- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

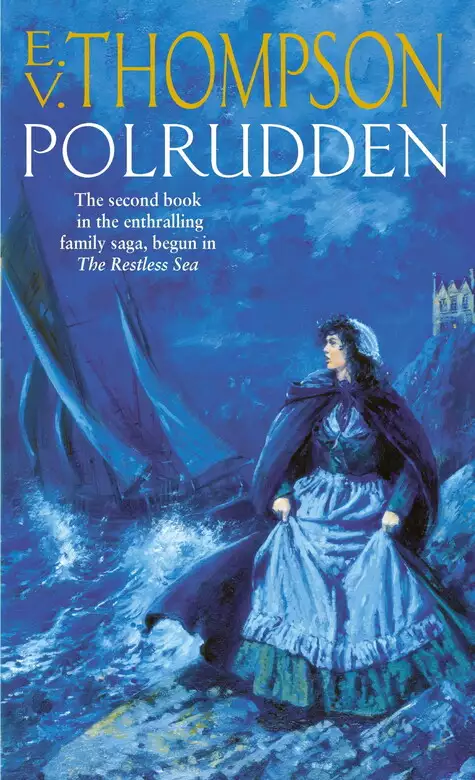

Synopsis

On a wild stormy night in 1813, Nathan Jago, drift fisherman, ex-prizefighter and lord of the manor of Polrudden, rescues a young boy from a drowning mother's arms as a French ship founders on the jagged Cornish rocks. It is an act that will profoundly affect his destiny. Despite hard times, Nathan and his wife Amy adopt Jean-Paul and bring him up with their own son. Nathan considers a return to the ring in the struggle to make a living and keep the ancient house in the family. But events conspire to involve him in a royalist intrigue that eventually leads to Paris - where a beautiful marquise and a dashing count sow the seeds both of tragedy and renewed hope...

Release date: February 13, 2014

Publisher: Sphere

Print pages: 448

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Polrudden

E.V. Thompson

Once inside the great high-roofed barn, the villagers peeled off waterproof coats and agreed this was the roughest September weather anyone there could remember.

However, it was not long before the wind and rain rattling the tiles high above their heads were quickly forgotten as the newcomers accepted tankards of ale and took in the scene about them.

They collected in small, excited groups in the centre of the ancient barn, surrounded by long, rough-planked trestle-tables that sagged beneath the weight of more food than the noisy, wide-eyed Pentuan children had ever seen.

There were many fish dishes, of course, for this was a fishing community: marinated pilchards; ‘fumadoes’, the smoked fish so loved by the Spanish and Portuguese peasants; fat mackerel baked in bay leaves; and ‘starry-gazy pie’ containing whole cooked pilchards, their heads protruding through the centre of the pastry, eyes gazing balefully and sightlessly at the high rafters above.

But there was more than fish on offer today. Each table bore at least one fat cooked goose, its plump legs angled indecently in the air. There were rabbits, pasties, hams, pigs’ heads, and loaves of barley bread stacked like quarry waste in great baskets. For the children there was hobbin pudding, jam tarts, cakes and gingerbread.

Nathan Jago stood at one end of the great barn, where a pit had been dug in the floor and filled with a charcoal fire, the smoke disappearing through a hole in the cob-and-stone wall. Over the fire a whole bullock rotated on an iron spit, turned by a team of red-faced, perspiring men. Their colour owed as much to the vast quantity of ale they were consuming as to heat from the fire.

‘You’ve done the villagers proud today, Nathan. It does my heart good to see so many happy faces.’

Nathan turned to where his father was running a spotted kerchief about the damp neckband of his frayed collar. In his other hand, Josiah Jago held a preacher’s hat, its wide felt brim limp and wet. Beside him, ill at ease in the manner of a young man in unfamiliar surroundings, stood the Reverend Damian Roach. Sent to Josiah Jago by the Methodist Society to gain experience ‘in the field’, the close-knit Cornish community in which he found himself.

Nodding to the younger man, Nathan replied to his father: ‘They’ve had little cause for merry-making these past few years. The pilchards haven’t run in any numbers for nigh on two years – and when they have we’ve been unable to get good French salt to cure them, thanks to this damned war. Add to this the crippling cost of corn…! It’s a wonder half of Cornwall hasn’t starved to death.’

‘More than half are starving,’ replied Josiah Jago unhappily. ‘All tithe-holders aren’t as generous as you. They demand their dues, even though it means taking food from the mouths of children. They’ll have a hard time explaining their actions to the Lord when the Day of Judgement comes. In Matthew eighteen, verse six, it’s written: “But whoso shall offend one of these little ones —”’

‘I don’t doubt you’re right,’ Nathan interrupted hurriedly. He knew from experience that his father would launch into a lengthy sermon given the slightest provocation. ‘But everyone is waiting for you to say a prayer, so we can begin the celebrations. I’ll call for quiet.’

As Nathan made himself heard above the babble of voices, the conversations faltered and died, erupting again in a sibilant ‘Sh!’ when some of the children continued to play a noisy game of tag at the end of the barn farthest from the spitted steer.

‘Friends,’ – Preacher Jago’s voice was quite capable of carrying above such minor interruptions – ‘I have been asked to call on Our Lord to bless this feast today. Before I do, I know you’ll want to join with me in giving thanks for the joyful events that have occasioned such a splendid repast. It also gives me the opportunity of introducing the Reverend Damian Roach to those of you who have not yet met him. Recently ordained in the Established Church, he has decided to devote his future to the Methodist movement and has come here to learn the ways of a Cornish circuit.’

After a brief outburst of polite applause had subsided, Josiah Jago continued: ‘But the main reason for our celebration is, of course, the return to us of our brethren – Matthew Clarke, Jonathan Hunkin, Hannibal Truscott, Lewis Dart and Samson Harry. Taken by the enemy whilst peaceably reaping the harvest of the sea within sight of their own homes, they remained in French hands for five years until they and seven Mevagissey fishermen were released by the victorious army of our noble Lord Wellington in far-off Spain.’

As Preacher Jago paused to cast a glance over the villagers gathered about him, a gust of wind rattled the slates on the high roof of the barn and one or two faces looked up anxiously.

Preacher Jago was unaware of the momentary diversion as he picked out the faces of the five rescued men among the celebrating villagers. ‘We thank Thee for the deliverance of our brethren, O Lord, and pray this war may soon come to an end and all those who fight for king and country return safely to us once again.’

The murmured ‘Amen’ from the assembled villagers was followed quickly by Nathan.

‘Thank you, Father. Now, everyone, get something to eat. Don’t stint yourselves. There’s plenty of food and drink. I want nothing left behind to feed the mice and rats.’

Preacher Jago had intended saying much more, as the villagers knew, and they were smiling as they surged forward, heading for the heavily laden tables.

After only a moment’s hesitation, Preacher Jago followed in the wake of the villagers. A dedicated, hardworking preacher, he lived as frugally as the poorest fisherman there. Any money that came into his hands went immediately into the ever-empty coffers of the Methodist Church.

As Nathan watched the Pentuan villagers heaping food upon their plates, a small, slight girl moved to his side, her fingers finding his hand. It was Amy, his wife. Her gaze upon the busy scene about the tables, she said: ‘I didn’t realise there were so many villagers. Do you think there will be enough food to go round?’

Nathan squeezed her fingers affectionately. ‘There has to be. I’ve already spent enough money to keep the St Austell poorhouse going for a full year.’

St Austell was the market-town, four miles away. There had been a recent slump in the ore from the many tin mines to the north of the town. The poorhouse, already overfull with the widows and orphans of Wellington’s soldiers, was placing a severe strain on the parish.

‘I’m sorry, Nathan. I know this celebration was my idea, but I didn’t realise how many people would come. Has it cost too much?’

‘We’ll survive – if the pilchards appear off the coast soon. We’ve got three boats operating out of Portgiskey, yet they haven’t caught enough to pay one crew’s wages this year.’ Nathan squeezed Amy’s hand again. ‘One thing is certain, we’re giving everyone a meal they’ll talk about for years to come.’

Further conversation became impossible as villagers returned from the tables with laden plates and drew Nathan and Amy into conversation.

Nathan had moved on to supervise the distribution of meat from the spit-roasted bullock when one of the maids from the house entered the barn. A coat was raised above her head to protect her from the rain. Pausing in the doorway, her eyes searched the crowd. When she saw Nathan, she hurried to him.

‘Begging your pardon, Master. I just went up to my room over in the house – it’s in the attic. While I was there I… I saw something. When I told Cook, she said I must hurry across here and tell you straightaway.’

Nathan nodded, slightly impatient. ‘What was it? Has the storm damaged the roof? Is rain coming in? If it is, you’d best go and find —’

‘ ’Twasn’t the roof, Master. It were a ship.’

Nathan looked from the girl to the stormy-grey sky, visible through the high window-slits of the barn.

‘You saw a ship, in this weather? You can hardly see the cliff-edge from the house.’

‘No, Master, but it’s squally, see. Belts of rain coming in across the bay. In between it’s a bit clearer. That’s when I saw this ship. It was a big one, with three masts. It were leaning right over in the water, heading north towards Black Head.’

Nathan’s scepticism left him. The girl’s description had been too detailed for the vessel to be a figment of her imagination. He would need to take some action. Any ship heading northwards and close enough to shore to be seen in this light would be unable to avoid Black Head, the high promontory jutting out into the sea, half a mile away.

‘How long ago was this?’

‘Not more than five minutes, Master – ten at the most.’

Nathan looked at the men standing about him. All were dressed in their Sunday clothes. They would not relish tramping through the mud of a cliff-top path in search of a ship that might or might not be about to go aground on Black Head.

Amy was at the far end of the large tithe-barn. Nathan decided there was no need to tell her what he was about to do. To the housemaid he said: ‘Tell Will Hodge to saddle two horses and bundle up a few pitch torches in an oilskin while I change. We’ll try heading the boat off – if it’s still afloat.’ Will Hodge was the Polrudden groom.

Preacher Jago had heard the exchange and he said: ‘I’ll come with you…’

‘No. You stay and keep everyone happy. Tell Amy where I’ve gone only if she asks. There’s no need for her to worry unnecessarily. If I’m not back in the hour, send someone out to find me.’

Ten minutes later Nathan and Will Hodge were riding in single file along the cliff-top. The weather was just as the maid had described it. Most of the time driving rain and mist reduced visibility to no more than forty or fifty yards. Then the rain would ease off, and for a few minutes it was possible to see out across the white-crested waves for a few hundred yards.

During one such lull, Nathan pulled his horse to a startled halt. Behind him Will Hodge was forced to do the same.

Pointing out to sea, Nathan cried: ‘There’s something out there, Will. Can you see what it is?’

The groom peered out across the bay, but the rain had closed in again and approaching dusk restricted visibility still further.

Will Hodge ran a hand across his wet face. ‘I can’t see anything.’

‘There. Now!’

This time Will Hodge saw what Nathan had seen before. ‘It’s a ship, right enough, but it’s heading south.’

‘And far too close to shore. They’ll never clear Chapel Point in this sea.’

Mevagissey Bay curved in a shallow crescent, with Black Head to the north and Chapel Point to the south. A safe anchorage, favoured by ships when the prevailing westerly winds were blowing, it was an inescapable trap for a sailing vessel caught in an easterly storm.

Nathan also observed something that had escaped the attention of the groom, but he said nothing. Flying from the masthead of the doomed ship was a tricolour flag of red, white and blue. The ship battling against the storm was a French vessel.

‘Their only hope is to put in to Pentuan,’ shouted Nathan above the noise of the wind. Pointing to the wrapped torches, he added: ‘If we can light these, we might be able to guide the ship in.’

Will Hodge shook his head doubtfully, but he, too, realised this was probably the only chance the ship had of reaching safety.

The two men were halfway to Pentuan across the cliff-top when Nathan heard Will Hodge’s shout above the noise of the storm.

The groom was pointing out to sea, his face registering disbelief. Following the direction of Will Hodge’s startled gaze, Nathan saw the ship again – but now she was heading straight towards them. Steering towards the cliffs!

Nathan realised immediately the reason for the vessel’s extraordinary new course. There was a quarry dug deep into the cliff below Polrudden, with a small quay from which stone was loaded directly into ships. Over the centuries the quarry workings had eaten farther and farther into the cliffs. It would be easy for a stranger to the coast to mistake the quarry for a small harbour. By the time the ship’s captain realised his mistake it would be too late. The channel to the quarry quay was narrow and angled. It required a coxswain with detailed knowledge of the coast to bring a ship in, even in the most favourable conditions. In weather like this such an attempt would be suicidal for a stranger.

At that moment the ship made an alteration in course, and Nathan noticed the sluggish manner in which the vessel responded. The French ship was so low in the water that the deck was almost awash. Nathan realised the ship was taking water. The captain had to take a desperate chance. He was in charge of a sinking vessel.

‘Give me the torches and ride to Polrudden. Get all the men you can – and ropes.’

Will Hodge handed over the oilskin-wrapped bundle. ‘What are you going to do?’ He shouted the words, but a fresh gust of wind off the sea snatched them away and he had to repeat them.

‘I’m going down to the quarry to do whatever I can. Hurry!’

Nathan left his horse at the top of the steep path that led down the cliff to the quarry. In this weather it would be safer going down on foot. He could not see the ship now, but knew it must be close to the narrow quarry channel.

On the quay was a small disused checking-house. Although derelict, it provided shelter from the wind, and Nathan crouched here and set about lighting the pitch-impregnated torches. It was difficult. Water from Nathan’s saturated coat constantly threatened to soak the tinder in the box containing flint and steel. Not until Nathan peeled off his dripping coat was he able to raise a flame from the tinder. Cursing impatiently, he eventually managed to transfer the flame to the damp torch. When he felt the torch was burning sufficiently strongly to compete with rain and wind, Nathan ran to the seaward end of the small quay.

The French vessel was well off course for the channel. Hoping desperately that someone on board had a glass trained on the shore, Nathan began signalling with the torch, trying to convey the message that the ship needed to steer to the right of its present course.

Much to his relief, the ship heeled over slowly. Wallowing heavily in the rough water, she pursued a sluggish course towards the hazardous channel.

It was the beginning of the longest twenty minutes of Nathan’s life. Half-filled with water, the French ship answered reluctantly to the hard-working helmsman. On one occasion it failed to respond at all, but the French captain was a skilful and resourceful sailor. Just when it seemed the ship would be dashed upon the smooth black rocks, an anchor was thrown overboard from the stern. It held for long enough to enable the ship to be swung away from disaster in the manner of a giant pendulum. Its purpose served, the anchor was cut free and the ship surged forward, caught in the grip of wind and tide.

Twice more the same device was used to bring the ship round the worse angles in the narrow channel, and Nathan began to believe the impossible might be achieved.

By now the first breathless villagers had reached the cliffside quarry from Polrudden. They watched with mixed feelings as Nathan worked to guide the ship to safety. Not all the fishermen joined Preacher Jago in his prayers for the safety of their fellow-men. For many, a shipwreck on this stretch of coastline meant the chance of plunder. It was ‘the Lord’s bounty’, enjoyed by the fishing communities of Cornwall through the centuries.

Yet even those who disagreed with Nathan’s attempt to save the ship kept their thoughts to themselves – until Samson Harry spotted the tricolour flying at the ship’s masthead.

‘Dammit! That’s a French ship out there! Why are you trying to save her? She belongs to the King’s enemies.’

‘Do you see any gun-ports, Samson? It’s a merchantman, manned by ordinary seamen – men like most of us here.’

‘I suffered in French hands for five long years. I’ll not lift a finger to save any one of ’em. Let ’em all die.’

Samson Harry’s face was suffused with an anger fuelled by the drinks he had consumed at Polrudden. Five years as a French prisoner-of-war had left him unused to strong English ale. He took a step forward, as though to snatch the spluttering torch from Nathan’s grasp, but one look at Nathan’s face quickly brought him to his senses. Nathan Jago was not a man with whom to tangle.

‘Damn you, Jago ! It’s well known you’ve made a fortune from trading with the French while we’ve been fighting a war with them.’

This time the expression on Nathan’s face caused Samson Harry to take an involuntary pace backwards, but Nathan had more important things to do than quarrel with a returned prisoner-of-war. His attention returned to the ship and he signalled for the helmsman to keep the ship farther to the north of the narrow quarry opening. When he spoke again to Samson Harry it was done without shifting his gaze from the storm-bound vessel.

‘I’ve done my share of fighting the French, as well you know, Samson. If you’re not satisfied with what I’m doing, you can take it up with me when you’re sober, if you’ve a mind. But speak to your wife first. If it hadn’t been for French salt, shipped in during the night hours, there would have been no work for her in my fish-cellar. You’d have come home to find your wife in the poorhouse and your boys packed off in a man-o’-war by the poorhouse master.’

A moment later, Samson Harry was forgotten as the French vessel began to drift dangerously off course, all steering gone as the high cliffs played tricks with the wind. The ship swung diagonally across the channel, and now the waves had the vessel in their grip.

The most mercenary of the watchers on shore gasped in horror as the French ship was flung upon rocks as unyielding as a bulldog’s teeth. The rocks held fast as successive waves pounded the stricken vessel. Their grip was broken only when a huge wave combined with the frenzied wind to lift the vessel and turn her upon her side.

As the rocks dug deep into the ship’s flanks, timbers screeched in anguish. At that moment the villagers of Pentuan knew they were not to be cheated of their storm-driven bounty.

Only minutes after the ship had been thrown on her beam, half a dozen villagers were spoiling their Sunday clothes in the water at the edge of the quarry. Wading knee-deep, they jostled one another in a bid to be the first to reach a small wooden chest, washed from the clutches of one of the unfortunates who had been standing on deck when disaster struck the French ship L’Emir.

Rising above the din of the storm and the eager shouts of the Pentuan villagers, Nathan now heard a new sound. It was the terror-stricken cries of men brought face to face with death. Yet it was not only sailors who had been shipwrecked on board L’Emir. She was a passenger-carrying vessel, and soon Nathan could hear the shrill screams of women and children.

In the failing light, Nathan watched as passengers who had managed to fight their way to a hatchway began spilling out into the sea. He looked on helplessly as a loudly screaming woman rose high on a wave, midway between ship and sea, her skirts floating in a wide circle about her. At the mercy of the storm, she was given a cruel glimpse of the shore and safety, before being drawn out to sea, to vanish beneath the angry grey waters.

More and more figures began to appear at the hatchways. Confronted by glistening black rocks and frothing, bubbling water, they tried to draw back, only to be pushed headlong by those who came behind.

Will Hodge and two young village men hurried down the path to the quarry, long ropes slung over their shoulders.

‘Quick, over here.’

Nathan took the rope from Will Hodge and hurled one end to a floating woman. Caught in the waters inside the quarry workings, she was being swept to and fro by the movement of the sea. She succeeded in catching the rope at Nathan’s second throw, and he dragged her to the quay. From here she was hauled to safety by Will Hodge, helped by Preacher Josiah Jago.

‘We’ll need to get a rope to the ship,’ Nathan shouted.

It was raining hard again now, stinging Nathan’s face as he stared out to sea. Only Will Hodge heard him as the Polrudden groom struggled up the quay steps, supporting the rescued woman.

The majority of the Pentuan villagers were at the water’s edge, some of them wading waist-deep to reach the flotsam drifting from the ship. One of the large hatch-covers had split open, and cargo of every description was drifting ashore.

Survivors from the doomed vessel were also struggling to the shore now. Nathan saw one, bleeding profusely from a gash on his forehead, actually knocked back into the sea by a fisherman eager to reach a leather sea-chest floating low in the water.

‘You’ll get no help from anyone tonight,’ commented Will Hodge grimly. ‘The pickings are too rich.’

Women from the village had reached the sea-edge quarry now and were behaving with even less restraint than their menfolk. A roll of silk had floated ashore, and four women fought over ownership. As fists flew and voices were raised in anger, they used language as foul as any uttered by their fisherman husbands.

Nathan looked to where the ship was now little more than a wildly pitching outline against the storm-darkened sky. For every passenger and crewman who had taken to the water, there were two clinging to the hull and tangled rigging, crying pitifully for help.

Nathan arrived at a sudden decision. Stripping off his coat and boots, he knotted one end of a rope about his waist, ignoring the alarmed protests of his father.

‘Fasten the other end of the rope to something strong – one of the berthing-rings will do – then help Will to pay out the rope slowly behind me as I swim out to the ship.’

Nathan plunged into the water, his dive taking him well beneath the surface. The sudden silence as the water closed over him came as more of a shock than did the icy cold. He rose to the surface – only to be dragged down again by a desperately struggling woman. Gasping and choking, she clung to him in a frantic bid to save herself from drowning.

It needed considerable strength to break free from her grip and push her towards the quay. When hands reached out to pull the woman to safety, Nathan struck out once more for the wrecked vessel.

He was a strong man and a powerful swimmer, but he needed every ounce of his strength to battle his way clear of the quarry. More than once he narrowly avoided being dashed against the rocks by the waves that swept in from the bay. Then, when he was still ten yards from the ship, the swell lifted him and flung him into a tangle of rigging.

Scrambling upwards, Nathan finally sat on the side of the heaving vessel. The noise out here was fearsome as the ship rose and fell on the rocks, her timbers screeching a protest to the wind.

Nathan worked his way aft, passing many survivors who clung helplessly to the wreck, shrieking for help.

The mainmast had been snapped off about ten feet above the deck, but enough of the boom remained to enable him to secure the rope. Providing those on shore took up the slack without allowing the rope to tauten to breaking-point, many lives could now be saved. All that remained was to let the panic-stricken survivors know there was now a life-saving link with the shore.

Communicating his message proved far more difficult than Nathan had anticipated. Most of the passengers approached by Nathan continued to wail hysterically. Only one woman seemed to understand what he was saying, but she refused point-blank to leave her uncertain sanctuary amidst a tangle of sodden rigging and canvas.

Then Nathan found a Frenchman wedged in the after passenger hatchway, braced against the constant rise and fall of the trapped ship. The Frenchman was helping passengers to make their way to places where they might cling on, in hopeful anticipation of eventual rescue.

Nathan repeated his message twice before the man showed signs of understanding. Gripping Nathan’s arm in sudden hope, the Frenchman called inside the hatch before easing himself from his uncomfortable position and motioning for Nathan to take his place.

Putting his mouth close to Nathan’s ear, he shouted in excellent English: ‘Direct them to the rope. I will be there to help them.’ Gripping Nathan’s arm once more, he added: ‘God Bless you, Englishman.’

The Frenchman disappeared into the near-darkness, collecting survivors along the way, confidently calling on his compatriots to follow him to safety.

Nathan remained at the hatchway, helping more than a dozen men and women through the hatch, until he was told there were no more passengers left inside.

Gratefully, Nathan eased his aching limbs from the uncomfortable position he had been forced to adopt. He was about to follow the others, when he thought he heard a cry from inside the ship.

He could not be certain; there was too much noise about him. He had almost convinced himself he had been mistaken when he heard the sound once again. This time there could be no doubt. It was the cry of a small child.

The ship was trapped firmly on the rocks now, with the tide still rising and the storm showing no sign of abating. There was a very real danger that the ship would roll over. If it did, it would either drop back and sink in the deeper waters of the bay, or be smashed to pieces at the foot of the cliffs.

Clinging to the edge of the hatchway, Nathan climbed inside the solid darkness of the ship. In here he was away from the howling of the wind and the sound of the sea crashing against miles of cliff-face. There was noise, of course – a constant battering of the sea against the hulk, and the screeching of tortured timbers – but he could hear the crying more clearly now. It was coming from farther along the side-tilted passageway.

Nathan made his way towards the sound. Crouching low in the narrow corridor, his greatest danger lay in falling inside one of the cabins where heavy furniture was being flung from side to side in the swirling water.

He was halfway along the passageway when the ship unexpectedly shifted position. Rising on a great wave, she crashed back on the rocks, sliding between two of the largest. The movement brought the ship almost upright once more. It also caused a surge of water along the passageway, strong enough to bowl Nathan over. He regained his feet quickly, but the water now lapped about his waist. He knew there must be a great hole torn in the ship’s bottom. It was necessary to find the child quickly and leave the ship.

The cries had stopped, but Nathan splashed on. If the child had fallen in the water, it might be drowning at this very moment.

Suddenly, he heard the whimpering of a terrified child. There was another sound, too: the comforting murmur of a woman’s voice. They came from inside a cabin close to Nathan. At that moment the ship crunched against the rocks and Nathan fell against the edge of a door-frame, cursing involuntarily.

There was an immediate response from inside the cabin. A woman’s voice spoke in rapid French, unintelligible to Nathan, and he cut the tirade short.

‘Do you understand English?’

After the briefest hesitation, a soft, heavily accented voice answered.

‘Yes… A little.’

There was no time to ask the woman why she had not made her way to the hatchway with the other passengers. ‘You’ve got to get out of here quickly. The ship is likely to go down at any moment.’

‘Then, take my son. Go.’

A child was thrust into Nathan’s arms. It clung to him, at the same time setting up a frightened howl at being parted from its mother so abruptly.

Nathan settled the child in one arm and reached out in the darkness for the woman. ‘We’ll all go together. There’s nothing to be frightened of.’

‘I am not frightened. I… My leg. It is broken. Take my son and leave, I beg you.’

The ship shuddered beneath the weight of yet another wave, and Nathan felt the bow of the ship drop.

‘You’ll come, too.’ Reaching out, he found the woman slumped in a corner of the cabin, wedged between the bulkhead and a wooden deck-support. ‘Hold me, I’ll float you to the hatchway.’

It was doubtful whether the woman fully understood, but there was no time to explain. When she made no move, Nathan took her arm and pulled her towards him.

She cried out in pain, but instinctively clutched at him for support.

‘Good. Now, float… Float!’

As he shouted the last word, he dragged her to the doorway, ignoring her cries. The child began to wail with renewed terror, but once in the passageway the woman seemed to understand what was required of her and she stopped struggling. Clinging tightly to Nathan’s shirt, occasionally twisting painfully in the water as the seas buffeted the ship, she stayed with him.

The water had risen to chest height now. Once, when Nathan was thrown off balance by a more violent movement than usual, the woman lost her grip on his shirt. She flailed helplessly about in the water until he was able to pull her back to him.

At the hatchway steps he pulled the woman up behind him, gritting his teeth against her cries of pain. Not until her head and upper body were clear of the hatchway did he allow her a brief respite.

‘Please… leave me and take my son to safety.’ Her voice gave a clear indication of the great pain she felt.

‘It’s not much farther now. The worst is over.’

‘Then, take him first. Come back for me.’

Nathan hesitated for only a few moments. She was right. There was no way he could carry both the boy and his mother to shore together. But leaving her might be condemning her to certain death.

‘All right – but you hold on here. I will be back for you. Do you understand?’

‘I understand. May God go with you. Please… What is your name?’

‘Jago. Nathan Jago.’

‘My son is Jean-Paul Duvernet. You will remember?’

‘I will – but I want you around to remind me. Stay exactly where you are until I return.’

‘Take care of my son, Nathan Jago. Take very good care of him, I beg you…’

At the splintered mainmast Nathan found the Frenchman whose place he had taken at the hatchway. Putting his mouth to Nathan’s ear, the Frenchman shouted: ‘I have made a sling. It is only a loop about the rope you brought to the ship, but it is successful. People are reaching shore alive…’

The ship gave a sudden lurch and heeled over at least forty-five degrees. Thrusting the boy into the Frenchman’s arms, Nathan shouted above the wind: ‘Take him ashore. I’m going back for his mother. She’s broken a leg.’

As Nathan made his way back to the hatchway, the ship shifted yet again. This time he thought the vessel was going right over, but at the last moment she grounded on the rocks and held. However, she now lay completely on her side again, and the last few yards to the hatchway required the agility of a monkey.

The woman was nowhere to be found. Nathan searched the surrounding rigging and called into the darkness again and again, but there was no reply. After a moment’s hesitation, he climbed through the hatchway. Water completely filled the cabins on one side of the ship now, leaving only a couple of feet of space in the passageway. There was no sign of the woman, and Nathan’s voice was lost in the sound of protesting timbers.

Another movement of the ship reminded Nathan of his own danger. He clambered out through the hatchway once more.

Carried on the wind, he imagined he heard the soft voice calling to him once more.

‘Take care of my son, Nathan Jago. Take very good care of him, I beg you…’

The following morning it was as though the storm and the wrecking of the French ship L’Emir had never happened. The sky was the colour of soft washed canvas and the sea lay low, ashamed of its recent anger. In Pentuan village the wind picked desultorily at leaves and broken twigs strewn in profusion about the cottages flanking the square.

The flotsam choking the waters of the tiny quarry harbour had long been gathered in, but boats from Pentuan were trawling the waters about the sunken ship in search of gleanings.

On land, boys and men scoured the shoreline. Their harvest was a grim one. Seventeen bodies were carried to the small Methodist chapel in Pentuan to await burial. Seven more would be found before the day ended. Others would be discovered on the beaches of nearby Cornish parishes and buried without record below high-water mark. Times were hard for the living in Cornwall. No one wasted effort on unknown dead – especially French dead.

Grieving friends and relatives who had survived the wreck sat about the chapel burial-ground. Their earlier noisy grief had given way to a sense of loss, accentuated by the knowledge they were in a country with which France was at war.

One of the bodies lying in the chapel in Pentuan was that of Marie-Louise Duvernet. She had been identified by the Frenchman who had been responsible, with Nathan, for saving many lives the previous night.

Dark-skinned, Marie-Louise Duvernet possessed a beauty that death had not yet been able to steal from her. When Nathan commented on this, the Frenchman smiled wryly.

‘In Martinique men fought duels for a smile from Marie-Louise. Yet many eyebrows were raised when Captain Charles Duvernet married her. One takes a – a “lady of colour”? – for a mistress, not as a wife. But how is her son? He is still at your house?’

‘Yes. This morning he seems far more interested in my own son’s rocking-horse than in what’s happened.’

‘Good. He will have a lifetime to feel sad at the loss of his mother.’

The Frenchman looke. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...