- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

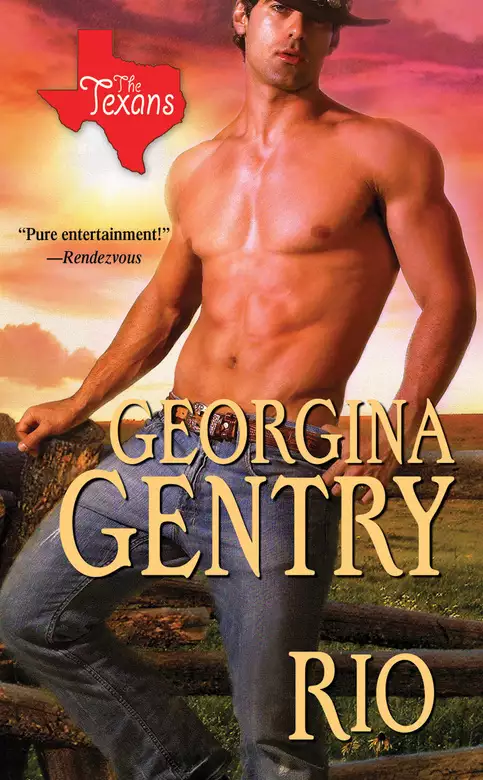

He's a man who burns as hot and free as a wildfire--and where love is concerned, he's twice as dangerous. . .

Rio

Rio Kelly knows what he wants when he sees it--and he wants the ebony-haired, fair-skinned beauty with the extraordinary blue eyes, Turquoise Sanchez. But in the battle for her love, this bold vaquero is competing with a Texas senator who's used to getting his way, at any cost.

Turquoise knows the sensible choice would be to marry the wealthy senator and enjoy a lifetime of comfort and status. But her heart has chosen differently. If she dares to follow her passion--and defy one of Texas's most powerful and ruthless men--she and her defiant cowboy are in for the fight of their lives. . .

Praise for the novels of Georgina Gentry

"Delicious, entertaining. . .full of action, snappy dialogue, and humorous characters. . .readers will laugh out loud with this winner." --Romantic Times on To Wed a Texan (4 stars)

"The most delightful western of the season." --Romantic Times on To Tempt a Texan (4 1/2 stars, Top Pick, and KISS Award for the hero)

"Gentry has cleverly given the Beauty and the Beast tale a western twist." --Booklist on Diablo

Release date: January 1, 1851

Publisher: Zebra Books

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Rio:

Georgina Gentry

Padraic Kelly looked around at the cactus and barren land, then chafed at the hemp rope around his neck that also tied his hands behind him. The oxcart he stood in creaked under his feet as the animal stamped its hooves in impatience and the smell of blood and gunpowder.

In the gray light of dawn, the roar of cannons and the screams of dying men echoed across the desert battleground.

Ah, but by Saint Mary’s blood, the delay would not be long enough for the thirty condemned soldiers. Padraic turned his head and looked down the line of other men standing in oxcarts, ropes around their necks. Some of them seemed in shock, some had their eyes closed, praying to the saints for a miracle.

There’d be no miracles this morning, Padraic thought bitterly and wished he could reach his rosary, but it was tucked in the breast pocket of his uniform. It was ironic somehow that he had fled the starvation of Ireland to come to America and now his new country was going to execute him.

The colonel walked up and down the line of oxcarts, the early sun glinting off his brass buttons.

“Beggin’ your pardon, sir,” Padraic called, “for the love of mercy, could ye hand me my holy beads?”

The colonel sneered, his tiny mustache wiggling on his ruddy face. “Aw, you papist traitor! You’ll not need your silly beads when the flag falls. We’re sending all you Irish traitors to hell, where you belong.”

He should have known better than to ask the Protestant officer for help. Hadn’t he and most of the other officers treated all the new immigrants with disdain and bullying, which was the very reason some of the St. Patrick’s battalion had gone over to the Mexican side? It hadn’t seemed right, fighting fellow Catholics just because America had declared war on Mexico.

A curious crowd of peasants gathered, most with sympathetic faces, but the American soldiers held them back. There was nothing the unarmed peasants could do to rescue all these condemned men.

Padraic mouthed a silent prayer as he stared at the distant castle on the horizon. The early sun reflected off steel and gun barrels as the soldiers of both sides battled for control of the landmark. Smoke rose and men screamed and Padraic held his breath, watching the Mexican flag flying from the parapet.

“Yes, watch it!” The colonel glared up at him. “For when it falls and is replaced by the stars and stripes, you cowardly traitors will die!”

The Mexicans seemed determined to hold the castle as the hours passed and the sun moved across the sky with relentless heat, throwing shadows of the condemned men in long, distorted figures across the sand.

Padraic’s legs ached from hours of standing in the cart and his mouth was so dry, he could hardly mouth prayers anymore. Behind him he heard others in the oxcarts begging for water. Padraic was proud; he would not beg, though he was faint from the heat and the sweat that drenched his blue uniform. He knew they would not give the condemned water anyway. Their guards did bring water to the oxen and Padraic tried not to watch the beasts drinking it.

In one of the carts, a man fainted and the colonel yelled for a soldier to throw water on him. “I don’t want him to miss that flag coming down!” he yelled.

Padraic could only guess how many hours had passed from the way the sun slanted now in the west. The castle itself was cloaked in smoke and flames. He began to wish it would soon be over. Better to be dead than to stand here waiting all day in the hot sun for the hanging.

Sweat ran from his black hair and down the collar of his wool Mexican uniform. God, he would give his spot in Paradise for one sip of cool water. Well, his discomfort would soon be over. He didn’t regret that he had fled the U.S. Army; he had done it because of his love for a Mexican girl. That love had transcended everything else. He did regret so many had followed him, some of them so young and barely off the boat. They had been escaping from the potato famine, but now they would die anyway.

The heat made dizzying waves across the barren landscape and he staggered a little and regained his footing. If he must die, he would go out like a man.

The crowd of sympathetic peasants was growing as word must have spread that the Americans were hanging their deserters. Padraic looked around for Conchita, hoping, yet dreading to see her. He did not want his love to see him die this way.

Hail Mary, Mother of God … He murmured the prayer automatically and he was once again a small boy at his mother’s knee as they said their beads together. Now she would never know what happened to her son who had set off for the promise of America. It was just as well. He’d rather her think he was happy and successful than know he had been hanged like a common thief.

The riches of the new country had not been good, with so many Irish flooding in and everyone hating and sneering at the immigrants. If he could have found a job, he wouldn’t have joined the army, but no one wanted to hire the Irish.

The fighting in the distance seemed to be slowing, though he choked on the acrid smell of cannon smoke and watched the castle burning in the distance. The Mexican flag flew bravely on the parapet but he could see the bright blue of the American uniforms like tiny ants as the invaders attacked the castle. It wouldn’t be long now. The ropes bit into his wrists and he would give his soul for a sip of cold water, but he knew better than to ask. He closed his eyes and thought about the clear streams and the green pastures of County Kerry. He was a little boy again in ragged clothes, chasing the sheep toward the pens with no cares in the world save hoping for a brisk cup of tea and a big kettle of steaming potatoes as he ran toward the tumbledown stone cottage.

If only he could see Conchita once more. He smiled despite his misery and remembered the joy of the past three months. The pretty girl had been the one bright spot in his short, miserable life. He closed his eyes and imagined her in his arms again: her kisses, the warmth of her skin. He hoped she had not heard about the court-martial and the public hangings. He did not want her to see him die, swinging and choking at the end of a rope like a common criminal.

The rope rasped against his throat, the ox stamped its feet, and the cart creaked while Padraic struggled to maintain his balance. The colonel had stood them here all afternoon and now he almost wished the cart would pull ahead because he was so miserable, with his throat dry as the barren sand around him and his arms aching from being tied behind while his legs threatened to buckle under him. No, he reminded himself, you are going to die like a man, and a soldier. You just happen to be on the losing side.

In the distance, he could see the blue uniforms climbing ladders up the sides of the castle as the fighting grew more intense. Screams of dying men mixed with the thunder of cannons and the victorious shrieks as the Americans charged forward, overrunning the castle now as the sun became a bloody ball of fire to the west.

The ruddy colonel grinned and nodded up at Padraic. “It won’t be long now, you Mick trash. I knew I could never turn you Irish into soldiers.”

“If ye’d treated us better, we wouldn’t have gone over to the other side, maybe,” Padraic murmured.

The colonel sneered. “And look what you get! We’re hanging more than the thirty I’ve got here. General Scott asked President Polk to make an example of the Saint Patrick’s battalion. If it’d been up to me, I’d have hung the whole lot, especially that John Riley that led you.”

“Some of them would rather have been hung than to have been lashed and branded,” Padraic snarled.

“It’s better than being dead,” the colonel said. Then he turned and yelled at the soldiers holding back the Mexican peasants. “Keep those brown bastards back. We don’t want them close enough to interfere with the hanging.”

Padraic watched the peasants. Some of them were on their knees, saying their rosaries, others looking up at them gratefully with tears making trails down their dusty brown faces.

“Paddy, dearest!” He turned his head to see Conchita attempting to fight her way past the soldiers.

“Hold that bitch back!” the colonel bellowed. “Don’t let her through the lines.”

“Get your filthy hands off her!” Padraic yelled and struggled to break free, although he knew it was useless. Conchita was so slim and small and her black hair had come loose and blew about her lovely face as she looked toward him and called his name.

There was too much roar of battle now as the Yankees overran the castle for her to hear him, but he mouthed the words, I love you.You are the best thing that has happened to me since I crossed the Rio Grande.

She nodded that she understood and her face was so sad that he looked away, knowing that to see her cry would make him cry, too, and he intended to die like a man.

A victorious roar went up from the American troops as they finally fought their way to the top of the distant tower. It would only be a few moments now.

“Take her away,” Padraic begged his guards. “I don’t want her to see this!”

The colonel only laughed. “No, we want all these Mexicans to see what happens to traitors. Why don’t you beg, Kelly? Don’t you want your little greasy sweetheart to see you beg for your life?”

In the distance, the American soldiers were taking down the ragged Mexican flag, but even as it came down, one of the young Mexican cadets grabbed it from the victors’ hands and as they tried to retrieve it, he ran to the edge of the parapet and flung himself over the edge to the blood-soaked ground so far below. The Mexican peasants sent up a cheer, which the colonel could not silence with all his shouting. The cadet had died rather than surrender his country’s flag to the enemy.

Now the American flag was going up, silhouetted against the setting sun. The peasants shouted a protest as soldiers climbed up on the oxcarts and checked the nooses. “No! No! Do not hang them!”

Conchita screamed again and tried to break through the line of solders holding back the crowd. “Paddy! My dear one!” She couldn’t get to him, although she clawed and fought.

Padraic smiled at her and gave her an encouraging nod. If only things were different. He would have built a mud hut on this side of the Rio Grande and lived his life happily with this woman. If only he could hold her in his arms and kiss those lips once more.

Conchita looked up at him, her brave, tall man with his fair skin and wide shoulders. She made one more attempt to break through the guards, but they held her back. A roar of protests went up around her from the other peasants. He was her man and they were going to execute him and there was nothing she could do to stop it. She screamed his name and tried to tell him the secret, shouting that she carried his child, but in the noise of distant gunfire and the peasants yelling, she wasn’t sure he understood, although he smiled and nodded at her and mouthed I love you, too.

“Your child!” she shrieked again. “I carry your child!”

At that precise moment, she heard the officer bark an order and all the oxcarts creaked forward. For just a split second, the condemned men swayed, struggling to keep their balance, and then the carts pulled out from under the long line of soldiers and their feet danced on air as they swung at the end of their ropes.

Conchita watched in frozen horror and tried to get to her Paddy as he fought for air, but the soldiers held her back. Her eyes filled with tears and the sight of the men hanging grew dim as they ceased to struggle.

“This is what the U.S. Army does to traitors and deserters!” the colonel announced to the crowd with satisfaction.

Conchita burst into sobs. She was in great pain as if her heart had just been torn from her breast. She did not want to live without her love, but she must, for his child’s sake. She was not even sure he had heard her as she tried to tell him he would be a father. If it were a boy, she would raise that son and call him Rio Kelly for his father and the river that made a boundary between the two civilizations. And then she would go into a cloistered order and spend her life praying for the souls of her love and the other condemned men.

The soldiers were cutting the thirty bodies down now, and she broke through the line of guards and ran to her Paddy as he lay like a tattered bundle of rags on the sand. She threw herself on the body, weeping and kissing his face, but his soul had fled to his God and he could no longer feel her kisses and caresses.

Only now did she realize he had died smiling and so she knew he had heard her and knew he would have a child.

On the outskirts of Austin, Texas, mid-April 1876

Turquoise Sanchez knew she was introuble when her mare began to limp. She dismounted and patted Silver Slippers’s velvet muzzle. “Now what are we to do?” she murmured to the dapple-gray horse as she examined the loose shoe.

Silver Slippers nuzzled her owner and blew softly.

Turquoise looked around, assessing the situation. She was several miles from her downtown hotel and at least two miles from her friend Fern’s ranch. In her tiny riding boots, with the midmorning sun getting hotter, walking and leading the mare didn’t seem very appealing.

She sighed and took off her large-brimmed hat that shielded her face from the unforgiving sun and felt perspiration begin to break out under her turquoise, long-sleeved riding outfit. The turquoise and silver jewelry she wore now felt heavy on her small frame, and her long black hair was partially loose from its pins. She must look a mess.

Well, she’d gotten herself into this predicament. Most young women her age would never have gone riding alone, but then, Turquoise was more daring and resourceful than most young ladies.

“Silver Slippers, we’ll just have to walk up this road a ways and see if we can find some help.”

That wasn’t likely to be forthcoming, she thought as she began to walk; this was a deserted dirt road without much traffic. At least Uncle Trace would become alarmed when she didn’t meet him for luncheon at the hotel and would come looking for her. Except she hadn’t left any messages as to where she was going. Sometimes it was not wise to be so independent.

Stubbornly, she set off walking up the road, leading the limping mare. Surely along this road somewhere she would run across a ranch or some chivalrous gentleman who would come to her aid. “Dammit,” she muttered as she trudged forward, kicking at stones with her small riding boots. “What do I do now?”

She walked another quarter of a mile, perspiring and annoyed. She needed a cold drink of water and so did her mare. Turquoise rounded a curve in the road, and ahead she saw a small, rather run-down building with a rusty sign that read BLACKSMITH.

Sometimes the good saints do answer prayers, she thought. Without thinking, she crossed herself and walked faster. As she grew closer, she noticed a movement inside the big door and saw a man, and what a man.

He was tall, muscular, and very tan with a mop of unkempt black hair. He was naked to the waist and a silver cross gleamed on his sweating chest as he hammered on a piece of metal.

“Hello! Are you the blacksmith?” she called and he looked up, staring at her with big dark eyes. Mexican, she thought, or at least part Mexican.

“Si, senorita,” he nodded as she approached. “How may I be of service?” He had a Mexican accent, as she expected, and a pleasing deep voice.

Rio Kelly watched the girl approaching him. She was a small woman, smartly dressed, and everything about her spoke of wealth. She led a very fine dapple-gray horse, also of quality, just like the young lady.

She frowned as she walked up. “Some water for me and my horse,” she snapped.

This was evidently a spoiled, high-class girl who was used to being waited on.

“You might at least say ‘please.’” He pulled a handkerchief out of his back pocket and wiped the sweat from his dark face. Despite her ebony hair, she had light-colored eyes and very creamy white skin.

“I’m sorry,” she apologized. “I’m hot and thirsty and, as you can see, in need of some help.”

He stepped forward and took the reins from her hand and felt almost an electric shock as their two hands touched, although his was so much larger and stronger than hers. “There’s a horse trough by my building and I’ve a well nearby. Let me get you a drink.”

“Gracias—I mean, thanks,” she blurted and he wondered again about this turquoise-eyed beauty. Her eyes were large and the color of a pale sky. “My mare has a loose shoe and I need to get back to town.”

“Such a fine mare. She must have cost a fortune.” He took in the wealth of silver and turquoise jewelry she wore and the fine leather boots.

The girl shrugged. “My guardian bought her for me two days ago.”

“Does he buy you everything you want?” He was abruptly annoyed with the wealthy girl.

She blinked as if wondering why he was so short-tempered. “Not everything, but I wanted this mare.”

He looked at her critically. “It’s very warm to be wearing long sleeves and such a big hat.”

“To protect myself against the sun,” she said. “Ladies always protect themselves against the sun. It darkens the skin.”

She had the lily-white skin of the rich gringos. He led the dapple gray over to the trough, where the horse drank gratefully. Rio tied the mare up and gestured toward the well. “Here, senorita—I mean, miss—let me get you a drink.”

“‘Senorita’is all right.” She nodded. “I, too, am Mexican.”

She didn’t look Mexican, but he didn’t say that. Instead, he led her around the building and down the lane a few yards to the well where he brought up a bucket of cold spring water, reached for the metal dipper, and offered it to her.

Even as she drank, he noted she was staring at his hand.

“A four-leaf clover?”

He glanced down at the small tattoo on the back of his right hand. “For my father. He was Irish. Allow me to introduce myself, senorita. I am Rio Kelly.”

“Odd combination,” she murmured and sipped the water again.

“I’m half-Irish, half-Mexican,” he said by way of explanation and smiled at her in spite of himself.

“I am Turquoise Sanchez,” she said, “and I need to get back to town to meet my uncle for lunch.”

He nodded. “Si. As soon as I can heat my forge a little more, I’ll get a new shoe on your horse.”

“Gracias,” she said and took off her big hat, fanning herself with it.

She had the most luxurious long black hair and it was falling out of its pins and down on her shoulders. With her unusual turquoise eyes, he thought she was the most striking woman he had ever seen.

“Come then,” he gestured and turned back to his shop. As they walked, she fanned herself with her big hat and looked around. “Lovely landscape. Do you own all this?”

He chuckled as he strode into the shed and she followed.

“Hardly, only fifty acres, this shop and that barn and house up there on the hill.”

She turned and looked at a modest adobe ranch house and a red barn. “It’s still very nice.”

He shrugged and grabbed the bellows, blowing the fire still bigger. “There’s five thousand acres next to me, but it’s owned by some big New York company and I can never hope to earn enough to buy it.”

She watched him as he grabbed his pliers and strode out to her mare, lifted the dainty hoof, and talked softly to Silver Slippers. “Ah, beautiful one, you’ll let me change your shoe, no? Then you won’t limp.”

“Careful, she can be a little wild,” Turquoise cautioned. “She has not been treated well.”

He looked the mare over and scowled at Turquoise. “This mare has whip marks on her.”

“I didn’t put them there,” she said, defending herself. “My guardian and I were out for a walk two days ago and I saw a well-dressed young drunk beating this horse. Before I thought, I ran out, took the whip from him, and struck him several times. Then my guardian knocked the man down and insisted he sell us the horse.”

“Ah,” the blacksmith said, nodding approval.

“So now she’s my baby and I love her.”Turquoise stroked the mare’s velvet muzzle and the mare whickered and nuzzled back.

“I’d say the feeling is mutual,” the man said and smiled, showing even white teeth in his dark face. He looked at Turquoise over his muscular shoulder, then returned to taking off the loose shoe as he reassured the mare. “Horses like me.”

Silver Slippers barely blinked as he examined her hoof.

“Well,” Turquoise said, surprised, “you really do have a way with horses.”

He came back to the forge, picked up a new shoe, and held it in the fire. As it began to glow, he pounded and hammered it into shape. “And what are you doing in Austin, Senorita Sanchez?”

“I’m here for the big debutante ball tonight at the governor’s mansion,” she said. “Are you going?” Then she felt foolish as he paused in pounding the horseshoe and stared at her, a slight smile on his handsome face.

“Do I look like I fit in with Austin’s fancy gringos?” he asked.

“I’m sorry,” she murmured.

“Don’t be.” He shrugged his wide shoulders and examined the glowing horseshoe a long moment. “The Mexican population hardly knows what the gringos are doing and care less.”

“Well, it’s at the governor’s home,” she said. “Surely you have seen the governor’s home?”

“Only from a distance,” he said and, picking up the glowing shoe with his pliers, he carried it out to the horse trough and dunked it in, where it hissed and sent up steam as it cooled. “I’m sure, though, you will be the most beautiful lady there.”

She felt herself flush at the bold way his dark eyes looked her over. “I doubt that. I’m sure there will be many of the most beautiful girls from the very best families.”

He chuckled and she winced at the past memory. From the very best families. It had only been half a dozen years that her guardian had sent her away to the fine Houston school for upper-class Texas girls, most from Stephen Austin’s original Three Hundred, the blue bloods of Texas founders. The girls had been so cruel to her that she had stayed only a week before fleeing back to the Durangos’ ranch. She never told her guardian why she didn’t like the private school. She was too proud to say that the gringa girls had taunted her about her Mexican name, teasing her with cruel words like “hot tamale” and “greasy Mexican girl.”

“There, senorita.” He held up the horseshoe, bringing her out of her memories with a start as he walked with the horseshoe back out to her mare.

Turquoise watched him pick up the mare’s hoof and gently and expertly pound the shoe on while the horse seemed unconcerned. “You are better than good with horses,” she said.

“Gracias.” He smiled at her. “Someday, I hope to make a living strictly as a vaquero and raise fine cattle and horses, but right now that’s not possible.”

“Well, I will pay you handsomely.” She stepped forward, opening her small reticule.

“I did not mean to hint for more money.” His expression turned cool.

“Oh, I intend to tip you for your trouble. After all, if you hadn’t helped me—”

He backed away from her, holding out one big, calloused hand. “The charge is one dollar, miss, and I am not a lowly servant to be tipped by a rich lady.”

“I only meant …,” she stammered as she realized she had humiliated him. “All right, one dollar.” She put the silver in his palm and waited for him to assist her in mounting her mare.

“I’m sorry.” He ducked his head. “You see how dirty my hands are and I wouldn’t want to spoil your fine dress.”

“Yes, of course.” She realized then she had been looking forward to feeling the strength of this big man as he lifted her to her saddle. “I’ve been raised on a ranch and am perfectly capable of mounting myself.” She swung up into her saddle and adjusted her hat so that it would protect her face from the sun. “Well, adios.”

He only nodded and she rode out at a brisk canter without looking back.

Rio Kelly stood holding the silver dollar and staring after the mysterious girl who was so obviously more white than Mexican, but had a Mexican name. This fine lady was far above him socially and not for the likes of a poor vaquero, but still, he knew he would think of her all the rest of the day.

Turquoise rode at a canter back to Austin and down Congress Avenue until she reined in in front of the Cattlemen’s Hotel, the finest of its kind in all Texas.

The doorman hurried out to meet her and took the reins as she stepped down.

“What time is it?” she asked.

He pulled out a pocket watch. “Nearly noon, ma’am.”

Turquoise heaved a sigh of relief as she turned to him.

“Please put my horse in your stable and give her a good rubdown and plenty of water. She’s had a long ride.”

“Yes, miss.” He nodded with a smile, and she tossed him a coin.

That made her think of the haughty but poor blacksmith who had spurned her tip. Oh, well. She hurried inside and up the stairs to her suite of rooms.

Good, Uncle Trace wasn’t here, which meant he was probably in the bar or in the lobby reading the papers.

She took off her hat and laid it on the dresser, looking in the mirror. She felt a fine layer of dust on her pale face and took off the long-sleeved riding outfit, then sighed as the cooler air touched her skin.

Walking to the bowl and pitcher, she poured a bowlful and proceeded to wash herself, especially her face. Then she sprayed herself with forget-me-not cologne.

Turquoise brushed her hair and put it up on her head with silver clips. Then she selected an expensive, pale pink lawn dress and tiny white slippers.

Now she picked up a lace, beribboned parasol that matched the dress and went down the stairs to lunch.

The maître d’ met her at the dining room door and bowed. “Your uncle is already seated, miss.”

“Gracias,” she said and followed him across the crowded dining room, ignoring the many men whose gazes seemed to follow her path.

“Dios,Turquoise, where have you been?” Trace Durango got up from his chair to greet her as the maître d’pulled out hers. “I was worried about you ridin’ that new horse.”

“It’s a long story,” she said, reaching for a linen napkin. “Silver Slippers is a wonderful mare, but she had a loose shoe and I was sort of stranded until I found a blacksmith.”

His dark face frowned. “I’ve told you not to go ridin’ alone. A girl could get into trouble in this big town, or get thrown by a spirited horse.”

“Oh, stop fussing over me.” She picked up her menu, noting that her half-Cheyenne, half-Spanish guardian was still handsome, although his black hair was graying at the temples as he approached forty. “I ride well. You should know. You taught me. By the way, we are going to shop for a ball gown after lunch, aren’t we?”

He sighed heavily. “Now that’s one chore I could do without. Reckon I could just sit in the buggy while you do it?”

“You are planning on coming tonight, aren’t you?” she asked, looking over the menu.

“Si, but I’d rather be horsewhipped than get all dandied up and mix with these gringo city snobs. Honestly, Turquoise, I don’t know why this means so much to you.”

“Because all Texas girls of good family have to be presented as debutantes, or so the Austin papers say.”

“Huh,” he reminded her, “we sent you to mix with those snooty girls once at t. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...