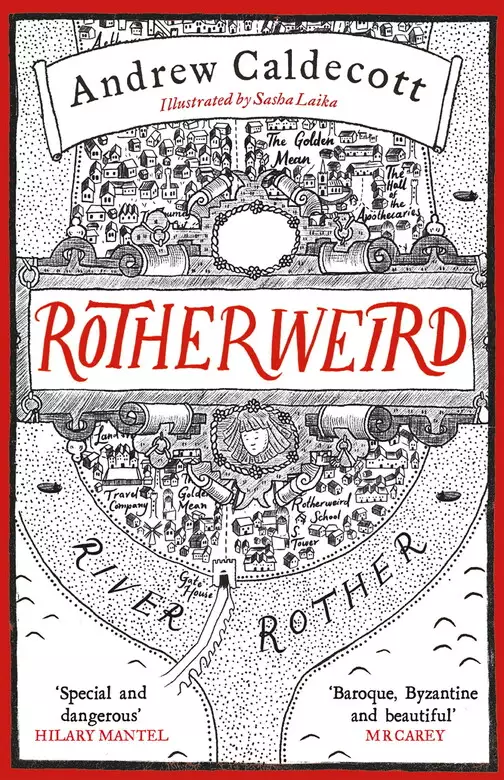

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Cast adrift from the rest of England, nobody studies the town of Rotherweird or its history. For beneath the enchanting surface lurks a dark secret. Two inquisitive outsiders have arrived: Modern history teacher, Jonah Oblong and the sinister billionaire, Sir Veronal Slickstone. Though driven by conflicting motives, both strive to connect past and present, until they and their allies are drawn into a race against time and each other.

Release date: April 25, 2017

Publisher: Jo Fletcher Books

Print pages: 510

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Rotherweird

Andrew Caldecott

February 1558. St James’s Palace, London.

One for sorrow: Mary Tudor, a magpie queen – dress black, face chill white, pearls hanging in her hair like teardrops – stands in the pose of a woman with child, her right palm flat across her swollen belly. She knows that what she carries is dead, if ever a baby at all.

‘This cannot be true.’

On the polished table lies a single parchment, a summary by her private secretary of ten reports from different corners of the realm. A courtier lurks in the darkness, faceless, a smudge of lace and velvet. The palace has the atmosphere of a morgue.

‘I have seen the reports myself, your Majesty.’

‘You think them cause for celebration?’

‘English boys . . . English girls. We are blessed with a golden generation.’

‘All born within days of each other – you do not think that a matter for concern?’

‘Some say it is a matter for wonder, your Majesty.’

‘They are the Devil’s spawn.’

Unnatural creatures, she thinks, sent to mock her barren state and sap her faith, their gifts in science, philosophy, alchemy and mathematics grotesquely developed for minds so young. Prodigies – such an ugly word. She glances down the unfamiliar names: seven boys, three girls.

‘Place them where they can do no harm,’ she adds.

‘Your Majesty.’

‘Find us an unforgiving island and maroon them there. They may not be taught or cosseted.’

‘Your Majesty.’

The courtier withdraws. He knows the queen is dying; he knows from the ladies of the Privy Chamber that the pregnancy is false. He must find a sanctuary where these children can learn and mature beyond the jealous royal gaze. He will talk to Sir Robert Oxenbridge, a man of the world and Constable of the Tower of London, where the gifted children are presently held.

He scuttles down the dim corridors like a rat after cheese.

*

Sir Robert watches the children playing on the grass near their billet in the Lanthorne Tower, and then surveys the strange miscellany of objects gathered from their rooms – abaci, sketches of fantastical machines, diagrams of celestial movement, books beyond the understanding of most of his adult prisoners, let alone these twelve-year-olds, and two wooden discs joined by an axle wound around with string.

The Yeoman Warder picks up this last object. ‘Designed by one of the girls. It’s a merry conceit, but requires much practice.’ He raises his wrist and lowers it in a languid movement and the conjoined discs miraculously climb and sink, higher each time, until they touch his fingers.

Sir Robert tries, but under his inexpert guidance the wooden wheels jiggle at the end of the string and stubbornly decline to rise. He is nonetheless captivated.

‘But there is this,’ adds the Yeoman Warder, holding out a board, on which are pinned the bodies of two bats, slit open to reveal their vital organs. Threads and tiny labels crisscross the corpses.

‘Not pretty, but then, the path of medical advancement rarely is,’ replies Sir Robert, without complete conviction.

‘He is different, Master Malise. Remember, one serpent in the Garden was enough.’ The Yeoman Warder points to the lawn below and Sir Robert sees the difference – the boy stands aloof, not from shyness but a natural arrogance.

He recalls the queen’s opinion that they are the Devil’s spawn, but the playful inventiveness of the discs-on-a-string decides him, and the thought that when the old queen passes, the new dispensation will not favour banishing talent on superstitious grounds. Sir Robert turns his mind to an old friend, Sir Henry Grassal, a kindly widower. He owns a manor house in one of England’s more secluded valleys and has the wealth, learning, time and inclination to provide the needed refuge and, no less important, the education.

As befits a veteran soldier, he plots a strategy. Even a sick queen has many eyes and ears.

April 1558. A wooded country lane.

It is early morning on an obscure tributary of the main highway. A covered wagon drawn by a single horse of no distinction appears, and stops. A ladder is lowered. Mud-stained urchins emerge, seven boys, three girls, and huddle on the roadway for warmth as broken sunlight knifes through the canopy. Each child clasps a silver penny bearing the faces of the queen and her foreign king and a lordly motto: PZMDG Rosa sine spina – Philip and Mary by the grace of God a rose without a thorn.

A second wagon appears, very different to the first. The slats on the side are polished to a shine, the wheels fortified with iron rims, the harnesses of finest leather tether four horses, not one. The wagon halts on the opposite side of the clearing and once again steps are lowered to deliver ten children – but these are mirror-opposites with clean complexions and clothes cut to fit. Like two teams from different worlds, haphazardly drawn together in the same game, they eye each other across the glade. Sir Robert points at one cart and then at the other, urging each group to cross. The children understand the instruction and its immediate purpose, although none can fathom the deeper reason for the switch.

This is not a mission for strangers. The carter fought with Sir Robert Oxenbridge in France and trusts his former captain in all things, but he has never heard children speak this way, exchanging complex chains of numbers and shapes with foreign names, even discussing the arrangement of the heavens. He crosses himself, uncertain whether his new charges are cursed or blessed.

Sir Robert, riding alongside, notes the gesture and its ambiguity. He still judges the children virtuous, save for the boy with the surgical interests, Master Malise – such joyless eyes.

They descend from the valley rim and Oxenbridge points far below. A single plume hangs in the air.

‘Rich man’s smoke,’ he says, knowing the difference from a campfire, ‘from the tallest chimney at Rotherweird Manor – our destination.’

He smiles at the carter. Had there ever been a gentler act of treason?

2

Second Interview – The Boy

The boy stood outside Vauxhall Station facing the bridge across an array of traffic lanes, pedestrian lights and bus stops. It was bitterly cold and still dark at 6.20 in the morning. He would be on time. He fingered the switchblade in his pocket. If the meet turned out to be some kind of pervert, he would pay.

Ignoring the underpass, he vaulted the railings instead. A young suit stumbled towards the station, looking the worse for wear. Noting the bulge in his jacket pocket, he toyed with taking him, but decided against. He was off his patch, and alone.

The hand-drawn map directed him to the riverside flats west of the bridge with the instruction ‘Press P’ at the point of arrival. He peered up – posh, real posh. The boy feared that ‘P’ meant parking, having no intention of getting into a stranger’s car, but this ‘P’ sat on top of the row of silver buttons. Anxiety turned to excitement. He smelled opportunity. Someone rich was looking his way. The world might label him a victim of his background, but he was not a victim of anyone or anything; he was himself, a force, going places. But the tag did have its uses: here was another fool, determined to cure him.

He pressed the button and a smooth voice spoke from the grille: ‘Go to the lift. Press “P” again.’

The door clicked open. Where the boy came from, lifts were rare and never worked when you found them. They were places for meets and dealing and graffiti. This lift had a carpet that swallowed your shoes, and cut-glass mirrors. The ascent was silent, its movement undetectable as the numbers beside the door flared and faded.

The boy walked into a lobby and gawped at the stunning view, sallow light staining the river as the city began to stir. There were more cars now, and the occasional bicycle. Above the table in front of him hung a picture of the same river in evening light with a small brass plate – Monet 1901. Beneath it a bronze frog stared straight ahead.

The boy was right to be apprehensive. He had been watched. The tall man bent over the telescope had fair, almost albino skin, close-cropped silver hair and a high forehead. The lines in his face were fine, as if age had been kept at bay by some rarefied treatment. His hands were long, almost skeletal, the fingernails manicured. His Indian-style jacket, dark trousers and open-necked silk shirt mirrored the easy elegance of his penthouse flat. The boy did not know it, but he had chosen the art and furniture himself; he frowned on wealthy men who used advisors for taste.

He polished the telescope lens, replaced the cap and turned to the internal cameras. The boy was crude, but build and face held promise. He pressed the internal intercom: ‘Bring him in – and remove the knife.’

The boy was disarmed by a young man with a minimum of fuss; he knew when not to mix it up. He was ushered into an office with computers standing in ranks on a glass table on one side of the room. In company with the modern were artefacts and pictures that meant nothing to him, except that they screamed ‘money’. His host sprang from an armchair and the boy revised his expectations: this was no do-gooder. The lips had a heartless curl to them.

Unsettled, he sought to assert himself. ‘What am I ’ere for?’ He was used to staring people out – barristers, magistrates, child psychiatrists, social workers, policemen, rivals on his patch – but he evaded these remorseless eyes. Worse, the man did not speak. The boy was used to dealing with people who came to the point – twenty quid, two kilos, guilty or not guilty, who to cut; business talk.

When it did emerge, the voice was as firm as the handshake. ‘A drink, perhaps?’

‘I’m not ’ere for a drink.’

‘Coffee for me,’ said the old man, ‘medium sweet. And macaroons for our friend – with nothing to drink.’ The assistant left the room. ‘I appreciate your coming,’ continued the man.

‘My coming for what?’

‘Do sit down.’

The boy did so, noticing that each chair arm ended in a predatory animal’s head.

The man searched his face before offering a hint of a smile, apparently satisfied. ‘What are you here for? A fair question. Call it a role more than a task.’

The boy hated smart talk. His nostrils twitched at the mild oily fragrance to the old man’s hair.

‘You play a part – understand?’

‘I dunno what you’re on about.’

The man held up a list of the boy’s convictions – Court, date, offence and sentence. ‘Impersonation, forgery, obtaining money by deception . . .’ The list covered several pages – an unedifying mix of dishonesty and violence.

The boy played the victim card. ‘Things have been ’ard. ’ad no chance, did I?’

‘You had plenty of chances. You just got caught.’

Now the boy knew he was here to be used, not cured. ‘Whaddya want, then?’

‘I have lost something rare and valuable. You need only know it was taken from me long ago.’

‘Then you gotta pay.’

‘I haven’t got to do anything.’

The assistant entered with a tray and the fragrance of fresh baked macaroons permeated the room. The boy grabbed one. His host followed, picking up his with a slow, easy elegance.

‘If I get no money—’ interrupted the boy, his mouth half full.

The old man sipped his coffee, quite unhurried. ‘You reject my terms before you’ve heard them?’

The boy bit his lip. ‘’ow much then?’ he asked.

‘Enough for a son of mine.’

Son of mine! An expletive died in the boy’s throat. Perhaps, after all . . .

‘’ow much is that?’

‘Think thousands.’

A posh phrase came to him: son and heir. ‘You got other kids?’

‘My wife and I are, regrettably, not blessed.’

So he wanted a son – but why choose him? ‘What about my probation officer?’

‘The adoption papers are ready. You have only to sign.’

‘All this to find – what?’

The old man ignored the question. ‘You will be transformed – new name, new clothes, new voice.’

From his host saying nothing of substance, the conversation was now moving alarmingly fast. ‘What if I refuse?’

‘Make that choice and you’ll find out.’

‘We’d be staying ’ere?’

‘For a month or two, while we polish you up, then to a country town. You’ve never been to the country. Experience is a form of power, Rodney.’

‘Rodney?’

‘“Rodney” suits him, don’t you think?’ the old man said to the assistant, adding, ‘With work.’

‘Yes, indeed, Sir Veronal,’ the assistant agreed.

Sir, Sir Veronal – the boy had never met a ‘sir’ before, nor indeed a ‘Veronal’.

‘Why are you doing this?’ asked the boy.

‘I’m a philanthropist,’ explained Sir Veronal. ‘I give.’

Not without taking, thought the boy.

‘And when I make generous offers, I like an answer.’

The offer was a no-brainer, but the boy’s desire to win ran deep. ‘You might be on, if you tell me what I’m looking for.’

The lines on Sir Veronal’s face fleetingly looked like scars. ‘It’s something you’ll always have, even when it’s gone. Mine was stolen.’ Sir Veronal rose to his feet. ‘Naturally, there are conditions. Violence is usually an admission of failure. As they say on the medicine bottle: use only as instructed. And remember, I hire you to listen – in school, in the street, wherever.’

‘School—?’

‘Children know more than adults think, but they lack discretion.’ Sir Veronal smiled; discretion was too rich a word for the boy in his present state. ‘Meaning, when to keep their mouths shut. You must become adept at worming your way in.’

A beautiful woman glided into the room, tall, middle-aged, with marble-white skin and dark hair held back by a golden slide. Her eyes had a striking tint of violet, and she had a way of standing as if she had practised the pose for maximum elegance.

She spoke quietly, but with a penetrating clarity. ‘Welcome home, Rodney.’

‘Lady Imogen,’ explained Sir Veronal.

Rodney held out a tentative hand as Sir Veronal allowed himself another smile. The unruly colt was broken.

‘We want an English boy of breeding, style without ostentation. First we clothe you properly. Then we start on that voice.’

The boy nodded obligingly. His benefactors were clearly mad, and there for the taking. Play along, he said to himself, just play along.

3

Third Interview – The Teacher

Jonah Oblong’s career as history teacher at Moss Lane Comprehensive – his first post – was dramatic, but short. When asked about his predecessor, the Head had looked at his shoes and muttered, ‘Fled to Australia.’

Oblong soon understood why. The class boasted seven different first languages, three intimidating bullies and four pupils with parents hostile to the idea of their offspring learning anything they did not know themselves.

Then there was the problem of Oblong’s appearance, which lay not in the face, which was pleasing enough, but in the bandyness of his legs and their disproportionate length. With the gangly build came clumsiness, an attribute that, whilst endearing in other contexts, did not assist in the pursuit of class discipline.

Oblong began well – his re-creation of the Great Fire of 1666 with a cardboard city in the school car park achieved a hitherto unknown interest in England’s remote past – but the mantle soon slipped. His division of the class into Roundheads and Cavaliers led to two broken windows, and a King Canute demonstration caused a flood.

Conventional methods fared no better. After three minutes beside the blackboard, Conway, head of the Wyvern Shanks gang and no respecter of authority other than his own, interrupted. ‘Can’t we do the World Cup?’

‘It’s not history.’

‘Why not?’

‘It hasn’t happened yet.’

‘What about the last one?’

‘Bor–ring,’ whined two girls at the front.

‘It’s not on the syllabus.’

‘He don’t know,’ crowed Conway, ‘Ob-bog don’t know who won.’

‘Brazil . . . ?’ guessed Oblong.

Guffaws all round.

Conway’s water bomb hit Oblong on the shoulder, and something snapped in that gentle psyche. Oblong took the plastic water jug from his desk and poured the contents over Conway’s head, just as the School Inspector walked in. Sensing his fate, the class behaved faultlessly for the rest of the lesson and said ‘sorry’ (in so many words) at the end – even Conway.

At the Employment Exchange, he was labelled overqualified or underqualified for every vacancy except teaching, where the lack of a single reference was proving fatal. The woman behind the counter handed him a dog-eared copy of the Times Educational Supplement, adding with a wan smile, ‘You never know.’

He invested two pounds from his diminishing reserves in a small cappuccino and went to the local park. The TES revealed a demand for scientists and an even greater demand for references. He persevered to the last page of the classifieds, where a square edged in black like a funeral notice advertised the following: ROTHERWEIRD SCHOOL – History teacher wanted – modern ONLY – CV, photograph, no references.

Like everyone else, Oblong had heard of the Rotherweird Valley and its town of the same name, which by some quirk of history were self-governing – no MP and no bishop, only a mayor. He knew too that Rotherweird had a legendary hostility to admitting the outside world: no guidebook recommended a visit; the County History was silent about the place. So: a hoax more likely than not, Oblong concluded.

Nonetheless, he sent in his application that morning, declaring a desire ‘to share with my charges all things modern and nothing fusty and old’.

To his astonishment a reply came back by return:

Dear Mr Oblong,

We are impressed by your credentials and priorities. Present yourself for interview in the New Year, 4.pm., 2nd January (pre-term, quiet). Train to Hoy; thereafter a test of your initiative.

Yours most sincerely,

Angela Trimble, School Porter

He checked the trains online and found Hoy well served. The station was unexpectedly quaint, with a lovingly preserved clapperboard signal box. Oblong hailed a taxi.

‘Rotherweird don’t do cars,’ responded the taxi driver with a toothless smile.

‘I’ve an interview at four.’

‘In Rotherweird? Who are you – the Archangel Gabriel?’

‘I’m a teacher.’

‘Of what?’

‘History.’

The taxi driver looked amused. ‘Take a bus to the Twelve-Mile post and then the charabanc.’

‘Why can’t I take a taxi?’

‘The charabanc meets the bus; it don’t meet any taxi. Sorry, mate, Rotherweird isn’t like other places. Bus stop over there.’

The bus stop sign had a separate plate beneath the more conventional destinations: Rotherweird bus for charabanc, according to need. The bus – an old Volkswagen camper van – arrived minutes later.

‘You coming or what?’ the driver shouted rudely out of the window. Oblong clambered in.

The van hastened through rolling hills and farmland until, spluttering after an extended climb, it reached a huge spreading oak. Oblong looked round. He could see nothing of note. The driver jabbed a finger in the tree’s direction.

‘That’s the Twelve-Mile post, that’s the Rotherweird Valley, and you owe me six quid.’

Oblong paid up. The camper van disappeared in a belch of smoke back the way it had come.

At all points of the compass, hills basked in midwinter sunshine, yet the valley below lay hidden in fog. He was standing on the rim of a giant cauldron in which, somewhere, lurked Rotherweird, and an interview. He found it curious that a place so determined to resist modern transport should insist on a modern historian. He heard a whirring noise, followed by a disembodied voice – a deep, cavernous bass – and snatches of the song it was singing:

‘Not all those who wear velvet are good,

My child,

Beware those who like silver, not wood,

My child . . .’

Out of the mist lurched an extraordinary vehicle, part bicycle, part charabanc, propelled by pedals, pistons and interconnecting drums. The double bench in the back had a folded canvas hood for protection. The driver wore goggles, which concealed his face but not a shock of flame-red hair. On the side of the charabanc, written in florid green and gold, stretched the words: The Polk Land & Water Company and underneath in smaller letters: Proprietors: B Polk (land) and B Polk (water).

‘That’s the Twelve-Mile post, that’s the Rotherweird Valley, and you owe me six quid.’

Smoothing greasy fingers down the front of a grease-stained shirt, the driver introduced himself as Boris Polk. ‘Seven minutes late – my apologies – damp plugs and visibility nil.’

‘It’s only that it’s gone three and—’

‘Time equals distance over speed. I’m not to be confused with Bert – we’re identical, but he’s first by five minutes. I invent and he administers; he has children, I do not; I chose land and he chose water, which is interesting, ’cos—’

‘I’ve an interview – my only interview—’

‘Interview!’ exclaimed Boris, raising his goggles to examine his passenger more closely. ‘I haven’t had one of those since the summer of . . . the wet one, now when was that . . . ?’

‘It’s at four.’ Oblong pointed at his watch for emphasis. ‘Four, Mr Polk, that’s less than an hour away.’

‘Is it now? “Time equals distance over speed” is another way of saying there isn’t goin’ to be no distance – not with you standing there like a totem pole – because there isn’t goin’ to be no speed.’

Chastened, Mr Oblong heaved his case into the back and was about to follow it when Boris resumed, ‘My dear fellow, you’re a co-driver, not a fare. We don’t waste energy at The Polk Land & Water Company. Pedal like the clappers, and she goes like the clappers.’

‘Right,’ said Oblong.

‘My patented vacuum system creates thrust – without engine noise, please note – so energising the lateral coils, and—’

‘Hadn’t we better—?’

‘Avanti!’

The dominant Oblong gene was a tranquil one, as attested to by an ancestry of minor diplomats (the sort who write out table plans in copperplate writing, but make no decisions of moment). However a rogue chromosome occasionally surfaced, as in One Lobe Oblong, a pirate hung by the French in the 1760s. And now a deep-buried wish for adventure stirred in One Lobe’s descendant, encouraged by the breakneck speed, the wheeze and whoosh of the vacuum system and Boris’ penchant for taking bends on two wheels rather than four. The fog enhanced the feel of a fairground ride, briefly thinning to reveal the view before closing again. In those snapshots, Oblong glimpsed hedgerows and orchards, even a row of vines – and at one spectacular moment, a vision of a walled town, a forest of towers in all shapes and sizes, encircled by a river.

The light was failing fast when the charabanc finally lurched to a halt. Fog swirled like smoke from the river below.

‘Old Man Rother,’ explained Boris.

A bridge reared disconcertingly into the dark, at right angles to the town, to judge from the yellow smudges of lit windows.

Oblong clambered out. ‘What do I owe you?’

‘Nothing, and good luck, and be yourself.’

He added a cheery wave as Oblong set off up the slope of the bridge, cobbles turning the arches of his feet. Mythical stone birds and animals stared down from the parapet. At its summit, the bridge curved sharp left and descended to a forbidding gatehouse, its portcullis lowered. Rotherweird Town had been built to keep its enemies out – or its inhabitants in.

He shouted and waved his arms until, with much clanking, the portcullis withdrew into the battlements. Through the open arch a broad street ran north, signed the Golden Mean.

A statuesque blonde sat on a wooden bench by the gatehouse wall, improbably reading by a gaslight on an elegant hook above her head. She stood up. Mid-thirties, Oblong thought, and not to be trifled with.

‘I suppose you’re Jonah Oblong.’ The voice was deep, the tone no-nonsense.

‘You must be Angela, the School Porter,’ guessed Oblong.

‘Miss Trimble to you.’ She added, ‘Horrible evening!’ as if he were responsible.

Oblong heard a violin, faint but distinct, practising a daunting run of arpeggios with aplomb.

‘Strong on music,’ he said, to win her round.

‘Strong on everything – this is Rotherweird, you know.’

Oblong glanced at his watch.

The gesture did not impress. ‘There’s modern history for you, always in a rush. Until you’re staff, you don’t go in – and you’re not staff until you’re hired.’ She opened the oak door behind her. ‘You’d do well to remember we’re most particular about history.’

She escorted Oblong into the Gatehouse and down a stone passage to a second oak door, reinforced with crossbeams and studded with rusty nails. She lifted the knocker, a grotesque face, and let it fall.

‘Do come in,’ said a reassuringly friendly voice.

A large table had been pushed against the near wall. A sentry-duty rota hung above it. Two ornate oak chairs faced him, probably imported for the occasion, judging by the dinginess of the rest of the décor. Both were occupied, one by a short, rotund man with small eyes and lank, dark hair; and the other by a tall angular man with a beaky face, a bald crown and bushy white eyebrows. The small man’s clothes were expensive; the tall man’s might have been so once, but were now beyond any respectable second-hand stall. Oblong sensed they did not like each other.

Facing the chairs was a stool. Oblong obeyed the small man’s instructions to sit. He felt like a man in the dock.

The tall man extended a hand and introduced the short one. ‘Mr Sidney Snorkel, our Mayor. He likes to participate in appointments. I am Rhombus Smith, Headmaster of Rotherweird School.’

‘We take the teaching of the young most seriously in this town,’ interjected Snorkel in an oily, sibilant voice. ‘We like our teachers focused. Chemists do not teach French. Sports masters do not dabble in geography. And modern historians—’

‘—keep to modern history,’ chipped in Oblong, remembering the advertisement.

‘In class and in life,’ said Snorkel, before embarking on a series of staccato questions: ‘Dependants?’

‘None.’

‘Hobbies?’

‘I write poetry.’

‘Not historical poetry?’

Oblong shook his head.

‘Published?’

‘Not yet.’

Snorkel nodded. Oblong’s literary failure to date was apparently a good thing.

‘It consumes all your spare time?’

Again Oblong nodded.

‘You realise you teach modern history and no other history whatsoever?’

‘Keep to the subject, I understand.’

‘Any questions for us?’ asked Smith politely.

‘Questions?’ echoed Snorkel, but impatiently, as though his mind were made up, despite the absence of any enquiry about Oblong’s gifts as a historian or a teacher (being, of course, two very different things).

Oblong asked about lodgings – rooms to himself, rent-free, with a cleaner thrown in. He asked about food – breakfast and lunch, also free. He asked about pay – generous, albeit in Rotherweird currency. He asked about dates.

Snorkel answered this question, as he had all the others. ‘Term starts in ten days – arrive four days early to settle in. You’ll be Form Master to Form IV and modern historian to all.’ Snorkel stood up. ‘He’ll do,’ he said, adding in Mr Oblong’s general direction, ‘Good evening – I’ve important guests for dinner.’

Miss Trimble entered, helped the Mayor into an immaculate camelhair overcoat and they both departed.

Rhombus Smith closed the door. ‘You can say “no”, but I’d rather you didn’t. Mr Snorkel is so very hard to please.’

‘I’ve not been interviewed by a mayor before.’

‘The price we pay for avoiding those idiots in Westminster.’

‘He interviews everyone?’

‘Oh, no. The modern historian is a political appointment.’

‘Sorry?’

‘Curiosity about the past is your game, but we’re forbidden to study old history – by law.’

‘Why?’

‘Ha, ha, that’s a good one – I’d have to study old history to find out, wouldn’t I! So just remember to keep it modern. 1800 and after is the rule, and never Rotherweird history, which incidentally you shouldn’t know anyway. Now, my boy, is it a yes – or do you need another five minutes to think about it?’

Oblong had no hint of a prospect anywhere else, and he firmly believed in the old adage that a good headmaster never runs a bad school. He accepted.

‘Splendido!’ exclaimed Rhombus Smith, shaking his hand warmly. ‘My motto is, scientists teach while we in the arts civilise. Isn’t that right?’

Oblong nodded weakly as the Headmaster hunted through various pieces of furniture before retrieving two pewter tankards and a large bottle labelled Old Ferdy’s Feisty Peculiar. ‘Ghastly job, manning the Gatehouse. This keeps them sane.’

The beer was indeed memorable: earthy, the taste layered. Rhombus Smith raised his tankard by way of a toast. ‘To your happy future at Rotherweird School.’

‘My . . . happy . . . future,’ parroted Oblong without conviction.

The Headmaster opened a window and peered out. Through his fertile mind, courtesy of an eccentric but photographic memory, flashed several obscure literary passages descriptive of fog. ‘Who’s your favourite weather author?’ he asked, closing the window.

‘Shakespeare.’

‘Myself

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...