- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

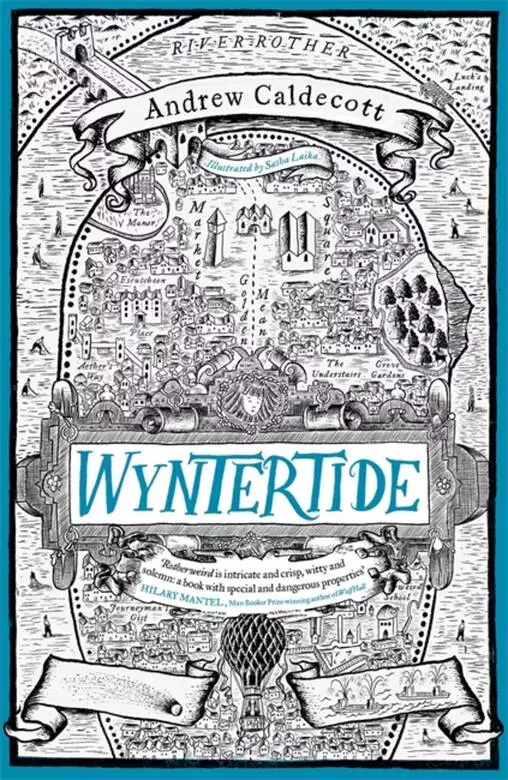

'Intricate and crisp, witty and solemn: a book with special and dangerous properties' Hilary Mantel on Rotherweird 'Baroque, Byzantine and beautiful - not to mention bold' - M.R. Carey on Rotherweird WELCOME BACK TO ROTHERWEIRD For four hundred years, the town of Rotherweird has stood alone, made independent from the rest of England to protect a deadly secret. But someone is playing a very long game. An intricate plot, centuries in the making, is on the move. Everything points to one objective - the resurrection of Rotherweird's dark Elizabethan past - and to one date: the Winter Equinox. Wynter is coming . . .

Release date: May 31, 2018

Publisher: Jo Fletcher Books

Print pages: 496

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Wyntertide

Andrew Caldecott

63 Anno Domini. Britannia.

Caligatae is the name they have coined for themselves – ‘footsloggers’, men who march the known world, anywhere that’s worthwhile.

He eyes his caligae. More than a Roman soldier’s sandals, caligae are an emblem of Empire, their hobnailed soles stamping the alien earth. Yet practicalities matter too: they serve well in his homeland, and in Africa, where the sand flows through, and on any road anywhere – but in this pathless backwater of Britannia, with its midges, ticks and leeches, caligae let in the natural enemies. The woollen foot-sleeves help, but biting insects still climb the fibres to softer flesh. Here there are always quid pro quos.

His name, once Gregorius, is now Gorius: the army needs short names, shoutable.

He is the legion’s speculator, the lead scout. He likes the word for sounding like the role it describes: a mix of looking, hope, guesswork and working alone.

Ferns tickle his ears; the helmet is off, lest it catch the light. He reads the land as those below will read it: the folds, the shifting skyline, the cross-hatching of bracken and earth. With his tanned skin, he blends in.

He has been here an hour. Time drags when a scene is familiar – the standing stones, the doomed men in white robes, the primitive huts fashioned with clay, animal dung and straw. Yet the idiocy of these particular barbari defies precedent, for they abandon the island, their one defensible position – some by coracle, others filing in full view through open meadowland – to converge on a wood which rises steeply to the valley rim: a trap of their own making.

Cavalry canter along the river, spearing the beached coracles to cut off escape by water. The infantry, dividing into three equal sections, descends from the north. The orders are short, the reaction instant.

Gorius admires the strategy, honed by months of similar operations and the perfection of Roman manoeuvre. About the slaughter of the innocent, he is more squeamish; he looks away. To the south beyond the river, an earthy prominence dominates the flat marshland. He thinks of a burial mound, although there is no path in.

He resumes his watch on the approaching battle. The barbari have retreated into the trees. This is child’s play: skirmishers go in first, fanning out to seal the sides. Cavalry comb the grassland for covered pits, stabbing at the ground and finding none. The legionaries leave their shields and javelins beside the wood; in the congested trees, a short sword is quicker.

The nape of his neck tingles. Where are the cries of the women and children? He recalls the mix of unease and reverence this settlement generates in neighbouring communities. He hears only slashed undergrowth and soldiers’ oaths; orders lose certainty. The legionaries drift out, as hounds might after losing a scent.

This is his task, Gorius with his hunter’s eyes: finding the hidden ways, forestalling ambush. He marks their vanishing point, dashes to his tethered horse and gallops down.

‘Now you can earn your bloody keep,’ growls his tribune, Ferox by nickname and ferox by nature.

Gorius does not want the ground more trampled than it is. ‘Call them all out, sir – leave this to me.’

‘And when you find them, what then?’ Ferox follows his speculator in, sword drawn.

Gorius pauses, points and moves on, like the dappled hunting dogs in Gaul. It is difficult translating unfamiliar ground seen from above to the place itself, but he narrows his search to a deep hollow whose upward slope is too severe to climb quickly; nobody has tried. Hobnailed caligae leave spoor, but smoother prints dominate here, bare feet. He crawls on all fours as Ferox mocks, and then he finds it: a lattice of twig and fern fronds, near invisible, held to the ground with pegs. He lifts them to reveal a white tablet, fine as any Roman marble, and incised with a flower. The workmanship is exquisite, surely beyond these savages. Ferox runs his sword across it, leaving not a scratch.

‘A gate,’ suggests Gorius. ‘Has to be.’

The lines on Ferox’s face map a man with little laughter, but now his eyes sparkle as he slaps his thighs, causing the leather thongs of his uniform to swing back and forth between his legs. He bellows like a bull: a gate for grown men, one metre square?

Gorius rests the palm of his hand on the tile. The dark hairs on his wrist stand proud, prickling with energy. Tentative now, he steps forward – and disappears.

Laughter strangling to a snarl, Ferox follows.

977 Anno Domini. A remote monastery.

By dint of one monk’s remarkable chronicle of events, as impartial in its treatment of saints as of pagan kings, Jarrow is still reputed to be, two centuries on, the greatest centre of learning north of Rome.

Brother Hilarion in his humbler monastery nurses a like ambition, which brings him to his abbot’s office.

‘I understand you have an urge to set down like Brother Bede.’

‘Yes – but not the history of men.’

‘And what is wrong with men?’

Brother Hilarion does not say what he thinks. If Man is made in God’s image, God must be terrible indeed.

‘I prefer the gentler days of Creation – flora, fauna and celestial happenings.’

The abbot nods. ‘They say you have a gift for description, and a special eye.’

This is true. No leaf or feather or star is quite like another to Hilarion. ‘But I fear I seek my own renown – that I have fallen prey to pride.’

‘Everyone talks of Jarrow, nobody of us – and who accuses Brother Bede of vanity?’ The abbot crosses himself as a sign of respect. ‘How far would you travel?’

Brother Hilarion feels his world turn from a cell three steps square to miles and miles of forest, marsh and pasture. An epic answer comes without thinking. ‘I would journey from the southern sea to the northern wall.’

‘All of Britannia that is! Take two horses, supplies, whatever you need by way of paper, quills and ink. A lay assistant will join you. Young Harfoot is strong. He can bear arms – and he has worked in the scriptorium.’

Brother Hilarion hangs his head as the abbot blesses him – a rarity reserved for the most demanding tasks. The abbot sees Hilarion to the door. ‘When you return, you will dedicate this work—’

‘To the monastery.’

‘By name only?’

‘I will include my humble and distinguished abbot.’

A wave and a rare smile. He has found the right response.

Within an hour of leaving they encounter a new butterfly: papilio.

‘Pliny the Elder recorded them so why shouldn’t we?’ declares the monk.

Harfoot unpacks the instruments of record with a tidy eye. This is to be the first entry on the first page. He records the day, the month, the orange tips to the white wings and the insect’s size by a wooden rule he has developed for the purpose. An hour passes before they move on.

They have an instant affinity. Harfoot’s sunny disposition lightens the intensity of his master’s vision. Their journey will end forty years later with a phenomenon that will make the sweeping events in Brother Bede’s great chronicle look ordinary.

December 1017. The Rotherweird Valley.

Forty years on, and the mission has changed. Their early books filled too quickly with much that was commonplace and they bequeathed them to monasteries along the way. For the last decade, there has been but one book, home only to the local and the rare.

Word of mouth brings them to this escarpment rim.

The valley below keeps its own weather, a different degree of winter. A frozen river encircles an island, in appearance a bone necklace.

‘What were those local mutterings?’ asks Brother Hilarion. He is forgetful now, his voice feeble, speech an effort.

‘A flying serpent.’

The monk needs only a cue. ‘Ah yes: rare rocks and butterflies with blue-white wings, if we had time to wait a season.’

‘And a plant that never flowers,’ adds Harfoot.

The furrows in Brother Hilarion’s face shape to a smile. ‘Enough to hazard the journey then,’ he says, ‘even on the shortest day of the year.’

Their two ponies, refractory and apprehensive, pick their way. A huge rock stabs the sky from the island’s summit like an accusing finger. A circular hole near the apex catches the light, suggestive of an eye. In the marshland to the southeast is a turfed prominence, apparently manmade, terra firma in the bog. Brother Hilarion feels beset by pagan images.

He notes the grey threads in his younger companion’s hair, and the bald crown, which now matches his: Nature’s tonsure is testimony to so many cliff paths, moors and mountains traversed together, as are their feet protruding through their sandals like tuberous roots. Age has deepened the bond between them, as it has altered the dependencies. Harfoot’s tasks are multiplying. He describes for Brother Hilarion the finer details of the view, the stealthier sounds, and his vocabulary burgeons in consequence.

On reaching the valley floor, they look skywards and Harfoot points. ‘You see the darkness in the blue, Brother.’ Their magnum opus has a page devoted to Nature’s more peculiar clouds.

‘How are they shaped?’

‘Like anvils in a forge, one south, one north.’

‘Quill, good Harfoot,’ calls the monk, although the familiar cry is unnecessary for Harfoot has already unwrapped quill, ink and parchment. ‘We’ve never seen two at the same time.’

‘These are different,’ he suggests, ‘portentous even.’

So they are: blacker, their edges sharp as quillwork, sitting like rival armies forming for battle.

Harfoot does the writing now the monk’s crabbed fingers have grown rigid. Hilarion is ailing, his legs stiffening too, and his breathing is stertorous, like pebbles in a sieve – but as the body diminishes, so the spirit burns brighter. So much to do, so little time . . .

‘We’ll use your name for these: incus maior,’ declares Hilarion; always eager to give his companion credit.

Lightning leaps from one cloud to the other: a strike from Vulcan’s hammer. Harfoot would like to bottle these clouds. Nobody will believe them otherwise. However . . .

‘Shelter?’ he advises, in the respectful guise of a question.

‘Ah, we have time,’ the brother murmurs, staring upwards.

There are huts sprawling across the lower levels of the main island, but they see no one, despite the livestock tethered near the single bridge that runs to the flatter, less obvious island – until a man clothed in a muddle of pelt and hide bounds from the woods. He stops beside them – or rather, he continues to run, although stationary, muscles coiling in his arms and legs, ready to take off again at any moment. The skin is burnished, but it is the face which arrests. The eyes are welcoming, the mouth generous and the radiating lines humorous, but for Brother Hilarion, this pleasing mask holds suffering beneath.

‘Harfoot would like to bottle these clouds. Nobody will believe them otherwise.’

His diagnosis is familiar. ‘Are you baptised, my son?’

‘Sum Gorius.’

Latin in this backwater? The mystery deepens.

‘They talk of a rare plant,’ interjects Harfoot.

The knees continue to rise and fall as he points to the flatter meadow. ‘A plant so rare it fruits but once in a thousand years,’ replies the man – Gorius – before slipping back into Latin. ‘Sequi me.’ Follow me. He gives the command a near-religious emphasis.

He leads them at marching pace to the meadow, where, beneath a stand of scraggy oaks, spreads the evergreen, procumbent colony. In this blessed month of the Nativity, on the shortest day of the year, the flowers are gone, but the fruit, a rich blue-purple, still hangs at joint of stalk and axil. Beneath each round berry lurks a tiny red thorn.

‘Pick but one,’ advises Gorius. ‘She is most jealous of her fruit.’

How quaint these country folk are, thinks Harfoot, but Brother Hilarion, still the better naturalist, is less dismissive. He has seen nothing resembling this plant anywhere from the southern sea to the northern wall.

The scratch of the quill sounds loud in the stillness, but not for long. The ponies feel it first, heads up, wide-eyed as they flick the frost from their muzzles. A knifing wind rises; the two inci close and ignite, flashing silver, and thunder booms as Harfoot, hands quivering in the cold, hurriedly wraps the book in layers of leather and sheepskin.

‘Go back,’ cries Gorius, pointing the way they have come. ‘There is a holy house beyond the rim.’

Then he runs, and the hail erupts, swirling, the size of small pebbles, sharp enough to mark the skin. The ponies are too unruly to ride so Harfoot holds them fast as, step by step, heads bowed to the waist, they edge towards the upwards path. Thunder, hail and wind with their distinctive voices, the roar, swish and howl, batter the ears – but they are mere whispers set against the new noise: a grinding from the earth itself, Sisyphus pushing his rock. The ground beneath them, now white, shivers and slides—

—and abruptly, everything stops, leaving utter stillness in its wake. The hail softens to snow. Harfoot is holding the ponies with one hand and anxiously supporting Brother Hilarion with the other. The old monk’s face is grey as stone.

At the rim of the valley they stop and turn to look back at the island – and now they understand. The henge with the eye atop the hill has vanished into thin air.

This is God’s way of telling them this is journey’s end.

Miraculum.

Brother Hilarion rests a hand on his companion’s shoulder.

‘You must build a church there – on the brow of the island. Upon this rock . . .’

*

Brother Hilarion dies peacefully on the eve of the Nativity.

Harfoot buries him in a field beside the monastery above the valley rim.

The following Mayday he takes his vows and, as soon as the abbot will allow, retraces his steps to the valley.

So long a pagan outpost, the community embraces the new, softer theology: love thy neighbour, a final judgement that favours the just and the poor, a bloodless sacrifice in a sliver of unleavened bread. Harfoot preaches on the island’s prominence, the hill of the vanishing henge. It is, he says, a sign. Here, in Rotherweird, at this very spot, they must build a house for the true God.

He will call it the Church of the Traveller’s Rest.

1035. Rotherweird Island.

The sky is clear and frost this sharp is colder than snow and more beautiful. The four circular holes in the ornate stone cross atop the church tower are chalked in, filled with white.

Brother Harfoot has found fulfilment. He inhabits a modest cell behind the church, a nighttime fire of applewood his single luxury; he inhales the scent like balm. In tribute to his friend, he finishes the book with a narrative of their last travelling day: the two battling inci, the running man, the vanishing henge and the flower that fruits once in a thousand years.

The new church has drawn men who turn wood, carve stone and colour walls, and Harfoot allows their energies to flourish as they labour for their afterlife. The fantastical scenes on the walls of the tower are uncomfortably real, but he does not ask their origins.

He knows the person interrupting his evening prayer as a local man of means, the weaver of stories who hired the men and directed the frescoes – which image on which wall; the mixing of colours; who will work on what. He holds a perfect sphere of rock, which neatly fills the palm of his hand, a swirl of colours like the painted wooden balls in a rich boy’s toy chest.

Harfoot, the mighty traveller, has never seen its like before. ‘Where’s it from?’

‘A peat-cutter found it nearby. He thought it should stay here.’

Harfoot weighs the stone in the palm of his hand. ‘There was a henge where the church is now. It had a circular hole.’

‘Locals called it the eye of the winking man.’

‘What colour was it?’ asks Harfoot.

‘Veined rock, as I remember, and not unlike this.’

‘And size?’

‘There or thereabouts.’

‘If it’s the eyeball of the winking man, it should be kept in God’s house,’ he says as he accepts the gift.

*

In the marches of the night, a disturbing thought occurs. Did the sphere cause the vanishing? If so, to where? In the frescoes, the henge is there on one wall, on the next the church in its place – and then the henge again somewhere unrecognisable.

A puzzle best left, he decides.

1

A Problem

How to thank Ferensen for that remarkable summertime feast?

Bill Ferdy, landlord of The Journeyman’s Gist, under whose observant stewardship grudges were settled, prospective couples were introduced, gloom dispelled and problems solved or softened, listened more than he spoke, treated all comers equally, respected confidences, never served a drunk – and brewed that remarkable beer, Old Ferdy’s Feisty Peculiar. His approach in all matters flowed from attention to detail and a desire to please, which was why this small but tricky question troubled him considerably.

Ferdy knew what an effort the old man must have made, with his Elizabethan theme, the restoration of his woodland maze and clearing his tower of its miscellany of books and outlandish objects to accommodate them. Ferdy pondered how exhausting near-immortality must be. Ferensen, as Hieronymus Seer, had witnessed the murder of Sir Henry, their childhood benefactor, only to suffer with his sister under Geryon Wynter’s rule, culminating in his immersion in the mixing-point with consequences they could only guess at. He likened him to the blasted oak at the border of his farm: still in leaf, supporting nature in many forms, but wearing the scars of his long existence.

Ferensen had declined all help, insisting that the feast would be more than a thanksgiving. The company must still solve the mystery at the heart of events: who was Robert Flask, the vanished School Historian? Ferensen introduced the task as an after-dinner game. The clues – a notebook, an address, a crossword anagram, the skull of Ferox the weaselman, the tapestries – all combined to reveal that Flask must be Calx Bole, Wynter’s servant – and thanks to Wynter’s abuse of the mixing-point in Lost Acre, a shapeshifter, and, like Ferensen, centuries old.

In the days after the dinner, as summer waned, Ferensen had changed. He turned monosyllabic, spending days on end immured in his tower. That, however, did not make him immune to the restorative effect of gratitude. So, how to thank Ferensen?

*

Knock-knock. Ring. Knock-knock-knock.

Cursing, Hayman Salt, Head Municipal Gardener and much else besides, tramped to the front door, where he was relieved to find one of the few men he considered worthy company.

‘Bill!’

‘Hayman Salt.’

One callused hand firmly shook the other.

‘Come through.’ Salt escorted Ferdy to his conservatory, where his dead Lost Acre cultivars had been swept into a corner to compost, innocuous as a spill of tobacco. More conventional blooms had replaced them on the wooden racks.

‘I’m done with Lost Acre and adventure,’ said Salt.

‘You mean the Green Man changed you?’

Salt’s brief merger with the Midsummer flower had deepened his affinity with trees and shrubs. Now he sensed their hidden illnesses, what boughs to lose, when to irrigate, drain or enrich. ‘I’m a better gardener, that’s for sure, and better morally, too.’ Salt paused. ‘But that’s enough of me. To what do I owe this pleasure?’

‘It’s about . . .’ Ferdy stopped, then mouthed the name ‘Ferensen’, whose existence and identity they had all sworn to keep secret.

‘Ah.’ Salt ushered Ferdy into his sitting room, and as his guest examined the botanical prints covering the walls, he produced a bottle of Feisty Peculiar. ‘They tell me it’s rather good,’ said Salt with a wink.

Ferdy held his own brew to the light before passing it under his nose. ‘Last year’s – thinner than the best, maybe, but not bad.’

‘So: what about Ferensen?’ asked Salt.

‘He’s in a poor way.’

‘He shouldn’t be – he masterminded everything.’

‘We’re not sure about that, remember?’

Salt did remember the unsettling thought that they’d all been manoeuvred into saving Lost Acre to further some hidden design of Calx Bole alias Flask alias Ferox alias who-else-besides?

Ferdy put his proposal. ‘We haven’t thanked him for that splendid dinner. I thought a bag of seed would go down well – Hayman’s this, Hayman’s that – he does so love plants.’

‘Won’t do,’ Salt said, and explained that not only had Lost Acre’s cultivars all proved barren, but none had lasted beyond a single season. ‘I’ve cleared them all – turned over “a new leaf”,’ he murmured. ‘Dust to dust.’ He paused. ‘What’s his tower like in daytime?’

‘You know the period: high windows, gloomy, scattered pools of light.’

A flicker of affection lit up Salt’s face. ‘I do have one survivor – and I’d like a good home for her.’ He finished the last of the Peculiar, smacking lips in appreciation, and took Ferdy back through the house to the front hall. Climbing over a trellis set against the wall was a thornless rose-like plant with pale green leaves and small crimson flowers, even now in October. To mark his return to normality Salt had removed the label.

‘Years old,’ said Salt. ‘Don’t ask me why she alone keeps going, because I have no idea. I call her the Darkness Rose. Evergreen, free-flowering, sweet-scented, and a creature of shadow.’

Ferdy smiled. Ferensen might see a gaudy pot plant as a rebuke to his natural melancholy, but this retiring beauty would surely cheer him up. ‘I’ll say it’s from all of us.’

Salt bagged up the rose and heaved a sigh of relief as the door closed on her. He and Lost Acre had parted company. There was no going back.

*

‘Ferensen?’ he called, but there was no response. The evening sun heightened the orange-pink of the Jacobean brickwork as he tried the door. Unlocked. At first he could not see Ferensen – the single octagonal room had returned to its original configuration, but with a marked difference: a solitary candle sputtering in the dampness barely illuminated the glass tanks trailing weeds that now lined the walls and the reeds growing in brass buckets. He had entered an aquarium.

‘Does the coolness bother you?’

Ferdy tracked the voice to the far corner.

Ferensen was sitting beneath a shelf cleared of books, away from the candle. Green fronds trailing from a long rectangular tank ran slick across his cheeks and head.

‘Are you all right?’

‘I’m laying up.’ His words bubbled.

Ferdy brought over the candle. Ferensen’s eyes looked glassy.

‘I’ve brought a thank you from all of us.’

Ferensen’s right arm snaked out and caressed the petals and leaves. ‘A plant of shade. Of hu—’ Ferensen briefly lost the word. ‘—midity,’ he finally added.

‘Salt calls it the Darkness Rose.’

‘Ah, yes, Salt – one of us now.’

‘I hope you like it.’

Momentarily the stems appeared to caress Ferensen’s fingers, rather than the other way round. A semblance of normality returned to his voice, although the sentences still grew, word by word, like a child piling building bricks.

‘Yes, I do, I do very much, and well named, so well named. Thank them – thank them all. Thank them all warmly.’

‘Thank you,’ replied Ferdy.

Ferensen raised his other hand in farewell. Ferdy placed the Darkness Rose on the floor beside the old man and withdrew.

As he descended the meadow to his home, he shook his head. If, God forbid, Bole made a move, Ferensen, their one-time leader and talisman, was in no fit state to oppose him; and Hayman Salt, who knew Lost Acre best, had hung up his boots.

Who was there to step into the breach?

*

Jonah Oblong, the School Historian and Rotherweird’s one officially recognised outsider, judged himself ‘acclimatised’ as a person and ‘arrived’ as a personality. He knew the rickshaws to avoid and the best baker. He had grasped the rudiments of the town’s circulatory system. He was even acknowledged in the street. His roots might be shallow, but at least he belonged.

Yet the excitement of his first six months, ending with the Midsummer Fair and Ferensen’s feast, subsided as the leaves lost their lustre. Familiarity had not bred contempt, more a coasting approach: no strain on the tiller. Life was comfortable, pleasant and, yes, increasingly familiar.

Another symptom nettled: his poetry had been afflicted by cosiness. The inner voice lacked edge. Deeper down lurked another fault-line. In that frantic summer he had engaged with Miss Trimble, Vixen Valourhand and Orelia Roc; now he languished alone.

These cross-currents had an odd effect. Oblong found himself half-hoping that Calx Bole’s manoeuvring presaged an outcome which nobody with an ounce of morality or sense would wish for: Geryon Wynter’s threatened return.

He felt an urge to test the historical evidence – the arms of the Eleusians known as The Dark Devices, the account of Wynter’s trial and the testimony gathered in advance of it – all held in Rotherweird’s sole place of record, Escutcheon Place.

But its guardian, the Herald, Marmion Finch, never entertained visitors, so Oblong sent a letter, which might have been better expressed.

Dear Mr Finch,

You may recall a certain dinner with a certain person, at which we discussed whether a certain other person might return. I feel the historian’s art would elucidate. I am free most afternoons in the week and most weekends and would be happy to work at Escutcheon Place.

Yours most sincerely,

Jonah Oblong

Finch’s reply had been terse, even rude:

Too many cooks. F.

PS Careless words cost lives.

The reply hurt, but worse, Oblong felt becalmed.

*

If Oblong hankered for flirtation, Orelia Roc craved passion. To compensate for its absence, she invested her energies in Baubles & Relics. Every week she travelled outside Rotherweird, indulging Mrs Snorkel’s penchant for blue-and-white pottery in return for permission to roam wider England, although her acquisitions were limited by the History Regulations and what she could carry. Orelia was convinced that Calx Bole had not been sated by the restoration of Lost Acre and Sir Veronal’s destruction – she and Ferensen had been at the mixing-point that Midsummer Day, powerless prisoners, and Ferox-alias-Bole could have killed them whenever he wanted. Bole was not a man of mercy, so he must be playing a longer game in which she remained an active piece.

2

Deathbed

Beneath a formidable exterior, Angela Trimble, Rotherweird School’s porter, had a sensitive side, which now prompted a restraining finger. ‘I prefer the candle.’

The doctor, privately dismissing the sentiment that soft light could ease a man’s passing and irked by an instruction from someone so low in the school hierarchy, nonetheless withdrew his hand from the gaslight. He cut a conservative figure in his three-piece suit, dark blue overcoat, brogues polished to a shine and a Gladstone bag.

‘You a minister?’ he asked drily.

Trimble read the subtext: why her, and not Matron? ‘He foresaw his decline,’ she explained. ‘He called it “nature’s way”. He asked me to help.’

‘You have professional staff.’

‘And their diagnosis was “no diagnosis”.’

The doctor did not share his puzzlement with Miss Trimble. ‘Tell me about the relapse,’ he asked.

A week earlier Vesey Bolitho, founder of the Astronomy Faculty and mixologist extraordinaire, had been his usual irrepressible self. Whatever the mysterious illness, he had appeared to be in remission, his pulse stronger, his colour restored.

She explained, ‘Two days ago he retired to his bed. He weakened physically, but sharpened mentally. Yesterday he wrote the inscription for his gravestone and made dispositions for his funeral. This morning he gave me a hug and closed his eyes. He’s remained mute and motionless ever since – which is not his usual state.’

The doctor held Bolitho’s wrist and found a barely discernible pulse. ‘Any time now,’ he agreed. ‘The body is closing down. I’d offer morphine, but he seems strangely . . .’

‘Content,’ she agreed. Content with leaving us, she thought. Why doesn’t he fight?

‘Should anyone be here?’

Again that unspoken message: the School Porter wasn’t a suitable companion for a head of department on his deathbed. But she knew the school’s web of personal relationships better than anyone – all human traffic docked at the porter’s lodge: teachers, pupils, cleaners, gardeners. Bolitho was loved by everyone, but an intimate of few, so candidates for this final vigil did not spring readily to mind.

The enigmatic Gregorius Jones she vetoed as incapable of seriousness, and half in love with him, she could not face the complications. She had seen Valourhand grow close to the professor, despite the traditional rivalry between North and South Towers, but she had disappeared on sabbatical. Rhombus Smith, engulfed by the paper sea that preceded every new term, had already visited earlier in the day. Orelia Roc had her shop to manage, Boris would be on a charabanc run, Gorhambury would be embroiled in municipal business and Fanguin would drink.

She shrugged her shoulders.

‘I’m sorry,’ added the doctor before leaving. He had never removed his coat. It was that hopeless.

After showing him out, she sat beside the bed and opened

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...