CHAPTER 1

Commander

To: chin.li21%

[email protected]

From: gerhard.dietrich%

[email protected]/vgas

Subject: no place for children

Colonel Li,

It has been brought to my attention that you intend to bring a group of boys between ages twelve and fourteen to GravCamp for training in zero G combat and asteroid-tunnel warfare. I will respectfully remind you that GravCamp, known officially as Variable Gravity Acclimation School, is not a school for children. It is a training facility of the International Fleet for marines. As in, grown men and women. It’s not an orphanage. Or a day care. Or a summer camp. Our facilities are not intended for the amusement of children.

Do not bring these boys here. Our position out near Jupiter puts us a good distance from the fighting in the Belt, but this is a combat zone. And war is no place for a child. The articles of the Geneva Conventions on this subject are clear. I have attached them to this message for your review. You’ll note that special protections were articulated to orphaned children under the age of fifteen. Protocols were adopted to protect children from even helping combatants. You cannot discard international humanitarian law.

Do not board your transport bound for this facility. If you do, you will be denied entry upon arrival. I won’t have a bunch of little boys scurrying around this facility like a swarm of rats. It is an affront to the dignity of men and women in uniform and a dangerous precedent within the IF. I have informed Rear Admiral Tennegard and Admiral Muffanosa of my strong objections.

Signed,Colonel Gerhard DietrichCommanding Officer, VGAS

* * *

They found the captain’s body drifting in his office with a slaser wound through the head and a mist of blood hovering in the air around him. The self-targeting laser weapon was still held loosely in his hand, and the suicide note on the terminal’s display was brief and apologetic. It took the ship’s doctor and officers over an hour to remove the body and document the scene, and by then word had spread throughout the ship and Bingwen had learned every detail.

The ship was a C-class troop transport that had left an International Fleet fuel depot in the outer rim of the Belt five weeks ago. It was bound for GravCamp out near Jupiter—the Fleet’s special-ops training facility in zero G combat and asteroid-tunnel warfare. Bingwen and the other Chinese boys in his squad were the only real anomalous passengers on board. At ages twelve to fourteen, the boys stood out sharply among the 214 marines on board headed for GravCamp. A few marines had made quite a fuss about having a bunch of boys along for the ride, claiming that war was no place for children. But several of the marines on board knew Bingwen’s squad well, having been with them when Bingwen had taken out a hive of Formics inside an asteroid and killed one of the Hive Queen’s daughters. Upon learning that, the hostile marines had shut up, and everyone had left Bingwen and the boys alone.

But now, following the captain’s death, the cargo hold where all the passengers were quartered was abuzz again with heated conversations. Everyone had a different theory on why the captain would take his own life. The prevailing—and unfounded—belief was that the captain had simply “space-cracked,” that the isolation and emptiness of space, compounded by the daily depressing reports on the war coming in via laserline, were too much for the man to handle.

Bingwen didn’t buy that theory. In his sleep capsule that evening, he hacked into the ship’s database and accessed the incident report and autopsy, neither of which put his mind at ease. The medical examiner suggested that the captain had a hidden history of mental illness and perhaps suffered from an untreated case of PTSD stemming from a previous incident in the war. Bingwen’s review of the captain’s service records revealed that he had recently captained a warship in the Belt but had lost his commission after he had failed to aid another warship requesting assistance, resulting in the death of over two hundred crewmen. Based on what Bingwen read, the captain was lucky he hadn’t been court-martialed for violation of Article 87 of the International Fleet Uniform Code of Military Justice, on wartime charges of acts of cowardice. Someone up the chain had given the captain a break and made him the captain of a transport rather than force him to face a tribunal.

Yet even that didn’t sit well with Bingwen. Had the man killed himself out of guilt? Out of shame?

The following morning Bingwen gathered with the rest of the marines in the main corridor. A funeral march played over the speakers as a few members of the ship’s permanent crew carried the body tube toward the airlock. Once the captain’s remains were secured inside the airlock, one of the officers read a few verses from Christian scripture and offered a prayer. The ship’s former XO, who was now the new captain, signaled for the loadmaster to open the exterior hatch. Bingwen watched as the body tube launched away silently with a burst of escaping air, spinning end over end until it was lost from view.

Slowly, as if not wanting to be the first to leave, the officers solemnly dispersed and returned to their posts. The passenger marines quickly followed suit. Bingwen and the boys in his squad lagged behind, watching the airlock as if they thought the captain might rematerialize.

“Good riddance, I say,” said Chati.

Nak looked horrified. “Have you no respect for the dead? Or your elders? You shame yourself and China.”

The boys, like Bingwen, were all orphans, recruited out of China by Colonel Li during the first war. They had each scored exceptionally high on tests designed to identify strong potential for military command. More impressive still, they had survived Colonel Li’s aggressive combat and psychological training, or as Nak called it: Colonel Li’s Totally Deranged and Borderline Psychotic Military School of Abuse for Orphans.

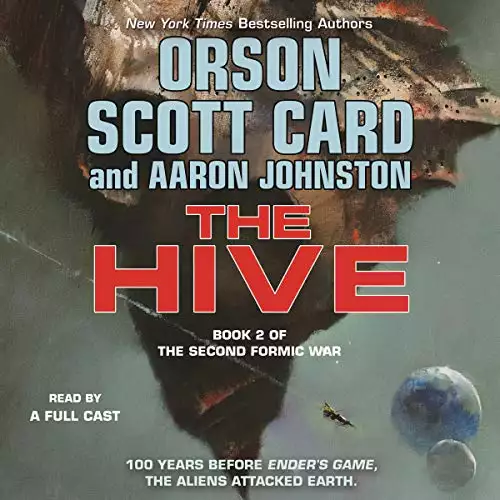

Copyright © 2019 by Orson Scott Card and Aaron Johnston

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved