- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

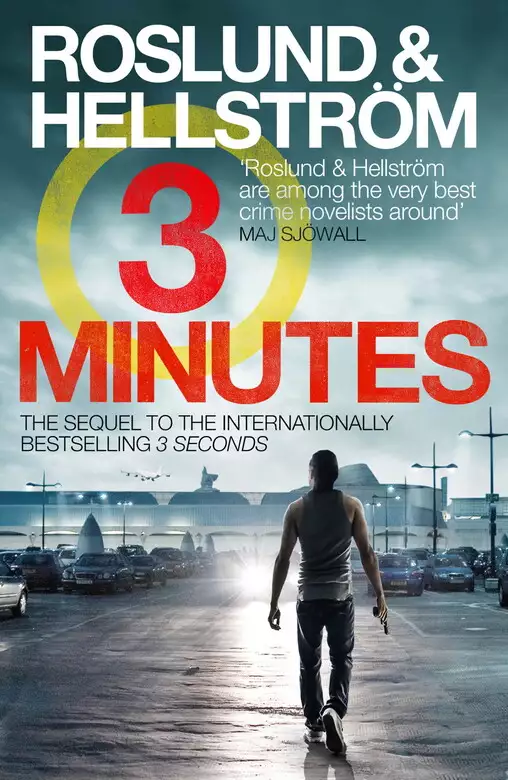

Synopsis

One-time government agent Piet Hoffmann is on the run: both from the life prison sentence he escaped, and from the Polish drug mafia he double-crossed. Only Hoffmann's handler, Erik Wilson, knows he now hides in Calí, Colombia, living under a false identity with his wife Zofia and sons Rasmus and Hugo.

But life on the run is precarious. And so when Hoffmann, in order to survive, accepts employment as a bodyguard and hit man for the Colombian cocaine mafia, and is simultaneously approached by the US DEA to infiltrate the same cartel, he chooses to say yes to both. Hoffmann has a new, lucrative double life.

However, Hoffmann's successful balancing act is short lived. When Timothy D Crouse, Chairman of the US House of Representatives, is kidnapped while on a trip to Colombia, US forces settle on a new enemy for their next War on Terror. This gives the cartel and the US government the same problem. Piet Hoffmann.

Condemned and hung out to dry by both sides, Hoffmann is stranded. Yet help will come from the most unlikely of figures - the stubborn, ascerbic Swedish detective who has doggedly tracked his whereabouts. DCI Ewert Grens - the enemy who Hoffmann once tricked - will now become the only ally he can trust.

Release date: July 27, 2017

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 496

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Three Minutes

Anders Roslund

Hot, like yesterday, like tomorrow. But easy to breathe. It rained recently, and he takes a deep, slow breath and holds the air inside, lets it lie there in his throat before releasing it a little bit at a time.

He exits a city bus that was once painted red, and which departed just an hour ago from a bus stop in San Javier, Comuna 13 – a few high-rises and some low-rises, as well as buildings that aren’t entirely walled in. Some call it an ugly neighbourhood, but he doesn’t agree, he lives there, has lived there for the entirety of his nine years. And it smells different. Not like here, in the city centre. Here the scent is unfamiliar – exciting. A large square that has probably always been here. Just like the fish stalls and meat stalls and vegetable stands and fruit stands and the tiny restaurants with only three or four seats. But all these people crowding around, jostling each other, surely they haven’t always been here? People are born, after all, and die – they’re replaced. Right now he sees the ones that exist, but by the time he grows up some of those will be gone and new ones will have arrived. That’s how it works.

Camilo crosses the square through narrow aisles and continues into La Galería. Here there are even more people. And it’s a little dirtier. But still lovely with all those apples and pears and bananas and peaches lying in heaps, changing colours. He collides with an older man who swears at him. Then he walks a little too close to the bunches of big, blue grapes and some fall to the ground. He picks them up and eats as many as he can before a woman who resembles his mother starts screaming the same curses that the older man just screamed at him. But he doesn’t hear them, he’s already moved on to the next stall and the next and the next. And when he passes by the last stalls of fish and long since melted ice – and here the smell is not exciting, dead fish don’t like the heat and the ones that haven’t sold by lunch smell even worse – he knows he’s almost there. A few more steps and there they are. Sitting on wooden benches and wooden chairs in front of the heavy tables that don’t belong to the merchants or the kitchens, which someone put at the far end of the market, where everything really has run out. That’s what they do, sit and wait together. He hasn’t been here that many times, he’s only nine years old. But he does as they do – sits down and waits and hopes that today, today he’ll get a mission. He never has before. The others are a little older – ten, eleven, twelve, thirteen, a few even as old as fourteen, their voices are starting to drop, cutting through the air and occasionally losing grip, falling out of their mouths and fluttering here and there just when they’re about to speak. He wants to be like them, earn money like them. Like Jorge. His brother. Who is seven years his elder. Who was seven years his elder, he’s dead now. The police came to their home, rang the doorbell and told his mother that a body had been found in Río Medellín. They thought it might be him. They wanted his mother to come with them and identify him. She had. He hadn’t been in the water long enough to become unrecognisable.

‘Hi.’

Camilo greets them timidly, so timidly that they don’t even notice, or at least it seems so to him. He sits at the very edge of one of the benches where the other nine-year-olds are sitting. He comes here every day after school. The voices that cut the air, who’ve been here longer, don’t go to school at all, nobody forces them to, so they sit here all day. Waiting. Talking. Laughing sometimes. But meanwhile they keep glancing at the space between the last stalls – cauliflower and cabbages like soft footballs piled up on one side and large fish with staring eyes on the other – glancing, but pretending they don’t care at all. And everyone knows. Everybody knows they’re fooling each other and still everybody pretends their eyes aren’t glancing in that direction, when that’s all they’re actually doing. Because that’s the direction they usually come from. So you have to be ready. Clientes. That’s what they call them.

Camilo takes a deep breath and can feel a cloud forming in his belly, white and fluffy and light. And a kind of pleasure fills his whole body, his heart beats faster, and the red on his cheeks deepens.

Today.

He wants it so much.

He’s known since this morning. Today somebody is going to give him his very first mission. After today, he’ll have done it. And once you’ve done it, you’re for ever somebody else.

It’s hotter now. But still easy to breathe. A city that’s fifteen hundred metres above the sea, and when people come just for the day, as customers often do, they complain about the lack of oxygen, their lungs seize up, and they swallow again and again trying to get more.

There. There.

A cliente.

Camilo sees him at the exact same time as everybody else. And he perks up just like everybody else, stands up, and hurries towards him, flocking around him. A fat man with no hair wearing a black suit and black hat with small, sharp eyes like a bird. The man examines the kids flocking around him and after a fraction of a second, as intense as the beating of a drum, he points to someone in the middle. Someone who’s eleven, almost twelve, who’s done this before. And they go off together.

Shit.

Camilo swallows what might be a sob. Shit, shit, shit. That might be the only one who comes today.

And he’d been so sure it was his turn.

An hour passes. Then another. He yawns, decides not to blink an eye, counts how many times he can raise and lower his left arm in sixty seconds, sings the kind of silly children’s song that gets stuck in your head.

Nothing today, either. Except waiting.

Someone is coming.

He’s sure of it.

Determined steps. Headed straight for them.

Someone is coming.

And everybody does exactly like last time, like always, jumping up, flocking around him, fighting to be seen.

A man this time too. Powerfully built, not fat like the other one, but big. An Indian. Or maybe not. Mestizo. Camilo recognises him. He’s seen him here before. He comes all the way from Cali, and he’s older than Camilo’s father. Or he thinks so anyway, he’s never seen his father and his mother won’t say much about him. The Indian, or Mestizo, usually gives his missions to Enrique – Enrique who hasn’t been around for a while, who’s done this a total of seventeen times.

They are all filled with expectation. Usually no more than a few come here with a mission, and this is probably today’s last chance before they all have to head home having accomplished nothing more than waiting. They surround the Mestizo, and he watches them try to look like adults.

‘You’ve all done this before?’

They all answer simultaneously.

‘Sí!’

Everyone but Camilo. He can’t raise his hand and say yes, can’t lie. The others shout: eight times and twelve times and twenty-one times. Until the man looks at him.

‘What about you?’

‘Never. Or . . . not yet.’

Camilo is sure of it, the Mestizo is staring only at him.

‘Well then, it’s time for your first. Right now.’

Camilo stretches as high as he can, while trying to take in what the man just said. It’s true. He’s going to do it. Today. And tomorrow, when he walks through those rows of stalls, everything will have changed, they will look at him with respect, because he’ll have done it.

The car is illegally parked outside La Galería, near the square. A Mercedes G-Wagen. Black. Boxy. Large floodlights on the roof – Camilo counts four – broad and robust, which can be angled in different directions. Thick windows you can’t see into, not even through the windscreen. Bulletproof, he’s sure of it. And inside the car smells like animals, as new cars do. This one has soft, white leather seats. It hardly makes a sound as it starts up and rolls away. The Mestizo is at the wheel with Camilo in the passenger seat. He glances surreptitiously at the man who is so tall his head almost grazes the ceiling. Square face, square body, a bit like the car they’re sitting in. A squat, black braid of hair that resembles a burnt loaf of bread is tied back in a hairband woven with glistening gold threads. They don’t say a word to each other. It takes twenty minutes to drive to their destination as the city transforms from shabby to dirty to renovated to expensive and then back to shabby. Over the Carrera 43A and onto a smaller road that’s he’s unfamiliar with.

Then they stop. Camilo looks at the street signs, they have stopped where Carrera 32 crosses Calle 10. The city is expensive again. A neighbourhood called El Poblado that he’s never been to before. A good neighbourhood. His mother has said so. And of course, people live here in their own houses with their own lawns and two cars in the driveway, not far from the city centre.

From here, they can see the house without being seen. And the Mestizo points.

‘There. She’s standing in the far window. Your mission.’

Camilo sees her. And nods. Nods again when he’s given a towel and puts it on his lap, unfolds it. A handgun. A Zamorana, made in Venezuela, fifteen shots, nine millimetre. Camilo knows that. Jorge taught him almost everything.

‘And you know the rest, right? What to do?’

‘Yes.’

‘How to shoot?’

‘Yeah. I’ve done that a ton of times.’

They had, Jorge and Camilo. Practised. In the evenings they used to practise with the same kind of gun but an older version, which Jorge borrowed from a person Camilo was never allowed to meet. On a deserted lot quite far from here, in La Maiala.

‘Good. We’ll meet in two hours. Same place as before, at the market. You’ll have to get back there by yourself.’

His heart is hammering as much from joy as from expectation or excitement or fear.

A sicario.

After the car has disappeared, Camilo walks over to some trees that line the roadside and sits beneath one of them. From here he can observe the house and the window, and the woman standing there, clueless.

Green dress. Not as old as he’d thought. She’s framed by what appears to be the kitchen window, and he can’t really make out what she’s doing. He screws on the silencer just as Jorge taught him to do and loads the magazine with the five bullets that were also in the towel. That’s what they give you.

Focus.

That’s what Jorge used to say, Focus, little brother, keep breathing slowly, close your eyes, and think of something you like. Camilo thinks of a boat. He likes boats, big boats with sails that float forward slowly when the wind is slow and fast when the wind is fast. He’s never been on a boat, but he’s thought about it so much he’s sure he knows how it feels.

A few minutes. And he’s ready.

Stands up. Stuffs the gun into his waistband and makes sure his shirt covers it. Walks to the door of the house the Mestizo pointed to.

Bars. A security door. Extra thick. He’s seen this kind of door before.

And he rings the bell.

Steps. Someone is approaching. Someone is peeking through the peephole, he can tell from the shadow.

He pulls the gun out of his pants and pushes the small switch located at the far end of the grip, turns off the safety at the precise moment he hears her unfastening the door chain.

Then she opens the door, because she sees a nine-year-old child.

And he meets her eyes just like Jorge told him to and raises his gun, aiming upwards, she’s so much taller than him.

He holds it with both hands just like Jorge showed him.

And pulls the trigger.

Twice.

The first shot hits her chest and she jerks, bounces a little, and looks surprised, in her mouth and in her eyes. Then he shoots again, at her head.

And she sinks down, like a leaf gently falling from a tree, with her back against the doorframe and a bleeding hole in the middle of her forehead. But she doesn’t fall backwards or to the side, not like he’d imagined she would, like they do in movies.

He sits on the bus, afterwards. All the way back. And it feels like but a moment ago that his heart was pounding with joy and excitement, yet not at all like a moment ago – now there is no fear. Now he’s done it. It will show on him, he knows, he can see it himself on others.

The car is waiting at the same place. Near the square. The stocky Mestizo is in the front seat, the thick braid hanging on his shoulder. Camilo knocks on the window, and the passenger door opens.

‘Done?’

‘Done.’

The Mestizo wears gloves as he takes back the handgun and pulls out the magazine. There are three bullets left.

‘You used . . . two?’

‘Yes. One in the chest, one in the forehead.’

Me. A sicario.

The bus again. The back of the bus is full, and he sits down on the only free seat, which is right behind the bus driver. He returned the pistol in a towel and got two hundred dollars. Camilo’s cheeks feel hot, red. Two hundred dollars! In his right pocket! And the bills are as warm as his cheeks, burning his thigh as if they want to come out, show themselves to the other passengers on the bus this evening, who don’t have two hundred dollars in their pockets, not even combined.

Six zones along Rio Medellín turns into sixteen comunas and two hundred and forty-nine barrios. He is on his way to one of them a bit further up on the slopes of Comuna 13, San Javier. On his way home. He’s ridden this way so many times, with his mother and with Jorge and alone, but it’s never felt like it feels now. The cloud in his stomach is no longer moving back and forth, it’s made a place for itself next to his heart, and the fluffiness no longer presses out towards his chest, but inwards. He leans back against his hard seat and imagines his home, which is crowded and messy and full of sounds, how he’ll run there as fast as he can from the bus stop and rush inside and before he’s even seen her he’ll shout Mum, I told you I’d fix the fridge and I did, and he’ll hand her half the money. And she’ll beam with pride. And then he’ll go to the room they sleep in and to his secret spot – a flat tin box that once held thin pieces of chocolate and which he can hide almost anywhere – and he’ll put the other one-hundred-dollar bill in there, his first.

If dawn turns into morning. If July turns into August.

If an ending turns into a beginning.

Piet Hoffmann rolled down the windows of the truck – a draught – it wasn’t even eight in the morning yet, but the heat was already pressing against his temples, the shiny sweat covering his shaved head evaporating slowly as the wind whirred around him.

If an ending turns into a beginning and therefore never ceases.

It was on this day three years ago that he arrived in a country he never visited.

On the run.

A void.

Life was now just about survival.

He eased up on the throttle slightly, ninety kilometres per hour, just as they’d agreed. He checked the distance to the truck in front of him: two hundred metres, just as they’d agreed.

They had long since turned off highway 65. Kilometre after kilometre and to their left, on the other side of dense shrubbery, the Rio Caquetá flowed, roared, forming the border to the Putumayo Province – the river had followed them the last hour, keeping its distance but still stubbornly sticking to the road. He chewed on coca leaves to stay sharp, drank white tea to stay calm. And occasionally drank some of the mixture El Mestizo forced on him before every delivery, some version of colada: flour, water, sugar and a lot of Cuban espresso. It tasted like shit, but it worked, driving away hunger and fatigue.

On several occasions, especially during the last year, he’d believed the end really was an end, an opening, an opportunity to get back home. To Europe. Sweden and the Stockholm he and Zofia and Rasmus and Hugo considered the whole of their mutual world. And every time the opening quickly closed, the void had widened, their exile continued.

Tonight. He’d see them again. The woman he loved, even though he’d once believed he wasn’t capable of loving, and two small people that he somehow loved even more – real people who had real thoughts and looked at him like he knew things. He’d never intended to have any children of his own. But now when he tried to remember what it was like before they arrived, there was only blankness, as if the memories were gone.

He slowed down a little, he was getting too close. Maintain a constant distance, for maximum security. It was his responsibility to protect both of these trucks. They’d already paid for their passage through – this was the kind of place where if you joined the police or military, it wasn’t because you wanted to catch criminals or fight crime, it was because you wanted to make a good living collecting bribes.

Protection.

That’s what he did yesterday, was doing today, and would do tomorrow. Transport. People. As long as he did it better than anyone else, nobody would question him. If El Mestizo, or anyone else in the PRC guerrillas, doubted for even a moment that he was who he said he was, if he was exposed, it would mean instant death. For himself, for Zofia, for his children. He had to play this role every day, every second.

Piet Hoffmann rolled up the two side windows, the heat neutralised for a moment – the breeze had scared away the foaming wave of sweat that slipped beneath his usual get-up. The bulletproof vest with two pockets he’d sewn on himself – the GPS receiver that stored the exact coordinates of every route and destination, the satellite phone that worked even in the jungle. Plus the gun hanging from a shoulder holster, a Radom, fourteen bullets in its magazine, the one he’d got used to wearing during his many years of undercover work with the Polish mafia, paid for by the Swedish police. In the other shoulder holster, he carried a hunting knife with a wooden handle, which he liked to hold, its two-sided blade newly sharpened. He’d carried it for a long time, since before the judges and prison sentences, since before he’d worked for Swedish special protection – maximum damage with a single stab. On the seat next to him sat a Mini-Uzi with a rate of fire of nine hundred and fifty rounds per minute and a customised collapsible stock that was as short as he needed it to be. Also, on the platform, just behind the truck’s cab, secured with two hooks, he had a mounted sniper rifle. He even had registrations for all of them. Issued by El Cavo in Bogotá for the right price.

Over there. Beyond the unpainted shed that stood close to the road, just before the two tall trees that had long since died – naked and stripped branches that seemed to be waiting for someone who would never arrive. That was where they would slow down, turn right, and continue the last few kilometres down a muddy dirt road that was too narrow and whose deep potholes were filled with water. A fucking potato field. Thirty kilometres per hour, you couldn’t go faster than that. So Piet Hoffmann drove a little closer to the truck in front of him, half of the secure distance, never leaving a gap of more than one hundred metres.

He’d never transported anything to this particular cocina before. But they all looked alike anyway, all had the same purpose – processing coca leaves with chemicals in order to spit out over a hundred kilos of cocaine a week. About an hour along this godforsaken road, and they’d be in a PRC-controlled area – which had once been FARC-controlled – where labs are either owned by the PRC or by operators who rent their land from the PRC and pay to grow and produce. When he first got here, Hoffmann had assumed the mafia was in charge, that’s what he grew up with, that’s how myths were formed, took root. He knew now that wasn’t the case. The members of the mafia might rule in Colombia, might sit on the money, but without the owner of the jungle they were nothing. The mafia. The state. The paramilitary. And a mess of other organisations running around making war on each other. But there was no power without the PRC guerrillas – the cocaine demanded the jungle, demanded the coca leaf, and they weren’t cultivated on guerrilla land without guerrilla permission.

‘Hello.’

He’d planned on waiting to call. But he wanted it too much. Her hands on his cheeks, her eyes looking into his, wanting the best for him, loving, steadfast, beaming with confidence.

‘Hello.’

He’d been away for seven days. Like last time. That’s how it worked. Distance, waiting, long nights. He endured it because she did. They had no other choice. This was his only way to support them. If he went back to Sweden he’d be locked up. If he didn’t continue to play this role, he’d be dead.

‘I miss you.’

‘I miss you, too.’

‘Tonight. Or maybe even this afternoon. See you then.’

‘Love you.’

He was about to answer. Love you too. When the call cut off. That happened out here sometimes. He’d call again, later.

The already tiny road was becoming more like a path, narrower and narrower and with even wider potholes. It was difficult to maintain the correct distance. Sometimes the second truck disappeared around tight curves and behind high ridges. Hoffmann had just rocked the right rear wheel out of a crater when two brake lights lit up ahead of him, glowing like red eyes under the bright sun. It felt wrong. The other truck should not be slowing down, or stopping, not here, not now. He’d designed every detail of this transport himself, it was his responsibility, and he’d made it clear that no vehicle should slow down to less than twenty-five kph without warning him.

‘Watch out.’

El Mestizo’s voice in Piet Hoffmann’s ear, he adjusted the round and silvery receiver in order to hear better.

‘Stop.’

Hoffmann slowed too, then stopped just like El Mestizo. Eighty, maybe ninety metres away. And now he could see it, despite the sharp curve and bushes obscuring his view. In front of them on the road stood a dark green off-road vehicle. And on either side of it stood more. He counted four military vehicles in a semicircle, like a smile stretching from one edge of the jungle to the other.

‘Wait and—’

It crackled sharply, that electronic scraping turned angry and tore into his ear, and Hoffmann had a hard time making out the whole sentence as El Mestizo moved the pinhead microphone to his shirt collar and locked it into transmit mode.

Hoffmann kept the engine running while he gazed at those green vehicles. Regular military? They’d already been paid. Maybe paramilitary? If that was the case, they had a problem. They weren’t on El Mestizo’s payroll.

Then every cab opened at the same time. Men in green uniforms jumped out holding automatic weapons, but not pointing them.

And now he could see.

It wasn’t paramilitary. Those weren’t their uniforms. And he relaxed, somewhat. El Mestizo seemed to do the same, his voice became less of a growl, as it did when vigilance and suspicion took hold of him, the characteristics that defined him.

‘We know them. I’ll be back.’

Now the door to El Mestizo’s cab opened, too. He was heavy, tall and also wide, but when he landed on the muddy ground, he did so gently. Hoffmann had seldom seen so much body move with such coordination.

‘Captain Vásquez? What’s going on?’

The transmitter on his collar no longer crackled, instead transmitting clear and clean sound. Reproducing the overly long silence.

Until Vásquez threw his arms wide.

‘Going on . . .?’

‘These vehicles. It looks like a goddamn roadblock.’

‘Mmm. That’s exactly what it is.’

Vasquez’s voice. Piet Hoffmann didn’t like it. There was something missing. A resonance. It was the kind of voice a man unconsciously affected when he didn’t mean you well. Hoffmann rose up gently from the driver’s seat, exited through the cab’s rear window and crawled out onto the covered bed of the truck. The sniper rifle was held down by two simple brackets and he undid them, took out the bipod, lay down and pulled the bolt upwards and towards himself while pushing the muzzle through one of the prepared holes in the tarp.

‘You’ve been paid.’

‘Not enough.’

The telescopic sight brought him close. It was as if he was standing there with them, among them, El Mestizo on one side and Captain Vásquez on the other.

‘You got what you asked for, Vásquez.’

‘And it’s not enough.’

Close enough to be part of El Mestizo’s face. Or Johnny’s face, he called him that more and more often. Shiny, like always when they left Cali or Bogotá for the jungle, mouth tense, eyes on the hunt, eyes that had once frightened Piet, but that he’d learned to like even though they so often turned from friendly to ruthless. And Vásquez’s face – the bushy, pitch-black moustache that he was so proud of, eyebrows sprawled like wild antennas. He looked as usual. And not at all. Just like his voice, his movements were different, not heated, violent, more confident. Yes, that’s what they were, slow, almost transparent, as if he wanted what he said to really sink in. He hadn’t looked like that when they negotiated with him, paid him at a hole-in-the-wall restaurant behind a church in Florencia, compensation for allowing three deliveries to pass. On those occasions Vásquez wore civilian clothes, seemed nervous, talking and moving jerkily, only settling down after he ripped open the envelope and – mumbling – counted the money bill by bill.

‘You never told me how big your transport was. You didn’t tell the truth.’

‘We have an agreement.’

‘I didn’t know what it was worth. But I do now.’

Piet Hoffmann peered through the telescopic sight, focusing on El Mestizo’s eyes. He knew them well. They were about to change shape. It always happened just as fast – pupils dilating, gathering more light for more power, preparing to attack.

‘Are you joking? You’ve been paid.’

‘I want just as much – again.’

Vásquez shrugged his uniformed shoulders, pointed to the diagonal trucks and the four young men waiting outside them. And all of them simultaneously – without raising their weapons – put their right index finger on the trigger.

A clear signal.

Piet Hoffmann magnified the telescope on his rifle and moved the bullseye to the centre of Captain Vasquez’s forehead, aimed at the point between his eyebrows.

‘You got what you wanted.’

‘That’s what you think. But I don’t agree.’

‘Be damn careful, Il Capitano.’

Twenty-seven degrees outside. Hoffmann’s left hand on the rifle’s telescope. Windless. The small screw gently between his index finger and thumb. Distance ninety metres. He turned, one click.

TPR1. Transport right one.

Object in sight.

‘Be careful . . . you know as well as I do that accidents happen easily out here in the jungle. So listen very closely, Vásquez – you’re not getting any more money.’

Through the telescopic sight, Piet Hoffmann was almost a part of that thin skin, wrinkling up on the forehead, eyebrows drawing together. Captain Vásquez had just been threatened. And reacted.

‘In that case.’

What had been confidence and self-control now became aggression and attack.

‘I hereby confiscate your transport.’

Hoffmann felt it. They were on their way there. Where he didn’t want to go.

Right index finger lightly on the trigger.

Avoid all questions.

Survive.

His official duty was to protect. That was what El Mestizo believed and must continue to believe.

Breathe in through your nose, out through your mouth, the calm, it had to be in there somewhere.

He’d killed seven times before. Five times since he got here. Because the situation demanded it. To avoid being unmasked.

You or me.

And I care more about me than about you, so I choose me.

But the others had been the kind who profited directly from the drug trade, which slowly took away people’s lives. Captain Vásquez was just an ordinary officer in the Colombian army. A man who was doing what they all do, adapting to the system, accepting bribes as part of his salary.

‘So that means your truck is mine now . . .’

Vásquez was armed, an automatic rifle hanging off his left shoulder and a holster on his right hip, and that was the gun he pulled – a revolver he pressed against El Mestizo’s temple.

‘. . . and you’re under arrest.’

The captain’s voice had become much quieter, as if this was just between them, and that’s probably why the metallic click sounded so loud as the gun was cocked and the barrel rotated to release a new cartridge.

Breathe in, out.

Piet Hoffmann was there now, where everything could be broken down into its separate parts and built back up again. This was his world, and it made him feel secure. One shot, one hit. No unnecessary bloodshed. Take out the alpha, it worked every time, forcing everyone else to look around for where that shot came from, take cover.

‘Nobody puts a fucking gun to my head.’

El Mestizo spoke softly, almost a whisper, while turning around, even though the gun dug into the delicate skin of his temple – there’d be a round, red mark there later.

‘El Sueco.’

And now he looked straight at the second truck. At Hoffmann.

‘Now.’

One shot, one hit.

Piet Hoffmann squeezed the trigger a little more.

And I care more about me than about you, so I choose me.

And when the ball hit Captain Vásquez’s forehead it looked just like it always did with this ammunition – a small entrance wound, just

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...