- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

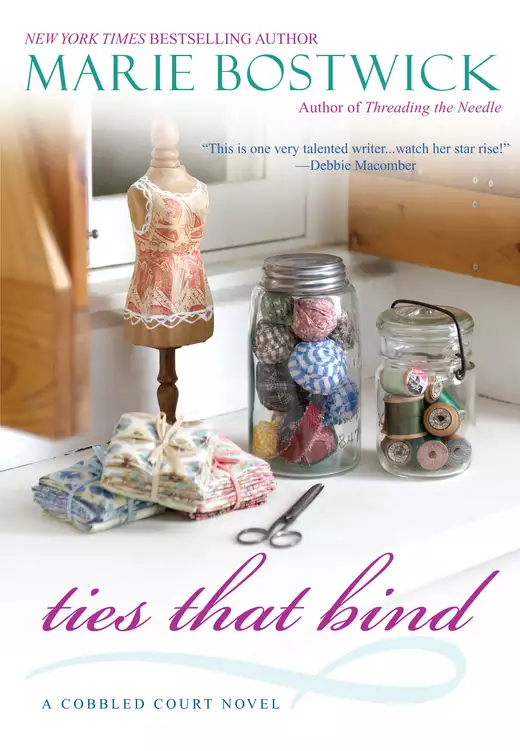

In her compelling, beautifully crafted novel, New York Times bestselling author Marie Bostwick celebrates friendships old and new—and the unlikely threads that sometimes lead us exactly where we need to go.

Christmas is fast approaching, and New Bern, Connecticut, is about to receive the gift of a new pastor, hired sight unseen to fill in while Reverend Tucker is on sabbatical. Meanwhile, Margot Matthews’ friend, Abigail, is trying to matchmake, even though Margot has all but given up on romance. She loves her job at the Cobbled Court Quilt Shop and the life and friendships she’s made in New Bern, but she never thought she’d still be single on her fortieth birthday.

It’s a shock to the entire town when Philip A. Clarkson turns out to be Philippa. Truth be told, not everyone is happy about having a female pastor. Yet despite a rocky start, Philippa begins to settle in—finding ways to ease the townspeople’s burdens, joining the quilting circle, and forging a fast friendship with Margot. When tragedy threatens to tear Margot’s family apart, that bond—and the help of her quilting sisterhood—will prove a saving grace. And as she untangles her feelings for another new arrival in town, Margot begins to realize that it is the surprising detours woven into life’s fabric that provide its richest hues and deepest meaning.

Release date: May 1, 2012

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 368

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Ties That Bind

Marie Bostwick

“People are like stained-glass windows. They sparkle and shine when the sun is out, but when the darkness sets in, their true beauty is revealed only if there is a light from within.”

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross said that, and I’ve been thinking about it a lot lately. Maybe that surprises you. Most of the people I know, apart from my close friends, would be surprised to know I can quote from Kübler-Ross, and for one simple reason: I am nice.

I am. That’s how people describe me, as a nice person, a nice girl. That wasn’t so bad when I was a girl, but when you move beyond girlhood into womanhood, people tend to confuse niceness with lack of intellectual depth. And if that nice person is also a person of faith, they think you’re as shallow as a shower, incapable of introspection or academic curiosity. But mine is an examined faith, composed of inquisitiveness, discovery, and introspection. However, it didn’t begin with me.

I have known and loved God for as long as I can remember. It was as natural to me as breathing. As I’ve grown older and met so many people who struggle with the meaning and means of finding God, I have sometimes wondered about the validity of my faith. Could something so precious truly come as a gift?

I can’t answer for anyone else and don’t presume to, but, for myself, over and over again, the answer has been yes. I don’t understand why the searching and finding should be so simple for some and so arduous for others. I only know that I have been blessed beyond measure or reason. But while peace with God came easily to me, peace with myself has been elusive.

From adolescence onward and with increasing anxiety as the minutes and years of my biological clock ticked on, I waited for the missing piece of myself to arrive, the better half who would make me whole: a husband. And with him, children, a family. That’s what I’d always wanted, and that, I was sure, was what would make me happy. But after reading and meditating on Kübler-Ross, Brother Lawrence, the apostle Paul (“I have learned the secret of being content in any and every situation”), I finally realized that I was not happy with myself because I had never learned to be happy by myself.

And so, more than a year ago, I broke it off with my boyfriend, Arnie Kinsella. It was hard, but it was for the best. I like Arnie, but I wasn’t in love with him any more than he was in love with me. Even so, if he’d asked me to marry him, I’d have said yes in a heartbeat. I know how terrible that sounds, but it’s the truth.

My friends—Evelyn, Abigail, Ivy, Virginia, everybody from my Friday night quilt circle—applauded my decision. They said I deserved the real thing—head-over-heels, candy-and-flowers, heart-throbbing, heart-stopping L-O-V-E.

A nice thought, but it’s never going to happen, not to me. And if finally acknowledging that didn’t quite make my windows blaze with light, at least it saved me from further humiliation and the weight of impossible dreams. I was over all that and I was over Arnie Kinsella.

Or so I thought. Until today.

December

Today, I turned forty.

I wanted to let this birthday pass unnoticed, but when my lunch break came I decided I deserved a treat and walked around the corner to the Blue Bean Coffee Shop and Bakery, known to locals in New Bern, Connecticut, as the Bean.

My table was near a window frosted with little icy snowflake patterns where I could watch people bundled in scarves, hats, and thick wool coats scurrying from shop to shop in search of the perfect Christmas gift. When the waitress came by I ordered a plate of nachos, loaded with extra everything including so much sour cream they ought to serve it with a side of Lipitor.

Six bites in, a glob of guacamole and chili slipped off my chip and onto my chest. Dipping a napkin in water to clean up the mess only made it worse. My white sweater looked like a toddler’s finger-painting project. I was on my way to the restroom to clean up when I spotted Arnie sitting in the back booth with Kiera Granger. That’s where people sit when they don’t want other people to know what they’re up to. It doesn’t do any good. Everybody in New Bern is well informed about the business of everybody else in New Bern.

On another day maybe I’d have been able to forget the sight of Arnie and Kiera sitting in the dimly lit booth, heads together, hands nearly but not quite touching as they talked intently, so intently that Arnie didn’t even see me, but not today. I left my food and twenty dollars on the table and ran out the door and into the street, wishing the blustery December snowfall would turn into a blizzard and hide me from the world.

With only five shopping days until Christmas, Evelyn would need all hands on deck, but I couldn’t face going back to work. I fumbled around in my bag until I found my cell phone. Evelyn answered on the fifth ring.

“Cobbled Court Quilts. May I help you?”

I heard a car round the corner; the engine was so loud that I’m sure everyone within three blocks could hear it. I stopped in my tracks, hoping the heap would pass so I could continue my conversation. Instead, it slowed to a crawl and the noise from the engine grew even louder. I pressed the phone closer to my left ear, covered the right with my free hand, and shouted into the receiver.

“Evelyn? It’s Margot.”

“Margot? What’s all that noise? I can barely hear you. Where are you?”

“I’m going home.”

“What?”

I held the phone directly in front of my mouth, practically screaming into it. “I’m going home. I’m not feeling very well. I’m sorry, but … aack!”

A blast from the car horn nearly made me jump out of my skin. It was more of a bleep than a blast, the kind of short, sharp tap on the horn that drivers use to alert other drivers that the signal has gone green, but what did that matter? At close range the effect was the same. I yelped and dropped the phone, dropping my call in the process.

When I regained my balance, my phone, and some of my composure, I turned toward the street and saw a low-slung, bright blue “muscle car,” rusty in spots and with multiple dents, a tailpipe choking clouds of smoke, topped by a roof rack carrier piled high with possessions and covered with a plastic tarp that was held in place by black bungee cords—sort of. The tarp was loose on one side, exposing some boxes, a big black musical instrument case, and a hockey stick. Quite a collection.

The driver was a man about my age with black hair receding at the temples and brown eyes that peered out from rimless glasses. A boy of twelve or thirteen sat slumped in the passenger seat, looking embarrassed and irritated. The driver said something and the boy cranked down the window. The driver shouted to me, but I couldn’t make out his words over the roar of the engine.

What kind of person shouts at strangers from their car? Or honks? In New England, honking in a situation that is short of life threatening is up there with painting your house orange or coming to a dinner party empty-handed. You just don’t do it.

Climbing over a snowbank and into the street, I noticed that the car had Illinois plates and a Cubs bumper sticker. Were they visiting relatives for Christmas? If they were, I probably knew the family. So no matter how rude he was, I had to be nice.

Shaking my head, I mimed a key in my hand and twisted my wrist, signaling him to shut off the ignition. Instead, he shifted into neutral. That reduced the engine noise to a loud hum rather than an earsplitting roar. Better, but not much.

“Sorry!” he yelled. “If I turn it off, I’m not sure I’ll be able to start it again. Can you tell me where Oak Leaf Lane is? We’re lost.” The boy, who I supposed must be his son, slumped down even farther in his seat, clearly humiliated by his dad’s admission. I smiled to myself. Teenagers are so painfully self-conscious.

“Turn around, take a right at the corner. Oak Leaf Lane is the third right after the traffic light. Beecher Cottage Inn is down about a quarter mile on the left, if that’s what you’re looking for. Or are you staying with family over Christmas?”

Still grinning, he shook his head. “Neither. We’re moving here.” The man leaned across his son’s lap and extended his hand out the window so I could shake it. “I’m Paul Collier. This is my son, James. James is starting as a seventh grader at the middle school after the holidays and I’ll be starting a new job at the same time.”

“Dad!” James hissed. “You don’t have to tell her our life story.”

Paul Collier rolled his eyes. “I wasn’t. I was just making introductions. This is the country, James. People in the country are friendly. Isn’t that right, miss?”

He looked to me for support, but I decided to stay out of it. Paul Collier seemed nice, but I had to wonder how he was going to fit into New Bern. The residents of New Bern are friendly but, like most New Englanders, they are also proud and a bit reticent. They like for strangers to act … well, a little strange, at least initially. And they don’t like it when strangers refer to their town as “the country.” Makes us sound so quaint.

I bent down to shake his hand and changed the subject. “Well, it’s nice to have you here. On Christmas Eve, we have a carol sing with hot chocolate and cookies on the Green. That’s the park in the center of downtown,” I added, realizing they might not be familiar with the term. “And if you’re looking for a place to attend Christmas services, New Bern Community Church is right on the Green too.”

“Great! I was just telling James that we needed to find a church first thing.”

His enthusiasm piqued my interest. Most men don’t put finding a church high on their list of priorities when they move to a new town. My gaze shifted automatically, searching out his left hand, but I couldn’t tell if he was wearing a ring.

What was I doing? When was I going to get over the habit of looking at every man I met as a potential mate? Even if this man was single, his hair was too dark and his forehead too high. Not my type. And he was probably too short. And anyway, I was through with all that. And even if I hadn’t been—which I was, I absolutely and forever was—Paul Collier’s response to my next question would have settled the matter.

“So, you’ve moved here for a new job?”

“I’m a lawyer. I’m starting at Baxter, Ferris, and Long after Christmas.”

A lawyer. Of course, he was. It was a sign, a clear sign that I was supposed to learn to be content as a single woman and stay away from men. Especially lawyers.

I let go of his hand and took a step back from the blue heap; he couldn’t be a very successful lawyer if he was driving such a pile of junk. “Well … good luck. Have a good Christmas.”

“Thanks. Same to you, miss. Or is it missus?”

He was awfully direct, another quality that doesn’t go over well in New England.

“Margot,” I replied, leaving his question unanswered. “Margot Matthews.”

“Nice to meet you, Margot. Merry Christmas.”

He put the car back into gear, revved the engine, made a three-point turn in a nearby driveway, and drove off, leaving my ears ringing. Or so I thought, until I realized that the buzzing was coming from my phone.

“Sorry, Evelyn. I accidentally dropped the phone.”

“What happened? It sounded like an airplane was about to land on top of you.”

“Just a car driving by. Listen, I don’t think I can finish the rest of my shift ….”

“Something you ate at lunch?”

“Sort of,” I replied. “Will you be all right without me?”

“Sure. I mean … if you’re sick, you’re sick. Do you think you’ll feel better if you just lie down for an hour? Maybe you could come in later.”

Evelyn is not just my boss; she’s also my friend. She doesn’t have a deceitful bone in her body, but something about the tone of her voice made me suspicious.

“Evelyn, you’re not planning a surprise party at the quilt shop, are you?”

I told her, I told all my friends, that I don’t want to celebrate this birthday. Why should I? There is nothing about being forty and still single that’s worth celebrating.

“No. We’re not planning a party at the shop. Take the afternoon. But you’ve got that meeting at church tonight, don’t forget. Abigail called to see if you’d pick her up.”

The meeting. I was so upset that it had completely slipped my mind.

I sighed. “Tell her I’ll pick her up around six fifteen.”

In the background, I could hear the jingle of the door bells as more customers entered the shop. I felt a twinge of guilt. I almost told her that I’d changed my mind and was coming in after all, but before I could, Evelyn said, “I’ve got to run. But feel better, okay? I know you’re not happy about this birthday, but whether you know it or not, you’ve got a lot to celebrate. So, happy birthday, Margot. And many more to come.”

“Thanks, Evelyn.”

I built a fire in the fireplace and stood watching the flames dance before settling myself on the sofa to work on my sister’s Christmas quilt. Quilting, I have found, is great when you want to think something through—or not think at all. Today, I was looking to do the latter. For a while, it worked.

I sat there for a good half an hour, hand-stitching the quilt binding, watching television and telling myself that it could be worse, that my life could be as messed up as the people on the reality show reruns—trapped in a house, or on an island, or in a French château with a bunch of people who you didn’t know that well but who, somehow, knew way too much about your personal weaknesses and weren’t afraid to talk about them.

When I picked up the phone and my parents started to sing “Happy Birthday” into the line, I remembered that being part of a family is pretty much the same thing.

“I’m fine. Really. Everything is fine.”

“Margot,” Dad said in his rumbling bass, “don’t use that tone with your mother.”

I forced myself to smile, hoping this would make me sound more cheerful than I felt. “I wasn’t using a tone, Daddy. I was answering Mom’s question. I’m fine.”

My mother sighed. “You’ve been so secretive lately, Margot.”

Dad let out an impatient snort. “It’s almost as bad as trying to talk to Mari.”

At the mention of my sister’s name, Mom, in a voice that was half-hopeful and half-afraid to hope, asked, “Is she still planning on coming for Christmas?”

“She’s looking forward to it.”

Looking forward to it was probably stretching the truth, but last time I talked to my sister she had asked for suggestions on what to get the folks for Christmas. That indicated a kind of anticipation on her part, didn’t it?

“She’ll probably come up with some last-minute excuse,” Dad grumbled.

In the background, I could hear a jingle of metal. When Dad is agitated, he fiddles with the change in his pockets. I had a mental image of him pacing from one side of the kitchen to the other, the phone cord tethering him to the wall like a dog on a leash. Dad is a man of action; long phone conversations make him antsy.

“Wonder what it’ll be this time? Her car broke down? Her boss won’t let her off work? Her therapist says the tension might upset Olivia? As if spending a day with us would scar our granddaughter for life. Remember when she pulled that one, honey?”

A sniffle and a ragged intake of breath came from the Buffalo end of the line.

“Oh, come on now, Lil. Don’t cry. Did you hear that? Margot, why do you bring these things up? You’re upsetting your mother.”

“I’m sorry.” I was too. I hadn’t brought it up, but I hate it when my mother cries.

“I just don’t know why you’re keeping things from us,” Mom said.

“I’m not keeping anything from you. But at my age, I don’t think I should be bothering you with all my little problems, that’s all.”

I heard a snuffly bleating noise, like a sheep with the croup, and pictured my mother on her big canopy bed with her shoes off, leaning back on two ruffled red paisley pillow shams, the way she does during long phone conversations, pulling a tissue out of the box with the white crocheted cover that sat on her nightstand, and dabbing her eyes.

“Since when have we ever considered you a bother? You’re our little girl.”

“And you always will be,” Dad said. “Don’t you ever forget that, Bunny.”

Bunny is my father’s pet name for me—short for Chubby Bunny. My pre-teen pudge disappeared twenty-five years ago when my body stretched like a piece of gum until I reached the man-repelling height of nearly six feet. I haven’t been a Chubby Bunny for a quarter century, but Dad never seemed to notice.

“It’s Arnie, isn’t it? Is he seeing someone else?”

Mom didn’t wait for me to answer her question, but she didn’t have to. Somehow she already knew. How is that possible? Is that just part of being a mother?

“Don’t you worry, Margot. Arnie Kinsella isn’t the only fish in the sea.”

“Maybe not. But all the ones I haul into my boat seem to be bottom feeders.”

“Stop that. You can’t give up,” Dad said with his usual bull moose optimism and then paused, as if reconsidering. “You still look pretty good … for your age.”

Ouch.

“You know what I think?” he asked in a brighter tone before answering his own question. “I think maybe your husband’s first wife hasn’t died yet.”

“Werner!” My mother gasped, but why? Was she really surprised?

“What?” Dad sounded genuinely perplexed. “At her age, a nice widower is probably her best shot at getting a husband. I’m just saying …”

“Hey, guys, it’s sweet of you to call, but I need to get ready to go.”

“Are you going out with friends? Are they throwing you a party?” Mom asked hopefully and I knew she was wondering if my friends had thought to invite any bachelors to the celebration.

“I’ve got a meeting.” Not for two hours, but they didn’t need to know that.

“On your birthday?” Dad scoffed. “Margot, they don’t pay you enough at that quilt shop to make you go to meetings after hours. I keep telling you to get a real job.”

Yes, he does. Every chance he gets.

I used to have a “real job” according to Dad’s definition. I worked in the marketing department of a big company in Manhattan, made a lot of money, had profit sharing, a 401(k), and health insurance, which I needed because I was forever going to the doctor with anemia, insomnia, heart palpitations—the full menu of stress-related ailments. After I moved to New Bern and started working in the quilt shop, all that went away. Insurance and a big paycheck aren’t the only benefits that matter—I’ve tried to explain that to Dad. But there’s no point in going over it again.

“It’s a church meeting. I’m on the board now. Remember?”

“Oh. Well, that’s different, then.”

My parents are very active in their church. Mom has taught fourth grade Sunday school since 1979. When there’s a snowstorm, Dad plows the church parking lot with the blade he keeps attached to the front of his truck and shovels the walkways. No one asks him to do it; he just does. That’s the way my folks are. They’re good people.

“What a shame they scheduled the board meeting on your birthday,” Mom said.

“This is kind of an emergency thing. We’ve got to pick a new minister to fill in while Reverend Tucker is recovering.”

“Oh, yes,” she said, remembering our last conversation. “How is he?”

“Better, I think. I’ll find out more tonight. Anyway, I’ve got to run. Love you.” I puckered my lips and made two kiss noises into the phone.

“Love you too, sweetheart. Happy birthday! If that sweater doesn’t fit, just take it back. But promise me you’ll at least try it on before you return it.”

“I’m not going to return it.”

“Well, there’s a gift receipt with the card if you do.”

Dad cleared his throat. “And there’s a hundred-dollar bill in there too. That’s from me. Buy yourself something nice.”

“Thanks, Dad. But you didn’t have to do that.”

“Why not? Can’t a father spoil his daughter on her birthday? After all,” he chuckled, “you only turn forty once.”

Thank heaven for that.

“I don’t care how old you are, Bunny. Don’t forget, you’re still our little girl.”

As if I could. As if they’d ever let me.

After I hung up, I went back to work on the quilt. This time I left the television off and just focused on the stitches, trying to make them small and even. It’s a very soothing thing to stitch a binding by hand, almost meditative. With my tears over Arnie spent, I turned my thoughts, both hopeful and anxious, to Christmas, and my sister.

Mari’s full name is Mariposa. That means “butterfly” in Spanish, so when a bolt of fabric with butterflies in colors of sapphire, teal, purple, and gold on a jet-black background came into the shop, I made two important decisions—I would use it to make a quilt for Mari and I would invite her and my parents to come for Christmas.

It’s been five years since the last time we tried it. Olivia, my niece, was only a few months old. I’d seen the baby a couple of times, but my parents had never met their granddaughter. There is a lot of bad blood between my sister and parents. I talked Mari into coming to Buffalo for the holidays, but at the last minute she called and canceled. Mom was crushed and cried. Dad and Mari got into a shouting match. It was awful. Mari blamed me. It was almost a year before she’d answer my phone calls again.

That’s why making a second attempt at bringing the family together for Christmas really was a big decision, but I had to do it. When I saw those sapphire blue butterflies, the exact blue of Mari’s eyes, I knew I had to take the chance and at least try. Honestly, I didn’t really expect Mari to say yes. At first, she didn’t.

“No, Margot,” she snapped, almost before the words were out of my mouth. “I am never going back to Buffalo. Too many bad memories.”

“No, no. Not Buffalo. I didn’t say that. Come here, to New Bern.”

In truth, I had been thinking we’d get together at Mom and Dad’s, but perhaps things would go more smoothly if we met on neutral ground.

“New Bern is beautiful at Christmas. There’s a huge decorated tree on the Green and they outline all the buildings with white lights. You and Olivia can stay here and I’ll reserve a room for Mom and Dad at the inn.”

Would the inn already be booked for Christmas? It didn’t matter. I talked as fast as I could, spinning out a vision of the perfect Christmas, making it all up as I went.

“My friends, Lee and Tessa, have a farm outside of town where we can cut our own tree. Lee just refurbished an old horse-drawn sleigh. I bet Olivia has never been in a sleigh! And the quilt shop has an open house on Christmas Eve with cookies and punch and presents. Everyone will make the biggest fuss over Olivia, you’ll see. I’ll ask Charlie, Evelyn’s husband, to dress up as Santa Claus and deliver her presents!”

Would Charlie agree to that? I’d get Evelyn to ask him. He’d do it for her.

“And after the open house we can decorate the tree together and go to the midnight service at church, all of us together, the whole family, and …”

“No, Margot … just. Wait. Give me a second to think.”

I clamped my lips shut, closed my eyes, said a prayer.

After a long minute, Mari said, “I don’t know, Margot. It’s just … we have plans for Christmas Eve. Olivia is going to be a lamb in the church nativity play.”

“Oh, Mari! Oh, I bet she’s adorable!”

“She is pretty sweet,” she said in a voice that sounded like a smile. “I had to rip out the stupid ears on the costume three times, but it turned out so cute.”

“I’d love to see her in it. I bet Mom and Dad would too. Would you rather we all came to Albany for Christmas?”

“Nooo,” Mari said, stretching out the word for emphasis. “Very bad idea. Too much, too soon. But … what if we just came for Christmas dinner, just for the afternoon? I think that’s about all I can handle this time.”

This time? Did that mean she thought there might be other times too? I was dying to ask, but didn’t. She was probably right. After so many years apart and so many resentments, an afternoon together was probably as much as anyone could handle.

It was a start. Sometimes, that’s all you need—a decision, a second chance.

Sitting quietly and sewing that bright blue binding inch by inch to that border of brilliant, fluttering butterflies, covering all the uneven edges and raveled threads with a smooth band of blue, seeing all those different bits and scraps of fabric come together, stitch by stitch, into a neatly finished whole helped me look at things differently.

Coming upon Arnie and Kiera in the restaurant was a blessing in disguise, I decided, an opportunity to change my outlook, a chance to quit feeling sorry for myself and find peace and purpose in my life as it was, not as I wished it to be. I came to this conclusion just as I placed the final firm stitch in the edge of the binding. When I was done, I spread the quilt out on the floor.

It would have been easy enough to create a pretty pieced quilt using the butterfly focal fabric. Every quilt I’ve made has been a variation on that theme, but this time I wanted to try my hand at appliqué. Having taken that leap of faith, I decided to go one step further and create my own design. And rather than planning out every little detail of the quilt, I decided to gather up my fabrics and just “go with the flow,” letting inspiration come to me as it would, leaving myself open to the possibility of new ideas and insights.

The center medallion, which I’d come to think of as “the cameo,” was an ink-black oval appliquéd with flowers and leaves and fat curlicues, like dewdrops splashing on petals, all drawn by me, in teal, cobalt, azure, butterscotch, honey, and goldenrod, colors I’d picked up from the butterfly wings. The cameo was framed by curving swaths of sunshine yellow, making the oval into a rectangle. Next, I built border upon border upon border around the edges of the rectangle to create a full-sized quilt; three plain butterfly borders, of varying widths, and the same number and sizes of sawtooth and diamond borders, one with the diamonds all in yellow, another all in blue, a third with colors picked at random, and a thin band of black to make those brilliant colors even more vibrant. Finally, I dotted the top with individual appliquéd butterflies “fussy-cut” from the focus fabric and placed here and there on and near the cameo and borders.

That idea had come to me at the last moment, but it made a world of difference. It was almost as if a migration of butterflies had seen the quilt from the air and come to light gently upon the smooth expanse of cloth, taking a moment of respite in that rich and lovely garden of color before going on their way. That’s how I felt looking at it, rested and renewed, hopeful, ready to rise again and resume the journey.

It was the most beautiful quilt I’d ever made, and it had come about all because I’d been willing to lay aside my old habits and leave myself open to new possibilities. There was a lesson in that.

God had something new in mind for me, something better, I was sure of that. And, though I can’t tell you how, I was sure it had something to do with my family, my sister, my niece. If I was never to have children of my own, perhaps I was to play a role in Olivia’s life? I barely knew her, but I longed to shower my little niece with love, to regain my sister’s friendship and heal the wounds that had torn us apart.

Maybe this would be the year that we could all finally put the past behind us. Maybe this Christmas would be the moment and means to let bygones be bygones, the year we would finally cover all the raveled edges and loose threads of the past and be a family again, bound by blood, tied with love, warts and all.

Maybe.

The church vestibule was cold and a little gloomy. The big overhead chandeliers were dark so the only light came from a few low-watt faux-candle wall sconces topped with tiny gold lamp-shades. Though the sanctuary had been decked for Christmas more than two weeks before, the clean, sharp scent of cedar and pine boughs hung in the air. That’s the upside of an unreliable furnace; chilly air keeps the greens fresh longer.

Abigail stood on the mat and stamped the snow off her boots. “We’re late,” she said in a slightly accusing tone, nodding toward a trail of melting slush left by those who had arrived first.

It wasn’t my fault. Abigail left me cooling my heels in her foyer for ten minutes while she was in the kitchen giving Hilda, her housekeeper, last-minute instructions about Franklin’s dinner. I almost reminded her of that, but then thought better of it. I’ve known Abigail long enough to know she doesn’t mean to sound snappish. She just hates being late. When you think about it, it’s kind of sweet that she fusses over Franklin’s dinner like that, as though they’d been married three months instead of three years.

If I ever get married, that’s just how I’d want to treat my husband, as though we were newlyweds forever. I wish …

I stopped myself. I wasn’t going to go there. I was going to stick to my resolution, be content in every situation. And what was so bad about my situation anyway? Things could certainly be much worse. Think of poor Reverend Tucker, lying in a hospital bed.

“Have you heard any more about Reverend Tucker?” I asked as I followed Abigail down the stairs. “Mr. Carney made it sound pretty bad.”

“Ted likes to make things sound bad,” Abigail puffed. “Makes him feel important to get everyone else in a flutter. There’s no such thing as a good heart attack, but Bob will be fine. I called the hospital and pried some information out of the administrator.”

I’ll bet you did. I smiled to myself. Abigail is one of the biggest donors to the hospital and about fifty other charities. She has clout in New Bern and no qualms about exercising it on behalf of people she cares about.

“I insisted that they put the same doctor who treated Franklin on the case. He’s the best cardiac man in the state. Don’t worry, Margot. After a few months of rest and rehabilitation, the good reverend will be back to his old self.”

“That’s a relief. I can’t imagine anyone else being able to fill his shoes.”

“Nor can I. But we will have to find someone to replace him, at least . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...