- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

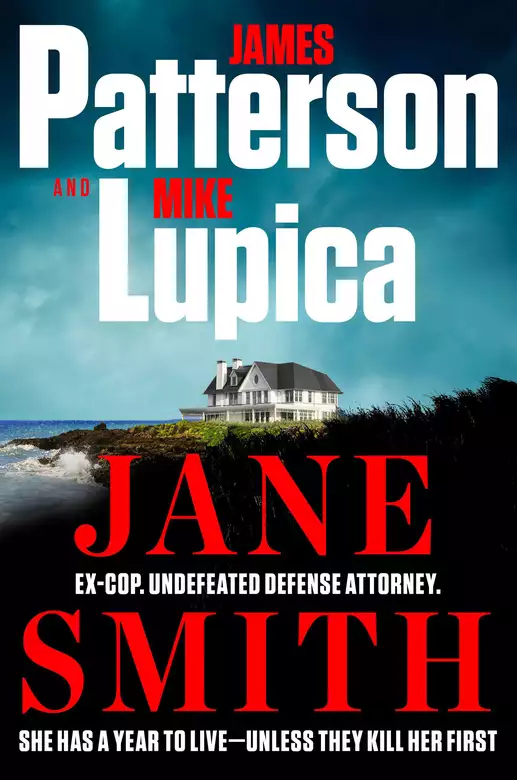

Synopsis

Criminal attorney Jane Smith, tough as nails, has received a terminal diagnosis and doesn't have much time. Is her own client trying to kill her first?

Jane Smith is an ex-NYPD beat cop, indefatigable private investigator, undefeated defense attorney.

She’s hip-deep in the murder trial of the century. Actually, her charmless client might’ve committed several murders.

She’s fallen in love with a wonderful guy. And an equally wonderful dog, a mutt.

But Jane has just fourteen months to live.

Unless she’s murdered before her expiration date.

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Jane Smith

James Patterson

“FOR THE LAST TIME,” my client says to me. “I. Did. Not. Kill. Those. People.”

He adds, “You have to believe me. I didn’t do it.”

The opposing counsel will refer to him as “the defendant.” It’s a way of putting him in a box, since opposing counsel absolutely believe he did kill all those people. The victims. The Gates family. Father. Mother. And teenage daughter. All shot in the head. Sometime in the middle of the last night of their lives. Whoever did it, and the state says my client did, had to have used a suppressor.

“Rob,” I say, “I might have mentioned this before: I. Don’t. Give. A. Shit.”

Rob is Rob Jacobson, heir to a legendary publishing house and also owner of the biggest real estate company in the Hamptons. Life was good for Rob until he ended up in jail, but that’s true for pretty much everybody, rich or poor. Guilty or innocent. I’ve defended both.

Me? I’m Jane. Jane Smith. It’s not an assumed name, even though I might be wishing it were by the end of this trial.

There was a time when I would have been trying to keep somebody like Rob Jacobson away from the needle, back when New York was still a death penalty state. Now it’s my job to help him beat a life sentence. Starting tomorrow. Suffolk County Court, Riverhead, New York. Maybe forty-five minutes from where Rob Jacobson stands accused of shooting the Gates family dead.

That’s forty-five minutes with no traffic. Good luck with that.

“I’ve told you this before,” he says. “It’s important to me that you believe me.”

No surprise there. He’s been conditioned his entire life to people telling him what he wants to hear. It’s another perk that’s come with being a Jacobson.

Until now, that is.

We are in one of the attorney rooms down the hall from the courtroom. My client and me. Long window at the other end of the room where the guard can keep an eye on us. Not for my safety, I tell myself. Rob Jacobson’s. Maybe the guard can tell from my body language that I occasionally feel the urge to strangle him.

He’s wearing his orange jumpsuit. I’m in the same dark-gray skirt and jacket I’ll be wearing tomorrow. What I think of as my sincerity suit.

“Important to you,” I say, “not to me. I need twelve people to believe you. And I’m not one of the twelve.”

“You have to know that I’m not capable of doing something like this.”

“Sure. Let’s go with that.”

“You sound sarcastic,” he says.

“No. I am sarcastic.”

This is our last pretrial meeting, one he’s asked for and that is a complete waste of time. Mine, not his. He looks for any excuse to get out of his cell at the Riverhead Correctional Facility for even an hour and has insisted on going over once more what he calls “our game plan.”

Our—I run into a lot of that.

I’ve tried to explain to him that any lawyer who allows his or her client to run the show ought to save everybody a lot of time and effort—and a boatload of the state’s money—and drive the client straight to Attica or Green Haven Correctional. But Rob Jacobson never listens. Lifelong affliction, as far as I can tell.

“Rob, you don’t just want me to believe you. You want me to like you.”

“Is there something so wrong with that?” he asks.

“This is a murder trial,” I tell him. “Not a dating app.”

Looks-wise he reminds me of George Clooney. But all good-looking guys with salt-and-pepper hair remind me of George. If I had met him several years ago and could have gotten him to stay still long enough, I might have married him.

But only if I had been between marriages at the time.

“Stop me if you’ve heard me say this before, but I was set up.”

I sigh. It’s louder than I intended. “Okay. Stop.”

“I was,” he says. “Set up. Nothing else makes sense.”

“Now, you stop me if you’ve heard this one from me before. Set up by whom? And with your DNA and fingerprints sprinkled around that house like pixie dust?”

“That’s for you to find out,” he says. “One of the reasons I hired you is because I was told you’re as good a detective as you are a lawyer. You and your guy.”

Jimmy Cunniff. Ex-NYPD, the way I’m ex-NYPD, even if I only lasted a grand total of eight months as a street cop, before lasting barely longer than that as a licensed private investigator. It was why I’d served as my own investigator for the first few years after I’d gotten my law degree. Then I’d hired Jimmy, and finally started delegating, almost as a last resort.

“Not to put too fine a point on things,” I say to him, “we’re not just good. We happen to be the best. Which is why you hired both of us.”

“And why I’m counting on you to find the real killers eventually. So people will know I’m innocent.”

I lean forward and smile at him.

“Rob? Do me a favor and never talk about the real killers ever again.”

“I’m not O.J.,” he says.

“Well, yeah, he only killed two people.”

I see his face change now. See something in his eyes that I don’t much like. But then I don’t much like him. Something else I run into a lot.

He slowly regains his composure. And the rich-guy certainty that this is all some kind of big mistake. “Sometimes I wonder whose side you’re on.”

“Yours.”

“So despite how much you like giving me a hard time, you do believe I’m telling you the truth.”

“Who said anything about the truth?” I ask.

Two

GREGG McCALL, NASSAU COUNTY district attorney, is waiting for me outside the courthouse.

Rob Jacobson has been taken back to the jail and I’m finally on my way back to my little saltbox house in Amagansett, east of East Hampton, maybe twenty miles from Montauk and land’s end.

A tourist one night wandered into the tavern Jimmy Cunniff owns down at the end of Main Street in Sag Harbor, where Jimmy says it’s been, in one form or another, practically since the town was a whaling port. The visitor asked what came after Montauk. He was talking to the bartender, but I happened to be on the stool next to his.

“Portugal,” I said.

But now the trip home is going to have to wait because of McCall, six foot eight, former Columbia basketball player, divorced, handsome, extremely eligible by all accounts. And an honest-to-God public servant. I’ve always had kind of a thing for him, even when he was still married, and even though my sport at Boston College was ice hockey. Even with his decided size advantage, I figure we could make a mixed relationship like that work, with counseling.

McCall has made the drive out here from his home in Garden City, which even on a weekday can feel like a trip to Kansas if you’re heading east on the Long Island Expressway.

“Are you here to give me free legal advice?” I ask. “Because I’ll take whatever you got at this point, McCall.”

He smiles. It only makes him better looking.

Down, girl.

“I want to hire you,” he says.

“Oh, no.” I smile back at him. “Did you shoot somebody?”

He sits down on the courthouse steps and motions for me to join him. Just the two of us out here. Tomorrow will be different. That’s when the circus comes to town.

“I want to hire you and Jimmy, even though I can’t officially say that I’m hiring you,” he says. “And even though I’m aware that you’re kind of busy right now.”

“I’d only be too busy if I had a life,” I say.

“You don’t have one? You’re great at what you do. And if I can make another observation without getting MeToo’ed, you happen to be great looking.”

Down, girl.

“I keep trying to have one. A life. But somehow it never seems to take.” I don’t even pause before asking, “Are you going to now tell me what you want to hire me for even though you can’t technically hire me, or should we order Uber Eats?”

“You get right to it, don’t you?” McCall asks.

“Unless this is a billable hour. In which case, take as much time as you need.”

He crosses amazingly long legs out in front of him. I notice he’s wearing scuffed old loafers. Somehow they make me like him even more. I’ve never gotten the sense that he’s trying too hard, even when I’ve watched him killing it a few times on Court TV.

“Remember the three people who got shot in Garden City?” he asks. “Six months before Jacobson is accused of wiping out the Gates family.”

“I do. Brutal.”

Three senseless deaths that time, too. The Carson family. Father, mother, daughter, a sophomore cheerleader at Garden City High. I don’t know why I remember the cheerleader piece. But it’s stayed with me. A robbery gone wrong. Gone bad and gone tragically wrong.

“Well, you probably also know that the father’s mother never let it go until she finally passed,” he says, “even though there was never an arrest or even a suspect worth a shit.”

“I remember Grandma,” I say. “There was a time when she was on TV so much I kept waiting for her to start selling steak knives.”

McCall grins. “Well, it turns out Grandma was right.”

“She kept saying it wasn’t random, that her son’s family had been targeted, even though she wouldn’t come out and say why. She finally told me why but said that if I went public with it, she’d sue me all the way back to the Ivy League.”

“But you’re going to tell me.”

“Her son gambled. Frequently and badly, as it turns out.”

“And not with DraftKings, I take it.”

“With Bobby Salvatore, who is still running the biggest book in this part of the world.”

“Jimmy’s mentioned him a few times in the past. Bad man, right?”

“Very.”

“And you guys missed this?”

“Why do you think I’m here?”

“But upstanding district attorneys like yourself aren’t allowed to hire people like Jimmy and me to run side investigations.”

“We’re not. But I promised Grandma,” he says. “And there’s an exception I believe would cover it.”

“The case was never closed, I take it.”

“But we’d gotten nothing new in all this time until a guy in another investigation dropped Salvatore’s name on us.”

“And here you are.”

“Here I am.”

“I don’t mean to be coarse, McCall, but I gotta ask: who pays?”

“Don’t worry about it,” he says.

“I’m a worrier.”

“Grandma liked to plan ahead,” he says. “She was ready to go when we found out about the Salvatore connection. When I took it to her, she said, ‘I told you so,’ and wrote a check. She told me that she was willing to pay whatever it took to find out who took her family.”

“This sounds like your crusade, not mine.”

“Come on, think of the fun,” Gregg McCall says. “While you’re trying to get your guy off here, you can help me put somebody else away.”

I know all about McCall by now. He’s more than just a kick-ass prosecutor. He’s also tough and honest. Didn’t even go to Columbia on an athletic scholarship. Earned himself one for academics. Could have gone to a big basketball school. His parents were set on him being Ivy League. Worked his way to pay for the rest of college. The opposite of the golden boy I’m currently representing, all in all.

“I know we’re supposed to be on opposing sides,” McCall says. “But if I can make an exception…”

I finish his thought. “So can I.”

“I’m asking you to help me do something we should have done at the time. Find the truth.”

“You ought to know that my client just now asked me if I thought he was telling the truth. I told him that I wasn’t interested in the truth.” I shrug. “But I lied.”

“If you agree to do this, we’ll kind of be strange bedfellows.”

“You wish,” I say.

Actually, I wish.

“I know asking you to take on something extra right now is crazy,” he says.

“Kind of my thing.”

Three

ON MY WAY HOME, I call Jimmy Cunniff at the tavern. He used to get drunk there in summers when he’d get a couple of days off and need to get out of the city, day-trip to the beach and party at night. Now he owns the business, but not the building, though his landlord is not just an old friend but also someone, in Jimmy’s words, who’s not rent-gouging scum.

A Hamptons rarity, if you must know.

Jimmy’s not just an ex-cop, having been booted out of the NYPD for what he will maintain until Jesus comes back was a righteous shooting, and killing, of a drug dealer named Angel Reyes. He’s also a former Golden Gloves boxer and, back in the day, someone who had short stories published in long-gone literary magazines. The beer people should have put Jimmy out there as the most interesting man in the world.

He’s also my best friend.

I tell him about Gregg McCall’s visit, and his offer, and him telling me we can name our own price, within reason, because Grandma is paying.

“You think we can handle two at once?” Jimmy asks.

“We’ve done it before.”

“Not like with these two,” he says, and I know he’s right about that.

“Two triple homicides,” Jimmy Cunniff says. “But not twice the fun.”

“Who knows, maybe solving one will show us how to solve the other. Maybe we’ll even slog our way to the truth. Look at it that way.”

“I don’t know why you even had to ask if I was on board,” Jimmy says. “You knew I’d be in as soon as you were. And you were in as soon as McCall asked you to be.”

“Kind of.”

“Stop here and we’ll celebrate,” he says.

I tell Jimmy I’ll take a rain check. I have to go straight home; I need to train.

“Wait, you’re still fixed on doing that crazy biathlon, even now?”

“I just informed Mr. McCall that crazy is kind of my thing,” I say.

“Mine, too.”

“There’s that.”

“Are you doing this thing for McCall because you want to or because the hunky DA is the one who asked you to?”

“What is this, a grand jury?”

“Gonna take that as a yes on the hunk.”

“Hard no, actually,” I say. “I couldn’t do that to him.”

“Do what?”

“Me,” I say.

There was a little slowdown at the light in Wainscott, but now Route 27 is wide-open as I make my way east.

“For one thing,” I tell Jimmy, “Gregg McCall seems so happy.”

“Wait,” Jimmy says. “Both your ex-husbands are happy.”

“Now they are.”

Four

MY TWO-BEDROOM SALTBOX is at the end of a cul-de-sac past the train tracks for the Long Island Railroad. North side of the highway, as we like to say Out Here. The less glamorous side, especially as close to the trains as I am.

My neighbors are mostly year-rounders. Fine with me. Summer People make me want to run back to my apartment in the West Village and hide out there until fall.

There is still enough light when I’ve changed into my Mets sweatshirt, the late-spring temperature down in the fifties tonight. I put on my running shoes, grab my air rifle, and get back into the car to head a few miles north and east of my house to the area known as the Springs. My favorite hiking trail runs through a rural area by Gardiners Bay.

Competing in a no-snow biathlon is the goal of my endless training. Trail running. Shooting. More running. More shooting. A perfect event for a loner like me, and one who prides herself on being a good shot. My dad taught me. He’s the one who started calling me Calamity Jane when he saw what I could do at the range.

Little did he know that carrying a gun would one day become a necessary part of my job. Just not in court. Though sometimes I wish.

I park my Prius Prime in a small, secluded lot near Three Mile Harbor and start jogging deep into the woods. I’ve placed small targets on trees maybe half a mile apart.

Fancy people don’t go to this remote corner of the Hamptons, maybe because they can’t find a party, or a photographer. The sound of the air rifle being fired won’t scare the decent people out here, who don’t hike or jog in the early evening. If somebody does make a call, by now just about all the local cops know it’s me. Calamity Jane.

I use the stopwatch on my phone to log my times. I’m determined to enter the late-summer biathlon in Pennsylvania, an event Jimmy has sworn only I have ever heard about. Or care about. He asked why I didn’t go for the real biathlon.

“If you ever see me on skis, find my real gun and shoot me with it.”

I know I’m only competing against myself. But I’ve been a jock my whole life, from age ten when I beat all the boys and won Long Island’s NFL Punt, Pass, and Kick contest, telling my dad I was going to be the first girl ever to quarterback the Jets. I remember him grinning and saying, “Honey, we’ve had plenty of those on the Jets since Joe Namath was our QB.”

Later I was Hockey East Rookie of the Year at BC. That was also where I really learned how to fight. And haven’t stopped since. Fighting for rich clients, not-so-rich ones, fighting when I’m doing pro bono work back in the city for victims who deserve a chance. And deserve being repped by somebody like me. Fighting with prosecutors, judges, even the cops sometimes, as much as I generally love cops, maybe because of an ex-cop like Jimmy Cunniff.

Occasionally fighting with two husbands.

Makes no difference to me.

You want to have a fight?

Let’s drop the gloves and do this.

I’m feeling it even more than usual tonight, pushing myself, hitting my targets like a champion. I stop at the end of the trail, kneel, empty the gun one final time. Twelve hundred BBs fired in all.

But I’m not done. Not yet. Still feeling it. Let’s do this. I reload. Hit all the targets on the way back, sorry I've run out of light. And BBs. What's the old line? Rage against the dying of the light? I wasn't much of a poet, but my father, Jack, the Marine and career bartender, liked Dylan Thomas. Maybe because of the way the guy could drink. My mother, Mary, who spent so much of her marriage waiting for my father to come from the bar, having long ago buried her dreams of being a writer, had died of ovarian cancer when I was ten. I’d always thought I had gotten my humanity from her, my sense of fairness, of making things right. It was different with my father the Marine, who always taught me that if you weren't the one on the attack, the other guy was. His own definition of humanity, just with much harder edges. He lasted longer than our mom did, until he dropped dead of a heart attack one night on a barroom floor.

It’s dark by the time I get back to the car. I’m thinking about having one cold one with Jimmy. But then I think about making the half-hour drive over to the bar in Sag Harbor and back, and how I really do need a good night’s sleep, knowing I’m going to be a little busy in the morning, even before I head to court.

I drink my last bottle of water, get behind the wheel, toss the rifle onto the back seat, knowing my real gun, the Glock, is locked safely in the glove compartment. I have a second one at home. A girl can’t have too many.

I feel like I used to feel in college, the night before a big game. I think about what the room will look like tomorrow. What it will feel like. Where Rob Jacobson will be and where I’ll be and where the jury will be.

I’ve got my opening statement committed to memory. Even so, I pull up the copy stored on my phone. I slide the seat back, lean back, begin to read it over again, keep reading until I feel my eyes starting to close.

When I wake up, it’s morning.

Six

TODAY’S APPOINTMENT IS SUPPOSED to be strictly routine, the follow-up Sam, being Sam, has always mandated to review test results after my annual physical. I keep telling her that the only reason she makes me come back is because she misses me.

“How are Rusty and Dusty?” I ask when I sit down.

Rusty and Dusty aren’t the labradoodles’ names. Just what I’ve always called them.

No reaction. “I got your test results back.”

“You don’t have to tell me,” I say. “I’m in better shape than Wonder Woman. The new hot one.”

She opens the folder in front of her and spreads out x-rays and lab reports. Sam had finally taken some pictures and done her tests because of what I had originally described to her as a persistent pain in the neck. And a bump back there that I hadn’t noticed until a couple of weeks ago. The one she biopsied.

I feel the small, dark, cold place inside me begin to grow.

Then she starts to talk. And I wish, for the life of me, I could process, even hear, everything she is saying.

But I don’t hear very much after “brain and neck cancer.”

She pauses.

“It’s further along than I’d prefer.”

“Same. I thought you said I just pulled something working with my hand weights.”

“You pulled a bad card, Jane, is what you did,” she says. “I can’t lie to you.”

“Go ahead and lie a little. I won’t stop you.”

My next words sound monumentally dumb the moment they are out of my mouth.

“This can’t happen today.”

“There’s never a good time, or a good way, to give someone news like this. Especially to someone you love.”

She asks if I want to see the pictures. I tell her I’ll save them for the scrapbook.

I try to smile. Put up a false front. Be a tough guy.

Be Jane.

Be me.

She’s now talking about squamous cells that have spread into the lymph nodes.

“When I was a kid, I thought they were limp nodes,” I say. I flop my wrist in a limp way. “I think I’d rather have some of them.”

No reaction.

“Come on. That’s funny.”

“None of this is funny,” Sam Wylie says. “And we both know it.”

“What am I supposed to do? Cry?”

“If you want to.”

“I don’t,” I say. “Cry, I mean.”

“I do,” Sam Wylie says.

She’s talking slowly, patiently, but all I hear are the words running together, about che. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...