- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

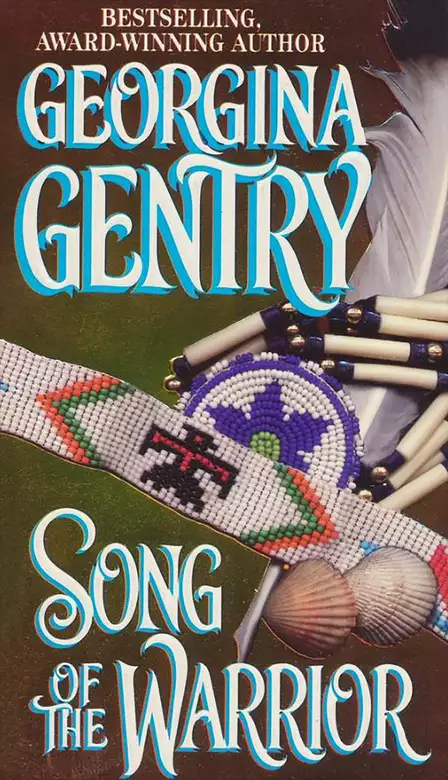

Synopsis

Slender, dark-haired Willow had been sent East as a child. Now, she returned to her mother's people, the Nez Perce of the Great Northwest, to teach them the white man's ways. The magnificent full-blooded warrior Bear had been raised to be proud, wild and free. His meeting with Willow would set two lives on a collision course- and two hearts aflame with forbidden desire. For the year was 1877, a time of tragedy and change. Pursued by cavalry, forced into impassable terrain, Bear's band of Nez Perce would soon be fleeing for their lives. With them would be Willow, bound by her unshakable devotion to Bear, yet destined to be torn from his arms by another man's treachery. Swept up on an odyssey of courage and passion, it would take all her strength and love to survive. . . and to save them both. The award-winning author of novels set in the Old West, Georgina Gentry is one of America's favorite romance writers. Vibrant with authentic history, shimmering with tender emotion, SONG OF THE WARRIOR is her most moving, sensual and unforgettable story yet. "ONE OF THE FINEST WRITERS OF THE DECADE!" - Romantic Times

Release date: May 16, 2014

Publisher: Zebra Books

Print pages: 510

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Song Of The Warrior

Georgina Gentry

Willow knew he was trouble the moment she saw him. She paused as she stepped from the stagecoach and stared at the big Indian on the Appaloosa stallion coming down the muddy street. He reined in, looked her over. Was that just the slightest derisive sneer on his rugged, dark face?

Willow glared back. Blanket Indian, she thought, too primitive and set in his ways to accept civilization and change as she had done. For only a moment, he regarded her, then seemed to dismiss her with a shrug of his wide, buckskin-clad shoulders, nudged his horse and rode on down the settlement’s muddy road.

The unkempt stage driver cleared his throat. “Ma’am, ain’t this your valise?”

“What?” Startled, Willow returned her attention to the man at her elbow. “Why, yes.”

She took the small bag, brushed the dust from her simple green traveling dress and stared after the virile warrior disappearing down the muddy street. “Just who is that?”

“Hohots,” the driver grunted, following her stare. “Most likely in town lookin’ for his younger brother.”

Hohots. Grizzly Bear. Willow struggled to remember the Nez Perce word. These were her people, but she had been gone so many of her eighteen years that she had forgotten much of the language and had been struggling to relearn it. In the past weeks and on the train west, she had studied hard. “He must be named for his disposition.”

The driver laughed, rubbed his straggly mustache. “No man would daresay that to Bear’s face, ma‘am, much less a slip of a girl like you. Somebody meetin’ you, Miss?”

“Why, yes, the Reverend Harlow.” She looked around at the hustle and bustle of the tiny settlement. She had been born in the Nez Perce country, but not raised here.

“You’re that little gal the preacher sent away to school years ago, ain’t you? Everyone’s heerd of you.” He stared down at her with unabashed curiosity.

Willow nodded. “I’ve been in Boston and hardly remember anything at all about this country.”

“Wouldn’t have recognized it no ways. Gold fever’s spread bad the last few years.” He took off his battered hat, ran his hand through his straggly hair. “Then there’s settlers movin’ in all over the place.”

“The Nez Perce won’t like that,” Willow protested.

The driver shrugged as he climbed back up to the top of the stage. “Maybe not, but that’s the army’s problem.”

Willow looked after the big warrior on the Appaloosa horse fading into the distance. “Surely some of the Nez Perce realize that walking the White Man’s Road is the only smart thing to do; that’s why I’m here; to teach.”

The driver turned to follow her look. “Beggin’ your pardon, Miss, but ain’t no little thing like you gonna have much influence on the Bear. He’s an independent cuss, and one of Joseph’s war leaders.”

Willow felt her face burn. “We’ll see. Surely he won’t care if I try to teach his children to read and write.”

“You’re arrivin’ at a time of trouble, I’m afeared.” The driver bit off a chaw of tobacco. “Army’s tryin’ to persuade the Injuns to move to a smaller reservation.” He looked over the tall, slender girl and seemed to realized Willow must be part-Indian. “ ‘S’cuse me, ma’am. I meant no offense.”

“None meant, none taken,” Willow forced herself to smile politely. She sometimes forgot about the prejudice while she was at boarding school at Miss Priddy’s in Boston because she was more than half-white, but here in the great Northwest frontier, she might have to face it again. The driver touched the brim of his hat politely in dismissal, cracked his whip and the grimy coach pulled away, leaving Willow with her one small bag standing on the wooden sidewalk.

Just where was her elderly guardian? Would she know Reverend Harlow when she saw him? Uneasily, Willow looked around. It was almost dusk and like any frontier settlement, Saturday night wasn’t the best time for an unescorted woman, even a respectable one to be on the streets alone.

She heard drunken laughter, turned to see three young braves stagger out from between two buildings. Drunk, she thought with ill-concealed disgust. She would pretend not to notice them.

They spoke to one another in Nez Perce. “Hey, Raven, koiimize! Hurry! We had better go before your brother comes looking for you.”

The handsome, tall one snorted and leaned against a post. “I do as I please. Now, what is this pretty thing?”

Willow could feel him staring at her in undisguised admiration. She remembered more of their language than she had expected, but she decided to pretend ignorance. If she ignored them, maybe they would go away.

“That’s a white girl, Raven,” the other brave cautioned. “Let her be; men have been killed for even talking to a white girl. Your brother—”

“I’m sick of always hearing about the big, brave Bear,” Raven snapped. “Besides, he’s at the camp, he won’t know we’ve had a little whiskey.”

“No, he isn’t,” Willow blurted in Nez Perce before she thought, “he’s in town and looking for you.”

The three stared at her, wide-eyed. She felt her face flush under their stares, especially the handsome Raven.

“So,” he said, grinning, “how come you to speak our language, white girl?”

His friend grabbed his arm. “Let us go, Raven, before we get into trouble.”

The young man shrugged the hand away. “You two go on back to camp, I would speak with this girl.”

The two braves fled up the alley while the one called Raven leaned against a post and stared at her insolently. “You did not answer me.”

Willow fumbled for the half-forgotten Nez Perce words. “You’re drunk,” she answered in his language, surprising herself at how many words came back to her now, “you shame your people.”

He came closer. “You have eyes the color of new grass, but you are not white.”

Willow looked up at him. He was taller than she, although she was tall for a girl, but he was not much older. “Go back to camp, before you get into trouble.”

“Now you sound like my big brother.” He grinned at her. “Since when do women give orders to warriors?”

“You are not a warrior,” she snapped back, “you are scarcely more than a boy and a drunken one at that.”

“Ah, now I know who you are; everyone says you were returning.” Raven nodded and swayed on his feet in the dusk of the evening. “You are that mixed-blood chit the preacher sent to be educated. I’m surprised you still speak the language of us ignorant savages.”

Willow felt her face burn at his retort. “It is not a bad thing to be educated and civilized.”

“If you say so.” He grinned with white teeth and she thought he seemed very handsome and reckless. “I forget what they call you.”

“Takseen.” It was Nez Perce for Willow. “I will teach our people. The children must learn the ways of the white man so we can live among them in peace.”

“Is peace worth our freedom?”

Willow drew herself up proudly. “I will not debate with a drunken boy. Perhaps it is best to give up the old ways.”

“I am older than you!” He swayed on his feet. “You had better not let my brother hear you say we should trade our freedom; he trusts no whites.”

This discussion was going nowhere. There were no people to be seen now as suppertime neared. She turned her back and looked up and down the road, wondering what had happened to her guardian?

The handsome youth stumbled toward her. “Takseen, why do you loiter on the street like a white man’s whore? Does no one meet you?”

She whirled on him. “Go away! No doubt Reverend Harlow has been delayed.”

“I will stay and protect you then,” he announced grandly.

“You are drunk! Go back to camp before you get in trouble,” Willow said. She did not want to be standing here if his older brother came along, and drunken Indians might not be dealt with kindly by shoyapees, white men.

A burly, bearded frontiersman came out of the saloon next door and paused to light a cigar, stared at the pair. He wore dirty buckskins and might have been in his middle forties, it was hard to tell with the livid scar across his forehead. “Ma‘am, is that Injun buck annoyin’ you?” he asked in English. “Deek Tanner, army scout at your service.”

She tried not to stare at the horrid scar, tangled hair and beard. “No, he’s not bothering me; he’s just had a little too much to drink; that’s all.”

The scout scratched his gray-streaked beard, stared hard at her. “Why, you ain’t no white lady; you’re just some half-breed.”

“Let her alone!” Raven protested.

“Raven, don’t!” Willow motioned him off. “I can handle this.”

Tanner leered at her. “Hey, honey, if you’re lookin’ for a man, not a boy, let’s talk; I got money.” He sauntered closer in the growing dusk and Willow was horrified to realize there were lice in his dirty beard.

“I’m not a boy. Let her alone.” Raven took a step and swayed a little.

The white man swore and the muscles rippled in his wide shoulders and long arms. “Get outa my way, you uppity redskin bastard. No drunk Injun kid is gonna give Deek Tanner orders.”

Willow’s heart began to hammer as she looked up and down the street. At suppertime and almost dark, there didn’t seem to be anyone around who could help. She drew herself up with haughty dignity. “Look, anyone can see he’s drunk and no match for you. Let him alone.”

The terrible scar on Deek’s forehead seemed to gleam white in his ugly face as he grinned at her. “Sure. Now, honey, you just come up to my room with me and I won’t make no trouble for the kid.”

He reached to grab her arm and Raven lunged for him. “I told you to leave her alone, white man!” He struck at Deek, but the big scout sidestepped, then struck Raven in the face with his fist, sending him falling back against the hitching rail.

The boy fell, but even before he hit the wooden sidewalk, Deek was on him, picking him up and shaking him like a feisty pup, hitting him again. “I tole you, boy, now I’m gonna teach you to listen when a white man talks to you.”

Raven tried to protect himself, but even if he hadn’t been drunk, he was no match for the burly frontiersman.

“Don’t hit him, can’t you see he’s just a boy?” Willow grabbed Deek’s arm, tried to hold him back, but he shook her off, grinning. “Squaw, I’ll get back to you when I teach this redskin a lesson!” He hit Raven again.

She was only vaguely aware of the sound of galloping hooves but abruptly, the big warrior, Bear, came off his running horse and into the fray. “You are brave, white scout, with a boy. Let us see what you can do with a man!”

Even as Willow watched, Bear whirled the scout around, hit him hard. Deek stumbled backward against the storefront, blood running from his mouth and into his gray-streaked beard. Bellowing like a wounded bull, the white man charged at the warrior, who sidestepped easily and tripped the heavier man. Deek Tanner went down with a crash, swearing mightily.

Willow saw faces at windows, but everyone looked as if they hesitated to get involved. The two men meshed and fought as Willow knelt by Raven’s side. “Are you all right?”

He brushed her hand away and attempted to stand even as his big brother hit Deek Tanner again. Easily, Bear lifted the scout across his knee and Deek screamed for mercy, “Oh, God! Don’t break my back! Please, I don’t mean no harm!”

“Don’t kill him!” Willow shrieked in the Nez Perce language and grabbed Bear’s broad shoulder. “You savage, don’t kill him!”

At that, Bear looked at her, hesitated, threw the man to one side as if he were a scrap of garbage. She abruptly felt intimidated by the Indian and stepped backward, stumbled over her valise, and landed in a sitting position on the wooden sidewalk.

Whimpering, Deek Tanner crawled away. Now the warrior towered over her, glaring. “You speak our language, yet you call me a savage?” He didn’t wait for an answer as he grabbed her hand, pulled her to her feet. For a split second, they stood looking into each other’s eyes. He had such big hands, she thought.

He let go of her, dismissed her with a shrug and turned on his brother. “Must you always be so irresponsible?”

“He was attempting to help me,” Willow snapped, annoyed with herself for letting him intimidate her. Bear was bigger and older than his brother, perhaps in his late twenties or early thirties. Maybe some might think he wasn’t as handsome as Raven, but his raw virility and masculinity told her why men would fear this Nez Perce brave.

Bear’s lip curled in disdain as he glanced from Willow toward the whimpering scout crawling across the wooden sidewalk. “Good thing for you both I came along. You play the mimillu.”

Raven looked crestfallen. “I am not a fool. You shame me before the girl,” he muttered.

“Saus! Quiet! You shame yourself, little brother,” Bear shot back. “Let the whites protect their own women.” He helped the younger man up with a gentle hand.

She felt both stung and sorry for Raven’s humiliation. “I am part-Nez Perce myself.”

Bear studied her as he draped Raven’s arm over his own broad shoulder so he could assist him. “I see that now, but why do you dress like a white? You reject your own traditions for theirs?”

“We must all learn to live like them, not like savages.” She brought her chin up proudly.

“Some of us won’t,” Bear said and his voice was cold. “I know who you are now; our people have all heard of the Russian trapper’s half-breed whelp.”

“Bear,” Raven protested, “don’t talk to her like that.”

“She called me a savage after I came into this fight to save you both.” He glared from one to the other.

“I-I’m sorry.” Willow bent her head. “I thought you might kill the scout and it would have meant trouble.”

He gave a disdainful snort. “You dare to lecture a warrior? Go back East, fake white girl, we don’t need you!” Hefting his brother in his powerful arms, Bear headed toward the big Appaloosa stallion.

He was the very thing she was trying to change. “I will not go back East,” she yelled after him. “I come to teach the children the white man’s ways, teach them to read—”

“Perhaps that is good,” Bear shouted over his shoulder as he helped his brother up on his horse, “Amitiz, we go now,” he said in his own language. “Maybe you can teach us the trickery of the whites so we can hold our own when they cheat us! Taz alago.”

She didn’t return his “goodbye.” There was no dealing with men like this one, Willow thought as with annoyance she watched them ride out. The Indian culture must be replaced with the superior one of the whites, so the Nez Perce could survive; that had been drummed into her. Men like Bear could never be changed. She stared after him, angry at his obstinate rudeness as she dusted the sidewalk dirt from her skirt. Yet, if he hadn’t come along, she and Raven would have had more trouble than they could have handled.

A buggy rounded the corner, and she recognized the elderly driver from the old daguerreotype. Willow smiled as he reined in. “Reverend Harlow?”

“Ah, Willow, my dear girl.” He looked to be at least seventy, maybe older; white-haired and dressed in rusty black. The smile was out of place in his thin, grim face. “I’m sorry I was late, but there was a meeting; trouble with the Indians, you know.” He climbed down and held her out at arm’s length. “I don’t remember you being so pretty; too bad dear Charity didn’t live to see you all grown up; she would have been so proud of the ragged child we took in when no one else wanted you.”

“I’m sorry I don’t remember much about anything, but I do appreciate all your trouble,” Willow apologized as she got into the buggy and Reverend Harlow picked up her valise, put it in back.

“I’m glad you remember how obligated you ought to be, young lady. Cast your bread upon the waters, my Charity used to say. I’ve been attempting to teach these heathen about Ahkinkene kia, the Happy Hereafter, but their idea of heaven is their Wallowa Valley.”

The Wallowa. Land of the Winding Waters. In her vague memory, it was as lovely as heaven ever dared to be.

The old man must have taken her silence for dismay. “You won’t find it easy, I’m afraid; there’s so much of the Lord’s work to be done among these savages.”

She winced at the word, remembering Bear’s accusation. “I’m eager to begin teaching the children.”

He climbed into the buggy. “This is going to be as I always dreamed it would be when I convinced the missionary board to send you back East to school and prevailed on Miss Priddy to lower the tuition. You know I have wealthy relatives in Boston, the Van Schuylers, who are patrons of the school, or you would not have been accepted.”

“I am grateful,” Willow said automatically and tried not to clench her teeth. In truth, she had not been all that happy at Miss Priddy’s snobby school. The patronizing, condescending attitude of the rich girls toward the charity case had been difficult to deal with.

“Good. We must all do our part to change these heathens.” He picked up the reins and clucked to the old bay gelding. “I have a little parsonage on the edge of the settlement; not much, but then, I’ve filed on some good land that I hope to build a house on later.”

“Nez Perce land?” Willow asked.

“Of course. Oh, they don’t know or care anything about owning land; idea’s foreign to them. The sooner we get them corraled on reservations, teach them the white man’s way so they’ll be peaceable, the sooner we’ll be able to bring in more settlers. This fine land is too good to waste on roaming savages.”

Willow felt a trifle uneasy as they drove away. “There’s so many settlers here now; so much different than I remember as a child.”

“Oh, not nearly as many as there’s going to be,” the black-suited missionary assured her with satisfaction. “It’s the Lord’s will that we teach these brown heathens so they’ll stop their warlike ways and settle down.”

“The Nez Perce were never warlike,” Willow protested. “They’ve lived at peace with the whites since Lewis and Clark explored this area almost seventy years ago.”

His stern face frowned even more. “You’ve been gone all these years, my dear child, so you don’t know what trouble we’ve had. The ingrates seem to resent whites coming in, trying to put this land to good use, and of course, there’s the gold prospectors. I’ve done what I can, but they’re just such stubborn, ignorant savages.”

“I met two of them,” she blurted, “one called Bear—”

“He’s one of the worst,” the reverend snapped. “The nontreaty Nez Perce are insisting that they signed no treaty and won’t move to the new reservation.”

“So what will happen?”

He smiled. “Now, Willow, don’t fret yourself. I think if the army just lets them know the whites mean business, they’ll back down.”

She thought about Bear. He didn’t seem the type to back down if he had to face the whole U.S. Army. “I met Bear’s brother, too.”

“Raven?” Reverend Harlow sniffed. “Irresponsible young scamp about your age, I’d say. If it weren’t for his big brother, he’d be in a lot more trouble. Some of the things the young bucks have learned from our civilization are sloth and the love of liquor.”

“Maybe they’re that way because the whites have run the game off and fished out the streams and there’s not much for them to do anymore.”

“We can change all that,” the old man said with enthusiasm, “if we can ever teach them to farm, we can put them to labor for white farmers. You know the devil finds work for idle hands.”

“The Nez Perce aren’t farmers and never were,” Willow protested, “they hunt and fish.”

“Now, my dear, how would you remember any of that? After all, you’ve been away to school all these years. It’s lucky I was around when that drunken squaw deserted you; to say nothing of that worthless trapper who fathered you.”

Willow felt guilty and ashamed. “I-I’m sorry,” she said, “I’m just not sure what success the Nez Perce would have at farming.”

Well, it’s high time they learned,” Reverend Harlow snapped. “I could use some good hands on the piece I’ve got. Anyway, if they aren’t going to farm it, why do they need all that land?”

“Just to roam on? No, of course you’re right.”

He nodded in approval. “None of us have done much good with them, but you’re one of them, Willow, my dear, and you know what the Good Book says about ‘raise up a child in the way he should go.’ ”

“You’re right; I might be able to change the children anyway.” In her own mind, she wondered suddenly if the white preacher saw her as just some noble experiment.

“Peace and prosperity for the whole Northwest.” He smiled at her. “I have prayed for a way to do God’s work, and now between us, we’ll do much to save the Nez Perce from themselves. That Chief Joseph and his stubborn ilk like Bear won’t listen to reason.”

Bear. She remembered the way he had looked at her and the way it had sent an unaccustomed feeling running through her when his hard hand closed over her small one. He was a man, arrogant and sure of himself when she had been accustomed to dealing with mere boys her own age. “I presume this Bear has a lot of influence among his people?”

Reverend Harlow nodded. “His father was a chief and he’s one of Joseph’s confidants.”

“Then it’s settled,” Willow said with satisfaction, “I’ll get on his good side somehow; maybe through his brother, who is much friendlier. Just as I’ve been taught, I intend to civilize and educate the children for their own good.”

“Willow, my dear child, I just know you are going to make me proud of you; meeting this challenge.”

“When do I start?”

He drew up before the small house. “Tomorrow, my dear; maybe one of their own can do something to cool all this tension that’s been building lately.”

Willow smiled to herself. She liked children and looked forward to teaching them. Bear wouldn’t like that. Willow didn’t want to admit even to herself that she looked forward to besting that arrogant warrior who had glared at her so disdainfully!

Old Reverend Harlow lived alone since his wife had died, with only a part-time Indian housekeeper coming in. As he said, now that Willow had come to stay, she could keep up the house when she wasn’t teaching the Nez Perce children and save him paying that housekeeper’s salary. Of course, just because he and his wife had scrimped, saved, and prayed to get Willow a fine education, he wouldn’t want the girl to feel obligated.

Willow stayed up very late studying. She must be able to speak her language fluently and to translate English words for the children if she was to succeed. The next morning, Willow washed and dressed, putting on a pale green cotton calico over a corset, corset cover, three petticoats, long dark stockings, and pantalets. She combed her shiny black hair up in a demure bun on the back of her neck and went down to cook breakfast. At Miss Priddy’s school, Willow had worked in the kitchen and laundry to pay part of her tuition.

Reverend Harlow coughed, but nodded his approval as he came into the kitchen, taking a deep breath of the scent of frying bacon and coffee.

“Taz meimi,” she greeted him brightly, deciding she might as well practice her Nez Perce language skills. Her hard work had paid off; she could converse in either language.

“Good morning,” he returned her greeting, but his tone sounded grumpy. “My dear, you look just like any civilized schoolteacher on the frontier. If you didn’t tell anyone, they might not know you were Injun at all.”

He had evidently meant that as a compliment and Willow nodded, but inside, she felt stung. “Funny, but that’s just what they told me at school. In fact, Miss Priddy discouraged me from telling anyone; she said I might as well let well enough alone and besides, if I didn’t tell, I might make a good marriage.”

“I’ve even given that some thought.” He beamed at her as he sat down at the table and motioned her to sit. Then he bowed his head and in a sonorous voice intoned, “Dear Lord, we give thanks for this food and this teacher who has come to save the savages from themselves. May she civilize them as I have tried to do and failed. Amen. Pass the jelly.” He picked up a biscuit.

Willow got up to get the coffeepot, feeling a bit annoyed. She really didn’t remember much about the Harlows except what she had been told that because of them, she had been rescued from a drunken mother who had later died. Reverend Harlow sounded like a sanctimonious prig. “Perhaps you are expecting too much of me,” she said, as she poured coffee, “I’m just going to teach the children to read and write.”

“Well, it’s a start.” The old man gobbled the biscuit. “The sooner we get all these Indians to forget their heathen ways, behave like whites, talk like whites, the sooner all these cultural problems will be solved.”

Willow tried to remember how much she owed him. “I suppose you’re right.”

“It’s God’s will,” he assured her as he wiped butter from his wrinkled lips. “As a missionary, for my entire career, I’ve been assigned all over the West, beginning with Arkansas. If it wasn’t God’s will to subjugate the savages, why would I be here?”

It seemed so perfectly logical to him that Willow was taken aback as she sipped her coffee. “You don’t really like Indians, do you?”

“I am attempting to save their souls and they are too primitive to appreciate my efforts as were most of the others at the posts to which I’ve been assigned.”

“But you don’t really like them,” she said again, surprised at her own boldness.

He glared at her over the tops of his bifocals and reached for his handkerchief as he coughed again. “I hope you haven’t been mixing with those female suffragists,” he said, “I don’t think God approves of them at all; just like the savages. After what happened only last summer to the gallant General Custer up at the Little Big Horn, we probably should wipe out all Indians, but that doesn’t keep me from praying for their worthless souls and hoping to civilize them.”

She knew she shouldn’t, but Willow couldn’t seem to help herself. “Don’t you see a conflict in what you just said?”

He put down his cup with a clatter and glared at her. “A rebellious spirit is an abomination to the Lord, Willow. I think we need to pray about this and your task here in general.”

Perhaps he was right. Willow bent her head and tried to think humble thoughts while Reverend Harlow bowed his head and began beseeching God to teach the errant Willow humility and also to help save the souls of the redskin devils whose obstinacy and savagery were creating economic havoc in the Northwest by not bending to the white man’s superior will that was surely as God had planned it.

“Amen!” He cleared his throat and returned to his bacon and biscuits in a manner that belied his scrawny frame. “Do you remember any of your native language at all?”

“Some, and I’ve been studying, so it’s coming back to me,” Willow admitted, staring at her plate so she wouldn’t glare at the old man. “I speak enough so that I feel the children will be able to understand me.”

He grunted. “Better you should make all the little savages learn English.”

“I intend to do that, too, but, sir, if I can’t communicate with them, how can I teach them anything?”

“Quite so; quite so.” He lifted his cup with a feeble hand. “My dear child, you’ll have your work cut out for you with those nontreaty Nez Perce of Chief Joseph’s. The ones who have taken our religion have mostly signed the treaty, but those that belong to the Dreamers are backsliders who refuse to budge an inch; say they never signed that latest paper giving up their land.”

“Well, did they?” Willow peered at him over her cup.

“What difference does it make?” His voice rose. “Somebody signed it, that’s all that matters and now they have to get off the land. The army will enforce that, but I think Chief Joseph is a reasonable man; he won’t want to get his people killed.”

“I would think, as a missionary, you would be preaching about ‘blessed are the peacemakers.’ ”

He looked at her a long moment, blinked rheumy eyes as if trying to decide if she were being sarcastic, - seemed to decide that as a woman, she couldn’t possibly be that smart. “The whites are trying to keep the peace; but we may have to use the sword if those ignorant Indians won’t obey.”

“Just how big is the new reservation?”

The reverend shrugged. “About one-tenth the size they’ve got now, I think.”

“One-tenth?”

“It’s not as if they are using any of it except to roam around on.” He looked defensive. “If they aren’t going to farm it, why do they want it?”

“Well, maybe because it’s theirs,” Willow said.

“You indeed have a rebellious spirit,” the minister said, “that is bad in a woman. You remind me of my niece, Summer; except she was blond.”

“The girls at Miss Priddy’s still talk about her,” Willow said, “but no one knows much.”

The old man sighed. “Rebellious, Summer was. She was being sent to stay with me while I

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...