- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

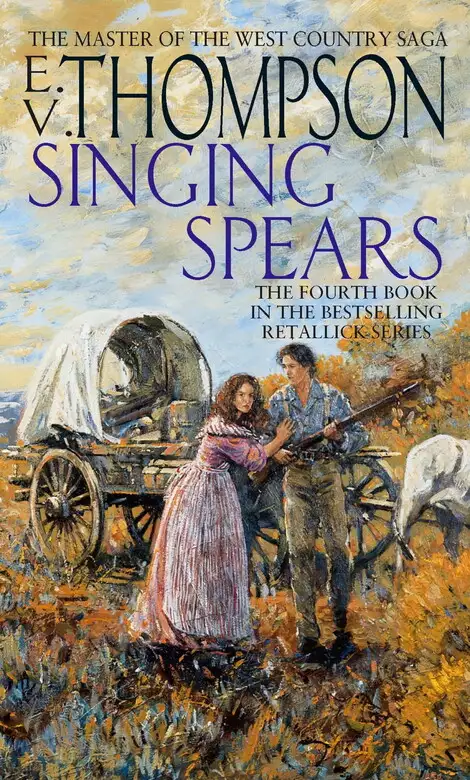

Synopsis

Daniel Retallick has grown to manhood during the years of flood tide in the chronicles of Africa. The son of Josh and Miriam Retallick, he settles with his wife and children on a homestead in a valley of Matabeleland. But the years are the 1880s, and the Matabele impis are advancing with their singing spears towards the deal-dealing Maxim guns of the white man. Daniel Retallick's loyalties, plans and dreams are about to be swept by fate into the whirlpool of history...

Release date: March 6, 2014

Publisher: Sphere

Print pages: 448

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Singing Spears

E.V. Thompson

The dust was being kicked up by the hooves of more than six thousand cattle. Pouring down the rounded slopes of a hill, they streamed towards the village, a wide, living ribbon extending for half-a-mile to the east.

The beasts were by no means prime cattle. They stumbled along with heads hanging low, red-rimmed eyes bulging from fear and exhaustion. A man could hide two fingers between their bony ribs. The cattle caught in the centre of the herd coughed and choked, swinging horned heads against the flanks of their neighbours as they breathed in more dust than air.

Yet, until a few weeks before, these scrawny animals had represented the proud wealth of a village of Manica tribesmen in their homeland around the foothills of the Inyanga mountains. Men had died for them.

Herding the cattle along their way were five hundred trotting Matabele warriors. Bedecked with ostrich feathers, they jogged along, hammering on taut hide war shields to keep the sea of cattle moving. Sunlight glinted on the gleaming, broad blades of their assegais.

The excitement in Khami was for the return of these warriors. The Matabele regiment – an ‘impi’ – had been away from its home kraal for three anxious months. Now it was almost home and the success of the foray was plain for all to see. The dust cloud of the captured cattle had been visible for hours before they came into view.

There would be a great celebration in the kraal tonight, in which all but a handful of mourning families would join. These warriors were part of the finest army in Africa and they had encountered little resistance during their campaigning. Those few tribes foolish enough to make a stand against them had been overwhelmed and slaughtered by the ruthless Matabele fighting-men.

Working in a back room of his stone-built store at the edge of the kraal, Daniel Retallick was aware of both the excitement and its cause. Twenty-six years of age now, he had been living in the royal kraal for almost five years. He had seen many victorious impis return. He knew that in addition to the cattle they would be bringing back prisoners. Captured children to be assimilated into the Matabele tribe, the girls as servants and chattels, the boys as warriors. There would be women prisoners too, to provide savage entertainment for the evening festivities.

Gritting his teeth against the images conjured up by the memories of previous ‘entertainments’, Daniel swung a wooden keg filled with gunpowder from the hard-packed dirt floor to the top of the three-tiered stack of barrels already against the stone wall.

Daniel loved the country of the Matabele, with its ancient hills and deep fertile valleys. Parched brown by the dry winter, it would erupt in a riot of flowering trees and shrubs in the rains of summer. He loved its people too and worked hard to protect them from the greed and exploitation of the English and the Boers who crowded Matabeleland’s southern borders. But Daniel recognised the shortcomings of the tribe and its despotic ruler.

In his own quiet way, Daniel had tried to wean Mzilikazi, the Matabele King, away from many of the barbaric practices that more civilised nations found unacceptable. He was succeeding – but very slowly. He feared his efforts would be overtaken by the pressing needs of those men seeking entry to the riches they believed Matabeleland to hold.

Suddenly, the sound outside the store became a great roar that echoed from the surrounding hills. Leaping on the barrels of gunpowder, Daniel peered through a high, barred window. The returning warriors and the cattle were still more than a mile away. The object of the crowd’s approbation was much closer.

Another roar, and the word ‘BAYETE!’ thundered to the sky from a thousand throats, setting a stack of tin plates rattling on a shelf in the store. ‘Bayete’ was a greeting by the people to their Paramount Chief – their King.

Daniel eased the keg of gunpowder further on to the stack before jumping to the ground. Wiping perspiration from his face with the crumpled kerchief he wore about his neck, he made his way to the front door of the store.

To cries of ‘He comes! The mountain walks among his people’, Mzilikazi was going out to meet the returning warriors, accompanied by many of his three hundred wives. Daniel realised this raid must have been something out of the ordinary.

Absolute ruler of the Matabele nation and the suzerain of a dozen lesser tribes, forty-six years had passed since Mzilikazi’s break from Shaka, the Zulu Chief. Heading northwards from Natal, Mzilikazi had taken his own people first to the Transvaal, then, later, across the Limpopo River. Here, in the hills and plains that would one day be known as Rhodesia, and later as Zimbabwe, he had welded them together as the powerful and much-feared Matabele nation.

In those days Mzilikazi had been a great chief and a warrior in the prime of life. Now, in 1868, he was almost eighty years of age and rarely left the royal enclosure. Monarch of a greatly expanded nation, heavy drinking and the cares of his warrior people had dulled his mind and taken a toll of his once-fine physique. Mzilikazi now weighed more than three hundred pounds and his gross body needed to be supported wherever he went by two of his strongest bodyguards.

But the eyes of Mzilikazi were still as keen as ever. He missed nothing. Surrounded though he was by hundreds of shouting and applauding subjects, Mzilikazi saw Daniel. Shaking himself free from his helpers, he held up a massive hand for silence. Immediately, all sound was cut off, leaving behind a stillness so unexpected that a startled flock of red-billed quelea birds took to the air in a whirring cloud from the trees in the King’s royal enclosure.

‘The day is too warm for work, trader,’ called Mzilikazi to Daniel. ‘Come! I go to meet my son, Kanje. He returns from his first raid against the Manicas.’

He waved an overweight arm in the direction of the hills, where the tail end of the cattle herd had just come into sight, ‘See? The cattle he has brought to me move across the land like locusts. He has done well.’

At Mzilikazi’s side one of his favourite younger wives beamed her pleasure at his words. She was the mother of Kanje and had worked hard for this moment. At night, in the sweaty darkness of Mzilikazi’s hut, with no one near to remind the King of her lowly status as a junior wife, she had used every wile known to woman to further the career of her only son. Sired by Mzilikazi when she was hardly thirteen years old, Kanje was but one of many hundred such royal ‘princes’. Less respectful subjects declared they were as numerous as ticks on the great royal herds. Few would even rise high enough to command one of the King’s impis. Kanje’s mother was determined that her son should profit from his royal heritage – and one day take the throne from his father.

‘Are you coming with me, trader? Would you look upon the faces of the Manica women and their spawn? My runner tells me there are many.’

Over the King’s head, Daniel could see the blood-red leaves of the royal msasa trees. He shuddered, then shook his head. ‘This is a day for your warriors and their families, Mzilikazi. I have much work to do in my store.’

The mother of Kanje glared malevolently at Daniel, incensed by what she considered to be a slight to her son.

‘You are not pleased that my warriors have won a great victory … ?’ Mzilikazi’s narrowed angrily and Daniel’s heart sank. He was probably one of the King’s most trusted friends and, in return, had a great affection for the despotic old ruler, but in recent months drink and senility had combined to make Mzilikazi dangerously unpredictable.

‘I’m happy at the success of your army, Mzilikazi,’ Daniel chose his words carefully. ‘I congratulate you on having such a brave warrior for a son – but I am a white man. Looking upon the faces of those who are soon to die gives me no pleasure.’

To Daniel’s relief, the frown lifted from Mzilikazi’s face. Daniel’s dislike of the Matabele’s more violent ways was no secret to anyone. With an expression of amusement on his face, Mzilikazi looked at Daniel speculatively.

‘Very well, trader. Stay and continue your work – but I insist that you attend the celebrations tonight. You understand me?’

The King’s eyes held Daniel’s and, sick to his stomach, Daniel could only nod his head in agreement. He knew he should have swallowed his pride and accompanied Mzilikazi to meet his son and the victorious Matabele warriors. True, there would have been isolated acts of cruelty perpetrated against the unfortunate Manica prisoners by the jeering villagers but it would be nothing compared to what he would be forced to witness at the evening’s victory celebrations. After consuming gallons of thick, kraal-brewed beer, the Matabele had no inhibitions. They would lay the dust about the celebration fires with the blood of their prisoners.

Daniel looked wearily along the valley. The first cattle of the stolen herd were now passing the low wooden shacks of the mission station that occupied an isolated position beside the main track to the kraal. There was no sign of the missionaries, but Daniel knew they would not be missing a single incident happening outside. The quill pens would be scratching the pages of their journals in a fury tonight.

There were two missionaries resident at the mission station. One was a single man, the other accompanied by his wife. Theirs was a lonely and frustrated existence. The station had been established as the result of an unguarded promise made by Mzilikazi to the veteran missionary, Robert Moffat, some years before. But giving his word to allow a mission station to be built was one thing – permitting it to function successfully was something quite different. Mzilikazi was adamant that the missionaries must not preach to his people. Summary execution was speedily imposed on any subject who appeared ready for conversion to the white man’s faith.

Daniel did not like the missionaries. Both were quarrelsome and bigotted men. Their ambition of converting the Matabele to Christianity involved sweeping away all tribal traditions and pride. Covering the people’s nakedness with western-style clothing and modelling the Matabele along the lines of Sunday-school children. In pursuit of this aim the missionaries schemed and connived to bring Europeans to the country, ignoring the dangers of such a policy. They argued that there was nothing wrong in using powder and shot to blast the benefits of The Word into the lives of Mzilikazi’s reluctant savages.

Nevertheless, in spite of his dislike for them, Daniel sympathised with the missionaries in their well-nigh impossible task. He felt a grudging admiration for their tenacity in remaining in this land, where they were so patently unwanted. Mzilikazi would not go back on the promise he had made to Moffat, but he made no secret of the fact that he would be happy if the two men abandoned the mission station and left the Matabele to the Devil – and Mzilikazi. In an attempt to achieve this aim, he insisted they perform various menial tasks for him that were beneath the dignity of his own warriors. In addition, he demanded that they grow produce for the royal household and gather wood for his fires.

The missionaries took up these additional burdens without complaint, but both men kept carefully detailed diaries of their humiliations. They hoped that future publication, together with information of the happenings in Matabeleland might arouse the passions of the British public and force the government to send an army against the Matabele and their despotic ruler. At the very least, the diaries should ensure appropriate recognition for their devotion to the Christian cause.

Thinking of the ordeal he would have to undergo that evening, Daniel wished the missionaries were men he could talk to. It would be even better if Sam Speke were in Khami … Sam and his daughter Victoria.

Sam Speke had come to Khami many years before, with Daniel. Married to a girl of the Herero tribe from South West Africa, Sam was currently on a visit with his family to his wife’s village, almost a thousand miles away.

A solid, reliable man, Sam Speke had been with Daniel’s parents when they were shipwrecked on the treacherous Skeleton Coast of South West Africa. Only three years old at the time, Daniel, with his family, had been given sanctuary by the Hereros and lived in their village for many years. Daniel’s parents had returned to England when he moved to Matabeleland, but Sam Speke came with him. He helped run the Matabele end of a remarkable trade route extending more than half the breadth of the African continent. From Mzilikazi’s capital to Whalefish Bay, on the Atlantic coast. The South West African end of the operation was looked after by Aaron Copping, Daniel’s partner. Aaron had been trading in Africa for most of his life and knew more about South West Africa than any other man alive.

Theirs was a unique trading venture. Initially, it had begun as a trading link between Whalefish Bay and the Herero heartland. Daniel had extended the route first to the Bechuanas at Lake Ngami, in the Kalahari Desert, and then to the land of the Matabele. It was a hazardous life, at best – but Daniel was the envy of a great many white adventurers. These were the men who were gradually edging the frontiers of exploration and commerce closer to Matabeleland. Only Mzilikazi’s impis, jealously guarding the rich lands over which their King claimed jurisdiction, kept them at bay.

Mzilikazi did not trust white men. He occasionally befriended certain individuals, but their numbers could be counted on the fingers of one hand and their friendship did not change his opinion of their fellows. What he learned from these select few convinced Mzilikazi beyond all doubt that if ever his country were thrown open to them the way of life of the Matabele would end forever. Mzilikazi was determined it would not come to pass in his lifetime.

As the sun sank below the summit of the range of hills to the west of Khami, the taut monkey-skin drums began to beat out from the great square in the centre of the capital. Others took up the rhythm eagerly. Soon the sound of a hundred drums echoed back and forth between the rocky crags about the town. In the centre of the square many fires sprang up and impromptu dancing began. As the dancers shuffled and swayed together in the flickering light the rapidly growing crowds about them sang and clapped in time to the music.

Daniel had hoped to arrive late at the festivities and slip away at the earliest moment without being noticed. His plans were dashed when Jandu, another of Mzilikazi’s many sons, arrived at the store with orders to escort him to the square.

‘You are to be honoured tonight, trader,’ Jandu called from the store-room as he weighed a new percussion rifle in his hands while Daniel dressed.

Daniel entered the store fastening the long sleeves of his shirt at the wrists. The mosquitoes were always worse at night and it paid to leave as little skin exposed as possible. ‘Honoured … ?’ he frowned at Jandu. ‘I’m damned if I see it that way. There’s no honour in watching unarmed women being hacked to death by young boys!’

Jandu looked very much like his father when he was amused, ‘Those young boys will one day be men – and men must be warriors. They need to know the feel of a spear entering the body of an enemy … to know which thrusts kill and which only maim. Such knowledge can make the difference between life and death to a warrior in his first battle …’

Jandu held the gun in his hands close to the spluttering animal-oil lamp and peered down the barrel. ‘Why should you care what happens to Manica women? Are they more to you than Matabele women?’

Mzilikazi’s son voiced the curiosity felt by many of the Matabele at Daniel’s apparent celibacy while living among them. It was in marked contrast to the behaviour of the few other white men who had visited Khami, seeking permission to hunt, or search for precious metals – or simply explore the land of the Matabele. Their eagerness to have a ‘slave girl’ was the subject of many ribald tribal jokes. It was rumoured that this was the real reason why so many white men wished to enter Mzilikazi’s kingdom. Indeed, before the arrival of the missionary’s wife it was believed by the Matabele that there could be no white women in Africa.

‘They are no more, and no less, than any other women,’ Daniel retorted, but Jandu had already dismissed the matter of Daniel’s taste in women from his mind. He held the rifle out towards him.

‘This is a good gun?’

‘The best. A man’s family would never go hungry if he hunted for food with one of those – but it will cost you more elephant tusks than you could collect in a full year.’

Jandu lowered the gun. With a snort of derision he tossed it carelessly aside on a pile of colourful blankets. ‘My family has never been hungry – and I hunt only with a spear. Such guns are for white men – and my father’s son, Kanje.’

Daniel looked at Jandu sharply. ‘Kanje has one of these? I’ve traded only one since they arrived – to Mzilikazi.’

‘Are such guns made only for you, trader? Kanje’s raid took him far from our home. He met with the bearded men who come on horses from the south.’

Daniel knew Jandu was talking about the Boers. Their mounted commandos often rode to the borders of Matabeleland in the hope of surprising a small group of tribesmen and stealing their cattle.

‘Kanje captured rifles from the Boers? I don’t believe it!’

Jandu allowed himself a quick smile. ‘Had Kanje captured guns from the bearded ones the Matabele would have a future King who even I would follow without question. No, trader. Kanje and twenty of his men were given the guns when the bearded ones learned he was a son of Mzilikazi.’

‘If Kanje’s accepted gifts from the Boers he’s a fool!’

Jandu nodded. ‘I see you understand the situation. Kanje does not. As you say, he is a fool – a young fool. He would rule our people, yet does not realise he has already put himself in debt to the bearded ones. If ever he becomes King they will be here, demanding the right to trade.’

Daniel remembered the look Kanje’s mother had given him earlier in the day. She was a strong-willed woman who would always influence her son. If Kanje ever ruled in his father’s place Daniel’s trading days with the Matabele would be over. The Boers would move in to take his place. Daniel knew this. So did Jandu.

‘You and I should be of one mind, trader. We both have much to lose should my brother be chosen to lead our people. You, your trade. I … my life. While I and my other brothers live we would always pose a threat to him. Unfortunately, there is little I can do to prevent Kanje having his way. I am just one of Mzilikazi’s many troublesome sons. But you have my father’s ear. You are a trusted friend. He will listen to you.’

Daniel looked at Jandu suspiciously. About thirty years of age, the Matabele was tall, even when judged by the standards of his own tribe, and he had the massive chest of his father. He also had remarkably large eyes that at first glance appeared docile, but when given a direct glance, a man felt they were burning into his very soul. Jandu had only recently returned to Khami, after serving as an Induna, or commander, of one of the King’s impis in a far-off border district.

A man of exceptional intelligence and presence, Jandu would pose a threat to the ambitions of any of Mzilikazi’s sons. Daniel hoped, for Jandu’s sake, that he had not yet attracted too much attention. But, although he was impressed by what he had seen of the other man, Daniel was reluctant to be drawn into their accession feuds.

‘You would like me to put in a good word for you, of course?’

To Daniel’s surprise, Jandu shrugged his shoulders nonchalantly, ‘There are many of my brothers who would rule better than I – but Kanje is not one of them. Under his leadership Matabeleland would become a skeleton, picked clean by the jackals who squat about our borders. I have no wish to see this happen.’

Daniel stared thoughtfully at Jandu, wondering whether all this was no more than a devious ploy by Mzilikazi himself to draw him into the intrigues of the King’s court, and so declare himself. He dismissed the idea immediately. Mzilikazi knew him better. He had always been very careful to remain aloof from the constant scheming of those who surrounded the King.

‘You need make no reply now, but do not take too long to think about what has been said here today. Mzilikazi is an old man.’

‘True – but he is still King of the Matabele, and tonight I’ve been ordered to witness Kanje’s triumph. Let’s go and get it over with.’

When Daniel arrived in the great square the victory celebrations were well under way, huge wood fires blazing furiously. The area surrounding the kraal had long since been denuded of trees and the wood had been brought from the river valley, more than two miles distant from Khami. No effort was being spared to make this a night the King’s subjects would long remember.

Around the fires beer gourds were passing from hand to hand, and mouth to mouth, the drinking accompanied by shouted bawdy jokes and loud, uninhibited laughter. Many of the men, particularly those with sons in the returning impi, had been celebrating from the moment the first warrior had been sighted on the hills beyond the capital.

In the cleared space between the fires the women danced in long, linked lines, stamping their feet, bodies newly anointed with animal fat, swaying in time to the music of the drummers.

The women of the royal harem, dressed in their finest beads and feathers were performing their own exclusive dance in the very centre of the square, watched by their happy and relaxed husband. Mzilikazi sat on a pile of cattle hides, drinking vast quantities of beer. He was far too close to the nearest fire for comfort, but seemed not to mind the glistening rivulets of perspiration that formed salt pools in the deep creases of his body.

Seeing Daniel, Mzilikazi roared for him to come and sit at his side. Daniel would have preferred to sit further away from the heat of the fire, but he dared not refuse. A gesture from the King dismissed Jandu, and Daniel chose a place on the heaped cow hides, accepting the gourd of beer that was quickly passed to him by one of Mzilikazi’s wives.

The beer, brewed and drunk by the Matabele, had the consistency of a well-watered porridge. It smelled sour but the taste was not unpleasant. Under the watchful eyes of Mzilikazi, Daniel took a deep draught before setting the gourd down on the ground beside him.

Resting a heavy hand briefly on Daniel’s shoulder, the Matabele King beamed at him benignly. ‘I am pleased to see you are still one of us, trader,’ he boomed. ‘Now you will hear of my son’s first raid.’

Clapping his hands, Mzilikazi ordered the dancers from the square.

As the women hurried to find space on the ground behind their menfolk, the crowd’s excitement increased in volume, drowning the complaining lowing of the captured cattle, penned within the royal cattle kraal, just beyond the village.

Another signal from Mzilikazi, then he sprawled back on his hide throne to enjoy a re-enactment of the raid on the Manicas.

First to take the stage was the King’s ‘Inganga’ – his ‘witch-doctor’. Accompanied by two assistants, he wore a hideous mask and a tall headdress of fur and feathers and made a frightening giant figure in the capricious light from the fire. After performing a series of incredible leaps and contortions that had the appreciative crowd gasping in awe, the Inganga stood in front of Mzilikazi and scattered a variety of powdered potions to the four winds. Then he began extolling the virtues of the King, reminding his subjects of past victories. As each one was mentioned the great crowd let out a sigh of appreciation.

When he felt enough had been said to satisfy the King’s vanity, the Inganga began telling his listeners of the success of Kanje’s raid in the unknown lands of the Manica tribes. He reminded King and the subjects that it was he, the Inganga, who had sent the raiding-party on its way protected by some of his most powerful ‘medicine’.

‘Powerful it may have been,’ interrupted the King. ‘But some faces were missing from the returning impi. How many of my warriors died?’

The Inganga turned to the Induna of the impi, who fell to his knees in front of his King.

‘Seven, Kumalo.’ Kumalo meant literally ‘Majesty’.

‘Name them.’

The Induna called out seven names. As each rolled off his tongue there was a groan from the listening crowd, and a wail from the women of the dead warrior’s family.

‘How did they die?’ asked the King, when the names were known.

‘They died bravely, Kumalo. They were truly Matabele warriors.’

Mzilikazi nodded his satisfaction, ‘Each elder son, or father of the dead men is to be given ten captured cattle.’

There was a sigh of approval from the crowd. It was a generous gesture.

Next, the Inganga gave details of the number of their enemies killed, cattle gained for the Matabele, and the number of prisoners secured.

As the Inganga spoke, evidence of his statistics were produced for the benefit of his audience. A dozen cattle, terrified by the din about them, were dragged into the square and Mzilikazi immediately ordered them to be killed and roasted over the fires for his people. Next came the unfortunate prisoners, women and boys, herded into the firelight to the derisive jeers of the spectators. Many of the captured women fell to their knees in front of Mzilikazi, begging him to spare their lives. The children who were to be assimilated into the tribe clung to their mothers, too bewildered to understand what was about to happen. After no more than a brief glance in their direction, Mzilikazi dismissed them from his presence.

Next, the Inganga’s assistants ran towards Mzilikazi carrying two bulging hide bags. As the bags were upturned before the King a dozen dust-smeared heads thudded to the ground and a great roar of approval went up from the crowd.

Daniel had been prepared for this display of barbarism. He had witnessed such incidents before – but he was not expecting Mzilikazi’s next move.

The Inganga peered at each head in turn, finally selecting one topped with short, curly grey hair. Carrying it to the King, he handed over the gruesome object, declaring it to be the head of the Chief of the Manica tribe.

Mzilikazi took the head and held it up before him, studying the features. Suddenly, he tossed the head through the air towards Daniel who caught it in an involuntary action.

‘There, trader. Does he look as noble as a Matabele?’

Aware of the laughter of the watching Matabele, Daniel shrugged, carefully concealing the revulsion he felt. ‘He looks like any other man. No doubt he was proud of his tribe, and honoured his ancestors.’

Daniel placed the gruesome trophy next to the King. Mzilikazi hurriedly pushed it to the ground and ordered the main event of the evening to begin.

Daniel had played upon the King’s own superstitious beliefs. The Matabele were taught that if a man honoured his ancestors throughout his own life, his own spirit would be welcomed by them after death. These ancestral spirits would not be pleased with any mortal who made their task more difficult by separating head from body.

The Inganga’s two assistants removed the heads of the dead Manica warriors and now the victorious Matabele impi marched proudly to the firelit square, applauded loudly by relatives and friends. Dressed in their warrior feathers and carrying tall, hide shields and broad-bladed assegais, they spread across the square, assuming the extended-horn battle formation of an attacking Matabele impi. This was the Zulu manoeuvre that had struck terror in the hearts of enemies from Natal to the Zambezi River.

Chanting slogans and thudding their feet heavily to the ground with each step, the impi advanced across the square until it was within a few paces of Mzilikazi. Then, with a great shout of ‘Bayete!’ it broke ranks and the warriors moved off to one side.

Their Induna stepped forward and began giving Mzilikazi a lurid account of the raid. He was a good narrator and the crowd remained absolutely silent, straining to hear the Induna’s every word. As each man was mentioned, he stepped forward and re-enacted the incident that had provoked such an honour, each stroke of his assegai signifying the death of an enemy at his hands.

Finally it was the turn of Kanje to step forward and impress the King with a display of his prowess. Glistening muscles rippling, the junior son sprang from the ranks of his fellow warriors, scornfully discarding his shield. Brandishing an assegai in his right hand and a rifle in his left, he performed well. To the accompaniment of the Induna’s recital, he vividly relived the highlights of his great adventure. The watching subjects held their breath as Kanje crept from the broken rocks of a Manica hillside towards an unsuspecting sentry. They gasped as he fought w

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...