- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

In this thrilling sequel to Seventh Son, Alvin Maker is awakening to many mysteries: his own strange powers, the magic of the American frontier, and the special virtues of its chosen people, the Native Americans.

Alvin has discovered his own unique talent for making things whole again. Now he summons all his powers to prevent the tragic war between Native Americans and the white settlers of North America.

Don't miss the first Alvin Maker book, Seventh Son.

A Blackstone Audio production.

Release date: November 30, 2009

Publisher: Tom Doherty Associates

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

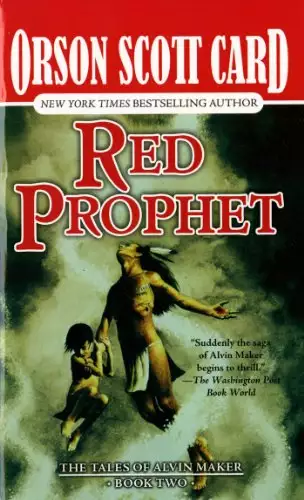

Red Prophet

Orson Scott Card

Not many flatboats were getting down the Hio these days, not with pioneers aboard, anyway, not with families and tools and furniture and seed and a few shoats to start a pig herd. It took only a couple of fire arrows and pretty soon some tribe of Reds would have themselves a string of half-charred scalps to sell to the French in Detroit.

But Hooch Palmer had no such trouble. The Reds all knew the look of his flatboat, stacked high with kegs. Most of those kegs sloshed with whisky, which was about the only musical sound them Reds understood. But in the middle of the vast heap of cooperage there was one keg that didn't slosh. It was filled with gunpowder, and it had a fuse attached.

How did he use that gunpowder? They'd be floating along with the current, poling on round a bend, and all of a sudden there'd be a half-dozen canoes filled with painted-up Reds of the Kicky-Poo persuasion. Or they'd see a fire burning near shore, and some Shaw-Nee devils dancing around with arrows ready to set alight.

For most folks that meant it was time to pray, fight, and die. Not Hooch, though. He'd stand right up in the middle of that flatboat, a torch in one hand and the fuse in the other, and shout, "Blow up whisky! Blow up whisky!"

Well, most Reds didn't talk much English, but they sure knew what "blow up" and "whisky" meant. And instead of arrows flying or canoes overtaking them, pretty soon them canoes passed by him on the far side of the river. Some Red yelled, "Carthage City!" and Hooch hollered back, "That's right!" and the canoes just zipped on down the Hio, heading for where that likker would soon be sold.

The poleboys, of course, it was their first trip downriver, and they didn't know all that Hooch Palmer knew, so they about filled their trousers first time they saw them Reds with fire arrows. And when they saw Hooch holding his torch by that fuse, they like to jumped right in the river. Hooch just laughed and laughed. "You boys don't know about Reds and likker," he said. "They won't do nothing that might cause a single drop from these kegs to spill into the Hio. They'd kill their own mother and not think twice, if she stood between them and a keg, but they won't touch us as long as I got the gunpowder ready to blow if they lay one hand on me."

Privately the poleboys might wonder if Hooch really would blow the whole raft, crew and all, but the fact is Hooch would. He wasn't much of a thinker, nor did he spend much time brooding about death and the hereafter or such philosophical questions, but this much he had decided: when he died, he supposed he wouldn't die alone. He also supposed that if somebody killed him, they'd get no profit from the deed, none at all. Specially not some half-drunk weak-sister cowardly Red with a scalping knife.

The best secret of all was, Hooch wouldn't need no torch and he wouldn't need no fuse, neither. Why, that fuse didn't even go right into the gunpowder keg, if the truth be known--Hooch didn't want a chance of that powder going off by accident. No, if Hooch ever needed to blow up his flatboat, he could just set down and think about it for a while. And pretty soon that powder would start to hotten up right smart, and maybe a little smoke would come off it, and then pow! it goes off.

That's right. Old Hooch was a spark. Oh, there's some folks says there's no such thing as a spark, and for proof they say, "Have you ever met a spark, or knowed anybody who did?" but that's no proof at all. Cause if you happen to be a spark, you don't go around telling everybody, do you? It's not as if anybody's hoping to hire your services--it's too easy to use flint and steel, or even them alchemical matches. No, the only value there is to being a spark is if you want to start a fire from a distance, and the only time you want to do that is if it's a bad fire, meant to hurt somebody, burn down a building, blow something up. And if you hire out that kind of service, you don't exactly put up a sign that says Spark For Hire.

Worst of it is that if word once gets around that you're a spark, every little fife gets blamed on you. Somebody's boy lights up a pipe out in the barn, and the barn burns down--does that boy ever say, "Yep, Pa, it was me all right." No sir, that boy says, "Must've been some spark set that fire, Pa!" and then they go looking for you, the neighborhood scapegoat. No, Hooch was no fool. He didn't ever tell nobody about how he could get things het up and flaming.

There was another reason Hooch didn't use his sparking ability too much. It was a reason so secret that Hooch didn't rightly know it himself. Thing was, fire scared him. Scared him deep. The way some folks is scared of water, and so they go to sea; and some folks is scared of death, and so they take up gravedigging; and some folks is scared of God, and so they set to preaching. Well Hooch feared the fire like he feared no other thing, and so he was always drawn to it, with that sick feeling in his stomach; but when it was time for him to lay a fire himself, why, he'd back off, he'd delay, he'd think of reasons why he shouldn't do it at all. Hooch had a knack, but he was powerful reluctant to make much use of it.

But he would have done it. He would have blown up that powder and himself and his poleboys and all his likker, before he'd let a Red take it by murder. Hooch might have his bad fear of fire, but he'd overcome it right quick if he got mad enough.

Good thing, then, that the Reds loved likker so much they didn't want to risk spilling a drop. No canoe came too close, no arrow whizzed in to thud and twang against a keg, and Hooch and his kegs and casks and firkins and barrels all slipped along the top of the water peaceful as you please, clear to Carthage City, which was Governor Harrison's high-falutin name for a stockade with a hundred soldiers right smack where the Little My-Ammy River met the Hio. But Bill Harrison was the kind of man who gave the name first, then worked hard to make the place live up to the name. And sure enough, there was about fifty chimney fires outside the stockade this time, which meant Carthage City was almost up to being a village.

He could hear them yelling before he hove into view of the wharf--there must be Reds who spent half their life just setting on the riverbank waiting for the likker boat to come in. And Hooch knew they were specially eager this time, seeing as how some money changed hands back in Fort Dekane, so the other likker dealers got held up this way and that until old Carthage City must be dry as the inside of a bull's tit. Now here comes Hooch with his flat-boat loaded up heavier than they ever saw, and he'd get a price this time, that's for sure.

Bill Harrison might be vain as a partridge, taking on airs and calling himself governor when nobody elected him and nobody appointed him but his own self, but he knew his business. He had those boys of his in smart-looking uniforms, lined up at the wharf just as neat as you please, their muskets loaded and ready to shoot down the first Red who so much as took a step toward the shore. It was no formality, neither--them Reds looked mighty eager, Hooch could see. Not jumping up and down like children, of course, but just standing there, just standing and watching, right out in the open, not caring who saw them, half-naked the way they mostly were in summertime. Standing there all humble, all ready to bow and scrape, to beg and plead, to say, Please Mr. Hooch one keg for thirty deerskins, oh that would sound sweet, oh indeed it would; Please Mr. Hooch one tin cup of likker for these ten muskrat hides. "Whee-haw!" cried Hooch. The poleboys looked at him like he was crazy, cause they didn't know, they never saw how these Reds used to look, back before Governor Harrison set up shop here, the way they never deigned to look at a White man, the way you had to crawl into their wicky-ups and choke half to death on smoke and steam and sit there making signs and talking their jub-jub until you got permission to trade. Used to be the Reds would be standing there with bows and spears, and you'd be scared to death they'd decide your scalp was worth more than your trade goods.

Not anymore. Now they didn't have a single weapon among them. Now their tongues just hung out waiting for likker. And they'd drink and drink and drink and drink and drink and whee-haw! They'd drop down dead before they'd ever stop drinking, which was the best thing of all, best thing of all. Only good Red's a dead Red, Hooch always said, and the way he and Bill Harrison had things going now, they had them Reds dying of likker at a good clip, and paying for the privilege along the way.

So Hooch was about as happy a man as you ever saw when they tied up at the Carthage City Wharf. The sergeant even saluted him, if you could believe it! A far cry from the way the U.S. Marshalls treated him back in Suskwahenny, acting like he was scum they just scraped off the privy seat. Out here in this new country, free-spirited men like Hooch were treated most like gentlemen, and that suited Hooch just fine. Let them pioneers with their tough ugly wives and wiry little brats go hack down trees and cut up the dirt and raise corn and hogs just to live. Not Hooch. He'd come in after, after the fields were all nice and neat looking and the houses were all in fine rows on squared-off streets, and then he'd take his money and buy him the biggest house in town, and the banker would step off the sidewalk into the mud to make way for him, and the mayor would call him sir--if he didn't decide to be mayor himself by then.

This was the message of the sergeant's salute, telling his future for him, when he stepped ashore.

"We'll unload here, Mr. Hooch," said the sergeant.

"I've got a bill of lading," said Hooch, "so let's have no privateering by your boys. Though I'd allow as how there's probably one keg of good rye whisky that somehow didn't exactly get counted on here. I'd bet that one keg wouldn't be missed."

"We'll be as careful as you please, sir," said the sergeant, but he had a grin so wide it showed his hind teeth, and Hooch knew he'd find a way to keep a good half of that extra keg for himself. If he was stupid, he'd sell his half-keg bit by bit to the Reds. You don't get rich off a half keg of whisky. No, if that sergeant was smart, he'd share that half keg, shot by shot, with the officers that seemed most likely to give him advancement, and if he kept that up, someday that sergeant wouldn't be out greeting flatboats, no sir, he'd be sitting in officers' quarters with a pretty wife in his bedroom and a good steel sword at his hip.

Not that Hooch would ever tell this to the sergeant. The way Hooch figured, if a man had to be told, he didn't have brains enough to do the job anyway. And if he had the brains to bring it off, he didn't need no flatboat likker dealer telling him what to do.

"Governor Harrison wants to see you," said the sergeant.

"And I want to see him," said Hooch. "But I need a bath and a shave and clean clothes first."

"Governor says for you to stay in the old mansion."

"Old one?" said Hooch. Harrison had built the official mansion only four years before. Hooch could think of only one reason why Bill might have upped and built another so soon. "Well, now, has Governor Bill gone and got hisself a new wife?"

"He has," said the sergeant. "Pretty as you please, and only fifteen years old, if you like that! She's from Manhattan, though, so she don't talk much English or anyway it don't sound like English when she does."

That was all right with Hooch. He talked Dutch real good, almost as good as he talked English and a lot better than he talked Shaw-Nee. He'd make friends with Bill Harrison's wife in no time. He even toyed with the idea of--but no, no, it wasn't no good to mess with another man's woman. Hooch had the desire often enough, but he knew things got way too complicated once you set foot on that road. Besides, he didn't really need no White woman, not with all these thirsty squaws around.

Would Bill Harrison bring his children out here, now he had a second wife? Hooch wasn't too sure how old them boys would be now, but old enough they might relish the frontier life. Still, Hooch had a vague feeling that the boys'd be a lot better off staying in Philadelphia with their aunt. Not because they shouldn't be out in wild country, but because they shouldn't be near their father. Hooch liked Bill Harrison just fine, but he wouldn't pick him as the ideal guardian for children--even for Bill's own.

Hooch stopped at the gate of the stockade. Now, there was a nice touch. Right along with the standard hexes and tokens that were supposed to ward off enemies and fire and other such things, Governor Bill had put up a sign, the width of the gate. In big letters it said

CARTHAGE CITY

and in smaller letters it said

CAPITAL OF THE STATE OF WOBBISH

which was just the sort of thing old Bill would think of. In a way, he expected that sign was more powerful than any of the hexes. As a spark, for instance, Hooch knew that the hex against fire wouldn't stop him, it'd just make it harder to start a fire up right near the hex. If he got a good blaze going somewhere else, that hex would burn up just like anything else. But that sign, naming Wobbish a state and Carthage its capital, why, that might actually have some power in it, power over the way folks thought. If you say a thing often enough, people come to expect it to be true, and pretty soon it becomes true. Oh, not something like "The moon is going to stop in its tracks and go backward tonight," cause for that to work the moon'd have to hear your words. But if you say things like "That girl's easy" or "That man's a thief," it doesn't much matter whether the person you're talking about believes you or not--everybody else comes to believe it, and treats them like it was true. So Hooch figured that if Harrison got enough people to see a sign that named Carthage as the capital of the state of Wobbish, someday it'd plumb come to be.

Fact is, though, Hooch didn't much care whether it was Harrison who got to be governor and put his capital in Carthage City, or whether it was that teetotaling self-righteous prig Armor-of-God Weaver up north, where Tippy-Canoe Creek flowed into the Wobbish River, who got to be governor and make Vigor Church the capital. Let those two fight it out; whoever won, Hooch intended to be a rich man and do as he liked. Either that or see the whole place go up in flames. If Hooch ever got completely beat down and broken, he'd make sure nobody else profited. When a spark had no hope left, he could still get even, which is about all the good Hooch figured he got out of being a spark.

Well, of course, as a spark he made sure his bathwater was always hot, so it wasn't a total loss. Sure was a nice change, getting off the river and back into civilized life. The clothes laid out for him were clean, and it felt good to get that prickly beard off his face. Not to mention the fact that the squaw who bathed him was real eager to get an extra dose of likker, and if Harrison hadn't sent a soldier knocking on his door telling him to hurry it up, Hooch might have collected the first installment of her trade goods. Instead, though, he dried and dressed.

She looked real concerned when he started for the door. "You be back?" she asked.

"Look here, of course I will," he said. "And I'll have a keg with me."

"Before dark though," she said.

"Well maybe yes and maybe no," he answered. "Who cares?"

"After dark, all Reds like me, outside fort."

"Is that so," murmured Hooch. "Well, I'll try to be back before dark. And if I don't, I'll remember you. May forget your face, but I won't forget your hands, hey? That was a real nice bath."

She smiled, but it was a grotesque imitation of a real smile. Hooch just couldn't figure out why the Reds didn't die out years ago, their women were so ugly. But if you kind of closed your eyes, a squaw would do well enough until you could get back to real women.

It wasn't just a new mansion Harrison had built--he had added a whole new section of stockade, so the fort was about twice the size it used to be. And a good solid parapet ran the whole length of the stockade. Harrison was ready for war. That made Hooch pretty uneasy. The likker trade didn't thrive too good in wartime. The kind of Reds who fought battles weren't the kind of Reds who drank likker. Hooch saw so much of the latter kind that he pretty much forgot the former kind existed. There was even a cannon. No, two cannons. This didn't look good at all.

Harrison's office wasn't in the mansion, though. It was in another building entirely, a new headquarters building, and Harrison's office was in the southwest corner, with lots of light. Hooch noticed that besides the normal complement of soldiers on guard and officers doing paperwork, there were several Reds sprawling or sitting in the headquarters building. Harrison's tame Reds, of course--he always kept a few around.

But there were more tame Reds than usual, and the only one Hooch recognized was Lolla-Wossiky, a one-eyed Shaw-Nee who was always about the drunkest Red who wasn't dead yet. Even the other Reds made fun of him, he was so bad, a real lickspittle.

What made it even funnier was the fact that Harrison himself was the man who shot Lolla-Wossiky's father, some fifteen years ago, when Lolla-Wossiky was just a little tyke, standing right there watching. Harrison even told the story sometimes right in front of Lolla-Wossiky, and the one-eyed drunk just nodded and laughed and grinned and acted like he had no brains at all, no human dignity, just about the lowest, crawliest Red that Hooch ever seen. He didn't even care about revenge for his dead papa, just so long as he got his likker. No, Hooch wasn't a bit surprised to see that Lolla-Wossiky was lying right on the floor outside Harrison's office, so every time the door opened, it bumped him right in the butt. Incredibly, even now, when there hadn't been new likker in Carthage City in four months, Lolla-Wossiky was pickled. He saw Hooch come in, sat up on one elbow, waved an arm in greeting, and then rocked back onto the floor without a sound. The handkerchief he kept tied over his missing eye was out of place, so the empty socket with the sucked-in eyelids was plainly visible. Hooch felt like that empty eye was looking at him. He didn't like that feeling. He didn't like Lolla-Wossiky. Harrison was the kind of man who liked having such squalid creatures around--made him feel real good about himself, by contrast, Hooch figured--but Hooch didn't like seeing such miserable specimens of humanity. Why hadn't Lolla-Wossiky died yet?

Just as he was about to open Harrison's door, Hooch looked up from the drunken one-eyed Red into the eyes of another man, and here's the funny thing: He thought for a second it was Lolla-Wossiky again, they looked so much alike. Only it was Lolla-Wossiky with both eyes, and not drunk at all, no sir. This Red must be six feet from sole to scalp, leaning against the wall, his head shaved except his scalplock, his clothing clean. He stood straight, like a soldier at attention, and he didn't so much as look at Hooch. His eyes stared straight into space. Yet Hooch knew that this boy saw everything, even though he focused on nothing. It had been a long time since Hooch saw a Red who looked like that, all cold and in control of things.

Dangerous, dangerous, is Harrison getting careless, to let a Red into his own headquarters with eyes like those? With a bearing like a king, and arms so strong he looks like he could pull a bow made from the trunk of a six-year-old oak? Lolla-Wossiky was so contemptible it made Hooch sick. But this Red who looked like Lolla-Wossiky, he was the opposite. And instead of making Hooch sick, he made Hooch mad, to be so proud and defiant as if he thought he was as good a man as any White. No, better. That's how he looked--like he thought he was better.

Then he realized he was just standing there, his hand on the latch pull, staring at the Red. Hadn't moved in how long? That was no good, to let folks see how this Red made him uncomfortable. He pulled the door open and stepped inside.

But he didn't talk about that Red, no sir, that wouldn't do at all. It wouldn't do to let Harrison know how much that one proud Shaw-Nee bothered him, made him angry. Because there sat Governor Bill behind a big old table, like God on his throne, and Hooch realized things had changed around here. It wasn't just the fort that had got bigger--so had Bill Harrison's vanity. And if Hooch was going to make the profit he expected to on this trip, he'd have to make sure Governor Bill came down a peg or two, so they could deal as equals instead of dealing as a tradesman and a governor.

"Noticed your cannon," said Hooch, not bothering even to say howdy. "What's the artillery for, French from Detroit, Spanish from Florida, or Reds?"

"No matter who's buying the scalps, it's always Reds, one way or another," said Harrison. "Now sit down, relax, Hooch. When my door is closed there's no ceremony between us." Oh, yes, Governor Bill liked to play his games, just like a politician. Make a man feel like you're doing him a favor just to let him sit in your presence, flatter him by making him feel like a real chum before you pick his pocket. Weil, thought Hooch, I have some games of my own to play, and we'll see who comes out on top.

Hooch sat down and put his feet up on Governor Bill's desk. He took out a pinch of tobacco and tucked it into his cheek. He could see Bill flinch a little. It was a sure sign that his wife had broke him of some manly habits. "Care for a pinch?" asked Hooch.

It took a minute before Harrison allowed as how he wouldn't mind a bit of it. "I mostly swore off this stuff," he said ruefully.

So Harrison still missed his bachelor ways. Well, that was good news to Hooch. Gave him a handle to get the Gov off balance. "Hear you got yourself a white bed-warmer from Manhattan," said Hooch.

It worked: Harrison's face flushed. "I married lady from New Amsterdam," he said. His voice was quiet and cold. Didn't bother Hooch a bit--that's just what he wanted.

"A wife!" said Hooch. "Well, I'll be! I beg your pardon, Governor, that wasn't what I heard, you'll have to forgive me, I was only going by what the--what the rumors said."

"Rumors?" asked Harrison

"Oh, no, you just never mind. You know how soldiers talk. I'm ashamed I listened to them in the first place. Why, you've kept the memory of your first wife sacred all these years, and if I was any kind of friend of yours, I would've known any woman you took into your house would be a lady, and a properly married wife."

"What I want to know," said Harrison, "is who told you she was anything else?"

"Now, Bill, it was just loose soldiers" talk; I don't want any man to get in trouble because he can't keep his tongue. A likker shipment just came in, for heaven's sake, Bill! You won't hold it against them, what they said with their minds on whisky. No, you just take a pinch of this tobacky and remember that your boys all like you fine."

Harrison took a good-sized chaw from the offered tobacco pouch and tucked it into his cheek. "Oh, I know, Hooch, they don't bother me." But Hooch knew that it did bother him, that Harrison was so angry he couldn't spit straight, which he proved by missing the spittoon. A spittoon, Hooch noticed, which had been sparkling clean. Didn't anybody spit around here anymore, except Hooch?

"You're getting civilized," said Hooch. "Next thing you know you'll have lace curtains."

"Oh, I do," said Harrison. "In my house."

"And little china chamber pots?"

"Hooch, you got a mind like a snake and a mouth like a hog."

"That's why you love me, Bill--cause you got a mind like a hog and a mouth like a snake."

"Keep that in mind," said Harrison. "You just keep that in mind, how I might bite, and bite deep, and bite with poison in it. You keep that in mind before you try to play your diddly games with me."

"Diddly games!" cried Hooch. "What do you mean, Bill Harrison! What do you accuse me of!"

"I accuse you of arranging for us to have no likker at all for four long months of springtime, till I had to hang three Reds for breaking into military stores, and even my soldiers ran out!"

"Me! I brought this load here as fast as I could!"

Harrison just smiled.

Hooch kept his look of pained outrage--it was one of his best expressions, and besides it was even partly true. If even one of the other whisky traders had half a head on him, he'd have found a way downriver despite Hooch's efforts. It wasn't Hooch's fault if he just happened to be the sneakiest, most malicious, lowdown, competent skunk in a business that wasn't none too clean and none too bright to start with.

Hooch's look of injured innocence lasted longer than Harrison's smile, which was about what Hooch figured would happen.

"Look here, Hooch," said Harrison.

"Maybe you better start calling me Mr. Ulysses Palmer," said Hooch. "Only my friends call me Hooch."

But Harrison did not take the bait. He did not start to make protests of his undying friendship. "Look here, Mr. Palmer," said Harrison, "you know and I know that this hasn't got a thing to do with friendship. You want to be rich, and I want to be governor of a real state. I need your likker to be governor, and you need my protection to be rich. But this time you pushed too far. You understand me? You can have a monopoly for all I care, but if I don't get a steady supply of whisky from you, I'll get it from someone else."

"Now Governor Harrison, I can understand you might've started fretting along in there sometime, and I can make it right with you. What if you had six kegs of the best whisky all on your own--"

But Harrison wasn't in the mood to be bribed, either. "What you forget, Mr. Palmer, is that I can have all this whisky, if I want it."

Well, if Harrison could be blunt, so could Hooch, though he made it a practice to say things like this with a smile. "Mr. Governor, you can take all my whisky once. But then what trader will want to deal with you?"

Harrison laughed and laughed. "Any trader at all, Hooch Palmer, and you know it!"

Hooch knew when he'd been beat. He joined right in with the laughing.

Somebody knocked on the door. "Come in," said Harrison. At the same time he waved Hooch to stay in his chair. A soldier stepped in, saluted, and said, "Mr. Andrew Jackson here to see you, sir From the Tennizy country, he says,"

"Days before I looked for him," said Harrison. "But I'm delighted, couldn't be more pleased, show him in, show him in."

Andrew Jackson. Had to be that lawyer fellow they called Mr. Hickory. Back in the days when Hooch was working the Tennizy country, Hickory Jackson was a real country boy--killed a man in a duel, put his fists into a few faces now and then, had a name for keeping his word, and the story was that he wasn't exactly completely married to his wife, who might well have another husband in her past who wasn't even dead. That was the difference between Hickory and Hooch--Hooch would've made sure the husband was dead and buried long since. So Hooch was a little surprised that this Jackson was big enough now to have business that would take him clear from Tennizy up to Carthage City.

But that was nothing to his surprise when Jackson stepped through the door, ramrod straight with eyes like fire. He strode across the room and offered his hand to Governor Harrison. Called him Mr. Harrison, though. Which meant he was either a fool, or he didn't figure he needed Harrison as much as Harrison needed him.

"You got too many Reds around here," said Jackson. "That one-eyed drunk by the door is enough to make a body puke."

"Well," said Harrison, "I think of him as kind of a pet. My own pet Red."

"Lolla-Wossiky," said Hooch helpfully. Well, not really helpfully. He just didn't like how Jackson hadn't noticed him, and Harrison hadn't bothered to introduce him.

Jackson turned to look at him. "What did you say?"

"Lolla-Wossiky," said Hooch.

"The one-eyed Red's name," said Harrison.

Jackson eyed Hooch coldly. "The only time I need to know the name of a horse," he said, "is when I plan to ride it."

"My name's Hooch Palmer," said Hooch. He offered his hand.

Jackson didn't take it. "Your name is Ulysses Brock," said Jackson, "and you owe more than ten pounds in unpaid debts back in Nashville. Now that Appalachee has adopted U.S. currency, that means you owe two hundred and twenty dollars in gold. I bought those debts and it happens that I have the papers with me, since I heard you were trading whisky up in these parts, and so I think I'll place you under arrest."

It never occurred to Hooch that Jackson would have that kind of memory, or be such a skunk as to buy a man's paper, especially seven-year-old paper, which by now should be pretty much forgot. But sure enough, Jackson took a warrant out of his coat pocket and laid it on Governor Harrison's desk.

"Since I appreciate your already having this man in custody when I arrived," said Jackson, "I am glad to tell you that under Appalachee law the apprehending officer is entitled to ten percent of the funds collected."

Harrison leaned back in his chair and grinned at Hooch. "Well, Hooch, maybe you better set down and let's all get better acquainted. Or I guess maybe we don't have to, since Mr. Jackson here seems to know you better than I did."

"Oh, I know Ulysses Brock all right," said Jackson. "He's just the sort of skunk we had to get rid of in Tennizy before we could lay claim to being civilized. And I expect you'll be rid of his s

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...