- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

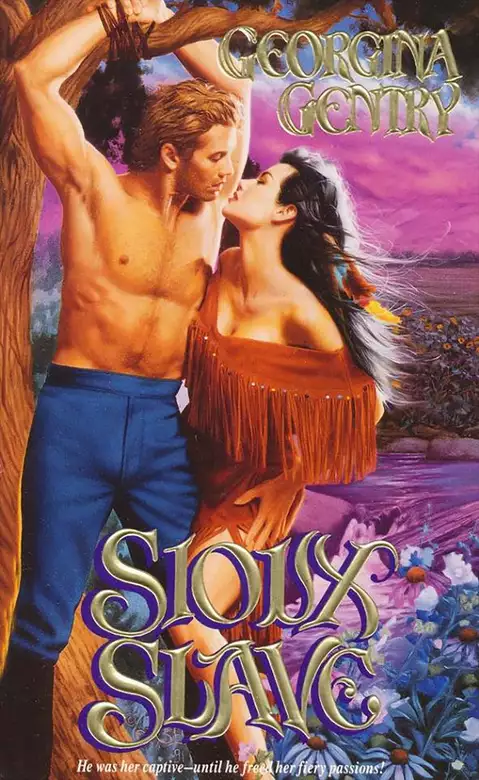

Georgina Gentry's historical romances are filled with fiery passion that is impossible to resist. . .or forget. She brings to life the exciting history and traditions of the American Indian in a way that makes her characters live forever in our imaginations. . .and our hearts! SIOUX SLAVE Widowed on her wedding day, Kimimila swore vengeance on the blue-coasts who had slain her betrothed. So when the village elders placed the fate of their yellow-haired captive in her hands, the beautiful Sioux maiden eagerly accepted the honor. But as she looked into her prisoner's sky-blue eyes, she could not find it in her heart to slay him. For what she felt for him was not the passion of hatred, but the desire a woman feels for the man who has stolen her heart and soul. Though he should have been her enemy, he soon became her lover. And as the heat of their desire burned through the Dakota nights, KImimila found her destiny in her white warrior's embrace.

Release date: May 16, 2014

Publisher: Zebra Books

Print pages: 447

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Sioux Slave

Georgina Gentry

In her tipi, Kimi sighed as she brushed her long black hair, holding the porcupine tail comb with her left hand. She listened to the drums and singing drifting through the camp. Her father had accepted the many ponies before he was killed in the last war party against their enemy the Crow. Kimi had voiced no objections, because Mato was a good hunter and her parents were old and had no other children to look after them.

Kimi reached for the bright ribbon from the trader to twist into her braids and pulled on the soft, beaded doeskin shift. She traced the outline of her spirit animal, the butterfly, in the beadwork. Kimimila. It meant “butterfly” in the Lakota language of the Seven Council Fires of the Teton Sioux.

Tonight she would be back in this lodge on the soft buffalo robes with the burly warrior called Mato: the Bear. She thought with regret how much older than she Mato was. Other warriors had made offers, but Mato was her father’s friend. And the ironic thing was, all the wealth of her ponies was gone. The hated wasicu, the white soldiers, had run them off months ago.

She hummed her spirit song absently, wondering what else she could do to delay, even as Wagnuka, (whose name meant “Woodpecker”) stuck her wrinkled face through the tipi flap. “Daughter, why are you so slow? The whole camp has already begun feasting and dancing.”

Did she dare say she didn’t want to go through with the marriage? No, she shook her head and steeled herself. Her family’s honor was at stake, and besides, she and her mother had no male relatives to hunt for them. Mato’s family had died of the white man’s spotted disease the last time it had swept through the Plains like mounted death. It could be worse; she could be a second wife in some warrior’s lodge.

“I am ready,” she said dutifully in Lakota and stepped outside. Although Wi, the sun, shone brightly, Tate, the wind, made the early spring day seem cool.

Across the circle of the camp fire, she saw Mato waiting, his homely face smiling as he saw her. The people surrounded her, teasing her, remarking what a great warrior he was, the women wishing her many children to replace the family Mato had lost. Everywhere in the Sihasapas camp, small children ran about laughing and playing, sniffing the good smells from the big kettles, knowing that today there would be feasting and dancing. There was no formal wedding ceremony among her people, but Mato had decided today would be a good time, since yesterday’s hunt had been successful and there was plenty of food.

Mato. He looked like a bear, all right. If only he weren’t so paunchy and almost old enough to be her father. She wished now that one of the younger warriors had been rich enough to offer more ponies. Her heart pounding with nervous dread at what she knew would come later today when the two were alone, Kimi forced herself to return his smile. For just a moment she glanced over at her mother and caught an expression that seemed uncertain and troubled. Had Wagnuka guessed her feelings? Was she wishing that there were another man for her only surviving child? Kimi was eighteen winters old, past time to be wed.

Kimi hardly remembered the festivities except sitting next to Mato and the way he ate huge bowls of food, the grease of the hot meat smearing his hands and broad, ugly face. He also had a bottle of the white man’s firewater that he had gotten from a fur trader. Whiskey. The whites had brought more trouble with them than just the Long Knives with their new forts.

Time passed. Kimi pretended not to see him glancing sideways at her, hoping to catch her eye so he could signal that they should sneak away to their tipi. He belched loudly and put one greasy hand on her knee.

Others noticed and nudged each other, the men exchanging knowing looks, the women giggling modestly behind their hands. Kimi felt the blood rush to her face, but she took a deep breath of the scent of burning brush from the big fire and pretended to watch the dancers. She intended to put this off as long as possible.

Even her mother was beginning to appear slightly embarrassed that her daughter still sat by the fire although drunken Mato had grown more bold with his hints. If they didn’t leave the celebration soon, Kimi would humiliate her mother. As a dutiful daughter, she must make the next step now. Her legs felt almost wooden under her as she rose.

Her man stumbled to his feet and followed her to the new lodge near her mother’s. Inside the light was dim.

“Woman, today you will begin making a fine son for me.” Mato belched and rubbed his hand across his greasy mouth before he took off his finely decorated shirt. He smelled of old fat and smoke from a hundred camp fires.

She stared at his bare chest, thinking how much more brown his skin was than hers. No words of love or tenderness, she thought, her mouth dry, her heart sinking. To the warrior, she was only a mare to be bred, and he was the stallion. What was it she had yearned for? She wasn’t even sure. Not that the plain, heavy man hadn’t been honest with Kimi. Mato had lost a whole family of children, and he expected her to replace them for him as rapidly as possible.

Now he hesitated, obviously waiting. She reached up to untie the drawstrings of her fine, soft doeskin, but her hands trembled so much that she couldn’t seem to untie it.

He smiled. “It is good that a maiden be modest the first time her man sees her body.”

Was it that? Kimi swallowed hard. There had been troubled nights when she had dreamed of a young man’s muscular, virile body warm against her own, his hot hands on her breasts and thighs, his wet mouth claiming hers.

Mato made a sound of impatience, reached out, took the strings from her fumbling hands, and untied it. Slowly the dress dropped to the ground, leaving her standing there naked, except for the medicine object hanging between her full breasts.

His expression changed and his eyes swept over her hungrily. He nodded approvingly. “Your skin is so light and soft,” he whispered, and his hands cupped her bare shoulders. “You are worth any gift a man would give to have you in his blankets, Kimimila.” His breath smelled sour with white man’s whiskey and she drew back.

“No, you have put me off long enough, even for a shy bride.” His voice sounded tense with lustful wanting, and he dug his fingers into her bare shoulders, pulling her closer. “I have lost all my family, but you are young; you will give me many fine sons. Perhaps instead of my dark skin, they will favor their mother, maybe even with eyes like hers.”

He pulled her up against him. Kimi felt the hard maleness through his breechcloth against her bare body, and she couldn’t control her trembling.

Mato laughed and hiccoughed. “Enough of this maidenly modesty. I intend to mount you continually until your ripe body swells with my child. I am not as young as some of the other braves, so I cannot humor you too long. By the time of deep snows, you will give me a son. This, your old father, Ptan, my friend, would expect from you.”

Yes, of course she must do this because it was as her old father Ptan (“Otter”) wanted. A Sioux woman could divorce her husband, maybe she might have even refused to marry her father’s friend, but she felt her family’s honor was at stake since she couldn’t return the ponies. Besides, at the moment Kimi didn’t see any better alternatives. Mato was a good hunter. She and her mother would be well fed.

Reminding herself of this, Kimi forced herself to relax against his bare chest as they stood there, his arms going around her roughly. His greasy hands felt hot on her bare back. She closed her eyes, wishing he were young and virile and that this first time was already over. Yet how different would it be with any other man? As a woman, she was not expected to do anything, she thought, except be there as the receptacle for his seed.

Her breasts felt crushed against his bare, brown chest as he held her against him, his mouth hot on her neck. Relax and let it happen, she reprimanded herself, but deep inside, some little independent part of her resisted.

“I have been waiting a long time to make you mine, Kimi.” His hands stroked her bare back.

From outside, there was sudden noise and confusion: the sounds of a horse galloping into camp, a warrior shouting, people yelling questions, dogs barking.

Mato pulled away from her and turned toward the racket, muttering, “What is happening?”

Kimi drew a sigh of relief that she had been given a short reprieve before this brave took that to which he was now entitled. “Had you better go see?”

The shouting outside continued. Mato frowned, listening to the Lakota words. “Something about a bluecoat patrol. Perhaps I had better find out.”

Turning, he picked up his buckskin shirt and pulled it on even as Kimi crossed her arms over her full breasts.

He grinned. “Later tonight we will continue and there is not an inch of you that my body and mouth won’t know, so do not be so shy before me.” He reached for his weapons. “For now, I had better see what this trouble with the wasicu is about.”

Mato strode through the tipi flap as she breathed a little prayer of thanks to Wakan Tanka, and reached for her dress. Trouble with the bluecoats had slowed over the long cold winter as the snow fell across the desolate plains and the sacred Pa Sapa the whites called the Black Hills to the south. A war party might count coup or steal a few horses from the Long Knives patrol, but the main thing was to make sure the soldiers didn’t find the camp.

Kimi dressed and went outside to stand by her mother. Already in the spring afternoon warriors were painting themselves and their ponies, readying their weapons. Mato galloped up, weaving slightly on the back of his pinto pony.

An old man protested. “I feel uneasy about this war party. There has not been proper time given to making medicine.”

Mato smiled and caused his mount to rear, its china eyes rolling as it danced and snorted. Red paint handprints on its white shoulders signified that its owner had killed an enemy in hand-to-hand combat. Mato himself wore a warbonnet with trailing eagle feathers, each one showing a brave deed or coup counted. He had changed into a buckskin shirt decorated with enemy hair.

Wagnuka’s old face furrowed with worry as she glanced at her daughter. “White soldiers always are looking for young women to steal and carry back to their fort to amuse themselves. Perhaps they come looking for Kimimila.”

One of the other warriors shook his head. “I think they seek nothing in particular,” he said in Lakota. “Long Knives forever go on patrols. They just wander in circles unable to follow the track of even a big buffalo herd.”

Mato held up his rifle reassuringly. “My woman need not be afraid; Sioux warriors will not let the soldiers find this camp, rape and burn and kill as they did our Cheyenne brothers at Sand Creek last winter. We will die rather than allow that to happen to our people!”

The other braves set up a yelp of agreement.

One Eye, Mato’s friend, frowned. He, too, was a Shirt Wearer. One Eye might have been handsome except that he had lost the sight in his right eye fighting the Crow enemy, and now wore a patch over it made from a scrap of red blanket. “Mato, my friend, since you have just taken a bride, you have no obligation to go on this war party.”

The Bear laughed in drunken derision. “I should stay and enjoy a woman, safe in my blankets while my friends gain honors and count coup on the wasicu? There will be horses to steal, scalps to take.” He grinned drunkenly at Kimi. “Should I go, woman?”

Kimi hesitated, dreading that time when he would take her virginity. “Do whatever your heart tells you to do.”

Mato nodded with pleased approval. “Spoken like a proper wife. There will be many coup to count today and war honors to relate around the fires by our sons.” He wheeled his horse around. “Kimi, I will bring you back some shiny brass buttons, some blue cloth to decorate yourself with.”

Even then Kimi thought if she begged him not to go, her new husband might change his mind about accompanying the war party. She hesitated. Mato was stubborn. Perhaps he would not listen anyway to a mere woman while his thoughts were on war honors and fresh scalps to show off at a victory celebration. Already they were hearing reports of the coups counted by warriors such as Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull, and Red Cloud among the other clans of the Teton Sioux. Kimi pushed her misgivings from her mind. Countless times she had watched her father ride out with the war parties. The Seven Council Fires of the Teton Sioux had many enemies. They had fought against the Snakes, the ’Rees, the Crow and the Pawnee who raided and killed her people at every opportunity.

Years ago their enemies had begun to scout for the white wagon trains that crossed the prairies, and finally for the soldiers who seemed to push farther and farther into the sacred hills of the Pa Sapa and the buffalo country that belonged to the mighty Sioux by right of conquest.

The women and children gathered to watch as the war party rode out, cheered on by old men too feeble to ride the war trail anymore and young boys who had not yet become men. The women made the trilling sound to encourage the warriors and sent them galloping out of camp.

“Wakan Tanka nici un,” she whispered in Lakota. Good-bye and may the Great Spirit go with you and guide you. Kimi stared after them a long moment, feeling both proud that her man was one of the bravest of the warriors, even though he was not as young as some of the others. Yet her pride was mixed with relief and then guilt that it would postpone that time before Mato took her virginity and really made her his woman.

The women broke up into little groups, talking of past war parties and booty that had been theirs. This evening when the warriors returned, there would be much feasting and gathering around the fire while the braves recounted each coup and happening. Old warriors then would tell of past glorious times when the Sioux were the undisputed rulers of the Plains; when they and their allies, the Cheyenne and the Arapaho, the Comanche and Kiowa, controlled the whole prairie from the Land of the Grandmother the whites called Canada to the Rio Grande of the Mexicans. Not so long ago, enemies trembled at the mere mention of their names. Now their enemies rode boldly for the gold of the white soldiers who had invaded Sioux domain and acted as if they might even dare to stay permanently, although the white chiefs denied it.

Absently humming her spirit song, Kimi reached up to touch the small fetish hanging between her breasts. Her mother had never told her where she had gotten it, but it must possess powerful spirit magic because it was such shiny metal like Wakan Tanka’s own sun, Wi.

There was always work to do in the camp, and Kimi tried to help women burdened with children or old people too frail to dry meat or scrape a hide. She went about her chores and looked forward to the evening’s victory celebration, even if it must be followed by Mato’s thick body lying on her small one. Perhaps if she closed her eyes when he took her, she could pretend he was the strong, virile warrior of her troubled dreams.

Why had he been unlucky enough to end up stationed at Fort Rice, Dakota Territory? This was no place for a Southern aristocrat! Swearing under his breath, Randolph Erikson shifted his weight in his saddle as the patrol rode across the bleak prairie.

“Because it was either volunteer to join the Union Army or die in that hellhole of a Yankee prison camp,” he drawled aloud as he took off his hat and brushed his blond hair back.

“Huh? Lieutenant, did you say somethin’?” The rednecked lout riding next to him glanced over, startled.

“I’m not a lieutenant anymore, soldier,” Rand drawled. “The damn Yankees wouldn’t let any of us Confederate officers keep our rank.”

The other soldier guffawed good-naturedly and spat tobacco juice that dribbled down his chin and onto his saddle. “Now you’ve learned how poor white trash lives, I reckon, with not even one slave to polish your boots. If I’d had all that, I’d have fought to keep it, too. I’ll bet you was a purty sight in your fancy uniform at all the balls and soirées.”

Rand didn’t answer, concentrating instead on the others of the patrol riding ahead of them across the endless prairie. “Reckon I’ve changed a little since being in Point Lookout. After that miserable trip here and all these months at Fort Rice, reckon we had it good in that Yankee prison and didn’t know it.”

The other nodded in understanding. “Fort ‘Lice’ would be a better name.”

Seven months in Dakota Territory. Maybe he had changed a little from the arrogant, spoiled plantation owner’s son he was. Rand blinked pale blue eyes against the afternoon sun, not wanting to think about his miserable existence since he’d been captured.

Instead, he remembered olden, golden days before the war on his parent’s Kentucky estate. With money and social position, Randolph Erikson’s biggest worry was whether the fox hunt might be called off because of rain or if he might have to choose between a ball at the capitol or an elegant dinner at the nearby Carstairs’ estate.

The other sneered. “What did a young dandy like you do in the war?”

Rand flexed his wide shoulders. “I was a liaison for the colonel, carrying messages. I reckon I never did much real fighting.”

The other spat tobacco juice again and wiped his mouth with the back of his hand. “I knowed you was quality the first time I laid eyes on you at the prison: hatin’ to have to mix with poor redneck trash, swaggerin’ when you walked. God, I don’t even know what I was doin’ in this war. I never had me no money to own no slaves.”

“Oh, we own slaves, I don’t even know how many,” Rand shrugged, “but you know Kentucky was a border state, didn’t go with the Confederacy, and Lincoln only freed the slaves in the rebelling states.”

The other looked at him, scratched his mustache. “Then what the hell was you doin’ fightin’ anyways?”

“I reckon my answer is about as foolish as yours,” Rand admitted as they rode through the late afternoon. “I thought it would be a grand adventure.”

The other man snorted with laughter. “Reckon you found out different, didn’t you?”

“Yes, I surely did.” Rand cursed softly under his breath, remembering how he had expected this war to be a lark, an adventure to amuse the ladies with over drinks on Randolph Hall’s veranda. He had never thought any further than how dashing he would look in the gray uniform. Father had tried to talk him out of it, but Mother, with her deep Southern sympathies, and his fiancee, Lenore Carstairs, had secretly encouraged him. After all, it was going to be a short war that the Confederates would win out of sheer gallantry. Lenore had said he looked so handsome in the uniform, and she gave a ball in his honor.

Instead the great adventure had turned out to be hell with the hinges off. The young blueblood had never before known hunger or pain or terror such he had experienced. The irony of it all was that he was captured carrying a dispatch in an area that was supposed to be controlled by the Confederates.

Rand flexed his shoulders again, trying to find a comfortable position in the saddle. Lieutenant Colonel Dimon led the patrol across the gray-green buffalo grass toward a small creek where stunted willows grew. Rand had lost track of where they were; somewhere near the Knife River, maybe. At least they would get a minute’s rest while they watered the horses.

“Hey, Rand, you suppose there’s any Injuns out here? We ain’t seen any, and we’re ridden clean through that area where we might have seen Hunkpapas and Sans Arcs.”

“Maybe we’ll be lucky and not see any. Dimon’s a glory hunter, but medals don’t mean much to me.”

The other man shuddered. “After what them Eastern Sioux did to them settlers in Minnesota, I’ve had some nightmares about bein’ taken alive.”

Taken alive. Rand didn’t want to think about it. Three years ago, after years of starvation and mistreatment, the Santee Sioux had revolted. When it was over, eight hundred white people lay dead. In the largest mass execution in American history, the government had hanged thirty-eight Sioux warriors.

Rand frowned. “The Yankees forgot to tell us about that possibility when they were looking for volunteers.”

“Do you suppose the war is over yet so we can go home?’ The last we heard, it looked like Lee was nigh surrounded.”

“Who knows?” Rand shrugged. “If Dimon knew, he wouldn’t tell us; afraid we’d all desert and leave.”

“Why didn’t your rich folks bribe someone and get you out of Point Lookout?”

Rand made a noncommittal grunt. In truth, he’d sent a couple of messages and hadn’t gotten any answers. Maybe his mail wasn’t getting through. Now that he was stuck in the Dakotas, mail was almost impossible to send and receive anyway. Maybe that was why he’d heard so little from Lenore.

“Rich boy, what you gonna do when the war’s over?”

Rand didn’t bother to answer the ignorant lout. What was he going to do? As expected, he’d go back to Kentucky, marry the Carstairs heiress and return to the aimless, idle life that being one of the local gentry afforded him. Somehow now that he thought about it, that life didn’t seem as appealing as it once had. As much as he hated to admit it, the freedom of this trackless wilderness and wild, windswept prairie was beginning to grow on him. He was even beginning to feel a little empathy for the Indians, who, like the Southerners, were fighting against invaders and a changing way of life.

They rode toward the thicket along the creek. Rand thought how a fine cheroot and a tumbler of good Kentucky bourbon would taste about now on the spacious flagstone veranda of his family plantation. Beautiful, dark-haired Lenore Carstairs might be there to visit.

Maybe it was that sixth sense that some men seem to have that sent a sudden warning prickle up Rand’s neck as they rode into the willows. Whatever it was, he cried out a sudden alarm and reined in his rearing bay mount, even as the brush ahead of them seemed to explode with gunshots. Startled horses neighed and reared as men around him toppled from their saddles.

Young Colonel Dimon shouted orders, but no one seemed to hear him over the thunder of guns. Horses screamed and kicked while riders fought to control the terrified mounts. The men appeared ready to panic and retreat in disorder. Without even thinking about it, Rand found himself coolly shouting orders. He might be considered an arrogant and privileged dandy, Rand thought grimly as he directed the men around him to dismount, seek cover, but he was no coward.

“Get down!” Rand shouted again, then swore softly under his breath at that fool young colonel leading his patrol into this. Dimon was not yet twenty-five, and he lacked common sense. Rand was not much older himself; he wondered now if he would live to be a day older than that. “Don’t give them a target! Keep calm, men! Make every shot count!”

He hit the ground, crawling through the damp dirt with his rifle to a vantage point behind a dead log. The trooper who had ridden next to him crawled up close. “What do we do, Rand?”

He started to answer even as the man screamed out. The soldier looked at him with wide eyes, tobacco juice dripping from his mouth and blood pumping with each beat of his heart through the ragged hole in his blue uniform and into the new green grass of spring. Rand reached to help him, saw it was no use. The redneck rebel who had tried vainly to save his life by joining up with the Yankees had lost his gamble.

Around Rand men reloaded and fired, the scent of blood and burnt powder so thick it gagged and choked him. The little patrol was outnumbered; Rand had been in battle enough to realize that. He aimed, pulled the trigger and missed. The corporal nearby brought down an older, war-painted brave wearing an eagle-feather warbonnet from his pinto pony. That Sioux looked big as a bear, Rand thought. Would he be next to spill his life blood upon the ground?

Gunshots and shouts roared in his ears. The smell of acrid powder and warm blood hung on the late afternoon air. All around him men screamed as they fell. Rand flexed his shoulders and swore silently. Had he come all this way from Kentucky only to die in a faraway wilderness against red men who were only trying to defend their land against white invaders?

All that mattered now was staying alive. Rand reloaded his rifle. A cavalry horse screamed and half reared as it was hit, and then went down. Somewhere over the noise and screams and shots, Rand heard the bugler blow retreat. He rose from the ground, looking for his horse.

A pain like a red-hot saber burned through his thigh. He was hit! Rand fell, cursing, grabbing at his leg, shouting at the patrol not to leave him. In the smoke it was hard to see anything. Over the noise and shouts, the soldiers seemed intent only on saving their own lives, scrambling for the few horses that hadn’t bolted away or been killed.

Rand shouted for help again, but already he saw the soldiers were mounting up in panicked disorder, the Sioux warriors shrieking triumphantly as they crossed through the willows in pursuit.

The old timers always said it was better to kill yourself than be taken alive by the Indians to be tortured to death. He was out of ammunition and fast losing consciousness from pain and loss of blood. With sheer willpower, Rand struggled to hobble toward the retreating soldiers. He gripped his thigh, trying vainly to staunch the hot blood running between his fingers. Ironic somehow, he thought weakly. He’d been at Fort Rice since last autumn and had never killed or wounded a single Indian, yet he would die here, a victim of their revenge against white Yankees. He would have been better to have stayed in the Yankee prison with the other captured Confederates.

The soldiers had mounted up, were galloping away as Rand tried to hobble after them, but the remaining horses had bolted. Out of ammunition, all he could do was hide. Rand burrowed down behind some low bushes, listening to the warriors moving through the brush.

He took off his gun belt and used it to make an awkward tourniquet. It would be dark in a couple of hours. Maybe if he lay very still the braves wouldn’t find him. At night, he might have a chance, although it was a long way back to the fort. He wouldn’t think about that. He’d think about staying alive.

In the past long winter, out of sheer boredom, he’d learned a little of the Lakota language from an old drunken Sioux who hung around the fort. He wished now he hadn’t. He could understand enough of the shouts to know the warriors were looking for more than scalps and extra guns. They were looking for revenge.

Abruptly, one of the painted braves stood over him, his painted face grinning with triumph. Over one eye, he wore a patch made of a scrap of red fabric. “Hoka hey! I have found one of their wounded!”

All Rand could do was lie there and look up at him, hoping the brave meant to kill him cleanly with that big lance he carried.

The warrior shouted to the others and gestured. “The bluecoats have killed my friend, Mato! We will take this yellow-haired captive back to camp for Mato’s widow to avenge his death!”

The warriors were returning. Kimi, working on a pair of beaded moccasins in her tipi, heard shouting throughout the camp. She sighed as she laid her work aside and looked toward the blankets. What she had managed to delay must soon take place unless Mato was too weary from the fight or there was a great victory to celebrate. She could only hope he would drink enough of the white man’s liquid fire that he would not bother her tonight.

A Sioux woman could leave her man; it was part of Sioux custom. However, there was no other man in this camp that had turned her head. Maybe she was better off to be Mato’s only wife rather than the second wife of another warrior. He was a good man, just a little old. She would try to be a dutiful wife to him and produce a son quickly. That would insure that her mother would be well cared for.

Kimi paused as she stood up, feeling a sense of foreboding because she didn’t hear shouting or victorious trilling from the people outside. She reached to touch her spirit charm hanging around her neck before leaving her tipi to stand in the twilight with her mother. Together they watched the war party riding slowly into view.

Aihee! Yes, there must be something wrong; the warriors were not shouting triumphantly and galloping their horses in the way they should be if all had gone well. No, the men rode with their shoulders slumped and several looked bloody and wounded. None wore the customary black victory paint.

Her mother made a small noise of alarm. “One is missing. I thought more rode out.”

Around them, a murmur went through the crowd that waited in the big circle as they, too, seemed to realize something was wrong. Mato. She didn’t see him among the riders.

Kimi put her left hand to her mouth, guilt sweeping over her.

Abruptly, her mother cried out and a sympathetic murmur ran through the women a

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...