- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

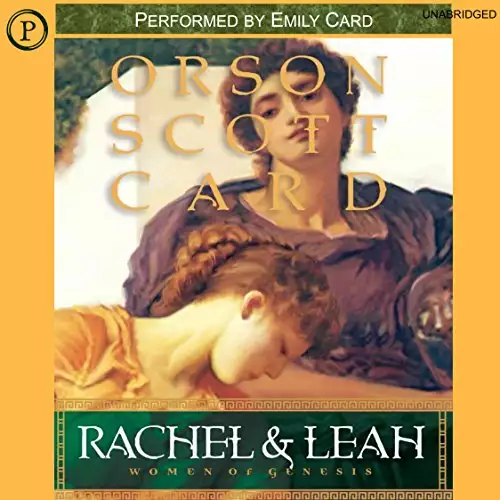

Beginning with Sarah and Rebekah, Rachel and Leah is book three of bestselling author Orson Scott Card's Women of Genesis series-a unique reimagining of the biblical tale

Tracing their lives from childhood to maturity, Card shows how the women of Genesis change each other-and are changed again by the holy books that Jacob brings with him.

Leah, the oldest daughter of Laban, whose "tender eyes" prevent her from fully participating in the daily work of her nomadic family, and Rachel, the spoiled younger daughter, the petted and privileged beauty of the family-or so it seems to Leah.

There is also Bilhah, an orphan who is not quite a slave but not really a family member, a young woman desperately searching to fit in, and Zilpah, who knows only how to use her beauty to manipulate men as she strives to secure for herself something better than the life of drudgery and servitude into which she has been born.

Into the desert camp comes Jacob, a handsome and charismatic kinsman who is clearly destined to be Rachel's husband. But that doesn't prevent the other women from vying for his attention.

Ambition, jealousy, fear, and love motivate them as they vie for the attention of Jacob, heir to the spiritual birthright of Abraham and Isaac.

Release date: November 13, 2018

Publisher: Tom Doherty Associates

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Rachel and Leah

Orson Scott Card

Bilhah was not born a slave. Her father was a free man, the son of a free man. He had skill, too. His fingers could fly over the pots of tile and find just the right color and he’d know just what size and shape it needed to be and he could tap just so on the tile and the right piece would chip off and he’d set it in the mortar.

It all looked like dots of color to Bilhah, watching him as a little girl. But when the day’s work was done and he picked her up and carried her away, she’d look back over his shoulder and all the little bits of colored tile would suddenly be something. A horse, a lion, two men fighting, a beautiful woman, all made out of little bits of tile that had looked like nothing at all up close.

It was a miracle, to Bilhah. Her father worked miracles every day, for hours and hours, working too close to see the picture he was making, and yet it was always there, he never made a mistake. He was the best at such work in all of Byblos, Bilhah heard a man say that once, and she believed it.

Best in Byblos. And if that was so, then he must be best in all the world, because didn’t the ships come over the sea from Egypt and all the islands? Why would they come to Byblos except that Byblos had the best of everything?

Mama wasn’t born a free woman like Papa. She was a slave in a rich man’s house. And a young one, when Papa met her—she told Bilhah the story many times. “I so young that nobody laying a hand on me yet, but your papa, he come to the house of my master and my master say, You make a picture here, you make a picture there, how much you want me to pay? And your papa he say, I just want one thing. I want that little Hittite girl you got there. And my master he say, She too young. And Papa say, You give me her, I set her free, and she get old enough, I marry with her. And then he do his most beautiful work, and I think I see my own face in it three time, and when he finish, my old master come to him and say, Well you take her, because you give her to me three time in these pictures, so I give you one, I make a profit. And your papa take me away and put me in his mama house and he say, This girl be my wife some day, you teach her, Mama. And his mama teach me like she my own mama, and now I talk fine like this and I a free woman, and you grow up free all your life.”

That was the promise of Bilhah’s childhood. Then Mama died giving birth to a baby boy who died the next day, and that’s when Bilhah started going to her father’s work with him. Every day, learning more and more how to help him, and then at home, they cooked together and ate together, and she talked about everything and he answered her questions, and he often told her, “Someday, my beautiful girl, all the boys in Byblos will come to me saying, I don’t want a picture, I want that little girl of yours, and I’ll say, You can’t have her, she’s my little girl forever.”

“I’ll be big then, Papa.”

“Always my little girl, no matter how big you get,” he said.

And then one day the king’s men rode hard through the market and a man pulled his heavily loaded donkey out of the way, not seeing that Bilhah and her father were beside the animal. Bilhah tried to dodge out of the way, but she bumped into the wall of a house and the donkey bumped her from the other side and she couldn’t find a way past the donkey’s legs because it was stamping and snorting. And then she felt her father pulling her away, yelling at the donkey man. Then the donkey lurched again and Papa stopped yelling and after a couple of minutes his fingers let go of her and when the donkey moved away from the wall, Papa fell down.

The donkey man never saw what he did. Papa lay there dead in the street and people stepped over him while Bilhah cried, until finally along came a man who knew them. He was a man that Papa had once taught to work the tile, but he had no talent for it and now he made harnesses for animals. But he still knew Papa and he said to Bilhah, “Can you hold to my robe while I carry your papa back to the house?”

Of course she could. She was eleven years old, she wasn’t a baby anymore! Couldn’t he see that? She wasn’t crying like a little lost baby, she was crying because her papa was dead saving her from the stupid donkey, crushed and broken against a wall by the donkey’s load. Wasn’t that a good cause to cry?

The friend picked up Papa’s body and carried him back to their little house, Bilhah clinging to his robe the whole way. She watched as the man laid Papa on the bed and covered him so gently. “What will happen now?” she asked him.

She meant, What will happen to Papa. But he answered her as if she meant, What will happen to me. “I know your father has a cousin who works for a man in Haran.”

“But Haran is far from the sea, and Uncle No isn’t a free man. He ran into debt and when he couldn’t pay, he sold himself and now he’s a servant.”

“I know,” said the man.

“If I go live with him, then I won’t be the daughter of a free man, I’ll be in the house of a servant and I’ll have to be a servant, too.”

“That’s if you’re lucky,” said the man. “What if the master says, No, we’ve got no room for a little girl like this”?

Only then did Bilhah realize that with no father, with no mother, she would belong to a stranger, and become what that stranger was. A cousin she had never met, but only heard Papa and Mama talk about years ago, clucking their tongues and tugging at their clothing to show their grief for the poor man, who sold himself into slavery to pay his debts. And now she would have to share his lot.

“No,” she said.

“Yes,” said the friend. “You don’t know, Bilhah, but in this city a girl like you, with no family, your life would be terrible and short.”

“You be my family,” she said.

“I can’t,” he said. “I’m only a harness maker, and no kin of yours.”

“Marry me,” said Bilhah. “Like my father married my mother, and then waited for her to grow up. Papa says I look like Mama, I’ll grow up to be beautiful like her.”

“I can’t,” said the man.

“Look,” she said, and ran to the corner of the workroom and pulled and pulled at the big basket of tile chips until the man finally helped her move it, and then dug in the floor under the spot where it had been until she found all of Papa’s money, the precious coins that he always told her would be her dowry.

“Here,” she said. “My dowry. You take it and marry me and let me stay in Byblos. Don’t make me go be a slave among herdsmen!”

“No,” said the man. “No, that money isn’t for your husband—a beautiful girl like you, men will someday pay a bride-price for you, and not a small one. That money is your own, to take into your marriage so your husband will never have power over you.”

“No one will pay a bride-price for a servant girl.”

“They will for you,” the man said. “But let me take these four coins, to pay for the burying of your father. Two for the land where he will lie, one for the man who digs the grave, and one for the priest of Ba’al who will send him on his way to God.”

“Then take only three,” said Bilhah. “Papa did not serve Ba’al.”

The man shook his head. “But the people who tend the graves do,” he said, “and if the grave is not watched over by Ba’al, then soon his body will be taken out and the space sold again to someone else.”

Bilhah had not known there was anyone in the world evil enough to do such a thing. But she saw in his face that he wasn’t lying. “Four, then,” she said. “Or five. For two priests.”

“One is enough,” he said. “And don’t show this to anyone else. This hiding place, this dowry.”

That night, neighbor women and the wives of some of Papa’s friends took turns keeping vigil and keening over Papa’s body, and at dawn the other tile workers, some who had been young men when Papa was young, and some who had learned from him after he became a master, carried him to the grave and laid him in it and Papa’s friend gave a coin to the digger and then he and Bilhah stayed to watch him fill the grave with dry dirt.

Bilhah piled stones at her father’s head, like putting a seal on a letter as the scribes did in the market. She memorized how the stones were, so she would know if they had been moved, if the body had been taken. And she looked long and hard at the digger, who nodded as if to say, I see that you will remember your father’s gravestones, and I will make sure no one disturbs this place.

By noon the friend had her sitting on the back of a donkey. “The man who owns this beast, he gave me the use of her for three days, and I’ll give him the harness work for free, so it costs me nothing.”

“It costs you the time making the harness,” said Bilhah, who understood perfectly well the sacrifice he was making. “That and the cost of the leather and brass, too.”

“All that I know of hard work and honorableness, I learned from your father,” he said. “Taking care that you are cared for, that is how I discharge my debt to that good man.”

And at those words, Bilhah wept quietly on the donkey’s back as the man led them out of the east gate of Byblos and took her on the dry, winding road up into the hills. She looked back again and again, watching as Byblos first grew very large, and then grew smaller and smaller, until there came a time when she could not see the city for the dazzle of sunlight from the sea beyond it.

Then even the sea was gone. She was surrounded by scrub oak and the occasional cypress tree, and the dust of the road clogged her nose and made mud of the tears on her cheeks.

Twice, chariots of the king’s men came clattering along the road, once going up, once going down, raising a fearsome dust and forcing everyone off the road as they passed.

But when she complained, her protector only laughed at her. “It is because of those soldiers that we can travel like this, just you and me and a donkey. If no soldiers came by, then there would be brigands after us—they used to live in these hills thicker than lions—and soon I’d be dead and the donkey and you would both belong to them until they saw fit to sell you.”

Bilhah shuddered at the thought.

Not long afterward, though, she realized that, going to live in a servant’s care, she was entering slavery as surely as if brigands had taken her. The only benefit was that there would probably be less suffering along the way. And, of course, she had her dowry, tied up in a cloth and carried over her friend’s shoulder because, as he explained, What if the donkey runs away or is stolen or falls off a cliff? Should he take your dowry with him when he goes?

They slept at a little inn where once again, apparently, the man had done harness work and there was no mention of paying. They had a good meal of lentils and carrots and old goat in a stew, and her friend slept at her feet with his knife in his hand, lest some rough traveler think that she was unprotected.

It was only two hours farther to Padan-aram, where her cousin’s master camped. They did not pass the town of Haran—it lay on the other side of Padan-aram, said her friend. “But you will have plenty of chances to see it, I’m sure,” he said.

The camp was not as bad as she had feared. Only a few of the dwellings were tents. The rest were houses of stone, along with pens for animals and stone-and-stick sheds for storing this and that. A much more permanent place than she had thought a “camp” would be, though it was nothing at all like the crowded, busy streets of Byblos.

They were seen coming in. A man walked out to greet them—only one man, which her friend said was a good sign. “They’re peaceful people here,” he said. “That bodes well for you.”

Her friend explained why they had come, as Bilhah modestly kept her eyes averted from the stranger.

And within a few minutes, she had met her cousin Noam (who, she quickly learned, did not like being called “Uncle No”), and then met the great man, Noam’s master, called Laban.

“Have you any skills?” asked Laban.

“I can mix the mortar as well as ever my father could,” she said.

Laban smiled. “Nothing here is made with mortar, child. Can you spin? Can you weave?”

“I can learn anything that needs hands to do it,” she said.

“A girl who can’t spin,” said Cousin Noam, shaking his head.

It made her heart sink with despair. They won’t want me, she thought.

“The girl’s a good one,” said her friend. “She learned everything very quickly. She can cook. She can learn.”

Bilhah kept wondering when the man would bring out her dowry. But after a while she realized why he had not yet done so. He wanted them to take her first for her own sake, or at least out of cousinly duty.

It soon became clear that while the master, Laban, was not averse to taking her, Cousin Noam himself was reluctant.

Until at last the cloth was unrolled and the coins exposed on the rug between them.

Cousin Noam shook his head. “This is her dowry. I’m not going to marry her! What good does this money do me?”

Bilhah saw how Laban’s gaze grew dark, his eyes more heavy-lidded. “Why is it,” he asked, “that you measure your cousin by how much of her money is yours, and I measure her by her usefulness to the camp?”

It was her friend the harness maker who answered first. “It’s because both of you are blind, not to see the beauty and goodness of this child.”

Cousin Noam whirled on him with a rebuke on his lips, but he was stopped by Lord Laban’s burst of laughter. “You are a brave man!” he said, still gasping from the laugh. “And a true friend to your friend’s child.” Laban reached down and took five coins from the pile on the cloth and offered them to the harness maker. “Her father would want you to take this, for the days of work you have lost, and for your loyalty to her.”

The harness maker took the coins, but then laid them all back down on the cloth. “I will gladly take a meal from your hospitality, my lord,” he said. “But from her dowry I will not take even the flakes of gold that cling to the cloth.”

Laban nodded again, and smiled. “We have good harness men here,” he said, “or I’d offer you work.”

“And I’d do the work gladly,” said her friend, “because your animals are so well cared-for, and for taking in the daughter of my friend.”

“Oh, I’m not taking her in,” said Laban. “She’s a free girl, though she’s under the care of my servant Noam. He will take her in, and he will guard her dowry.”

Cousin Noam nodded gravely. “She is now my daughter, and I am now her father.”

Though he was nothing like her father, Bilhah understood that his words were the covenant, and she answered alike. “Like my own father I will obey and serve you, sir,” she said. “I am your dutiful daughter now, and I put my dowry into your safekeeping.”

The cloth was rolled up again, and instead of going into the harness maker’s bag, it was tucked into the belt that cinched the loose robe around Cousin Noam’s waist.

They ate in midafternoon, and after much thanking and honoring and blessing and promising all kinds of future kindnesses, her father’s friend led the donkey away, heading back to the inn to spend a second night.

Cousin Noam introduced her to several people, warning her sternly that each adult had much to teach her as long as she was not ungrateful and served well. To each of them Bilhah bowed the way her father had always bowed to the men he worked for, and because they laughed a little she knew she was not supposed to do that; but the laughter was kind, she knew that it was not seen as a fault in her, and so she persisted. Someday someone would teach her what a free girl was supposed to do, if not to bow like a picture-tile man.

And that night she went to sleep inside a house made snug by tight walls and warmed by the bodies of four other girls, most of them younger than her.

In the morning, when she woke, Cousin Noam was gone. The dowry was too much temptation for him. It meant freedom, because with that money he could go far enough to escape the vengeance of Lord Laban.

But it meant the opposite to Bilhah, for now she, having been recognized as Noam’s “daughter,” was responsible for his debt to Laban.

She prostrated herself before him and wept the most sincere and bitter tears of her life, for now at last she truly was alone, and at the mercy of strangers.

“I know that I owe the value of my cousin’s servitude,” she said. “But I’m small and weak and have no money, either, and I don’t know how to do any of the work of this camp.”

“Your cousin Noam is a thief,” said Laban mildly. “And I don’t hold a child responsible for the debts of the man who robbed her. You are a free girl; I won’t take you as a slave to pay for a slave’s debt.”

“Then where will I go?” she said, weeping and hiccuping because truly her life was without hope now.

“You will go nowhere,” said Laban. “I will be your cousin now.”

Oh, it was a fine moment, as her heart leapt within her to hear such a gracious saying.

But within a few months, it was as if the words had never been said. She did not think that Laban ever decided not to honor his word. She supposed that he meant them at the time, but they had come too easily to his lips to last for long in his memory. Soon she was just one of the servant girls in Padan-aram, and if she got special treatment now and then, she knew it was more because she was pretty like her mother had been than because Laban remembered that she alone of the girls in her little stone house was free.

The end of my father’s life was the end of my freedom after all, she thought, then and many times afterward.

And as years went by, when the pain of Noam’s betrayal and Laban’s forgetfulness had worn away, the thing that stung her most was her own ungrateful heart. For she remembered Cousin Noam’s name, though he had robbed her and left her to take his place in servitude. But the name of Papa’s friend, the harness maker who had refused to take even the flakes of dust that clung to the cloth, his name was lost in the darkness of memory, and though twice she had dreams in which she thought she remembered it, the name always slipped away upon waking.

CHAPTER TWO

At first Bilhah was trained like any of the other girls. Learning to water the animals, to card wool, to gather dung for drying and burning, to hoe the garden and tell weeds from food, to sew, to cook, to wash whatever needed washing, and above all, to keep the distaff ever spinning in her hand.

It was weary work, and none of it drew upon her mind the way her father’s work had, with the need to learn the fine gradations of color, what was a match and what was not, and how to imagine a shape to continue a line. Nor was she called upon to remember clients’ names and all the things they asked for, or where they lived, or which shops provided the goods that were needed, and which shopkeepers were prone to try to cheat her when she came alone. Her mind was still full of all this information, which made her work here in Laban’s household seem tedious and empty.

But the other girls thought that the things she knew from Byblos were useless. They asked about the city at first, hoping for tales of marvels and wonders from the sea. At first Bilhah was shy to talk about it, because the city brought back memories that made her cry. After a few weeks, though, she ventured a few comments about how things were in Byblos—only now the other girls weren’t interested, and it wasn’t long before one of the older ones said, “You’re not in Byblos anymore, so shut up about it.”

The truth was that the things Bilhah knew from Byblos were useless here, and it wasn’t many months before she found that she could remember the streets of the city only in her dreams, and then they never led where they were supposed to, and in her dreams she could never find anything, or if she did, the wrong people were there, or they didn’t have what she needed in the dream, and more than once she woke up in tears, thinking, It’s not my city, this isn’t where I live. In the dream she was thinking it was Byblos, only changed; but when she woke, the words she found herself murmuring meant something else: that this sprawling camp in the grassy hills of Padan-aram was not her city, was not a place where she belonged at all.

And it was true. She did not belong. Oh, the tasks that took mere manual dexterity she mastered well enough. Spinning thread might drive her half mad, doing it hour after hour, but her work was as good as anyone’s after a very short time. And she could clean and sew and cook as well as the other girls her age.

But the animals were impossible. She didn’t have the feel for it, even with the small ones. She saw the other girls cuddle with lambs and frolic with kids, and watched the little boys roll and play with the dogs of the camp. But when she came near even the most docile animal, the stink offended her and made her want to shy away, and when the animal moved she leapt back instinctively.

She heard one of the old women say to another, “It’s because her father was crushed by a donkey,” and maybe there was something to that. She hadn’t been afraid of the donkey she had ridden all the way here, but that was because she was on top of it; when she was down among the animals’ feet, then it was true, their stamping and shuffling in the dirt made her uneasy. And maybe to her the smell of animals was the smell of death, because it had been so strongly in her nostrils as she breathed along with her father’s last labored breaths.

What difference did it make, though, why she didn’t like being with the animals? This was a herdkeeper’s household, and everyone had to help with animals all the time.

Everyone, that is, except Laban’s oldest daughter, Leah. But that wasn’t because she was shy of them. She’d hug a lamb like any of the servant girls, and there were a couple of dogs that everyone regarded as hers, because they ate from her hand and when she went out in the camp, they trotted along with her, sometimes running ahead, but always returning, as if she were queen and they were her guards and servants.

Leah didn’t have to help with the animals like everyone else because she was tender-eyed. In bright sunlight she squinted, even though she wore a fine black cloth over her face to fend off the worst of the dazzle. And she couldn’t see anything at all that was far off. Bilhah had noticed it almost at once, because when she first encountered Leah, she walked right up to Bilhah and peered at her closely, her face only inches away, her head moving up and down as if she could see no more than a palm-size patch of Bilhah at a time.

But Leah was not blind. Bilhah had made the mistake of calling her “the blind girl” to one of the older servant women, and to Bilhah’s shock, the woman slapped her, and not lightly, either. “The lady Leah is not blind,” the woman said harshly. “Her eyes are tender, and this causes her great danger, for she cannot see things that might be approaching from far away. But she can see well enough to know who she’s talking to, and to go wherever she wants in the camp, and to tend the garden. And she can hear words that are uttered half the camp away, including the words of stupid servant girls who call her blind, which makes her cry. And only the worst sort of person would ever make Leah cry.”

The woman’s lecture did the job—and to avoid the chance of giving offense to Leah, who could apparently hear like the gods, Bilhah didn’t mention Leah at all after that, to anyone. She also avoided her, because it was so strange to know that Leah could see her and not see her at the same time. Once, though, when Bilhah was alone out at the women’s private booth, she tied a scarf across her eyes and tried to do everything just by the feel of it. She found she made a tangle of her clothing and kept fearing that she’d step in something awful and after only a few minutes she took off the scarf and looked around gratefully and vowed never to be envious of Leah, even if she was the daughter of Lord Laban, and a lady.

Big as the camp was, however, there was no way to avoid someone forever, and on a particular day in the rainy season, almost half a year after Bilhah arrived, she was in the garden plucking beans when Leah started up another row, pulling weeds from the pepper plants.

Even though she wore her veil and was far at the other side of the field, Leah waved to her. “I know you,” she said. “You’re the mysterious cousin.”

Cousin? Not Leah’s cousin. And there was nothing mysterious about Bilhah.

“Noam used to talk about how his cousin was a great artist in colored tiles,” said Leah loudly.

Bilhah did not know what to say to this, especially with Leah shouting it over such a distance. Well, not shouting, really, but her voice was pitched so that it carried, and Bilhah was sure that she could not answer without her words being heard all over Padan-aram.

“It’s all right that you don’t want to talk about it,” said Leah. Then she rose up and walked down the row until she was parallel with Bilhah, and only a few steps away. “I can weed beside you as easily as I can weed across the field from you.”

“Yes, Lady,” said Bilhah.

“Please call me Leah.”

“I’m Bilhah.”

“I know,” said Leah. “And you’re a free girl, not a servant.”

“I can’t tell that it makes any difference,” said Bilhah. “Without money, there’s no freedom anyway.”

“God will punish Noam for what he did,” said Leah matter-of-factly. “So you don’t have to worry about that.”

“I don’t care about punishing him,” said Bilhah. “I just wish I had my papa’s money back. He didn’t save it all those years to give it to Uncle No.”

“Well, if it’s any comfort, you can be sure that Uncle No doesn’t have it anymore, either,” said Leah. “The reason he had to sell himself to my father was because he’s the worst gambler who ever lived, and what he doesn’t lose at gaming he gives to bad women.” Then Leah giggled. “I’ve never met a bad woman, so I don’t know why men give them money.”

“I saw a lot of them,” said Bilhah. “They paint their faces and call out rudely to farmers and travelers.”

“What do they say?” asked Leah.

Bilhah blushed and said nothing.

“You’re blushing,” said Leah.

“I thought you couldn’t see,” Bilhah blurted. And then, mortified, she said, “I’m sorry, Lady.”

“I can’t see very well,” said Leah. “But I know that when people blush, they hold still and sort of dip their heads in a certain way, and you did that, even though you’re plucking beans.”

“So you didn’t see me blush,” said Bilhah.

“I see more than I see, if you know what I mean,” said Leah. “Most people don’t see the things I see, because they don’t have to. And call me Leah, please.”

“Nobody calls you by name, Lady,” said Bilhah.

“I know, and that’s why I wish you would.”

“But if one of the older women hears me, she’ll slap my face, and if one of the girls hears me, she’ll tell.”

“Then call me Leah when nobody else can hear.”

“Yes, Lady.”

Leah giggled. Bilhah realized that Leah’s giggle was more about embarrassment or frustration than about amusement. So she decided not to be offended, because Leah wasn’t actually laughing at her.

“I came out here to see if I would like you,” said Leah, “and I do.”

“Thank you … Leah.”

“Because I was talking to Father and I said, If the tile-setter’s daughter can’t work with the animals, then let me have her, and he said, Be sure you like her well enough to have her with you day after day.”

Bilhah had nothing to say. The whole idea of this girl saying to her father, “Let me have her,” as if Bilhah were a puppy or a lamb—no one would have spoken of her that way in Byblos. And even here, that’s how they talked about servants, not about free women. So even though Leah remembered that Bilhah was free, she still thought of her as someone she could ask her father for.

“You don’t want to stay with me,” said Leah.

“I didn’t say anything,” said Bilhah.

“I know,” said Leah. “You caught your breath and held very still, and now your heart is beating fast and I think you’re angry with me, but I don’t know why.”

“I’m not angry, Mistress,” said Bilhah.

“I’m not your mistress,” said Leah. “You’re free.”

“But you can ask your father to let you ‘have’ me.” The words escaped before she could stop them.

Leah was quiet for a moment. “I’m sorry, I didn’t think. I meant only that I need help, and since you aren’t good with animals, you’d be the best choice to help me, since I can’t work with them either.”

“What do you need help with?” asked Bilhah.

“My eyes aren’t getting better. It hurts to read. If you could read aloud to me.”

Bilhah laughed. “I can’t read,” she said.

“But I thought you kept the counts for your father.”

“I kept them, yes,” said Bilhah. “In my head. It’s not as if we had all that many customers.”

“Well, then,” said Leah, “we’ll begin with me teaching you how to read.”

“But that’s for priests and pri

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...