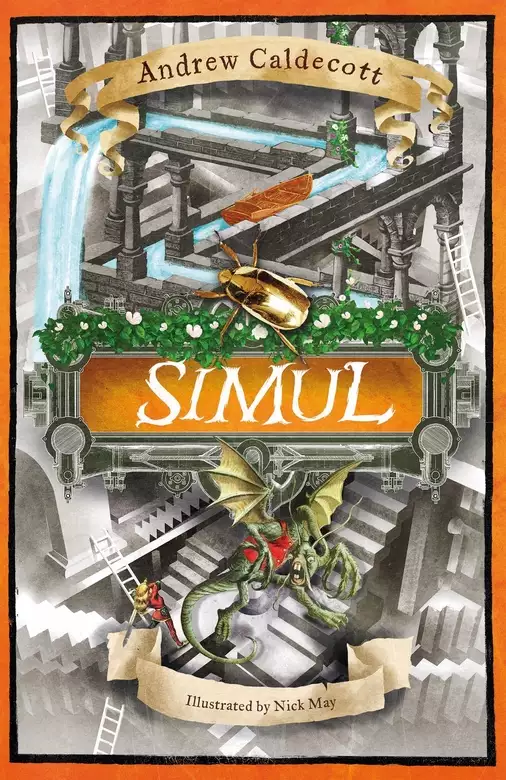

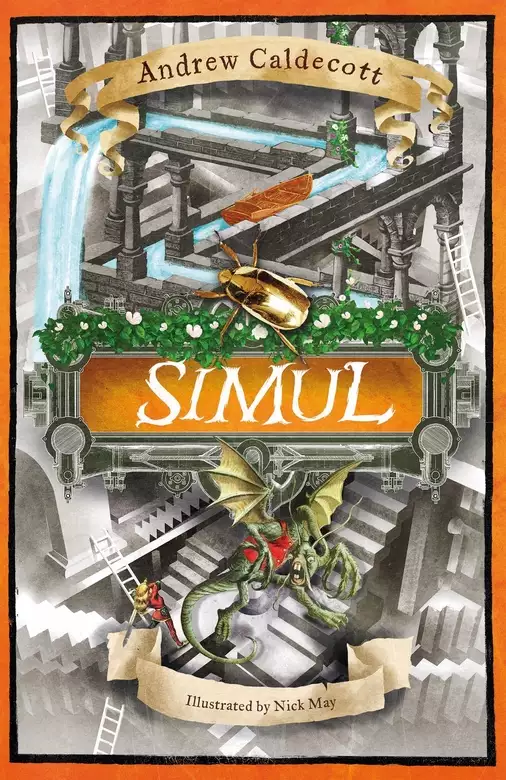

Simul

- eBook

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

From Andrew Caldecott, the bestselling author of ROTHERWEIRD, comes the jaw-dropping conclusion of the MOMENTICON duology - an epic adventure like no other!

'Remember Simul' - the last words of a dying man, and the key to mankind's survival.

Words which take Morag, Fogg and their friends on a wild ride through caverns and over mountains, into old paintings, to a university unlike any other and up the lethal Tower of No Return. A ride where mythical beasts, legendary monster-hunters and a corrupt establishment lie in wait . . . while the weather-watchers look on and bide their time.

It's a race against extinction too . . . for nature herself is bent on vengeance.

'Special and dangerous properties . . . opens a series of trap-doors in the readers' imagination' Hilary Mantel, Booker prize winning author, on Rotherweird

Release date: January 18, 2024

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Simul

Andrew Caldecott

Audiences

Down the passage in Tiriel’s Tower, men and women on plastic chairs and the Tempestas payroll map the progress of the corrosive storms sweeping away the last remnants of the old world, but here in Lord Vane’s study, news arrives, and orders leave, on paper. He is deeply radical and yet deeply conservative. One such order has brought his only son’s young governess, Nancy Baldwin, to the door. She knocks.

‘In!’ bellows Lord Vane, who does not wait for the door to close before delivering his diatribe: ‘Why is that boy simpering over art books?’

‘I was asked to give him an education,’ replies Miss Baldwin gamely. Stocky in build, with a plain but resolute face, she stands her ground physically as she does in argument.

‘He is heir to the world’s last kingdom, not a student of daubs and scribblings.’

The boy, thirteen today, stands awkwardly to one side of his father’s large, ornate desk, hands behind his back. ‘It’s only two hours a week,’ he interjects quietly.

‘You speak when you’re spoken to,’ snaps Lord Vane in a voice which cows most opposition.

But the boy has learnt courage from Miss Baldwin.

‘She teaches me Machiavelli too,’ he says.

‘Does she, now? It is better to be feared than loved, if you cannot be both. Do you teach that, Miss Baldwin?’

The boy interrupts a second time.

‘Two impulses drive us: love or fear. Isn’t that the choice we rulers have to make?’

Lord Vane rises from his equally ornate chair. He approaches his son, as if to strike him. Instead, he spins round to face Miss Baldwin once more.

‘From now on, he’ll be taught by the Master of the Weather-Watchers.’

The boy’s head sinks low to his chest.

‘Mr Jaggard is no teacher,’ says Miss Baldwin.

‘Why do you say that?’

‘He is not a man who shares.’

‘He will if I tell him to.’

‘And he revels in our tragedy.’

‘Our tragedy? You mean theirs! If the world had listened, if the world had acted, most could – would – have survived. More to the point, Jaggard has a clever son about the same age. They’ll get on famously.’

Clever, indeed, she thinks, but slippery as an eel and not her idea of a good influence.

Lord Vane softens, and that is his reputation: generous, once he has had his way. ‘I’m not dismissing you, of course. You can help young Potts with the library databases.’ He turns back to his son. ‘But no art books for you, now or ever.’

Next in is a fresh-faced Peregrine Mander.

‘Ah, young Mander! Is the art of the old world logged and recorded?’ asks Lord Vane, sitting down again at his magnificent pedestal desk.

‘Hardly all of it, my Lord, but what I hope is the crème de la crème.’

‘Your postcard idea was genius. No galleries to turn people soft, but a space-efficient record of our wasted craftsmanship.’

‘I’m pleased you approve, my Lord.’

‘Just keep my son away from them. Arty-farties are unfit to govern.’

‘I have limited experience on that topic,’ replies Mander cautiously.

‘Miss Baldwin says you’ve mastered the Matter-Rearranger.’

‘You never master the culinary arts, you merely develop them.’

Lord Vane smiles rarely these days, but he does now.

‘I have to say, Mander, you speak like a man in his sixties.’

‘I’ll take that as a compliment, my Lord.’

‘Good, because I’ve a proposal. I need a fetcher and carrier. Someone to make mealtimes a pleasure. Someone trustworthy, to keep an eye. Are you up for it?’

Mander nods gently as Lord Vane encourages him.

‘I want you to stand out and be respected. So, how about the traditional kit?’

‘Which tradition is that, my Lord?’

‘Personal service.’

‘Ah, the gentleman’s gentleman.’ Mander mulls, but briefly. ‘I shall visit the Tempestas’ tailor this very afternoon.’

In Mander’s complex mind, it is rare for an offer to seem instantly right, but this one does. He will be inside the citadel of power, yet will pose no threat in his white tie and tails. The dress and deferential language of the butler will make him near invisible, but, boy, he will listen. And, in his own way, he will act. Lord Vane has no idea what a promotion this is.

‘So, you’re game?’

Game he is, and game is the word.

‘I trust I’ll not disappoint, my Lord.’

‘That’s settled, then. I feel this will be a long and fruitful relationship. Keep an eye on my son, too. We can’t have a wimp for an heir.’

Two satisfactory audiences, from Lord Vane’s perspective: objectives accomplished without conflict. But the next may be more testing.

A young outlier waltzes in, no respectful pause at the threshold like the others. She looks a maverick too: one eyebrow higher than the other, a nose which tilts slightly to the right, a quizzical lopsided smile. At least the eyes are the same colour. They say she is a sponge for detail and mistress of the colourful phrase.

‘I trust you are pleased with your appointment, Miss Crike?’

‘Tickled pink.’

Tickled pink is not how his patronage is usually greeted. I’m very grateful, your Lordship would be a start.

He gives her a prompt: ‘The Official History of Tempestas. That’s quite a subject and quite a privilege. The library has a whole shelf set aside.’

Crike eyes the old fox. She could write the official version right now. Tempestas warned like an Old Testament prophet. Humanity closed its ears and paid in fire and brimstone. Think Sodom and Gomorrah.

‘What is an official history?’ she asks.

‘A narrative provided by those who know. Mr Venbar and Mr Jaggard will give you whatever time you need. As will I, of course.’

‘An excellent start,’ replies Miss Crike, lingering over the last syllable.

‘The best historian in your year, I’m told.’

‘My university had spires, meadows, quads laid to grass and a river. All dust now. Nothing like loss to strengthen your sense of history.’

Lord Vane softens, though less sure, this time, that he has got his way. ‘I went to a university like yours. I know how you feel. I’ve even remembered my college in my will.’

Hilda Crike bobs, more an acknowledgement than a curtsey, and withdraws.

So, Crike the spy and Crike the actress are born, for history is about what truly happened: a task for stealth and subterfuge. She might even get a chance to remedy whatever faults the truth reveals. She is ambitious to shape history as well as record it.

On reaching the library, an oddity strikes her. How can Lord Vane donate to a college which no longer exists?

3

Last Words

Hilda Crike pores over the weather-watchers’ charts and their reports to Lord Vane. She has burnt the midnight oil mastering the vagaries of the weather, both cause and effect. The more she learns, the more she suspects Tiriel’s Tower of presenting design as accident, but there are gaps which only Lord Vane can fill, and he has been critically ill for weeks now.

Peregrine Mander taps her shoulder. She is the only one he addresses with any trace of familiarity. He has, like a chameleon, turned into a fictional gentleman’s gentleman. Potts is Mr Potts; Baldwin is Miss Baldwin.

‘Miss Hilly, you are wanted. The celestial plane awaits his Lordship.’

She follows him up the great staircase to the private quarters with head bowed. For all his sternness, she has grown fond of Lord Vane.

He lies in a four-poster bed, head propped on a jigsaw of pillows. His arms lie over the sheet, his skin peeling like rice paper beneath a nightshirt as white as a shroud.

Mander busies himself with his master’s brow. Beside the bed, a young woman kneads a mix of plaster of Paris, wax and dough-like gel. Lord Vane’s son sits, motionless in a corner, head in hands.

The dying man retains his humour.

‘She’s to strike while the iron is hot,’ he says with a nod in the young woman’s direction. His chest grumbles like pebbles shaken in a jar. The voice wavers, but he still hits the consonants hard and is easily understood.

‘Save your breath, my Lord,’ whispers Mander.

Lord Vane ignores the advice. Why else bring her here?

‘Is your History done, Miss Crike?’

‘Yes, my Lord.’

‘But you have questions, surely. Now’s the time. It is not my brain which fails.’

Lord Vane gives Mander a glance. Their communication is close to telepathic. He gestures for the woman preparing the death mask to leave. To Crike’s surprise, Lord Vane’s son follows her out.

‘Ask away,’ he says.

Speaking, Crike knows, aggravates the pain. He wants candour, not flattery.

‘I believe the weather-watchers misled you,’ Crike says. ‘I’ve made quite a study of meteorology. They may not have created the murk, but they exploited it for their own purposes. Mr Venbar would neither confirm nor deny.’

Lord Vane’s eyelids open and close like shutters, the way an owl blinks.

‘Watch the Jaggards for me,’ he mumbles. ‘Father and son.’

His right hand rises centimetres above the sheet and sinks. Ask again, the gesture says.

‘You once told me you remembered your college in your will. But there is no record of any such place.’

Lord Vane’s reaction surprises even Mander. He rises from his pillows like Lazarus.

‘Arbor spirantia,’ he says. ‘My mortal sin . . . to give . . . to give to him . . . Absolve, please absolve me.’

Crike, on instinct, kisses him on the forehead.

‘Resurrection . . . resurrection . . . remember Simul,’ stammers Lord Vane, before sinking back, seemingly at peace for his confession. The stertorous breathing gently fails. Mander closes his eyes and readmits the son and heir.

‘It’s time,’ he says to him, ‘my Lord.’

4

A Wake

The coffin, on its wheeled bier, runs down a gentle slope through the chitin shield and into the murk. There is no grand mausoleum. Only the first Lord Vane’s forbidding death mask, floating in a niche in the study, reminds his heir of the burdens of rule.

Rows of Tempestas’ workers stand in silence. There are outliers and a sprinkling of northerners too.

Mander has substituted a black tie for the white, but otherwise there is no change in his attire. Beside him, the second Lord Vane’s stern expression hides his thoughts. Grief mixes with a sense of liberation and opportunity. His father delivered deep winter. He must usher mankind into spring.

Jaggard, father and son, stand in front of them. The son is already an assistant weather-watcher.

There is no sentimental music, not even a drumbeat. Mander crosses himself before walking over to his new master.

‘My Lord, it’s traditional to hold a wake for the departed. To toast the past and talk of the future. I have cleared your Lordship’s study and invited those you may find useful.’

‘Like those dreadful Jaggards?’

‘One must engage with the powerful, so they’ll be there. But I’ve also dabbled in future potential, if you get my meaning.’

Lord Vane does. How else to rule? You choose your lieutenants, and not only the old guard with all their baggage.

‘People I can trust?’

‘Or people who need watching.’ The transition is seamless. The butler’s manner has not changed one iota between serving father and son. Mander extends an old-fashioned arm, as if he were making way for a woman. ‘You lead, I follow,’ he says.

The new Lord Vane wonders quite how true that is, or indeed ever was.

Photographs from the late Lord Vane’s life adorn the study’s walls: the baby who looks like any other; the youthful adventurer-cum-naturalist; the activist years; the founding of Tempestas and the weather-watchers; in full flow, rebuking the world and its leaders; the building of Tiriel’s Tower; prophecies come true in scenes of levelled cities and apocalypse; and, dotted among them, intimate and incongruous family snapshots.

Fifty-odd guests browse the walls and raise their glasses when the new Lord Vane enters. He goes first to a young man, about his age. Squat and bull-headed, he stands alone, dressed in ash grey.

‘Lord Sine – our lives march in step. I was sorry to hear about your father.’

‘What is there to be sorry about? Death is a natural process. We resume with the talents our forbears bequeathed.’

‘Indeed. How goes Genrich?’

‘A better model of man is on the way.’

‘Better in what way?’

‘A streamlined brain: no art, no self-indulgence, no small talk.’

‘And no challenge to your orders?’ replies Lord Vane good-humouredly.

‘They’ll work for each other’s survival,’ replies the master geneticist.

‘Will you still take in outliers?’

‘Only exceptional ones, if any are left.’

Lord Vane beckons Oblivious Potts over. ‘Mr Potts, you once told me we humans are genetically ninety-nine per cent identical. Meet a young man who plays with the one per cent. Mr Potts, Lord Sine; Lord Sine, Mr Potts.’

‘That one per cent can do an awful lot of damage,’ says Potts.

Having started with duty, Lord Vane moves on to pleasure. Miss Baldwin, his childhood tutor, is gossiping with Miss Crike in the far corner.

‘We’re bemoaning the fact that your father, though photographed to death, was never painted,’ says Crike.

‘He disliked artists,’ says Miss Baldwin, ‘and art. There isn’t a paintbrush in the building. Or an art book.’

‘A point I make in my History.’ Miss Crike nods. ‘Your father and the late Lord Sine had more in common than meets the eye.’

At that moment, a desire to beat his own path seizes Lord Vane. Whatever the cause, there is a lightning strike. Half-memories of painted buildings dance in his head. His father’s legacy – the Tempestas Dome and its replicas of lost fauna – give way to a grander vision.

‘We must uncover the sky,’ he says.

‘How, exactly?’ asks Crike, intrigued.

‘Technology got us into this mess. Technology can get us out of it.’

He suffers a second lightning strike in as many minutes. A young woman stands at the door in conversation with young Jaggard and is not relishing the experience. Lord Vane has never seen her before. Mander appears, as if by magic.

‘Allow me to fill your glasses, ladies, before I whisk his Lordship away to meet the unusual Miss Miranda.’

The two women share a wink. Unusual. Mander knows how to bait a line. Lord Vane leaves them with an instruction.

‘Remember today, Miss Crike, for the next volume of your History. At my father’s wake, I said we would uncover the sky.’

Mander shimmies across the floor with his new master in tow. ‘This is Miss Miranda,’ he says, ‘from the Tempestas Dome. You share an interest in colour and texture. And nobody works harder than Miss Miranda.’

Mander slides away.

She wears black trousers, a black shirt and a black-and-green checked jacket. Her face is a near-perfect oval, as in one of those paintings which his father denied him all those years ago.

‘Black for death and green for resurrection,’ she explains.

He is wary of beauty for beauty’s sake, but her smile mesmerises. It contrives to be both respectful and mischievous.

‘What’s your interest in colour and texture?’ he stammers. ‘For me, it’s paintings.’

‘For me, jewels and jewellery.’ She pauses. ‘Don’t ask. I’ll bore you.’

Only then does he see that her earrings match the streak of purple in her eyes. Amethyst, he thinks. ‘I’ll be the judge of that.’

‘Everyone has their stone. Take your Lo—’ She stops. ‘Apologies, my Lord, I was about to be presumptuous.’

Not presumptuous, he thinks, calculated. But he cannot resist. He is netted.

‘Go on.’

‘Diamonds are for showmen, so they won’t do. Nor rubies – you’re not the fiery type.’

He feels an edge of disappointment, but the game goes on.

‘Nor are you cold enough for sapphires or devious enough for emeralds. I’d go for a semi-precious stone. They’re every bit as deep, but less swanky.’ She is playing with him. ‘Onyx,’ she says. ‘The best form: dark chocolate with an eye of white. It’s a layered stone, and the core is mysterious.’

Decades later, when mechanical horsemen are spearing him to death on a pond in Winterdorf, these two lightning strikes at his father’s wake are the memories he clings to as the ice closes: a vision of a painted town made real, and an indefinable woman. Both have shaped his rule for good and ill.

6

The New Boy

Gilbert Spire is thirty-three, but he does not feel it. He languishes in anti-sceptic surroundings; he has a number rather than a name; and the work – gene splicing – is as distasteful as the name of his new employer, Genrich. Gone are the home comforts, wife, daughter and library, and, in their place, solitary quarters as pinched as a monastic cell.

Yet DNA is the heart of life, and he has a curious disposition. He is proficient in finding favour, and the cerebral toad in charge, the second Lord Sine, appears to enjoy his company.

‘Might I see Genrich’s early research?’ he asks Lord Sine, after months of hard labour.

‘Why would you want to do that?’

‘Early research isn’t always wasted research,’ he replies. ‘And, as your father spared my family, I thought a show of reciprocal interest was called for.’

Lord Sine finds Spire’s quaint nostalgia amusing.

‘In your leisure hours, if you must.’

Leisure hours! At Genrich! In the company of near-identical workaholics with no humour and no outside interests! God pray they never bring his daughter here.

The archives inhabit dingy corridors deep underground. He ferrets away through databank after databank. Endless lists of unproductive mixing and matching yield nothing. Nature is Spire’s subject of choice, not man. On a whim, he uses the search facility. In a sea of technical terms and human genomes, he finds a rogue entry: the word arbor, Latin for ‘tree’, with a cross reference which leads him to a stack of boxes which house discarded genetic matter.

All are numbered and lettered, save one – a rectangular strongbox, which, unlike the others, is secured by a complex dial-lock. The Highly Classified marking is a red rag to Spire.

He tries various combinations until the simplest works. After entering arbor and the reference number, the lid flies open.

The data disc inside records numerous attempts to merge a base cellulose material with other cellulose matter.

Inside the box are two smaller containers. One has various tiny trays, now empty, marked with the Latin names of well-known trees. The other is also empty, save for a printed label marked Arbor. Both containers are twisted and peppered with holes. At the bottom of the box lies a single piece of paper.

This box holds the surviving material from roots and cuttings given to me by the first Lord Vane on my fortieth birthday with a challenge: create a seed or reproduce a plant which fruits. One genome is unknown. Lord Vane claimed it came from a tree, now extinct, famed for its healing qualities. It was a trap. Do not attempt the task under any circumstances. Still less attempt disposal.

Department XI; Chairman’s personal classified Order 113.

Spire is intrigued. If the material were truly dangerous, disposal would be the obvious solution; and the empty trays suggest disposal. Yet that course has been expressly prohibited. A second conundrum connects to the first. An organisation as fastidious as Genrich would never seal dangerous material in damaged boxes, nor would they preserve, still less seal, empty trays.

Spire removes the two inner boxes to find in the corner of the container a tiny black object, little bigger than an apple pip. If it is a seed, the accompanying note makes little sense. Why give instructions not to attempt a task which has already been completed?

Unless . . . a bizarre interaction within the box has created the seed – a solution which would explain both the empty trays and the damage.

He seals the tiny seed in a bottle and secures the bottle in the original strongbox.

Over the ensuing weeks, he studies the seed’s unique chemical and molecular structure. But his late-night research does not pass unnoticed. He is summoned by Lord Sine.

‘My other workers do their hours diligently and then retire to chess or sleep. You work and then scrabble about in the past. What’s so enthralling about my father’s old papers?’

‘I suspect you know already.’

‘I’ve examined the data disc which so intrigues you. What use can a futile attempt at creating a plant of some kind be to anyone?’

‘Your Lordship’s knowledge of genetics surpasses mine. I can only say the structures are most unusual.’

‘What if they are? Plants can’t reason. We have Matter-Rearrangers for food. There’s no sunlight from which to seek shade. The murk has poisoned the earth and the air. You’re wasting time and reducing your energy for real work. And that level-one strongbox is hardly apposite for such mundane material.’

‘Your father worked on it.’

‘Each generation should be wiser than its predecessor. The fact my father wasted his time is no reason for you to follow suit.’

‘It’s my equivalent of chess.’

Uncharacteristically, Lord Sine concedes. In truth, he too is mildly interested in the organism’s structural novelty.

‘If you must, but once a week only, and not beyond midnight. I want you fresh. I’ll be watching. And be sure to report anything unusual.’

7

A Fateful Encounter

After a Praesidium meeting, the Vanes return to their quarters in the Genrich Dome. It is a night of storms so intense that they can hear the rain thrashing on the Dome’s chitin shield.

The second Lord Vane and his wife are playing cards. She has made the sitting room stylish but cosy. In shared tastes, the marriage has been a success; less so in other ways.

‘We look like a pair of dotards, whiling away our final days.’

No children, she means, and by implication not enough passion. She has a hundred ways of saying it.

‘We’re doing our best.’

‘You could talk to Lord Sine.’

‘As could you.’

The outside door is struck – unprecedented at this hour, with the curfew in force.

‘I’ll go,’ says Lady Vane, drawn by the vigour of the knock. Give me adventure.

And the doorway does. A man, their age, stands tall. He exudes energy.

‘I’m so terribly sorry, but it’s the weather. I couldn’t sit in my white box a second longer. I had to hear the storm and, having heard it, I craved company – real company.’

Only then does the visitor pause, taking in the beauty of Miranda Vane and her surroundings, more like his old home than the Genrich Dome.

‘Might I ask who you are?’ says Lord Vane, as intrigued as his wife. ‘You’re not the average Genrich worker.’

‘Did I not say?’

‘You didn’t,’ says Lady Vane. ‘Even though your opening speech was all about you.’

‘Gilbert Spire. A lucky outlier spared by Genrich.’

‘What are you doing here?’ asks Lord Vane.

‘I work for Lord Sine. But, look, you’re missing a mother and a father of a tempest, up there. Live theatre, with special effects! We can access the service hatch without anybody noticing. They’re all tucked up in their identical beds.’

He looks and sounds like a schoolboy proposing truancy.

‘We can hear it down here,’ says Lady Vane.

‘That’s just a muffled echo. You can’t feel it.’ He taps his chest and turns to Lord Vane. ‘Come on, you’re the weatherman.’

Lord Vane smiles as he throws down his cards. ‘I had a losing hand, anyway.’

Spire takes them into a gloomy passage on the floor below, produces a screwdriver, unscrews a near-invisible panel in a column and disappears up a ladder, past a forest of wires. Lord and Lady Vane look at each other. A new force has entered their lives. Lady Vane makes a mental note. He is the first man not to call her husband ‘his Lordship’. She senses a rare gift of instant friendship, if not more. They follow him up – and up.

The visitor is right. The muffled version below is an anaemic shadow. The Dome sheers from bright orange to pitch black as the lightning comes and goes, while shuddering with every deafening blast of thunder. The rain is not constant. It thrashes and swirls across the Dome’s protective skin. Rivulets of water, caught in the glare, give the impression that the chitin is melting. Spire opens his arms as if drinking in this elemental violence.

‘Explorer’s weather!’ he shouts above the din. ‘Imagine being in a balloon!’

‘I’d rather not,’ cries Lady Vane, but his brio is infectious. She gives herself to the storm.

‘Perfect timing,’ adds Spire. ‘It’s right above us!’

Eventually, senses sated, they retreat to the Vanes’ rooms.

‘That was quite something,’ says Lord Vane.

‘And we aren’t even damp!’ enthuses Spire.

‘Perhaps you cooked it up for your entrance?’ says Lady Vane.

‘Darling, really,’ chunters her husband.

Mander enters, as ever omniscient. He carries three glasses and a jug of green liquid on a silver tray.

‘This is young Mander – well, he’s young in spirit. He looked after my father and now he looks after me.’

‘I gather you’ve been sampling the atmospherics, Mr Spire,’ says Mander, with a click of the heels.

‘Mander sees and hears more than ordinary mortals,’ explains Lord Vane.

Mander waves away the compliment. ‘It’s no more brilliant than the hollow in the conjuror’s hat. We have a security camera, and I’ve a way of accessing Genrich’s databanks, including recent arrivals. Unsurprisingly, you match your photograph, Mr Spire. Child’s play. I call this drink Meadowsweet, after the breath mown stalks exhale – or did.’

The pleasantries subside as Spire reveals his deeper self. He talks of glaciers, volcanic activity and polar conditions, and his conviction that they might keep the murk at bay. He talks of tantalum, too – the world’s disappearing essential.

‘I plan to explore the unknown, out there.’

‘In what?’ asks Lady Vane. ‘Journeys are rationed, these days.’

‘There’s no need to ration the forces of Nature. I’ve been studying old-world Airluggers, and there are two moored at the Tempestas Dome.’

‘Now we know why he’s here – to cadge a lift,’ says Lady Vane.

Lord Vane does not register that his wife is playing the game she played with him when first they met, that special brand of teasing which is born of attraction.

‘Nothing so ambitious. I’d just like to give one of them an overhaul. You know, like a boy with his boat.’

Lady Vane slips in her first question with real purpose: ‘Don’t you have a family? Wouldn’t seeing them be a better idea?’

‘It’s not permitted, hence my thirst for diversion.’

He notices the t. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...