- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

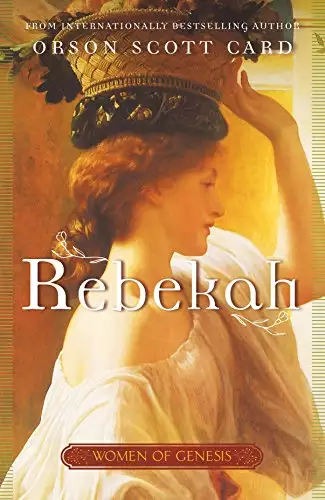

Rebekah, book two in bestselling author Orson Scott Card's Women of Genesis series-a unique re-imagining of the biblical tale.

Born into a time and place where a woman speaks her mind at her peril, and reared as a motherless child by a doting father, Rebekah grew up to be a stunning, headstrong beauty. She was chosen by God for a special destiny.

Rebekah leaves her father's house to marry Isaac, the studious young son of the Patriarch Abraham, only to find herself caught up in a series of painful rivalries, first between her husband and his brother Ishmael, and later between her sons Jacob and Esau. Her struggles to find her place in the family of Abraham are a true test of her faith, but through it all she finds her own relationship with God and does her best to serve His cause in the lives of those she loves.

Women of Genesis

Sarah

Rebekah

Release date: July 17, 2018

Publisher: Tom Doherty Associates

Print pages: 432

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Rebekah

Orson Scott Card

Rebekah’s mother died a few days after she was born, but she never thought of this as something that happened in her childhood. Since she had never known her mother, she had never felt the loss, or at least had not felt it as a change in her life. It was simply the way things were. Other children had mothers to take care of them and scold them and dress them and whack them and tell them stories; Rebekah had her nurse, her cousin Deborah, fifteen years older than her.

Deborah never yelled at Rebekah or spanked her, but that was because of Deborah’s native cheerfulness, not because Rebekah never needed scolding. By the time Rebekah was five, she came to understand that Deborah was simple. She did not understand many of the things that happened around her, could not grasp many of Rebekah’s questions and explanations. Rebekah did not love her any the less; indeed, she appreciated all the more how hard Deborah worked to learn all the tasks she did for her. For answers and understanding, she would talk to her father, or to her older brother Laban. For comfort and kindness she could always count on Deborah.

Rebekah no longer played pranks or hid or teased Deborah, because she could not bear seeing her nurse’s confusion when a prank was discovered. Rebekah soon made her brother Laban stop teasing Deborah. “It’s not fair to fool her,” said Rebekah, which made little impression on Laban. What convinced him was when Rebekah said, “It’s what a coward does, to mock someone who can’t fight back.” As usual, when she finally found the right words to say, Rebekah was able to prevail over her older brother.

The real change in her life, the one that transformed Rebekah’s childhood, was when her father, Bethuel, went deaf. He had not been a young man when she was born, but he was strong enough to carry her everywhere on his shoulders when she was little, letting her listen in on conversations with the men and women of his household, shepherds and farmers and craftsmen, cooks and spinners and weavers. Riding on his shoulders as she did, his voice became far more than words to her. It was a vibration through her whole body; she felt sometimes as though she could hear his voice in her knees and elbows, and when he shouted she felt as if it were her own voice, coming from her own chest, deep, manly tones pouring out of her own throat. Sometimes she resented the fact that in order to say her own words, she had only her small high voice, which sounded silly and inconsequential even to her.

But when she spoke, Father heard her, and since he was the most important man in the whole world, however weak her voice might be, it was strong enough. Even after she grew too big to ride his shoulders, she was at his side as much as possible, listening to everything, understanding or trying to understand every aspect of the life of the camp, the work and workings of the household. He, in turn, called her his conscience. The little voice always at his side, never intruding, but asking him wise questions whenever they were alone together.

And then, trying to keep a cart from sliding down a muddy bank into the cold water of a brook in spring flood, Father slipped himself and fell into the water, the cart tumbling after him. The men swore later that it was a gift of God that Bethuel was not killed, for the cart was held up by the spokes of its own broken wheel just enough that he was able to keep his mouth above water and breathe while the men hurriedly unloaded the cart enough that they could lift it off him. He seemed at first to be no worse the wear for the hour he spent in the cold water, but that night he awoke shivering and fevered, and for two weeks he came back and forth between fever and chills as if the icy water still had a place in him.

When he rose at last from his pallet, the world had gone silent for him. He shouted everything he said, and heard no one’s answer, and when Rebekah ran to him and covered her ears and cried, “Father, why are you angry with me?” he bent down to her and shouted for her to speak up, speak up, he couldn’t hear her. Louder and louder she spoke until she was red-faced with screaming and Father gathered her into his arms and wept. “Of all the sounds that I shall never hear again,” he murmured into her hair, “the voice of my sweet girl is the one I will miss most of all.”

Father remained master of his household, but there was no more ranging out in the hills to oversee the herds. There was too much danger to a man who could not hear a shouted warning, or the roar of a lion, or the cries of marauders. Instead, Father had no choice but to trust his servants to oversee his flocks and herds. It embarrassed him to have to ask people to repeat everything, to talk slowly, to pronounce their words carefully so he could try to read their lips. He did not have to tell Rebekah that she could not stay with him all the time that he was in camp, as she had used to. She could see that he did not want her there, partly because he was ashamed to show his weakness in front of her, and partly because, when she spoke to him, she saw how much it hurt him that he could not hear her anymore.

“Why don’t you go with your father?” Deborah asked her. “He likes you beside him. He used to carry you when you were little. You’re too big now.”

Rebekah had to explain it to her several times. “Father is deaf now. That means he can’t hear. So I can’t talk to him anymore. He doesn’t hear me.”

And after a little while, Deborah understood and remembered. Indeed, she took to informing Rebekah. “You mustn’t go to your father today. He’s deaf, you know. He can’t hear you when you talk to him.” Rebekah didn’t have the heart to rebuke Deborah for the frequent reminders. Instead, she would ask Deborah to sing her a song as she plaited Rebekah’s hair or spun thread beside her or walked through the camp, looking at the work of the women and children and old men. Everyone looked up when Deborah came singing, and gave her a smile. And they smiled at Rebekah, too, and answered her questions, until she understood everything she saw going on, all the work of Father’s household.

Rebekah was ten years old when Father lost his hearing, and her brother Laban was twelve. It was just as hard on him as it was on her, for as she had been Father’s constant companion in the camp, Laban had been his shadow on almost every trip to visit distant flocks and herds where they grazed.

To Laban it was like a prison, always to be in camp because his father rarely traveled. And Rebekah was no happier. Once she would have rejoiced to have Father always near the home tents, but he was short-tempered now, and bellowed often for no good reason.

Everyone was ill at ease. But the work of the household went on, day after day, week after week. People get used to anything, if it just goes on. Rebekah didn’t like the way things were, but she expected this new order to go on unchanged.

Until, a year after her father’s deafness began, she happened to come up behind several of the servant women boiling rags, and overheard them talking about Father.

“He’s an old lion, with all that roaring.”

“A lion with no teeth.”

And they started to laugh until one of them noticed Rebekah and shushed the others.

Rebekah told this to Laban, and at first he was all for telling Father. But Rebekah clutched at Laban and held him back. “How will you even tell him? And if you make him understand, then what? Should he beat the woman for saying it? Or the others for laughing? Will that make them love him better?”

Laban looked at her. “We can’t let them laugh at Father behind his back. Soon they’ll laugh in his face, and then they’ll do what they want. Already the servants don’t even try to tell Father half the things that happen. Pillel makes decisions all by himself that he used to never make, and Father knows it but what can he do?”

“We can pray to God for him to hear again,” said Rebekah.

“And what if God answers us the way he answered Abram and Sarai when they prayed for a son? Can Father wait ten years? Twenty? Thirty?”

They knew well the tales of their father’s uncle Abraham, the great lord of the desert, the prophet that Pharaoh could not kill, and how his wife Sarah bore him a baby in her old age.

“But what else can we do?” said Rebekah. “Only God can let Father hear again.”

“We can be his ears,” said Laban. “We have time to explain things to him. Let the men tell us, and we’ll tell Father.”

Rebekah had her doubts about this. She had tried talking to Father many times, speaking slowly so he could read her lips, and at first he had tried to understand her, but most of the time he failed, or got it only partly right, and the resignation in his eyes when he looked away from her and refused to try anymore made her so sad she couldn’t even cry. “What, you’ll press your mouth into his ear and scream?”

Laban rolled his eyes as if she were a hopeless simpleton. “Writing.”

“That’s a thing for city priests.”

“Uncle Abraham writes.”

“Uncle Abraham is far away and very old and spends all his time talking to God,” said Rebekah.

“If the priests in the city can write, and Uncle Abraham can write, then why can’t Father and I learn to write?”

“Then I can, too,” said Rebekah, daring him to argue with her.

“Of course you can,” said Laban. “You have to. Because as soon as I can, I’ll be out with the men, and you’ll have to be able to talk to Father, too.”

For three days, Laban and Rebekah spent every spare moment together, working out a set of pictures they could draw with a stick in the dirt. Some of the words were easy—each of the animals could be drawn quickly, as could crops, articles of clothing, pots, baskets. Day and night were easy enough, too—the sun was round, the moon a crescent. Water was a bit more of a challenge, but they ended up with a drawing of a well.

“What if you want to say ‘well’?” asked Rebekah.

“Then I’ll draw a well,” said Laban.

“What if you want to say, ‘There’s no water in the well’?” asked Rebekah.

“Then I’ll draw a well, point to it, and then rub it out!” Laban was beginning to sound exasperated.

“What if you want to say, ‘The well has been poisoned’?”

Laban pointed to his well drawing and then pantomimed gagging, choking, and falling down dead. He opened his eyes. “Well? Do you think he’ll get it?”

“That can’t be the way Uncle Abraham does it,” said Rebekah.

“We aren’t trying to write to Uncle Abraham,” said Laban. “We’re just trying to talk to Father.”

“What if you want to say, ‘I’m afraid there might be bandits coming but Pillel says they’re just travelers and there’s nothing to worry about but I think we should gather in the men and sleep with our swords’?”

Laban glared at her. “I will never have to say that,” he said.

“How do you know?”

“Because I would just … I would just tell him that bandits were coming and bring him his sword.”

“No!” shouted Rebekah. “The men would know it was you who decided and not Father. And they can’t follow Father into battle anyway, so it would have to be Pillel in command at least until you’re tall enough to lead the men yourself, and anyway the whole idea of this is to help Father keep the respect of the men, and if you aren’t telling him the truth and letting him decide then they won’t respect him or you and they won’t trust you either and then we’ve lost everything.”

It was obvious Laban wanted to argue with her, but there was nothing to say. “Some things are just too hard to draw,” Laban finally admitted. “But you’re right, we have to try.”

“I think writing isn’t worth much if you have to be right there to make faces or fall down dead,” said Rebekah.

“There’s a trick to it that we don’t know.”

“If priests who are dumb enough to pray to a stone can do it,” said Rebekah, “we can figure it out.”

“If we make fun of their gods, people in the towns will shut us out,” Laban reminded her. It was one of the rules learned by those who moved from place to place, following green grass and searching for ample water.

Rebekah knew the rule. “I was making fun of the priests.” She looked again at Laban’s drawings in the dirt. “Let’s show Father as much as we’ve figured out about writing.”

“I don’t want to show him until we have it right.”

“Maybe he can help us get it right. Maybe he knows how Uncle Abraham does it.”

“And in the meantime, how will I draw a picture of us not knowing how to draw pictures of things we can’t draw pictures of?”

“If you draw something and he doesn’t understand, then at least he’ll understand that we don’t know how to make him understand, and that’s what we’re trying to make him understand.”

Laban grinned. “Now you’re sounding like a priest.”

Rebekah laughed. “The Lord is not made of stone, he is in the stone. The Lord is not confined by the stone, he is expressed by the stone. Since the Lord was in the stonecutter who shaped the image, the idol is both man’s gift to the Lord and the Lord’s gift to man.”

Laban whistled. “You listen to that stuff?”

“I listen to everything,” said Rebekah. Her own words made her think of Father, who could never listen to anything again.

“I listen to everything, too,” said Laban. “But you remember it.”

“That has to be the worst thing for Father,” said Rebekah. “That he remembers being able to hear. Being at the center of everything.”

“What, you think it would have been better if he had always been deaf? Who would have married him, then? Who would be our father?”

“Father would,” said Rebekah. “Because Mother would have loved him anyway.”

“But Mother’s father would never have given her to a deaf man in marriage.”

“She would have married him anyway!”

“Now you’re just being silly,” said Laban. “Would you marry a … a blind man? A cripple? A simpleton?”

“I would if I loved him,” said Rebekah.

“That’s why fathers decide these things, and don’t leave them up to silly girls who would go off and marry blind, deaf, staggering fools.”

Laban said this so loftily that she had to poke him. “But Laban, someday Father will have to find a wife for you.”

“I’m not a … I don’t … I refuse to let you goad me.”

Rebekah laughed at his dignity. “Let’s go show Father as much writing as we’ve got.”

“I don’t want him to see how bad we are at it.”

“The only way to get better is to do it wrong till we get it right. Like you with sheep shearing.”

Laban blushed. “You really do remember everything.”

“I remember eating lots of mutton,” said Rebekah. “I remember you wearing an ugly tunic woven out of bloody wool.”

“You were only a baby.”

“Come on,” she said, pulling him toward the brightest-colored tent that marked the center of their father’s household.

They did not clap their hands outside the tent, or call out for permission to enter—what good would it have done? That was one of the things Rebekah knew Father hated worst—the fact that people now had no choice but to walk in on him at whatever hour they thought their need was more important than his privacy. Or his dignity. He had tried keeping a servant at his door, but either his visitors ignored the servant or the servant kept out people Father needed to see, and besides, it was not as if the household could afford to keep a man away from his real work just to sit at the master’s door all day. So Laban parted the tent flap and peered inside.

Father was going over tally sticks with Pillel. Because Rebekah knew that Pillel had just been to the hills south of the river, she knew that the sticks were a count of the main goat herd, and from the number of marks below the main notch she knew that it was a good year, with many new kids thriving. Last winter’s rains had washed away dozens of houses built on land that had been dry through two generations of drought. But the hillsides were lush this spring, and the herds and flocks were fat and strong; and if there could be rains again this winter, they might not have to sell half the younglings into the towns for slaughter, but could keep them and grow the herds and become wealthy again, wealthy as in the days when Abraham had been a great prince whose household was so mighty he could defeat Amorite kings and save the cities of the plain.

Only she would trade such wealth and power, would trade even the herds they had, would give up the whole household and labor with her own hands at all tasks, hauling water like a slave and wearing only cloth she wove herself, if Father could only hear again.

Though of course that was a childish thing to wish, because if Father could hear, then he would have his great household and all his flocks and herds and there’d be nothing to fear. No, the way the world worked, you didn’t trade wealth to get wholeness of body. It was when your body ceased to be whole that you also lost your wealth, your influence, your prestige, everything. It could all go away—would all go away, once something slipped. Everything we have in life, Rebekah realized, depends on everything else. If you lose anything, you can lose everything.

So do we really have anything at all? Was that what God was showing them by what he had allowed to happen to Father?

Only Father had not lost everything. Had not really lost anything yet. Pillel was still serving Father, wasn’t he? And Pillel was keeping everything together.

But didn’t that mean that now the herds and flocks and the great household belonged to Pillel? Out of loyalty, he served Father—but the men served Pillel. And there would come a day, surely, when Pillel would see the great dowry Father would assemble for Rebekah and wonder why his daughters had nothing like it to offer a husband, or when Pillel would look at Laban and wonder why the son of the deaf man was going to inherit everything Pillel had created instead of his own strong sons.

Why was she thinking this? Pillel would never betray them.

And yet how was it better that all of Pillel’s labor, all his life, should belong to another man? Why shouldn’t he be able to pass along great flocks and herds to his sons? Instead he would give them only the yoke of servitude, though his life’s work had created great wealth. It was not fair to him, or to his sons. Any more than it was fair to Bethuel to be deaf.

A thought came to the verge of her mind. About fairness, about the way God deals with people. It was a thought tinged with anger and fear, but also with that thrill that came when she finally understood something that mattered. But as quickly as it came, the thought escaped her without her being able to name it, without her being able to hold it.

Wrong, Laban, I don’t remember everything. The best things, the ideas that matter most, they slip away without my ever really having them.

Again the important thought verged on understanding. Again it fled unnamed.

Bethuel saw Laban and Rebekah because Pillel heard them and looked up and beckoned them to come all the way in.

“Ah, my children!” boomed Bethuel.

His voice was so loud, now that he was deaf. Though she knew he could not help it, it still made Rebekah a little ashamed when he boomed out his words at inappropriate times. Father could keep no secrets now.

“I’m done here,” said Pillel. He rose, gathering up the tally sticks.

“The goats are doing well this spring,” said Laban.

Pillel grinned. “The billies were frisky last fall.”

“Or the nannies were too lazy to run away,” said Laban.

Pillel glanced nervously at Rebekah. She hated it when people acted like that. Just because she was the daughter of the house and her purity had to be protected did not mean she was blind and did not know how lambs and kids and calves were made.

“You can stay,” said Rebekah.

“No, he can’t,” said Laban, annoyed.

“Only your father bids me stay or go,” said Pillel mildly. “And he has asked me to leave.”

Rebekah looked sharply at him. Father had said no such thing. But there were many things Pillel and Father were able to communicate without words—there always had been. A glance, a wink, a tiny gesture; they understood each other so well that words were often unneeded. Of course that had not changed with Father’s deafness. But what was to stop Pillel from claiming that Father had told him something when it was merely Pillel’s own decision?

Trust, that’s what. Pillel had earned the family’s trust, and just because he could lie did not give Rebekah any right to suppose that he would. When a man had earned their trust, he ought to have it, and not lose it just because a foolish girl noticed that he could probably get away with any number of small betrayals.

When Pillel was gone with the tally sticks, Laban wasted no time. He pulled back three layers of rugs to expose a patch of hard sandy soil. Rebekah watched Father as Father watched Laban draw his pictures. He grew more and more puzzled, and Rebekah could not help agreeing with him.

“What are you drawing?” she whispered. “This isn’t anything we worked out together.”

“I’m trying a new one,” he said.

“Well I can’t understand it.”

Angry, Laban rubbed out the drawing with his sandal and began again. This time he drew the symbols that they had worked out for saying what was being prepared for dinner. The fire, the spit, the pot. Only this was absurd. They hadn’t even been to the kitchen fires today. “Laban, what are you doing? We don’t know what’s for dinner.”

“I’m not telling, I’m asking,” said Laban. “What he wants. And then we can go tell the women.”

He turned to Father, who was studying Laban’s drawing with an odd expression. Laban waved a hand down within Father’s field of vision, and Father looked up at his face. Laban elaborately mouthed his words.

“Dinner,” Laban said, then pointed at the parts of the drawing. “Food. Dinner. Kitchen. Cookfire. The pot. The spit. See?”

“If you use all the different words, how will he know what each picture means?”

Laban whirled on her. “If you think you can do better, give it a try!”

“Yes, I will,” she said. Taking the stick from Laban’s hand, she began her own drawing. She drew a tall man, a short man, and a short girl. She pointed to Father, Laban, and herself, then back at the drawings.

Father nodded. That was more than he had done with Laban’s drawing, but she did not look at Laban lest he think she was being triumphant. He got huffy when he thought he had been shown up.

Rebekah rubbed out her pictures, then drew just the boy and girl, and this time the girl had a stick in her hand and under the point of the stick Rebekah drew a very tiny picture of the very picture she was drawing—the boy, the girl, the stick.

Father chuckled.

But Rebekah wasn’t done. She drew a picture of an ear, then scribbled across it. Then a picture of an eye, and a dotted line going to it from the drawing the girl was making.

Then she knelt before Father and mouthed her words carefully. “I draw. You see. That is how you hear us.” She touched the picture of the eye, then reached up and touched Father’s ear. Then his eye, then his ear again. “You see, and that’s how you’ll hear.”

Father shook his head.

He didn’t understand.

No, he did understand. Because he wasn’t just shaking his head. He was smiling, then laughing, but it was a rueful, affectionate laugh, and he gathered Rebekah into his arms and then reached out for Laban as well and embraced them both. “My children, wonderful and wise.”

“He likes it!” said Laban.

Father must have felt the vibration of Laban’s voice, because he pulled back and looked expectantly at Laban’s face.

“It’s writing,” Laban said. “Like Uncle Abraham.”

Father wrinkled his brow—he didn’t understand Laban’s words. But it hardly mattered, since the next thing he said was, “It’s writing. You’re trying to write to me.”

“Yes,” said Rebekah, and Laban almost jumped out of his clothes in his excitement, jumping up and down, obliterating the drawings with his feet.

“But you don’t do it with pictures of the thing,” said Father. “You make pictures of the sounds.”

Father reached out a hand. After only a moment’s hesitation, Rebekah realized he wanted the stick and gave it to him. He thought for a long moment, then made three marks in the dirt.

“You make marks that stand for the sounds of the word,” he said. “That’s your name, Rebekah.”

“It doesn’t look like anything,” said Laban.

Father didn’t hear him, but explained anyway. “This mark is always ‘ruh.’ And this mark is always ‘buh.’ And this one is ‘kuh.’”

He made three more marks. “‘Luh,’ ‘buh,’ ‘nuh,’” he said.

“Look, your name and mine are the same in the middle,” said Rebekah.

“But my name isn’t ‘luhbuhnuh,’ it’s Laban.”

Father was studying their faces, as usual, and saw Laban’s resistance.

“We just write down the solid sounds,” Father said. “The ones that don’t change. The Egyptians do it foolishly, and so do the Babylonians and Sumerians—the priests have a separate picture for every possible sound. Bah, beh, bo, bee, boo, bim, ben, ban—a separate picture. So you have to learn hundreds and hundreds in order to write anything. But we use the same mark for all the ‘buh’ sounds. ‘Bah,’ ‘beh,’ ‘bo,’ ‘bee,’ ‘boo,’ we just make this mark. ‘Bim,’ ‘ben,’ ‘ban,’ we make the same mark but we add this one, for the sound of the nose. See? Look, I’ll show you.”

Using just the marks from their names, he wrote them in several different combinations, then said the words. Sometimes the same two or three symbols stood for two or three or four different words at the same time. “But it doesn’t matter,” he said. “Because one word will make sense and the others won’t. So you always know which is which. And if you don’t, then you just add a word so we know which one you mean.”

Rebekah’s head was reeling. She started making sounds with her lips and tongue and trying to count them. “Kuh buh muh tuh chuh nuh guh luh…”

Father saw what she was doing and stopped her with a touch. “I’ll show you all of them that I remember. I learned this when I was a boy, you understand. I haven’t used it much since then. There was no one to write to, and nothing to read. I never taught it to you because it was so useless. I almost forget that I had ever learned it.” He laughed bitterly. “It was for sacred writings. Tally sticks are enough for counting goats and sheep, which is all I’ve ever needed. Abraham had all the ancient writings. Once he had a son, I knew his boy would have the holy birthright and there was no more need for me to remember how to write. Was my son going to be a priest? I never thought of using writing for something else. For myself.”

Rebekah heard him, but her mind also raced in its own direction. “But this means we can write anything,” she said. “If we can make the word with our mouths, we can write it down, once we know all the marks.”

Father must have read enough from her lips to know what she was saying. “I’ll teach them all to you, all that I remember. This is a good idea, children. You can write to me to tell me what I need to know. It’s too hard to read lips. Too many sounds come from the back of the mouth. Everybody talks too fast. Or they shape their mouths so queerly when they’re trying to talk to me. But this way—you’ll give me my ears again!”

Then he frowned. “But I don’t know if I should teach you, Rebekah.”

“Why not?” she asked. Trying not to overshape the words. Trying not to say them too fast. Trying not to show how indignant she was at the idea of being left out.

Father calmed her with a hand on her arm. “No, you’re right, Rebekah. It was always for the boys. Writing was part of the birthright. The keeper of the ancient writings had to know it. But now we’re going to use it so you can ask me what I want for dinner. Of course I must teach you, Rebekah.”

They set to work learning the alphabet. At first Father could remember only about two-thirds of the letters. But by the time they had been writing messages to each other for several days, Father remembered them all, or at least remembered signs that worked well enough. And as long as they all remembered the same signs for each sound, what did it matter if they were exactly the same as the ones Abraham used on the sacred books? Uncle Abraham was far away and very old, if he wasn’t dead already.

Of course the servants and freemen of the household saw what they were doing and how these marks allowed Bethuel to speak aloud the words that others were trying to say to him. When Laban saw this, he tried to close the others out by rubbing out the marks when he was done, or concealing them from view with his body. At first Rebekah followed his lead and tried to keep the secret from the other children and the women who were the first to try to learn. But then she remembered how she had felt when Father suggested that he might not teach her how to read and write the letters.

Why should anyone be shut out o

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...