- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

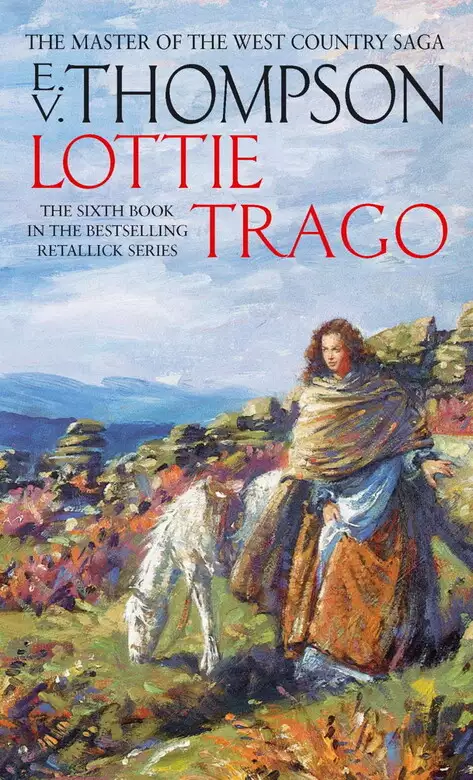

Cornwall 1864. Josh and Miriam Retallick return home from Africa to find the chimneys smokeless, the men and women hungry, and Lottie, guarding goats on Bodmin Moor, an unmistakable Trago in looks and spirit. Josh soon takes stock of these hard times to become a new power in his native land. While Jane Trago, a sensual woman but an unfeeling mother, sweeps in like an ill wind to take up HER new trade in the local tavern. Against the fluctuating fortunes of the Sharptor mine we follow Lottie, as she is drawn first to Jethro Shovell, a dedicated trade unionist, and then to the smooth-talking aristocratic Hawken Strike. Little knowing how heavily the sins of the mother can fall - even on a daughter as wild as the moor...

Release date: July 5, 2012

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Lottie Trago

E.V. Thompson

Clustered about the giant three-masted vessel were small boats of every conceivable type and size, filled with awed sightseers and excited relatives of those on board. They had met the Great Britain at the mouth of the river, some anxious to catch a first glimpse of long-absent loved ones, others to marvel at the 322–foot length of the ship that had been launched as the largest vessel afloat.

As the strip of dirty water between ship and jetty was squeezed to nothingness and stout ropes began to stitch ship to shore, the wind toyed with a hundred delicate handkerchiefs held aloft in greeting.

Among the passengers crowding the rail were a man and woman who knew no one on the quayside, yet every excited glance from the shore rested upon them before moving on. Both had the deep tan common to those who have spent many years outdoors in the fierce African sun. He stood tall, with an impression of fitness, head and shoulders squared to blue skies and far horizons, unbowed by winter rains and chill winds.

Josh and Miriam Retallick viewed the scene on shore with a confused mixture of emotions. Joy, certainly, but sadness too, together with anticipation and apprehension.

‘You’re hurting my shoulder!’

The surprised complaint came from the small girl standing in front of Josh and upon whose thin shoulders his hands had tightened unconsciously.

‘I’m sorry, Anne,’ Josh apologised immediately.

‘I didn’t mind Miriam’s hands squeezing me.’ Nell Gilmore gave her six-year-old sister a scornful look that contained all the superiority a sister senior by two years could muster.

‘Having two young girls with us isn’t how I imagined our homecoming would be.’ Josh spoke quietly so the girls would not hear, but Nell and Anne were too busy cheering along with three hundred fellow-passengers as the steel stern of the Great Britain bumped against the quayside.

‘It’s more than either of us could possibly have hoped for eighteen years ago …’

Looking past the waiting quayside crowd, Miriam saw the acres of dockland that were the pride of Liverpool…. The thought made her smile. Pride of Liverpool had been the name of the ship taking them from England and home all those years before.

They had not been first-class passengers on that occasion. Josh had been a prisoner under sentence of transportation to Australia, convicted of a treasonable conspiracy. Miriam had taken passage on the same ship with Daniel, their three-year-old son, with little expectation of ever seeing England again.

When the Pride of Liverpool foundered on the Skeleton Coast of South West Africa, Josh and Miriam were cast ashore in a land beyond the jurisdiction of Great Britain. Here, Josh had built a new life for his family and they prospered.

Eighteen years …. She and Josh had been only twenty-two then. Almost the same age as Daniel was now. If only Daniel was returning with them now Miriam’s happiness would be complete. But Daniel had established a profitable trade-route that extended across half the breadth of Africa. He would one day be a very wealthy man indeed.

‘Look, there’s a band!’ Nell’s excited cry broke into Miriam’s thoughts. As the two young girls chattered excitedly at the scene in front of them she smiled, yet there was a sadness in her smile.

Nell and Anne Gilmore were orphans. Sole survivors of a missionary party which had trekked to the heart of Africa, totally unprepared for the perils they encountered along the way. One by one the members of the party had died. Nell’s and Anne’s parents had been among the first. When there was only one man and the two girls left alive they had been found by bushmen and handed over to Daniel Retallick. Soon afterwards the girls’ companion also died, and Josh and Miriam took charge of the young sisters. When the opportunity occurred to return home to Cornwall, it seemed natural for the girls to come with Josh and Miriam. They had no one else.

Miriam reached across and took Josh’s hand. His start of surprise indicated that his thoughts had also been far away. As he returned his wife’s smile the final rope linking the SS Great Britain to the quay was secured. They had arrived in England. Another forty-eight hours should see them home in Cornwall.

The ageing, leather-sprung coach slid and lurched from pothole to wheel-carved furrow as it negotiated the steep hillside road skirting the eastern rim of Cornwall’s Bodmin Moor. On the high, exposed driving seat a coachman hauled on the reins and cursed the snorting, high-stepping horses as they shied at a steep, downward slope. He would have cracked the long, plaited leather thong of his whip about their ears had he not needed both hands to fight the long reins. Heavy showers in the last few days had made the indifferent road treacherous. A momentary lapse could result in coach, passengers and horses sliding off the road and plunging to the bottom of the mine-torn valley, seven hundred feet below.

Inside the coach the two young Gilmore girls squealed, half in fun, half through fear at the erratic movements of the vehicle. On the seat between them Miriam clung to both as well as she could. She had long given up uttering comforting platitudes, choosing to utilise her energies to prevent the girls from suffering injury.

On the opposite seat, Josh sat alone, impervious to the violent movement of the coach, so engrossed was he with the scene outside.

‘We should be able to see Sharptor soon …’ Josh slid along the polished leather seat and shifted his gaze to the window on the other side of the seat as the uncertain camber of the rough road tilted the coach away from the valley.

‘Thank the Lord for that. It means the journey’s almost over. These last few miles have been worse than the storm we went through in the Bay of Biscay.’

Josh looked at Miriam in surprise as the coach levelled out on a section of road recently filled and graded. ‘But we’re almost home. This is Cornwall … the moor. Here, let me take Anne.’

Reaching across the gap between the two seats, Josh took the six-year-old Gilmore girl from Miriam and sat her upon his knee. ‘Yes, we’re almost home, young lady. This is where you’ll be living – just around the corner of the next hill.’

‘I don’t like it. There are too many chimneys and smoke … and things.’

Josh met Miriam’s raised-eyebrowed glance and he grimaced. ‘Those chimneys belong to the mines where men and women around here earn their living – but not enough chimneys are throwing out smoke. I’d say all isn’t well with the copper-mining industry in Cornwall.

‘I don’t care about smoky old mine-chimneys. I liked it better in Africa.’

Once again the two adults in the coach exchanged glances, but this time it was Miriam who spoke. ‘We’ve left Africa behind for good, Anne. Sharptor will be your new home. You’ll enjoy it more when you see the house – and make friends to play with.’

‘Look! There’s a pig … with lots of babies.’ Nell’s excited observation caused the younger sister to wriggle free of Josh’s grasp and join her at the open coach window.

‘It’s good to see them behaving as children should,’ said Miriam quietly.

Josh nodded, his eyes taking in another smokeless mine-chimney. Something was very wrong. It was mid-week and the mines – many more than he remembered – should have been in full production, smoke belching from tall granite chimneys, the clattering of ore stamps echoing from tor to tor. Yet less than half were working.

An unexpected shout of ‘Whoa!’ from the coach driver brought horses and coach to a sliding halt.

Putting his head out of the open window, Josh saw a line of men standing across the road. They were dressed as miners, but the pick-axes and long-handled shovels they carried were not implements of work today. Each tool was held in the manner a soldier might hold a bayonet-fitted rifle, or a pike.

‘Where you making for?’ One of the miners, a burly, narrow-browed, bearded man put the question to the coach driver.

‘Up to Sharptor,’ was the coachman’s reply.

The miners closed in on the wagon. ‘What’s your business on the tor? ’Tisn’t a place for a coach and horses.’

‘He’s taking me to my home,’ Josh swung open the door and stepped stiffly to the ground. He was puzzled by the attitude of the miners, but grateful for an opportunity to stretch his aching legs. ‘My wife and two young girls are inside. We’ve all been travelling for a long time, so I’d be obliged if you’d stand aside and let us pass.’

‘Who are you?’ The miners’ shovel-wielding spokesman stood his ground. ‘I’ve not seen you before – and I’ve been working a core at the Sharptor mine for ten years.’

‘I know him, Marcus.’

The words were spoken by a young, beardless miner, who could have been no more than seventeen years old. ‘It’s Josh Retallick on his way home from Africa. He wrote telling my ma he was coming.’ The young man extended his hand towards Josh. ‘You won’t know me, Mr Retallick. I’m Jethro Shovell – Cap’n Shovell’s son.’

Josh shook the young miner’s hand warmly, ‘I’d have recognised you anywhere. You favour your mother. How is she – and your brother? He was no more than a babe-in-arms when I left Cornwall.’

Jenny Shovell and Josh had been like brother and sister when both were young. It seemed a lifetime ago …. It was a full life span for many of the young men employed in the highly dangerous copper and tin mines of Cornwall – as Jethro’s next words proved.

His face displaying anguish, he said, ‘My brother was killed in a mine accident, two years ago. A ladder broke loose when he was on his way down. His death tore Ma apart for a while.’

‘I’m sorry, Jethro. I really am.’ Josh seized at a means of changing the subject. ‘What’s going on here? Why are you and the others mounting a guard on the road?’

Jethro Shovell looked suddenly ill at ease and the miner he had called Marcus answered Josh’s question. ‘The machinery of the Sharptor mine’s been put up for sale. If we let it go the mine’ll never work again – and neither will anyone in Henwood.’

Josh was shocked, but not altogether surprised. ‘By the look of things it isn’t the only mine to shut down hereabouts. Coming across the moor I counted more smokeless chimneys than working ones.’

‘The difference between us and them is there’s still enough ore in Sharptor to give us all a living if the mine was properly managed. It’s a good mine.’ Jethro Shovell spoke passionately. ‘But you’ll know that yourself, you built the engine for the mine.’

‘That was more than twenty years ago, Jethro. Times change. So do mines—’

‘—and mine owners,’ the interruption came from another of the miners, an older man than the others. ‘Theophilus Strike would have owned the Sharptor mine when you were here. He kept it until he died, only six months since. Nigh on ninety, he was, but a better man than his nephew, for all that.’

There was a murmur of agreement from the other miners and Jethro Shovell explained, ‘First thing Leander Strike did was try and sell shares in the Sharptor mine. Said he needed to raise capital if the mine was to keep going. We all reckoned at the time he wanted to raise money to pay his gambling debts. Whatever the reason, it didn’t work. There’s been too much money lost in mining in recent years. With the price of copper dropping almost daily no one in his right senses would buy mining shares.’

‘So he’s put the machinery up for sale?’

Josh looked at the grim faces of the miners as they nodded confirmation. There was something about a Cornish miner that was unmistakable. Josh would have recognised their origin and calling had he met with them anywhere in the world.

‘He’ll not find a buyer so long as we’re here – and there are others guarding the roads from Darley and Berriow Bridge.’ Jethro Shovell spoke of the two other roads which approached Sharptor. Both merged in Henwood village, the houses of which were visible little more than a half-mile away.

Suddenly embarrassed by the intensity of his feelings, Jethro Shovell added sheepishly, ‘But you’ve had a long journey. You and Mrs Retallick will be wanting to get the girls home. We’ve held you up long enough listening to our troubles. You’ll find a nice warm fire burning at your place up on the tor. My ma and yours must have cleaned and warmed the place through twice a day for weeks now. They’re that excited about you coming back from Africa.’

Miriam smiled at the young man. This was the homecoming she had dreamed about. If only Daniel were here … but she was determined to allow nothing to spoil this day for her.

As Josh climbed on board, the coach started off with an unannounced suddenness. Miriam had to hold the two girls tight to her to prevent them sliding off the seat. She smiled at each of them in turn. They were her family now. The girls had survived an ordeal that would have unbalanced the mind of a grown man, and they had no one else. She hugged them closer. Six-year-old Anne yielded to her embrace, but Nell, thin and wiry and two years senior to her sister, wriggled free and moved closer to the open window.

‘Look … soldiers!’ Nell suddenly pointed to where a small cluster of cottages and a tall, grey mine building had come into view beyond the yellow gorse and dark green fern, higher up the slope.

‘It’s militiamen … at the Sharptor mine,’ Josh peered from the window. ‘Jethro Shovell never mentioned anything about soldiers.’

‘He and the others probably know nothing about them. The militiamen will have marched across the moor from Bodmin. If the miners fall foul of them there’ll be trouble. Serious trouble.’

Not far from the road a young girl armed with a stick was noisily driving a small flock of goats away from the fern towards a grassier spot. Her faded and badly patched dress was much too small for her and had probably been handed down at least four or five times.

Calling from the window for the coachman to halt the vehicle, Josh shouted to the goat-girl, ‘You! Girl!’ He needed to repeat his words three times before she turned her face towards him.

‘Come here … I want you.’

The girl seemed reluctant to comply, but after shooing the goats farther from the dense-growing fern she came half the distance to the coach before stopping once more.

‘What d’you want with me?’

‘I need a message taken to some men waiting along the road towards the Phoenix.’

‘I’ve got Mr Barnicoat’s goats to look after. If I don’t keep ’em out of the fern they’ll eat it and blow themselves up fatter ‘n pigs.’

‘Take the goats with you. They’ll come to no harm. I’ll give you threepence.’

‘I’ll not put my job at risk for threepence!’ The girl’s voice was heavy with scorn, coloured by a rapid assessment of how much more she might ask from a man who wore a suit and rode in a carriage. ‘It’ll cost you a shilling – at least.’

Miriam’s chuckle was no salve to Josh’s exasperation.

‘If it wasn’t so important I’d tell the little hussy to go to hell. As it is …!’ Josh fingered a silver coin from his pocket, ‘All right – but hurry. You’ll find Jethro Shovell up the road with some miners. Tell them there are militiamen up at Sharptor mine. They should keep clear of them.’

The coin spun through the air and the girl pounced on it as it hit the ground. Backing away, she reached the goats before calling out, ‘The miners already know about the militia. Me and my brother saw them coming down off the moor and I sent Jacob off to tell Jethro. You must have passed him on the road.’

‘Why, you …!’

Miriam’s laugh cut through her husband’s not-too-serious anger. ‘Doesn’t she remind you of someone?’

‘Who?’

‘Me, when I was ten or eleven and living in the cave up on the moor.’

Josh looked again at the cheeky, young goatherd. There was a certain likeness … but Miriam was calling through the window.

‘What’s your name, girl?’

‘Lottie. Lottie Trago. What business is it of yours?’

Miriam drew in her breath sharply. Her own maiden name had been Trago.

‘What’s your mother’s name?’

‘I ain’t got no mother … nor a father, neither. I live with my Aunt Patience.’

‘I knew it!’ Miriam was filled with a confusing mixture of emotions. ‘Patience is my sister! The girl must be Jane’s daughter. That means Jane must be dead. She was the youngest of the family, too.’

The ragged young goatherd had turned away and was driving her charges across the moor. She intended putting a good distance between herself and her duped benefactor in case he tried to retrieve his shilling.

‘Lottie!’

The young girl turned her head, but kept walking.

‘When you return home, tell your Aunt Patience to come up to Sharptor as soon as she has a minute to spare. Tell her … tell her Miriam’s come home.’

THE COACH was brought to a halt for the second time that day as it skirted the Sharptor mine. This time the men standing in the road wore the scarlet coats of militiamen – and they were armed with long-barrelled rifles.

Before the part-time soldiers could ask the coachman his destination two men hurried from the mine. One was tall, thin and balding. His companion wore the unfamiliar uniform and insignia of a police inspector.

‘I’m Leander Strike. This is Police Inspector Coote. Are you here to look over the mine machinery? You’ll find it in splendid condition. The engine’s a superb model.’ Leander Strike spoke eagerly … far too eagerly. ‘You’ll find the price equally attractive, I’m sure.’

‘You have no need to tell me anything about the Sharptor mine engine – but I’m not here to buy mine equipment. I’m on my way home – though I’m being stopped and asked so many questions it’s likely to take twice as long as it should.’

Leander Strike’s attitude underwent an immediate change. His eagerness was replaced first by disappointment, then by suspicion. ‘There’s nothing on the moor beyond here but mine cottages – and you’re no miner.’

‘I own the old farmhouse farther up the hill beyond the mine. I’ve been away for some years, but now I’m home again.’

The mine owner stared at Josh as though looking at a ghost. ‘My uncle sold the house and land up there many years ago … to Josh Retallick.’

Police Inspector Kingsley Coote, a grey-haired man with a heavy, drooping moustache, frowned. ‘When I was a young constable in Bodmin I remember the arrest of a lad named Josh Retallick. Must be all of twenty years ago now. He took a leading part in a riot down at the port of Looe, if my memory serves me right. Convicted at Bodmin Assizes of “conspiracy to treason and sedition” – a capital offence. But instead of hanging he was sentenced to transportation. For life, as I remember.’

‘Your memory’s excellent, Inspector.’ Josh met the challenge of the inspector’s eyes. ‘I was convicted of a conspiracy. Wrongly convicted. I have a Queen’s pardon in my luggage, together with a copy of the guilty party’s confession. Now we’ve got that out of the way, I’d like to take my wife and these two young girls home. We’ve all had a long journey from the heart of Africa and are very weary.’

‘Africa, you say? Africa?’

Leander Strike was less impressed than his companion. ‘You might have a pardon, Retallick, but there’s seldom smoke without fire …’ He looked at Josh suspiciously. ‘I’ve got troubles with the men and their so-called “unions”. Things have become so serious Inspector Coote’s found it necessary to call out the militia. Now a man who’s been convicted of stirring up sedition appears on the scene! I’d say that’s more than coincidence.’

‘You can say whatever you like, Strike, but don’t question my character too loudly or you’ll find yourself in a courtroom. From all I’ve heard you can do without any further trouble. Ask the militiamen to stand aside if you please, Inspector. We’re going home.’

The police inspector waved the militiamen off the road, but before the coach pulled away, he said to Josh, ‘I don’t doubt your pardon is on record, Mr Retallick,’ something in the policeman’s voice left Josh in no doubt the inspector would check his story, ‘but you spoke as though you’ve been stopped elsewhere today. Is someone trying to prevent access to the Sharptor mine?’

‘Not to my knowledge,’ Josh lied. ‘It would seem coaches are such rarities on the roads hereabouts that folks are insatiably curious.’

The police inspector expressed neither belief nor disbelief. ‘Loaded ore carts are just as unusual as carriages these days, Mr Retallick, as you’ll find out for yourself. It’s rare too for a mining man to be returning to Cornwall. Most are leaving. I trust you’ll let me know of anything you hear that might be of interest to me?’

Josh inclined his head absent-mindedly. He was thinking of the inspector’s words and looking towards the tall, Sharptor mine engine-house. A great cast-iron beam protruded through an opening high up in the building. Inside was the engine – his engine. He had built it after serving a three-year apprenticeship at the Harvey’s foundry at Hayle. Had supervised its installation on this mine. The finest engine in the county, it had been built to last a lifetime.

Incorporated in the great wooden beams which descended deep into the mine-shaft was a revolutionary ‘man-engine’, the first of its kind in the county. Nearby was the pumping-engine he had also built and installed …

Josh’s gaze shifted to the police inspector and then on to Leander Strike. ‘Mining is a peculiar business, Inspector. You need to be a gambler to invest in a mine – and only the boldest gamblers succeed.’

Josh and his father leaned side by side on the gate beside the stable at the rear of the house, saying little. There was no need for talk. Blue smoke rose lazily from the pipes clenched between the teeth of both men and each was content in the companionship of the other. The emotional reunions were over. Almost twenty years of separation had been bridged.

From where the men stood, high Bodmin Moor fell away to the Marke valley. Beyond the valley the land unfolded in a breathtakingly spectacular fashion to the wide plains extending on either side of the Tamar river. On the far horizon the western heights of Dartmoor rose, an irregular mass, from the plain. A brief, early-summer storm seemed to be following the course of the river that separated Cornwall from the rest of England. Behind the storm a soft-hued rainbow promised a crock of gold on either side of Kit Hill. The mine-embellished landmark reared a thousand feet from the valley floor to form a giant stepping-stone between the two moors.

Behind the two men Miriam called from somewhere in the house and she was answered by Anne’s high-pitched, excited voice.

‘It’s been a long time since we last shared a pouch of tobacco,’ Ben Retallick broke the silence between father and son. ‘Your ma’s had all her prayers answered by your return with Miriam and the two young maids for her to fuss over. If only young Daniel had come with you her happiness would be complete.’

‘Miriam would agree with ma, but Daniel’s a young man with a life of his own – and a good trading business between Matabeleland and the coast. He’s an important man in that part of the world. He’ll be among the richest one day, I’ve no doubt.’

‘You’ve done well too, boy. Your ma and me are proud of you.’

‘None of us need ever go hungry,’ Josh conceded. ‘That’s more than most can say, hereabouts. The mines seem to have fallen on hard times.’

‘Mining’s always been an uncertain business – as much for the men who put up the money as for those who work below grass. Matters have grown worse these past few years. Every time the price of tin and copper drops more men are laid off. Many are leaving Cornwall and going to wherever there’s work to be had. Mexico, Australia, America, South Africa … but you’ll know something of this for yourself.’

Josh nodded. He had successfully mined copper in South West Africa where many other minerals were being discovered and worked by immigrant miners.

Ben Retallick knocked out his pipe against the heel of one of his heavy mining boots. He was now sixty-one years old, but until the Sharptor mine closed down he had been one of the mine’s shift-captains, responsible for the smooth and efficient management of the mine during his tour of duty.

‘Was the Sharptor mine being worked the way it should have been, before it went out of business?’

Ben Retallick shook his head vigorously. ‘It’s been running down for years. Theophilus Strike was reluctant to hand it over to anyone else. I think he knew what that nephew of his would do. During his last years Theophilus was too old to visit us here and we couldn’t get a sensible decision from him. We haven’t had a decent engineer on the mine for years and the engines are costing twice as much to run as they should. Tom Shovell held things together while he was mine captain, but he retired a couple of years back and Theophilus wouldn’t appoint anyone to take his place. Accidents were beginning to happen and the men were becoming edgy. You can’t run a mine that way.’

‘I met Tom’s son along the road today. He seems a nice enough lad.’

Josh told his father of the miners who had brought his coach to a halt.

Ben Retallick nodded seriously as he refilled his pipe. ‘Jethro’s a good lad but he’s keeping bad company. Marcus Hooper’s been struck off the books of every mine hereabouts. We’ve no place for all this “trade union” nonsense in the mines of Cornwall. It serves no useful purpose and gives the owners another excuse for laying off men. They have reasons enough, without being handed more.’

Josh did not challenge his father’s peremptory dismissal of the aims and usefulness of the trade unions. It was a subject on which they had never been able to agree. This, at least, had not changed.

‘Is there still enough ore underground in the Sharptor mine to make running it worthwhile?’

‘Properly run it could be the best little mine in the area. It’ll never be as grand as the Phoenix once was – or make as much money as the Caradon – yet it could bring in a tidy profit. But it needs to have money spent on it – and Leander Strike’s not a man to spend money on such a venture. What with his gambling debts and a son away at some expensive school near London, he’s hard-pressed for money to live on.’

‘What’s he hoping to make from the sale of the engine and machinery?’

Ben Retallick cast a speculative glance at his son before shrugging his shoulders. ‘There are more engines than pasties on sale in Cornwall right now. I’ve heard Strike is seeking at least five hundred pounds. I’d say he has more hope than expectation. He’ll be lucky to get scrap value. Either way, it’s the end for the Sharptor mine. It won’t affect your ma or me too much. I’ve spent a lifetime burrowing in the ground like a mole. It’s time I got to know the sun. It’s the young miner I feel sorry for, especially one with a young family. He’s a choice of taking his wife and children away from everything they’ve ever known, or staying and watching them starve.’

Ben Retallick sucked his pipe noisily into life and peered at his son through the blue smoke. ‘Are all these questions leading somewhere?’

Josh nodded before straightening up away from the gate. ‘It’s possible, but let’s go up to the house and see whether Ma and Miriam have managed to get the girls to bed yet.’ He shivered suddenly. ‘It may be early summer for everyone else, but twenty years in Africa’s thinned my blood.’

Miriam’s sister, Patience, came to the house at Sharptor early the next morning. Seeing the two women standing together they were unmistakably sisters – but the similarities ended with the physical likeness. Patience was a washed-out drab woman of twenty-nine, already greyer-haired than Miriam although she was eleven years her junior. Part of the reason for this was revealed when she admitted to having lost two children before giving birth to the three she brought with her on her visit to Sharptor. The surviving children were all under five years of age. They played with the Gilmore girls in the garden, their clothes contrasting painfully. Nell and Anne were wearing new, good quality dresses, while the clothes of Miriam’s nieces would not have been accepted for cleaning-rags by a fussy woman.

Patience was aware of the contrast in the children’s clothing and she said apologetically, ‘It’s difficult keeping them decently clad with things being the way they are. I can get bal-work on the mines sometimes – but Marcus couldn’t get steady work, even when all the mines were working.’

‘Would that be Marcus Hooper?’

Josh put the question sharply and Patience looked at him quickly before shrugging her shoulders in a gesture of resignation. ‘I see you’ve heard of him already. He says he’d feel less of a man if he didn’t speak up for what he believes in. I suppose he’s right, but it don’t make things any easier for me and t

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...