- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

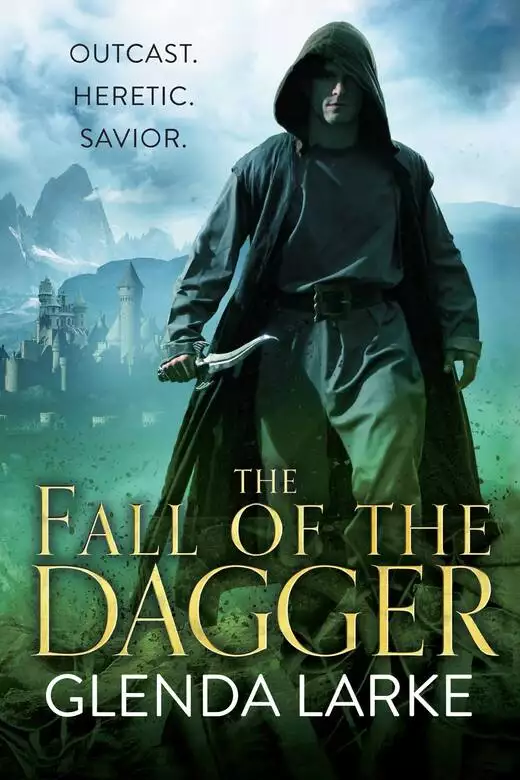

Synopsis

Sorcerers, pirates, and thieves collide in this thrilling conclusion to Glenda Larke's epic fantasy adventure series, The Forsaken Lands.

Release date: April 19, 2016

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 457

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

The Fall of the Dagger

Glenda Larke

Pontifect Fritillary Reedling stood on the terrace overlooking the white-walled city of Vavala, her gaze fixed on the most distant roofs. When a breeze stirred the strands of her grey hair straying from the confines of her coif, she brushed them away from her face in irritation. Next to her, Barden, her private secretary, leaned against the balustrade for support, his breathing as noisy as the huffing of bellows. Waiting behind them were the only two remaining members of her guard, Hawthorn and his aide, Vetch, neither of them quite young enough, or fit enough, to provide her with any protection other than the wisdom of advice.

A cerulean sky was almost cloudless. Spiralling up into the blue, a songbird poured a joyous melody into the spring air to entice his mate and threaten his rivals.

A perfect day, a day to feel good about being alive.

Except it held no promise that any of them would live long enough to see another sunrise.

A puff of smoke rose above the distant buildings, silent and silky white, followed a moment later by an explosion that overwhelmed the birdsong and tore the air apart. The foundations below their feet quivered. A distant cloud of dust and debris lifted into the air, blossomed outwards with the beauty of an unfolding flower, then rained down on the city with an ugly roar. Fritillary winced and looked away.

“Cannon,” Vetch said unnecessarily.

“It was only a matter of time,” said Hawthorn. “The sole unanswered question is where they got them.” Cannon were rare in the Va-cherished lands.

“Raided the gun decks of one of the king’s galleons?” Vetch suggested.

“Imported by mastodon across the ice from Pashalin, more likely,” Fritillary said. “With the gunpowder to fire them.”

“Va-less curs.” Another unnecessary mutter from Vetch.

Silence returned.

Below, the streets were eerily empty, the houses shuttered, the chimneys cold, the doors closed. The only living thing within her sight was a cat, which a moment ago had been sunning itself on a doorstep with undisturbed aplomb. Now it was scrabbling up a wall in fright. In the distance to the north, another rumble of cannon fire was followed by a brief silence as the world held its breath, then a second jarring, heart-wrenching impact that shattered her soul.

Her city. Her failure.

She had long since given the order for civilians to evacuate, to flee across the river to Staravale, leaving only those prepared to fight alongside the city guard and the soldiers of the Pontificate. Her soldiers.

In truth, she had asked them to die so that others could escape. So far, they had held the walls, but that wouldn’t last.

Another cannonball shot, another hit, another puff of dust and smoke, more birds rising with startled cries into the sky. By the sound of it, the besiegers only had several light cannon, but pound away at the northern gate for long enough, and it would eventually splinter. Lob explosive-filled balls over the wall and defenders would die.

We’ve lost.

So where are you, Va? Are we the Forsaken Lands now? She sighed. There she was, blaming Va. How ridiculous was that?

The minutes dragged by. More cannon fire, more sounds of a city falling, brick by brick, tile by tile. Man by man.

“Your Reverence, it’s time.” Hawthorn, nagging as usual. Unable to fight because of his failing eyesight, but still desperate to protect her.

“Not yet.”

“He’s right,” Barden said.

“Soon.” She couldn’t leave, not until she was sure all was lost. My city. My resplendent city.

In the street below, a horse swung into the main palace thoroughfare bearing a man in the uniform of her palace guard. They all watched in silence as he rode at a gallop into the forecourt through the open gate, halted his mount at the foot of the stairs to the terrace, then flung himself off to take the steps three at a time. A makeshift bandage on one of his arms partially covered a tattered sleeve drenched in blood.

He was young. Seventeen? Eighteen? Too young to have endured all he must have seen and done that day.

“Reporting from Captain Marsh,” he said when he reached them, the words pitched too high, just short of panic.

“What’s the latest?” She tried to sound calm, but rage and fear had tightened her throat until it ached.

His voice wavered as he answered. “The wall is breached to the north. The men are still fighting, street by street, but – it’s just a matter of time.”

“I can smell the burning.” Wood, and worse. They could see it now, too; a plume of smoke carrying showers of sparks upwards. Why would they burn the city? Didn’t he want to rule it, that sorcerous horror Fox? Valerian Fox. What good was a city to him if it was burned to the ground? “The shrine?” she asked. The lad would have passed it on his way to the palace. The city of Vavala had been built to encompass a spring that fed the River Ard and the Great Oak that grew there, the oldest and most sacred place in the whole Va-cherished Hemisphere, where the Way of the Flow and the Way of the Oak combined.

“Gone,” he whispered. He was choking, forcing the words out as he struggled to control his emotion. “There’s no sign of the oak.”

She nodded. It was the answer she’d expected. “Have faith. It will return when times are safe.” She patted his arm, despising herself for the futile pretension of both words and action, but she didn’t know what else to do. How could you comfort someone who had indeed put their faith in Va, and in their Pontifect, only to be let down so badly?

He looked at her, appalled, and she was pierced to the bone by his horror. He could not conceive of a world where the oak was not a constant, a place to turn to in troubled times.

By earth and oak, what have you done to him and others like him, Fritillary?

“The evacuation?” she asked, and wondered at the blandness of her tone.

“Th – those who wanted to leave have gone. The captain says you must go now. He doesn’t know how much longer he can hold against the Grey Lancers. The smutch—” He choked back a sob. “It makes men despair when they should be fighting. I saw—” He swallowed. “I saw grown men drop their swords and sink to their knees, weeping.”

“You’ve felt the smutch?”

“We all have.” He wiped tears from his begrimed face. “If Your Reverence had not sent the oak leaves, we would all have succumbed.”

She had ordered every guard to place a leaf against his chest; she’d had sacred acorns distributed, hoping that would grant them courage, but, dear Va, Prime Valerian Fox was at the gates and he had grown in power. She shuddered to think how. Lord Herelt Deremer of the Dire Sweepers had told her that Valerian gained his greatest strength by draining his own ill-begotten sons. Possibly Herelt was right. She’d certainly believed him earlier, when he’d told her Fox sucked the life from children in order to add to his own life force, leaving them to sicken and die of the Horned Plague.

She took a deep breath. “Tell the captain I am leaving now. Tell him there are no further orders; he is to do what he thinks is best. Tell him Va is with us all in the end, and every man who fights here today will be remembered for all time.”

But, oh, Va! Why have you not shown us how to combat this evil? What have we done that we are left so helpless?

Deceived by words, confused by the power of coercion and enticement that Prime Fox’s numerous sons possessed, men and boys had flocked to the Prime’s banner, like hens after a strutting rooster. Ordinary men made into willing, mindless automatons by sorcery. Even unseen guardians and shrine keepers, who were able to resist the coercion themselves, had been unable to combat the spreading evil. She had drained the coffers of the Pontificate in an effort to recruit and train the faithful, but there was only so much an ordinary man or woman could do when faced with sorcery. In desperation, she had swallowed her revulsion of all Lord Herelt Deremer stood for, and allied herself to him – but most of his resources and his men were in Lowmeer, not in the Principalities or the kingdom of Ardrone.

When the young guardsman had gone, she could not rid herself of the notion that she had sent him to his death. Bitterly, she accepted the truth of that thought, and turned to Hawthorn. “Sergeant, you and Vetch bring our packs to the postern door. Barden and I will meet you both there.”

As she and her secretary headed through the palace halls, their footsteps and the tap of his wooden staff echoing in the emptiness, she muttered, “I was not born for this. I am no warrior.”

“No one is born for war.”

For once, he was moving fast alongside her, even with his bent back. His liver-spotted hand clasped the head of his walking stick, using it with a driving purpose. She blinked, surprised at his turn of speed.

“All it would have taken was a word from you,” he said, and she heard condemnation in his tone. “You could have ordered those clerics blessed with witcheries to use them—”

“They would have lost their witcheries. Or died! Not now, Barden, not now.” They’d had this argument a hundred times over the past year. Was it moral to use a Va-given witchery to kill? All she’d been taught, all she’d believed in, had told her witcheries were to be used for good, that to use one to kill was not only wrong, but would result in the loss of the perpetrator’s witchery. While she would not have had the slightest compunction to do so to kill Fox or one of his tainted sons, the idea of using a witchery to slaughter farm boys and artisans tricked or twisted by sorcery into the Grey Lancer army was so repugnant that she had sent out her order: a witchery could be used to hide, or to escape, or to confuse, or to deceive the enemy. But not to kill or maim.

And they had lost.

“Men are dying today,” Barden said, limping beside her. “Good men who might have lived if those with witcheries had felt free to use them to fight.”

“Va is not in the business of slaughter and warfare.”

“Va is not in the business of making it easy for evil to rule the world!”

Her stomach heaved. Obedience to her orders had led to defeat.

Sweet Va, please tell me I am not wrong. I cannot have been wrong. The thought that her mistake might have killed her men, emptied the city and destroyed the Pontificate – no, it was unthinkable. Va would have told her if there was a better way, surely?

“Am I going too fast for you?” she asked coldly, even though he wasn’t having any difficulty keeping up with her. Given his decrepit body and his advanced age, that didn’t make sense, but she had no energy or will to think about it.

“No,” he said as they descended the winding stair to the lowest level. Around them the stillness of the building was disconcerting; she had grown used to being surrounded by clerics and guards and civil servants and palace staff, all working to keep the Pontificate operating smoothly, but they had all gone now, some to fight, others to seek safety elsewhere.

I will not give up.

They were leaving nothing behind that would be of use to Fox. He might win a battle, but he wouldn’t win the war. How could he?

Va…

But Va was silent, leaving a bitter coldness in her heart.

She wasn’t sure she believed her own words. I don’t know if Va is really with us. So what kind of Pontifect am I? She fingered the acorn and the dried oak leaves in her pocket, and for one precious moment felt a surge of hope, of comfort.

Barden reached the postern door in the outer wall before her. His stride was confident, even though his back was still hunched over his walking stick.

Stride? He doesn’t stride! He hobbles!

“What herbs have you been taking, old friend?” she asked as they waited there for Hawthorn and Vetch with their packs. “You are as frisky as a pup today.” When he didn’t answer, she added, “That’s not your usual walking stick. Where did you get it?”

“I went to the Great Oak to pray yesterday. The shrine tree ate the old one, and gave me this staff in its place.”

She stared in astonishment. “Are you jesting?”

He turned to look at her. “When have you ever known me to jest?”

“But…”

“I leaned my walking stick against the root of the oak. When I finished my prayers the root had grown around it, holding it tight. That’s when the tree offered me a branch to break off.” He held it up. “This. It’s a staff, not a walking stick. With a smooth knob at the top to hold, and a rough heel at the bottom so it won’t slip in the wet. You’re the Pontifect. You explain it.”

She couldn’t think of anything to say.

“I have given the whole of my working life to the Pontificate,” he said slowly, “and my heart has always been Shenat, though no Shenat blood flows there. I longed for a witchery, always knowing I would never have one. I never asked for a reward for my faithfulness, nor expected one, but I was granted it, nonetheless, on my last shrine visit. My back may still be crooked, my hands and knees still knobbled, but for the first time in years, I feel no pain and my tread is sure, my grip is strong.”

She tried to hide her shock. “Did you speak to Shrine Keeper Akorna about this?”

“I did. She said a witchery is to be accepted without reservation.”

“A witchery?”

“Her words.” He raised his gaze to meet hers, and tears welled in his eyes. “In an unexpected form perhaps, but a witchery nonetheless. You are a stubborn woman, Fritillary Reedling. War is indeed an evil thing, but confronted with an even greater evil, you must make judicious use of all your resources. In this, you have made a mistake. You have hobbled your greatest advantage: your shrine keepers and all those with witcheries.”

His words hit her in the gut like a fist, depriving her of words. Her witchery ability to hear honesty and to recognise a lie told her every word he spoke was true, at least to the best of his belief. She felt her life spin out of her control, disintegrating around her.

When Hawthorn and Vetch hurried up with their packs, Barden turned to slip back the three iron bolts on the door and lift the heavy wooden bar. Barden, who ordinarily could not keep up with her normal walking pace, or lift anything heavier than an inkwell or a clutch of papers.

It wasn’t the time to continue the conversation. Instead, she slipped off her Pontifect’s robe and her coif and dropped them on the paving. Underneath she was wearing the clothes of a working townswoman – ankle-length skirt, over-tunic and coat, all slightly grubby and well-worn. She tied a plain square of linen over her head as a scarf, took the key out of the door and nodded to Hawthorn. “Let’s go.”

Outside, the smell of burning was an assault. Hawthorn, who had picked up her robe and coif, shut the door behind them. She locked it and slipped the key into her purse, knowing the gesture was ridiculous; a locked door would stop no one for long. She said to Hawthorn, “This is where we part company, Sergeant.” Her best chance at disappearing was to do so alone, not accompanied by uniformed guards. She gestured at the clothing he held. “I don’t need that any more.”

He halted a salute midway, and nodded instead.

“Go with Va,” she said. “Both of you. Try… try to live to fight another day.”

Barden was already swinging his way down the street supported by his staff, heading for the docks.

When she took one last glance behind as she strode after him, it was to see Vetch donning her robe and coif. She halted and called to him, but he just smiled and hurried away, the robe flapping around his feet.

Dear oak, she didn’t deserve their sacrifice.

Before Va, I will win this fight. I swear it. But the thought echoed in her head like the growl of a toothless dog.

Hurrying after Barden as he disappeared around a corner ahead, she heard nothing to warn her anything was amiss until she turned into the side street that headed towards the riverside docks. She was confronted by the sight of Barden raising his staff in a gesture of defiance before two attackers. A doomed gesture, because the two men he faced were dressed in dirty grey uniforms and armed with lances.

She halted, paralysed, unable to think of how she could help, yet equally unable to flee, deserting him. This was Barden, who had been at her side in all her years as Pontifect, her guide, her mentor, her friend.

The taller of the lancers, a gauntly thin man, poked his lance at Barden almost as if he was bored. “You can kill this one,” he said to his younger, shorter companion.

Barden swung his staff at the stock of the older man’s lance. His clout was weak, ineffectual. The lancer casually moved to deflect the thwack, even as his younger companion moved in to deliver a killing stab with his lance blade.

The staff flew out of Barden’s hand, spinning so fast it was just a blur. It slammed into the younger man’s face with a crack. He dropped where he stood, his lance tumbling from his hand. Half of his face was a bloodied mess of bone and skin, with teeth poking through his cheek. For a moment the older man stood, blinking in surprise, then he raised his lance with an angry cry, jabbing it at Barden with all his body weight behind what should have been a killing blow.

Barden, a frantic look of horror on his face, threw himself backwards to avoid the jab. His staff picked itself up off the cobbles and slammed against the knee of the older lancer to knock him off his feet. He landed with a bone-crunching thud.

Fritillary ran forward to help Barden up. The staff moved – by itself – lifting from the pavement into Barden’s hand. With a look of heartfelt gratitude, he leaned on it. The older lancer, wailing as he clutched his thigh, rocked to and fro, his lower leg at a strange angle. Blood seeped through the cloth of his trousers.

Barden looked down at the staff and ran a loving hand over its smoothed wood. “This,” he said, “is my witchery.” Looking up, he smiled at Fritillary. “I think we are done here. Neither of these fellows will fight again, methinks.”

She took a deep breath, but said nothing. No words would come. Picking up her pack from where she’d dropped it, she followed Barden as he scuttled away from the wounded men like a three-legged spider.

Va help them, she’d been wrong. Horribly, disastrously wrong. Barden’s walking stick, crafted from the wood of the living oak of the hemisphere’s greatest shrine by an unseen guardian, told her that much. The knowledge was an indigestible lump of grief – and hope – in her insides.

As they approached the waiting barge a few minutes later, Barden’s nose wrinkled with distaste. “Curdle me sour, what is it carrying?”

“Salted fish, I believe,” she said. “It seemed an unlikely cargo for a barge bearing the Pontifect.”

He glanced at her, puzzled. “You asked for a barge full of smelly sprats? But aren’t we just crossing the Ard to Staravale?”

“That’s what I wanted everyone to think. In fact, we are going to the last place anyone would think to look for the Pontifect, and the best place to be to get anything done.”

He waited for her to explain, but she didn’t oblige. At this stage, the fewer people who knew, the better. Instead, she said, “We have a war to win.”

“No holds barred?”

She took a deep breath. “No holds barred. Va help us all.”

“Something’s wrong.”

The words, uttered by Saker Rampion, were said softly, but the chill of them iced the back of Ardhi’s neck.

“Something is definitely wrong.”

Ardhi looked upwards. Yes, there was the sea eagle, drifting effortlessly above, scarcely moving a wingtip. It had followed them all the way from Chenderawasi to the coast of Ardrone, often perched on one of the yardarms, sometimes fed fish by the sailors after Saker had assured them it was a bird of good omen.

A bird of the Summer Seas, irrevocably connected now to a man of Ardrone, by Chenderawasi sakti. Va-forsaken magic, these people called it, in their ignorance. Everything the bird saw and felt, Saker saw and felt too, though he often struggled to interpret it.

Even so, when Saker said something was wrong, not one of those standing on the weather deck of Golden Petrel was prepared to ridicule his assertion. His increased perception had proved invaluable on their journey home. He even had the ability to twin himself with the bird, to have his consciousness fly with the eagle and guide it. It meant leaving his body inert and unthinking and vulnerable, not something to be done lightly, especially as there was no guarantee he would or could return to it. Those times were the hardest, and they left Saker exhausted. Bird and man, they’d hated one another in the beginning as they’d fought the link, both wanting to be free and yet both incapable of breaking the tie the sakti had forged.

Ardhi had watched unhappily as the conflict gradually changed from a battle, to acceptance, to respect, but never to affection. It had been difficult for Saker to acknowledge that this wasn’t supposed to be a punishment or a penance, but rather an added weapon in a magical arsenal, all part of the sakti protecting a Summer Seas archipelago from the rapine of invasion.

He looked back at Saker, worry niggling him. The man had paid a high price for that avian connection. The strain was etched into his face, visible in the troubled depths of his gaze as he laboured to maintain his humanity and his sanity. The only time Ardhi saw something of the man Saker had once been was when he played with Piper. Then his sorrow was banished and his eyes would soften with tenderness.

Sighing, he turned his gaze to the shoreline slipping past. Borne on a following breeze, Golden Petrel was making good time towards the royal city of Throssel, already visible in the distance. The larger buildings caught the afternoon sun, walls and towers aglow, glassed windows burnished. The royal standard flew from the palace’s highest point, indicating the king was in residence.

“Over two years,” Lord Juster Dornbeck muttered from where he stood behind the helmsman. “Anything could have happened in that time.” The last news they’d had, in Karradar from a newly arrived Ardronese trader, had been four months old even then. The ship’s merchant-captain had spoken of marauding bands of religious zealots called the Grey Lancers, and an argument between the king and his heir, Prince Ryce, which had left the king well-nigh blind. Pressed for details, the man had been vague. “We’re from Port Sedge down south,” he’d said. “What do we know of snotty nobles and sodding clerics up in Throssel?”

Now, looking at Saker gripping the bulwarks with both hands as if his life depended on his hold, Ardhi wondered if it hadn’t been a mistake to come straight to the Ardronese capital. He couldn’t help but think they should have stopped for news instead of bypassing the port of Hornbeam.

It would have been easy enough. Hornbeam was not far from the estuary’s entrance to the open ocean, and Lord Juster had ordered his prizes, the two Lowmian ships they’d commandeered, to divert there while Golden Petrel sailed on to the royal city. Both of the captured vessels, ravaged by ship’s worm, wallowed like pregnant sows even with the pumps constantly manned. Juster had deemed that the sometimes choppy tidal flows of the Throssel Water might prove the final fatal blow to their seaworthiness and had ordered them in for repairs.

“Saker,” Juster said in answer to his remark about something being amiss, “cryptic utterances about things looking ‘wrong’ are not overly helpful. Could we have a comment, an elucidation of some sort, possibly a scintilla more… specific? You know, like perhaps that fobbing feathered spy of yours can see cannon aimed in our direction?”

“No, it’s not that. It’s the coastline – it’s altered.” Saker had appeared more puzzled than alarmed, but now his bewilderment changed to the shock of realisation. “The oak,” he said. “The King’s Oak. It’s gone.”

The words meant nothing to Ardhi, but all those within earshot on the weather deck blanched.

Juster glowered. “What do you mean? Shrine-oaks don’t disappear!” When a reply was not forthcoming, he snapped out a stream of commands, sending seamen aloft with instructions to report anything out of the ordinary, then ordering the ship’s boy, Banstel, to fetch the telescope from his cabin. “Saker, position that heap of feathers above the palace and tell me what it sees.”

“What do you expect? It doesn’t talk to me, you know. All I get is a picture.”

Juster hesitated, obviously wanting Saker to twin with the bird, but when no offer to do so was forthcoming, he said instead, “A picture which you can interpret.”

Saker sent an eloquent glance Juster’s way, but a moment later the eagle tilted its wings and slid across the sky towards the palace, still several miles ahead of them.

When the telescope was produced, Lord Juster scanned the coastline where the King’s Oak shrine should have been. “That is… uncanny,” he admitted. “I can’t spot the oak, it’s true. But I also can’t discern signs that there’s been a tree cut down. Or burned. It’s just—”

“Not there,” Saker finished. “All I could see was a kind of blur.”

“A local ground mist?”

“No.”

“Rattling pox, a fobbing great tree can’t just vanish.”

“This one has.”

“Could it be the work of A’va?”

“How am I supposed to know?”

“You’re the Shenat witan! You tell me!”

“I would have thought it impossible to wipe a shrine-oak from the surface of the earth, but that’s what it looks like.”

Ardhi edged away into the shadow of the mizzen mast, where he could unsheathe his kris and glance at the blade without them noticing. As always, when his hand closed over the bone of the hilt – Raja Wiramulia’s bone, cleaned and carved by Rani Marsyanda, washed with her tears – he felt the anguish of his memories. And now gold flecks of the Raja’s regalia gleamed fiery red in the blade, always a sign that trouble was close.

“What do you see?” The whisper came from behind him, making him jump. Sorrel, glamoured, had been standing there all along, blended into the mast. In spite of the sakti which allowed him to see through her witchery, he had not noticed her there. Simply dressed in a sailor’s culottes and shirt, she was barefoot because she had been up on the rigging and, like him, preferred the firmer grip of unshod feet. As he watched, she changed the glamour that had blended her into the mast to her own appearance – except this time she clad herself in the illusion of a demure gown.

He smiled, amused at her successful deception travelling the length of the ship aloft without anyone spotting her. “Si-nakal! You imp! You know the captain hates you using your witchery on board.” Juster Dornbeck didn’t particularly like her clad as a sailor either, so it was just as well he’d have no idea that the glamoured dress she was apparently now wearing was all a sham.

“Fig on him! He’s ready enough to make use of it when it suits him. What’s the blade telling you?”

“It’s unhappy,” he said. “Nothing more than that.” They were using the Chenderawasi language, as they often did when alone. She’d asked to learn it and now, speaking with an accent he thought charming, her grasp of the nuances of his island tongue never failed to delight him.

“Not good, then.” She pulled a face.

“No. But did we expect anything different?”

She shook her head. “I’m frightened. I was scared even before I knew a shrine-oak could disappear…” Her gaze remained steady, but her words were poignant in their honesty.

His breath caught in his throat. “All – all we can do is our best.”

“We can’t afford to fail.”

“No. But the Rani implied that our unity – our ternion – is a strength.”

Her hand touched the small pendant at her neck. It was made of stoppered bambu and hung on a gold chain he had bought for her on one of the Spicerie islands. Inside the hollow were three tiny pieces of the old Raja’s tail feathers, each imbued with his Avian sakti. Saker had two more pieces, but no one knew exactly how best to use that magic.

“Piper,” she whispered, and the name summed up all her worries in one word. Her gaze slid away to where the child was playing on the deck with a rope doll made for her by one of the sailors. The dark curls of her hair flopped over her forehead. The prettiest of two-year-olds, she never would keep her bonnet on for more than a few minutes at a time. She looked up just then, saw Sorrel and waved the doll in her direction. “Look, Mama!”

Sorrel waved back.

If they failed… If they didn’t use the sakti wisely…

He swallowed hard at the thought of what would happen. If the Chenderawasi circlet Piper wore around her neck failed to control the sorcerous blood she had inherited, she could follow in the footsteps of her father, Valerian Fox. Possibly even worse was the knowledge that – if they failed to contain the rampant greed of the Va-cherished Hemisphere – then the islands of the Summer Seas, his own included, would be devastated by the guns of Lowmian and Ardronese merchants. His people would lose their freedom.

“Our failures are all in the past,” he said, striving to sound confident. “Yours, mine, Saker’s – they were monumental, they delivered their lessons, but they are in the past. Now we are three, a ternion, uni

A cerulean sky was almost cloudless. Spiralling up into the blue, a songbird poured a joyous melody into the spring air to entice his mate and threaten his rivals.

A perfect day, a day to feel good about being alive.

Except it held no promise that any of them would live long enough to see another sunrise.

A puff of smoke rose above the distant buildings, silent and silky white, followed a moment later by an explosion that overwhelmed the birdsong and tore the air apart. The foundations below their feet quivered. A distant cloud of dust and debris lifted into the air, blossomed outwards with the beauty of an unfolding flower, then rained down on the city with an ugly roar. Fritillary winced and looked away.

“Cannon,” Vetch said unnecessarily.

“It was only a matter of time,” said Hawthorn. “The sole unanswered question is where they got them.” Cannon were rare in the Va-cherished lands.

“Raided the gun decks of one of the king’s galleons?” Vetch suggested.

“Imported by mastodon across the ice from Pashalin, more likely,” Fritillary said. “With the gunpowder to fire them.”

“Va-less curs.” Another unnecessary mutter from Vetch.

Silence returned.

Below, the streets were eerily empty, the houses shuttered, the chimneys cold, the doors closed. The only living thing within her sight was a cat, which a moment ago had been sunning itself on a doorstep with undisturbed aplomb. Now it was scrabbling up a wall in fright. In the distance to the north, another rumble of cannon fire was followed by a brief silence as the world held its breath, then a second jarring, heart-wrenching impact that shattered her soul.

Her city. Her failure.

She had long since given the order for civilians to evacuate, to flee across the river to Staravale, leaving only those prepared to fight alongside the city guard and the soldiers of the Pontificate. Her soldiers.

In truth, she had asked them to die so that others could escape. So far, they had held the walls, but that wouldn’t last.

Another cannonball shot, another hit, another puff of dust and smoke, more birds rising with startled cries into the sky. By the sound of it, the besiegers only had several light cannon, but pound away at the northern gate for long enough, and it would eventually splinter. Lob explosive-filled balls over the wall and defenders would die.

We’ve lost.

So where are you, Va? Are we the Forsaken Lands now? She sighed. There she was, blaming Va. How ridiculous was that?

The minutes dragged by. More cannon fire, more sounds of a city falling, brick by brick, tile by tile. Man by man.

“Your Reverence, it’s time.” Hawthorn, nagging as usual. Unable to fight because of his failing eyesight, but still desperate to protect her.

“Not yet.”

“He’s right,” Barden said.

“Soon.” She couldn’t leave, not until she was sure all was lost. My city. My resplendent city.

In the street below, a horse swung into the main palace thoroughfare bearing a man in the uniform of her palace guard. They all watched in silence as he rode at a gallop into the forecourt through the open gate, halted his mount at the foot of the stairs to the terrace, then flung himself off to take the steps three at a time. A makeshift bandage on one of his arms partially covered a tattered sleeve drenched in blood.

He was young. Seventeen? Eighteen? Too young to have endured all he must have seen and done that day.

“Reporting from Captain Marsh,” he said when he reached them, the words pitched too high, just short of panic.

“What’s the latest?” She tried to sound calm, but rage and fear had tightened her throat until it ached.

His voice wavered as he answered. “The wall is breached to the north. The men are still fighting, street by street, but – it’s just a matter of time.”

“I can smell the burning.” Wood, and worse. They could see it now, too; a plume of smoke carrying showers of sparks upwards. Why would they burn the city? Didn’t he want to rule it, that sorcerous horror Fox? Valerian Fox. What good was a city to him if it was burned to the ground? “The shrine?” she asked. The lad would have passed it on his way to the palace. The city of Vavala had been built to encompass a spring that fed the River Ard and the Great Oak that grew there, the oldest and most sacred place in the whole Va-cherished Hemisphere, where the Way of the Flow and the Way of the Oak combined.

“Gone,” he whispered. He was choking, forcing the words out as he struggled to control his emotion. “There’s no sign of the oak.”

She nodded. It was the answer she’d expected. “Have faith. It will return when times are safe.” She patted his arm, despising herself for the futile pretension of both words and action, but she didn’t know what else to do. How could you comfort someone who had indeed put their faith in Va, and in their Pontifect, only to be let down so badly?

He looked at her, appalled, and she was pierced to the bone by his horror. He could not conceive of a world where the oak was not a constant, a place to turn to in troubled times.

By earth and oak, what have you done to him and others like him, Fritillary?

“The evacuation?” she asked, and wondered at the blandness of her tone.

“Th – those who wanted to leave have gone. The captain says you must go now. He doesn’t know how much longer he can hold against the Grey Lancers. The smutch—” He choked back a sob. “It makes men despair when they should be fighting. I saw—” He swallowed. “I saw grown men drop their swords and sink to their knees, weeping.”

“You’ve felt the smutch?”

“We all have.” He wiped tears from his begrimed face. “If Your Reverence had not sent the oak leaves, we would all have succumbed.”

She had ordered every guard to place a leaf against his chest; she’d had sacred acorns distributed, hoping that would grant them courage, but, dear Va, Prime Valerian Fox was at the gates and he had grown in power. She shuddered to think how. Lord Herelt Deremer of the Dire Sweepers had told her that Valerian gained his greatest strength by draining his own ill-begotten sons. Possibly Herelt was right. She’d certainly believed him earlier, when he’d told her Fox sucked the life from children in order to add to his own life force, leaving them to sicken and die of the Horned Plague.

She took a deep breath. “Tell the captain I am leaving now. Tell him there are no further orders; he is to do what he thinks is best. Tell him Va is with us all in the end, and every man who fights here today will be remembered for all time.”

But, oh, Va! Why have you not shown us how to combat this evil? What have we done that we are left so helpless?

Deceived by words, confused by the power of coercion and enticement that Prime Fox’s numerous sons possessed, men and boys had flocked to the Prime’s banner, like hens after a strutting rooster. Ordinary men made into willing, mindless automatons by sorcery. Even unseen guardians and shrine keepers, who were able to resist the coercion themselves, had been unable to combat the spreading evil. She had drained the coffers of the Pontificate in an effort to recruit and train the faithful, but there was only so much an ordinary man or woman could do when faced with sorcery. In desperation, she had swallowed her revulsion of all Lord Herelt Deremer stood for, and allied herself to him – but most of his resources and his men were in Lowmeer, not in the Principalities or the kingdom of Ardrone.

When the young guardsman had gone, she could not rid herself of the notion that she had sent him to his death. Bitterly, she accepted the truth of that thought, and turned to Hawthorn. “Sergeant, you and Vetch bring our packs to the postern door. Barden and I will meet you both there.”

As she and her secretary headed through the palace halls, their footsteps and the tap of his wooden staff echoing in the emptiness, she muttered, “I was not born for this. I am no warrior.”

“No one is born for war.”

For once, he was moving fast alongside her, even with his bent back. His liver-spotted hand clasped the head of his walking stick, using it with a driving purpose. She blinked, surprised at his turn of speed.

“All it would have taken was a word from you,” he said, and she heard condemnation in his tone. “You could have ordered those clerics blessed with witcheries to use them—”

“They would have lost their witcheries. Or died! Not now, Barden, not now.” They’d had this argument a hundred times over the past year. Was it moral to use a Va-given witchery to kill? All she’d been taught, all she’d believed in, had told her witcheries were to be used for good, that to use one to kill was not only wrong, but would result in the loss of the perpetrator’s witchery. While she would not have had the slightest compunction to do so to kill Fox or one of his tainted sons, the idea of using a witchery to slaughter farm boys and artisans tricked or twisted by sorcery into the Grey Lancer army was so repugnant that she had sent out her order: a witchery could be used to hide, or to escape, or to confuse, or to deceive the enemy. But not to kill or maim.

And they had lost.

“Men are dying today,” Barden said, limping beside her. “Good men who might have lived if those with witcheries had felt free to use them to fight.”

“Va is not in the business of slaughter and warfare.”

“Va is not in the business of making it easy for evil to rule the world!”

Her stomach heaved. Obedience to her orders had led to defeat.

Sweet Va, please tell me I am not wrong. I cannot have been wrong. The thought that her mistake might have killed her men, emptied the city and destroyed the Pontificate – no, it was unthinkable. Va would have told her if there was a better way, surely?

“Am I going too fast for you?” she asked coldly, even though he wasn’t having any difficulty keeping up with her. Given his decrepit body and his advanced age, that didn’t make sense, but she had no energy or will to think about it.

“No,” he said as they descended the winding stair to the lowest level. Around them the stillness of the building was disconcerting; she had grown used to being surrounded by clerics and guards and civil servants and palace staff, all working to keep the Pontificate operating smoothly, but they had all gone now, some to fight, others to seek safety elsewhere.

I will not give up.

They were leaving nothing behind that would be of use to Fox. He might win a battle, but he wouldn’t win the war. How could he?

Va…

But Va was silent, leaving a bitter coldness in her heart.

She wasn’t sure she believed her own words. I don’t know if Va is really with us. So what kind of Pontifect am I? She fingered the acorn and the dried oak leaves in her pocket, and for one precious moment felt a surge of hope, of comfort.

Barden reached the postern door in the outer wall before her. His stride was confident, even though his back was still hunched over his walking stick.

Stride? He doesn’t stride! He hobbles!

“What herbs have you been taking, old friend?” she asked as they waited there for Hawthorn and Vetch with their packs. “You are as frisky as a pup today.” When he didn’t answer, she added, “That’s not your usual walking stick. Where did you get it?”

“I went to the Great Oak to pray yesterday. The shrine tree ate the old one, and gave me this staff in its place.”

She stared in astonishment. “Are you jesting?”

He turned to look at her. “When have you ever known me to jest?”

“But…”

“I leaned my walking stick against the root of the oak. When I finished my prayers the root had grown around it, holding it tight. That’s when the tree offered me a branch to break off.” He held it up. “This. It’s a staff, not a walking stick. With a smooth knob at the top to hold, and a rough heel at the bottom so it won’t slip in the wet. You’re the Pontifect. You explain it.”

She couldn’t think of anything to say.

“I have given the whole of my working life to the Pontificate,” he said slowly, “and my heart has always been Shenat, though no Shenat blood flows there. I longed for a witchery, always knowing I would never have one. I never asked for a reward for my faithfulness, nor expected one, but I was granted it, nonetheless, on my last shrine visit. My back may still be crooked, my hands and knees still knobbled, but for the first time in years, I feel no pain and my tread is sure, my grip is strong.”

She tried to hide her shock. “Did you speak to Shrine Keeper Akorna about this?”

“I did. She said a witchery is to be accepted without reservation.”

“A witchery?”

“Her words.” He raised his gaze to meet hers, and tears welled in his eyes. “In an unexpected form perhaps, but a witchery nonetheless. You are a stubborn woman, Fritillary Reedling. War is indeed an evil thing, but confronted with an even greater evil, you must make judicious use of all your resources. In this, you have made a mistake. You have hobbled your greatest advantage: your shrine keepers and all those with witcheries.”

His words hit her in the gut like a fist, depriving her of words. Her witchery ability to hear honesty and to recognise a lie told her every word he spoke was true, at least to the best of his belief. She felt her life spin out of her control, disintegrating around her.

When Hawthorn and Vetch hurried up with their packs, Barden turned to slip back the three iron bolts on the door and lift the heavy wooden bar. Barden, who ordinarily could not keep up with her normal walking pace, or lift anything heavier than an inkwell or a clutch of papers.

It wasn’t the time to continue the conversation. Instead, she slipped off her Pontifect’s robe and her coif and dropped them on the paving. Underneath she was wearing the clothes of a working townswoman – ankle-length skirt, over-tunic and coat, all slightly grubby and well-worn. She tied a plain square of linen over her head as a scarf, took the key out of the door and nodded to Hawthorn. “Let’s go.”

Outside, the smell of burning was an assault. Hawthorn, who had picked up her robe and coif, shut the door behind them. She locked it and slipped the key into her purse, knowing the gesture was ridiculous; a locked door would stop no one for long. She said to Hawthorn, “This is where we part company, Sergeant.” Her best chance at disappearing was to do so alone, not accompanied by uniformed guards. She gestured at the clothing he held. “I don’t need that any more.”

He halted a salute midway, and nodded instead.

“Go with Va,” she said. “Both of you. Try… try to live to fight another day.”

Barden was already swinging his way down the street supported by his staff, heading for the docks.

When she took one last glance behind as she strode after him, it was to see Vetch donning her robe and coif. She halted and called to him, but he just smiled and hurried away, the robe flapping around his feet.

Dear oak, she didn’t deserve their sacrifice.

Before Va, I will win this fight. I swear it. But the thought echoed in her head like the growl of a toothless dog.

Hurrying after Barden as he disappeared around a corner ahead, she heard nothing to warn her anything was amiss until she turned into the side street that headed towards the riverside docks. She was confronted by the sight of Barden raising his staff in a gesture of defiance before two attackers. A doomed gesture, because the two men he faced were dressed in dirty grey uniforms and armed with lances.

She halted, paralysed, unable to think of how she could help, yet equally unable to flee, deserting him. This was Barden, who had been at her side in all her years as Pontifect, her guide, her mentor, her friend.

The taller of the lancers, a gauntly thin man, poked his lance at Barden almost as if he was bored. “You can kill this one,” he said to his younger, shorter companion.

Barden swung his staff at the stock of the older man’s lance. His clout was weak, ineffectual. The lancer casually moved to deflect the thwack, even as his younger companion moved in to deliver a killing stab with his lance blade.

The staff flew out of Barden’s hand, spinning so fast it was just a blur. It slammed into the younger man’s face with a crack. He dropped where he stood, his lance tumbling from his hand. Half of his face was a bloodied mess of bone and skin, with teeth poking through his cheek. For a moment the older man stood, blinking in surprise, then he raised his lance with an angry cry, jabbing it at Barden with all his body weight behind what should have been a killing blow.

Barden, a frantic look of horror on his face, threw himself backwards to avoid the jab. His staff picked itself up off the cobbles and slammed against the knee of the older lancer to knock him off his feet. He landed with a bone-crunching thud.

Fritillary ran forward to help Barden up. The staff moved – by itself – lifting from the pavement into Barden’s hand. With a look of heartfelt gratitude, he leaned on it. The older lancer, wailing as he clutched his thigh, rocked to and fro, his lower leg at a strange angle. Blood seeped through the cloth of his trousers.

Barden looked down at the staff and ran a loving hand over its smoothed wood. “This,” he said, “is my witchery.” Looking up, he smiled at Fritillary. “I think we are done here. Neither of these fellows will fight again, methinks.”

She took a deep breath, but said nothing. No words would come. Picking up her pack from where she’d dropped it, she followed Barden as he scuttled away from the wounded men like a three-legged spider.

Va help them, she’d been wrong. Horribly, disastrously wrong. Barden’s walking stick, crafted from the wood of the living oak of the hemisphere’s greatest shrine by an unseen guardian, told her that much. The knowledge was an indigestible lump of grief – and hope – in her insides.

As they approached the waiting barge a few minutes later, Barden’s nose wrinkled with distaste. “Curdle me sour, what is it carrying?”

“Salted fish, I believe,” she said. “It seemed an unlikely cargo for a barge bearing the Pontifect.”

He glanced at her, puzzled. “You asked for a barge full of smelly sprats? But aren’t we just crossing the Ard to Staravale?”

“That’s what I wanted everyone to think. In fact, we are going to the last place anyone would think to look for the Pontifect, and the best place to be to get anything done.”

He waited for her to explain, but she didn’t oblige. At this stage, the fewer people who knew, the better. Instead, she said, “We have a war to win.”

“No holds barred?”

She took a deep breath. “No holds barred. Va help us all.”

“Something’s wrong.”

The words, uttered by Saker Rampion, were said softly, but the chill of them iced the back of Ardhi’s neck.

“Something is definitely wrong.”

Ardhi looked upwards. Yes, there was the sea eagle, drifting effortlessly above, scarcely moving a wingtip. It had followed them all the way from Chenderawasi to the coast of Ardrone, often perched on one of the yardarms, sometimes fed fish by the sailors after Saker had assured them it was a bird of good omen.

A bird of the Summer Seas, irrevocably connected now to a man of Ardrone, by Chenderawasi sakti. Va-forsaken magic, these people called it, in their ignorance. Everything the bird saw and felt, Saker saw and felt too, though he often struggled to interpret it.

Even so, when Saker said something was wrong, not one of those standing on the weather deck of Golden Petrel was prepared to ridicule his assertion. His increased perception had proved invaluable on their journey home. He even had the ability to twin himself with the bird, to have his consciousness fly with the eagle and guide it. It meant leaving his body inert and unthinking and vulnerable, not something to be done lightly, especially as there was no guarantee he would or could return to it. Those times were the hardest, and they left Saker exhausted. Bird and man, they’d hated one another in the beginning as they’d fought the link, both wanting to be free and yet both incapable of breaking the tie the sakti had forged.

Ardhi had watched unhappily as the conflict gradually changed from a battle, to acceptance, to respect, but never to affection. It had been difficult for Saker to acknowledge that this wasn’t supposed to be a punishment or a penance, but rather an added weapon in a magical arsenal, all part of the sakti protecting a Summer Seas archipelago from the rapine of invasion.

He looked back at Saker, worry niggling him. The man had paid a high price for that avian connection. The strain was etched into his face, visible in the troubled depths of his gaze as he laboured to maintain his humanity and his sanity. The only time Ardhi saw something of the man Saker had once been was when he played with Piper. Then his sorrow was banished and his eyes would soften with tenderness.

Sighing, he turned his gaze to the shoreline slipping past. Borne on a following breeze, Golden Petrel was making good time towards the royal city of Throssel, already visible in the distance. The larger buildings caught the afternoon sun, walls and towers aglow, glassed windows burnished. The royal standard flew from the palace’s highest point, indicating the king was in residence.

“Over two years,” Lord Juster Dornbeck muttered from where he stood behind the helmsman. “Anything could have happened in that time.” The last news they’d had, in Karradar from a newly arrived Ardronese trader, had been four months old even then. The ship’s merchant-captain had spoken of marauding bands of religious zealots called the Grey Lancers, and an argument between the king and his heir, Prince Ryce, which had left the king well-nigh blind. Pressed for details, the man had been vague. “We’re from Port Sedge down south,” he’d said. “What do we know of snotty nobles and sodding clerics up in Throssel?”

Now, looking at Saker gripping the bulwarks with both hands as if his life depended on his hold, Ardhi wondered if it hadn’t been a mistake to come straight to the Ardronese capital. He couldn’t help but think they should have stopped for news instead of bypassing the port of Hornbeam.

It would have been easy enough. Hornbeam was not far from the estuary’s entrance to the open ocean, and Lord Juster had ordered his prizes, the two Lowmian ships they’d commandeered, to divert there while Golden Petrel sailed on to the royal city. Both of the captured vessels, ravaged by ship’s worm, wallowed like pregnant sows even with the pumps constantly manned. Juster had deemed that the sometimes choppy tidal flows of the Throssel Water might prove the final fatal blow to their seaworthiness and had ordered them in for repairs.

“Saker,” Juster said in answer to his remark about something being amiss, “cryptic utterances about things looking ‘wrong’ are not overly helpful. Could we have a comment, an elucidation of some sort, possibly a scintilla more… specific? You know, like perhaps that fobbing feathered spy of yours can see cannon aimed in our direction?”

“No, it’s not that. It’s the coastline – it’s altered.” Saker had appeared more puzzled than alarmed, but now his bewilderment changed to the shock of realisation. “The oak,” he said. “The King’s Oak. It’s gone.”

The words meant nothing to Ardhi, but all those within earshot on the weather deck blanched.

Juster glowered. “What do you mean? Shrine-oaks don’t disappear!” When a reply was not forthcoming, he snapped out a stream of commands, sending seamen aloft with instructions to report anything out of the ordinary, then ordering the ship’s boy, Banstel, to fetch the telescope from his cabin. “Saker, position that heap of feathers above the palace and tell me what it sees.”

“What do you expect? It doesn’t talk to me, you know. All I get is a picture.”

Juster hesitated, obviously wanting Saker to twin with the bird, but when no offer to do so was forthcoming, he said instead, “A picture which you can interpret.”

Saker sent an eloquent glance Juster’s way, but a moment later the eagle tilted its wings and slid across the sky towards the palace, still several miles ahead of them.

When the telescope was produced, Lord Juster scanned the coastline where the King’s Oak shrine should have been. “That is… uncanny,” he admitted. “I can’t spot the oak, it’s true. But I also can’t discern signs that there’s been a tree cut down. Or burned. It’s just—”

“Not there,” Saker finished. “All I could see was a kind of blur.”

“A local ground mist?”

“No.”

“Rattling pox, a fobbing great tree can’t just vanish.”

“This one has.”

“Could it be the work of A’va?”

“How am I supposed to know?”

“You’re the Shenat witan! You tell me!”

“I would have thought it impossible to wipe a shrine-oak from the surface of the earth, but that’s what it looks like.”

Ardhi edged away into the shadow of the mizzen mast, where he could unsheathe his kris and glance at the blade without them noticing. As always, when his hand closed over the bone of the hilt – Raja Wiramulia’s bone, cleaned and carved by Rani Marsyanda, washed with her tears – he felt the anguish of his memories. And now gold flecks of the Raja’s regalia gleamed fiery red in the blade, always a sign that trouble was close.

“What do you see?” The whisper came from behind him, making him jump. Sorrel, glamoured, had been standing there all along, blended into the mast. In spite of the sakti which allowed him to see through her witchery, he had not noticed her there. Simply dressed in a sailor’s culottes and shirt, she was barefoot because she had been up on the rigging and, like him, preferred the firmer grip of unshod feet. As he watched, she changed the glamour that had blended her into the mast to her own appearance – except this time she clad herself in the illusion of a demure gown.

He smiled, amused at her successful deception travelling the length of the ship aloft without anyone spotting her. “Si-nakal! You imp! You know the captain hates you using your witchery on board.” Juster Dornbeck didn’t particularly like her clad as a sailor either, so it was just as well he’d have no idea that the glamoured dress she was apparently now wearing was all a sham.

“Fig on him! He’s ready enough to make use of it when it suits him. What’s the blade telling you?”

“It’s unhappy,” he said. “Nothing more than that.” They were using the Chenderawasi language, as they often did when alone. She’d asked to learn it and now, speaking with an accent he thought charming, her grasp of the nuances of his island tongue never failed to delight him.

“Not good, then.” She pulled a face.

“No. But did we expect anything different?”

She shook her head. “I’m frightened. I was scared even before I knew a shrine-oak could disappear…” Her gaze remained steady, but her words were poignant in their honesty.

His breath caught in his throat. “All – all we can do is our best.”

“We can’t afford to fail.”

“No. But the Rani implied that our unity – our ternion – is a strength.”

Her hand touched the small pendant at her neck. It was made of stoppered bambu and hung on a gold chain he had bought for her on one of the Spicerie islands. Inside the hollow were three tiny pieces of the old Raja’s tail feathers, each imbued with his Avian sakti. Saker had two more pieces, but no one knew exactly how best to use that magic.

“Piper,” she whispered, and the name summed up all her worries in one word. Her gaze slid away to where the child was playing on the deck with a rope doll made for her by one of the sailors. The dark curls of her hair flopped over her forehead. The prettiest of two-year-olds, she never would keep her bonnet on for more than a few minutes at a time. She looked up just then, saw Sorrel and waved the doll in her direction. “Look, Mama!”

Sorrel waved back.

If they failed… If they didn’t use the sakti wisely…

He swallowed hard at the thought of what would happen. If the Chenderawasi circlet Piper wore around her neck failed to control the sorcerous blood she had inherited, she could follow in the footsteps of her father, Valerian Fox. Possibly even worse was the knowledge that – if they failed to contain the rampant greed of the Va-cherished Hemisphere – then the islands of the Summer Seas, his own included, would be devastated by the guns of Lowmian and Ardronese merchants. His people would lose their freedom.

“Our failures are all in the past,” he said, striving to sound confident. “Yours, mine, Saker’s – they were monumental, they delivered their lessons, but they are in the past. Now we are three, a ternion, uni

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

The Fall of the Dagger

Glenda Larke

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved