- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

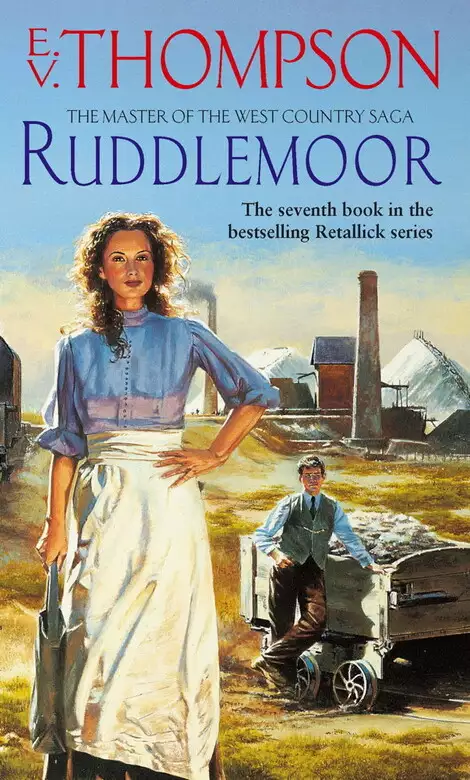

Synopsis

Josh Retallick and his wife Miriam take on an exciting new challenge as owners of Ruddlemoor china clay works on the outskirts of St Austell. But a family tragedy forces Josh to leave almost immediately. When he returns he knows that his youngest grandson will one day follow him. So it is that several years later Ben Retallick journeys to Cornwall. His arrival rocks the local community - labourers are wary of this strapping young lad; rival clay owners see him as an unwelcome threat; and Ben's charm sets many a girl's heart aflutter. Deirdre Tresillian, a member of the landed gentry, takes advantage of Ben's naivety; Jo, a poverty-stricken young widow, brings out his protective instincts; Tess considers any man fair game; but it is Lily, Ben's distant cousin, who loves him the most. But what would the future owner of Ruddlemoor see in a humble maid like Lily? As Ruddlemoor enters troubled times, Ben proves that in business no challenge is too great; and in love only one girl can win his heart.

Release date: July 5, 2012

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 688

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Ruddlemoor

E.V. Thompson

up his pen. Miriam, his wife, was seated on his left and mine captain Malachi Sprittle on his right. Standing about them unsmiling

was the whole of their workforce, men, women and children.

Slowly and deliberately, Josh made an entry in the large leatherbound ledger on the table before him. When it was done he

picked up a rocker-style blotter and carefully dried the ink on the entry.

Not until he was fully satisfied did he put down the blotter and slowly close the ledger. The action caused a brief stir among

the watching men and women, but still no one said anything.

Thin leather laces were glued into the binding of the ledger. Tying them together in a neat bow, Josh sat back in his chair.

Only Miriam knew the depths of anguish he was feeling at this moment. In the darkness of the bedroom of their moorland home,

Josh had spent much of the previous night agonising about the decision that he was having to take.

Visibly moved, it was some moments before he could gather enough composure to speak, and Miriam reached out a hand to squeeze

his arm in an affectionate and supportive gesture.

Josh was in his late sixties now. Tall and upright, he boasted that he was as fit as most men half his age, but at this moment

he looked gaunt and strained. Resting a hand on the closed ledger, he looked slowly from face to face of those who stood about

him.

When he finally spoke, his voice was charged with emotion.

‘You’ve just witnessed the last entry in the ledger of the Sharptor mine. All debts are settled and everyone who works for

me has been paid off. The working life of Sharptor has finally come to an end.’

His words released a sudden babble of sound. It was as though no one had dared speak whilst the last rites were being administered

to the already deceased mine.

‘It’s a sad day, Josh – especially for you.’ The sentiment was expressed hesitantly by Malachi Sprittle, whom fate had decreed

would be the last captain of the Sharptor mine.

‘A day I hoped would never come to pass,’ agreed Josh, aware of Miriam’s hand on his arm and trying his best to control the

emotion he felt. ‘But we’ve kept going for longer than most. No one knows better than you that the mine should have shut down

years ago. We’ve been working at a loss for the past five years – and struggling to break even for many years before that.’

As those who had lost their livelihood on the mine began to drift away with undisguised reluctance, Josh looked out across

the wide Tamar Valley. Beginning at the edge of the slope below Sharptor, it stretched for as far as a man could see, all the way from Bodmin Moor to its much larger sister moor, Dartmoor, no more than a faint upland

mass on the far horizon.

Born on Sharptor, Josh’s earliest memories were of the view before him now. He had no need to count the chimneys of the engine-houses

that stood tall in the near-distance, rising above everything about them.

There were eleven in number. For very many years he had stood here on this spot, watching the smoke belching from those same

chimneys. Weather vanes for the capricious wind, they had also been barometers of the fortunes of Cornwall’s equally unpredictable

mining industry.

Smoke rising from an engine-house chimney signalled a return on the investments made by the mining adventurers. It also indicated

that money was going into some five thousand homes, providing food, clothing and warmth for the occupants and dignity for

the man of the house.

Today there was no smoke. Washed clean by the previous night’s rain, the sky between chimney and heaven was unblemished by

God or man.

Josh surveyed the scene with great sadness. During his lifetime he had witnessed both the heyday and the passing of an industry

that had been an integral part of Cornwall for some centuries.

‘Do you still intend staying on at the house here?’

Miriam put the question to Malachi, who had stood up and was standing silently beside Josh.

‘If that’s all right with you and Josh? Maggie and I are too old to move on now, Miriam. Our needs are small and I’ve got

a bit of money put by. What with the garden and a pig or two, we’ll manage comfortably enough.’

‘You don’t need to ask me if it will be all right, Malachi,’ replied Josh, without shifting his gaze from the panoramic view before him.

He would no doubt be leaving Bodmin Moor soon and knew this was what he would miss most of all. It was something he did not

want to think about too deeply.

He and Miriam had already spent many hours debating the matter. They had both accumulated sufficient years and money to retire

if they so wished. However, Josh had made the decision to move to China clay country and continue to work. That way they could

guarantee employment to those who had loyally served them for years and who would otherwise be left with little prospect of

ever working again. The Sharptor mine had been one of only a handful still operating on Bodmin Moor.

Returning his thoughts to Malachi, Josh said, ‘I’ve told you, the house is yours. It’s a return for all the years of service

you’ve given to the Sharptor mine. You’ll not need to want for anything, either. Copper mining might have come to an end,

but I have money coming in from my China clay shares. I’ve never regretted buying them. If I hadn’t, the mine would have closed

nigh on twenty years ago. As it is, clay will provide work for any of the Sharptor men who are prepared to move. For their

families too.’

‘The women will push their menfolk into moving, Josh,’ said Miriam. ‘They’ll need to have money coming into the household

– though they’ll be as sad as anyone else to move from here.’

‘I’m not so sure all the men will be able to make the change.’ Malachi shook his head doubtfully. ‘You can’t tell a mole it’s

got to change its habits and live above ground like a mouse.’

‘They’ve either got to change or leave Cornwall – leave England. Mining has always been my life and that of my father before me, but it’s all but finished, Malachi, as all

thinking men know.’

‘It’s not logic but emotion involved here, Josh. For most of us mining comes as natural as breathing, or eating. It’s difficult

for men to imagine life without a mine on their doorstep.’

Josh made a gesture of hopelessness. ‘We’ve all got to learn that times have changed. Future generations are going to grow

up without the clatter of a stamp in their ears. They’ll never have heard the earth-shaking thud of a beam-engine. It’s sad,

Malachi, but that’s the truth of the matter.’

As silence fell between the two men, Miriam looked up sharply. There was a sudden commotion among the crowd moving down the

slope towards Henwood village. Suddenly men and women began turning back to the mine, following a young man who came up the

hill at an unsteady run.

When he picked out Josh, he headed towards him, scrambling to his feet quickly when he slipped on a patch of mud.

‘Mr Retallick …’ standing splay-legged before Josh, the man gasped out his words, fighting for breath, ‘the Notter mine …

engine-house has collapsed … The beam’s slid down the main shaft … carried tackle and ladders away. Men too. The cap’n says

we haven’t enough men above ground to set to and bring ’em out. We need help …’

A few moments before, Josh and the men with him had been feeling sorry for themselves because of the closure of the Sharptor

mine. All such feelings disappeared immediately they heard the distraught man’s words.

Josh knew the Notter mine well. Situated on a hill on the far side of Henwood village, it had experienced a decline similar to that which had hit Sharptor. However, unlike Sharptor,

the mine had attempted to maintain production by economising on such things as maintenance. Their engineer had left the year

before. Recently, Josh had heard rumours that the engine was ‘running rough’ and shaking the engine-house apart.

There would undoubtedly be miners hurt in the Notter mine disaster. Men whose need for work had forced them to keep to themselves

any misgivings they might have had about safety on the mine.

‘Malachi, take all the surface men to Notter with you right away. Seth –’ he turned to his below-ground captain, ‘– collect

as many shift-men as you can find. Miriam, can you and the women find bandages and anything else that might be used for injured

men? Sam, bring a couple of wagons with tackle for lifting – spare horses too, for winching up. The Notter mine’s been running

down for a long time, they’ll have little rescue equipment to hand.’

Miners who had been listening to Josh’s instructions were running to various parts of Sharptor as he talked. They shouted

to others still returning. Men and women ran to help, according to their capabilities.

Some headed off immediately for the Notter mine. Others, older or less able, helped to load the wagons that would carry rescue

equipment to the scene of the accident.

Every man, woman and child worked to the limit of his or her strength. All had known mine tragedies in the area before and

each had suffered some degree of loss.

Death was a notorious stealer of husbands and fathers. He stood constantly by the shoulder of a miner.

Suddenly, the troubles of the Sharptor mine were brought into perspective and set to one side. This was the dark side of mining that would never need to be experienced again

by the Sharptor community.

When Josh arrived at the Notter mine he was presented with a scene of chaos. A large part of the stone wall of the engine-house

had collapsed. Rubble and broken beams from the house were strewn around the head of the shaft, immediately beneath the spot

where the giant iron bob of the beam-engine had been. Spars from the pithead structure protruded from the shaft entrance.

Many more would have fallen into the shaft.

Men were milling amidst the wreckage about the gaping shaft, but none appeared to be doing anything useful. Josh looked for

injured men around the engine-house. To his surprise there were none to be seen.

When he met up with Malachi Sprittle, the ageing Sharptor mine captain, Josh learned the reason.

‘We’re having problems getting to the men underground, Josh. The bob carried the ladders away for at least ten fathoms when

it fell. It’s jammed, with the rest of the pithead gear, about forty or fifty fathoms down the shaft. I winched a man down

there as soon as I arrived. He’s just come to the surface and says it’s a dangerous mess. We don’t know what’s holding the bob. It could break free again at any moment.’

‘What about the adit? Haven’t any of the underground men come out that way?’

The adit was a drainage tunnel, dug through the hillside to the main workings. It should have provided an escape route for

any men trapped in the mine.

‘This isn’t the Sharptor, Josh. Things have been let go. All the lower levels are flooded because the adit tunnel collapsed

and no one did anything about it.’

‘How many men are underground?’

Malachi shook his head. ‘No one knows for certain. Twelve at least. Possibly twice that number.’

‘We’ve got to do something to bring them out. Where’s the man who was winched down the shaft?’

A small crowd of Sharptor miners had gathered around them. Aware there were men below ground to be rescued, they looked to

Josh and the Sharptor mine captain to give them orders. One of their number stepped forward now.

‘I went down, Mr Retallick.’

Josh knew the man. He was an experienced miner. Any report he gave would be accurate. He nodded his head in silent acknowledgement

of the man’s courage. A tangle of broken and dangerous pitwork still hung over the shaft opening. It could have fallen at

any time.

‘The adit’s blocked. Our only chance of reaching the men underground is to clear the shaft. What’s it like down there?’

The Sharptor man shook his head doubtfully. ‘It’s a mess, Mr Retallick. The end of the bob’s poking up through a whole jumble

of timbers, ladders and the like. I don’t know what the other end’s resting on, but there’s a lot of weight in a bob. It could

go at any time – and there’s nigh a hundred fathoms of shaft down below the blockage.’

‘There’s no other way in. We can probably blast enough of the tangle away to get the men up, but they need to be warned first,

otherwise some of them are likely to be trying to climb the shaft. We also need to place the charge beneath the wreckage. Do you think it’s at all possible for anyone to get through?’

The miner shook his head, but with less certainty this time. ‘There are spaces among the wreckage, but they’re very small. To my mind the only thing likely to get through is one of they monkeys

I’ve heard tell of.’

‘So it isn’t a solid mass blocking the shaft?’ Josh clutched at the only faint glimmer of hope the man’s report had given

him.

‘Well, I didn’t stand on it for fear it’d give way under me, but I saw a gap or two. I didn’t go close enough to see any more

than that.’

‘You can’t ask a man to risk his life among the mess down there, Josh. It’s likely to collapse at any time.’

‘Can you think of any other way, Malachi?’

The Sharptor mine captain could not, but shook his head dubiously.

At that moment a young man, stoop-shouldered and thin to the point of emaciation, stepped from the crowd which had been listening

to the conversation of the two men.

‘Is there something I can do down there, Josh?’

The young man was Darley Shovell, a great-nephew of Josh’s. His home was in St Austell, some twenty-five miles away, in clay

country. With his sister, Lily, he had been sent to stay with Josh and Miriam on Bodmin Moor for a few days. His mother, Lottie,

hoped the moorland air might improve his ailing health.

‘You, Darley?’ Josh looked at the slight young man and tried to keep the pity he felt for him from showing. ‘It will take

a team of men and lifting gear to make an impression on the tangle down there without risking more lives.’

‘Uncle Josh is right.’ A slim, bright-eyed young girl of about nine stepped forward and took Darley’s hand. ‘It’s dangerous

in the shaft. Ma would be angry if she knew you were even thinking about going down there.’

‘I’m not talking of trying to shift anything, but if there’s room to squeeze through to the men who’re trapped, I reckon I

could manage better than anyone else.’

‘You were sent to the moor to improve your health, Darley. Your ma …’

‘Why do you and Lily keep bringing Ma into this? She’s not here to say yes or no. Besides, one of the first stories I can

remember being told was how, when Ma was a young girl, she was saved from a fire in the Sharptor mine by Pa. He squeezed through

a narrow space in the roof to do it, I believe? The story’s repeated every time more than two of the family get together.

I would hope she’d understand, Josh. Especially as there are miners down there, some of them injured no doubt. They’ll be

relying upon someone up here to do something to save them.’

It should not have taken Josh by surprise that, although Darley’s body appeared weak, his resolve was not. Darley’s mother,

Lottie, was one of the strongest-minded women that Josh knew. His father too was a strong-willed man. He had organised a powerful

Benevolent Association of clayworkers in the St Austell area of Cornwall, despite considerable opposition from the works’

owners.

‘Let me go down there,’ said Lily, unexpectedly.

Despite the seriousness of the situation, Josh smiled. Lily certainly had the determination and grit required for the task,

and she was probably no more than half her brother’s weight.

‘This is a man’s job, Lily. Besides, you’d get yourself all tangled up in that dress.’

‘I’d take it off,’ she declared defiantly, the remark bringing more than one chuckle from the anxious miners who had been

listening to the exchange.

‘If we don’t do something soon the men trapped underground will try to do something for themselves,’ said Malachi, grimly.

‘They’re likely to bring the beam and everything else down on them.’

Josh knew he spoke the truth. The Notter miners would not be aware that the Sharptor men were above ground planning their

rescue. They’d believe they could rely only upon the scant resources of a run-down mine.

‘You’re right, Malachi.’ Josh arrived at a quick decision. ‘Very well, Darley. I’ll let you go down the shaft because you’re

our best hope to get through to the men down there. But you take care, you hear? I’ll be in enough trouble when your ma finds

out what I’ve let you do. If you hurt yourself my life won’t be worth living.’

He walked away from the head of the shaft, the shrill voice of Lily, raised in protest, ringing in his ears.

The rope harness hurt Darley beneath his armpits as he was lowered slowly down the mine shaft on the end of a stout rope.

Too excited to worry very much about it, he wriggled inside the harness in a bid to make it more comfortable.

In his hand, Darley held a thinner cord, being paid out alongside the rope that supported him. With this he could signal to the men at the top of the shaft. One pull to stop lowering or drawing up. Two tugs to lower him. Three

to pull him up.

Glancing up at the dwindling entrance to the shaft, Darley tried hard not to allow the fear that kept welling up inside him

take over. For the first time in his life he was doing something important for others, instead of having them take care of

him.

Darley was nineteen years of age now, but he looked much younger. It seemed to him he had been ill for most of his life. He

could not remember a time when he had not suffered from fatigue, or a cough that frequently left him helpless. He was always

being told he should not do this or that, at a time when the other members of his family seemed to be doing whatever they

wanted. He had been forced to spend a great deal of time inside the home. Nevertheless, he had made use of this by learning

all he could about everything contained in the many books his father acquired for him.

In spite of the situation in which he now found himself, Darley grinned nervously. His mother would be horrified if she knew

what he was doing. She had always molly-coddled him to the point of embarrassment. Josh had been right, she would make his

life unbearable if anything went wrong. Darley determined it would not.

He had almost reached the tangled wreckage that blocked the shaft now. Unhooking the paraffin-fed bull’s-eye lantern that

glimmered at his belt, he turned up the wick and directed the light downwards.

Protruding up through the tangle of wood, masonry and steel was one rounded end of the great iron bob that had brought down

tons of masonry when it crashed from its axis in the engine-house. In reality the bob consisted of two giant beams, linked side by side, the whole weighing more than sixteen tons.

It lay at an angle, the lower end apparently snagged on something in the shaft. Even with much of it buried in the tangle

of debris, the bob dwarfed Darley as he slowly descended beside it.

He gave a sharp tug on the cord as his feet landed on a timber. The men above ground were slow to respond. The rope to which

he was attached snaked over the wood beside his feet before jerking to a halt. He cursed at the tardiness of their reaction.

Another time, his life might depend on the speed of their response.

Darley swung the lamp to and fro, assessing the situation. He could see no obvious place where he might gain access to the

shaft below, but the thought came to him that he might prove small enough to squeeze through the space between the two linked

beams.

It was a dangerous manoeuvre. He had no way of knowing what had brought the beam to a halt in its plunge down the shaft. If

it were precariously balanced, his weight might prove sufficient to cause it to break away. It would then continue its drop

down the shaft, snapping the rope that supported Darley as easily as a strand of cotton, carrying him with it.

Squeezing through the gap between the two halves of the bob, he had to signal for more rope. When he had enough to go farther

down he swiftly discovered there was wreckage beneath the bob too.

Carefully, Darley tested his weight on a piece of timber that must have been at least six inches thick. It seemed to be firm

and he breathed a deep sigh of relief.

He was shining his lantern about him seeking a space where he might squeeze through when, without any warning, the timber

gave way beneath him.

He went with it for perhaps six feet. The supporting rope brought him up with a jerk that expelled the breath from his thin

body. It sent a sharp pain through his chest, as though his ribs had been crushed.

As he struggled with the pain, he could hear timbers bouncing off the sides of the tunnel. The sound grew fainter as they

crashed towards the water, deep down in the heart of the mine.

Three jerks on the rope, followed immediately by a single signal brought him back up to the bob. He supported himself in the

gap between the two halves for a few minutes, grateful to be able to take the weight from the harness about his aching ribs.

He had barely recovered his breath when he heard voices from the shaft beneath him. The sound made him forget his pain immediately.

‘Hello! Can you hear me?’ Darley shouted down the shaft, the sound loud in the confined space.

There was a cheer from somewhere a long way beneath him. Then a voice called, ‘What’s happening up there? Have you come to

get us out? We can’t climb any higher than the seventy-fathom level, the ladders have been torn away.’

‘The engine-house has collapsed. I’m here above you, sitting on the bob. It’s blocking the tunnel and will need to be blasted

clear before we can get a kibble down to you. Is anyone seriously hurt?’

‘Jack Hooper’s got a smashed shoulder and he’s bleeding a lot. Charlie Coombe’s got a broken wrist. That’s all.’

‘How many of you down there?’

‘Nine.’

Darley frowned. ‘They thought, up top, there were more.’

There was silence for a few minutes before the same voice replied, ‘Two men were working on the rods in the shaft when we came on shift. We thought … We hoped they’d gone to

grass before the accident happened.’

Anyone working in the shaft when the engine-house collapsed would have been swept away by the falling debris. Darley knew

this and so did the men to whom he was speaking.

‘I’ll need to go up top now and tell them of the situation down here. Stay well back in the level where you are now until

we’ve blasted the beam free. It’s likely to take a while.’

‘Will you be tackling it?’

Darley thought about it. ‘I expect so. There’s no one else skinny enough to squeeze through the tangle of wreckage here.’

There was some conversation between the trapped miners before their spokesman called up again. ‘Who are you, friend? We don’t

recognise your voice. You’re not a Notter man.’

‘I’m Darley Shovell, from St Austell. I came to Notter with the Sharptor men.’

‘Josh Retallick’s up top? Is he in charge of the rescue work?’

‘Yes.’

There was another cheer from the men below Darley and the unseen man called, ‘Then we’re going to be all right. Good luck

to you, friend. We’ll thank you properly when we set foot on grass once more.’

At the top of the Notter mine shaft Darley sat on the ground, surreptitiously rubbing his chest whenever he thought Lily and

the others were not looking. He did not want them to know just how much he ached as a result of his underground exertions.

‘We’ll need to try to blast the bob clear …’ Josh was talking to Malachi Sprittle. ‘How much powder do you think it will take?’

Malachi stroked his greying beard and shook his head dubiously. ‘I wouldn’t like to say, Josh. I’m not even sure it’ll work.

We’ll be swinging the powder down among the wreckage with a fuse attached. What it really needs is to be set into a hole in

the shaft wall, below the beam. That’s the only certain way of doing the job.’

Josh rested a hand on Darley’s aching shoulder. ‘You’re the only one who’s seen it down there, Darley. Is there any chance

that a man could squeeze through anywhere – and get back up again in a hurry?’

Darley thought of his tight squeeze through the bob and the wreckage tangled about it. He shook his head. ‘Not unless there’s anyone skinnier than me. I had a job to make it.’

‘Then we’ll have to try to lower the explosive into the wreckage and hope for the best …’

‘It’s all right. I’ll go back down there and do it.’

Now the words were out, Darley almost regretted uttering them. Those limbs and muscles that did not actually hurt, ached almost

as painfully. Besides, he had already performed a task that was more arduous than any he had ever before attempted.

Josh was aware of this. ‘You’ve done more than your share already, Darley. Don’t worry, our way might work.’

Carrying a mug of steaming tea that had been made for Darley by one of the mine women, Lily overheard the conversation. Indignantly,

she said, ‘Of course he’s done enough!’ Placing the mug carefully in her brother’s shaking hands, she said more gently, ‘Here,

Darley. Drink this, it’ll buck you up. It always does.’

‘Thanks, Lily.’ He took the cup, trying hard to control the trembling that threatened to spill the tea. ‘I can do with this

– but I’ve got to go down again.’

Looking up at his great-uncle, he said, ‘I told the men down there I would, Josh. There’s one of them with a smashed shoulder,

and they said he’s bleeding badly. If there was anyone else could do it I’d be more than happy for them to go instead. But

there isn’t. If it’s to work, the job needs to be done properly. That means boring a hole beneath the bob and trying to blow

it clear – and I’m the only one who can get through the wreckage.’

Josh knew Darley spoke the truth, but he had grave doubts about sending the sick young man down the shaft yet again. ‘Have

you ever set a charge before?’

‘No, but I’ve watched them doing it in the clay quarries. I know what needs to be done.’

‘Darley, you mustn’t. You shouldn’t have gone down the first time …’ Lily was close to tears.

He reached out a hand to her. ‘I know you’re worried, Lily, and I love you for caring, but I’ve got to do this. You understand.’

Despite her concern, Lily did understand. She understood her brother better than any other member of her family. She was aware of the pride and frustration

that lived within his frail body. Reluctantly, she bit her lip and nodded her head.

‘Are you certain, Darley?’ Josh was less easy to convince than was Lily.

‘Of course I am.’ Handing the cup he held to Lily, Darley made a supreme effort and pushed himself up from the ground. ‘Where

do I get the powder, and the tools for boring?’

Dangling on the rope in the shaft, the bulk of the bob jammed precariously above him, Darley paused in his work to take a

breather. The end of a spade-tipped drill protruded from a narrow hole in front of him. Another drill, secured by a rope,

dangled at his belt. In his hand was a heavy, short-handled hammer, also secured to his belt by a rope.

Such precautions were necessary. Three times he had dropped the drill before it was far enough in the hole to be safe. He

had lost count of the number of times the heavy hammer had slipped from his numb and achi

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...