- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

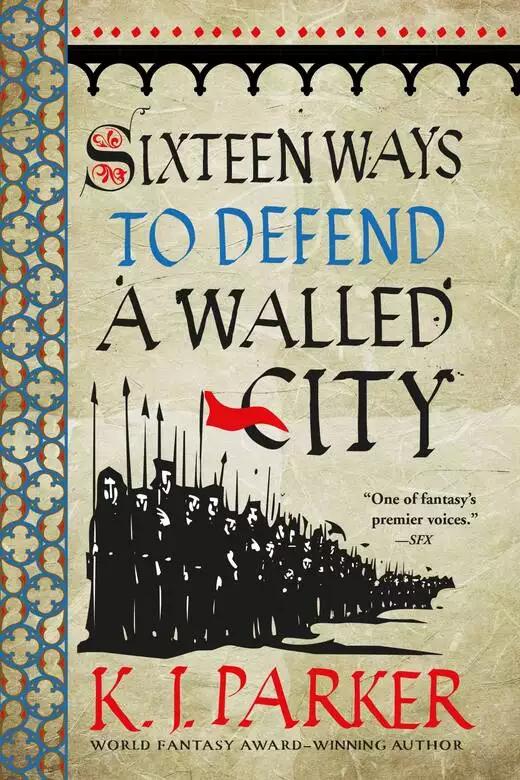

K. J. Parker's new novel is the remarkable tale of the siege of a walled city and the even more remarkable man who had to defend it.

A siege is approaching, and the city has little time to prepare. The people have no food and no weapons, and the enemy has sworn to slaughter them all.

To save the city will take a miracle, but what it has is Orhan. A colonel of engineers, Orhan has far more experience with bridge building than battles, is a cheat and a liar, and has a serious problem with authority. He is, in other words, perfect for the job.

Sixteen Ways to Defend a Walled City is the story of Orhan, son of Siyyah Doctus Felix Praeclarissimus, and his history of the Great Siege, written down so that the deeds and sufferings of great men may never be forgotten.

Release date: April 9, 2019

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Sixteen Ways to Defend a Walled City

K.J. Parker

I took the overland route from Traiecta to Cirte, across one of my bridges (a rush job I did fifteen years ago, only meant to last a month, still there and still the only way across the Lusen unless you go twenty-six miles out of your way to Pons Jovianis) then down through the pass onto the coastal plain. Fabulous view as you come through the pass, that huge flat green patchwork with the blue of the Bay beyond, and Classis as a geometrically perfect star, three arms on land, three jabbing out into the sea. Analyse the design and it becomes clear that it’s purely practical and utilitarian, straight out of the field operations manual. Furthermore, as soon as you drop down onto the plain you can’t see the shape, unless you happen to be God. The three seaward arms are tapered jetties, while their landward counterparts are defensive bastions, intended to cover the three main gates with enfilading fire on two sides. Even further more, when Classis was built ninety years ago, there was a dirty great forest in the way (felled for charcoal during the Social War, all stumps, marsh and bramble-fuzz now), so you wouldn’t have been able to see it from the pass, and that strikingly beautiful statement of Imperial power must therefore be mere chance and serendipity. By the time I reached the way station at Milestone 2776 I couldn’t see Classis at all, though of course it was dead easy to find. Just follow the arrow-straight military road on its six-foot embankment, and, next thing you know, you’re there.

Please note I didn’t come in on the military mail. As Colonel-in-Chief of the Engineers, I’m entitled; but, as a milkface (not supposed to call us that, everybody does, doesn’t bother me, I like milk) it’s accepted that I don’t, because of the distress I might cause to Imperials finding themselves banged up in a coach with me for sixteen hours a day. Not that they’d say anything, of course. The Robur pride themselves on their good manners, and, besides, calling a milkface a milkface is Conduct Prejudicial and can get you court-martialled. For the record, nobody’s ever faced charges on that score, which proves (doesn’t it) that Imperials aren’t biased or bigoted in any way. On the other hand, several dozen auxiliary officers have been tried and cashiered for calling an Imperial a blueskin, so you can see just how wicked and deserving of contempt my lot truly are.

No, I made the whole four-day trip on a civilian carrier’s cart. The military mail, running non-stop and changing horses at way stations every twenty miles, takes five days and a bit, but my cart was carrying fish; marvellous incentive to get a move on.

The cart rumbled up to the middle gate and I hopped off and hobbled up to the sentry, who scowled at me, then saw the scrambled egg on my collar. For a split second I thought he was going to arrest me for impersonating an officer (wouldn’t be the first time). I walked past him, then jumped sideways to avoid being run down by a cart the size of a cathedral. That’s Classis.

My pal the clerk’s office was in Block 374, Row 42, Street 7. They’ve heard of sequential numbering in Supply but clearly aren’t convinced that it’d work, so Block 374 is wedged in between Blocks 217 and 434. Street 7 leads from Street 4 into Street 32. But it must be all right, because I can find my way about there, and I’m just a bridge builder, nobody.

He wasn’t there. Sitting at his desk was a six-foot-six Robur in a milk-white monk’s habit. He was bald as an egg, and he looked at me as though I was something the dog had brought in. I mentioned my pal’s name. He smiled.

“Reassigned,” he said.

Oh. “He never mentioned it.”

“It wasn’t the sort of reassignment you’d want to talk about.” He looked me up and down; I half expected him to roll back my upper lip so he could inspect my teeth. “Can I help you?”

I gave him the big smile. “I need rope.”

“Sorry.” He looked so happy. “No rope.”

“I have a sealed requisition.”

He held out his hand. I showed him my piece of paper. I’m pretty sure he spotted the seal was a fake. “Unfortunately, we have no rope at present,” he said. “As soon as we get some—”

I nodded. I didn’t go to staff college so I know squat about strategy and tactics, but I know when I’ve lost and it’s time to withdraw in good order. “Thank you,” I said. “Sorry to have bothered you.”

“No bother.” His smile said he hadn’t finished with me yet. “You can leave that with me.”

I was still holding the phony requisition with the highly illegal seal. “Thanks,” I said, “but shouldn’t I resubmit it through channels? I wouldn’t want you thinking I was trying to jump the queue.”

“Oh, I think we can bend the rules once in a while.” He held out his hand again. Damn, I thought. And then the enemy saved me.

(Which is the story of my life, curiously enough. I’ve had an amazing number of lucky breaks in my life, far more than my fair share, which is why, when I got the citizenship, I chose Felix as my proper name. Good fortune has smiled on me at practically every crucial turning point in my remarkable career. But the crazy thing is, the agency of my good fortune has always—invariably—been the enemy. Thus: when I was seven years old, the Hus attacked our village, slaughtered my parents, dragged me away by the hair and sold me to a Sherden; who taught me the carpenter’s trade—thereby trebling my value—and sold me on to a shipyard. Three years after that, when I was nineteen, the Imperial army mounted a punitive expedition against the Sherden pirates; guess who was among the prisoners carted back to the empire. The Imperial navy is always desperately short of skilled shipwrights. They let me join up, which meant citizenship, and I was a foreman at age twenty-two. Then the Echmen invaded, captured the city where I was stationed; I was one of the survivors and transferred to the Engineers, of whom I now have the honour to be Colonel-in-Chief. I consider my point made. My meteoric rise, from illiterate barbarian serf to commander of an Imperial regiment, is due to the Hus, the Sherden, the Echmen and, last but not least, the Robur, who are proud of the fact that over the last hundred years they’ve slaughtered in excess of a million of my people. One of those here-today-gone-tomorrow freak cults you get in the City says that the way to virtue is loving your enemies. I have no problem with that. My enemies have always come through for me, and I owe them everything. My friends, on the other hand, have caused me nothing but aggravation and pain. Just as well I’ve had so very few of them.)

I noticed I no longer had his full attention. He was peering through his little window. After a moment, I shuffled closer and looked over his shoulder.

“Is that smoke?” I said.

He wasn’t looking at me. “Yes.”

Fire, in a place like Classis, is bad news. Curious how people react. He seemed frozen stiff. I felt jumpy as a cat. I elbowed myself a better view, as the long shed that had been leaking smoke from two windows suddenly went up in flames like a torch.

“What do you keep in there?” I asked.

“Rope,” he said. “Three thousand miles of it.”

I left him gawping and ran. Milspec rope is heavily tarred, and all the sheds at Classis are thatched. Time to be somewhere else.

I dashed out into the yard. There were people running in every direction. Some of them didn’t look like soldiers, or clerks. One of them raced toward me, then stopped.

“Excuse me,” I said. “Do you know—?”

He stabbed me. I hadn’t seen the sword in his hand. I thought; what the devil are you playing at? He pulled the sword out and swung it at my head. I may not be the most perceptive man you’ll ever meet, but I can read between the lines; he didn’t like me. I sidestepped, tripped his heels and kicked his face in. That’s not in the drill manuals, but you pick up a sort of alternative education when you’re brought up by slavers—

Sequence of thoughts; I guess the tripping and kicking thing reminded me of the Sherden who taught it to me (by example), and that made me think of pirates, and then I understood. I trod on his ear for luck till something cracked—not that I hold grudges—and looked round for somewhere to hide.

Really bad things happening all around you take time to sink in. Sherden pirates running amok in Classis? Couldn’t be happening. So I found a shady doorway, held perfectly still and used my eyes. Yes, in fact, it was happening, and to judge from the small slice of the action I could see, they were having things very much their own way. The Imperial army didn’t seem to be troubling them at all; they were preoccupied with fighting the fire in the rope shed, and the Sherden cut them down and shot them as they dashed about with buckets and ladders and long hooks, and nobody seemed to realise what was going on except me, and I don’t count. Pretty soon there were no Imperials left in the yard, and the Sherden were backing up carts to the big sheds and pitching stuff in. Never any shortage of carts at Classis. They were hard workers, I’ll give them that. Try and get a gang of dockers or warehousemen to load two hundred size-four carts in forty minutes. I guess that’s the difference between hired men and self-employed.

I imagine the fire was an accident, because it rather spoiled things for the Sherden. It spread from one shed to a load of others before they had a chance to loot them, then burned up the main stable block and coach-houses, where most of the carts would have been, before the wind changed direction and sent it roaring through the barracks and the secondary admin blocks. That meant it was coming straight at me. By now, there were no soldiers or clerks to be seen, only the bad guys, and I’d stick out like a sore thumb in my regulation cloak and tunic. So I took off the cloak, noticed a big red stain down my front—oh yes, I’d been stabbed, worry about that later—pulled off the dead pirate’s smock and dragged it over my head. Then I pranced away across the yard, looking like I had a job to do.

I got about thirty yards and fell over. I was mildly surprised, then realised: not just a flesh wound. I felt ridiculously weak and terribly sleepy. Then someone was standing over me, a Sherden, with a spear in his hand. Hell, I thought, and then: not that it matters.

“Are you all right?” he said.

Me and good fortune. How lucky I was to have been born a milkface. “I’m fine,” I said. “Really.”

He grinned. “Bullshit,” he said, and hauled me to my feet. I saw him notice my boots—issue beetlecrushers, you can’t buy them in stores. Then I saw he was wearing them, too. Pirates. Dead men’s shoes. “Come on,” he said. “Lean on me, you’ll be fine.”

He put my arm round his neck, then grabbed me round the waist and walked me across to the nearest cart. The driver helped him haul me up, and they laid me down gently on a huge stack of rolled-up lamellar breastplates. My rescuer took off his smock, rolled it up and put it under my head. “Get him back to the ship, they’ll see to him there,” he said, and that was the last I saw of him.

Simple as that. The way the looters were going about their business, quickly and efficiently, it was pretty obvious that there were no Imperial personnel left for them to worry about—apart from me, lovingly whisked away from danger by my enemies. The cart rumbled through the camp to the middle jetty. There were a dozen ships tied up on either side. The driver wasn’t looking, so I was able to scramble off the cart and bury myself in a big coil of rope, where I stayed until the last ship set sail.

Some time later, a navy cutter showed up. Just in time, I remembered to struggle out of the Sherden smock that had saved my life. It’d have been the death of me if I’d been caught wearing it by our lot.

Which is the reason—one of the reasons—why I’ve decided to write this history. Under normal circumstances I wouldn’t have bothered, wouldn’t have presumed—who am I, to take upon myself the recording of the deeds and sufferings of great men, and so on. But I was there; not just all through the siege, but right at the very beginning. As I may already have mentioned, I’ve had far more good luck in my life than I could possibly have deserved, and when—time after time after time—some unseen hand scoops you up from under the wheels, so to speak, and puts you safely down on the roadside, you have to start wondering, why? And the only capacity in which I figure I’m fit to serve is that of witness. After all, anyone can testify in an Imperial court of law; even children, women, slaves, milkfaces, though of course it’s up to the judge to decide what weight to give to the evidence of the likes of me. So; if luck figures I’m good enough to command the Engineers, maybe she reckons I can be a historian, too. Think of that. Immortality. A turf-cutter’s son from north of the Bull’s Neck living for ever on the spine of a book. Wouldn’t that be something.

I wasn’t the only survivor. A deputy quartermaster’s clerk lived just long enough to verify most of what I reported, and a couple of fishermen saw the Sherden sailing out of North Sound and dropping anchor at the quays. They tacked up the channel against the wind to the naval base at Colophon, where nobody believed them until they saw the column of smoke.

The cutter took me back to Colophon, where a navy sawbones patched me up, even though he wasn’t supposed to—guess why—before sending me on a supply sloop to Malata, where there’s a resident-aliens hospital licensed to treat people with chronic skin conditions, like mine. After a couple of days I was sick to death of doctors, so I discharged myself and requisitioned a lift on a charcoal cart back to the City. Soon as I got there, I was in all sorts of trouble. Commissioners of Enquiry had trekked all the way out to Malata to take my statement, and I hadn’t been there. Can’t you people do anything right?

Soon as Intelligence were through shouting at me, I tottered down the hill to see Faustinus, the City Prefect. Faustinus is—I won’t say a friend, because I don’t want to make problems for him. He has rather more time for me than most Robur, and we’ve worked together on patching up the aqueducts. Faustinus wasn’t there, called away, important meeting of the Council. I left him a note, come and see me, and dragged myself back up the hill to Municipal Works, which is sort of my home when I’m in the City.

As a special favour, obtained for me by the personal intercession of Prefect Faustinus, I had a space of my own at Municipal Works. Once upon a time it was a charcoal shed; before that, I think the watchman kept his dog there. And before that, it was part of the Painted Cloister of the Fire temple that Temren the Great built to give thanks for his defeat of the Robur under Marcian III; it’s an old city, and wherever you dig, you find things. Anyway, the Clerk of the Works let me leave some stuff there, and letters and so forth pile up in an old box by the door, and I’d made myself a bed out of three packing crates (a carpenter, remember?). I didn’t bother looking at the letters. I crawled onto the bed, smothered myself in horse blankets, and fell asleep.

Some fool woke me up. He was enormous, and head to foot in gilded scale armour, like an enormous fish standing on its tail. He wasn’t alone. “What?” I yawned.

“Colonel Orhan.”

Well, I knew that. “What?”

“General Priscus’s compliments, sir, and you’re wanted in Council.”

That, of course, was a bare-faced lie. General Priscus didn’t want me anywhere in his jurisdiction, as he’d made quite clear when I was up for my promotion (but Priscus wasn’t in charge back then, praise be). Most particularly he didn’t want me on his Council, but sadly for him, he had no choice in the matter. “When?”

“Now, sir.”

I groaned. I was still wearing the bloodstained tunic with the hole in it, over the Malata medic’s off-white bandages. “I need to get washed and changed,” I said. “Give me ten minutes, will you?”

“No, sir.”

Among the things I have room for at Municipal Works is a spare grey cloak and regulation red felt pillbox hat. I put them on—it was a hot day, I knew I’d roast in the thick wool cloak, but it was that or go into Council in bloody rags—and shuffled to my feet. The golden-fish men fell in precisely around me. No need for that, but I imagine it was just force of habit.

The War Office is four doors down from the Golden Spire, on the left. It’s a small, low door in a bleak brick wall, and once you’re through that you’re in the most amazing knot garden, all lavender and box and bewilderingly lovely flowers, and then you’re looking at the double bronze doors, with two of the toughest soldiers in the army scowling at you, and then you’re inside, shading your eyes from the glare off all that white marble. I can see why people get offended when I go in there. I don’t half lower the tone.

Still, it’s a grand view from the top. Straight down Hill Street, all you see is roofs—red tiles, grey slates, thatch. No green or blue, just the work of men’s hands, as far as the eye can see. Nowhere else on earth you can do that. Every time I look at that view, regardless of context, I realise just how lucky I am.

From the window in the Council chamber, however, you can see the sea. General Priscus was sitting with his back to it, while I had the prime lookout position. Over his shoulder, I could see the arms of the harbour, and, beyond that, flat dark blue. Plenty of sails, but none of them the red and white stripes of the Sherden. Not yet, at any rate. If I’d offered to swap places with the general, he’d have thought I was trying to be funny, so I kept my mouth shut.

In terse, concise military language, General Priscus proceeded to tell us everything we already knew; a surprise attack by seaborne aggressors, no survivors, considerable damage to buildings and stores, enquiries continuing to ascertain the identity of the attackers—

“Excuse me,” I said.

Out of the corner of my eye, I saw Prefect Faustinus wince. As well he might. He’s told me, over and over again, don’t make trouble. He’s quite right and has my best interests at heart. He keeps asking me, why do you do it? Answer: I have no idea. I know it’s going to end badly, and God knows I don’t enjoy it. My knees go weak, I get this twisting pain in my stomach and my chest tightens up so I can barely breathe. I hear my own voice speaking and I think: not now, you fool, not again. But by then it’s too late.

Everybody was looking at me. Priscus scowled. “What?”

“I know who they were,” I said.

I’d done it again. “You do.”

“Yes. They’re called the Sherden.”

When Priscus got angry, he lowered his voice until he practically purred. “Is there any reason why you didn’t see fit to mention this earlier?”

“Nobody asked me.”

Faustinus had his eyes tight shut. “Well,” said the general, “perhaps you’d be good enough to enlighten us now.”

When I’m nervous, I talk a lot. And I’m rude to people. This is ridiculous. Other times—when I’m angry, particularly when people are trying to provoke me, I can control my temper like a charioteer in the Hippodrome manages his horses. But panic makes me cocky; go figure. “Of course,” I said. “The Sherden are a loose confederation, mostly exiles and refugees from other nations, based around the estuary of the Schelm in south-eastern Permia. We tend to call them pirates but mostly they trade; we do a lot of business with them, direct or through intermediaries. They have fast, light ships, low tonnage but sturdy. Typically they only go thieving when times are hard, and then they pick off small, easy targets where they can be sure of a good, quick return—monasteries, absentee landlords’ villas, occasionally an army payroll or a wagon train of silver ore from the mines. Given the choice, though, they’d rather receive stolen goods than do the actual robbing; they know we could stamp them flat in two minutes if we wanted to. But we never have, because, like I said, we do a lot of business with them. Basically, they’re no bother to anyone.”

Admiral Zonaras leaned forward and glared up the table at me. “How many ships?”

“No idea,” I said, “it’s not my area of expertise, all I know about these people is from—well, our paths have crossed, let’s say. Naval Intelligence is bound to know. Ask them.”

Zonaras never cared for me at the best of times. “I’m asking you. Your best guess.”

I shrugged. “At any one time, total number around three fifty, four hundred ships. But you’re talking about dozens of small independent companies with no overall control. There’s no King of the Sherden or anything like that.”

Priscus looked past me down the table. “Do we have any figures for the number of ships at Classis?”

Nobody said anything. A marvellous, once-in-a-lifetime chance for me to keep my mouth shut. “About seventy,” I said.

“Hold on.” Sostratus, the Lord Chamberlain. If we’d been discussing a civilian issue, he’d have been in the chair instead of Priscus. “How do you know all this?”

I did my shrug. “I was there.”

“You what?”

Nobody knew. For crying out loud. “I was there,” I repeated. “I was at Classis on business, I saw the whole thing.” Muttering up and down the table. I pressed on. “My estimate of seventy is based on a direct view of their ships tied up at the docks. There were a dozen ships each side of each of the three jetties. Six twelves are seventy-two. I don’t think there could have been more than that when I looked, because there didn’t seem to be room, all the berths were full. They could have had more ships standing by to come in as others finished loading, I don’t know. I couldn’t see that far from where I was.”

Symmachus the Imperial agent said, “Why weren’t we told there was an eye witness?”

That didn’t improve the general’s temper. “The witness hasn’t seen fit to mention it until now, apparently. Still, better late than never. You’d better tell us all about it.”

I was about to point out that I’d made a full deposition in the naval hospital at Colophon. I think Faustinus can read my mind sometimes. I saw him shake his head, vigorously, like a cow being buzzed by flies. He had a point. So I told them the whole tale, from seeing the smoke to being picked up by the cutter. I stopped. Long silence.

“It all seems fairly straightforward to me,” said Admiral Zonaras. “I can have the Fifth Fleet at sea in four days. They’ll make sure these Sherden never bother us again.”

A general nodding, like the wind swaying a maple hedge. I could feel the blood pounding at the back of my head. Don’t say it, I begged myself. “Excuse me,” I said.

After the Council broke up, I tried to sneak away down Hillgate, but Faustinus was too quick for me. He headed me off by the Callicrates fountain. “Are you out of your tiny mind?” he said.

“But it’s true,” I told him.

He rolled his eyes at me. “Of course it’s true,” he said, “that’s not the point. The point is, you’ve pissed off everyone who matters a damn.”

Shrug. “They never liked me anyway.”

“Orhan.” Nobody calls me that. “You’re a clever man and you use your brain, which makes you unique in this man’s town, but you’ve got to do something about your attitude.”

“Attitude? Me?”

Why was I annoying the only man in the City who could stand the sight of me? Sorry, don’t know. “Orhan, you’ve got to do something about it, before you get yourself in serious trouble. You know your problem? You’re so full of resentment it oozes out of you, like a cow that hasn’t been milked. You put people’s backs up, and then they’d rather die than do what you tell them, even though it’s the right and sensible thing. You know what? If the empire comes crashing down, it could easily be all your fault.”

And that was me told. I nodded. “I know,” I said. “I fuck up good advice by giving it.” That made him grin, in spite of himself. “What I ought to do is get someone else, someone who’s not a total liability, to say things for me. Then people would listen.”

His face went sort of wooden. “I don’t know about that,” he said. “If only you could learn not to be so bloody rude.”

I sighed. “You look like you could use a drink.”

Faustinus always looks that way. This time, though, he shook his head. “Too busy,” he said, meaning too busy to risk being seen in public with me for at least a week. “Think about it, for crying out loud. Please. There’s too much at stake to risk screwing things up just because of your unfortunate personality.”

Fair comment, and I did actually think seriously about it, all the way down Hill Street. The trouble was, I’d been right. All I’d done was point out that the Fifth Fleet wouldn’t be going anywhere, not for quite some time. Admiral Zonaras had said that that was news to him; I pointed out that, since all the rope and all the barrel staves—that was what was in the shed next to the rope store, I learned that in the navy hospital, before they threw me out—for the entire navy had gone up in smoke—

Hang on, you’re saying, so maybe I should explain. They called it need-to-use stockholding, and they reckoned it saved the navy a fortune each year. The idea being, we had six fleets of three hundred and twenty ships each back then, and a ship on its own is not much use; you need masts, sails, oars, ropes, all manner of stores, of which the most important are barrels, for holding fresh water. Without water barrels, a ship can’t go out of sight of land, because of the need to tank up once a day, twice in hot weather. Now, if every single ship in the Fleet had to have its own separate set of gear—you’re probably better at sums than me, you work it out—that’s a lot of very expensive equipment, and since most of the time only two of the fleets, three in emergencies, are at sea at any given time; and since the navy yards had been to enormous trouble to make sure that everything was interchangeable, ship to ship—it was quite a coup on the part of the government official who thought of it. One fleet—the Home Division, which is on permanent duty guarding the straits—was fully equipped at all times. The other five shared two complete sets of gear, which for convenience and ease of speedy deployment were kept in store at Classis, ready to be issued at a moment’s notice when someone needed to use them.

Obviously Zonaras knew all that, at some level. But it’s perfectly possible to know something and not think about it. Or maybe the admiral was well aware that he couldn’t launch a single ship, now that all his ropes and all his barrel staves were just so much grey ash, but he didn’t want the rest of the Council in on the secret. In any event, he called me a damned liar and a bloody fool and various other things, all of them perfectly true but hardly relevant. General Priscus asked him straight out: can you send a fleet to Permia or can’t you? So Zonaras did the only thing he could, in the circumstances. He jumped up, gave me a scowl that made my t. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...