- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

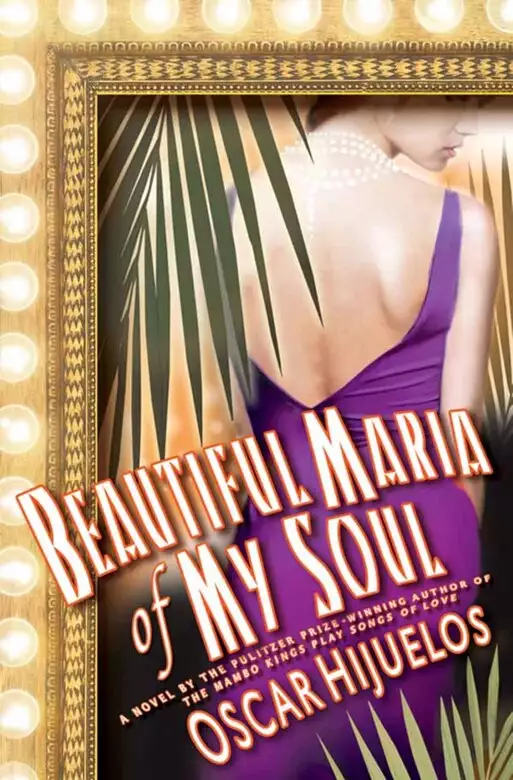

In this mesmerizing sequel to a Pulitzer Prize winning novel, The Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love, the "heart-stealing heroine" (Amy Tan) and muse of Cuban musician Nestor Castillo takes readers on the journey of a lifetime with this story of reinvention, romance, and revolution.

In Beautiful María of My Soul, Oscar Hijuelos returns to the passionate tale he began twenty years ago in The Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love.

María is the great Cuban beauty who stole musician Nestor Castillo's heart and broke it, inspiring him to write the Mambo Kings' biggest hit, "Beautiful María of My Soul.'" Now in her sixties and living as an exile in Miami, María remains a beauty, still capable of turning heads. But while she left Cuba decades ago, she has never forgotten Nestor. As she thinks back to her days—and nights—in Havana, an entirely new perspective on the Mambo Kings story unfolds. Beautiful María of My Soul is a stunning act of reinvention, and another contemporary classic from an extraordinarily talented writer.

"Savor the mysterious power of a master's pentimento." —Los Angeles Times

"It takes a lot of nerve and skill to pull off something as rich as Beautiful MarÍa of My Soul, but pull it off Hijuelos does." —Cleveland Plain Dealer

"I fell instantly in love with the glorious soul of Beautiful María of My Soul. Hijuelos has created and brought to life two beloved characters, a heart-stealing heroine and Havana during an epoch of changing fate." —Amy Tan, bestselling author of The Joy Luck Club

In Beautiful María of My Soul, Oscar Hijuelos returns to the passionate tale he began twenty years ago in The Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love.

María is the great Cuban beauty who stole musician Nestor Castillo's heart and broke it, inspiring him to write the Mambo Kings' biggest hit, "Beautiful María of My Soul.'" Now in her sixties and living as an exile in Miami, María remains a beauty, still capable of turning heads. But while she left Cuba decades ago, she has never forgotten Nestor. As she thinks back to her days—and nights—in Havana, an entirely new perspective on the Mambo Kings story unfolds. Beautiful María of My Soul is a stunning act of reinvention, and another contemporary classic from an extraordinarily talented writer.

"Savor the mysterious power of a master's pentimento." —Los Angeles Times

"It takes a lot of nerve and skill to pull off something as rich as Beautiful MarÍa of My Soul, but pull it off Hijuelos does." —Cleveland Plain Dealer

"I fell instantly in love with the glorious soul of Beautiful María of My Soul. Hijuelos has created and brought to life two beloved characters, a heart-stealing heroine and Havana during an epoch of changing fate." —Amy Tan, bestselling author of The Joy Luck Club

Release date: June 1, 2010

Publisher: Hachette Books

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

Beautiful María of My Soul

Oscar Hijuelos

In an 1889 engraving for the frontispiece of London Street Arabs, Dorothy Tennant is posed in profile, her jewelry-laden left hand just grazing her plumpish chin. It captured her well. She had a high, gracefully rising forehead and a great head of curling, perhaps graying hair, pensive brows, a nose that was prominent but not oppressive, thin and pursing lips, delicate and fleshy ears, and eyes that were dark and alert, her features bringing to mind a classical portrait of a Roman or Greek lady.

Tennant was a woman of wealth and high social bearing who lived in a Regency mansion on Richmond Terrace, off Whitehall, in London. This rendering of her was made but a year before her marriage to Henry Morton Stanley, explorer and “Napoleon” of journalists, whose roots had been so humble that his childhood experiences and poor upbringing in Wales would have been an abstraction to her, for her own experience had never included want or deprivation. That she, the artistic and lively pearl of London society, had become involved and happily betrothed to Stanley after a well-known period of difficulties between them was one of the great mysteries of Victorian courtships.

Like just about everyone else in England, she had been caught up in the national frenzy over Africa, having followed with rapt interest the careers of Livingstone, Baker, Cameron, Speke, and Burton, among others, whose exploits were reported in all the newspapers and commemorated in books. She had been in her adolescence when the first of these explorations began, but by 1871 the greatest of all such explorers, Henry Morton Stanley, had emerged. He first became known for his search to find the Scottish missionary David Livingstone. His later activities in the region, principally in the Congo, where he had spent many years leading other expeditions, often under impossible conditions, had only increased his stature as a heroic figure in the public mind. Stanley had been so successful in opening the equatorial center of the continent that he had become one of the most famous men in England. (“Before Stanley there was no Africa,” Tennant would later write.)

Despite Stanley’s mercurial personality and the burden of his many maladies, such as chronic gastritis and numerous bouts of malaria—“the Africa in me,” he called it—their marriage had flourished, and they became one of the most famous couples in England. Tennant’s haughty circle of friends intersected with Stanley’s colleagues and acquaintances—professional relationships, for the most part. But now and then there surfaced the occasional true friendship, such as the one he had with the American writer Samuel L. Clemens, or Mark Twain, as he was most famously called.

Tennant first met Clemens at a dinner in New York City while accompanying Stanley on a lecture tour of the United States. It was an introduction that culminated, in the month of January, 1891, with an invitation to visit Clemens at his Hartford home on Farmington Avenue, where Dorothy and her mother, Gertrude, spent a most diverting few days with him and his family (at the time, Stanley was away, lecturing in Trenton and other cities in New Jersey). Thereafter, over the next decade and a half, she and Stanley saw them on various occasions, principally in London, where the Clemenses lived in the mid-1890s, then later, at the turn of the century, when they had taken up residence in England once again.

In those years, paying socials calls to the Tennant mansion on Richmond Terrace, Clemens passed many hours in their company, giving impromptu recitations for their friends at dinners, shooting billiards, and occasionally withdrawing into her studio, a canvas- and prop-cluttered room known as the birdcage, to sit as a portrait subject for Dorothy, who, in her day, was greatly admired as an artist.

It had been her wish to present a portrait of Clemens to the National Portrait Gallery, as she had done in 1893 with a commendable rendering of her explorer husband, whom she had captured in all his splendor. Dolly had made dozens of studies of Stanley during their early courtship and dozens more in the years after their marriage—each session an immersion, she felt, into the spirit of her subject, for once he had become trusting of her, fruitful conversations ensued, and his tortured soul poured naturally forth.

The same kind of exchanges took place with Clemens, from whom Dolly had learned details about his private life—his joyfulness and pride in his family; the pain of certain devastating events that made his later years difficult. She had spent perhaps twenty hours sketching him. He had been an occasionally distracted subject, fidgeting with a cigar, getting up at any moment to stretch his stiff limbs, often staring out the window to look at the Irish perennials in her garden and sometimes losing patience with the whole idea of sitting still. Yet when she got him to talking about the things that made him happy, mainly his youth in Hannibal—the perpetually springlike wonderland from which his most memorable characters flowed—time stopped, his discomforts left him, and a serenity came over his famously leonine countenance.

* * *

• “As you surely know, Dolly, I have always been fond of Stanley. Not that he’s the easiest person to understand, but he kind of grows on a body. His convictions, his work ethic, his knowledge of many things—these qualities appeal to me, even if I do not always agree with him. He’s not the easiest person to get along with, by any stretch, which, by the way, I do not mind. And he is one of the moodiest people I have ever known, besides myself, and has been so ever since I first knew him. Our saving grace is that we have similar temperaments and can disagree or feel gloomy or cantankerous around each other without standing on ceremony; we are just that way.”

He had paused then to relight a cigar, drawing from his vest pocket a match, which he struck against the heel of his shoe.

“Somehow, ours has been a friendship that’s lasted. I cannot say that he is as close to me as my best friends in the States, but I hold him in considerable esteem just the same. The fact is we go back together to simpler times, an enviable thing. As much as he has changed over the years, he is not so different from the young man I met years ago, on a riverboat—you know of this, do you not?”

“He told me once that you met long ago.”

“Indeed we did. It was a friendship that commenced by chance—on the boiler deck of a steamboat heading upriver, between New Orleans and St. Louis…in the autumn of 1860, just before the Civil War, during my days as a Mississippi River pilot.”

A plume of bluish smoke.

“Stanley was traveling in the company of his adoptive American father, a merchant trader who plied the Mississippi port towns. He was Stanley’s mentor in New Orleans and a great influence on his manner of dress and grooming, and he did much, as I remember, to advance his son’s education, which by my lights was already considerable. Stanley was one of the better-read young men on that river. Of course I already knew some bookish types; Horace Bixby, a fellow pilot, got me to reading William Shakespeare, and occasionally I’d meet some traveling professor or any number of journalists with whom I could sometimes talk about literature. But Stanley, in those days, with his good common-school English education—one that he was modest about—was quite a cut above the average Mississippi traveler. And he seemed the most guileless and unassuming fellow one could ever encounter, to boot.”

He puffed on his cigar again, and even as he was speaking, conjured, in his mind, the sight of drowsy still waters at dusk, campfires along the Mississippi River dotting the shore with light, the stars beginning to rise.

“He always had a book in hand and seemed anxious to learn about the world: I found myself beguiled by him, and I was touched that he seemed to be in need of a friend. We were both young men—I was twenty-five or so, and I believe Stanley was then about nineteen, the same age as my dear recently deceased younger brother, also named Henry. I suppose I was ready and willing to befriend Stanley for that reason alone, though who knows how or why chance happens to place a person in one’s path. Whatever the mysterious cause, our friendship blossomed and eventually led to a quite interesting run of years. I am surprised that he has not told you more about our beginnings.”

* * *

• She sits down to write a letter in the parlor of her mansion, the interior unchanged from the day Stanley had died, three years before, at six in the morning, just as Big Ben was ringing in that hour from a distance. In its rooms many of Stanley’s possessions and keepsakes remain where she had put them; in the hallways, framed photographs of Stanley on safari, Stanley in Zanzibar with his native porters, Stanley poised on a cliff in the rainbow mists of Victoria Falls. A bookcase bears a multitude of first editions and translations of his African memoirs. Atop the numerous tables and travertine pedestals are a variety of ornate freedom caskets from cities like Dundee, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Swansea, and Manchester, each honoring Stanley for one or the other of his African exploits. Here and there, hanging on a wall, are plaques that Stanley had particularly liked. One of them, harking back to 1872, when he had become famous for finding Livingstone in the wilds of Africa, reads:

A COMMON COUNCIL

HOLDEN IN THE CHAMBER OF GUILDHALL, OF THE CITY OF LONDON

ON THURSDAY, THE 21ST DAY OF NOVEMBER, 1872,

RESOLVED UNANIMOUSLY

THAT THIS COURT DESIRES TO EXPRESS ITS GREAT APPRECIATION OF THE EMINENT SERVICES RENDERED BY

MR. HENRY MORTON STANLEY

TO THE CAUSE OF SCIENCE AND HUMANITY BY HIS PERSISTENT AND SUCCESSFUL ENDEAVORS TO DISCOVER AND RELIEVE THAT ZEALOUS AND PERSEVERING

MISSIONARY AND AFRICAN TRAVELLER,

DR. DAVID LIVINGSTONE,

THE UNCERTAINTY OF WHOSE FATE HAD CAUSED SUCH DEEP ANXIETY, NOT ONLY TO HER MAJESTY’S SUBJECTS, BUT TO THE WHOLE CIVILISED WORLD.

There are framed maps of Africa and bronze busts of Stanley lining the hallways and several Minton biscuit figurines of Stanley—the kind that were sold for years in the tourist shops of Piccadilly—set out on a parlor table. On a desk in Lady Stanley’s own study, just down the hall from her painting studio, sit her commonplace books and a manuscript of her own writings—the fragments of a memoir (never to be completed) called My Life with Henry Morton Stanley—alongside a plaster cast of Stanley’s left hand, which she keeps for good luck. But there is also much more about Stanley—diplomas, royal decrees, gold medals (the Order of Leopold and the Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath from the late queen; the Grand Cordon of the Imperial Order of Medijdieh from the khedive of Egypt)—to come upon in that house. There are also many other keepsakes—old compasses, sextants, and other instruments as well as various native African artifacts, such as Zulu fly whisks, spearheads, and phallic oddities brought back by Stanley after his journeys—on display in a curio cabinet.

As she writes, his presence is inescapable. Even as she is about to remarry, in a few weeks, Lady Stanley has never gotten around to removing a thing from Stanley’s private bedroom—they had sometimes slept apart. His wardrobe closet still contains the Savile Row suits he favored, along with his shirts, his lace bow ties, his vests, suspenders, stockings, his walking sticks, and many pairs of his distinctively smallish-size shoes. Even his bedside table has remained as it was the morning he left her—a pair of wire-rimmed spectacles sitting atop the pages of a Bible, opened to the chapters of Genesis. Nor has she touched the mantel clock with Ottoman numerals, except to rewind it nightly; nor has she removed from that chamber the other books he had taken much comfort in: Gladstone’s Gleanings of Past Years, a volume of autobiographical essays that Stanley admired despite his personal dislike of the man (“I detect the churchgoing, God-fearing, conscientious Christian in almost every paragraph,” he had written); the histories of Thucydides; and two novels, David Copperfield by Charles Dickens (“That boy was me, in my youth” he once said) and another by his old friend Mark Twain, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn—the very copy Stanley had carried with him on his final expedition to Africa.

And along with the framed photographs he had asked to be placed near him as he had lain in his bed, beside those of Denzil, Queen Victoria, and Livingstone, there are several oil studies made by Lady Stanley in earlier days: Stanley sitting on the lawn of their country estate in Surrey; a portrait of Samuel Clemens that Dolly had commenced some years before in her studio.

May 11, 1907

2 Richmond Terrace, Whitehall, London

Dearest Sam,

I have been going through Henry’s many papers and notebooks in my attempt to fill out his history. In his study, he kept several large cabinets of facsimiles of letters, old manuscripts, and notebooks. He was a hoarder of all things pertaining to himself, perhaps for the sake of the historical record, and so, as you may well imagine, there has been quite a bit to consider. Lately, I have made it my habit to spend a part of my days searching for materials pertinent to the story of his life—no easy task, given their volume. It is a labor I have conducted in slow but steady measures.

In any event, I have come across a manuscript that I had never seen before. It is a manuscript I believe Henry had commenced shortly after we had visited New Orleans in the autumn of 1890, while on tour for dear Major Pond, when Henry’s memories of his life there, after an absence of thirty years, had been freshly reawakened. Since much of it was written out on stationery from hotel and steamship lines, with which I am familiar, having accompanied Stanley on his tours of the States and Australia in 1891 and 1892, I date its composition to that time. At first, I had thought the manuscript a preliminary version of the chapters regarding his first years in his adopted country, which Henry would later refine. But as I read on I was surprised to see how much it diverged from what he later left as the “official” version, for these pages contain an untold story. And that story has presented me, as the amateur compiler of his life, with a very great dilemma.

And here it is: In the completed sections of the autobiography, which he approved for publication, he plainly states that Henry Hope Stanley, the merchant trader from New Orleans whom he considered his second father, had vanished during a journey to Cuba, where he had a business: “He died in 1861. I did not learn this until long afterward,” is how he summarized it. Yet the “cabinet” manuscript, if I may call it so, seems to be an elaborate explanation of Henry’s search for his father in Cuba, a journey he claims, in these pages, to have made in the days of late March and early April of 1861, with you.

Samuel, as delighted as I had been over this unexpected revelation, you must imagine the state of perplexity it put me in. For in this manuscript contradicts what Henry once told me about his experiences in Cuba, which he claimed to have visited only once, in 1865; he said that he made that journey to see his adoptive father’s grave for himself, the elder Mr. Stanley having been buried “in some churchyard near Havana.” And the only time he had mentioned you in relation to his early days in America—in fact, while we were strolling down the Vieux Carré of New Orleans during our 1891 journey there—he referred to your chance meeting “along some stretch of the Mississippi,” aboard a riverboat, years ago. But he never elaborated about your early friendship, nor did he begin to hint at the extent to which he had, in fact, privately written about you. Since it was obviously Henry’s wish to exclude this narrative from his official story, I am assuming that he had his reasons, upon which I hope you will shed some light. I have taken the liberty of sending you a typescript version (Henry’s original, often written in a post-malarial state, suffers from stains and an addled penmanship). Once you have read it, I hope you can answer this question: Was it so, Samuel?

Copyright © 2015 by the Estate of Oscar Hijuelos

Over forty years before, when Nestor Castillo’s future love, one María García y Cifuentes, left her beloved valle in the far west of Cuba, she could have gone to the provincial capital of Pinar del Río, where her prospects for finding work might be as good—or bad—as in any place; but because the truck driver who’d picked her up one late morning, his gargoyle face hidden under the lowered brim of a lacquered cane hat, wasn’t going that way and because she’d heard so many things—both wonderful and sad—about Havana, María decided to accompany him, that cab stinking to high heaven from the animals in the back and from the thousands of hours he must have driven that truck with its loud diesel engine and manure-stained floor without a proper cleaning. He couldn’t have been more simpático, and at first he seemed to take pains not to stare at her glorious figure, though he couldn’t help but smile at the way her youthful beauty certainly cheered things up. Okay, he was missing half his teeth, looked like he swallowed shadows when he opened his mouth, and had a bulbous, knobbed face, the sort of ugly man, somewhere in his forties or fifties—she couldn’t tell—who could never have been good looking, even as a boy. Once he got around to tipping up his brim, however, she could see that his eyes were spilling over with kindness, and despite his filthy fingernails she liked him for the thin crucifix he wore around his neck—a sure sign, in her opinion, that he had to be a good fellow—un hombre decente.

Heading northeast along dirt roads, the Cuban countryside with its stretches of farms and pastures, dense forests and flatlands gradually rising, they brought up clouds of red dust: along some tracks it was so hard to breathe that María had to cover her face with a kerchief. Still, to be racing along at such bewildering speeds, of some twenty or thirty miles an hour, overwhelmed her. She’d never even ridden in a truck before, let alone anything faster than a horse and carriage, and the thrill of traveling so quickly for the first time in her life seemed worth the queasiness in her stomach, it was so exciting and frightening at the same time. Naturally, they got to talking.

“So, why you wanna go to Havana?” the fellow—his name was Sixto—asked her. “You got some problems at home?”

“No.” She shook her head.

“What are you gonna do there, anyway? You know anyone?”

“I might have some cousins there, from my mamá’s side of the family”—she made a sign of the cross in her late mother’s memory. “But I don’t know. I think they live in a place called Los Humos. Have you heard of it?”

“Los Humos?” He considered the matter. “Nope, but then there are so many hole-in-the-wall neighborhoods in that city. I’m sure there’ll be somebody to show you how to find it.” Then, picking at a tooth with his pinkie: “You have any work? A job?”

“No, señor—not yet.”

“What are you going to do, then?”

She shrugged.

“I know how to sew,” she told him. “And how to roll tobacco—my papito taught me.”

He nodded, scratched his chin. She was looking at herself in the rearview mirror, off which dangled a rosary. As she did, he couldn’t resist asking her, “Well, how old are you anyway, mi vida?”

“Seventeen.”

“Seventeen! And you have nobody there?” He shook his head. “You better be careful. That’s a rough place, if you don’t know anyone.”

That worried her; travelers coming through her valle sometimes called it a city of liars and criminals, of people who take advantage. Still, she preferred to think of what her papito once told her about Havana, where he’d lived for a time back in the 1920s when he was a traveling musician. Claimed it was as beautiful as any town he’d ever seen, with lovely parks and ornate stone buildings that would make her eyes pop out of her head. He would have stayed there if anybody had cared about the kind of country music his trio played—performing in those sidewalk cafés and for the tourists in the hotels was hard enough, but once that terrible thing happened—not just when sugar prices collapsed, but when the depression came along and not even the American tourists showed up as much as they used to—there had been no point to his staying there. And so it was back to the guajiro’s life for him.

That epoch of unfulfilled ambitions had made her papito sad and sometimes a little careless in his treatment of his family, even his lovely daughter, María, on whom, as the years had passed, he sometimes took out the shortcomings of his youth. That’s why, whenever that driver Sixto abruptly reached over to crank the hand clutch forward, or swatted at a pesty fly buzzing the air, she’d flinch, as if she half expected him to slap her for no reason. He hardly noticed, however, no more than her papito did in the days of her own melancholy.

“But I heard it’s a nice city,” she told Sixto.

“Coño, sí, if you have a good place to live and a good job, but—” And he waved the thought off. “Ah, I’m sure you’ll be all right. In fact,” he went on, smiling, “I can help you maybe, huh?”

He scratched his chin, smiled again.

“How so?”

“I’m taking these pigs over to this slaughterhouse, it’s run by a family called the Gallegos, and I’m friendly enough with the son that he might agree to meet you…”

And so it went: once Sixto had dropped off the pigs, he could bring her into their office and then who knew what might happen. She had told him, after all, that she’d grown up in the countryside, and what girl from the countryside didn’t know about skinning animals, and all the rest? But when María made a face, not managing as much as a smile the way she had over just about everything else he said, he suggested that maybe she’d find a job in the front office doing whatever people in those offices do.

“Do you know how to read and write?”

The question embarrassed her.

“Only a few words,” she finally told him. “I can write my name, though.”

Seeing that he had made her uncomfortable, he rapped her on the knee and said, “Well, don’t feel bad, I can barely read and write myself. But whatever you do, don’t worry—your new friend Sixto will help you out, I promise you that!”

She never became nervous riding with him, even when they had passed those stretches of the road where the workers stopped their labors in the fields to wave their hats at them, after which they didn’t see a soul for miles, just acres of tobacco or sugarcane going on forever into the distance. It would have been so easy for him to pull over and take advantage of her; fortunately this Sixto wasn’t that sort, even if María had spotted him glancing at her figure when he thought she wasn’t looking. Bueno, what was she to do if even the plainest and most tattered of dresses still showed her off?

Thank goodness that Sixto remained a considerate fellow. A few times he pulled over to a roadside stand so that she could have a tacita of coffee and a sweet honey-drenched bun, which he paid for, and when she used the outhouse, he made a point of getting lost. Once when they were finally on the Central Highway, which stretched from one end of the island to the other, he just had to stop at one of the Standard Oil gas stations along the way, to buy some cigarettes for himself and to let that lovely guajira see one of their sparkling clean modern toilets. He even put a nickel into a vending machine to buy her a bottle of Canada Dry ginger ale, and when she belched delicately from all the burbujas—the bubbles—Sixto couldn’t help but slap his legs as if it was the funniest thing he had ever seen.

He was so nice that she almost became fond of him despite his ugliness, fond of him in the way beautiful women, even at so young an age, do of plain and unattractive—hideous—men, as if taking pity on an injured dog. As they started their approach towards one of the coastal roads—that air so wonderful with the scent of the gulf sea—and he suggested that if she got hungry he could take her out to a special little restaurant in Havana, for obreros like himself—workers who earn their living honestly, with the sweat of their brow—María had to tell him that she couldn’t. She had just caught him staring at her in a certain way, and she didn’t want to take the chance that he might not turn out to be so saintly, even if it might hurt his feelings. Of course, he started talking about his family—his faithful wife, his eight children, his simple house in a small town way over in Cienfuegos,—and of his love of pigs even when he knew they were going to end up slaughtered—all to amuse his lovely passenger.

One thing did happen: the closer they got to Havana the more they saw roadside billboards—“Smoke Camels!” “Coca-Cola Refreshes!” “Drink Bacardi Rum!”—and alongside beautiful estates with royal-palm-lined entranceways and swimming pools were sprawling shantytowns, slums with muddy roads and naked children roaming about, and then maybe another gas station, followed by a few miles of bucolic farmland, those campesinos plowing the field with oxen, and then another wonderful estate and a roadside stand selling fresh chopped melons and fruit, followed by yet one more shantytown, each seeming more run-down and decrepit than the next. Of course the prettiest stretch snaked by the northern coastline, which absolutely enchanted María, who sighed and sighed away over the hypnotic and calming effects of the ocean—that salt and fish scent in the air, the sunlight breaking up into rippling shards on the water—everything seeming so pure and clean until they’d pass by a massive garbage dump, the hills covered with bilious clouds of acrid fumes and half crumbling sheds made of every kind of junk imaginable rising on terraces but tottering, as if on the brink of collapsing in a mud slide caused by the ash-filled rain, and, giving off the worst smell possible, a mountain of tires burning in a hellish bonfire; to think that people, los pobrecitos, lived there!

They’d come to another gas station, then a fritter place, with donkeys and horses tied up to a railing (sighing, she was already a little homesick). She saw her first fire engine that day, a crew of bomberos hosing down a smoldering shed, made of crates and thatch, near a causeway to a beach; a cement mixing truck turned over on its side in a sugarcane field, a coiling flow of concrete spewing like mierda from its bottom; then more billboards, advertising soap and toothpaste, radio shows, and, among others, a movie starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, whose faces were well known to even the guajiros of Cuba! (Another featured the enchanting visage of the buxom Mexican actress Sarita Montiel; another, the comedian Cantinflas.) Along the way, she just had to ask her new friend Sixto the ugly to stop again—a few miles or so west of Marianao, where they had come across a roadside market, just like the sort one might find in a town plaza, with stalls and long tables boasting everything from pots and pans to used clothes and shoes. Half suffocating from the swinish gases wafting into his cab, Sixto didn’t mind at all. What most caught her eye were the racks of dresses over which hung a sign.

“What’s that say, señor?” she asked, and Sixto, rubbing his eyes and pulling up on the brake, told her: “It says, rebaja”—which meant there was a sale going on. A group of women, negritas all, were perusing the racks, and so María, needing a new dress to wear in Havana, stepped from the truck and pulled her life savings, some few dollars, which she kept in a sock, out from where she had stuffed it down her dress or, to put it more precisely, from between her breasts.

Most happily and with the innocence of a farm girl, María examined the fabric and stitching of dress after dress, pleased to find that the vendors were very kind and not at all what she had expected. For a half an hour she looked around, the women working those stalls and tables complimenting her on the pristine nature of her mulatta skin, nary a pimple or blemish to mar her face (the kind of skin which had its own inner glow, like in the cosmetic ads, except she didn’t use any makeup, not back then, a glow that inspired in the male species the desire to kiss and touch her), the men giving her the up and down, the children running like scamps tugging at her skirt—

You see, my daughter; if I was incredibly good looking in my twenties, you can’t imagine what I looked like in my prime, as a girl of sixteen and seventeen—I was something out of a man’s dream, with honey skin so glowing and a face so pure and perfect that men couldn’t help wanting to possess me…. But being so young and innocent, I was hardly aware of such things, only that—well, how can I put it my love?—that I was somehow different from your typical cubanita.

That afternoon, she bought, at quite reasonable prices, certain dainty undergarments, they were so inexpensive, as well as a blouse, a pair of polka-dotted high heels, which she would have to grow accustomed to, and finally, after haggling with the vendor, she

Tennant was a woman of wealth and high social bearing who lived in a Regency mansion on Richmond Terrace, off Whitehall, in London. This rendering of her was made but a year before her marriage to Henry Morton Stanley, explorer and “Napoleon” of journalists, whose roots had been so humble that his childhood experiences and poor upbringing in Wales would have been an abstraction to her, for her own experience had never included want or deprivation. That she, the artistic and lively pearl of London society, had become involved and happily betrothed to Stanley after a well-known period of difficulties between them was one of the great mysteries of Victorian courtships.

Like just about everyone else in England, she had been caught up in the national frenzy over Africa, having followed with rapt interest the careers of Livingstone, Baker, Cameron, Speke, and Burton, among others, whose exploits were reported in all the newspapers and commemorated in books. She had been in her adolescence when the first of these explorations began, but by 1871 the greatest of all such explorers, Henry Morton Stanley, had emerged. He first became known for his search to find the Scottish missionary David Livingstone. His later activities in the region, principally in the Congo, where he had spent many years leading other expeditions, often under impossible conditions, had only increased his stature as a heroic figure in the public mind. Stanley had been so successful in opening the equatorial center of the continent that he had become one of the most famous men in England. (“Before Stanley there was no Africa,” Tennant would later write.)

Despite Stanley’s mercurial personality and the burden of his many maladies, such as chronic gastritis and numerous bouts of malaria—“the Africa in me,” he called it—their marriage had flourished, and they became one of the most famous couples in England. Tennant’s haughty circle of friends intersected with Stanley’s colleagues and acquaintances—professional relationships, for the most part. But now and then there surfaced the occasional true friendship, such as the one he had with the American writer Samuel L. Clemens, or Mark Twain, as he was most famously called.

Tennant first met Clemens at a dinner in New York City while accompanying Stanley on a lecture tour of the United States. It was an introduction that culminated, in the month of January, 1891, with an invitation to visit Clemens at his Hartford home on Farmington Avenue, where Dorothy and her mother, Gertrude, spent a most diverting few days with him and his family (at the time, Stanley was away, lecturing in Trenton and other cities in New Jersey). Thereafter, over the next decade and a half, she and Stanley saw them on various occasions, principally in London, where the Clemenses lived in the mid-1890s, then later, at the turn of the century, when they had taken up residence in England once again.

In those years, paying socials calls to the Tennant mansion on Richmond Terrace, Clemens passed many hours in their company, giving impromptu recitations for their friends at dinners, shooting billiards, and occasionally withdrawing into her studio, a canvas- and prop-cluttered room known as the birdcage, to sit as a portrait subject for Dorothy, who, in her day, was greatly admired as an artist.

It had been her wish to present a portrait of Clemens to the National Portrait Gallery, as she had done in 1893 with a commendable rendering of her explorer husband, whom she had captured in all his splendor. Dolly had made dozens of studies of Stanley during their early courtship and dozens more in the years after their marriage—each session an immersion, she felt, into the spirit of her subject, for once he had become trusting of her, fruitful conversations ensued, and his tortured soul poured naturally forth.

The same kind of exchanges took place with Clemens, from whom Dolly had learned details about his private life—his joyfulness and pride in his family; the pain of certain devastating events that made his later years difficult. She had spent perhaps twenty hours sketching him. He had been an occasionally distracted subject, fidgeting with a cigar, getting up at any moment to stretch his stiff limbs, often staring out the window to look at the Irish perennials in her garden and sometimes losing patience with the whole idea of sitting still. Yet when she got him to talking about the things that made him happy, mainly his youth in Hannibal—the perpetually springlike wonderland from which his most memorable characters flowed—time stopped, his discomforts left him, and a serenity came over his famously leonine countenance.

* * *

• “As you surely know, Dolly, I have always been fond of Stanley. Not that he’s the easiest person to understand, but he kind of grows on a body. His convictions, his work ethic, his knowledge of many things—these qualities appeal to me, even if I do not always agree with him. He’s not the easiest person to get along with, by any stretch, which, by the way, I do not mind. And he is one of the moodiest people I have ever known, besides myself, and has been so ever since I first knew him. Our saving grace is that we have similar temperaments and can disagree or feel gloomy or cantankerous around each other without standing on ceremony; we are just that way.”

He had paused then to relight a cigar, drawing from his vest pocket a match, which he struck against the heel of his shoe.

“Somehow, ours has been a friendship that’s lasted. I cannot say that he is as close to me as my best friends in the States, but I hold him in considerable esteem just the same. The fact is we go back together to simpler times, an enviable thing. As much as he has changed over the years, he is not so different from the young man I met years ago, on a riverboat—you know of this, do you not?”

“He told me once that you met long ago.”

“Indeed we did. It was a friendship that commenced by chance—on the boiler deck of a steamboat heading upriver, between New Orleans and St. Louis…in the autumn of 1860, just before the Civil War, during my days as a Mississippi River pilot.”

A plume of bluish smoke.

“Stanley was traveling in the company of his adoptive American father, a merchant trader who plied the Mississippi port towns. He was Stanley’s mentor in New Orleans and a great influence on his manner of dress and grooming, and he did much, as I remember, to advance his son’s education, which by my lights was already considerable. Stanley was one of the better-read young men on that river. Of course I already knew some bookish types; Horace Bixby, a fellow pilot, got me to reading William Shakespeare, and occasionally I’d meet some traveling professor or any number of journalists with whom I could sometimes talk about literature. But Stanley, in those days, with his good common-school English education—one that he was modest about—was quite a cut above the average Mississippi traveler. And he seemed the most guileless and unassuming fellow one could ever encounter, to boot.”

He puffed on his cigar again, and even as he was speaking, conjured, in his mind, the sight of drowsy still waters at dusk, campfires along the Mississippi River dotting the shore with light, the stars beginning to rise.

“He always had a book in hand and seemed anxious to learn about the world: I found myself beguiled by him, and I was touched that he seemed to be in need of a friend. We were both young men—I was twenty-five or so, and I believe Stanley was then about nineteen, the same age as my dear recently deceased younger brother, also named Henry. I suppose I was ready and willing to befriend Stanley for that reason alone, though who knows how or why chance happens to place a person in one’s path. Whatever the mysterious cause, our friendship blossomed and eventually led to a quite interesting run of years. I am surprised that he has not told you more about our beginnings.”

* * *

• She sits down to write a letter in the parlor of her mansion, the interior unchanged from the day Stanley had died, three years before, at six in the morning, just as Big Ben was ringing in that hour from a distance. In its rooms many of Stanley’s possessions and keepsakes remain where she had put them; in the hallways, framed photographs of Stanley on safari, Stanley in Zanzibar with his native porters, Stanley poised on a cliff in the rainbow mists of Victoria Falls. A bookcase bears a multitude of first editions and translations of his African memoirs. Atop the numerous tables and travertine pedestals are a variety of ornate freedom caskets from cities like Dundee, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Swansea, and Manchester, each honoring Stanley for one or the other of his African exploits. Here and there, hanging on a wall, are plaques that Stanley had particularly liked. One of them, harking back to 1872, when he had become famous for finding Livingstone in the wilds of Africa, reads:

A COMMON COUNCIL

HOLDEN IN THE CHAMBER OF GUILDHALL, OF THE CITY OF LONDON

ON THURSDAY, THE 21ST DAY OF NOVEMBER, 1872,

RESOLVED UNANIMOUSLY

THAT THIS COURT DESIRES TO EXPRESS ITS GREAT APPRECIATION OF THE EMINENT SERVICES RENDERED BY

MR. HENRY MORTON STANLEY

TO THE CAUSE OF SCIENCE AND HUMANITY BY HIS PERSISTENT AND SUCCESSFUL ENDEAVORS TO DISCOVER AND RELIEVE THAT ZEALOUS AND PERSEVERING

MISSIONARY AND AFRICAN TRAVELLER,

DR. DAVID LIVINGSTONE,

THE UNCERTAINTY OF WHOSE FATE HAD CAUSED SUCH DEEP ANXIETY, NOT ONLY TO HER MAJESTY’S SUBJECTS, BUT TO THE WHOLE CIVILISED WORLD.

There are framed maps of Africa and bronze busts of Stanley lining the hallways and several Minton biscuit figurines of Stanley—the kind that were sold for years in the tourist shops of Piccadilly—set out on a parlor table. On a desk in Lady Stanley’s own study, just down the hall from her painting studio, sit her commonplace books and a manuscript of her own writings—the fragments of a memoir (never to be completed) called My Life with Henry Morton Stanley—alongside a plaster cast of Stanley’s left hand, which she keeps for good luck. But there is also much more about Stanley—diplomas, royal decrees, gold medals (the Order of Leopold and the Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath from the late queen; the Grand Cordon of the Imperial Order of Medijdieh from the khedive of Egypt)—to come upon in that house. There are also many other keepsakes—old compasses, sextants, and other instruments as well as various native African artifacts, such as Zulu fly whisks, spearheads, and phallic oddities brought back by Stanley after his journeys—on display in a curio cabinet.

As she writes, his presence is inescapable. Even as she is about to remarry, in a few weeks, Lady Stanley has never gotten around to removing a thing from Stanley’s private bedroom—they had sometimes slept apart. His wardrobe closet still contains the Savile Row suits he favored, along with his shirts, his lace bow ties, his vests, suspenders, stockings, his walking sticks, and many pairs of his distinctively smallish-size shoes. Even his bedside table has remained as it was the morning he left her—a pair of wire-rimmed spectacles sitting atop the pages of a Bible, opened to the chapters of Genesis. Nor has she touched the mantel clock with Ottoman numerals, except to rewind it nightly; nor has she removed from that chamber the other books he had taken much comfort in: Gladstone’s Gleanings of Past Years, a volume of autobiographical essays that Stanley admired despite his personal dislike of the man (“I detect the churchgoing, God-fearing, conscientious Christian in almost every paragraph,” he had written); the histories of Thucydides; and two novels, David Copperfield by Charles Dickens (“That boy was me, in my youth” he once said) and another by his old friend Mark Twain, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn—the very copy Stanley had carried with him on his final expedition to Africa.

And along with the framed photographs he had asked to be placed near him as he had lain in his bed, beside those of Denzil, Queen Victoria, and Livingstone, there are several oil studies made by Lady Stanley in earlier days: Stanley sitting on the lawn of their country estate in Surrey; a portrait of Samuel Clemens that Dolly had commenced some years before in her studio.

May 11, 1907

2 Richmond Terrace, Whitehall, London

Dearest Sam,

I have been going through Henry’s many papers and notebooks in my attempt to fill out his history. In his study, he kept several large cabinets of facsimiles of letters, old manuscripts, and notebooks. He was a hoarder of all things pertaining to himself, perhaps for the sake of the historical record, and so, as you may well imagine, there has been quite a bit to consider. Lately, I have made it my habit to spend a part of my days searching for materials pertinent to the story of his life—no easy task, given their volume. It is a labor I have conducted in slow but steady measures.

In any event, I have come across a manuscript that I had never seen before. It is a manuscript I believe Henry had commenced shortly after we had visited New Orleans in the autumn of 1890, while on tour for dear Major Pond, when Henry’s memories of his life there, after an absence of thirty years, had been freshly reawakened. Since much of it was written out on stationery from hotel and steamship lines, with which I am familiar, having accompanied Stanley on his tours of the States and Australia in 1891 and 1892, I date its composition to that time. At first, I had thought the manuscript a preliminary version of the chapters regarding his first years in his adopted country, which Henry would later refine. But as I read on I was surprised to see how much it diverged from what he later left as the “official” version, for these pages contain an untold story. And that story has presented me, as the amateur compiler of his life, with a very great dilemma.

And here it is: In the completed sections of the autobiography, which he approved for publication, he plainly states that Henry Hope Stanley, the merchant trader from New Orleans whom he considered his second father, had vanished during a journey to Cuba, where he had a business: “He died in 1861. I did not learn this until long afterward,” is how he summarized it. Yet the “cabinet” manuscript, if I may call it so, seems to be an elaborate explanation of Henry’s search for his father in Cuba, a journey he claims, in these pages, to have made in the days of late March and early April of 1861, with you.

Samuel, as delighted as I had been over this unexpected revelation, you must imagine the state of perplexity it put me in. For in this manuscript contradicts what Henry once told me about his experiences in Cuba, which he claimed to have visited only once, in 1865; he said that he made that journey to see his adoptive father’s grave for himself, the elder Mr. Stanley having been buried “in some churchyard near Havana.” And the only time he had mentioned you in relation to his early days in America—in fact, while we were strolling down the Vieux Carré of New Orleans during our 1891 journey there—he referred to your chance meeting “along some stretch of the Mississippi,” aboard a riverboat, years ago. But he never elaborated about your early friendship, nor did he begin to hint at the extent to which he had, in fact, privately written about you. Since it was obviously Henry’s wish to exclude this narrative from his official story, I am assuming that he had his reasons, upon which I hope you will shed some light. I have taken the liberty of sending you a typescript version (Henry’s original, often written in a post-malarial state, suffers from stains and an addled penmanship). Once you have read it, I hope you can answer this question: Was it so, Samuel?

Copyright © 2015 by the Estate of Oscar Hijuelos

Over forty years before, when Nestor Castillo’s future love, one María García y Cifuentes, left her beloved valle in the far west of Cuba, she could have gone to the provincial capital of Pinar del Río, where her prospects for finding work might be as good—or bad—as in any place; but because the truck driver who’d picked her up one late morning, his gargoyle face hidden under the lowered brim of a lacquered cane hat, wasn’t going that way and because she’d heard so many things—both wonderful and sad—about Havana, María decided to accompany him, that cab stinking to high heaven from the animals in the back and from the thousands of hours he must have driven that truck with its loud diesel engine and manure-stained floor without a proper cleaning. He couldn’t have been more simpático, and at first he seemed to take pains not to stare at her glorious figure, though he couldn’t help but smile at the way her youthful beauty certainly cheered things up. Okay, he was missing half his teeth, looked like he swallowed shadows when he opened his mouth, and had a bulbous, knobbed face, the sort of ugly man, somewhere in his forties or fifties—she couldn’t tell—who could never have been good looking, even as a boy. Once he got around to tipping up his brim, however, she could see that his eyes were spilling over with kindness, and despite his filthy fingernails she liked him for the thin crucifix he wore around his neck—a sure sign, in her opinion, that he had to be a good fellow—un hombre decente.

Heading northeast along dirt roads, the Cuban countryside with its stretches of farms and pastures, dense forests and flatlands gradually rising, they brought up clouds of red dust: along some tracks it was so hard to breathe that María had to cover her face with a kerchief. Still, to be racing along at such bewildering speeds, of some twenty or thirty miles an hour, overwhelmed her. She’d never even ridden in a truck before, let alone anything faster than a horse and carriage, and the thrill of traveling so quickly for the first time in her life seemed worth the queasiness in her stomach, it was so exciting and frightening at the same time. Naturally, they got to talking.

“So, why you wanna go to Havana?” the fellow—his name was Sixto—asked her. “You got some problems at home?”

“No.” She shook her head.

“What are you gonna do there, anyway? You know anyone?”

“I might have some cousins there, from my mamá’s side of the family”—she made a sign of the cross in her late mother’s memory. “But I don’t know. I think they live in a place called Los Humos. Have you heard of it?”

“Los Humos?” He considered the matter. “Nope, but then there are so many hole-in-the-wall neighborhoods in that city. I’m sure there’ll be somebody to show you how to find it.” Then, picking at a tooth with his pinkie: “You have any work? A job?”

“No, señor—not yet.”

“What are you going to do, then?”

She shrugged.

“I know how to sew,” she told him. “And how to roll tobacco—my papito taught me.”

He nodded, scratched his chin. She was looking at herself in the rearview mirror, off which dangled a rosary. As she did, he couldn’t resist asking her, “Well, how old are you anyway, mi vida?”

“Seventeen.”

“Seventeen! And you have nobody there?” He shook his head. “You better be careful. That’s a rough place, if you don’t know anyone.”

That worried her; travelers coming through her valle sometimes called it a city of liars and criminals, of people who take advantage. Still, she preferred to think of what her papito once told her about Havana, where he’d lived for a time back in the 1920s when he was a traveling musician. Claimed it was as beautiful as any town he’d ever seen, with lovely parks and ornate stone buildings that would make her eyes pop out of her head. He would have stayed there if anybody had cared about the kind of country music his trio played—performing in those sidewalk cafés and for the tourists in the hotels was hard enough, but once that terrible thing happened—not just when sugar prices collapsed, but when the depression came along and not even the American tourists showed up as much as they used to—there had been no point to his staying there. And so it was back to the guajiro’s life for him.

That epoch of unfulfilled ambitions had made her papito sad and sometimes a little careless in his treatment of his family, even his lovely daughter, María, on whom, as the years had passed, he sometimes took out the shortcomings of his youth. That’s why, whenever that driver Sixto abruptly reached over to crank the hand clutch forward, or swatted at a pesty fly buzzing the air, she’d flinch, as if she half expected him to slap her for no reason. He hardly noticed, however, no more than her papito did in the days of her own melancholy.

“But I heard it’s a nice city,” she told Sixto.

“Coño, sí, if you have a good place to live and a good job, but—” And he waved the thought off. “Ah, I’m sure you’ll be all right. In fact,” he went on, smiling, “I can help you maybe, huh?”

He scratched his chin, smiled again.

“How so?”

“I’m taking these pigs over to this slaughterhouse, it’s run by a family called the Gallegos, and I’m friendly enough with the son that he might agree to meet you…”

And so it went: once Sixto had dropped off the pigs, he could bring her into their office and then who knew what might happen. She had told him, after all, that she’d grown up in the countryside, and what girl from the countryside didn’t know about skinning animals, and all the rest? But when María made a face, not managing as much as a smile the way she had over just about everything else he said, he suggested that maybe she’d find a job in the front office doing whatever people in those offices do.

“Do you know how to read and write?”

The question embarrassed her.

“Only a few words,” she finally told him. “I can write my name, though.”

Seeing that he had made her uncomfortable, he rapped her on the knee and said, “Well, don’t feel bad, I can barely read and write myself. But whatever you do, don’t worry—your new friend Sixto will help you out, I promise you that!”

She never became nervous riding with him, even when they had passed those stretches of the road where the workers stopped their labors in the fields to wave their hats at them, after which they didn’t see a soul for miles, just acres of tobacco or sugarcane going on forever into the distance. It would have been so easy for him to pull over and take advantage of her; fortunately this Sixto wasn’t that sort, even if María had spotted him glancing at her figure when he thought she wasn’t looking. Bueno, what was she to do if even the plainest and most tattered of dresses still showed her off?

Thank goodness that Sixto remained a considerate fellow. A few times he pulled over to a roadside stand so that she could have a tacita of coffee and a sweet honey-drenched bun, which he paid for, and when she used the outhouse, he made a point of getting lost. Once when they were finally on the Central Highway, which stretched from one end of the island to the other, he just had to stop at one of the Standard Oil gas stations along the way, to buy some cigarettes for himself and to let that lovely guajira see one of their sparkling clean modern toilets. He even put a nickel into a vending machine to buy her a bottle of Canada Dry ginger ale, and when she belched delicately from all the burbujas—the bubbles—Sixto couldn’t help but slap his legs as if it was the funniest thing he had ever seen.

He was so nice that she almost became fond of him despite his ugliness, fond of him in the way beautiful women, even at so young an age, do of plain and unattractive—hideous—men, as if taking pity on an injured dog. As they started their approach towards one of the coastal roads—that air so wonderful with the scent of the gulf sea—and he suggested that if she got hungry he could take her out to a special little restaurant in Havana, for obreros like himself—workers who earn their living honestly, with the sweat of their brow—María had to tell him that she couldn’t. She had just caught him staring at her in a certain way, and she didn’t want to take the chance that he might not turn out to be so saintly, even if it might hurt his feelings. Of course, he started talking about his family—his faithful wife, his eight children, his simple house in a small town way over in Cienfuegos,—and of his love of pigs even when he knew they were going to end up slaughtered—all to amuse his lovely passenger.

One thing did happen: the closer they got to Havana the more they saw roadside billboards—“Smoke Camels!” “Coca-Cola Refreshes!” “Drink Bacardi Rum!”—and alongside beautiful estates with royal-palm-lined entranceways and swimming pools were sprawling shantytowns, slums with muddy roads and naked children roaming about, and then maybe another gas station, followed by a few miles of bucolic farmland, those campesinos plowing the field with oxen, and then another wonderful estate and a roadside stand selling fresh chopped melons and fruit, followed by yet one more shantytown, each seeming more run-down and decrepit than the next. Of course the prettiest stretch snaked by the northern coastline, which absolutely enchanted María, who sighed and sighed away over the hypnotic and calming effects of the ocean—that salt and fish scent in the air, the sunlight breaking up into rippling shards on the water—everything seeming so pure and clean until they’d pass by a massive garbage dump, the hills covered with bilious clouds of acrid fumes and half crumbling sheds made of every kind of junk imaginable rising on terraces but tottering, as if on the brink of collapsing in a mud slide caused by the ash-filled rain, and, giving off the worst smell possible, a mountain of tires burning in a hellish bonfire; to think that people, los pobrecitos, lived there!

They’d come to another gas station, then a fritter place, with donkeys and horses tied up to a railing (sighing, she was already a little homesick). She saw her first fire engine that day, a crew of bomberos hosing down a smoldering shed, made of crates and thatch, near a causeway to a beach; a cement mixing truck turned over on its side in a sugarcane field, a coiling flow of concrete spewing like mierda from its bottom; then more billboards, advertising soap and toothpaste, radio shows, and, among others, a movie starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, whose faces were well known to even the guajiros of Cuba! (Another featured the enchanting visage of the buxom Mexican actress Sarita Montiel; another, the comedian Cantinflas.) Along the way, she just had to ask her new friend Sixto the ugly to stop again—a few miles or so west of Marianao, where they had come across a roadside market, just like the sort one might find in a town plaza, with stalls and long tables boasting everything from pots and pans to used clothes and shoes. Half suffocating from the swinish gases wafting into his cab, Sixto didn’t mind at all. What most caught her eye were the racks of dresses over which hung a sign.

“What’s that say, señor?” she asked, and Sixto, rubbing his eyes and pulling up on the brake, told her: “It says, rebaja”—which meant there was a sale going on. A group of women, negritas all, were perusing the racks, and so María, needing a new dress to wear in Havana, stepped from the truck and pulled her life savings, some few dollars, which she kept in a sock, out from where she had stuffed it down her dress or, to put it more precisely, from between her breasts.

Most happily and with the innocence of a farm girl, María examined the fabric and stitching of dress after dress, pleased to find that the vendors were very kind and not at all what she had expected. For a half an hour she looked around, the women working those stalls and tables complimenting her on the pristine nature of her mulatta skin, nary a pimple or blemish to mar her face (the kind of skin which had its own inner glow, like in the cosmetic ads, except she didn’t use any makeup, not back then, a glow that inspired in the male species the desire to kiss and touch her), the men giving her the up and down, the children running like scamps tugging at her skirt—

You see, my daughter; if I was incredibly good looking in my twenties, you can’t imagine what I looked like in my prime, as a girl of sixteen and seventeen—I was something out of a man’s dream, with honey skin so glowing and a face so pure and perfect that men couldn’t help wanting to possess me…. But being so young and innocent, I was hardly aware of such things, only that—well, how can I put it my love?—that I was somehow different from your typical cubanita.

That afternoon, she bought, at quite reasonable prices, certain dainty undergarments, they were so inexpensive, as well as a blouse, a pair of polka-dotted high heels, which she would have to grow accustomed to, and finally, after haggling with the vendor, she

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Beautiful María of My Soul

Oscar Hijuelos

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved