- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

This is the true story of Aemilius Felix Boioannes the younger, the intended and unintended consequence of his life, the bad stuff he did on purpose, and the good stuff that happened in spite of him. It is, in other words, the tale of a war to end all wards and the man responsible.

Release date: January 11, 2022

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

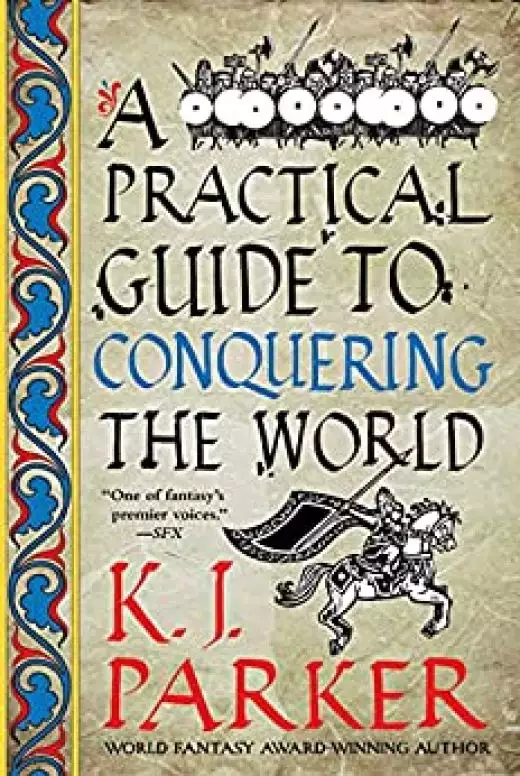

A Practical Guide to Conquering the World

K.J. Parker

It’s unfortunate that I’m the main character in this story. I can see why everybody would want to hear about what I’m going to tell you – the most amazing thing that’s happened in our lifetimes, quite possibly ever, the greatest story ever told – but me? I don’t think so. I’ve found that people quite like me at first and can put up with me for a little while after that, but it’s like they say in medicine, the dose makes the poison. Unfortunately, I come with the story. You want one, you’re going to have to put up with the other. Sorry about that.

I was dreaming about – well, that stuff – when someone shook me and I woke up.

I’m not at my best when I’ve just been dragged out of sleep. I saw three soldiers, in armour and uniform. I thought, oh God, they’ve come to arrest me, for my crime. Then I remembered, that was years ago and a very long way away, in another jurisdiction.

“You the translator?”

The sergeant spoke in barbarous Robur; in case he’d got the wrong man, presumably. “Yes, that’s me,” I replied in Echmen.

“Sorry to disturb you, sir,” he lied, “but you’re needed.”

Someone had lit the lamp. I glanced over the sergeant’s head at the window. “It’s the middle of the night,” I said. “Can’t it wait?”

“No, sir.”

The Echmen invented diplomatic immunity, so I guessed they probably wouldn’t kill me if I refused. Nor, I suspected, would they go away. “Fine,” I said. “Just give me a few minutes to get dressed, would you?”

“Sorry, sir. Our orders are, fetch you straight away.”

I felt that little twist in my stomach. “Yes, all right, but would you please wait outside?”

“Sorry, sir.”

I suppose he was used to arresting people, rather than escorting diplomats. I told myself it didn’t matter, then threw back the sheets and hopped out of bed. I thought I’d managed to keep my back to him as I hauled myself into my trousers, but a sharp intake of breath told me I hadn’t. I pulled on my shirt and turned to face him.

“What the hell happened to you?” he asked.

“Ready when you are,” I said.

The Echmen are a remarkable people, and one of the areas in which they excel is architecture. Everything they build is as big, complicated and ornate as they can possibly manage, and the Imperial palace is, quite properly, the supreme expression of Echmen aesthetics. They say that they build to impress the gods; seen from the Portals of the Sunrise, therefore, a hundred miles over our heads, the palace is a dazzling fusion of geometry and art. At ground level, it’s a rabbit warren. I know for a fact that from my garret in the lower west wing to the offices of the diplomatic service where I did most of my work was a hundred yards in a straight line, as measured by the divine dividers, but one thousand, eight hundred and forty-odd yards actual distance travelled; up stairs, along passages, down stairs, along more passages, through galleries, across cloisters, and every inch of the way decorated with the most bewilderingly lovely examples of abstract art. From my quarters to the cells underneath the Justice department is even shorter on paper and about twice as far on foot. Which gave me plenty of time to talk to my new friend the sergeant, something I really didn’t want to do.

“Are you a—?” he asked. “You know.”

Yes, I knew. But I deliberately misunderstood him. “Translator,” I said. “Yes. Who am I going to see?”

“Sorry, sir, classified.”

“I’m only asking,” I said, “because if it’s a language I don’t know, we’re all wasting our time.”

“Dejauzi, sir.”

Fine; I know Dejauzi, God only knows why. As far as anyone knows, Dejauzi speakers occupy about a third of the surface of the world, but since they’re peaceful, they don’t have anything anyone wants and they’re too fast moving, fly and vicious to be harvestable as manpower, they’re of very little interest to any of the three major governments. Actually, none of those three statements is true, but that’s what everybody believes. I learned Dejauzi when I was convalescing, because there happened to be a Dejauzi grammar lying about. It’s one of the easiest spoken languages in the world, with practically no irregular verbs.

Please note that I didn’t use the word dungeon. That would be utterly misleading. The cells, which I’d never been to before, turned out to be characteristically Echmen: graceful, symmetrical, exquisitely proportioned rooms which happened to be used for storing criminals. I think the only difference between the cell I was shown into and my own apartment was the steel door and the fact that only the ceiling was decorated, with stunningly lovely mosaic.

Inside the cell, an Echmen official, standing holding a document, and a teenage female in Echmen court dress but with the unmistakeable Dejauzi hair and makeup, sitting on a sort of stone bench. The official scowled at my sergeant. “You took your time,” he said.

“Sorry, sir.” He apologised a lot, that sergeant, though I don’t think he meant it.

“This him?”

“Sir.”

The official nodded, and the sergeant retreated, standing in front of the door.

“Sorry to drag you out of bed,” the official said. “But our man’s sick. You know Dejauzi.”

“Yes,” I said.

“Good man. Right, read this to her in Dejauzi, and then you can go.”

He handed me the document. It was written in that horrible Echmen law style they insist on using for official stuff, even though the characters are obsolete for everyday use; in effect, you have to know an additional eight thousand characters in order to make sense of it. Fortunately, I do.

I looked at the girl, who wasn’t looking at me. Then I read her the document, which was her death warrant. When I’d finished, she looked up and scowled at me.

“Ask her if she’s understood,” the official said.

“Do you understand?” I asked her.

“Fuck off.”

“She understands.”

The official nodded. “Ask her if she wishes to make any legal representations.”

So I did that. “Go fuck yourself,” she said.

“Not at this time,” I translated.

“And tell him to go fuck himself, too,” she added.

“But she reserves the right to make representations at a later date.”

The official grunted. “She’d better get a move on, then. Her head’s coming off at dawn.”

I turned back to her. “The arsehole says you’re—”

“Yes, I know. I heard him.”

“You can talk Echmen?”

“Better than you can, blueskin.”

“Do you want me to get you a lawyer?”

“Go fuck yourself.”

“Ah,” I said, “would that that were possible. I’m sorry. I hope—” I tried to remember what little I knew about Dejauzida religion. “May the Great-Great watch over you,” I said.

“Fuck the Great-Great. I’m Hus.”

I bowed politely, then turned back to the official. “Can I have a word with you outside?” I said.

He looked surprised, but nodded. The sergeant stood aside to let us pass.

“What did she do?” I asked.

“Nothing. She’s a hostage.”

Ah. Hostage for good behaviour. The daughter of some chieftain, deposited with the Echmen as a guarantee on the signing of a treaty. If the treaty is broken, the hostage is killed. “So the Hus have broken—”

“The Dejauzida.”

“She’s not Dejauzida, she’s Hus.”

He stared at me. “Are you sure?”

“That’s what she says,” I told him. “Also, she’s got a blue lifelock in her hair, and the Dejauzida lifelock is green, and the tattoos on her face are the double peacock, which is Hus.”

“You’re sure about that.”

“Yes,” I said. “No Dejauzi would have the double peacock, it’s taboo.”

“Oh, for crying out loud. You’re sure.”

“I’ve got a book you can borrow, if it’d help.”

He didn’t tell me what I could do with my book. He didn’t have to. “You’re coming with me,” he said. “We’ve got to get this sorted out.”

“Just a moment,” I said. “I’m not an expert on tribal nomads, and I don’t think my ambassador would want me getting involved in Echmen foreign affairs.”

“Maybe you should have thought about that before you opened your big mouth,” he replied, reasonably enough. “Come on, we’ve got a lot of work to do.”

It was a long night. Half a dozen officials of escalating importance had to be hauled out of their beds, explained to and induced to sign and seal things, and all of them wanted to know what the blueskin had to do with anything; with just under an hour to go, the permanent assistant deputy something-or-other pulled a sad face and said it was a terrible shame but too late to do anything about it now; whereupon one of the other officials (by now we were trailing along a small army of sleep-deprived government officers, like someone driving geese to market) pointed out that if they executed a friendly hostage, they’d all be in the shit, and it turned out that there was just enough time after all. A stay of execution was drawn up and sealed, and they needed a translator to translate it…

“You again,” she said.

“It’s all right. There’s been a mistake. You’re not going to die after all.”

She gave me a look I’ll never forget. “Are you serious?”

“They thought you were the Dejauzi hostage. I explained that you’re Hus. You are Hus, aren’t you?”

“They made a mistake.”

“Yes, but it’s all sorted out now. You are Hus, aren’t you?”

“Of course I’m bloody Hus, what do you think these are, pimples? They threw me in here and told me they were going to kill me, and it’s all a mistake. Oh for—”

“But it’s all right now,” I said. “It’s all been—”

“No, it fucking isn’t all right. I’ve been scared shitless. I’ve been sitting here all night thinking this is it, I’m going to die, and all because some idiot—”

Tears had cut deep channels in her chalk-white makeup. “I’m sorry,” I said. “But it’s all been sorted out, they’re going to let you go. But first I’ve got to read this to you, or it won’t be legal.”

“You what?”

“Shut up,” I said, “and let me read you this. Then you can go.”

She took a long, deep breath. “Get on with it, then.”

So I read her the document. “Do you understand?” I said.

“Of course I understand, what do you think I am, simple?”

“I need you to say you understand, it’s a required formality.”

“Go fuck yourself.”

“You keep saying that,” I said. “Thank you for your patience. Goodbye.”

I turned to leave. “By the way,” I told the official – the first one, who’d shared the whole wonderful experience with me, “she can understand Echmen perfectly, so you didn’t need me after all.”

He looked mildly stunned. “She didn’t say.”

“Did you ask?” I replied, and walked out of the cell.

Needless to say I got hopelessly lost trying to find my way back to my room, so my grand gesture turned round and bit me, the way grand gestures generally do. Even so.

Easy mistake to make. The Dejauzida and the Hus look identical, speak the same language and come from the same ethnic stock, but otherwise they’re completely different. The Dejauzida worship the Great-Great, the Hus are fire-worshippers, like the Echmen (though I gather it’s sort of a different fire). They hate each other like poison, as do the other twenty or so entirely distinct and separate nations that look just like the Dejauzida and speak the same language. Which is just as well for us, according to the monumental Concerning the Savages, our standard reference in the diplomatic service; because if they didn’t, and they all got along like one big happy family instead of ripping each other’s throats out at the slightest provocation, they’d be unstoppable and a real and present danger to civilisation.

There are a hell of a lot of them, that’s for sure. Nobody knows quite how many; they certainly don’t. They live in the badlands that run across the northern top end of all the three great empires, an area so vast that you can’t really get your head around it. They don’t read or write – don’t rather than can’t, please note; there’s all sorts of things we do and they don’t, which is why we tend to write them off as half-human savages. But, according to them, they don’t do them because they don’t want to, and they point to us and say, look what reading and writing and living in cities have turned you into, and we want no part of that. Well, it’s a point of view.

But the practical upshot of that is, if you want to find out anything about them, you’re entirely reliant on the testimony of outsiders, most of whom have agendas of their own. The Dejauzida don’t come and visit us if they can possibly help it, so such evidence as there is derives from diplomatic missions – invariably unsuccessful – and the few half-witted traders who thought against all the evidence that it might be possible to sell things to them. Failure doesn’t tend to make people well disposed towards those who thwarted them, and it’s easy to explain your lack of success by saying that the people who didn’t want to know are ignorant barbarians.

Some people can manage perfectly well on next to no sleep; not me. Also, like money, sleep is something I find hard to come by. By the time I eventually got back to my garret (up no less than eighty-seven winding stone stairs) I knew it was pointless going back to bed. I only had a couple of hours before I was due back on duty (the Echmen have these wonderful water clocks), and a night spent trudging up and down had left me sweaty and undiplomatically bedraggled. I plodded down the stairs to the cistern, washed off the worst of the sweat, then back up again to put on some respectable clothes and drag a comb through my hair.

Since I had a bit of time in hand, I made a detour to the clerks’ office. It’s a huge place. Once upon a time, the north wing of the palace was a monastery, staffed by a thousand monks, all praying for the souls of dead emperors. What’s now the clerks’ room used to be the monks’ dormitory, and even so the clerks are cramped for space. The Echmen invented writing, and they’re very fond of written records.

One of the thousand-odd clerks working there – only one – was a Lystragonian, and how he came to end up working for the Imperial secretariat must be a fascinating story, though I’ve never been able to drag it out of him. But he and I were the only Robur-speakers, below senior administrative level, in the whole of that vast complex, so we’d got into the habit of talking to each other.

The work ethic in the clerks’ office isn’t unbearably intense, so nobody minds if friends drop in and share a bowl of tea. My friend was happy to see me, since none of the Echmen clerks was prepared to talk to him. I told him about the amusing mix-up that nearly cost an innocent woman her life. Just to be on the safe side, I asked him could he possibly check the records and confirm that there was a Hus hostage on the books? Because if not, I’d just caused a monumental bog-up, and I’d need to explain myself to my ambassador before he heard all about it from the Echmen.

My friend pulled a face. “What’s her name?”

“You know better than that.”

“No, I don’t. And I can’t pull the file if I don’t know the name.”

I explained. The Dejauzida (including, in this instance, the Hus) have all sorts of weird taboos about names. You can’t, for example, say the name of someone who’s died; you have to use an elaborate periphrasis. Nor can you ask someone their name; nor can you tell someone yours. If you really want to know, you have to ask a member of the family (and not just any member; there’s a rigid protocol, governed by family status and the name owner’s position in the family hierarchy). Asking a princess her name would constitute an insult that could only be avenged in blood. “So I didn’t ask.”

“Fine,” said my friend. “Only, like I said, that could make it difficult.”

“Do you really think there’s more than one Hus hostage in here at the moment?”

He scowled at me. “The list isn’t cross-referenced by nationality,” he said. “No name, I can’t help you. Sorry.”

Another apology for my collection. I shrugged. “Never mind,” I said. “If I got it wrong, I’ll find out soon enough when they throw me out of the service. Of course, I’ll have to walk home, because they’ll revoke my pass for the mail, but it’s only a couple of thousand miles, and there’s plenty of wear left in these sandals.”

He rolled his eyes. “I’ll see what I can do,” he said.

“Just as well you don’t have any real work to do.”

“Drop dead, blueskin.”

I glanced up at the water clock; I was on duty. I gave him my big smile and hurried up to our department, on the fifth floor of the North tower.

Our department consisted of the ambassador, his airhead nephew, someone else’s airhead nephew and me; just as well there was never anything for us to do, or it wouldn’t have got done. Usually the ambassador didn’t put in an appearance until the middle of the afternoon, so I was a bit taken aback to find him sitting behind the desk (we only had one) with a roll of parchment in his hands.

“Sorry I’m late,” I said, and started telling him about my recent adventure. He wasn’t listening. “Read this,” he said, and handed me the parchment.

It was in Sashan; later, the ambassador told me his Sashan opposite number had given it to him to read, although strictly speaking it was classified, et cetera. It was a copy of a report from the Sashan embassy in Aelia – one of the milkface republics on the bottom edge of the Middle Sea that we never got round to conquering. It described how an army, so far unidentified, had lured the City garrison out into some forest and annihilated it, leaving the City itself completely defenceless; by the time you read this, the report said, the City will have fallen. Furthermore, the Sashan ambassador had heard reports, so far unconfirmed but from absolutely reliable sources, of an unknown but extremely powerful and well-equipped confederacy against the Robur, which was conquering and absorbing the provinces of our overseas empire at an extraordinary rate. Their declared intention was to exterminate the Robur down to the last man. If they continued their progress, said the report, it could only be a matter of weeks before the Robur empire and incidentally the Robur nation ceased to exist.

I glanced at the date on the top. The report was two months old.

I looked at the ambassador. His face was expressionless.

“It can’t be true,” I said.

He looked up at me. “When was the last time we heard from home?” he said.

“About two months. But that doesn’t mean anything.”

“I get a despatch every week,” he said. “Or I’m supposed to. I’ve been writing home every day for the last month, asking what the hell’s going on.”

“The City can’t fall,” I said.

“It can if there’s no one to defend it.”

I looked at the report, but I couldn’t make out the words; something in my eye. “It can’t be true.”

“You already said that.”

“What are we going to do?”

He laughed. “I’m claiming political asylum,” he said. “If that thing’s true, I don’t suppose I’ll get it. If I were you, I’d make myself scarce. Get as far away as you can, and stay there.” He jerked his head towards the door that connected the outer office to the cubbyhole where the nephews worked. “They’re long gone,” he said. “Don’t tell me where you’re going, I told them, that way I can’t tell anyone else.”

I stared at him. “Who are these people?”

He shrugged. “You know as much as I do,” he said. “The Sashan don’t know anything either. But they believe it. That’s their man’s idea of sportsmanship. Giving us a head start.”

I put the parchment on the desk. “Who hates us that much?”

That got me a big grin. “Everybody,” he said. “Don’t you follow current affairs?”

I ran down the stairs and along the passages to the clerks’ room. My friend the Lystragonian was at his desk, with his feet up, reading The Mirror of Earthly Passion.

“Her name,” he yawned, “is She Stamps Them Flat. And, yes, she’s Hus all right. You owe me.”

I told him what I’d just heard. He stared at me. “That’s not possible,” he said.

“You haven’t heard anything?”

He closed the book and put it down. “No, but I wouldn’t have.”

“Can you ask around?”

“Nobody talks to me, you know that. Still,” he added, looking at me, “I’ll see what I can do. Where will you be?”

Good question. Like I said, the Echmen are red hot on diplomatic immunity. Query, though; if a nation no longer exists, can it have diplomats? “The White Garden,” I said. “They like me there.”

So I went to the White Garden, though I didn’t sit at my usual table. I chose a dark corner, next to the fire. There I spent possibly the worst hour of my life. And then the soldiers came for me.

“Nothing personal,” the sergeant said, as he tied my hands behind my back. Not the same sergeant, probably just as well. “Try and hold still, we don’t want any broken bones.”

The Echmen have this wooden collar for putting round prisoners’ necks. It’s about the size of an infantry shield, with a hole in the middle for your neck, and hinges, and a padlock. It presses directly on your collarbone, and when you’re wearing it you can’t see your own feet. Wonderfully practical design, like everything the Echmen make. The sergeant wasn’t inclined to chat, for which I was grateful.

The Echmen official I eventually got to see was an elderly man with a sad face. Yes, he said, as far as anyone knew the report was true. An Echmen agent had personally seen the ruins of five Robur cities on the east coast of the Friendly Sea, which was as far west as the Echmen were prepared to go, and his sources confirmed the Sashan account in every detail. As far as the Echmen were concerned, the Robur no longer existed.

“Apart from you,” he added.

I looked at him.

“Your ambassador,” he said, “applied for political asylum, which we felt unable to grant. He took his own life. Your two colleagues in the Robur mission are also dead. They made the mistake of letting themselves be seen in the streets. I gather that news of what happened has reached the public at large, and the Robur—” He gave me a sad smile. “They were never very popular with our people at the best of times.”

I opened my mouth but nothing came out.

“I have received,” he went on, “an official application from one of the other embassies, asking for you to be transferred to their staff as a translator. If you accept the post, you will of course enjoy full diplomatic privileges. I have absolutely no idea why they would want to do this. However, I should point out that if your diplomatic status lapses, you will class as an unregistered alien, and you will no longer enjoy the protection of the law.” He paused and gave me the sort of look you really don’t want, ever. “Do you want the job or not?”

“Yes.”

He nodded to the sergeant, who came forward and unlocked that horrible collar and untied my hands. “In that case,” he said, “I suggest you report to your new masters, before they change their minds.”

“Of course,” I said. “Who—?”

He told me. One damn thing after another.

“We have this really stupid tradition,” she told me. “If someone saves your life, your soul belongs to them for nine consecutive reincarnations, unless you can save them back. Personally I think it’s bullshit, but I guess you never know.”

At least I knew her name, though it was more than my life was worth to say it. “Thank you,” I said.

“Don’t mention it. I think I’ll give you to my uncle,” she went on, “he collects rare and unique objects. Right now, from what I gather, a Robur’s about as rare and unique as it’s possible to get.”

Rather than live in a world without Robur, my ambassador had killed himself – by drinking poison, I later found out; not just any poison, real connoisseur stuff. It’s distilled from some incredibly scarce and valuable exotic flower, and you die entranced with the most gorgeous and wonderful visions, so that you feel yourself ascending bodily to heaven to the sound of harps and trumpets. On a translator’s salary, however, it’d take me ten years saving up to buy enough to kill a chicken.

“I thought you wanted me as a translator,” I said.

She nodded. “How many languages do you know?”

“I’m fluent in twelve,” I said, “and I can get by in nine more.”

Her eyes widened. “How many are there, for God’s sake?”

“The official figure is seventy-six,” I said, “but I think there’s a lot more than that.”

“And you know twenty-one of them. That’s—”

“Twenty now, of course. I don’t suppose Robur counts any more.”

That just sort of slipped out. It got me a scowl.

She was short, even by Dejauzi standards; not fat exactly, more squat and stocky, with a square face and a flat, wide nose. She had big hands, almost like a man’s. Like all Dejauzi, she’d plastered every square inch of exposed skin with brilliant white stuff (basically chalk dust and lard, with other bits and pieces in it to keep it from cracking and flaking); she wore her hair in a bun on top of her head, and it was dyed a purply blue, almost lavender. The peacocks reached from just under her eyes down to the line of her jaw; we call them tattoos but really they’re scars, carved with a flake of sharp flint around the age of twelve. The scar tissue is picked out in five different colours of greasepaint and has to be done from scratch every morning, using a basin of water as a mirror. Incidentally, there are fourteen synonyms for handsome in Dejauzi, but no word meaning pretty. She was somewhere between twelve and fifteen; I’m hopeless at women’s ages.

“We’re a bit pushed for space,” she said, “so you’ll have to sleep in here. You won’t mind that.” Statement of fact, not a query. “I know it’s not what you’re used to, but I can’t help that.”

No chair in the room; nomads sit on the ground. The floor was covered in stupendous Echmen tiles, all the colours of the rainbow and harder than granite. “It’ll be fine,” I said.

I didn’t sleep much that night. Partly because Her Majesty was in the room next door and she snored like someone killing pigs; partly because I had things on my mind. There was no window in the room, and just one little clay lamp, which soon burned out. It stank to high heaven of some kind of fat, so I didn’t mind that.

I’ll spare you a report of my mental turmoil and emotional anguish, though to be honest with you I was still in that just-been-kicked-in-the-head phase when you can’t feel anything at all. I tried to make a list of all the things I’d been planning to do when I finished my tour of duty and went home, which I wouldn’t be doing now – some bad, some good, I’ll never do that or see them again versus I won’t have to do that or see them, at any rate. I remember getting up off the floor and standing upright, shoulders back, head up, chin in, like the drill sergeant taught us; I thought, I’m still the same but from now on everything else is going to be completely different. It occurred to me that this universal-except-for-me change was bound to cause me problems; the logical thing, therefore, would be for me to change, too. How, exactly? Insufficient data for an informed decision. The ambassador had killed himself rather than face the humiliation of being someone else, and I could see a certain degree of merit in that approach. On the other hand, death isn’t like the last ship east in autumn; if you miss it, you’re stuck where you are for at least three months until the weather improves. Death is prepared to wait. It’s always there for you, like your mother.

I am by nature a relatively cheerful person. I’m inherently frivolous. I like to find the humour in everything, like a mine-owner grinding up a whole mountain to extract one ounce of pure copper. In Blemya, so they tell me, there are little tiny birds which make their living picking fibres of meat out of the yawning jaws of crocodiles, and I think I’m probably one of them; the crocodiles being Life. I’m prepared to engage with the world – at any moment my head might get bitten off by it, but that’s the risk you have to ta. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...