- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

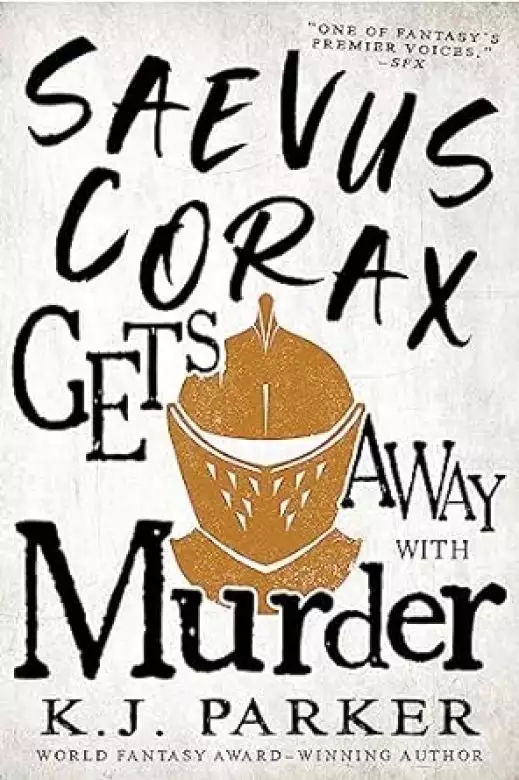

Synopsis

From one of the most original voices in fantasy comes a heart-warming tale of peace, love, and battlefield salvage.

If you’re going to get ahead in the battlefield salvage business, you have to regard death as a means to an end. In other words, when the blood flows, so will the cash. Unfortunately, even though war is on the way, Saevus Corax has had enough.

There are two things he has to do before he can enjoy his retirement: get away with one last score, and get away with murder. For someone who, ironically, tends to make a mess wherever he goes, leaving his affairs in order is going to be Saevus Corax’s biggest challenge yet.

If you’re going to get ahead in the battlefield salvage business, you have to regard death as a means to an end. In other words, when the blood flows, so will the cash. Unfortunately, even though war is on the way, Saevus Corax has had enough.

There are two things he has to do before he can enjoy his retirement: get away with one last score, and get away with murder. For someone who, ironically, tends to make a mess wherever he goes, leaving his affairs in order is going to be Saevus Corax’s biggest challenge yet.

For more from K. J. Parker, check out:

Sixteen Ways to Defend a Walled City

How to Rule an Empire and Get Away With It

A Practical Guide to Conquering the World

A Practical Guide to Conquering the World

The Two of Swords

The Two of Swords: Volume One

The Two of Swords Volume Two

The Two of Swords: Volume Three

The Fencer Trilogy

Colours in the Steel

The Belly of the Bow

The Proof House

The Scavenger Trilogy

Shadow

Pattern

Memory

Engineer Trilogy

Devices and Desires

Evil for Evil

The Escapement

The Company

The Folding Knife

The Hammer

Sharps

Release date: December 5, 2023

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

Saevus Corax Gets Away With Murder

K.J. Parker

Isn’t it nice, I remember thinking as I tried to yank an arrow out of a dead soldier’s eye, when things unexpectedly turn out just right? And then the arrow came away in my hand, but the eyeball was firmly stuck on the arrowhead. I glared at it. A standard hunting broadhead, with barbs, which was why it had dragged the eye out of its socket. I could cut it away with a knife, but could I really be bothered, for an arrow worth five trachy?

Everything about this job (apart from the flies, the mosquitos, the swamp and the quite appalling smell) had been roses all the way. For a start, Count Theudebert had paid me, rather than the other way around. In my business – I clear up after battles – you have to pay the providers, meaning the two opposing armies, for the privilege of burying their dead, in return for what you can strip off the bodies. Since we’re a relatively small concern and the big boys (mostly the Asvogel brothers) outbid us for pretty well every job worth having, we tend to get contracts with wafer-thin margins, and our profits are generally more a state of mind rather than anything you can write down on a balance sheet, let alone spend. But the Count had written to me offering me a flat-rate fee for clearing up the mess he intended to make in the Leerwald forest, plus anything I found that I might possibly want to keep. That sort of deal doesn’t come along every day, believe me.

I could see where the Count was coming from. Five thousand or so of his tenants, living in a clearing in the vast expanse of the Leerwald, had decided not to pay their rent and had killed the men he’d sent to help them reconsider their decision; accordingly, he had no choice but to march in there, slaughter everything that moved and find or buy new tenants to replace the dead. The tenants didn’t own anything worth having, so no reputable battlefield clearance contractor would want the job on the usual terms. Either the Count would have to do his own clean-up, or he’d have to hire someone.

He wasn’t exactly offering a fortune, but times were hard and we needed the work. Also, as my good friend and junior partner Gombryas pointed out, chances were that the Count’s archers would probably do a fair amount of the slaughtering, which would mean arrows… Nothing but the best for Theudebert of Draha, so they’d be bound to be using good-quality hard-steel bodkins on ash shafts with goose fletchings – again, not exactly a fortune but worth picking up, and if what people were saying was true, about a big war brewing in the east, the price of high-class once-used arrows could only go up. Also, he added, according to the Count’s letter there’d be dead civilians as well, and even peasant women tend to have some jewellery, even if it’s just whittled bone on a bit of string. And shoes, he added cheerfully: everybody wears shoes. At a gulden six per barrelful, it all adds up…

Gombryas had been right about one thing. There were plenty of arrows. But they turned out to be practically worthless, which was wonderful—

“Over here,” Gombryas yelled. “I found him!”

I chucked the arrow with the eyeball on it and shoved my way through the briars to where Gombryas was standing, at the foot of a large beech tree. Its canopy overshadowed an area of about twenty square yards, forming a welcome clearing. Nailed to the trunk of the tree was a man’s body. He’d been ripped open, his ribcage prised apart and his guts wound out round a stick. Piled at his feet were his clothes and armour: gorgeous clothes and luxury armour. Nothing but the best for Theudebert of Draha.

“Charming,” I said.

Gombryas grinned at me. “I guess they didn’t like him much,” he said. “Can’t say I blame them.”

He had a pair of clippers in his hand, the sort you use for shearing sheep or pruning vines. I could see he was torn with indecision. Gombryas collects relics of dead military heroes; relics as in body parts. His collection is the ruling passion of his life. Mostly he buys them for ridiculous sums of money from dealers and other collectors, and he’s not a rich man, so he finances his collection by harvesting and selling bits and pieces whenever we come across a dead hero in the usual course of our business. Theudebert was definitely in the highly sought-after category. Hence the agonising decision: which bits to sell and which bits to keep for himself?

The point being, Theudebert had lost. He’d led his army into the Leerwald, knowing that his tenants were forbidden to own weapons and therefore expecting, reasonably enough, not to have to do any actual fighting, just killing. What he’d overlooked was the tendency of forests to contain trees, which any fool with a few basic hand tools can turn into a functional bow in the course of an afternoon… Tracing the sequence of events by means of the position of the bodies, I figured out that Theudebert was only about half a mile from the first of the villages when he walked into the first ambush. About a third of his men were shot down in what could only have been a matter of a minute or so. Understandably he decided to turn back, figuring that the tenants had made their point. He was wrong about that. There were further ambushes, about a dozen of them, strung out over about five miles of forest trail. Finally, Theudebert had turned off the road and tried to get away through the dense thickets of briars, holly and withies which had grown up where his late father had cleared a broad swath of the forest for charcoal-burning. The beech tree was, I assumed, the place where the tenants had finally caught up with him and his few surviving guards.

“Will you look at the quality of this stuff?” Olybrius said, waving a bloodstained shirt under my nose. “That’s best imported linen.”

“It’s got a hole in it,” I said.

Olybrius gave me a look. “Funny man,” he said. “And you should see the boots. Double-seamed, and hardly a mark on them.”

I should’ve been as delighted as he was, but somehow I wasn’t. I wasn’t unhappy, either. We’d lucked into a substantial windfall, at a time when we badly needed one, and for once the work wouldn’t be particularly arduous (except for the flies, the mosquitos, the swamp and the truly horrible smell) – and, God only knows, my heart wasn’t inclined to bleed for Count Theudebert, even though he was a sort of relation of mine, second cousin three times removed or something like that. Quite the opposite; when you’ve spent your life either imposing authority or having it imposed upon you, the sight of a head of state nailed to a tree with his guts dangling out can’t fail to restore your faith in the basic rightness of things. Just occasionally, you can reassure yourself, the bullies get what’s coming to them, so everything’s fine.

I decided that whatever was bothering me couldn’t be terribly important, and got on with the work I was supposed to be doing. Since I’m nominally the boss of the outfit, it’s more or less inevitable that I get the lousiest job, which in our line of business is collecting up the bodies, once they’ve been stripped of armour and clothing and thoroughly gone over for small items of value, and disposing of them. Usually we burn them, but in a dense forest packed with underbrush it struck me that that mightn’t be a very good idea. That meant digging a series of large holes, a chore that my colleagues and I detest.

Especially in a forest. It’s the nature of things that forests grow on thin, stony soil; if there was good soil under there, you can bet someone would’ve been along to cut down the trees and plough it up a thousand years ago. Typically there’s about a foot of leaf mould, really hard to dig into because of the network of holly, ground elder and bramble roots. Under that you find about ten inches of crumbly black soil, along with a lot of stones. Then you’re down into clay, if you’re lucky, or your actual rock if you aren’t. On this occasion Fortune smiled on us and we found clay, thick and grey and sort of oily, which we laboriously chopped out with pickaxes. Two feet down into the clay, of course, we struck the water table, which turned our carefully dug graves into miniature wells in no time flat. Still, we were only burying dead soldiers, so who cares? Let them get wet.

Gombryas and Olybrius had finished stripping the bodies and loading the proceeds on to carts long before we got our pits done, so they and their crews gathered round to give us moral support while we dug. I was up to my waist in filthy water, I remember, with Gombryas perched on the edge of the grave explaining to me the finer points of relic collecting. For instance: singletons – organs of which there are only one, such as the nose, the heart and the penis – are obviously more valuable than multiples (fingers, toes, ears, testicles), but complete sets of fingers, toes, ears &c are more valuable still. But you can make a real killing if a rich collector has got nine of so-and-so’s fingers and you’ve got the missing one, which he needs to make up the set. Accordingly, after much deliberation, Gombryas had decided to keep Count Theudebert’s heart and liver (preserved in honey) and one finger; the rest of the internals and extremities would probably be alluring enough as swapsies to net him either the complete left hand of Carnufex the Irrigator – with most of the skin still on, he told me breathlessly, which is practically unheard of for a Warring States-era relic – or the left ear of Prince Phraates; he already had the right ear, but the First Social War wasn’t really his period, so the plan was to swap both ears for the pelvis of Calojan the Great, which he knew for a fact was likely to come up at some point in the next year or so, because the man who owned it had a nasty disease and wasn’t expected to live…

“Gombryas,” I interrupted. “How much is your collection worth?”

He stopped and looked at me. “No idea,” he said.

“At a rough guess.”

He thought for a while, during which time he didn’t speak, which was nice. “Fifty thousand,” he said eventually. “Well, maybe closer to sixty. Depends on what the market’s doing at the time. Why?”

I was mildly stunned. “Fifty thousand staurata,” I said. “And you’re still here, doing this shit.”

He was shocked, and offended. “I’d never sell my collection,” he said. “It’s taken me a lifetime—”

“Seriously,” I said. “All those bits of desiccated soldiers are worth more to you than a life of security and ease. Fifty thousand—”

“Keep your voice down,” he hissed at me.

“Sorry,” I said. I straightened my back and rested for a moment, leaning on the handle of my shovel. “But for crying out loud, Gombryas, that’s serious money. You could buy two ships and still have enough left for a vineyard.”

“It’s not about money.” This from a man who regularly went through the ashes of our cremation pyres with a rake, to retrieve arrowheads left inside the bodies. “It’s about, I don’t know, heritage—”

“Talking of which,” I said. “You’ve got no family. When you die, who gets all the stuff?”

He shrugged. “I don’t know, do I? None of my business when I’m dead.”

“Maybe,” I suggested, “your fellow collectors will cut you up and share you out. Wouldn’t that be nice?”

He scowled at me. “Funny man,” he said.

I gave him a warm smile and started digging. Quite by accident, I made a big splash in the muddy water with the blade of my shovel, and Gombryas’s legs got drenched. He called me something or other and went away.

Six feet deep is the industry standard, but I decided I’d exercise my professional discretion and make do with four. I called a halt, we scrambled up out of the graves and started tipping the bodies. They rolled off the tailgates of the carts and went splash into the water, displacing most of it in accordance with Saloninus’s Third Law, and then we filled in, making an eighteen-inch allowance for settlement. Not that it mattered a damn in the middle of a forest, and we’d been paid in advance by a man who was now exceptionally dead, but there’s a right way and a wrong way of doing things, and I hate it when Chusro Asvogel goes around making snide remarks about the quality of our work.

So that was that. We loaded our tools on to the carts and made our way back to the forest road. It was blocked with fallen trees.

Not so much fallen, I noted after a cursory examination, as chopped down. I started shouting the usual stuff about shunting the carts into a square, horses and people in the middle, but nobody seemed to be paying attention. That, I soon gathered, was because they were looking at the archers who’d suddenly appeared out of the trees, and were standing there looking at us.

Nuts, I thought. But I put a trustworthy look on my face and walked towards the treeline. “Can I help you gentlemen?” I said.

A man came forward. He was being helped by two others, and his left leg dangled, the way they do when they’re broken. “Who the hell are you?” he said.

I explained. He looked at me. “Seriously?”

“It’s what we do for a living.” I paused. These, presumably, were the people who’d just shot to death a famous general and six thousand trained soldiers. “Morally,” I said, “I guess the stuff belongs to you, but we’ve just done a hell of a lot of work, so—”

“We don’t want any of that,” the man said.

I can’t say I warmed to him straight away. I guess he looked the way you’d expect a man to look when he’s just miraculously won a battle he really didn’t want to fight. I’d put him a few years either side of sixty, but men age quickly when they’re tenants of someone like Theudebert; a short man, slight, bald, with a wispy white beard. “Are you sure?” I said.

“I just said so, didn’t I? You keep it. Sell it. Just go away.”

Which was exactly what I wanted to hear; more, I guess, than I deserved. “How about the weapons?” I said. “There’s spears, shields, helmets, some body armour.”

“Are you deaf?”

“For when they come back,” I explained. “You’ll need weapons then.”

He frowned. “They won’t come back,” he said.

“Want to bet?” Shut up, my inner voice yelled at me, sounding remarkably like my mother. “You killed the Count and six thousand men—”

“No.” He looked at me. “That many?”

“Six thousand, one hundred and fourteen,” I said. “Of course they’ll be back. You’ve got to be punished. Otherwise, the whole doctrine of the monopoly of force falls apart.”

“The what?”

I may be many things, but I’m not an educator. I have better things to do than spread enlightenment. “At the very least,” I said, “keep the bows. They’re standard Aelian issue, top of the line, about the best you can get unless you upgrade to composite. Keep them and practise with them, and when the bastards come back, wearing proper armour instead of just skirmishing kit, at least you’ll be able to make a fight of it. Your homebrew bows simply don’t have the cast to shoot through plate armour, or lamellar.”

He had no idea what I was talking about. “I told you,” he said. “We don’t want their garbage. And we don’t want you. Go away.”

“Fine,” I said. “And thank you. But trust me, they will be back.” I wasn’t getting through to him. Besides, it wasn’t any of my business. “Make yourselves stronger bows,” I told him. “Practise.”

“Get lost.”

None of my business, after all. I smiled and walked away. “Well?” Gombryas said in my ear, in a whisper they could’ve heard in Boc Bohec.

“It’s fine,” I told him. “They don’t want the stuff.”

“Really?”

“Really,” I told him. “Let’s get out of here before they change their minds.”

So we did that, and pretty soon we were out of the forest and back into the light, which made me nervous. I didn’t know if the Count’s people had heard the news yet; probably not. As soon as they found out what had happened, they’d be busy. Also, most likely, they’d want their weapons and armour back. “For all we know,” I told Gombryas and Olybrius, as we rattled along the main road to the sea, “that was history in the making. You can tell your grandchildren you were there.”

“Tell them what?”

Indeed. The Count would be back, a new man with a new army, more soldiers, better weapons; they’d have a strategy this time, and they’d win. The tenants would be slaughtered and replaced, the rule of law would be upheld, future generations would grow up secure in the thoroughly reinforced knowledge that you can’t fight City Hall. Definitely none of my business.

(Oh, did I mention I’m the son of a duke? Not that it’s ever done me any good, since I left home under something of a cloud when I was fifteen, and shortly after that my father put a price on my head, forty thousand staurata dead or alive – which sounds impressive, but it’s rather less than my sister and brother-in-law are offering, on the same terms; of course, my brother-in-law is the Elector, so he can afford to pay top dollar. But heredity definitely ought to put me on the side of the landlord against the tenant, capital against labour, divine right against malcontents and Bolsheviks; and I’ve seen the mess that tenantry, labour and Bolshevism have made of things when they’ve been given the chance, every bit as bad as the mess they rebelled against. Accordingly I tend not to think in terms of monolithic blocs, idealisms and ethical systems. The world makes more sense, I find, if you interpret it in terms of idiots and bastards. And if you ask me which category I fall into, I freely admit: both. My father, by the way, is a much less amenable landlord than cousin Theudebert was. I kid myself that I’m liberal and enlightened but I don’t suppose I’d be significantly better, in the incredibly unlikely event that I get the chance to find out.)

We sold the stuff at Holdeshar for rather more than I’d anticipated. We got the going rate for the clothes, a very good price for the boots, shields and helmets and silly money for the bows and arrows. Dealers I’d known for years suddenly gave me big smiles for the first time ever, and asked if there was any more where that came from. Needless to say I said yes, though I was lying. How soon can you deliver? they asked. That made me feel uncomfortable. Maybe there really was going to be a war, after all.

There’s always a war: it goes without saying. Every day of every year since the Invincible Sun moulded the first man out of river mud and propped him against a tree to dry, there’s been a war somewhere – little wars, silly little wars, scraps over boundaries and trade, cattle raids and state-sponsored piracy, scalp hunts, punitive expeditions, reprisals for reprisals for reprisals, pre-emptive reprisals for diplomatic snubs that haven’t even happened yet… Little wars keep me fed and clothed and busy, and being busy is good because it doesn’t leave me any time to brood on how badly I’ve screwed up my life. But big wars – the major empires and federations up on their hind legs ripping out each other’s throats – are mercifully rare: once in a generation, which is why there are still human beings, and why the entire surface of the earth isn’t covered in briars and withies. About the only thing I can say for myself is that I’ve stopped two big wars from happening, the Sashan Empire against the West; me, with my two grubby hands and my poor overworked brain, even though strictly speaking it was none of my business. I guess I don’t approve of war. Burning and burying bodies and tracking my next job of work by a trail of burned farmhouses has led me to certain conclusions. I won’t attempt to defend them, since there are all sorts of good arguments for war, devised by some of our species’ finest minds, and I wouldn’t presume to contradict them. I always come back to Saloninus’s definition of a sword – a piece of metal with a slave on both ends.

There are worse places than Holdeshar, at least a dozen of them. We chose the back bar of the Humility Exalted for the shareout. The drill is, I find the buyers and do the selling, deduct the overheads and the running costs and divide up the balance between the heads of department according to the established ratio: 10 per cent for me; 10 per cent for each department. It was nice to have something tangible to hand out for a change. For the last three jobs we’d done, they’d had to make do with fine words and promises.

I left the rest of them in the Humility and crossed the road to the Temple. The local branch of the Knights of Equity have an office there, in a small room behind the high altar. Before they were a bank, the Knights were crusaders, fighting to free the holy places from the Sashan and the Antecyrenaeans. In the end their army was slaughtered to the last man, but their fundraising arm somehow neglected to show up for the final battle, and they were left orphaned, without a reason for existing but with a very great deal of other people’s money, which they were naturally reluctant to hand back. So they reinvented themselves as a general charitable fund, although for various reasons they never got around to distributing anything. Now they’re the biggest bank in the West, slightly ahead of the Poor Sisters. They’ve tried to have me murdered more than once but I still bank with them, mostly because the only alternative would be the Sisters, who don’t like me one bit. Most of the other banks went belly-up during the financial crisis, which I caused by encouraging the Sashan to annex the fabulously wealthy island of Sirupat; I was king of Sirupat at the time (don’t ask: it’s complicated). Anyway, these days there are only two real players in the money game, both of them shadows of their former pre-crisis selves, but definitely still going and about as trustworthy as a scorpion. Which isn’t a bad thing; you can always trust a scorpion to sting you, if you provoke it.

The chief clerk of the Knights in Holdeshar is an old friend of mine. She looked up as I walked in. “Get out,” she said.

“Don’t be like that,” I said. “I’m paying in.”

“Get out,” she repeated, “before I call the guards.”

“They’re in the Humility,” I told her. “My boys are buying them drinks. Come on, Lessa, be nice. Bearing grudges doesn’t suit you.”

“Piss off and die,” said my friend, then she shrugged. “Paying in?”

“One thousand staurata, cash money.”

I wouldn’t say she actually softened, but she reached for her ledger and opened it. She’s a tall, thin woman, maybe just this side of sixty, sharp as a knife; she used to be a Sister until she had to quit the order under a bit of a cloud, something about a certain sum of money not being where it should have been. The Knights were glad to have her because of her comprehensive knowledge of where the Sisters had buried various bodies. Ending up in Holdeshar was a matter of choice rather than rotten luck or prejudice; she claims to value the simple, quiet life, which I guess I can understand.

She ruled a line across the page, then looked at me. “Go on, then,” she said. “Let’s see it.”

I had the money in a satchel under my coat, which I took off and hung on a hook behind the door. I dumped the satchel on the desk and opened it. She wrinkled her nose. “It smells,” she said.

“That’s the bag,” I explained. I’d taken it from round the neck of one of Theudebert’s adjutants. Waste not, want not.

“Why is everything to do with you always so horrible?”

I shrugged. “Beats me,” I said, and emptied the bag on to the desk. She scrabbled the coins towards her and started to count.

You don’t dare talk to Lessa while she’s counting. When she’d finished and reluctantly conceded that it was all there, I said, “You know all about politics and stuff. Is there going to be a war?”

She thought for a moment. “Not sure,” she said.

“Not sure yes or not sure no?”

“Not sure,” she said. “The Aelians want one, but the Sashan don’t. At least, they don’t want one now, not with all the problems they’ve got at home—”

“What problems?”

“But on the other hand, if they have a war now they’ll almost certainly win, but if they wait six months or a year the Aelians stand a much better chance of at least making a fight of it. Which is why I’m not sure, like I told you.”

“What problems?”

She grinned at me. “Oh, it’s all just rumour and speculation. Besides, it’s restricted information, favoured customers only. Sorry.”

“I’ve just paid in a thousand staurata.”

“Yes, but I don’t like you. Here’s your receipt. I’ll have the letter of credit sent to your branch at Auxentia. Goodbye.”

I went back to the Humility. Olybrius and Carrhasio were working up to one of their usual drunken shouting matches. Polybius had ordered the house special, which was something grey with bits in it. Gombryas was talking intensely to a fat man who was almost certainly a fellow collector; next to his elbow on the bar was an ominous looking clay pot, sealed with resin. I considered asking the landlord to bring me a pot of green-leaf tea, but decided I couldn’t be bothered. Then the man I’d arranged to meet came in, and we sat down in the quiet corner, furthest away from the door.

“Twelve thousand staurata,” he said. “Take it or leave it.”

It was a modest little war, more of a police action, in Cheuda, which is a nice enough place if you like that sort of thing: flat, which is good from the haulage point of view, but inland, which isn’t. He was representing the rebels, who were quietly confident of victory; tomorrow I’d be meeting the government, who were equally confident but likely to be more noisy. “Ten,” I said.

“I’ve got a firm offer of eleven from the Asvogel brothers.”

“Take it,” I said. “They’re a good firm, very reliable. And they can afford to work on wafer-thin margins. We can’t.”

He looked at me. I knew for a fact that Chusro Asvogel had offered him nine fifty, because Chusro told me so himself. “We prefer to work with smaller operators,” he said. “Match the Asvogels’ eleven thousand and the job’s yours.”

“I’ll match their nine fifty, with pleasure. That’s actually less than I offered you a moment ago, but that’s fine by me.”

I think he’d made up his mind that he didn’t like me. “Ten thousand staurata.”

“Nine seven-five,” I said, “and that’s my final offer.”

“You said ten a moment ago.”

“Times change.” I waited three seconds, then grinned at him. “All right, ten,” I said. “After all, that’s what the job’s actually worth to me. Does that sound fair to you?”

He sighed. “I hate bargaining,” he said.

“You’re not very good at it,” I told him. “But then, why should you be? You’re an idealist.”

That made him grin. He still didn’t like me very much. “Damn right,” he said. “When you’re building the Great Society, every compromise is a betrayal.”

“Of course it . . .

Everything about this job (apart from the flies, the mosquitos, the swamp and the quite appalling smell) had been roses all the way. For a start, Count Theudebert had paid me, rather than the other way around. In my business – I clear up after battles – you have to pay the providers, meaning the two opposing armies, for the privilege of burying their dead, in return for what you can strip off the bodies. Since we’re a relatively small concern and the big boys (mostly the Asvogel brothers) outbid us for pretty well every job worth having, we tend to get contracts with wafer-thin margins, and our profits are generally more a state of mind rather than anything you can write down on a balance sheet, let alone spend. But the Count had written to me offering me a flat-rate fee for clearing up the mess he intended to make in the Leerwald forest, plus anything I found that I might possibly want to keep. That sort of deal doesn’t come along every day, believe me.

I could see where the Count was coming from. Five thousand or so of his tenants, living in a clearing in the vast expanse of the Leerwald, had decided not to pay their rent and had killed the men he’d sent to help them reconsider their decision; accordingly, he had no choice but to march in there, slaughter everything that moved and find or buy new tenants to replace the dead. The tenants didn’t own anything worth having, so no reputable battlefield clearance contractor would want the job on the usual terms. Either the Count would have to do his own clean-up, or he’d have to hire someone.

He wasn’t exactly offering a fortune, but times were hard and we needed the work. Also, as my good friend and junior partner Gombryas pointed out, chances were that the Count’s archers would probably do a fair amount of the slaughtering, which would mean arrows… Nothing but the best for Theudebert of Draha, so they’d be bound to be using good-quality hard-steel bodkins on ash shafts with goose fletchings – again, not exactly a fortune but worth picking up, and if what people were saying was true, about a big war brewing in the east, the price of high-class once-used arrows could only go up. Also, he added, according to the Count’s letter there’d be dead civilians as well, and even peasant women tend to have some jewellery, even if it’s just whittled bone on a bit of string. And shoes, he added cheerfully: everybody wears shoes. At a gulden six per barrelful, it all adds up…

Gombryas had been right about one thing. There were plenty of arrows. But they turned out to be practically worthless, which was wonderful—

“Over here,” Gombryas yelled. “I found him!”

I chucked the arrow with the eyeball on it and shoved my way through the briars to where Gombryas was standing, at the foot of a large beech tree. Its canopy overshadowed an area of about twenty square yards, forming a welcome clearing. Nailed to the trunk of the tree was a man’s body. He’d been ripped open, his ribcage prised apart and his guts wound out round a stick. Piled at his feet were his clothes and armour: gorgeous clothes and luxury armour. Nothing but the best for Theudebert of Draha.

“Charming,” I said.

Gombryas grinned at me. “I guess they didn’t like him much,” he said. “Can’t say I blame them.”

He had a pair of clippers in his hand, the sort you use for shearing sheep or pruning vines. I could see he was torn with indecision. Gombryas collects relics of dead military heroes; relics as in body parts. His collection is the ruling passion of his life. Mostly he buys them for ridiculous sums of money from dealers and other collectors, and he’s not a rich man, so he finances his collection by harvesting and selling bits and pieces whenever we come across a dead hero in the usual course of our business. Theudebert was definitely in the highly sought-after category. Hence the agonising decision: which bits to sell and which bits to keep for himself?

The point being, Theudebert had lost. He’d led his army into the Leerwald, knowing that his tenants were forbidden to own weapons and therefore expecting, reasonably enough, not to have to do any actual fighting, just killing. What he’d overlooked was the tendency of forests to contain trees, which any fool with a few basic hand tools can turn into a functional bow in the course of an afternoon… Tracing the sequence of events by means of the position of the bodies, I figured out that Theudebert was only about half a mile from the first of the villages when he walked into the first ambush. About a third of his men were shot down in what could only have been a matter of a minute or so. Understandably he decided to turn back, figuring that the tenants had made their point. He was wrong about that. There were further ambushes, about a dozen of them, strung out over about five miles of forest trail. Finally, Theudebert had turned off the road and tried to get away through the dense thickets of briars, holly and withies which had grown up where his late father had cleared a broad swath of the forest for charcoal-burning. The beech tree was, I assumed, the place where the tenants had finally caught up with him and his few surviving guards.

“Will you look at the quality of this stuff?” Olybrius said, waving a bloodstained shirt under my nose. “That’s best imported linen.”

“It’s got a hole in it,” I said.

Olybrius gave me a look. “Funny man,” he said. “And you should see the boots. Double-seamed, and hardly a mark on them.”

I should’ve been as delighted as he was, but somehow I wasn’t. I wasn’t unhappy, either. We’d lucked into a substantial windfall, at a time when we badly needed one, and for once the work wouldn’t be particularly arduous (except for the flies, the mosquitos, the swamp and the truly horrible smell) – and, God only knows, my heart wasn’t inclined to bleed for Count Theudebert, even though he was a sort of relation of mine, second cousin three times removed or something like that. Quite the opposite; when you’ve spent your life either imposing authority or having it imposed upon you, the sight of a head of state nailed to a tree with his guts dangling out can’t fail to restore your faith in the basic rightness of things. Just occasionally, you can reassure yourself, the bullies get what’s coming to them, so everything’s fine.

I decided that whatever was bothering me couldn’t be terribly important, and got on with the work I was supposed to be doing. Since I’m nominally the boss of the outfit, it’s more or less inevitable that I get the lousiest job, which in our line of business is collecting up the bodies, once they’ve been stripped of armour and clothing and thoroughly gone over for small items of value, and disposing of them. Usually we burn them, but in a dense forest packed with underbrush it struck me that that mightn’t be a very good idea. That meant digging a series of large holes, a chore that my colleagues and I detest.

Especially in a forest. It’s the nature of things that forests grow on thin, stony soil; if there was good soil under there, you can bet someone would’ve been along to cut down the trees and plough it up a thousand years ago. Typically there’s about a foot of leaf mould, really hard to dig into because of the network of holly, ground elder and bramble roots. Under that you find about ten inches of crumbly black soil, along with a lot of stones. Then you’re down into clay, if you’re lucky, or your actual rock if you aren’t. On this occasion Fortune smiled on us and we found clay, thick and grey and sort of oily, which we laboriously chopped out with pickaxes. Two feet down into the clay, of course, we struck the water table, which turned our carefully dug graves into miniature wells in no time flat. Still, we were only burying dead soldiers, so who cares? Let them get wet.

Gombryas and Olybrius had finished stripping the bodies and loading the proceeds on to carts long before we got our pits done, so they and their crews gathered round to give us moral support while we dug. I was up to my waist in filthy water, I remember, with Gombryas perched on the edge of the grave explaining to me the finer points of relic collecting. For instance: singletons – organs of which there are only one, such as the nose, the heart and the penis – are obviously more valuable than multiples (fingers, toes, ears, testicles), but complete sets of fingers, toes, ears &c are more valuable still. But you can make a real killing if a rich collector has got nine of so-and-so’s fingers and you’ve got the missing one, which he needs to make up the set. Accordingly, after much deliberation, Gombryas had decided to keep Count Theudebert’s heart and liver (preserved in honey) and one finger; the rest of the internals and extremities would probably be alluring enough as swapsies to net him either the complete left hand of Carnufex the Irrigator – with most of the skin still on, he told me breathlessly, which is practically unheard of for a Warring States-era relic – or the left ear of Prince Phraates; he already had the right ear, but the First Social War wasn’t really his period, so the plan was to swap both ears for the pelvis of Calojan the Great, which he knew for a fact was likely to come up at some point in the next year or so, because the man who owned it had a nasty disease and wasn’t expected to live…

“Gombryas,” I interrupted. “How much is your collection worth?”

He stopped and looked at me. “No idea,” he said.

“At a rough guess.”

He thought for a while, during which time he didn’t speak, which was nice. “Fifty thousand,” he said eventually. “Well, maybe closer to sixty. Depends on what the market’s doing at the time. Why?”

I was mildly stunned. “Fifty thousand staurata,” I said. “And you’re still here, doing this shit.”

He was shocked, and offended. “I’d never sell my collection,” he said. “It’s taken me a lifetime—”

“Seriously,” I said. “All those bits of desiccated soldiers are worth more to you than a life of security and ease. Fifty thousand—”

“Keep your voice down,” he hissed at me.

“Sorry,” I said. I straightened my back and rested for a moment, leaning on the handle of my shovel. “But for crying out loud, Gombryas, that’s serious money. You could buy two ships and still have enough left for a vineyard.”

“It’s not about money.” This from a man who regularly went through the ashes of our cremation pyres with a rake, to retrieve arrowheads left inside the bodies. “It’s about, I don’t know, heritage—”

“Talking of which,” I said. “You’ve got no family. When you die, who gets all the stuff?”

He shrugged. “I don’t know, do I? None of my business when I’m dead.”

“Maybe,” I suggested, “your fellow collectors will cut you up and share you out. Wouldn’t that be nice?”

He scowled at me. “Funny man,” he said.

I gave him a warm smile and started digging. Quite by accident, I made a big splash in the muddy water with the blade of my shovel, and Gombryas’s legs got drenched. He called me something or other and went away.

Six feet deep is the industry standard, but I decided I’d exercise my professional discretion and make do with four. I called a halt, we scrambled up out of the graves and started tipping the bodies. They rolled off the tailgates of the carts and went splash into the water, displacing most of it in accordance with Saloninus’s Third Law, and then we filled in, making an eighteen-inch allowance for settlement. Not that it mattered a damn in the middle of a forest, and we’d been paid in advance by a man who was now exceptionally dead, but there’s a right way and a wrong way of doing things, and I hate it when Chusro Asvogel goes around making snide remarks about the quality of our work.

So that was that. We loaded our tools on to the carts and made our way back to the forest road. It was blocked with fallen trees.

Not so much fallen, I noted after a cursory examination, as chopped down. I started shouting the usual stuff about shunting the carts into a square, horses and people in the middle, but nobody seemed to be paying attention. That, I soon gathered, was because they were looking at the archers who’d suddenly appeared out of the trees, and were standing there looking at us.

Nuts, I thought. But I put a trustworthy look on my face and walked towards the treeline. “Can I help you gentlemen?” I said.

A man came forward. He was being helped by two others, and his left leg dangled, the way they do when they’re broken. “Who the hell are you?” he said.

I explained. He looked at me. “Seriously?”

“It’s what we do for a living.” I paused. These, presumably, were the people who’d just shot to death a famous general and six thousand trained soldiers. “Morally,” I said, “I guess the stuff belongs to you, but we’ve just done a hell of a lot of work, so—”

“We don’t want any of that,” the man said.

I can’t say I warmed to him straight away. I guess he looked the way you’d expect a man to look when he’s just miraculously won a battle he really didn’t want to fight. I’d put him a few years either side of sixty, but men age quickly when they’re tenants of someone like Theudebert; a short man, slight, bald, with a wispy white beard. “Are you sure?” I said.

“I just said so, didn’t I? You keep it. Sell it. Just go away.”

Which was exactly what I wanted to hear; more, I guess, than I deserved. “How about the weapons?” I said. “There’s spears, shields, helmets, some body armour.”

“Are you deaf?”

“For when they come back,” I explained. “You’ll need weapons then.”

He frowned. “They won’t come back,” he said.

“Want to bet?” Shut up, my inner voice yelled at me, sounding remarkably like my mother. “You killed the Count and six thousand men—”

“No.” He looked at me. “That many?”

“Six thousand, one hundred and fourteen,” I said. “Of course they’ll be back. You’ve got to be punished. Otherwise, the whole doctrine of the monopoly of force falls apart.”

“The what?”

I may be many things, but I’m not an educator. I have better things to do than spread enlightenment. “At the very least,” I said, “keep the bows. They’re standard Aelian issue, top of the line, about the best you can get unless you upgrade to composite. Keep them and practise with them, and when the bastards come back, wearing proper armour instead of just skirmishing kit, at least you’ll be able to make a fight of it. Your homebrew bows simply don’t have the cast to shoot through plate armour, or lamellar.”

He had no idea what I was talking about. “I told you,” he said. “We don’t want their garbage. And we don’t want you. Go away.”

“Fine,” I said. “And thank you. But trust me, they will be back.” I wasn’t getting through to him. Besides, it wasn’t any of my business. “Make yourselves stronger bows,” I told him. “Practise.”

“Get lost.”

None of my business, after all. I smiled and walked away. “Well?” Gombryas said in my ear, in a whisper they could’ve heard in Boc Bohec.

“It’s fine,” I told him. “They don’t want the stuff.”

“Really?”

“Really,” I told him. “Let’s get out of here before they change their minds.”

So we did that, and pretty soon we were out of the forest and back into the light, which made me nervous. I didn’t know if the Count’s people had heard the news yet; probably not. As soon as they found out what had happened, they’d be busy. Also, most likely, they’d want their weapons and armour back. “For all we know,” I told Gombryas and Olybrius, as we rattled along the main road to the sea, “that was history in the making. You can tell your grandchildren you were there.”

“Tell them what?”

Indeed. The Count would be back, a new man with a new army, more soldiers, better weapons; they’d have a strategy this time, and they’d win. The tenants would be slaughtered and replaced, the rule of law would be upheld, future generations would grow up secure in the thoroughly reinforced knowledge that you can’t fight City Hall. Definitely none of my business.

(Oh, did I mention I’m the son of a duke? Not that it’s ever done me any good, since I left home under something of a cloud when I was fifteen, and shortly after that my father put a price on my head, forty thousand staurata dead or alive – which sounds impressive, but it’s rather less than my sister and brother-in-law are offering, on the same terms; of course, my brother-in-law is the Elector, so he can afford to pay top dollar. But heredity definitely ought to put me on the side of the landlord against the tenant, capital against labour, divine right against malcontents and Bolsheviks; and I’ve seen the mess that tenantry, labour and Bolshevism have made of things when they’ve been given the chance, every bit as bad as the mess they rebelled against. Accordingly I tend not to think in terms of monolithic blocs, idealisms and ethical systems. The world makes more sense, I find, if you interpret it in terms of idiots and bastards. And if you ask me which category I fall into, I freely admit: both. My father, by the way, is a much less amenable landlord than cousin Theudebert was. I kid myself that I’m liberal and enlightened but I don’t suppose I’d be significantly better, in the incredibly unlikely event that I get the chance to find out.)

We sold the stuff at Holdeshar for rather more than I’d anticipated. We got the going rate for the clothes, a very good price for the boots, shields and helmets and silly money for the bows and arrows. Dealers I’d known for years suddenly gave me big smiles for the first time ever, and asked if there was any more where that came from. Needless to say I said yes, though I was lying. How soon can you deliver? they asked. That made me feel uncomfortable. Maybe there really was going to be a war, after all.

There’s always a war: it goes without saying. Every day of every year since the Invincible Sun moulded the first man out of river mud and propped him against a tree to dry, there’s been a war somewhere – little wars, silly little wars, scraps over boundaries and trade, cattle raids and state-sponsored piracy, scalp hunts, punitive expeditions, reprisals for reprisals for reprisals, pre-emptive reprisals for diplomatic snubs that haven’t even happened yet… Little wars keep me fed and clothed and busy, and being busy is good because it doesn’t leave me any time to brood on how badly I’ve screwed up my life. But big wars – the major empires and federations up on their hind legs ripping out each other’s throats – are mercifully rare: once in a generation, which is why there are still human beings, and why the entire surface of the earth isn’t covered in briars and withies. About the only thing I can say for myself is that I’ve stopped two big wars from happening, the Sashan Empire against the West; me, with my two grubby hands and my poor overworked brain, even though strictly speaking it was none of my business. I guess I don’t approve of war. Burning and burying bodies and tracking my next job of work by a trail of burned farmhouses has led me to certain conclusions. I won’t attempt to defend them, since there are all sorts of good arguments for war, devised by some of our species’ finest minds, and I wouldn’t presume to contradict them. I always come back to Saloninus’s definition of a sword – a piece of metal with a slave on both ends.

There are worse places than Holdeshar, at least a dozen of them. We chose the back bar of the Humility Exalted for the shareout. The drill is, I find the buyers and do the selling, deduct the overheads and the running costs and divide up the balance between the heads of department according to the established ratio: 10 per cent for me; 10 per cent for each department. It was nice to have something tangible to hand out for a change. For the last three jobs we’d done, they’d had to make do with fine words and promises.

I left the rest of them in the Humility and crossed the road to the Temple. The local branch of the Knights of Equity have an office there, in a small room behind the high altar. Before they were a bank, the Knights were crusaders, fighting to free the holy places from the Sashan and the Antecyrenaeans. In the end their army was slaughtered to the last man, but their fundraising arm somehow neglected to show up for the final battle, and they were left orphaned, without a reason for existing but with a very great deal of other people’s money, which they were naturally reluctant to hand back. So they reinvented themselves as a general charitable fund, although for various reasons they never got around to distributing anything. Now they’re the biggest bank in the West, slightly ahead of the Poor Sisters. They’ve tried to have me murdered more than once but I still bank with them, mostly because the only alternative would be the Sisters, who don’t like me one bit. Most of the other banks went belly-up during the financial crisis, which I caused by encouraging the Sashan to annex the fabulously wealthy island of Sirupat; I was king of Sirupat at the time (don’t ask: it’s complicated). Anyway, these days there are only two real players in the money game, both of them shadows of their former pre-crisis selves, but definitely still going and about as trustworthy as a scorpion. Which isn’t a bad thing; you can always trust a scorpion to sting you, if you provoke it.

The chief clerk of the Knights in Holdeshar is an old friend of mine. She looked up as I walked in. “Get out,” she said.

“Don’t be like that,” I said. “I’m paying in.”

“Get out,” she repeated, “before I call the guards.”

“They’re in the Humility,” I told her. “My boys are buying them drinks. Come on, Lessa, be nice. Bearing grudges doesn’t suit you.”

“Piss off and die,” said my friend, then she shrugged. “Paying in?”

“One thousand staurata, cash money.”

I wouldn’t say she actually softened, but she reached for her ledger and opened it. She’s a tall, thin woman, maybe just this side of sixty, sharp as a knife; she used to be a Sister until she had to quit the order under a bit of a cloud, something about a certain sum of money not being where it should have been. The Knights were glad to have her because of her comprehensive knowledge of where the Sisters had buried various bodies. Ending up in Holdeshar was a matter of choice rather than rotten luck or prejudice; she claims to value the simple, quiet life, which I guess I can understand.

She ruled a line across the page, then looked at me. “Go on, then,” she said. “Let’s see it.”

I had the money in a satchel under my coat, which I took off and hung on a hook behind the door. I dumped the satchel on the desk and opened it. She wrinkled her nose. “It smells,” she said.

“That’s the bag,” I explained. I’d taken it from round the neck of one of Theudebert’s adjutants. Waste not, want not.

“Why is everything to do with you always so horrible?”

I shrugged. “Beats me,” I said, and emptied the bag on to the desk. She scrabbled the coins towards her and started to count.

You don’t dare talk to Lessa while she’s counting. When she’d finished and reluctantly conceded that it was all there, I said, “You know all about politics and stuff. Is there going to be a war?”

She thought for a moment. “Not sure,” she said.

“Not sure yes or not sure no?”

“Not sure,” she said. “The Aelians want one, but the Sashan don’t. At least, they don’t want one now, not with all the problems they’ve got at home—”

“What problems?”

“But on the other hand, if they have a war now they’ll almost certainly win, but if they wait six months or a year the Aelians stand a much better chance of at least making a fight of it. Which is why I’m not sure, like I told you.”

“What problems?”

She grinned at me. “Oh, it’s all just rumour and speculation. Besides, it’s restricted information, favoured customers only. Sorry.”

“I’ve just paid in a thousand staurata.”

“Yes, but I don’t like you. Here’s your receipt. I’ll have the letter of credit sent to your branch at Auxentia. Goodbye.”

I went back to the Humility. Olybrius and Carrhasio were working up to one of their usual drunken shouting matches. Polybius had ordered the house special, which was something grey with bits in it. Gombryas was talking intensely to a fat man who was almost certainly a fellow collector; next to his elbow on the bar was an ominous looking clay pot, sealed with resin. I considered asking the landlord to bring me a pot of green-leaf tea, but decided I couldn’t be bothered. Then the man I’d arranged to meet came in, and we sat down in the quiet corner, furthest away from the door.

“Twelve thousand staurata,” he said. “Take it or leave it.”

It was a modest little war, more of a police action, in Cheuda, which is a nice enough place if you like that sort of thing: flat, which is good from the haulage point of view, but inland, which isn’t. He was representing the rebels, who were quietly confident of victory; tomorrow I’d be meeting the government, who were equally confident but likely to be more noisy. “Ten,” I said.

“I’ve got a firm offer of eleven from the Asvogel brothers.”

“Take it,” I said. “They’re a good firm, very reliable. And they can afford to work on wafer-thin margins. We can’t.”

He looked at me. I knew for a fact that Chusro Asvogel had offered him nine fifty, because Chusro told me so himself. “We prefer to work with smaller operators,” he said. “Match the Asvogels’ eleven thousand and the job’s yours.”

“I’ll match their nine fifty, with pleasure. That’s actually less than I offered you a moment ago, but that’s fine by me.”

I think he’d made up his mind that he didn’t like me. “Ten thousand staurata.”

“Nine seven-five,” I said, “and that’s my final offer.”

“You said ten a moment ago.”

“Times change.” I waited three seconds, then grinned at him. “All right, ten,” I said. “After all, that’s what the job’s actually worth to me. Does that sound fair to you?”

He sighed. “I hate bargaining,” he said.

“You’re not very good at it,” I told him. “But then, why should you be? You’re an idealist.”

That made him grin. He still didn’t like me very much. “Damn right,” he said. “When you’re building the Great Society, every compromise is a betrayal.”

“Of course it . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Saevus Corax Gets Away With Murder

K.J. Parker

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved