- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

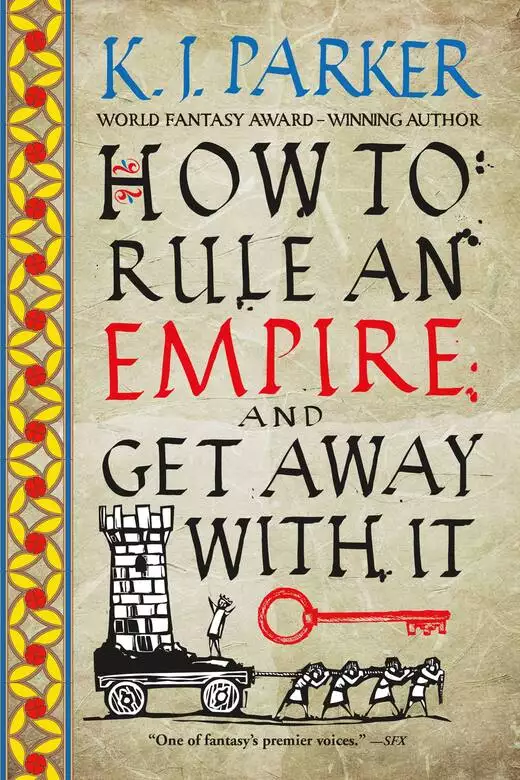

Synopsis

"Full of invention and ingenuity . . . Great fun." - SFX on Sixteen Ways to Defend a Walled City

This is the history of how the City was saved, by Notker the professional liar, written down because eventually the truth always seeps through.

The City may be under siege, but everyone still has to make a living. Take Notker, the acclaimed playwright, actor, and impresario. Nobody works harder, even when he's not working. Thankfully, it turns out that people enjoy the theater just as much when there are big rocks falling out of the sky.

But Notker is a man of many talents, and all the world is, apparently, a stage. It seems that the empire needs him -- or someone who looks a lot like him -- for a role that will call for the performance of a lifetime. At least it will guarantee fame, fortune, and immortality. If it doesn't kill him first.

In the follow up to the acclaimed Sixteen Ways to Defend a Walled City, K. J. Parker has created one of fantasy's greatest heroes, and he might even get away with it.

For more from K. J. Parker, check out:

Sixteen Ways to Defend a Walled City

The Two of Swords

The Two of Swords: Volume One

The Two of Swords Volume Two

The Two of Swords: Volume Three

The Fencer Trilogy

Colours in the Steel

The Belly of the Bow

The Proof House

The Scavenger Trilogy

Shadow

Pattern

Memory

Engineer Trilogy

Devices and Desires

Evil for Evil

The Escapement

The Company

The Folding Knife

The Hammer

Sharps

Release date: August 18, 2020

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

How to Rule an Empire and Get Away with It

K.J. Parker

It wasn’t going well. He was polite enough – he was always polite – but I was losing him.

“It’s a fantastic story,” I said. “There’s this man – Einhard would be amazing in it. It’s the part he was born for.”

A little ground regained. Einhard was hard to find parts for, and under contract. “Go on,” he said.

“There’s this man,” I went on. “He’s a nobleman by birth but fallen on hard times. He’s begging in the street.”

“That’s good,” he said cautiously. “People like that.”

“And one day he’s sitting outside the temple with his hat on the ground and his dog on a bit of string—”

“No dogs. We never work with dogs.”

“With his hat on the ground, when who should walk up but the lord high chamberlain and the grand vizier. In disguise, of course.”

“But we know it’s them.”

“Of course. And they point out that the man bears an uncanny resemblance to the king. Yes, the man says, he’s my umpteenth cousin umpteen times removed, that’s why I grew the beard, because it’s embarrassing sometimes, but what can you do? And then the grand vizier says, we need you to do a job for us, and you’ll be well paid. And it turns out that the king’s been abducted by traitors in the pay of the enemy, who want to start a war, so we need you to pretend to be him, just long enough so that—”

He raised his hand. “Let me stop you there,” he said.

Oh well, I thought.

“It’s a great story,” I said.

“I agree. It’s a fantastic story. Always has been. It was a great story a century ago in The Prisoner of Beloisa. It was even better in Carausio, and The Man in the Bronze Mask—”

“A hundred and sixteen consecutive performances,” I pointed out.

“Still a record,” he conceded. “It’s one of those stories – well, a bit like you,” he said with a smile. “Starts off really well a long time ago and just keeps on getting better and better, no matter how many times you see it, up to a point, but after a while—” He shrugged. “Best of luck with it,” he said, “but I don’t honestly think it’s for us, thanks all the same.”

“There’s a siege in it,” I told him. “And a love story.”

He hesitated. “Sieges are good,” he said. “Tell you what. Why don’t you go away and rewrite it with just the siege, and forget about the other stuff? Sieges are going down really well right now.”

Which is bizarre. Seven years into the great siege of the City; that’s real life, for crying out loud, surely the last thing you go to the theatre for is real life. But (he explained to me, when I objected) what the people want is something that looks at first sight like real life, but which actually turns out to be a fairy tale with virtue triumphant, evil utterly vanquished, a positive, uplifting message, a gutsy, kick-ass female lead and, if at all possible, unicorns. Also, I told him, what they want is something that looks new and completely original but is actually the same old story we’ve all known and loved since we were kids. Exactly, he said. But, knowing you, what you’d give them would be something genuinely new and original disguised as the same old same old; and if I were to put that on in my theatre, after a night or two the actors would start to feel terribly lonely.

So I went away. As it happens, I wrote him a positive, uplifting piece of shit about a siege where virtue triumphed, evil was vanquished and Andronica looked stunning in slinky black leather as she kicked enemy ass from one side of the proscenium to the other. It ran twenty-six nights and more or less broke even, so that was all right.

Virtue triumphant, evil utterly vanquished, a positive, uplifting message, a gutsy, kick-ass female lead and, if at all possible, unicorns. I have to confess I’m no scholar, so for all I know there may be unicorns, in Permia or somewhere like that, so maybe one component of that list does actually exist in real life. Wouldn’t like to bet the rent on it, though.

I left the theatre and walked down Fishtrap Hill into Paradise. Curious thing about this man’s city. All the really horrible bits of it have absolutely charming names. Like the Old Flower Market, which at one time must have been a place where you could buy flowers, but not in my lifetime. It burned down in that big fire about five years ago and nobody’s missed it; the inhabitants moved out and separated strictly on Theme lines – all the Blues went to Old Stairs, all the Greens to Paradise – with the result that there’s no longer anywhere in town where Blues and Greens can be found living side by side. No great loss. Theme-related murders are down about ten per cent since the Flower Market went up in smoke. It’s so much easier to tolerate your deadly enemies if you never see them from one year’s end to the next.

A respectable professional man like me has to have a reason for setting foot in Paradise; not something you’d do frivolously, or unless you absolutely had to. I walked down a couple of alleys, with that dreadful twitchy feeling you simply can’t help, like painfully sore eyes in the back of your head, then stopped at one of twenty or so identical anonymous soot-black doors, wrapped a bit of cloth round my knuckles and knocked three times. The door opened, and this woman stood there staring at me.

You wouldn’t put her on the stage. You wouldn’t dare to. Stereotypes and caricatures are all very well – our life’s blood, if the truth be told – but there’s such a thing as overdoing it. So, if you want an obnoxious old hag, you go for two or three out of the recognised iconography: wrinkles, hooked nose, wispy thin white hair like sheep’s wool caught in brambles, shrivelled hands like claws, all that. You don’t use them all, because it’s too much. Which is why you don’t get much real life on the stage. Nobody would believe it.

“Hello, Mother,” I said.

She gave me a sour look. “Oh,” she said, “it’s you.”

“Keeping well?”

“Like you give a damn.”

You don’t stand talking in doorways in Paradise. “Can I come in?” I asked.

“Why? What do you want?”

She loves me really, but I’m a great disappointment to her. “I haven’t been to see you for a while,” I said.

“Six months and four days. Not that I mind.”

“Can I come in, please?”

My mother owns her own spinning wheel, which in Paradise makes you aristocracy. She’s also the widow of a Green boss, so nobody’s stolen it yet. And that’s not all. She spins high-grade coloured yarns for the daughters of the gentry, who sit doing embroidery all day; the difference being, my mother gets paid. She’s practically blind, but she’s still very good at what she does, very quick and never any problems with the quality of the product. I once figured out that she’d spun enough silk thread to stretch from here to Atagene and back. I told her that. She has no idea where Atagene is, and couldn’t care less.

“Is it money?” she asked.

Hurtful. True, very occasionally I’ve been obliged to borrow trifling sums, but not recently. Not for at least six months. “Certainly not,” I said. “I just wanted to see you, that’s all. You’re my mother, for crying out loud.”

She sat down on that ridiculous looking low chair, put her foot on the treadle and picked up her clawful of yellow frizz, all hairy, like a fruit with mould. The wheel started to hum, as it’s done all my life. I told her what I’d been doing, or an artistic version thereof, in which virtue was triumphant and evil utterly vanquished. She pretended she couldn’t hear me over the noise of the wheel. Like I said, I’m a disappointment to her. She wanted me to be a murderer and an extortionist, like my father.

A man can take only so much of the bosom of his family, so I steered my narrative to an aesthetically pleasing conclusion, told her to take care and left.

Back up the hill, and fortunately the wind was from the sea, so by the time I emerged into Buttergate I’d left the smell of home behind me. There was a line in a play I was in once: home clings close. Which is true, but only if you let it.

From Buttergate I headed uptown. I had a paying job; private after-dinner entertainment in a fashionable house in the Crescent. Impersonations of leading figures of the day, needless to say, and as I turned the corner into that magnificent example of early Mannerist architecture I was desperately trying to remember which side my hosts were on. I hoped they were Optimates, because I can do Nicephorus and Artavasdus standing on my head (literally, for two thalers extra; goes down very well, but makes me dizzy), whereas the Populars are a bit too nondescript for easy mimicry. The house I was looking for was the third from the south (more fashionable) end, with a blue door.

I heard this whirring noise. It was just like the whir of my mother’s wheel, but it couldn’t be, could it, in context. I listened to it for maybe three heartbeats, and a shadow passed over my head and put me in the shade for just a split second, and then there was that impossibly loud thump and a big cloud of dust where the house with the blue door used to be.

There’s almost always a moment of dead silence, before all hell breaks loose. When you’ve been around as long as I have, you know what that moment is for. It’s the Invincible Sun giving you just enough time to choose: do I charge in and help and get involved, or do I discreetly turn round and walk away?

When the bombardment first started, about eighteen months ago, nobody thought about choosing. Didn’t matter who you were, when one of those colossal slabs of rock fell out of the sky and flattened something, you didn’t walk, you ran to help, do whatever you could; even me, once or twice. I remember the dust blinding me and coating the inside of my mouth with cement, and ripping off two fingernails scrabbling at a chunk of stone with a man half under it – his eyes had been squeezed out of his head by the pressure, but he was still alive. I remember my fellow citizens jostling me out of the way in the rush to get there first.

But that was eighteen months ago. Since then, we’ve settled down into a sort of a pattern. The enemy secretly builds a new super-trebuchet, capable of reaching over the walls; they haul it up to within range at first light, spend the day setting it up and loose their first ranging shot around dusk. It takes them six hours to wind it up again; only by then, our intrepid commandos have darted out through a sally port, punched through the lines, smashed up the trebuchet beyond repair and rushed back to the safety of the walls, sometimes with fewer than sixty per cent losses. So the enemy go away and build a new one, and so it goes on, pointlessly and catastrophically, like the siege; and once or twice a month, a house near the wall gets smashed (because you can’t lob a stone over the eastern end of the wall and not hit something) and that’s just life. Occasionally, there are dire personal consequences to ordinary people like me, who would have been paid good money for performing to a select audience in what’s now a mess of smashed bones and rubble. That’s real life, in this man’s town. You can see why nobody wants any more of it than they can possibly help.

I used my moment of absolute quiet sensibly. I turned round and walked back the way I came, quickly but without breaking into a run.

I’m not a writer (as you’ll agree, if you read this book). I only reach for the pen when times are hard, business is slow and nobody wants me. Then I write a part for myself – a flashy cameo, usually – and a play to go with it, and tout it round the managers until one of them is gullible enough to accept it. Because I’m better at writing for other people than for myself, my fellow actors generally like my stuff; and what the big names in the profession like, the managers like, and what the managers like, the bit players and the small fry like. In fact, everybody likes my stuff, except for me (and the public, but they don’t like anything) and as often as not we break even. Since three out of five plays in this man’s city close inside of a week and make a loss, that makes me a bankable proposition. But I’m not a writer, and I don’t want to be one.

Nor do I want to do what I mostly do for a living, which is impersonations. However, Destiny or the Invincible Sun or someone like that doesn’t really give a damn about what I want, which is why I was born and grew up looking totally, absolutely nondescript, and why I have this uncanny knack of imitating other people. Protective mimicry, possibly; or the basic actor’s urge, taken to extremes.

Not that I’ll ever be a proper actor, let alone a great one – for which I’m profoundly grateful. There’s an immutable rule that only jerks and bastards can be really fine actors. Take Psammetichus, or Deuseric, or Andronica – loathsome, arrogant, self-centred as a drill bit, and the rest. It’s easy to explain. If you spend most of your life being Psammetichus or Andronica, think how wonderful it must be to be someone else, for three hours every evening. I can imagine no greater incentive for mastering and perfecting your craft. And doing matinees.

It’s not quite like that for me. Mostly the people I impersonate are serious public figures: politicians, generals, the occasional actor, athlete or gladiator. Most of them are profoundly unpleasant people, and on balance I’d rather be me than them. Actually, there’s a remarkable paradox here. Nobody in his right mind would pay good money to see me, when I’m out of character. And nearly everybody in the City would pay very good money for a guarantee that the First Minister or the Leader of the Opposition would never been seen or heard of again. But when it’s me pretending to be the First Minister or the Leader of the Opposition – well, there aren’t exactly queues stretching down the street, but a steady trickle each night, enough to pay the rent and a very modest profit. Make of that what you can. I regard it as rather more curious than interesting.

Brick dust all down my sleeve and in my hair, and an unexpected, unwanted, free evening. I put my hand in my pocket and dredged up what at first sight looked like a promising catch of shiny silver coins; but half of them turned out to be that week’s rent, a quarter were what I owed to various friends with an unhappy knack of being able to find me, and the residue was food and a new pair of second-hand boots – not a luxury, in my line. You go and see a manager, first thing he looks at is your feet. If you’ve been walking around a lot lately, you’re probably unemployable.

I tried the other pocket, because you never know, and to my great surprise and joy I found a silk handkerchief, which I remembered picking up off the floor at a rehearsal about three weeks earlier. At the time I was in the money and had every intention of finding out whose it was and giving it back – very virtuous of me, and now my virtue was about to be rewarded. I took it to the place I usually go to, in Rose Walk, and they gave me about a quarter of what it was worth, which if you ask me was downright dishonest.

Since I was in Rose Walk, I figured I might as well go the extra fifty yards and show my face in the Sun in Splendour. I hadn’t been in there for a while, on account of not wanting to meet certain people who’d been kind and understanding when I was down on my luck, but for all its faults it’s a useful place; and I reckoned I’d be safe, since my golden-hearted creditors were both appearing in a revival of the Two Witches at the Golden Star, and therefore would be on stage at that time of day. I deliberately trod in a muddy rut in the road before I went in. Caked mud can happen to anyone, no matter how well shod, and hides cracks and splits. Attention to detail is everything.

The Sun never changes. They’ll tell you that’s because those are the exact same rushes on the floor that Huibert would have stood on when he was rehearsing the King in Dolcemara, and it would be sacrilege to replace them; likewise, that’s the very same soot on the back wall that Saloninus scraped a bit of to mix the ink with which he wrote Dream of Fair Ladies, sitting in that very corner, on the chair that wobbles a bit, next to the table that it doesn’t do to lean on too hard if you don’t want your drink all over the floor. Steeped in tradition, like the Empire itself.

The usual crowd, too; mildly surprised to see me, after so long. They knew I’d been pitching to a manager – everybody knows everything – so I didn’t have to buy my own drink. Various good friends brushed the dust off me and I made a bit of a stir explaining where it had come from, though their interest in current affairs waned considerably once they were reassured that none of the theatres had been hit. They were more interested in what I’d be writing for the Rose, with particular reference to any small but lively roles for which they might just possibly be available. I promised something nice to everyone who asked me, the way everyone always does. It’s remarkable how hope breeds in this city, like rats.

“Someone was in here looking for you,” someone told me.

Note the grammar. If the subject of the sentence had been a proper noun, nothing out of the ordinary; A, a manager with a part for me, good; B, a creditor, bad; the two sides of life’s endlessly spinning coin. But somebody meant somebody we don’t know (and in the Sun we know everybody). My wings tensed, ready to launch me into flight, like a pigeon in a tree.

“And?”

My friend grinned. “Not in the business,” she said. “Wouldn’t last five minutes if they were.”

“Ah.” I picked up the bottle and held it over her glass without actually tilting it.

“Not very good at acting,” she explained. “We’re old friends of his, haven’t seen him in ages, got the impression he hangs out here. Like hell they were.”

She’d earned an inch, which I duly poured. “In what sense?”

She frowned. “Enter the Duke and his courtiers, disguised as vagabonds. Shoes and jewellery all wrong. Not a clue.”

Unsettling. I wasn’t always an actor, believe it or not, and not everyone I’ve ever known was in the trade. “What did you tell them?”

“Haven’t seen you for ever such a long time, no idea where you might be, thought you were dead, never heard of you.” She smiled at me. “Of course, I wasn’t the only one they asked.”

“When was this?”

“About an hour ago.”

So they’d left very shortly after I arrived. Without being too obvious about it, I glanced round. Everyone who’d been in when I arrived was still there; no, I tell a lie. One face was missing. I slid the bottle – still a third full – across to her, picked up my hat and slipped out through the side door.

I walked back up Crowngate, where I was nearly trampled to death by a half-company of heavy infantry. I stepped back into a doorway and let them pass. No prizes for guessing where they were off to in such a hurry. If I was a soldier on a mission from which I wasn’t likely to come back, I don’t think I’d stomp along quite so briskly. There you go. Presumably they all reckoned they’d be the lucky ones, or one. See above, under hope.

It’s awkward keeping your head down and staying clear of people who are looking for you if you’re an actor, so I decided it was a stroke of luck that I didn’t have anything on at present. Correction: I had a play to write for the Rose, something I could do anywhere. It irked me that I wouldn’t be able to go back home but I’d still have to pay the rent, which would eat horribly into my capital. I resolved to channel my righteous indignation at the unfairness of it all into my writing, which I’m sure is what Saloninus or Aimo would have done in my shoes.

If you want to lie low in this man’s town, the closer you can get to the docks the better. Ever since the siege began, and we won back control of the sea even though the whole of the land empire had gone down the drain, there’s been an awful lot of foreigners living in and around the docks, where rents are cheap. Nobody knows them, they don’t belong to a Theme, and their money is as good as anybody else’s. They’re traders, factors, agents, sailors discharged from foreign ships, and a lot of them can’t even speak Robur; and you know what we’re like with anyone we can’t understand. I figured that if I pretended I was foreign and replied in gibberish, if anyone spoke to me I’d be left blissfully alone. I could write my play, get paid for it and stay out of sight until whoever was looking for me decided I must be dead or overseas, and all that at a price I could afford. Magic.

So I wandered around for a bit – it was dark as a bag by then – until I reckoned I’d found somewhere suitably anonymous, but where I could bear to live for a week or so, and knocked on the door. Long wait; then a panel in the door shot back and a little round bloodshot eye glared at me.

“Room,” I said, with my very best Aelian accent. I’d wrapped my scarf round my head to hide the colour of my skin.

The panel snapped shut and the door opened. The man with the eye saw what he expected to see. “Forty trachy a night,” he said. “Meals not included.”

I held out my gloved hand palm upward, with a silver quarter-thaler gleaming in the middle of it. “Room,” I said.

“Sure.” He stood aside to let me pass. “Heard you the first time.”

The skin-colour thing would be a problem, of course. As it happens, I have a genius for makeup, but all my stuff, goes without saying, was back home, and I couldn’t afford to go out and buy any more. Just as well I know how to improvise. I learned how to do a really effective whiteface with chalk, brick dust and goose fat back when I was in the chorus of The Girl with the Red Umbrella. For chalk, substitute flour, and I was able to find the whole caboodle later that night in somebody’s kitchen.

The room wasn’t bad. It had four walls, a tiny, tiny window and a door that shut if you slammed it.

My business requires me to keep fully abreast of current events. Talking of which, I’d like to protest in the strongest possible terms about the public’s – that means you – deplorable lack of loyalty and patience. Just because the minister for this or the secretary of state for that is no bloody good and couldn’t find his own arse with both hands, that’s no valid reason for turning him out of office and replacing him with someone else, almost certainly with an entirely forgettable face, a squeaky little voice that won’t carry to the back of the hall and no known mannerisms. It’s bad enough when a general gets killed leading from the front; desperate waste of my time and trouble learning him like a book, but I do understand, these things happen in war. But getting shot of a perfectly good politician just because he’s useless strikes me as downright perverse.

It wasn’t like that in the old days, of course, before the siege. High officials were appointed, not elected, and you knew you could spend the necessary time and trouble on them with a reasonable prospect of seeing a return on your investment. But when the emergency government deposed the last emperor, sidelined the House and set up direct elections – I don’t suppose they deliberately set out to make my life hell. The unfortunate consequences to me personally probably never crossed their minds; which makes it worse somehow, in my opinion.

Following the news when you’re effectively confined to a fifth-storey saltbox isn’t the easiest thing in the world, particularly if you’re playing the part of an ignorant foreigner who knows nothing about City politics and cares less. Some news, however, gets everywhere, the way sand gets under your collar on the beach.

I’d ventured out, well wrapped up and in full whiteface, to buy a loaf and a bit of cheese – which I didn’t actually need straight away, but when you’ve been banged up for three days with nobody but characters of your own creation for company, any excuse will do. The stallholders in the little market in the square opposite the dock gates are used to foreigners, though they tend not to look at them when they’re taking their money; all to the good, as far as I was concerned. Anyway, there was this fat woman, and she was talking to the woman on the next stall down, who I couldn’t see. I wasn’t really listening, but then I caught: “All lies, of course.”

“That’s not what I heard,” offstage, behind me.

“Lies,” the fat woman repeated, inadvertently spraying my cheese with spit. “They’ll say anything, the damned Opties.”

“It’s true,” asserted the voice off. “They were talking about it in the King of Beasts last night, my brother heard them. They were saying, he’s dead.”

“Bullshit,” said the fat woman.

“It’s true. Lysimachus is dead. He was at a party and a stone fell on him. Squashed flat, like a beetle.”

That got my attention. It’s a cliché, but icy fingers touched my heart. It’s only when it happens to you that you realise just what a top-flight metaphor it actually is.

Let me make one thing clear up front. I don’t care. I couldn’t give a damn. I don’t regard myself as involved.

Accordingly, the death of Lysimachus – if true – was a devastating blow to me personally, purely because imitating him accounted for something like forty per cent of my income. Sure, you can still imitate people after they’re dead, but there just isn’t the same demand. Also, in bread-and-butter burlesque work, once someone’s dead he’s only ever going to be a supporting character, not the lead, a cameo at best: and even if you stop the show every night you don’t generally get paid extra.

On the other hand – so my train of thought ran as I wandered back to my room, devastated, hardly aware of where I was or what I was doing – on the other hand, Lysimachus isn’t, sorry, wasn’t just anybody. He was the man. At the darkest hour in the City’s history – five hundred thousand bloodthirsty milkfaces camped outside the walls, the regular army all dead or scattered and the Fleet still trapped on the far side of the Ocean; with a garrison of a few hundred untrained men, he held the line against the darkness; his determination, his dauntless courage, et cetera. If he hadn’t been there, we’d all be dead. Not opinion, fact. Therefore – I consoled myself – there’s always going to be a demand for a really first-class Lysimachus impersonator, and more so now he’s dead (if he’s dead), because he’ll become the ultimate symbol of hope, and what’s the theatre about if not peddling hope to people who ought to know better? In fact – all f. . .

“It’s a fantastic story,” I said. “There’s this man – Einhard would be amazing in it. It’s the part he was born for.”

A little ground regained. Einhard was hard to find parts for, and under contract. “Go on,” he said.

“There’s this man,” I went on. “He’s a nobleman by birth but fallen on hard times. He’s begging in the street.”

“That’s good,” he said cautiously. “People like that.”

“And one day he’s sitting outside the temple with his hat on the ground and his dog on a bit of string—”

“No dogs. We never work with dogs.”

“With his hat on the ground, when who should walk up but the lord high chamberlain and the grand vizier. In disguise, of course.”

“But we know it’s them.”

“Of course. And they point out that the man bears an uncanny resemblance to the king. Yes, the man says, he’s my umpteenth cousin umpteen times removed, that’s why I grew the beard, because it’s embarrassing sometimes, but what can you do? And then the grand vizier says, we need you to do a job for us, and you’ll be well paid. And it turns out that the king’s been abducted by traitors in the pay of the enemy, who want to start a war, so we need you to pretend to be him, just long enough so that—”

He raised his hand. “Let me stop you there,” he said.

Oh well, I thought.

“It’s a great story,” I said.

“I agree. It’s a fantastic story. Always has been. It was a great story a century ago in The Prisoner of Beloisa. It was even better in Carausio, and The Man in the Bronze Mask—”

“A hundred and sixteen consecutive performances,” I pointed out.

“Still a record,” he conceded. “It’s one of those stories – well, a bit like you,” he said with a smile. “Starts off really well a long time ago and just keeps on getting better and better, no matter how many times you see it, up to a point, but after a while—” He shrugged. “Best of luck with it,” he said, “but I don’t honestly think it’s for us, thanks all the same.”

“There’s a siege in it,” I told him. “And a love story.”

He hesitated. “Sieges are good,” he said. “Tell you what. Why don’t you go away and rewrite it with just the siege, and forget about the other stuff? Sieges are going down really well right now.”

Which is bizarre. Seven years into the great siege of the City; that’s real life, for crying out loud, surely the last thing you go to the theatre for is real life. But (he explained to me, when I objected) what the people want is something that looks at first sight like real life, but which actually turns out to be a fairy tale with virtue triumphant, evil utterly vanquished, a positive, uplifting message, a gutsy, kick-ass female lead and, if at all possible, unicorns. Also, I told him, what they want is something that looks new and completely original but is actually the same old story we’ve all known and loved since we were kids. Exactly, he said. But, knowing you, what you’d give them would be something genuinely new and original disguised as the same old same old; and if I were to put that on in my theatre, after a night or two the actors would start to feel terribly lonely.

So I went away. As it happens, I wrote him a positive, uplifting piece of shit about a siege where virtue triumphed, evil was vanquished and Andronica looked stunning in slinky black leather as she kicked enemy ass from one side of the proscenium to the other. It ran twenty-six nights and more or less broke even, so that was all right.

Virtue triumphant, evil utterly vanquished, a positive, uplifting message, a gutsy, kick-ass female lead and, if at all possible, unicorns. I have to confess I’m no scholar, so for all I know there may be unicorns, in Permia or somewhere like that, so maybe one component of that list does actually exist in real life. Wouldn’t like to bet the rent on it, though.

I left the theatre and walked down Fishtrap Hill into Paradise. Curious thing about this man’s city. All the really horrible bits of it have absolutely charming names. Like the Old Flower Market, which at one time must have been a place where you could buy flowers, but not in my lifetime. It burned down in that big fire about five years ago and nobody’s missed it; the inhabitants moved out and separated strictly on Theme lines – all the Blues went to Old Stairs, all the Greens to Paradise – with the result that there’s no longer anywhere in town where Blues and Greens can be found living side by side. No great loss. Theme-related murders are down about ten per cent since the Flower Market went up in smoke. It’s so much easier to tolerate your deadly enemies if you never see them from one year’s end to the next.

A respectable professional man like me has to have a reason for setting foot in Paradise; not something you’d do frivolously, or unless you absolutely had to. I walked down a couple of alleys, with that dreadful twitchy feeling you simply can’t help, like painfully sore eyes in the back of your head, then stopped at one of twenty or so identical anonymous soot-black doors, wrapped a bit of cloth round my knuckles and knocked three times. The door opened, and this woman stood there staring at me.

You wouldn’t put her on the stage. You wouldn’t dare to. Stereotypes and caricatures are all very well – our life’s blood, if the truth be told – but there’s such a thing as overdoing it. So, if you want an obnoxious old hag, you go for two or three out of the recognised iconography: wrinkles, hooked nose, wispy thin white hair like sheep’s wool caught in brambles, shrivelled hands like claws, all that. You don’t use them all, because it’s too much. Which is why you don’t get much real life on the stage. Nobody would believe it.

“Hello, Mother,” I said.

She gave me a sour look. “Oh,” she said, “it’s you.”

“Keeping well?”

“Like you give a damn.”

You don’t stand talking in doorways in Paradise. “Can I come in?” I asked.

“Why? What do you want?”

She loves me really, but I’m a great disappointment to her. “I haven’t been to see you for a while,” I said.

“Six months and four days. Not that I mind.”

“Can I come in, please?”

My mother owns her own spinning wheel, which in Paradise makes you aristocracy. She’s also the widow of a Green boss, so nobody’s stolen it yet. And that’s not all. She spins high-grade coloured yarns for the daughters of the gentry, who sit doing embroidery all day; the difference being, my mother gets paid. She’s practically blind, but she’s still very good at what she does, very quick and never any problems with the quality of the product. I once figured out that she’d spun enough silk thread to stretch from here to Atagene and back. I told her that. She has no idea where Atagene is, and couldn’t care less.

“Is it money?” she asked.

Hurtful. True, very occasionally I’ve been obliged to borrow trifling sums, but not recently. Not for at least six months. “Certainly not,” I said. “I just wanted to see you, that’s all. You’re my mother, for crying out loud.”

She sat down on that ridiculous looking low chair, put her foot on the treadle and picked up her clawful of yellow frizz, all hairy, like a fruit with mould. The wheel started to hum, as it’s done all my life. I told her what I’d been doing, or an artistic version thereof, in which virtue was triumphant and evil utterly vanquished. She pretended she couldn’t hear me over the noise of the wheel. Like I said, I’m a disappointment to her. She wanted me to be a murderer and an extortionist, like my father.

A man can take only so much of the bosom of his family, so I steered my narrative to an aesthetically pleasing conclusion, told her to take care and left.

Back up the hill, and fortunately the wind was from the sea, so by the time I emerged into Buttergate I’d left the smell of home behind me. There was a line in a play I was in once: home clings close. Which is true, but only if you let it.

From Buttergate I headed uptown. I had a paying job; private after-dinner entertainment in a fashionable house in the Crescent. Impersonations of leading figures of the day, needless to say, and as I turned the corner into that magnificent example of early Mannerist architecture I was desperately trying to remember which side my hosts were on. I hoped they were Optimates, because I can do Nicephorus and Artavasdus standing on my head (literally, for two thalers extra; goes down very well, but makes me dizzy), whereas the Populars are a bit too nondescript for easy mimicry. The house I was looking for was the third from the south (more fashionable) end, with a blue door.

I heard this whirring noise. It was just like the whir of my mother’s wheel, but it couldn’t be, could it, in context. I listened to it for maybe three heartbeats, and a shadow passed over my head and put me in the shade for just a split second, and then there was that impossibly loud thump and a big cloud of dust where the house with the blue door used to be.

There’s almost always a moment of dead silence, before all hell breaks loose. When you’ve been around as long as I have, you know what that moment is for. It’s the Invincible Sun giving you just enough time to choose: do I charge in and help and get involved, or do I discreetly turn round and walk away?

When the bombardment first started, about eighteen months ago, nobody thought about choosing. Didn’t matter who you were, when one of those colossal slabs of rock fell out of the sky and flattened something, you didn’t walk, you ran to help, do whatever you could; even me, once or twice. I remember the dust blinding me and coating the inside of my mouth with cement, and ripping off two fingernails scrabbling at a chunk of stone with a man half under it – his eyes had been squeezed out of his head by the pressure, but he was still alive. I remember my fellow citizens jostling me out of the way in the rush to get there first.

But that was eighteen months ago. Since then, we’ve settled down into a sort of a pattern. The enemy secretly builds a new super-trebuchet, capable of reaching over the walls; they haul it up to within range at first light, spend the day setting it up and loose their first ranging shot around dusk. It takes them six hours to wind it up again; only by then, our intrepid commandos have darted out through a sally port, punched through the lines, smashed up the trebuchet beyond repair and rushed back to the safety of the walls, sometimes with fewer than sixty per cent losses. So the enemy go away and build a new one, and so it goes on, pointlessly and catastrophically, like the siege; and once or twice a month, a house near the wall gets smashed (because you can’t lob a stone over the eastern end of the wall and not hit something) and that’s just life. Occasionally, there are dire personal consequences to ordinary people like me, who would have been paid good money for performing to a select audience in what’s now a mess of smashed bones and rubble. That’s real life, in this man’s town. You can see why nobody wants any more of it than they can possibly help.

I used my moment of absolute quiet sensibly. I turned round and walked back the way I came, quickly but without breaking into a run.

I’m not a writer (as you’ll agree, if you read this book). I only reach for the pen when times are hard, business is slow and nobody wants me. Then I write a part for myself – a flashy cameo, usually – and a play to go with it, and tout it round the managers until one of them is gullible enough to accept it. Because I’m better at writing for other people than for myself, my fellow actors generally like my stuff; and what the big names in the profession like, the managers like, and what the managers like, the bit players and the small fry like. In fact, everybody likes my stuff, except for me (and the public, but they don’t like anything) and as often as not we break even. Since three out of five plays in this man’s city close inside of a week and make a loss, that makes me a bankable proposition. But I’m not a writer, and I don’t want to be one.

Nor do I want to do what I mostly do for a living, which is impersonations. However, Destiny or the Invincible Sun or someone like that doesn’t really give a damn about what I want, which is why I was born and grew up looking totally, absolutely nondescript, and why I have this uncanny knack of imitating other people. Protective mimicry, possibly; or the basic actor’s urge, taken to extremes.

Not that I’ll ever be a proper actor, let alone a great one – for which I’m profoundly grateful. There’s an immutable rule that only jerks and bastards can be really fine actors. Take Psammetichus, or Deuseric, or Andronica – loathsome, arrogant, self-centred as a drill bit, and the rest. It’s easy to explain. If you spend most of your life being Psammetichus or Andronica, think how wonderful it must be to be someone else, for three hours every evening. I can imagine no greater incentive for mastering and perfecting your craft. And doing matinees.

It’s not quite like that for me. Mostly the people I impersonate are serious public figures: politicians, generals, the occasional actor, athlete or gladiator. Most of them are profoundly unpleasant people, and on balance I’d rather be me than them. Actually, there’s a remarkable paradox here. Nobody in his right mind would pay good money to see me, when I’m out of character. And nearly everybody in the City would pay very good money for a guarantee that the First Minister or the Leader of the Opposition would never been seen or heard of again. But when it’s me pretending to be the First Minister or the Leader of the Opposition – well, there aren’t exactly queues stretching down the street, but a steady trickle each night, enough to pay the rent and a very modest profit. Make of that what you can. I regard it as rather more curious than interesting.

Brick dust all down my sleeve and in my hair, and an unexpected, unwanted, free evening. I put my hand in my pocket and dredged up what at first sight looked like a promising catch of shiny silver coins; but half of them turned out to be that week’s rent, a quarter were what I owed to various friends with an unhappy knack of being able to find me, and the residue was food and a new pair of second-hand boots – not a luxury, in my line. You go and see a manager, first thing he looks at is your feet. If you’ve been walking around a lot lately, you’re probably unemployable.

I tried the other pocket, because you never know, and to my great surprise and joy I found a silk handkerchief, which I remembered picking up off the floor at a rehearsal about three weeks earlier. At the time I was in the money and had every intention of finding out whose it was and giving it back – very virtuous of me, and now my virtue was about to be rewarded. I took it to the place I usually go to, in Rose Walk, and they gave me about a quarter of what it was worth, which if you ask me was downright dishonest.

Since I was in Rose Walk, I figured I might as well go the extra fifty yards and show my face in the Sun in Splendour. I hadn’t been in there for a while, on account of not wanting to meet certain people who’d been kind and understanding when I was down on my luck, but for all its faults it’s a useful place; and I reckoned I’d be safe, since my golden-hearted creditors were both appearing in a revival of the Two Witches at the Golden Star, and therefore would be on stage at that time of day. I deliberately trod in a muddy rut in the road before I went in. Caked mud can happen to anyone, no matter how well shod, and hides cracks and splits. Attention to detail is everything.

The Sun never changes. They’ll tell you that’s because those are the exact same rushes on the floor that Huibert would have stood on when he was rehearsing the King in Dolcemara, and it would be sacrilege to replace them; likewise, that’s the very same soot on the back wall that Saloninus scraped a bit of to mix the ink with which he wrote Dream of Fair Ladies, sitting in that very corner, on the chair that wobbles a bit, next to the table that it doesn’t do to lean on too hard if you don’t want your drink all over the floor. Steeped in tradition, like the Empire itself.

The usual crowd, too; mildly surprised to see me, after so long. They knew I’d been pitching to a manager – everybody knows everything – so I didn’t have to buy my own drink. Various good friends brushed the dust off me and I made a bit of a stir explaining where it had come from, though their interest in current affairs waned considerably once they were reassured that none of the theatres had been hit. They were more interested in what I’d be writing for the Rose, with particular reference to any small but lively roles for which they might just possibly be available. I promised something nice to everyone who asked me, the way everyone always does. It’s remarkable how hope breeds in this city, like rats.

“Someone was in here looking for you,” someone told me.

Note the grammar. If the subject of the sentence had been a proper noun, nothing out of the ordinary; A, a manager with a part for me, good; B, a creditor, bad; the two sides of life’s endlessly spinning coin. But somebody meant somebody we don’t know (and in the Sun we know everybody). My wings tensed, ready to launch me into flight, like a pigeon in a tree.

“And?”

My friend grinned. “Not in the business,” she said. “Wouldn’t last five minutes if they were.”

“Ah.” I picked up the bottle and held it over her glass without actually tilting it.

“Not very good at acting,” she explained. “We’re old friends of his, haven’t seen him in ages, got the impression he hangs out here. Like hell they were.”

She’d earned an inch, which I duly poured. “In what sense?”

She frowned. “Enter the Duke and his courtiers, disguised as vagabonds. Shoes and jewellery all wrong. Not a clue.”

Unsettling. I wasn’t always an actor, believe it or not, and not everyone I’ve ever known was in the trade. “What did you tell them?”

“Haven’t seen you for ever such a long time, no idea where you might be, thought you were dead, never heard of you.” She smiled at me. “Of course, I wasn’t the only one they asked.”

“When was this?”

“About an hour ago.”

So they’d left very shortly after I arrived. Without being too obvious about it, I glanced round. Everyone who’d been in when I arrived was still there; no, I tell a lie. One face was missing. I slid the bottle – still a third full – across to her, picked up my hat and slipped out through the side door.

I walked back up Crowngate, where I was nearly trampled to death by a half-company of heavy infantry. I stepped back into a doorway and let them pass. No prizes for guessing where they were off to in such a hurry. If I was a soldier on a mission from which I wasn’t likely to come back, I don’t think I’d stomp along quite so briskly. There you go. Presumably they all reckoned they’d be the lucky ones, or one. See above, under hope.

It’s awkward keeping your head down and staying clear of people who are looking for you if you’re an actor, so I decided it was a stroke of luck that I didn’t have anything on at present. Correction: I had a play to write for the Rose, something I could do anywhere. It irked me that I wouldn’t be able to go back home but I’d still have to pay the rent, which would eat horribly into my capital. I resolved to channel my righteous indignation at the unfairness of it all into my writing, which I’m sure is what Saloninus or Aimo would have done in my shoes.

If you want to lie low in this man’s town, the closer you can get to the docks the better. Ever since the siege began, and we won back control of the sea even though the whole of the land empire had gone down the drain, there’s been an awful lot of foreigners living in and around the docks, where rents are cheap. Nobody knows them, they don’t belong to a Theme, and their money is as good as anybody else’s. They’re traders, factors, agents, sailors discharged from foreign ships, and a lot of them can’t even speak Robur; and you know what we’re like with anyone we can’t understand. I figured that if I pretended I was foreign and replied in gibberish, if anyone spoke to me I’d be left blissfully alone. I could write my play, get paid for it and stay out of sight until whoever was looking for me decided I must be dead or overseas, and all that at a price I could afford. Magic.

So I wandered around for a bit – it was dark as a bag by then – until I reckoned I’d found somewhere suitably anonymous, but where I could bear to live for a week or so, and knocked on the door. Long wait; then a panel in the door shot back and a little round bloodshot eye glared at me.

“Room,” I said, with my very best Aelian accent. I’d wrapped my scarf round my head to hide the colour of my skin.

The panel snapped shut and the door opened. The man with the eye saw what he expected to see. “Forty trachy a night,” he said. “Meals not included.”

I held out my gloved hand palm upward, with a silver quarter-thaler gleaming in the middle of it. “Room,” I said.

“Sure.” He stood aside to let me pass. “Heard you the first time.”

The skin-colour thing would be a problem, of course. As it happens, I have a genius for makeup, but all my stuff, goes without saying, was back home, and I couldn’t afford to go out and buy any more. Just as well I know how to improvise. I learned how to do a really effective whiteface with chalk, brick dust and goose fat back when I was in the chorus of The Girl with the Red Umbrella. For chalk, substitute flour, and I was able to find the whole caboodle later that night in somebody’s kitchen.

The room wasn’t bad. It had four walls, a tiny, tiny window and a door that shut if you slammed it.

My business requires me to keep fully abreast of current events. Talking of which, I’d like to protest in the strongest possible terms about the public’s – that means you – deplorable lack of loyalty and patience. Just because the minister for this or the secretary of state for that is no bloody good and couldn’t find his own arse with both hands, that’s no valid reason for turning him out of office and replacing him with someone else, almost certainly with an entirely forgettable face, a squeaky little voice that won’t carry to the back of the hall and no known mannerisms. It’s bad enough when a general gets killed leading from the front; desperate waste of my time and trouble learning him like a book, but I do understand, these things happen in war. But getting shot of a perfectly good politician just because he’s useless strikes me as downright perverse.

It wasn’t like that in the old days, of course, before the siege. High officials were appointed, not elected, and you knew you could spend the necessary time and trouble on them with a reasonable prospect of seeing a return on your investment. But when the emergency government deposed the last emperor, sidelined the House and set up direct elections – I don’t suppose they deliberately set out to make my life hell. The unfortunate consequences to me personally probably never crossed their minds; which makes it worse somehow, in my opinion.

Following the news when you’re effectively confined to a fifth-storey saltbox isn’t the easiest thing in the world, particularly if you’re playing the part of an ignorant foreigner who knows nothing about City politics and cares less. Some news, however, gets everywhere, the way sand gets under your collar on the beach.

I’d ventured out, well wrapped up and in full whiteface, to buy a loaf and a bit of cheese – which I didn’t actually need straight away, but when you’ve been banged up for three days with nobody but characters of your own creation for company, any excuse will do. The stallholders in the little market in the square opposite the dock gates are used to foreigners, though they tend not to look at them when they’re taking their money; all to the good, as far as I was concerned. Anyway, there was this fat woman, and she was talking to the woman on the next stall down, who I couldn’t see. I wasn’t really listening, but then I caught: “All lies, of course.”

“That’s not what I heard,” offstage, behind me.

“Lies,” the fat woman repeated, inadvertently spraying my cheese with spit. “They’ll say anything, the damned Opties.”

“It’s true,” asserted the voice off. “They were talking about it in the King of Beasts last night, my brother heard them. They were saying, he’s dead.”

“Bullshit,” said the fat woman.

“It’s true. Lysimachus is dead. He was at a party and a stone fell on him. Squashed flat, like a beetle.”

That got my attention. It’s a cliché, but icy fingers touched my heart. It’s only when it happens to you that you realise just what a top-flight metaphor it actually is.

Let me make one thing clear up front. I don’t care. I couldn’t give a damn. I don’t regard myself as involved.

Accordingly, the death of Lysimachus – if true – was a devastating blow to me personally, purely because imitating him accounted for something like forty per cent of my income. Sure, you can still imitate people after they’re dead, but there just isn’t the same demand. Also, in bread-and-butter burlesque work, once someone’s dead he’s only ever going to be a supporting character, not the lead, a cameo at best: and even if you stop the show every night you don’t generally get paid extra.

On the other hand – so my train of thought ran as I wandered back to my room, devastated, hardly aware of where I was or what I was doing – on the other hand, Lysimachus isn’t, sorry, wasn’t just anybody. He was the man. At the darkest hour in the City’s history – five hundred thousand bloodthirsty milkfaces camped outside the walls, the regular army all dead or scattered and the Fleet still trapped on the far side of the Ocean; with a garrison of a few hundred untrained men, he held the line against the darkness; his determination, his dauntless courage, et cetera. If he hadn’t been there, we’d all be dead. Not opinion, fact. Therefore – I consoled myself – there’s always going to be a demand for a really first-class Lysimachus impersonator, and more so now he’s dead (if he’s dead), because he’ll become the ultimate symbol of hope, and what’s the theatre about if not peddling hope to people who ought to know better? In fact – all f. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

How to Rule an Empire and Get Away with It

K.J. Parker

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved