- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

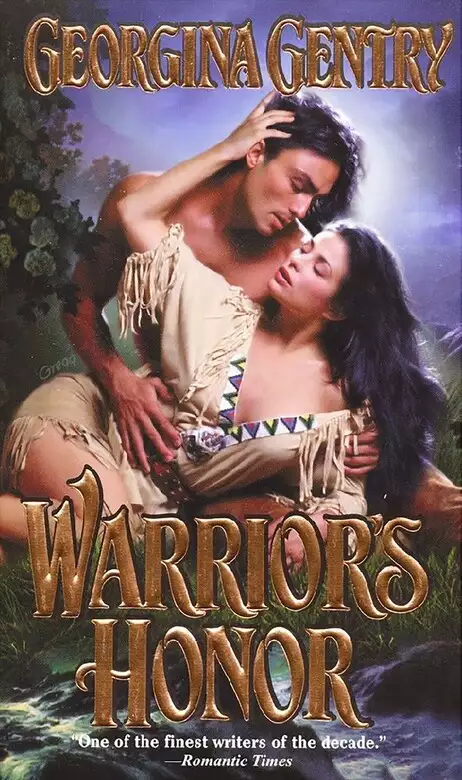

TORN BETWEEN LOVE AND DUTY A warrior who values duty above all else, Talako is honor bound to recapture a runaway brave sentenced to hang for his crimes. But then he confronts the fury and determination of ebony-haired Lusa, his quarry's sister. Forced to make Lusa his captive on a perilous trek through the wilderness, he cannot deny the desire to forget his quest and lose himself in the pleasures of her lush beauty. TRAPPED BY PASSION AND DESIRE Convinced Talako is hunting an innocent man, for Lusa all that matters is saving her brother, and she'll do it any way she can. Boldly, she dares to seduce her enemy with all the passionate fire raging through her blood. The last thing she expects is her own impossible need to surrender to the exquisite torment he ignites. . . and to a love that could bind her heart to his forever.

Release date: May 16, 2014

Publisher: Zebra Books

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Warrior's Honor

Georgina Gentry

Lusa stood on the sidelines with the cheering crowd, watching the game. No, that wasn’t true, she thought, trying not to blush. She was pretending to watch her brother play, but her gaze was on the unfamiliar warrior in the buckskin shirt.

Her father nudged her. “Good game! Your brother plays well today!”

“What? Oh, yes,” she said, but she didn’t look toward Chula. His name meant fox, and he was quick and smart like his namesake. “Father, who is that new man who wears a leather shirt in this heat? He must be loco.” Her own blue calico dress clung to her skin.

“What? Oh, that is John Talako. Best player I’ve seen in a long time,” Will Koi Chito answered. “Remember, I told you before you went off to school that my old friend, Wolf’s son, was coming to the Indian Territory?”

Lusa murmured, barely remembering that. If old Koi Chito had told her the man would be so tall and handsome, she might have paid more attention. Talako. It meant Gray Eagle in the Choctaw language. The name suited him, she decided.

Talako paused on the field to watch the girl, aware she was staring at him. So this was old Koi Chito’s mixed-blood daughter, Lusa, who had briefly been away at school back East. Her name meant black in their language, and her hair was dark as a crow’s wing. Except that her skin was a shade lighter and she wore a white girl’s blue calico dress, she didn’t look as if her mother had been half white.

“Look out, Talako!” the team leader shouted.

Lusa put her hand over her lips to hold back a scream of warning as she saw Chula send the hard leather ball flying toward Talako. It caught him in the face and he staggered and slumped to the ground.

“Come!” her father said, and they ran onto the field.

Around them, the crowd was muttering. “Chula hit it toward him on purpose! He meant to hit him!”

“I did not!” her brother shouted. “It was an accident!”

“Of course it was!” Lusa defended her younger half-brother loyally as she followed her father over to the crowd gathering around the fallen man. Chula wouldn’t deliberately try to injure the other team’s best player.

The crowd made way for the old lighthorseman and his daughter as Koi Chito limped toward the injured man and put one frail hand on the man’s broad shoulder as Talako pulled himself into a sitting position.

“Talako, are you all right?”

“I—I think so.” He wiped blood from his mouth with the back of one big hand. His voice carried the slow drawl of the deep South.

“Chula hit him on purpose!” shouted one of the players.

“I did not!” her handsome younger brother again denied hotly. “He wasn’t paying attention, or he would have fielded that ball.”

That was true, Lusa thought. She had been keenly aware Talako was watching her as the ball flew through the air. Now the injured warrior wiped blood from his cut lip. He gave Chula a long look, then glanced from Koi Chito to Lusa. “Perhaps it was my fault,” he said finally. “I let my attention be diverted.”

The way he was looking at her brought a hot flush to Lusa’s skin. Innocent though she was, she knew desire when she saw it in a man’s eyes. And yet there was something else there, too—disdain and distrust. Was it something about her personally, or did he have bad feelings for all women?

“Let us get on with the game!” commanded the team leader. “Talako, do you want to play or do you want to sit out the rest of the game?”

Talako shook his head. “I will play.” He staggered to his feet, shaking his head as if to clear it.

Lusa blurted, “You don’t look well enough to play.”

He paused, an expression of scorn on his chiseled features. “I don’t need advice from a woman.”

“I merely thought—” Lusa began.

“Well, don’t,” Talako snapped. He walked a little unsteadily back to the field.

Lusa turned toward her father with an indignant flounce of her petticoats. “What a rude, hostile—”

“Stop it.” Father shook his white head and took her arm, leading her back to the sidelines. “I’m afraid Talako has a poor opinion of women.”

“Well, now I’ve got a poor opinion of him,” Lusa fumed.

“Clear the field!” the team leaders yelled.

The spectators returned to the sidelines and the stickball game resumed. Choctaw stickball was a rough, fast game, and the agile warriors delighted in it, swinging their sticks and hitting the leather ball hard, driving it toward their goals at each end of the field.

“My old friend Nashoba and I had always hoped for a marriage between our two families, but after the other son’s tragedy ...”

Lusa waited for Father to continue, but the old warrior had decided he’d said enough.

“So he has no woman?” Lusa’s curiosity was piqued as

she watched Talako slam the ball hard, sending it smashing across the field. “I don’t wonder. He’s too rude and brusque for any woman, even an old-fashioned one.”

Koi Chito shook his head. “He’s already made it clear he’s not interested. I approached him while you were away back East.”

“You offered me in marriage without telling me?” Lusa seethed with rage and humiliation. She wasn’t sure whether she was more annoyed with her very traditional father for trying to set up her marriage or with Talako for turning it down.

“Does it matter,” the old man asked, “since he wasn’t interested?”

Wasn’t interested! Men had always been attracted to her beauty, but Lusa wanted more out of life than being an old-fashioned Choctaw wife. When her tribe forgot its useless traditions and took the white man’s path, they would all be better off.

She tried to concentrate on the playing field, but she was too keenly aware of the big, virile Choctaw, and seething inside at the rejection. “Father, marriage is the last thing on my mind. I’m going to go back to the white school if I can find a way.”

“You can forget that dream, daughter,” her father reminded her as the game resumed. “Now that the rich white man has withdrawn your scholarship, perhaps you can get a position teaching at the Wheelock mission school. You have enough education for that.”

Disappointed, Lusa didn’t answer. She must not argue with her father. It was not the Choctaw way. To keep her mind off her problem, she tried to concentrate on the action and cheered on her brother’s team. The opposing team was lagging now, certainly because their best player, Talako, was slowing. Perhaps he was hurt more than he was willing to admit. In the end, her brother’s team won, and it had been an important game.

The teams and the crowds began to leave the field. Chula swaggered over to them, his handsome face lit with pride. “Did you see? We won!”

Talako hesitated, then limped over, nodded to Koi Chito, and held out his hand to Chula. “Congratulations.” Then he turned and started to leave.

Koi Chito called to him. “Talako, don’t leave so soon.”

The tall, virile Choctaw turned back toward them, his buckskin skin shirt dark with sweat. “I have to put some cold water on my face.” He frowned at the gleeful young man dancing about and crowing with triumph.

“You’re being a poor sport, Talako!” Lusa blurted. “Chula’s team won fair and square.”

“Lusa!” Koi Chito shouted. “It is not proper to scold a warrior.”

Now Talako hesitated, smiling ever so slightly, but his dark eyes were cold and hostile as they swept over her. “Your daughter does not strike me as too worried about what is proper for a Choctaw girl.”

Lusa’s cheeks burned at the implied insult. “Maybe that is because my mother was half white!”

“All women are the same, white or brown.” A slight sneer curved his swollen, cut lip.

“Talako,” Chula said, “I truly did not mean to hit you.”

The older man gave her brother a steely look but said nothing. It was evident he did not believe Chula. That really annoyed Lusa. She and her father had always doted on and spoiled her half brother, but he was just an immature boy, after all.

“Accept our family’s apologies for your injury,” her father put in hurriedly. “I’m sure my son did not deliberately aim for your face.”

“Of course not!” Chula said.

The big Choctaw took a deep breath and put his hand on the old man’s shoulder. “I do not forget, Koi Chito, that you and my father were close friends many years ago before you left Mississippi and that your brother died alongside old Wolf last year.”

The other nodded. “Sad memory. Please overlook my daughter, Lusa. She’s been away at the white man’s school and has little use for our traditions.”

“Like the whites,” Talako said coldly, “she is lacking in manners.”

“And like the Choctaw, you are a slave to tradition,” Lusa snapped back.

“Lusa!” said her father, running one hand through his mane of white hair in helpless frustration. He did look like his namesake the lion, she thought.

Talako looked her up and down slowly, as if he might be reconsidering. Desire shone in his dark eyes. “You weren’t gone very long.”

The way he was looking her over made her cross her arms defensively across her breasts. “I was at Miss Priddy’s Academy on a scholarship,” Lusa explained, “but when Summer Van Schuyler got expelled for leading a woman’s rights protest, her father cancelled my tuition.”

Chula laughed. “Yes, she was back within weeks—and here I was hoping she’d meet some rich white man who’d marry her and we’d be living a life of ease.”

Talako didn’t smile. “I’m not sure a white man could deal with a girl like this one. She’s spirited.”

She couldn’t decide if that was disapproval or admiration in his tone, but she was angry at his arrogance. “I’m not sure any man could, and I don’t intend to find out!”

“Lusa,” snapped her father, “you will not speak to a member of the lighthorsemen in that tone. It is not seemly for a maiden.”

She started to say more, but thought better of it. She would not embarrass her elderly father publicly because of this arrogant newcomer who, because he was angry with her brother, seemed to be baiting her.

Some of the other ballplayers joined them now, Chula’s teammates happy and laughing over their triumph. Immediately, she felt the tension lessen.

An elderly couple joined them, old Tom Halonlabi, Bullfrog, and his plump wife. “Good game,” Bullfrog said, “But Chula, you need to be careful. You wouldn’t want anyone to think you deliberately aimed for Talako’s face. It isn’t honorable.”

“He didn’t!” Lusa defended him hotly. “Why does everyone blame my brother?”

Her father looked embarrassed and uncertain. “I must apologize for my daughter. I’m afraid she is alla tek haksi.”

Rude girl. Lusa gritted her teeth.

“No need,” said old Bullfrog. “Come, I will buy everyone some refreshments.”

The crowd around them cheered, but Koi Chito said, “That’s a very generous offer, Halonlabi, but the cost—”

“Nonsense!” The old man chortled and pulled a small, red beaded bag from his shirt. He held it up triumphantly. “I sold some cattle yesterday. I’ve got plenty of money, paid me in twenty-dollar gold pieces.” He jingled the bag as if to prove it.

“Old fool,” his wife grumbled. “He’s told everyone about the sale. He’s that proud.”

Talako ran his finger gingerly over his swollen, discolored face. “Yakoke,” he thanked them in the Choctaw language. “But I’d better go see to my lip. It’s swelling.”

The old woman looked Talako over curiously. “And who is this newcomer?”

“Oh,” Koi Chito said, “you haven’t met Talako. He just arrived a few weeks ago from our old country. He’s old Wolf’s son and a lighthorseman.”

Immediately both elderly wrinkled brown faces lit up with smiles.

The old man put the red beaded sack in his pocket and offered his hand. “I knew your father in the old days, a very honorable man. I hope he’s well.”

Talako shook his hand. “My father is dead these six months, murdered along with Koi Chito’s brother.”

Father had not spoken much of this. She saw Talako’s dark eyes soften with grief and felt an immediate pang at having clashed with the stranger only moments before.

Old Bullfrog nodded. “Oh, yes, I heard about that cowardly deed. I had forgotten.”

She saw the two old men exchange glances, as if there were something else they could not discuss.

Chula must not have been listening to the conversation, because he broke in restlessly, “Father, may I go now? My friends and I want to celebrate our victory.”

Koi Chito smiled at his beloved son and dismissed him with a wave. “Go on and have a good time. Don’t get into any trouble.”

Chula laughed. “Now, Father, you know I would never do anything to blacken our honor.” He turned and hurried to join his friends. They walked toward the general store, laughing and boasting as they left.

“Fine boy,” old Bullfrog said. “He’ll be a credit to his family.”

Koi Chito nodded modestly. “My only son. I fear I dote on him too much.”

“We both spoil him a little,” Lusa conceded, “but he’s so charming we can’t help it.” She had never found it in her to resent the fact her father loved Chula so much more than he loved her. She watched Chula go, her heart full of love and pride. Lusa’s half-breed mother had died of cholera and old Koi Chito had married a Choctaw girl, Chula’s mother—but she was long dead, too, and Lusa was the only mother the boy had ever known.

Old Bullfrog jingled the bag of gold in his shirt. “I only wish I had had such a fine son, but ours died on the Trail of Tears long ago.”

The old woman’s dark eyes clouded up and she twisted the wide gold wedding band on her plump finger, but her hands were shaking.

Lusa’s heart went out to them. “It was a terrible thing for all five tribes.”

The silent Talako touched his face again. “I must be going.”

The gentle old woman turned her attention back to him. “Where are you staying? With Koi Chito?”

“I invited him,” Koi Chito said.

Talako shook his head. “I appreciated the offer, but Koi Chito’s house is small and I would crowd them too much. I’m staying in a rented room behind the general store.”

“Ah, no.” The old woman clicked her tongue in disapproval. “We have a large ranch and no children. You should come stay with us.”

“Oh, I couldn’t put you out,” Talako protested.

“Nonsense!” the old man said. “We have plenty of room. Come out tomorrow and see for yourself.”

“Besides,” the woman said, “with the old fool telling everyone within a hundred miles how much money he got for those cattle, I’d sleep better at night knowing a lighthorseman was staying at the house. Are you a good shot?”

“Some say so,” Talako answered modestly. Lusa wondered about the sadness mirrored suddenly in his dark eyes.

“Good!” The old woman nodded as if it were settled. “You come out tomorrow to see our place and I’ll fix good food, old-fashioned Choctaw cooking. You like tanchi ashela honi?”

“Baked corn pudding?” Talako smiled. “Served up with boiled poke greens? My favorite!”

The old woman beamed at him.

“And I’ll show you my fine cattle,” the old man said, “Koi Chito can tell you how to get there.”

“Yakoke,” Talako thanked them.

“Speaking of dinner,” Koi Chito said, “Talako, now that Lusa’s back, you should come to dinner at our ranch sometime. Lusa is a very good cook, too.”

There was a moment of silence. Lusa knew her father was waiting for her to second his invitation, to urge the other man to come, but she was still angry with Talako for his snide insults to her as well as his hints that her beloved Chula might have hit him deliberately.

“I’m sure Talako is much too busy to come to dinner, Father.”

Talako only looked at her, a slight smile on his face as if he could not believe she was not being hospitable, as the Choctaw traditionally were.

The old woman cleared her throat in the awkward silence. “I thought we were all going to the store for a drink.”

“Thank you, but no,” Talako said. “I need to get some cold water on my face before it swells any more.” He nodded to the group and strode away.

“We must be going, too.” Lusa nodded to the old couple, then turned with a swirl of petticoats and headed for the family buggy.

“Lusa!” She heard her father’s voice thunder behind her and knew she was about to face a stern lecture, but she didn’t care. She wasn’t about to spend hours over a hot stove for a man who annoyed her as much as Talako did. The thought rankled that Father had offered her in marriage and this tall, hostile warrior hadn’t wanted her.

Father joined her in the buggy and drove away with a snap of his little whip. “You shame me, Lusa.”

She glanced back over her shoulder and watched Talako disappear around the corner of the general store toward his room.

“I’m sorry, Father, but you know what he thought about our dear Chula.”

“Well, of course he’s wrong. Anyway, Talako would make a wonderful addition to our family.”

That subject again, she thought with annoyance. No doubt Father thought she should use her charm and cooking to change the big man’s mind. “He’s too old-fashioned for me. Much too traditional.”

“That is not a bad thing,” Koi Chito noted as he drove. “I believe in the old ways of the Choctaw.”

“We will all be better off when we forget all that rubbish about honor and tradition and begin to follow the white man’s road completely.”

“Nevertheless, the next time you see John Talako, I expect you to treat him with respect. He’s a legendary lighthorseman in Mississippi,” Father said.

“Then why didn’t he stay in Mississippi?” Lusa retorted.

“After everything that had happened, maybe he couldn’t bear it. He carries some heavy burdens.”

“Yes, I remember now that you said his father was murdered along with your brother.” Her heart went out to Talako in spite of his brusque manner.

“And there were other things ... never mind,” Father said. “Captain Raven was pleased to have him join our local lighthorse group. The captain says things are much more lawless here than they were in Mississippi. He says with all the renegades and white outlaws coming into the Choctaw Nation, we need the best men we can get.”

Her curiosity was aroused. Old Koi Chito was a retired lighthorseman himself, that elite Choctaw law enforcement unit that kept order among the tribe. They had a reputation for being expert shots and relentless trackers. “He doesn’t seem to have a very high opinion of women.”

Father shrugged and stared straight ahead as the bay horse clopped along the dusty road. “It’s his past. His unfaithful mother and—never mind the rest of it.”

“But yet,” Lusa thought aloud, “he couldn’t take his eyes off me. That’s why he got hit in the mouth.”

Immediately, Father’s weathered face grew troubled. “I wish I could be sure your brother didn’t do that deliberately.”

“Father! How could you even suspect such a thing?” Lusa was horrified. “Chula may be a bit spoiled, but his own honor and our family’s is as important to him as it is to you. If that big brute Talako had been watching the ball instead of staring at me—”

“Are you sure he was looking at you?” Father grinned. “Perhaps you imagined that.”

“He was watching me,” she insisted.

“It’s a good sign,” Koi Chito said under his breath, “but until he resolves the demons of his past, he’ll not want to marry you or any other.”

“Please forget that!” She was more than a little annoyed. “I expect to go back East and marry a white man who can appreciate me.”

Father only sighed and snapped the reins so the old bay horse broke into a trot. “Let’s get home. I seem to tire so easily these days.”

She had forgotten how old her father was. Lusa glanced sideways at him. Koi Chito. It meant lion, and he looked like an old lion, dignified, with a mane of silver hair. She certainly couldn’t run the ranch without him if Chula didn’t begin to show more interest in the place. Of course, her handsome, charming brother was immature for seventeen.

Now John Talako, there was a man who seemed willing and able to take responsibility on those wide shoulders. Gray Eagle. Yes, it suited him. He must be in his mid twenties, maybe closer to thirty. Or was it only because his eyes seemed so tragic and old, as if he’d already seen too much?

The next morning, Lusa checked the pantry and decided she needed to drive into town for supplies. Old Koi Chito sat at the kitchen table drinking the coffee she had made. “Would you care to go, Father?”

“No.” He shook his head. “It’s a long trip and I don’t sleep well anymore. I thought something awakened me in the middle of the night, then decided it was my imagination.”

Lusa froze, wondering what time her little brother had finally come in.

“Besides”—Koi Chito frowned at her—“I might run into Talako, and I was embarrassed by your rude behavior toward him yesterday.”

Would she never hear the end of that? “No more than he was to me.”

“Since he arrived here a few weeks ago,” Koi Chito said wryly, “Talako has been a good friend to me, as was his father in the old days in Mississippi. He did me and your brother a favor just last week.”

“Oh?” She waited curiously, but Koi Chito merely sipped his coffee and said nothing, seemingly lost in thought.

She began to gather her things for the trip to town.

“It’s past sunrise,” Father frowned. “Is your brother up yet?”

“Uh, no,” Lusa said. “Remember, he and his friends were celebrating their win. He probably came in late, I’m afraid.”

Koi Chito frowned. “Chula likes Choc beer too much, and some of those boys he hangs around with are no good.”

“Don’t be so hard on him,” Lusa pleaded. “Because he’s your only son, maybe you expect too much.”

“Because he’s my only son, perhaps I spoil him too much,” Father frowned. “Chula is seventeen, and when I measure him against Talako—”

“Talako! Talako!” She was beginning to dislike the name. “That’s not fair. Chula’s just a boy, high-spirited and maybe a little irresponsible, but very sweet, without a mean bone in his body. Just you wait. Chula will grow up and be a fine man, not hard-edged like that lawman.”

The other frowned and shook his mane of silver hair. “When I was seventeen, I was looking after my parents, taking on a man’s responsibilities. I’m getting old, Lusa. I can’t run this ranch by myself much longer, and yet I doubt Chula’s ability to take over.”

“You worry too much,” Lusa scolded. “I’m sure things will turn out just fine. Now you go out and harness the horse so I can go to town.”

Koi Chito got up and went over to peer out the window. “Looks like it’s going to rain.”

“Good, we could use it.” Lusa busied herself with her list. “It’s dry as a bone for miles around. If it turns stormy, I’ll stay at the store until it clears off.”

“If it’s very late, you might get Talako to escort you back,” Koi Chito suggested. “All sorts of white outlaws and mixed-blood renegades have been coming into the Choctaw Nation.”

Lusa gritted her teeth. She could not get the stubborn old man’s mind off Talako. “If I run into your old friend’s son, I’ll make amends for yesterday by inviting him to dinner.”

Her father’s weathered brown face beamed. “That would be good.” He started out the back door. “I’ll hitch up the buggy for you. Then I’m going out to the south pasture to fix that fence the cattle tore down.”

“Don’t disturb Chula yet,” Lusa called after him. “If he’s been into Choc beer, he’ll feel terrible.”

Her father frowned and nodded as he headed out the door. Lusa watched him go, then ran to Chula’s bedroom. With a sigh of relief, she saw he was in bed asleep. His bed had been empty when she had checked in the middle of the night. Now the boy snored, and he reeked of the locally brewed beer.

Wrinkling her nose at the scent, she tiptoed to the window and closed it. Thank goodness Chula’d had the good sense to come through the window instead of down the hall past Father’s room.

Lusa leaned over and picked up his scattered clothing, putting his things in a neat pile. Chula snored on.

She sighed, wondering if she should stop protecting her happy-go-lucky brother from her father’s stern, old-fashioned discipline. It seemed she had made excuses for and looked after her little brother all her life. After all, he’d been deprived of a mother and should be judged a little more leniently.

Chula was so charming, everyone seemed willing to overlook his rowdiness and mischievousness. Several times in the last year, Chula had gone out, caroused all night with his friends, and crawled back through his window without Father ever knowing he was gone. This time, there would be a row between the old man and Chula that she would have to referee. She must have a stern talk with her little brother about mending his ways.

But not now. She smiled, looking down at him. There was a slight smile on his handsome dark face. He seemed like a cross between a cherub and a mischievous little boy. Lusa stroked his black hair away from his forehead, sighed, and left his room, carefully closing the door behind her. Didn’t Chula and his friends deserve a little innocent fun? After all, they had won the game.

That made her think of Talako again, and she frowned in annoyance as she got her list and a scarf in case it rained. She heard Father bring the buggy around front and she went out onto the rambling porch. “Chula’s not up yet. I’ve left some biscuits and fried pork chops on the stove for him.”

“He ought to be out working in the fields,” Father grumbled.

“Well, let him have his fun,” Lusa said. “It’s hard to be raised without a mother.”

Her father’s face saddened. “As you both were. Life has been hard for the Choctaw ever since the treaty at Dancing Rabbit Creek. Our chiefs were fools to sign it. But then, they were fools to trust. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...