old man replied, scowling. His eyes glistened. “And she will have already cut what is needed from the body of her husband.”

With those words, Damardi appeared to shrink before Ardhi’s eyes. The wrinkles on his cheeks burrowed deeper and his eyes shadowed darker under the heavy overhang of his brows. “Very well,” he whispered. “I will craft a Chenderawasi kris, but to do it in seven days, a price will have to be paid.”

“I will pay it.”

“You do not know what it is.”

“Empu, if a price has to be paid, then it is mine to pay, and it shall be done.”

“Indeed.” Damardi nodded. “You will stay with me for those seven days. Your strength will aid me. But when it comes to the power of a Chenderawasi kris, your promise to sacrifice your life will be the spark that awakens the Raja’s blood and the plume-gold of his regalia. There is no other way. For without a sacrifice, the sakti of this kris will rouse too slowly to give it life.”

Grief-stricken, Ardhi bowed his head. “I need to live, empu. I need to live to seek, find and return the plumes.”

Damardi frowned, considering. “Then the day you return with the plumes will be the day of your sacrifice. That promise and those undertakings I will fold into the blade. Your blood to be spilt, and your life freely given to the blade of this very kris. If you do not return the feathers, then the kris itself will turn on you in punishment and take your life no matter where you are. You have no future beyond your quest, Ardhi.”

He nodded, his grief cold with fear and rock-hard in his breast. The time of his death had been decreed. So be it. Yet he wept at the thought.

He was only eighteen.

Glancing at Lastri, he winced. Her face was a mask, her eyes dulled with grief, but her stance said something else. She was enraged, furious at him for what he had destroyed: their future together.

“Now go,” Damardi said. “Build a fire in my forge, so we may heat the metal. I have the best Pashali iron, and we will mix it with the dark-silver sky iron from the heavens, collected long past in the mountains. We shall add the root of the graveyard tree and the leaves of the tree of life. This kris will have a bird’s-eye damask at the point and the stem, to ensure that its future is auspicious. Its power will carry the sakti of the islands across the seas to aid your task.” A tear trickled down his cheek. “You are not worthy of such a blade.”

Pulauan Chenderawasi. The nutmeg islands.

Agony to have the memories play again and again before his eyes–yet how to stop them?

Perhaps it is punishment, Ardhi thought. Perhaps it was all just to remind him that even if lives were ruined, he had to believe in the rightness of what the kris was doing. The path of the sakti of the Chenderawasi was always true.

He looked up at the sails of the Spice Winds and dragged his thoughts back to the present. He had to understand why the dagger had brought the four of them–Saker, Sorrel, Piper and himself–together on board this ship on its way to the Spicerie.

Splinter it, though, now is not the time to think about it. He was on lookout duty. He turned his attention to the ocean.

On the horizon ahead, the Regal’s aging galleon, Sentinel, wallowed along with its impressive array of cannons. Keeping pace to either side of Spice Winds were the two other new fluyts designed for spice cargoes; and far behind, with a topmast splintered, limped the elderly carrack Spice Dragon. It was a miracle that on this, the first day of watery sunshine they’d had since leaving Ustgrind, the Lowmian fleet was still together. It had taken a whole moon month to emerge from the storm-scoured waters of the Ardmeer Estuary, followed by fourteen more miserable days of appalling weather as the fleet rounded the Yarrow Islands and lost sight of land.

His mind began to wander again, to a sun-sparkled sea where the waters were brighter, the skies a deeper blue. Even the seabirds there spoke other tongues…

The kris at his hip slithered in its sheath, pushing against his thigh. He jerked in surprise. The blade hadn’t as much as glinted for weeks, let alone moved of its own volition. He drew it out, and the point swung downwards. He looked through the slats of the floor of the crow’s nest to see what had prompted its awakening.

Sorrel, who rarely left the hastily converted storage cuddy that was her cabin, was on the weather deck with Piper, glamoured so none of the sailors could see either of them.

Ardhi felt a stab of sympathy at her loneliness. Captain Lustgrader had decreed she stay away from the crew at all times–except for Banstel. Barely thirteen years old, the ship’s boy milked the goats, washed Piper’s swaddling and brought Sorrel’s meals to her.

He might have known that she would sneak up on deck now that the weather was better. She had courage and determination, that woman. He admired the set of her shoulders, the lift of her chin at any hint of adversity, the steel in her gaze when she was threatened. What he didn’t understand was why the dagger’s sakti had manipulated the weather to ensure she couldn’t leave the ship, as she’d wanted. As for Piper, the baby–he couldn’t fathom who she was at all, or why she was here.

He fingered the hilt of the dagger, taking courage from the feel of the Raja’s bone beneath his fingers before slipping it back into its sheath. He should have felt satisfied. Those bulging sails around him were filled with cold northerly winds driving the ship towards the Summer Seas.

He was heading home. The three pillaged plumes of the Raja’s regalia were safe in his baggage, and the fourth feather, the one he had been granted by the Rani to aid his task, was close by in Commander Lustgrader’s hands. He could retrieve it once Saker no longer needed to use its power to coerce Lustgrader.

Sri Kris had prevailed in the Va-cherished Hemisphere, had done everything that had been required of it.

Except kill him.

Skies above, why did he find that so hard to accept? He’d agreed to it! Yet his spirit rebelled and his thoughts darkened with defiant anger. He wasn’t eighteen any longer, but he wanted to lash out at his fate, wanted to do anything just to go on living.

Down on the deck, Sorrel looked up at him. Her gaze locked on his, and her mouth curved up in a smile. Without thinking, he smiled back and felt a sudden surge of desire. For her perhaps–or maybe just a longing to find desire and passion in a woman’s arms again, someone, somewhere, before he died.

The ship’s bell rang. His watch in the crow’s nest over, he scanned the horizon one last time. Spice Dragon was falling out of sight behind. Not a good idea to scatter too widely, not when Ardronese privateers might be waiting to pick them off, although that was unlikely while their holds were still empty of spices.

As he headed down the shrouds, a wind-rover approached the ship, skimming the waves. He halted his descent to watch, fascinated by its effortless grace as it banked. Its wingspan was greater than his own outstretched arms. It rose to cross the ship just over the mizzen mast, then swung around behind the stern, only to return at a lower level coasting towards the aft deck. Saker was standing at the stern rail, and Ardhi didn’t need to be told he was calling the bird in. It wasn’t the first time either; the man had done this at least once before on this journey, perhaps more.

Witan Saker Rampion, masquerading as Lowmian Factor Reed Heron. There’s more to you and your witchery than you guess.

The wind-rover matched its speed to the ship, cruising, spreading the feathers of its tail and dropping its legs, flying lower and lower until it touched down on the decking. It folded its wings over its back and ruffled them uneasily, then lowered its head to hiss its aggression.

The helmsman, with his back to the raised poop at the stern, didn’t see what was happening, but other sailors working further along the deck noticed and gaped. Saker knelt beside the gigantic bird, stroked its head and neck until it relaxed, then bent to do something to one of its legs. From above, Ardhi couldn’t see exactly what, but a few moments later the bird rose from the deck, its spread wings easily catching the lift of the wind. It banked away from the ship and vanished between the swell of the waves.

Ardhi climbed on down to tell the officer of the watch about the lagging Spice Dragon.

Gunrad Lustgrader, commander of the fleet of the Lowmian Spicerie Trading Company and captain of Spice Winds, sat at the desk in his cabin. Lying in front of him, next to an empty length of bambu, was the paradise-bird feather Reed Heron had gifted him. Billows of gold and orange and red enticed him to stroke the plume, to revel in the sensuous thrill of its touch. The glow of its ambient light was warm and welcoming. Magical.

For a moment he was transported back to the islands of the Summer Seas and inhaled again the perfume of the flowering cinnamon and the musky scent left around the villages at night by roving civets. The warm coral sands scrunched underfoot once more and the glory of birdsong filled his ears, sounds so ethereal that tears pricked his eyelids.

He wrenched himself into the present.

Scupper that. The plume was uncanny and it held him in thrall. He knew that and fought it, so why was it a battle where victory always seemed just out of reach?

On his last voyage, he’d seen men in Kotabanta happily disintegrate into drooling fools after inhaling the smoke of burned tree sap. Such madness! The rational part of his mind told him he was like that, drugged, no longer in command of his own destiny, captured–not by smoke–but by cursed sorcery from the Va-forsaken Hemisphere.

That bastard scut, Heron. He’s to blame.

Appalling snatches of the day they’d met, not fully recalled and never quite in focus, floated through his memory. He couldn’t dismiss them as inaccurate; they stayed, nagging, an ache eroding his sanity.

Tolbun, first mate, had even bluntly told him that the whole ship’s company wondered at the way he fawned before Heron, and puzzled over why he’d ever allowed that flirt-skirt and her squalling baby on board.

He knew his behaviour was deranged, yet couldn’t change it.

One day soon, Factor Heron, I’ll see you keel-raked, your skin shredded on the barnacles, your back flayed to the bone, and if you survive that, I’ll hang you from the yardarm. As for that lewdster female, he’d throw her overboard with the baby in her arms. Lightskirt and babe, they were in this together and they would die together, rot them both.

The dream was pleasant, but if he thought too hard about ways of turning it into reality, his stomach cramped and his head ached as if his skull had been cleaved. The moment he wanted to speak to anyone about Heron, his words dried up in his mouth, or turned to paeans in praise of the man. He’d discovered it was better to say nothing.

Sometimes he wondered about the lascar in his crew too. After all, he was a Va-forsaken nut-skin. Maybe he ought to throw him overboard, just in case. He closed his eyes and considered the idea. Voster and Fels, two of the ship’s swabbies: they were a couple of rogues who could make an accident happen. If he paid them enough, they’d even resist the temptation to wag their tongues about it afterwards.

Tempting, but no. Ardhi the lascar was a blistering good sailor. The way he scampered about the rigging in the roughest of weather like a giddy-brained spider! Besides, he and Heron were teaching the crew and the factors how to speak Pashali. If he did rid the ship of Heron, he’d need Ardhi alive to teach or they’d be at a disadvantage in spice negotiations. Better still, the lascar came from the nutmeg islands, and knew all about the paradise birds. He hadn’t managed to pry much out of the man yet, but he would. There were ways.

His fingers aching with nebulous desire, he forced himself to thread the plume back into the bambu. He flattened his hands on the desk, waiting for his fingers to cease their trembling.

“Banstel!” he roared.

The cabin door opened immediately and his cabin boy stepped inside. The lad had finally understood it was best not to keep the Commander of the Fleet waiting. Unfortunately, his hair was stuck with what looked to be hay and his shoes were filthy.

“You smell like a goat!” he snapped. “Next time you come in here looking like a street urchin, your backside will be striped and you’ll be sleeping on your stomach for a week. Understand?”

“Aye, sir.”

“Tell Mynster Yonnar Cultheer to report here immediately. Then bring us a carafe of rum cider, nicely mulled.”

Forgetting to acknowledge the order verbally, the lad scurried out. The goosecap; his mind was as unkempt as his appearance!

While he was waiting, Lustgrader reread the sealed orders he’d received just before they sailed from Ustgrind. Not for the first time, he had to resist the urge to crumple them up and toss them into the sea. Yonnar Cultheer wouldn’t like them, and Yonnar was the Merchant of the Fleet, the representative of the Company’s power aboard.

Banstel, now less tousled but still smelling of goat, delivered the jug of warmed cider at the same time as the black-clad merchant settled into the larger of the cabin’s two chairs. Lustgrader waved the boy out and half-filled two pewter mugs himself. Retrieving his shaker of ground nutmeg from its locked cabinet, he sprinkled a generous taste on top of the liquid.

“Clove, cinnamon, dried apple, nutmeg,” he said, inhaling the steam from his own drink after handing Cultheer his mug. “Not too many people can afford a luxury like this, eh, Mynster Cultheer? One of the few pleasures of being a sea captain who has sailed to the Spicerie and back.”

“Indeed.”

His agreement was without any inflection of enthusiasm and Lustgrader gave an inward sigh. Merchants could be tiresome. Unimaginative, sober men, they tended to put the Company’s interests ahead of everything, including the well-being of the ship’s officers and crew.

He chose his words carefully. “I want to speak to you about some instructions I received, signed and sealed by Regal Vilmar, and written, I believe, by His Grace, personally.” He picked up the letter from his desk. “These instructions are of a highly confidential nature. You can pass on the information to your factors with the understanding that if they say a word to anyone else, either on board ship or on land, the punishment will be severe. A matter of treason.”

Yonnar’s eyebrows rose. “You intrigue me. And I wonder why you inform me of this only now?”

He ignored the implied criticism. “We are instructed to make the procurement of more plumes of the paradise bird our primary concern, taking precedence over the acquisition of spices. They are to be considered the property of the Basalt Throne and the Lowmeer Spicerie Trading Company will be reimbursed accordingly.”

In shock, Cultheer dropped his mug on the desk, splashing liquid, and sat bolt upright. “What? Is this a jest? Commander, surely His Grace can’t be serious.”

“Regal Vilmar is not renowned for his levity, and you should watch your tongue.”

“Of course. You caught me by surprise.” Flustered, he mopped at the spilled drink with his pocket kerchief. “But this is an expedition privately funded by the merchant shipping companies of Lowmeer. They’ve all invested a great deal of money and will never countenance placing more importance on feathers than on spices! How could the Regal possibly reimburse the fortune we would lose?”

“Allow me to finish,” Lustgrader said, tone cold even as he revelled in the man’s discomfiture. “We are to buy or seize as many feathers as possible and keep them in good order under lock and key. No other member of this expedition is to be permitted to own or keep such plumes, on pain of summary execution. Plumes are to be delivered directly to the Regal and handled only with gloved hands.” He stared at Cultheer. “Mynster, these are orders from our monarch, not suggestions.”

Cultheer took a deep, controlling breath before he replied. “I can’t tell my factors to spend their time shooting and plucking birds!”

“I don’t think that would be a solution, either. The factors need to devote their whole attention to the buying of spices. I just want you to be aware that in order to please the Regal, we have to return with a great many feathers.”

Cultheer shook his head in a puzzled fashion. “Why does he want them? They may look pretty on an Ardronese lady’s hat, but our Va-fearing women are not so foolishly frivolous! No one in Lowmeer is going to pay a price that matches a picul of spices. We are not overdressed peacocks like the Ardronese. Does His Grace not realise one small sack of quality cloves or nutmeg would buy a man a manor house on Godwit Street?”

Lustgrader shrugged. “I do not question my liege lord. Unfortunately for us, the men who killed the bird on my last voyage are dead. They didn’t make it back to Lowmeer. No one knows exactly how they got the bird, or whether there were more such creatures out there. Consider this too: the islanders came after us, all the way from Chenderawasi Island to the port of Kotabanta, on Serinaga Island, just to demand the return of the plumes! They even said our men had killed the Raja of the islands, but my sailors strongly denied that. They swore it before the ship’s cleric, and I’ve no reason to doubt their truth.”

Cultheer snorted. “There might have been a good reason for them to lie. If they’d really murdered the ruler of the island, you would have had to give them up to island justice. I’ve no doubt the islanders’ vengeance would have been savage.”

“I’d rather believe God-fearing men than Va-forsaken nut-skins!” he snapped. “However, the fact that they came such a long distance to demand we deliver up these men for whatever they did, together with the plumes they had, indicates that the Chenderawasi people are not likely to cooperate and supply us with more plumes, no matter how much we offer. Probably the birds are sacred, or some such foolish superstition. I have tried to pry more out of that Va-forsaken lascar we have on board, but you’d think he didn’t understand a word I said for all I could get out of him.”

“So what’s your solution?” Cultheer had calmed enough to sip his drink, and his eyes lit up as he savoured the flavour.

“I suggest that we recruit some natives from another island, Serinaga perhaps, and bring them with us to Chenderawasi, where they can go bird-hunting with some of our swabbies. The Regal must get what he wants, and we must obtain our spices.”

Cultheer frowned unhappily and fiddled with his mug. “Yes, but what if your sailors really did kill the Raja? Or perhaps I should say, what if the islanders believe they did? They won’t welcome our return. We are more likely to be met with spears and clubs.”

The cold of doubt in the pit of Lustgrader’s stomach kept him silent.

“Pity we have to go to Chenderawasi at all,” Cultheer said. “We could buy their nutmeg in Kotabanta, albeit for a higher price.”

“We have half a dozen factors there on Chenderawasi, don’t forget–their warehouses filled with nutmeg and mace! Or so I trust. But we don’t have a choice now, anyway. The Regal’s instructions are clear.”

“I mislike this, captain. It appears we have two masters in Lowmeer, one the Company and the other our monarch, and we have to please both of them. Not to mention Chenderawasi savages enraged by the death of birds.”

“We are five armed ships, Cultheer. More fire power than any previous fleet. Our factors there are well armed. These islanders have nothing but a few daggers or spears. I do feel, however, that the more we know about them and their birds, the better our trade will be.”

There, he’d planted the suggestion without mentioning Factor Heron. Now, Cultheer, it’s up to you. Use your brains, man…

“I could lever some more information out of the lascar,” Cultheer suggested. “Or better still, ask someone else to do it. Factor Heron. He’s always chatting to the dusky fellow. Said it’s because he’s interested in learning the language of the islands.”

Lustgrader smiled. “You do that. Find out all you can. About… about…” He ached to tell Cultheer exactly what to say, but the Va-damned sorcery wouldn’t let him. He raised his mug in a toast instead. “Drink to our success. Spice–and feathers!”

He doubted Heron would tell Cultheer or anyone else the truth about the power of the plumes, but sometimes you learned a lot from people trying to hide something. Most of all, he just wanted Heron to know that the traders of Lowmeer would be hunting the birds, that therefore others knew how the plumes could be used. He wanted that Va-cursed factor to feel the fear of the stalked, because he was being stalked. And one day, he, Gunrad Lustgrader, would find a way to send Factor Reed Heron to perdition where he belonged.

“Keel-raked,” he said aloud, after the merchant had left. To his ears, the words were rich with promise. He took a deep breath and smiled.

“How can Ardhi’s dagger be some kind of… sorcerous blade with the power to influence the weather? Saker, that’s curdled crazy.”

Sorrel hugged Piper a little closer to her breast, her disbelief warring with her fear that he was right. Around them, the life of the ship continued, but no one noticed her. She was blurred into the background of sand-filled fire buckets, and Saker was attempting to look as if he was dozing in a patch of sunlight.

Sunlight, at last. She was so fed up with rain and cold and cloud. It had been the weather that had imprisoned her, not Captain Lustgrader’s orders that she was to remain below and not converse with the sailors or the factors. Now it seemed the weather had been the least of her problems, for Saker was talking of something she had not wanted to think about at all: Va-forsaken magic.

She had seen it in action. She’d seen the way the Chenderawasi plume had entranced Captain Lustgrader. She’d even once briefly glimpsed another world because of Ardhi’s dagger–but, oh, how hard it was to acknowledge that she could be powerless in the face of something so alien and utterly without conscience.

“It was responsible for the storms? Just so I could not be landed anywhere on the Ardronese coast as we’d planned?” She snorted. “I’ve never heard of anything so absurd! Look at me. I’m a nobody. I started life as a yeoman’s daughter, then a landsman’s wife, and finally a servant hovering somewhere between the status of a lady-in-waiting and a despised chambermaid.”

“You’re not a nobody, not to me,” he said.

Once her heart would have lurched to hear that; once she would have blushed with pleasure, but not now. He was the one whose actions had brought her to virtual imprisonment on this ship and it rankled still. “Well, that’s sweet of you to say so, but it doesn’t change anything.”

“If it wasn’t you the kris wanted on board, then it was Piper.”

“That’s silly. She’s just a baby.” But the thought that it could be true tore her fragile equanimity to shreds. Appalled, she started shaking. “Because she’s a twin? Or because she’s Mathilda’s child?”

“How can any of us know why? Maybe Va-forsaken sorcery is doing this to prevent us getting her to the Pontifect.” He glanced at her. “You’re shivering! Are you cold?”

She shook her head, but her st

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved