- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

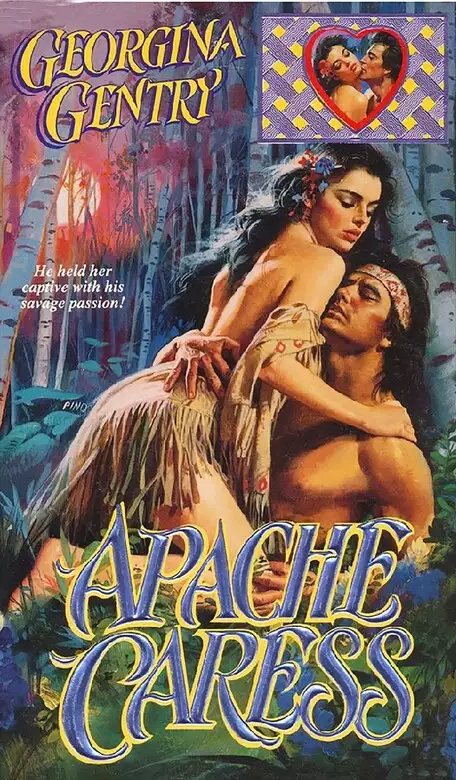

SHE WAS HIS CAPTIVE Cholla seethed with fury. The Apache scout had risked his life tracking down renegades for the white man only to find himself chained like an animal on the army prison train. Well, if they wanted a vicious savage, he'd give them one—he'd even force a white woman to help him escape. Sierra Forester had gotten in his way, and he was in no mood to let the beautiful widow go. He didn't intend to harm her, but it was a long way from St. Louis to Arizona, and along the trial he vowed to discover exactly what his lovely captive knew about satisfying a man's desires. . . and unleashing her own! HE WAS HER PASSION Every day Sierra grew less afraid of her savage captor. At first she thought he would kill her. . . or worse. After all, her husband had died at the hands of the Apache. But this Indian seemed to have more honor and courage than anyone she'd ever known. As they moved west, the handsome warrior protected her bravely from wild animals and wilder men—and tempted her with delights she'd never imagined. Now her traitorous soul hoped she'd never be free from his muscular embrace and searing touch. Her urges were scandalous, but Sierra could resist no longer. She would give anything to savor the wild ecstasy of his. . . APACHE CARESS.

Release date: May 16, 2014

Publisher: Splendor

Print pages: 296

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Apache Caress

Georgina Gentry

Sierra thought about it again as she carried a box of dishes out the door and lifted it into the wagon. At least there wasn’t much to pack and load. She squinted at the late afternoon sun. By tomorrow morning, she who had never been allowed to make decisions, had to decide what to do with the rest of her life.

With a sigh, she brushed a wisp of black hair back into its bun and leaned against the wagon, listening to the lonely whistle of an approaching train. It sounded as forlorn as she felt. She looked toward the track running just past her fence a hundred yards away. How she envied the passengers as she watched the engine puff toward her from the west. At least some people in this world were safe and secure and knew where they were going.

Sierra wished she could say the same. Reared by a stern, protective grandfather, then married last spring to a dominating cavalry officer, Sierra had resisted her rebellious impulses and done as she was told. Now, with both of them dead, she felt like a small bird thrown out of its cage into a hostile world it was unprepared to deal with.

The train chugged toward her, black smoke drifting on the warm September air. Sierra wondered where it had come from and where it was going? Only a few miles behind that train lay the wide Mississippi. She had never even been west of that river, much less far away to the mountains she was named for.

A cinder blew from the smokestack onto the sleeve of her plain black dress, and she brushed it away. The train was abreast of her now, and Sierra stared at the vague outlines of people in the coach windows, wondering who they were and where they had come from. Her wild, reckless young mother had longed to go West and had never fulfilled that dream.

The train whistled again. Two men came out of one of the passenger cars, moving across the connection toward the baggage car behind. They paused on the swaying platform. The second man wore a blue uniform, but Sierra hardly saw him, her attention being centered on the big, wide-shouldered one. Merciful heavens, an Indian. A red-skinned savage. Sierra recoiled at the thought, staring at the dark-skinned man. Naked to the waist, the silver conchos of his tall moccasins reflecting the late afternoon sun, he stared back at her with moody eyes as dark as her own. He wore buckskin pants and a red headband that held straight black hair back from his ruggedly handsome face.

The way he looked at her compelled Sierra to touch the throat of her prim widow’s dress to make sure it was buttoned. Wild and male as some range stallion, Sierra thought, and noted with relief that he wore shackles.

Indians. It was because of them that Robert lay dead in a hero’s grave far away in Arizona and she was alone in the world. She glared at the savage, hoping that the Army was taking him somewhere to be hanged.

Cholla paused on the swaying platform, watching the white girl standing by the small, canvas-covered wagon. Why was she glaring at him as if she hated him? It made no sense, but then who could understand the thinking of whites? Cholla had scouted for the Army against renegades like Geronimo, yet the Apache scouts were now being shipped to that same Florida prison as the hostiles.

Anger at the injustice and the betrayal smoldered in his soul, fueled by the way the dark-haired girl put her hand to her throat as if she feared even his gaze.

Lieutenant Gillen pushed him roughly. “Blast it all! Get on in that baggage car!”

Cholla half turned, ready to strike out at his captor, then realized this wasn’t a good time or place to attempt to escape. And he intended to escape . . . or die trying.

He let Gillen shove him into the baggage car, thinking he had not lain with a woman in many weeks.

But it was not an Apache woman or even a Mexican cantina girl he thought of now. In his mind, he imagined that white woman shaking her long hair loose from its pins so it blew wild and free about her naked, pale shoulders as she slowly peeled off the black dress. Her face had been brown as any Apache’s from the sun, but under the black fabric, her breasts and thighs and belly were surely as pale as the mountain snows of the high country.

Gillen slammed him up against a stack of crates in the swaying baggage car. “You damned Injun! I saw the way you looked at the white girl! Got rape on your mind, do ya?” He tried to kick Cholla between the thighs, but the Apache managed to protect himself.

“You’re voicing your own thoughts.” Cholla glared at him. “If you weren’t armed, and I weren’t chained hand and foot, you wouldn’t be so brave.”

The officer laughed and hefted the rifle in his hands. “You’re smart, Cholla, too damned smart! You know I’m looking for any excuse to kill you before I finally have to unload this train at Fort Marion.”

“Just remember”–Cholla smiled without mirth–“if you kill me, you’ll never find out what you want to know.”

Gillen pushed his hat back on his brown, curly hair and swore softly. “You red bastard, there’s two things I aim to find out!”

Cholla looked at the shorter man. “You’re running out of time, Lieutenant.”

Gillen took a paper bag full of candy from his jacket, popped a piece in his mouth. Even from where he was, Cholla could smell peppermint on the lieutenant’s breath. “Blast it all, why do you think I brought you back here away from the other prisoners? I intend to beat it outa you!”

Cholla wished he could get his hands on that rifle. “All I’ve got to do is yell, and the other soldiers will come running.”

“After serving with you, Cholla, I figure I know you pretty damned well. You’re too proud to scream for help.” Gillen leaned against the small window. “Tell me what really happened that day to Forester, and tell me about the gold.”

Cholla shrugged, watching for an opening. “It was all in Sergeant Mooney’s report; you read it. As for the gold, you know the Apache god, Usen, forbids us to dig for it.”

“But you all know where’s it’s likely to be found,” the lieutenant insisted.

Cholla’s skin felt raw from the iron fetters. He rubbed at his wrists, and the chains rattled. “If you say so. I’m just a scout.”

“Blast it all! Don’t be so damned calm and superior with me, you damned Injun!” Gillen rolled the candy around in his mouth, hefted the rifle.

“Why hurt the innocent with the truth?”

“God damn it! The truth is what I want to know!” Lieutenant Gillen advanced on him.

“The men who survived that ambush know; no one else ever will.” Cholla forced himself to control his temper. He must not attack the officer. That was what Gillen was after, an excuse to beat him senseless or kill him.

“You blasted red bastard! I’m gonna kick you bloody! You’ll tell me everything before I finish with you!” He brought his rifle back, slammed the butt hard against Cholla’s ribs.

The pain was worse than the Apache had expected. He went for Gillen’s throat, mindless, enraged. As he attacked, the officer swung the rifle again, catching Cholla across the ribs, knocking him back against a stack of boxes in the swaying, noisy car. The boxes fell with a crash, but Cholla managed to keep his footing, even though the breath had been knocked out of him. All he could do was double over, gasping for air, stalling for time as the officer advanced on him.

Gillen smiled slowly. “You attacked me, scout. That’s all the excuse I need. When I get through slamming you between the legs with this rifle butt, you’ll never top another woman, much less look at a white one!”

His flesh seemed afire with bruises, but Cholla feigned even more pain than he felt. Under his feet, the train swayed into a curve, beginning to slow its speed. If he could get that rifle, he would kill Gillen. After that, he didn’t care what the Army did to him. Even hanging was better than life in a cage thousands of miles from home. He didn’t straighten up. “Please,” he gasped. “I’m hurt . . . don’t hit me again. I . . . I’ll tell you what you want to know.”

The officer hesitated. “Didn’t think it would be this easy, you lousy redskin. Maybe you’re not as tough as you–”

Cholla dived for his legs. Even though the train seemed to slow as it went into a wide curve, the momentum and the swaying caused them both to hit the floor hard. They rolled over and over in dust and a tangle of chains, the clatter and the puffing drowning out the desperate sounds of their life-and-death fight.

The chains hampered Cholla. Gillen managed to stumble to his feet, a triumphant gleam in his eye as he cocked the rifle. Recklessly, Cholla charged him again. Gillen would kill him anyway, he might as well take the white man with him.

They meshed and fell against a stack of heavy crates that swayed dangerously. Now Cholla slammed Gillen up against the small window, and it shattered as they fought for the gun. If he could just cut the white man to pieces against the jagged glass . . .

But Gillen seemed to sense Cholla’s thought as he, too, twisted to throw the Apache scout’s arm against the knifelike shards. Cholla’s warm red blood smeared them both as the train slowed to a crawl in its curve.

By Usen, he had to get that rifle. Oblivious to pain, Cholla fought with desperation, slammed Gillen hard against the wall. With an agonized cry, the white fell, and the rifle flew out of his hands just as the crates crashed down.

Fettered as he was, Cholla just barely jumped out of the way. Gasping for breath, he managed to keep his balance, his body one aching mass. Gillen lay covered with blood, motionless near the crates. Dead, Cholla thought with relief, and he turned his attention to the rifle wedged under the fallen boxes. He needed that weapon. At any minute, another soldier might come back to investigate why they had been gone so long.

Cholla looked out the shattered window. Late afternoon, thousands of miles from home. If he had the rifle, he might have a chance. The train gradually slowed to a crawl.

With superhuman effort, he put his wide shoulder against the crates, trying to move them. He felt the veins in his massive body bulge. Sweat stood out on his bloody, naked skin as he threw his strength into the effort. Whatever was in the crates, it would take more than one man, no matter how strong, to move them. And the rifle was under them.

Beneath his feet, Cholla felt the swaying train begin to pick up speed as it came out of the curve. He knew he had to make a choice. Soon it would be hurtling down straight track and jumping would mean certain death. Yet how could he survive in this white man’s country without a weapon?

He struggled again to move the crates, groaning with the effort. The train whistled as it picked up speed, clacking over the tracks. In another minute, it would be moving too fast to jump, but staying meant he’d be hanged when the soldiers found Gillen’s body.

Cholla didn’t have much choice. However slim his chances were in this strange country far from home, he would have to try to escape. He had lived most of his thirty years on the edge, always taking risks. To do otherwise was not living but existing like a bird in a cage; the same kind of cage that had awaited him in Florida. Captive security against dangerous freedom. Better to take his chances jumping.

The chains clanged as he stumbled out onto the swaying platform between the cars. Cinders blew past him in a cloud of smelly smoke. By leaning out, he could see a downhill slope ahead. The train would be picking up speed, hurtling down the hill in only seconds more. To leap then was to die. Remaining, he’d be hanged when the soldiers found the body.

Cholla took a deep breath, said a prayer to Usen and jumped as far as he could, hoping to clear the hurtling cars. For what seemed eternity, he hung in midair. If his chains caught on anything, he would be dragged under the giant wheels and killed. Or worse yet, maimed.

He hit the ground hard and rolled. Cholla remembered the smell of crushed weeds, the numbness of his flesh, the taste of blood from his cut lip. He told himself to get up. They would be looking for him. But he could not force his muscles to respond.

Dimly, he heard the distant whistle, the far-off chugging of the train. He lay there, listening to the fading sound, expecting to hear the shrieking squeal of brakes as someone found the dead man, pulled the emergency cord. Cholla struggled to sit up in the patch of tall weeds. Through them, he saw the train still moving away, swaying and puffing as its speed increased.

He must leave this place. Very soon someone would find Gillen and the train would back up, the soldiers looking for him along the tracks. He needed to get far away before that happened. Uncertainly, he got to his feet and assessed his injuries; weary, dirty, and bloody from the glass cuts–but no broken bones.

Cholla glanced toward the late afternoon sun. Under cover of darkness, he had a better chance. Chance of what? The chains rattled as he moved. No weapon, no food, no one to help him. At least fifteen hundred miles from familiar territory. In the distance, the train disappeared over the rise, but its whistle echoed and its smoke hung on the pale blue horizon. He began to work his way through the tall weeds.

When he found a small creek, he walked down it to confuse the tracker dogs the Army might bring in. Then afraid of being seen, he drank his fill and lay in the shelter of some bushes, waiting for darkness to fall.

What was he going to do? Up until now, he had thought only of surviving minute to minute, but he was a seasoned warrior, used to danger and hardship. Coolly, he began to think and make plans.

If only his friend, Tom Mooney, were here. Sikis– brother, he thought. But Tom had been left behind at the Arizona station, arguing with his superiors and risking court-martial by trying to prevent Cholla and the other loyal Apache scouts from being forced on that train. Cholla didn’t even want to think about what had happened to his horse and his dog. They were no doubt dead, as was beautiful young Delzhinne, and as he himself soon would be.

One thing was certain, he would not go to his grave without a fight. Deep in his heart, he knew he had no chance of making it all the way back to the West. Only a few miles from here lay that big river, the Mississippi, and it was too wide to swim. By Usen, he could not win, but he would not quit. When they killed him, he would go down fighting. That was what made the whites hate him so; he wouldn’t conform. He wouldn’t bend, and they couldn’t break him. Cholla, like the desert cactus he was named for, was tough, dangerous to tangle with.

He rested until dark and then began to travel. Tired and hungry as his brawny body was, his mind was clear. Many times he had been in bad situations, but his level head and bravery had saved him. Not only the Army but armed citizens would be searching for him, eager to kill. If he were to have any chance at all, he had to get the chains off. But to do that, he needed tools; blacksmith’s tools or maybe an axe. Where were such tools found?

Farms. Cholla looked down at the chains on his wrists and ankles. He must find a farm where there were no dogs to scent him and give the alarm. Most whites owned dogs. When the creatures barked, men came out with guns.

He tried to maintain a slow trot, the chains jangling as he moved. Lithe as a puma, though a big man, Cholla concentrated on putting distance between him and where he had jumped from the train. And then what? he thought ruefully. If he managed to travel all those miles back to the big river, how would he get across? He could hardly walk across that giant bridge. Maybe he could sneak aboard a freight train headed west across it.

With that thought, he paused when he saw the rails gleaming in the moonlight. Yes, maybe he could follow the tracks back, almost to the giant river, and sneak aboard a train. It might take the white men several days to get tracker dogs. Right now, his first priority was getting the chains off.

He walked along the tracks, headed west. Several times he stopped and scouted out a farm, hoping to find tools and food. But always the distant barking of dogs or the sight of men in farmhouse windows, made him decide to move on, seek an easier target. One thing was certain, he needed to be unfettered and on his way before daylight.

His belly growled, and his body ached. Dried blood stained his headband. But Cholla was used to hardship. His father had been killed by drunken warriors in a raid, and he, Delzhinne, and Mother had nearly starved before Mother began to clean and cook at the white soldiers’ fort. Cholla had grown up among whites. The last several years, he had scouted for the Army because he knew that leaders like Geronimo would only prolong his peoples’ ordeal. General Crook had given his word that they could stay in their beloved country.

However, General Miles had taken over and the promises Gray Fox Crook had made were no good. All the Apaches had been betrayed and gathered up to be shipped away to prison, even those who had served as Army scouts. Anger at the injustice burned deep in Cholla’s heart as he moved across the dark countryside. Never again would he trust the whites. He who had been lied to, mistreated, and shown no mercy would respond in kind.

Around him, crickets chirped in the dark night and somewhere a dog howled. The lonely sound echoed through the stillness, making him think of his own dog, Ke’jaa. Cholla winced when he remembered the chaotic scene at the railroad station as the Apaches were forced on board the train. Hundreds of the Indians’ dogs had run about in the confusion, barking and whimpering, trying to follow their masters onto the train. They had been beaten back by the soldiers.

Cholla had put his face against the window as the train pulled away. His friend, Sergeant Mooney, stood forlornly on the platform, the dogs barking and milling about, running after the departing cars. Ke’jaa. The name meant “dog” in his language. Big and half-coyote, his pet had run alongside the train for miles, trying vainly to keep up with Cholla while Lieutenant Gillen had laughed about the fate of the Apaches’ dogs once the train was gone. No doubt Ke’jaa had been shot along with hundreds of other dogs.

At least Gillen wouldn’t be riding Cholla’s fine stallion now. The Apache took some satisfaction in that thought as he paused and caught his breath. In the moonlight, he tried to get his bearings. Where was he and how far had he come?

Up ahead lay a farm. He could see faint light streaming through the windows of the small house near the train tracks. Were there dogs? If not, maybe he could steal some tools from the barn, or even a horse. If he were lucky, there might be a smokehouse with some ham or bacon. Though Apaches weren’t fond of pork, Cholla had lived too long with the whites to like mule meat and some of the other delicacies the wild Apaches relished.

Cautiously, Cholla slipped closer to the house. Out front was a small, canvas-covered wagon, the type a peddler might use. There was something familiar about this place, but he had passed a hundred such scrabble-poor farms on the long train trip.

He moved along, silent as a shadow, listening for a dog or maybe a man’s voice drifting through the open windows. Nothing. Out behind the house, a small barn stood silhouetted against the moon. He remembered then why the place looked familiar to him.

In his mind, he stood on the swaying train platform again, returning the stare of an ebony-haired girl in a black dress. She had glared at him, curious and yet hostile. Cholla remembered the hatred in her tanned face and wondered about it. It had been a long time since he had lain with a woman. But Apaches had a taboo against rape. They were afraid that evil spirits would haunt them for taking an unwilling woman. Still, the thought of the girl drew him slowly toward the small house.

I need to see if there are men on this place who might come out to the barn if they hear a noise, he told himself. Then he remembered that the woman had worn a black dress, the sign of a widow. Still there might be brothers or a father or some other male relatives who would shoot at him. He had better investigate the scene before he tried to take tools or food.

Cholla went to the window and looked in. The woman stood within, clad in a flimsy white garment, a photo in her hand. As he watched, she bent over a trunk, put the small framed photo inside, took out a hairbrush, and straightened. On the table were an oil lamp and one lone plate and cup. The scent of frying bacon and hot bread drifted from the stone fireplace through the open windows.

His heart pounded harder. The woman was alone. The one plate told him that. Alone and defenseless. His gaze swept the room looking for weapons. He saw none. Besides the trunk, there were boxes stacked about as if she were packing to leave.

His attention returned to the woman. The chemise was so sheer, Cholla saw the dark circles of her nipples through the fabric. Her skin was tan except where dresses protected it, and her pale breasts swelled beneath the white underthing. While he watched, she took the pins from her ebony hair, shook the locks out, and began to brush them.

Cholla watched the light reflect on her hair as she brushed, her breasts moving with each stroke. He had a sudden vision of her lying on the small rug before the fire, the thin chemise pulled up around her hips, her long black hair spread under her. Her mouth looked as soft and full as her breasts. He saw himself walking toward her as she smiled and reached up to him, spreading her thighs. He would lie down on her, covering her small, pale body with his big dark one. He would tangle one hand in her hair and lift her face up to his while his other hand pushed down the chemise. As he had thought, her breasts and belly were milky white where the sun had not touched her skin.

Cholla took a breath and then sighed, feeling his manhood hard and aching, wanting the relief the girl’s body could offer. She turned suddenly and stared toward the window as if she had heard the sound. He held his breath and did not move. Then she shrugged, as if convincing herself that it was only her imagination, and resumed brushing her hair. With each stroke her breasts moved, and Cholla imagined how they would feel when he closed his big, callused hands over them, the nipples erect against his palms.

He looked down at the fetters on his wrists and ankles. His very life and freedom were at stake; he had no time to think of women. His arm was bleeding again, but he couldn’t do anything about that right now. He moved as carefully as he could to keep from rattling the chains.

Turning, he crept toward the barn. Maybe he would find some blacksmith’s tools or at least an axe there. There must also be a horse, or the wagon wouldn’t be out front. It looked as if she was loading it to leave on the morrow. When he had first seen her from the train, the pure hatred in her stare had mystified him. She’d be even angrier tomorrow when she found a horse and some meat from the smokehouse missing. He could travel many miles before the widow found that someone had been about in the night.

Cholla paused at the open barn door, breathing in the scent of sweet hay and leather harness. An animal snorted and stamped its hooves in a shadowy stall as he crept toward it. He put his hand on the top rail, guiding himself through the darkness. As a scout, Cholla had had a lot of experience with cavalry mounts.

The animal snorted again. “Easy, boy,” he soothed. “Be still. Once I get these chains off, we’re leaving.”

Then Cholla brushed against something on the top rail, something fluffy and feathered that set up a terrible, loud squawking and wing-flapping.

A chicken. He had awakened a stray barnyard hen perched on the rail, and she’d set up a racket as if a fox were after her. As Cholla paused, uncertain what to do, the chicken squawked and flapped, further exciting the creature that was snorting, maybe at scenting the fresh blood on Cholla. The animal now began an ungodly heehawing.

By Usen, a mule. A damned mule. That creature and the noisy hen were making enough racket to be heard for miles.

What to do now? Cholla looked toward the house. Would the woman come out to investigate the racket? Maybe she hadn’t heard it.

She came to the window, peered out uncertainly. Cholla watched her, hoping she would stay inside. Even though she had looked at him earlier with eyes full of hatred, he didn’t want to kill her. He glanced at the chains on his wrists. By looping them over her head, he could break her neck before she had any chance to cry out.

In the darkness Cholla pressed his back up against the wall and held his breath. He heard a sound and twisted his head to look. The woman stood in the doorway of the small house. She held a rifle and a lamp. For a long moment, she hesitated as if afraid, then started toward the barn.

Cursing silently, Cholla pressed himself against the inside wall, listening to her footsteps coming closer. He had never hurt a woman, but there was no way out of it now. To insure his own safety, he would have to kill the one with the hate-filled eyes.

Sierra stood by the trunk in her chemise, holding the small photo and staring at Robert’s handsome face. It had been a whirlwind courtship and such a brief marriage before the dashing lieutenant was sent to Arizona Territory. Robert. He wasn’t the type to be called Bob. Under the shock of blondish hair, his almost turquoise-colored eyes stared back at her as cold and remote as his personality.

They had both had their pictures made that day. She wondered idly what he had done with hers? It hadn’t been among the little package of personal items included with the medals and the letter of condolence from his commanding officer.

Was there a chance he might have been carrying it with him so it had been buried with his body? She could only hope he cared that much, but in reality she knew better.

She was a widow because of a bunch of bloodthirsty Apaches. It was ironic somehow. At her stern grandfather’s urging, she had married Robert, though with misgivings. Now both men were dead, and she faced the world alone.

With a tired sigh, Sierra bent over the small trunk and tucked the photo in the tray next to Robert’s medals and her hairbrush. At least Robert hadn’t shirked his duty. Somehow Sierra had figured him for a coward. She felt guilty about that. She had hoped she and Robert could be reconciled, but now that would never be.

Sierra took the hairbrush out of the tray and pulled hairpins out, shaking her long ebony hair down to brush it. So few things to take, really: personal items, clothes, scissors and sewing notions tucked deep in the trunk, a few household items. The furnishings would stay with the house when banker Toombs and the sheriff came to put her out tomorrow. She intended to be gone before they got here. She brushed her hair with angry strokes.

Abruptly, Sierra had the eeriest feeling that she was being watched. She paused, looked around, realizing that she stood in a skimpy chemise near an open window.

Then she chided herself for being a fool and reminded herself that Grandfather’s old rifle was in the cupboard. She could shoot fairly well for a woman, so she hadn’t been afraid to live alone this past summer. Besides, in all these years there had never been any trouble or thievery in this peaceful farming area.

Again, she seemed to feel someone watching her. It was almost as if a man’s big hands reached out and stroked her bare shoulders, gradually pulled the thin chemise down to expose her breasts.

Sierra, you ninny! Why are you having crazy thoughts like this? Then she remembered the savage on the train late in the afternoon. He had stared at her in a way that made her feel as if he would like to put his hands all over her. . . .

She tossed the hairbrush into the trunk, closed it. Men. She supposed whatever their color, they were all alike. She had had such storybook ideas about marriage before Robert had deflowered her quickly and mechanically on their wedding night, then rolled over and gone to sleep.

She heard a sudden, surprised, squawk from the direction of the barn and ran to the window. Merciful heavens! Was there a varmint after her few remaining hens?

The mule brayed long and loud. Sierra hurried to get the rifle, checked to make sure it was loaded. The hens she could spare, but if the varmint was something big, like a bobcat, she was worried about the mule. She’d need that mule tomorrow. How she missed her old dog. She’d felt safe with Rex guarding the place, but he was dead now, too.

Still clutching the rifle, Sierra slipped on her shoes and reached for the kerosene lamp. She hesitated in the doorway, remembering the eerie feeling she’d had only moments before, and holding the lamp high, peered out toward the barn. Never had the night looked so black and ominous. The flickering lamp threw such a dim, small circle of light into the shadows.

When I get to the barn, she told herself, I’m going to find a possum or maybe a stray cat. Mercy, she was making too big a thing of this. Taking a deep breath for courage, Sierra checked the rifle again to make certain it was loaded, held her lamp high, and started forth.

Cholla looked around the edge of the barn door. By Usen, she had more courage than most women, she was

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...