- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

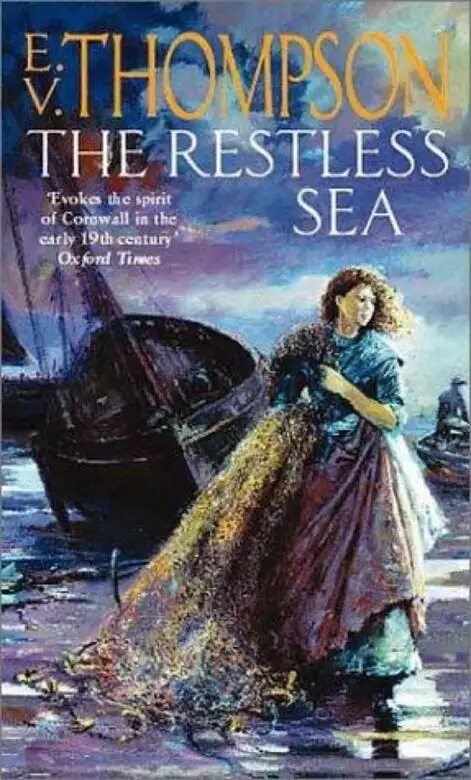

Synopsis

The Cornish coast of 1810 was alive with fishing boats, warships and smugglers. For Nathan Jago, a fishing business seemed the ideal place to invest his prizefighting winnings. But it wasn't all plain sailing to a wealthy future. For a start there was wilful young squire's daughter Elinor Hearle. And then there was Amy, with her passion for the sea and her fierce Cornish pride...

Release date: July 5, 2012

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 560

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Restless Sea

E.V. Thompson

‘Take him now …’

‘Your right, Ned lad. Use your bleedin’ right …!’

Ignoring the shouts of encouragement hurled at his opponent, Nathan Jago kept his left fist extended well in front of him,

not taking his eyes from his adversary’s face for even a moment. A quick flick of his right wrist was sufficient to wipe away

the perspiration that filtered through his thick, black eyebrows, threatening to blind him with its saltiness.

This was London Fields. Once the waste land beyond the walls of London Town, the fields were now at the heart of London’s

crowded ‘East End’ and home ground for Nathan’s opponent, Ned Belcher, champion prize-fighter of all England. A Hoxton man,

Belcher’s home was hardly more than a gargle and a spit away.

Suddenly, Ned Belcher tucked his chin down tight on his chest. Crouching low, he moved in to the attack, swinging heavy fists that were stained dark brown from hours of soaking

in a hardening mixture of vinegar and walnut juice.

One of the champion’s punches caught Nathan a glancing blow on the side of his face. Ducking low, Nathan slipped beneath the

next punch and brought his own fist across in a short, jarring blow that caught Belcher just below the right ear. Belcher

grunted with pain and dropped to one knee on the flattened grass. He kneeled there, shaking his head in the manner of a puzzled

dog that had just snapped at a wasp, and the referee declared it to be the end of a round.

Nathan walked gratefully to his corner and slumped down on the stool quickly provided by his seconds. Across the ring, Belcher’s

seconds ran to help their man back to his own corner before the precious thirty-second interval was over.

Spitting a mixture of wine and water on the muddy turf just outside the ring, Nathan asked, ‘How many rounds is that?’

‘Twenty-nine.’ A man of few words, Sammy Mizler had himself been no mean light-weight fighter, before a broken knuckle put

an end to his career. ‘The rest of the rounds are yours. Belcher’s kissed the gin bottle too often to take a long fight.’

Nathan looked across the ring to where Ned Belcher sat sprawled back in his corner, legs stretched out before him, the loose

flesh of his stomach spilling over the leather belt that held up his trousers.

Nathan thought that Sammy Mizler was probably right. Belcher was not the man he had been ten years before, when he fought

Hen Pearce to a standstill and took the title from him. Something had gone wrong along the way. Nevertheless, although Nathan was not a small man, Belcher

weighed at least three stone more – and he boasted a punch that could stun a bullock. He was an opponent not to be underestimated.

A murmur of concern rose from the vast crowd that stretched back as far as the dingy, grey, gardenless houses fringing the

northern edge of London Fields. Looking up, Nathan saw long, sulphurous fingers of mist beginning to reach out into the crowd.

The fog had been lurking among the close-packed houses of London’s crowded suburbs all day, held at bay only by the weak rays

of the autumn sun. Now it was evening, and as the last rays of sunlight left the stinking squalor that was Hoxton the fog

emerged to take over England’s ancient capital.

Nathan shivered. He knew he would have to chance the power of Ned Belcher’s fists in order to bring the fight to a rapid close.

As the fog moved closer to the ring, so would the crowd. When the fog became thicker, and the crowd was able to advance no

farther for the press of those in front, they would become first restless, then angry, and finally violent. This was a London

crowd. An ‘East End’ London crowd, ever ready to riot.

A disturbance of such a nature would bring the fight to a premature conclusion, the three-hundred-guinea purse being taken

home by neither man. And Nathan had plans for the money.

‘Time!’

From the side of the ring, the referee called on both men to advance to the centre and assume their stances to his satisfaction.

Ned Belcher’s seconds heaved their charge to his feet, and he lurched forward to the centre of the ring, raising his fists

when he was two paces away from his opponent.

Nathan’s unexpected assault took Belcher by surprise. Until now the challenger had been content to box a mainly defensive

fight, allowing the London champion to use up his strength. The two-fisted onslaught brought the crowd to their toes. Partisanship

was momentarily forgotten as they revelled in the sight of a skilled and superbly fit prize-fighter moving in for the kill.

As Nathan’s punches drove home, Ned Belcher retreated rapidly, his arms raised in ineffectual defence. At one stage his knees

buckled beneath him and he almost went down, but Belcher was an experienced and tough fighter. Lungeing forward, he wrapped

his arms about Nathan and held on grimly as Nathan pummelled him about the kidneys.

When Nathan attempted to throw Belcher from him, the heavier fighter whispered hoarsely: ‘Go easy on me, son. You’ll be an

old fighter yourself one day.’

So unexpected was the older fighter’s plea that Nathan stopped his punishing pummelling. Immediately, Belcher stepped a short

pace backward – then brought his balding head forward sharply. The unorthodox blow struck Nathan on the forehead, and a carnival

of coloured lights exploded inside his head.

It was only an instinctive sense of self-preservation that kept Nathan’s guard up as he was battered backwards across the

ring by Ned Belcher. Caught in his own corner, Nathan slipped on the turf, which had become saturated by liberal use of sponge

and water-bottle. As he fell, Sammy Mizler protected his boxer from the continuing assault, calling upon the referee to intervene.

The referee had to pull Belcher away from Nathan, so desperate was the ageing champion to ensure that Nathan would not make

the mark at the end of the half-minute rest brought about by the fall.

Nathan shook his head in protest as water poured over his head, and Sammy Mizler slapped his cheeks frantically in a bid to

bring him back to his senses.

‘What d’you think you’re doing out there? One minute I’m cheering myself hoarse because you’ve got him going. A moment later

you’re standing doing nothing, with Belcher’s arms about you. Did you think he was going to kiss you, maybe?’

Nathan grimaced. His head felt as though it had been resting against an exploding cannon. ‘He appealed to my better nature.

It won’t happen again.’

‘Better nature, you say? Is it an alms-giver you are now? Or are you fighting for the title of Champion of all England, and

a three-hundred-guinea purse? Oi! But the ref’s calling “time” now. You’d better make up your mind what it is you want.’

Nathan jumped to his feet and was waiting in the centre of the ring when Ned Belcher came to the mark. Hardly giving him time

to raise his guard, Nathan launched an attack that drove the champion before him. It was too much for Belcher. He walked heavily,

heels to the turf, the elasticity gone from his legs. Forced to a neutral corner, Ned Belcher lay back against the taut rope,

and his hands dropped helplessly to his sides. Blood dribbling from a cut lip, he stood slack-jawed, staring blankly at Nathan.

For one brief moment, Nathan hesitated. Then he remembered Belcher’s whispered appeal – and the head butt that had followed.

He brought across a straight left that caught Belcher on the side of his jaw. The champion sagged at the knees; but, before

he struck the ground, Nathan landed a hard right between Belcher’s eyes, and every man in the hushed crowd heard the crack

of knuckle upon bone.

Belcher’s seconds darted forward to drag their man to his corner as Nathan made his way back to Sammy Mizler.

‘You’ve got him, Nathan. You’re the new champion, already.’ The phlegmatic Jewish second was more excited than Nathan had

ever seen him.

Declining to take the stool for the mandatory thirty-second break, Nathan stood nursing the aching knuckles of his right hand,

looking to where Ned Belcher’s seconds worked frenziedly on their champion. He, too, doubted whether Belcher would come to

the mark for the next round. The punch that had put him down was one of the hardest Nathan had ever thrown.

At a nod from the timekeeper, the referee called upon both fighters to take up their stances in the centre of the ring. Confidently,

Nathan made his way to the mark, helped on his way by a resounding slap of encouragement from Sammy Mizler.

Ned Belcher’s corner was the scene of utter confusion. The seconds had their champion on his feet, but he seemed not to know

what was happening and was shouting in near-hysteria. Nathan could not hear his words because they were drowned by the noise

of the crowd, many of whom had bet large sums of money on the locally born champion.

To make matters worse, thick fog was now rolling across the fields. Unable to see what was happening, the spectators at the

rear of the huge crowd were pressing forward, clamouring noisily to be told what was going on inside the thirty-foot-square

ring.

Ned Belcher was dragged to the centre of the ring by his seconds just in time to beat the referee’s deadline. As the seconds

scuttled back to their corner, Nathan took his stance. Ned Belcher advanced for only two shuffling paces and then he dropped

to his knees, his hands going up to cover his face.

Nathan hesitated, in a quandary. A fighter was not allowed to go down without a punch being thrown but, equally, a man on

his knees was deemed to be ‘down’ and should not be struck.

The crowd entertained no such doubts. Angered at Ned Belcher’s unprecedented behaviour, they called to Nathan to ‘finish him

off’. Their howls of rage mingled with the cries of those frustrated spectators prevented by fog from seeing what was happening

inside the ring.

As the fog began swirling across the ring, the noise reached an ugly crescendo. It was now that Nathan saw tears begin to

seep between Ned Belcher’s fingers.

Convinced at last that this was no trick on the part of the champion, Nathan advanced cautiously towards him and laid a hand

upon his head.

Ned Belcher reached up and grasped Nathan’s hand in his own. In a hoarse, terror-filled voice, he whispered desperately: ‘I

can’t see! I’m blind, boy. So help me, I’m blind!’

Nathan was still wary of the man kneeling before him. Ned Belcher was an ageing and weary champion, desperate to keep his

title.

‘It’s the fog, Ned. A few more minutes and it will have closed in altogether …’

The battle-scarred fingers closed tightly on Nathan’s hand. ‘It’s not fog, boy. I’ve lost my sight. I’m blind as a maggot.

God help me …’

The referee was as uncertain as Nathan.

‘Get up and fight, Ned. Get to your feet now, or I’ll have no option but to give the title and purse to Jago.’

It was doubtful if Ned Belcher heard the words, so loud was the din from the disgruntled spectators. He turned his head this

way and that, in total confusion.

Nathan was no longer in doubt. The last blow he had landed had robbed the champion of his sight.

‘He says he’s blind. I believe him.’

Clods of earth and stones began landing in the ring, hurled by the howling spectators. The situation was rendered more malignant

by the foul-smelling fog that now reduced visibility to no more than a few yards. The referee waited no longer.

Raising Nathan’s free arm, he declared him the winner of the contest, and the Champion of all England. Thrusting a bag containing

the three-hundred-guinea purse at the new champion, the referee scurried away. Ducking beneath the rope, he was quickly swallowed

up by the fog and the angry, gesticulating crowd.

Sammy Mizler appeared at Nathan’s side, an arm crooked above his head to shield himself from the volley of missiles bombarding

the ring from every direction.

‘Let’s go before half that crowd gets in the ring with us. They’re out for blood – yours mainly. But I’ve no doubt the colour

of mine will serve them as well.’

Fighting had already broken out among the crowd at the ringside, and now one of the ropes sagged inwards beneath the weight

of struggling bodies.

Snatching his shirt from the worried Sammy Mizler, Nathan turned to where Ned Belcher was being helped to his feet by equally

anxious seconds. Thrusting the purse into Belcher’s groping hands, Nathan shouted: ‘Here … It’s the purse. Put it to good

use. Buy an inn …’

The side of the ring collapsed. As the crowd spilled through, Ned Belcher was hustled off; and Nathan Jago, undisputed Champion

of all England in the illegal sport of prize-fighting, followed after.

The date was 10 August 1810. At the age of twenty-seven, Nathan had achieved the ambition that had been his since he had left

the Navy to become a prize-fighter five years before.

The day had not started well for Elinor Hearle, and it became progressively worse as it wore on. It began when her maid failed

to awaken her and Elinor over-slept. When the maid finally put in an appearance she had such a dreadful chill that Elinor

sent her straight back to her bed.

Then, when Elinor reached the stables to take her stallion Napoleon for a morning gallop, the horse had gone. The animal had

been taken out by the groom in the belief that Elinor was forgoing her usual morning ride.

The decision to exercise the stallion, although taken in the best interests of the horse, cost the groom his post at Polrudden

Manor.

The nagging realisation that the groom had been dismissed unjustly did nothing to improve Elinor’s humour as the day wore

on. By noon a foul temper possessed her. The few servants in the big house did their best to keep out of her way, but it was not easy. Sir Lewis Hearle, Elinor’s father, was returning from London today,

and there was much to be done about the house.

Elinor’s mother had died when she was a child, and Sir Lewis, Member of Parliament for the nearby port of Fowey, was away

in London for most of the year, engaged in parliamentary affairs. He hoped one day to gain high office, and so recoup the

dwindling family fortunes. Consequently, the task of running the household staff fell to Elinor.

Elinor was a very capable housekeeper, but the responsibilities thrust upon her so early in life combined with an unusually

strong character to produce a wilfulness that had frightened away even the most ardent suitor. Elinor was twenty-five years

old now and one of the most attractive girls in the district, but there was no hint of romance in her life. Women in the nearby

village of Pentuan shook their heads in disapproval as she galloped through the village on her high-spirited stallion, sitting

the horse like a man. They swore that Elinor, heiress to the decrepit manor house and scant fortunes of Polrudden, would end

her days an impoverished and eccentric spinster.

If Elinor knew of their disapprobation, she did not allow the knowledge to alter her way of life – and there was not a villager

who dared express such views to her face.

Sir Lewis Hearle had written to tell Elinor that he would be travelling from London on the Royal Mail coach, due to reach

the Queen’s Head inn in St Austell at three o’clock that afternoon. Elinor was to meet him there.

Usually, she would have travelled in a chaise driven by the groom but, smarting under her injustice, the groom had already

left Polrudden. Elinor had gone to his house, intending to give the conscientious man another chance. She had been met by

his red-eyed wife and three wailing children, and had learned that he had gone to seek the recruiting sergeant in Bodmin Town

to take the King’s shilling. He had told his wife that he preferred the bayonets of Bonaparte’s army to the tongue of the

mistress of Polrudden.

Because of this, Elinor was obliged to take the smaller gig and drive the horse herself.

It was a distance of five miles to St Austell, and Elinor set off rather later than she had intended. She drove briskly from

the house, situated high on the hill above the busy little fishing village of Pentuan, urging the horse on through the narrow,

high-banked lanes.

It was a hot day and, unlike her own riding-horse, the pony pulling the gig had not been exercised daily. Lazy days and lush

summer grass had made it fat and out of condition. By the time they had covered less than half the distance to St Austell,

the steep hill and Elinor’s urging had brought the horse out in an unhealthy sweat.

There was a well-used watering-place nearby and, cursing the delay, Elinor turned aside to give the pony a brief rest and

the opportunity to drink.

The watering-place was no more than a shallow pond, fed by a spring, and the ground about it muddy and uneven. Climbing down

from the seat of the gig, Elinor led the animal to the water’s edge. Suddenly, her foot slipped and she tugged hard at the

bridle. Startled, the horse threw back its head and pranced nervously in the shafts of the gig. Elinor’s feet went from beneath her, and she fell heavily in the pond, catching her dress

on a piece of broken fencing as she went down.

Scrambling out as quickly as she could, Elinor grabbed the horse’s trailing reins before the animal could bolt. Backing horse

and gig away from the slippery bank of the pond, she secured the reins and then examined the state of her dress.

She was soaked through, and muddied from shoulder to toe.

The ill-humour that had been simmering inside her since early morning flared up once again. She cursed the horse, the pond,

and the groom she had dismissed that morning. Not until it was out of her system did Elinor pause to think of what to do next.

She could not continue her journey to St Austell in her present state, and to return to Polrudden Manor to change her clothes

was out of the question. She was late already.

About a quarter of a mile away was the cliff-edge farmhouse of Venn. Leading the horse and gig, Elinor made her way there.

A small farm of some fifty acres, Venn had a steep, difficult-to-work patchwork of fields. It belonged to Elinor’s father,

but was currently rented out to a young yeoman farmer named Tom Quicke. Elinor knew he had married no more than six months

before and hoped she might borrow a dress from his young wife.

The first sight of the farmhouse immediately raised her hopes. For many years it had been occupied by a retired sea-captain

who had merely played at being a farmer. Widowed for more than thirty years, the sea-captain had allowed the farm and himself to run down towards the end of his ninety-four years. Tom Quicke had changed

all that. Gates had been repaired and rehung, and the small farmhouse was bright with new paintwork.

The door of the house stood open and, looping the reins of her horse over a fence-post, Elinor walked inside. She found herself

in a low-beamed room with large blue-slate flagstones on the floor and only one small, open window to allow light inside.

Full of cool shadow, the room was as clean as the outside of the farmhouse had promised.

Elinor could hear sounds coming from the back of the house and, ducking through a low doorway, entered the farmhouse dairy.

A young woman with dark hair tied neatly behind her neck stood at a stone sink. She was busily scrubbing the dismantled workings

of a butter-churning machine.

As Elinor entered, the girl looked up, startled at the sudden appearance of this dishevelled, uninvited visitor.

Elinor wasted no time on irrelevant greeting. ‘I’m Elinor Hearle and I have had an accident at the watering-place. I need

to borrow a dress – and be quick about it. I’m to meet my father in St Austell at three.’

Flustered, the girl stepped back from the sink with soap suds clinging to her bare arms. Dropping Elinor a hurried curtsy,

she said: ‘I’m Nell, ma’am. Wife of Tom Quicke.’

Elinor thought the girl looked hardly old enough to be a farmer’s wife, but she had neither the time nor the inclination to

exchange chitchat with the young wife of one of her father’s tenants.

‘Well, don’t stand there gawping. Help me off with these clothes, then run upstairs and bring me some of your dresses to choose

from.’

‘I … I haven’t got many, ma’am.’ The girl moved towards the door as Elinor began impatiently unfastening those hooks she was

able to reach on the back of her dress. ‘You’d best come upstairs to the bedroom. Tom will be in from the fields in a minute

or two …’

‘Then Tom will just have to go out again. I’m not staying in this dress for one moment longer. Help me undo these wretched

hooks.’

Hastily drying her hands on her apron, Nell Quicke moved behind Elinor and unfastened the metal hooks securing the dress.

As she worked she made low sounds of distress.

‘You’ve made a terrible mess of this, ma’am. ‘Tis not only muddy, it’s torn, too.’

Elinor wriggled the dress down over her hips and it dropped to the floor at her feet. Picking it up, she examined it quickly,

then threw it down again petulantly.

‘Damn!’

‘I can wash and mend it for you, but it won’t be ready for you to wear again today.’

‘Then take me upstairs and show me what you have. You must have something.’

Without waiting for the girl’s reply, Elinor strode from the dairy and headed for the staircase in the corner of the living-room.

On the way she swept past Tom Quicke, who had just entered the house from the yard. His mouth dropped open at the sight of

his titled landlord’s daughter advancing upon him dressed only in a wet and bedraggled petticoat. But he hardly had time to snatch the hat from his head before Elinor passed by without

a word, Nell in close pursuit.

There were two doors opening off the head of the stairs. One door stood open, displaying a bed, a handmade rag carpet, and

marble-topped washstand. This was quite obviously the bedroom in use by the Quicke family, and Elinor swept inside. She looked

in vain for a wardrobe.

With a murmured apology, Nell Quicke slipped past her and dropped to her knees beside a leather chest, hidden on the far side

of the bed. Of a type used by sea-captains, it had been left behind by the previous occupant of Venn. Raising the lid, Nell

Quicke reached inside and carefully lifted out three neatly folded dresses.

Two Elinor rejected immediately. Of gaudy silk, they had evidently been bought for Nell Quicke when she was a much younger

girl. The third, made from coarsely woven woollen cloth, was more suitable than either of the others, but it was well worn.

Elinor looked questioningly at the farmer’s young wife, and Nell Quicke met her glance with an expression that was a mixture

of embarrassment and defiant pride.

‘That’s all I’ve got, ma’am. My father’s a poor man. I came to Tom with no dowry.’

For a fleeting moment, Elinor felt an unexpected surge of sympathy for this wife who had so little – and was unlikely to gain

more while her husband worked Venn Farm as a tenant. But Elinor had a coach to meet. Taking up the woollen dress, she held

it against her body. ‘Then this will have to do. But first I’ll need a wash. I’m covered in mud.’

Nell Quicke hurried from the room. Moments later Elinor heard the sound of urgent whispering from downstairs as pans and kettles

clanged upon the kitchen fire.

Elinor’s expression softened. There was an intangible, calming quality about Nell Quicke. It was not difficult to understand

why Tom Quicke had been ready to take his young wife without a dowry.

Nell Quicke returned with a jug of hot water and convinced Elinor that her petticoat would have to be left behind, too. Not

only was it too elaborate to be worn beneath Nell’s simple woollen garment, but it was also as wet and mud-stained as Elinor’s

dress.

After a hurried wash, Elinor put on Nell Quicke’s dress. She was not able to confirm Nell Quicke’s statement that the dress

fitted well. When she asked for a mirror, Nell Quicke produced a small and cheap hand-mirror, proudly declaring it to be a

wedding gift. It was the only mirror in the house.

When Elinor went outside, she found Tom Quicke brushing down her pony.

‘I gave him a drop of water, Miss Hearle,’ he said as he handed her up into the gig. ‘He seemed to be thirsty.’

Guiltily, Elinor recalled that she had been so concerned with her own plight that she had not given the horse a drink at the

watering-place.

‘I’m obliged to you, Quicke.’

To his wife she said: ‘Bring my clothes to Polrudden when they’re washed and mended. I’ll see you’re paid for your trouble.’

Flicking the reins over the horse’s back, Elinor set the animal off at a smart trot, heading back along the farm track that

led to the St Austell road.

When she was out of sight, Tom Quicke scratched his head ruefully and replaced his battered hat. ‘That’s the first time I’ve

spoken to Sir Lewis’s daughter. I can’t say I’ve been missing much. Attractive she may be, but she’s no more grateful for

anything that’s done for her than her father.’

‘Oh, she’s grateful enough, Tom. I could see that.’ Nell Quicke took her husband’s hand as they walked inside the house together.

‘She’s just not used to thanking folks, that’s all. Life can’t be easy for her up at that big house – alone for most of the

time, I shouldn’t wonder. I feel sorry for her.’

They had reached the kitchen now, and Tom Quicke looked at the dirty but expensive dress and petticoat lying on the table.

Elinor Hearle probably had two or three wardrobes crammed with such clothes. All of Nell’s treasured possessions were packed

inside a single sea-chest – and yet she felt sorry for Elinor Hearle!

Tom Quicke squeezed Nell’s hand affectionately. He knew he had married a very special girl and was very much in love with

his young wife.

Elinor Hearle arrived at the Queen’s Head inn a few minutes after three o’clock. There was no sign of the Royal Mail coach.

In answer to her question, a serving-girl informed her that it had not yet arrived.

There was a great deal of noise coming from the Queen’s Head and the other inns of the town. Elinor remembered that this was

the last Friday of the month, the day when both the weekly paid labourers and the more highly skilled miners received their pay.

St Austell was surrounded by tin and copper mines. In recent years the opening of the china-clay quarries to the north of

the town had begun to change the age-old landscape of the Cornish countryside, throwing up tall mounds of china-clay waste,

and attracting a great deal of labour to the area. The quarry-owners, members of the local trading fraternity, had learned

from their mining associates that a great deal of trading profit could be gained by paying their workers in the St Austell

inns. Much of the hard-earned money would return to the businessmen over the tavern bars. More would be spent later in the

nearby shops, on gifts for irate wives whose meagre housekeeping money had been further depleted in the convivial atmosphere

of a smoke-filled ale-house.

For almost an hour Elinor sat in the gig, growing ever more impatient and annoyed by the remarks and hopeful attentions of

passing miners in varying stages of insobriety.

When half-past four came and the mail coach had still not arrived, Elinor tied the pony to a hitching-post outside the Queen’s

Head and sought the shadows of the archway that led to the yard beside the inn.

Inside the yard was a brewer’s wagon. It had arrived earlier in the afternoon, heavily laden with barrels of locally brewed

ale. Unloading the barrels and trundling them to the cellars of the Queen’s Head inn was hard and thirsty work, calling for

constant refreshment for the drayman and his mate. By the time the last full barrel had been replaced on the wagon by an empty

one, both brew

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...