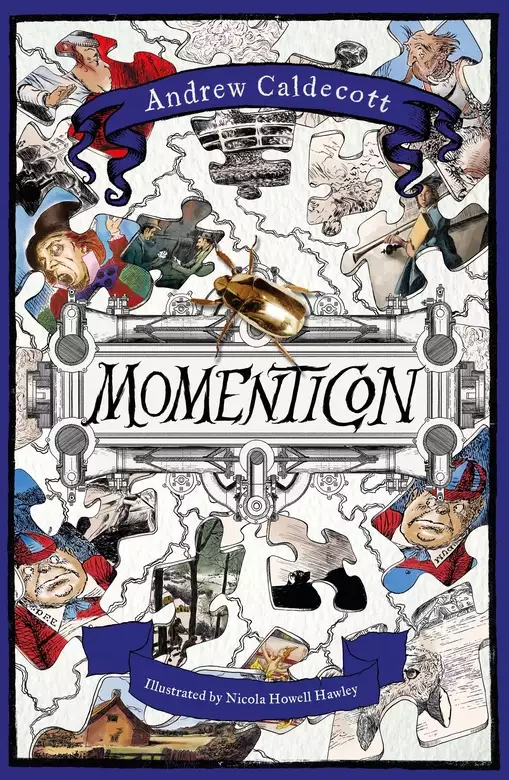

Momenticon

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

A hugely compelling, dark, offbeat adventure from the bestselling author of ROTHERWEIRD.

'A deeply strange but also deeply compelling world' Blue Book Balloon

The world has become a dangerous place: the atmosphere has turned toxic, destroying almost all life, and most of humanity too.

Survivors live in domes protected by chitin shields, serving one or other of the last two great companies. A long period of uneasy collaboration between Tempestas and Genrich is about to end, and they have very different visions for mankind's future.

Far from these centres of power stands the Museum Dome, home to mankind's finest paintings and artefacts and their curator, a young man, Fogg, who has laboured for three years without a single visitor.

Then a single mysterious pill - a momenticon - appears in the Museum and triggers a series of bewildering events, embroiling Fogg and his unexpected new companions in a desperate fight against the dark forces which threaten to overwhelm all that remains.

And time is running out.

'Compelling and enrapturing . . . captures the reader from the first page to the last. A five-star read' Grimdark Magazine

'One of the UK's most intriguing imaginations. Momenticon is whimsical science fiction at its finest' Geek Dad

Release date: May 12, 2022

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 480

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Momenticon

Andrew Caldecott

Author’s Note

Paintings and artefacts from the Museum Dome feature in this story in unconventional ways. They appear below in order of appearance, with their and their creators’ old-world dates and the old-world places from where they were retrieved. The reader will recognise fragments of some from the cover and in Nicola’s delightful drawings.

Wheatfield with Crows (1890): by Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890), Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

The Water-Lily Pond with the Japanese Bridge (1899): by Claude Monet (1840–1926), The National Gallery, London.

The Death of Marat (1793) by Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825), Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Brussels.

The Art of Painting (1666–8): by Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675), Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There, (published 1871): illustrated by John Tenniel (1820–1914), original woodblocks in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

The Dog (1819–1823): by Francisco Goya (1746–1828), Museo del Prado, Madrid.

The Hunt in the Forest (c1470): by Paolo di Dono (known as Uccello, 1397–1475), Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

The Hunters in the Snow (1565): by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c1525–1569), Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

Winter Landscape with Skaters and a Bird Trap (1565): by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c1525–1569), the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels.

La Gare Saint-Lazare (1877): by Claude Monet (1840–1926), Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

Boulter’s Lock, Sunday Afternoon (1885–97): by Edward John Gregory (1850–1909), the Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight, the Wirral.

The Circus (1890–91): by Georges Seurat (1859–1891), Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

The Calling of Saint Matthew (1660): by Michele Angelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571–1610), San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome.

A Cottage in a Cornfield (1817): by John Constable (1776–1837), National Museum Cardiff, Cardiff.

The Garden of Earthly Delights (right-hand panel of the triptych, detail, 1490–1510): by Hieronymus Bosch (c1450–1516), Museo del Prado, Madrid.

The Card Players (1892–6): by Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), The Courtauld, London.

Totem-pole from Haida Village, cedar wood, British Museum, London.

The Uxe totem-pole, provenance and wood unknown.

1

Fogg

Dead centre on the Biedermeier table below Monet’s lilies (a 1919 version, painting no. 184) lay a largish white pill stamped with a pink sickle moon and an amber star. Fogg picked it up. Who had put it there? What did it do? He peered up at the ceiling, whose erratic pattern of metal joists and panels looked unchanged. Anyway, pills don’t drop from ceilings.

The pill looked at him, and he looked at the pill. Dare you, whispered the pill.

He carried it down to Reception and examined it through his magnifying glass. An ordinary pill, but for the weight and the mysterious markings. He reflected on the coming anniversary and the lack of incident in the Museum’s last three years. Wherever it had come from, whatever it did, surely the pill was meant for him.

But might it be poison? Was his position as Curator about to be terminated by some unseen governing presence?

He weighed the evidence. Behind Reception in the Museum Dome a small screen displayed a message with a sting in the tail:

Time since Opening: 2:364:09:54

Visitors: 0

Tomorrow would be the third anniversary of his arrival at this last repository for Man’s most treasured artefacts, but it had never had a visitor and he had never delivered his over-rehearsed opening spiel to anyone. More to the point, there had been no hint of his being watched or assessed. Nor could any fair person hold him responsible for the dearth of visitors.

Outside, toxic ochre dust swirled and settled as it always did. Without the chitin shield, the Dome would have disintegrated, just as the world’s cities had at the Fall. There was no play of light, or even a visible sky, for the Earth’s private star had long been banished from view. The Dome was an ark and the paintings its cargo, even if this Noah had neither crew nor family.

Nor, he reflected, had he transgressed. His regime had been orderly to a fault.

Today, like every other day, he had completed his exercise routine in the anteroom between his bedroom and the Museum proper on the dot of eight o’clock. He had hurried through a breakfast of bland but nutritious paste from the Matter-Rearranger and completed his ablutions by 9.30 precisely. Thence to the daily robing which justified his unique existence: the donning of the Curator’s uniform. He had smoothed the dark flannels over his thighs, straightened any threat of a crease in the cream shirt and stretched his arms through the sleeves of the pièce de résistance: the dark green jacket with brown piping, the material more velvet than cloth. He had straightened the tie, checked the gleaming toecaps of the black, laced brogues and combed his thatch of straw-coloured hair before adding the Curator’s cap.

So far, so good.

But one troubling piece of evidence nagged away. Fogg had an eye like a spirit level and that morning Van Gogh’s Wheatfield with Crows (painting number 211) had been out of true.

The Museum Dome gave access to its many wonders by an Escher-like maze of escalators, landings and walkways. Each escalator moved as a foot landed and halted when there was no weight left to carry. They shut down after hours. Energy conservation must have been a priority in the last days. Every escalator ascended, save for the topmost, which twisted from the final landing around a central support like a helter-skelter. You had to travel through the whole Museum in order to leave.

On his first days here, Fogg, still just shy of his twentieth birthday, had devised a route which passed every exhibit once and no exhibit twice. He had never deviated since. The hanging had been done before his arrival by persons unknown, but he liked the idiosyncratic mix of time and subject. Wooden furniture stood beneath modern abstracts; Old Masters hung over steel and glass; two totem-poles rose from floor level. Fogg ensured that every item was always in perfect alignment in itself and with its neighbours. He abhorred deviation.

One of the two totem-poles had a tendency to bleed dust from time to time, which he instantly cleared. He abhorred untidiness too.

The previous evening Wheatfield with Crows had shown no sign of misbehaviour. He wondered if a floor beam had shifted in the night, but the mainframe said otherwise.

An inexplicable knock, and an inexplicable pill.

What the hell.

He drew a glass of water from the Matter-Rearranger and downed the pill.

His surroundings vanished. He was facing a white-painted footbridge which curved over an expanse of real, unpolluted water. Twin rails supported a pergola smothered in spikes of purple flowers.

Fogg had never seen real vegetation, let alone blossom. He had never heard Nature’s music. Whether these mysterious sounds were the calls of birds or frogs or some other creature, he could not tell. He stood beside the artist, unnoticed, and by some miracle shared the old man’s thoughts.

Waterlilies are a special pleasure. They float, detached from the common silt of experience, and their explosions of colour – cream, carmine, pink and yellow – shimmer and reflect in an ever-changing light show. Lilies open; lilies close; the surface of the water plays to the wind and the light cools, burns, fades, intensifies. Clouds burgeon and dissipate.

Fogg was so rapt in this borrowed experience, joining another man in an era before the Fall, that it took time for him to register that the painting taking shape in front of him was now in his Museum.

As recognition dawned, the scene melted, colours running as if sluiced in white spirit; and he was back. The experience had brutally exposed his present surroundings as silent and drab; natural colours surpassed the richest any of his paintings could offer. Worse still, the old man had tantalised with the prospect of human company. Three years and no visitors! He must be the last man standing.

Only then did the most significant fact strike home: the pill had been placed beneath the very painting whose world it had opened up. That had to be design, not accident.

He rushed round the Museum, hoping to find another, to no avail. To date Fogg had faced only the puzzles which the exhibits themselves presented. The mainframe carried out the menial roles – lighting, waste disposal, escalators, heating – and the Matter-Rearranger provided nutrition and beverage. Neither made pills. He toyed with various explanations. The pill had been a hallucinogen, or an educational device. Perhaps one would appear each day beside a different picture. The other possibility, that he really had been drawn into the very moment of painting, he dismissed as absurd.

As his rituals resumed, anxiety eased. Copying from memory with faultless accuracy was his particular gift. He spent every afternoon seated at Reception, reproducing as a drawing one of the Museum’s paintings. At six, he downed his pen and checked the readings for humidity, toxicity and moisture. He found nothing untoward.

By then the shimmer-light, as he called it, had faded to blackness. Beyond and above, nine thousand stars, once visible to the naked eye, looked down.

His evening patrol yielded no more surprises.

He discussed his nightcap with the Matter-Rearranger.

‘What flavour tonight, sir?’

‘Give it a kick.’

‘Cocktails, sir, are not in the repertoire.’

‘A pretend kick at least.’

‘Chocolate with an undercurrent of lemon, perhaps?’

‘Go for it.’

He yearned for a book, but the Museum had only tour programmes, all of which he knew inside out.

As a poor substitute, every night he told his invisible physical trainer, AIPT*, a bedtime story, starting always from an exhibit. Over time, he had become more adventurous, even matching voice to character. AIPT had qualities: basic speech, eight varied programmes and a camera which caught all imperfections. However, it had no grasp of the narrative arts.

‘Tonight, we have a story of a man murdered in his bath.’

‘Your shoulders are lopsided.’

‘He has, however, ordered the deaths of many people. He—’

‘You should speak from your diaphragm, not your throat.’

‘He is lying back with quill and paper when a young woman enters.’ Fogg’s voice rises an octave. ‘“Monsieur Marat,” she says—’

‘Keep that jaw perpendicular.’

And so on – but it is dialogue, of a kind.

Then to bed, where the usual questions bubbled up: who delivered him here, and why? To gather such a collection and build such a Dome required resources and vision. He knew of only two organisations with the wherewithal – Genrich, all science and no art, and Tempestas, which liberally displayed its corporate emblem, a fist clasping a bolt of lightning, wherever it held sway. But it did not feature here, not at Reception, not on the Guides, not on his uniform.

After wrestling with these imponderables, he finally succumbed to a sleep laced with the day’s new experience: the scent of blossom and the call of birds.

Fogg awoke minutes before his alarm beeped, his metabolism conditioned by habit. He pushed aside the silvery bedspread as the tasteless beige curtain on the convex window slid open. He bowed to the window, arms akimbo. Deo gratias. He had lasted three whole years.

But had he? The screen beside his bed, which mirrored the one at Reception, had stalled:

Time since Opening: 3:000:00:00

Visitors: 0

He tapped the glass cover. He hit it with his shoe. Not a flicker of a response. The succession of noughts brought home three years of solitude. Had he achieved anything? What use is unshared knowledge?

As ever, he fell back on ritual.

He slipped into tracksuit bottoms, white ankle socks and a tatty T-shirt and joined AIPT in the anteroom.

‘Today we focus on hamstrings,’ droned AIPT, ‘tight hamstrings.’ AIPT raised the pain threshold slowly. ‘Squat . . . deep and slow . . . hips backwards . . . neutral spine . . . hold.’

‘You’re a machine. Why are the screens frozen?’

‘Uncurl the vertebrae, one by one. Without rush.’

‘Rush has no meaning – time has stopped. I’m asking you why.’

‘Knees to tabletop,’ replied AIPT, before adding, ‘Maybe, sir, it’s time to explore.’

Fogg tumbled backwards. Never, in three long years, had AIPT ever commented on anything other than posture, muscles and breathing. The voice had also changed, he was sure of it, acquiring the mildly ironic tone of a servant who knows more than his master.

‘You try bloody exploring out there.’

AIPT fleshed out his correction. ‘I suggest, sir, that three years without visitors isn’t good for a man.’

AIPT resumed its liturgy, closing with a familiar envoi: ‘Tomorrow we work on the pelvic floor.’

Then silence, the usual rest-of-the-day silence.

The morning proceeded in the same vein. A familiar ritual would commence without mishap, only to spring a nasty surprise.

The Matter-Rearranger delivered the conventional breakfast, until he entered the code for coffee, when it produced a virtual antique trumpet.

He passed a hand straight through it. A second attempt summoned a further trumpet, which blurred the outline of the first.

What was going on?

‘I did not order a trumpet,’ he said grumpily.

‘Maybe somebody else did,’ suggested the Rearranger.

‘Like who?’

‘Mr Vermeer, perhaps?’

Fogg gulped. A sustenance machine with a grasp of art history?

At least the remainder of his morning tour passed without incident.

Don’t be paranoid, he told himself. The malfunction which had afflicted the chronometer and AIPT must have struck the Rearranger too.

Then his cosy world fell in. At Reception, the green faux-leather book headed Comments from Visitors had moved from the exit side to the entrance side. He would never have made such a faux pas. What could be more off-putting to a visitor than a request for an opinion before they had seen a single exhibit?

He flipped open the cover. The lone manuscript sentence carried the power of speech:

Liked the totem poles the best.

Visitors: 0

How? He glanced up, down, sideways. Nothing had changed, and the escalators, landings and walkways offered no hiding place. ‘AI can do anything’ had been the watchword at school, but AI cannot pick up a pen and write.

A metallic clink drew his gaze upwards. A panel had opened in the Dome’s ceiling and through the space a young woman was descending on a steel hawser attached by a belt to her waist.

How could anyone get up there? He had seen the Museum from outside only once, but the Dome had towered over him, sheer and unclimbable.

His desire for company evaporated. For years, the prospect of a visitor had been his sustaining hope, but faced with the reality, he just wanted to be left alone with his paintings, artefacts and furniture.

She dropped from the line like a cat and disappeared from view.

Silence. No escalator started.

‘Hello?’ he stammered. Then, louder, as he thought a Curator should sound, ‘Please report to the front desk.’

Still silence.

He added, like a child playing Sardines, ‘I know you’re up there.’

Panic crept in. Only thieves descend from ceilings. Looking for a weapon, he picked up the stylus from the counter as his feline visitor somersaulted round and round the central stairwell, rolling through every floor to Reception.

‘I’ve always wanted to do that,’ she said.

He stood there, stylus in hand like a dagger, mouthing like a goldfish. She was slim, with short dark hair and grey-green eyes. She wore grease-stained jeans and a black T-shirt emblazoned with ‘WANTED ALIVE’ in gold letters. She propped herself against the counter as if she co-owned the place.

‘There is a front door,’ he said.

‘Have you been out there?’ she replied with amused incredulity.

‘I’m the Curator. I stay with my exhibits.’

‘You’d last five minutes, Mr Fogg.’ She paused to reflect. ‘Say three without a chitin suit.’

‘How do you know my name?’

‘Mine is Morag, for better or worse.’

Was she implying that she too lived in the Dome? The possibility of a hidden space for another tenant had never occurred to him. He dismissed these unsettling possibilities and unleashed his opening screed on what he took to be her favourite exhibit.

‘You probably don’t know, but most totem-poles were made from an old-world tree called the Western red cedar. But one of ours, the one with the tree motifs, insect wings and blossom, is reputed to come from the long-lost Amazon rainforest, and its wood—’

‘I’d kill for a coffee.’

‘And its wood is so rare, it’s nameless . . .’

Belatedly, he grasped that her attention was already wandering.

‘I really would,’ she repeated.

He reluctantly dismounted from his runaway horse.

‘The Rearranger has gone rogue. I entered the code for coffee and got a virtual antique trumpet. Twice.’

She walked up to the device, examined the trumpets and tapped the keyboard. The trumpets gave way to two steaming cappuccinos.

‘If a coffee produces a trumpet, then a trumpet should produce a coffee. Simple, really.’ She paused, turned serious. ‘But troubling. You got virtual trumpets; I got virtual playing cards – a double hand, in fact. It’s telling us something. Or AI is.’

‘You have a Rearranger? Where?’

‘In my living room.’ She flicked a finger upwards.

‘But that’s the ceiling.’

‘Your ceiling is my floor.’

‘How long have you been here?’

‘As long as you.’ She lolled against the Reception desk, casual as you like.

He felt invaded. Baffled, he took a sip of coffee and strove for control. He was the Curator, after all. ‘That was you – desecrating the Visitors’ Book?’

‘I’m a night owl,’ she said airily. ‘I drop in when you’re asleep.’

A suspicion took root. ‘Was anything else you?’

‘The stopped clock wasn’t me and the trumpets weren’t me.’

He grinned. He had spotted the absentee. ‘But the pill was.’

‘Maybe. Anyway, it’s not a pill, it’s a momenticon, and momenticons are rare and special. Consider yourself privileged. More importantly, a trumpet is a call to action, my cards suggest we each have a hand to play, and the clock has stopped dead at three years. Someone’s telling us a new chapter is about to begin.’

‘Like who?’

‘Like whoever built this place.’ She downed her coffee. ‘Look, I’m not here to interrupt your working day, but this is quite an anniversary and I’ve been perfecting codes for champagne and cake. I’ll be back at six.’

She returned the way she had come, hauling up the hawser and closing the roof panel behind her.

Fogg pinched himself. His world had fallen in. Now he would have to share. Worse, he would have to entertain.

Then the questions arrived, multiplying like buds on yeast. Where precisely did she live? How had she acquired her own Matter-Rearranger? What was her purpose? And how had she been saved?

Maybe champagne and cake would release the answers.

She didn’t think he would follow, but she still slid both bolts across.

She made her way at a crawl, then a crouch, and then upright to her own living space, where she backflipped on to the magnificent four-poster bed, her only act of burglary. She had fallen in love with the luxurious red eiderdown and matching curtains, not to mention the label: The Bed of the Sun King. Ha-bloody-ha. A Sun King! It had been a brute to deconstruct, transport and reassemble, but well worth the investment. With the curtains drawn, you could be anywhere. You could dream like a child.

But not now, for she had opened the door to cause and effect. She was no longer the sole mistress of her fate.

And what a gamble! Fogg knew the dry contextual facts behind his exhibits, but was there more to him? He had arrived a few days after her in the same gimcrack craft, which had then buckled, sundered and subsided to join the ubiquitous dunes. He had entered the Dome with an old-fashioned suitcase and the lost air of a refugee.

The compelling inference that she and he had been deliberately placed together helped decide her not to make contact.

His obsessive rituals, strict to the minute, reassured her that she had been right, although he had revealed a few plusses. He made up passable stories, always themed on a painting, which he narrated out loud, and he kept his temper. She would have demolished AIPT long ago. From time to time, he would endure a recurring nightmare in the early hours, during which he would lie face-down, flailing his arms. That interested her, but she could not square this wild subconscious behaviour with the obsessively punctilious approach to his daytime activities.

Anyway, now she had no choice. The clock had stopped; AIPT had told Fogg it was time to explore; the Matter-Rearrangers had delivered a hand of virtual cards and virtual trumpets. Somehow they were to be moved on, and together. She felt it in her bones.

She packed her shoulder bag with essentials. She had two jars of momenticons: a large jar containing the fruit of three years’ hard labour, with a single-page guide which matched each pill’s symbol to its particular painting, and a smaller bottle of duplicates of her favourites. She havered before packing both. She might never return.

She lay back, coaxing her brain to rest . . . until . . .

The green panel she had connected to the security screens on the main floor blinked.

Visitors: 2

Visitors! She ran to her window and peered down, forgetting in her excitement that the curve of the Dome concealed the entrance. She switched her view to the airlock monitor. An image, rich with disturbing implications from her past, stared back.

‘Shit,’ she muttered, ‘so soon – and them of all people.’

Two young men, or rather, overgrown boys, were ascending to Reception, hand in hand. They were convex in all respects, fat in body and round in face. Even the laced shoes had a spherical look. Identical twins in identical clothes: bulging cream trousers with three golden buttons spaced equally around the waist, and vertical rows of the same buttons on either side of their orange-brown tunics. Each wore a blue cravat and a white-and-red quartered schoolboy’s cap with a red peak.

They stepped off the escalator and put down the black leather bag they had both been holding by its single handle.

‘This is Tweedledum,’ said the one on the right to Fogg, introducing the other. ‘Dum for shorthand.’

‘Likewise, Dee,’ said the other. ‘Tweedledee for longhand.’

‘But you’re from a book.’ Memories of that book flooded back.

‘We should all shake hands,’ said both.

Fogg did so. Their grip was uncannily strong.

‘Welcome to the Museum Dome,’ Fogg mumbled. This had to be a prank – but their demeanour was unsettling. They spoke in pairs like a well-rehearsed double act.

‘We’re looking for something. But before we go a-hunting, we need a name,’ said Dum.

‘Nobody’s nothing without a name,’ added Dee.

‘We can do names as we go along,’ replied Fogg.

But they just stood there, grinning inanely, each one with a hand on the other’s nearest shoulder, impassive, but expectant.

He faced a familiar humiliation. ‘All right, it’s F-F-F—’ He stopped, relaunched. ‘F-F-F-Fogg.’

‘Now we hear you,’ they responded in unison, ignoring the stutter. It only afflicted him with ‘Fs, which he therefore studiously avoided.

Knives glinted in their trouser waistbands. Delinquent schoolboys.

‘Cutlery on the counter, please,’ Fogg said firmly.

‘That’s not very polite,’ said Dum.

Fogg had no intention of kowtowing. ‘Rules rarely are.’

‘Foggy thinks we’ll carve love hearts on his furniture,’ said Dum.

‘Or on the trees in his pictures,’ added Dee, ‘nohow.’

Abruptly they repositioned themselves, each placing a hand on Fogg’s shoulders.

‘You here on your own-ee-o?’ asked Dum.

Fogg saw no prospect of disarming them, so he played along.

‘You get an answer, I get a question, then you give an answer,’ he replied jauntily. ‘How about that?’

‘Deal,’ said Dee.

‘Consider it signed, sealed and delivered,’ added Dum.

‘You’re my first visitors, as you can see.’ Fogg flicked a finger at the 2 on the panel by way of confirmation.

‘Why’s the clock stopped then?’ said Dee aggressively.

Dum broke away and flicked open the Visitors’ Book.

‘No visitors? So who’s been writing in your book?’

‘I have, pour encourager les autres,’ replied Fogg hastily. ‘But it’s my turn now. Why are you wearing those costumes?’

‘We . . .’

‘We . . .’

‘We’re looking for an item of headgear,’ said Dum, who appeared to be the brighter of the two. ‘And we have to help Alice to the next square as she’s badly lost. She may be wearing a blue dress, white socks and a hairband. Or she may have grey-green eyes, short dark hair and a gamine appearance.’

‘Contrariwise, she may not,’ added Dee, ‘in these troubled times.’

A swirl of questions beleaguered Fogg. Their fidelity to the illustrator’s image was extraordinary. Only the faces differed, and even then, not by much.

‘Where did you get those splendid costumes? How come they’re so authentic?’

‘That’s four questions,’ countered Dum.

‘No, it isn’t, it’s two, and you asked me three.’

‘One question asked of two people is two questions, ’cos you might get different answers,’ declared Dum.

‘Have you seen her, or haven’t you?’ asked Dee, slapping a thumbnail photograph on the counter, a grainy but unmistakable likeness of the young woman who had been roosting in the eaves of his Museum.

Fogg was no expert on people. Indeed, he had been told that he was ‘challenged’ in that department. But he did not like their drift, and he had not forgotten her T-shirt: WANTED ALIVE. So he peered and feigned puzzlement.

‘Don’t think so. No. Nope.’

A mistake.

‘He’s had no visitors, yet he’s puzzled,’ said Dum, ‘nohow.’

‘Got any of these?’ added Dee.

A handout landed beside the photograph. It bore the heading Genrich Infotainment above a picture of a pill in a vivid chequerboard buff-and-white, quite different to the sickle and star on his pill, and beneath it, the caption Looking Glass Wonderland.

This time Fogg had no need to feign bafflement. ‘Nope,’ he repeated.

‘It’s all Greek to him,’ muttered Dee, shaking his head.

‘Spell encyclopaedia then,’ hissed Dum, thrusting a blank piece of paper on to the counter. Fogg obliged.

A second mistake.

‘That’s not the writing in the Visitors’ Book,’ shouted Dum in triumph. ‘It’s time for a Fogg-march.’

The identical twins manhandled Fogg up several escalators. He fought, but they were surprisingly strong, and in no time, he found himself dangling in space, wrists and ankles in manacles, peering helplessly up at the ceiling.

Dum pulled a miscellany of items from the black bag and assembled a silver drill as long as a telescope, which he fixed to a chain.

Dee pulled on a pair of gloves.

‘Where is Alice?’ and ‘Where’s our fix?’ they yelled as the drill closed in on Fogg’s face.

Morag in her eyrie frantically split and joined wires and adjusted timers and programmers. Only one manifestation could terrify these terrorists. You had to play by their book. She had one long shot, or Fogg was foie gras.

Fogg stared ceiling-wards and reflected on the futility of his existence. Having learned all there was to know about the Dome’s exhibits, he had enlightened no one and now faced oblivion at the hands of his first outside visitors.

‘Left a bit, right a bit,’ commanded Dum as the spinning silver point closed on Fogg’s right eyeball.

Still they shrilled, ‘Give us our fix, fix, fix—!’

And,

‘Where’s Alice?’

Fogg felt an atavistic loyalty to his new tenant. ‘You can both f-f-f-f-off.’

‘An “aye” for an eye.’

‘A “no” for a nose.’

Then it happened.

The ceiling lights dimmed, revived and dimmed again in an irregular sequence, fashioning the effect of a huge dark bird circling from one end of the Museum to the other.

‘The crow, the crow!’ the twins shrieked, rolling down the up escalators like beach balls. The abandoned drill fell point-first, burrowing into the floor several storeys below. Fogg, legs akimbo and face to the ceiling, barely grasped the turnaround until his visitors’ screams tailed off into silence down by the Museum entrance. He closed his eyes, trying to recapture the tranquillity of his previous existence.

Rewind, rewind.

‘Wake up,’ cried a familiar voice, ‘or you’ll dislocate your shoulders.’

With the aid of a pulley-cum-brake, Morag raised. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...