- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

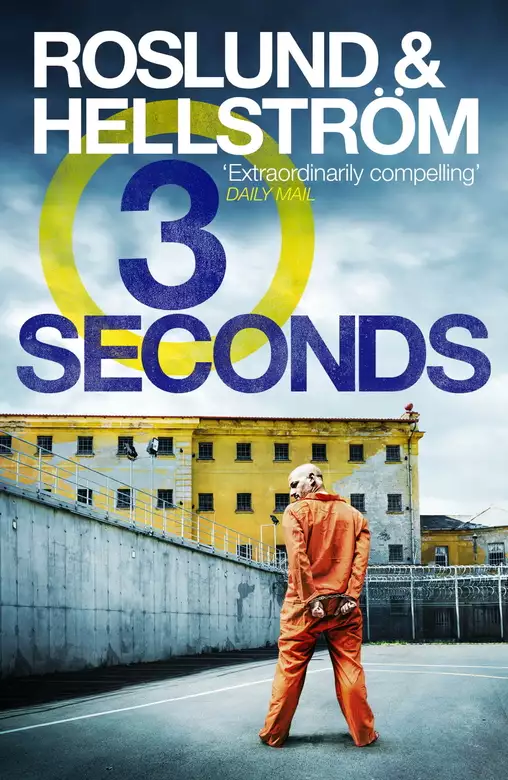

In this dark and gripping novel from #1 bestselling Swedish writing duo Roslund & Hellström, Piet Hoffman is the Swedish police's most valuable secret operative. His cover is that of a lieutenant inside the ruthless Polish mafia trying to take over amphetamine distribution within Sweden's prison system. With this, his most dangerous assignment, success will mean a new identity and the freedom to start a new life with his wife and young sons.

When a botched drug deal involving Hoffman results in the cold-blooded killing of a police informant, the investigation, assigned to the brilliant but haunted Detective Inspector Ewert Grens, leads to a string of unsolved cases in which key evidence has been withheld under mysterious circumstances. As Grens's investigation takes him closer to the truth, government lies are exposed and Hoffman is trapped in prison, wanted dead by both the police and the mafia. He has only one chance to make it out alive and start a new life. One chance and three seconds.

An audiobook with extraordinary insights and totally unexpected plots twists, Three Seconds is an intensely suspenseful thriller in which people in all positions of society are put to the test. Three Seconds was a #1 bestseller in Sweden and the winner of the Swedish Academy of Crime Writers' 2009 award for Best Swedish Crime Novel of the Year.

Release date: February 3, 2011

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 640

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Three Seconds

Anders Roslund

It was late spring, but darker than he thought it would be. Probably because of the water down below, almost black, a membrane covering what seemed to be bottomless.

He didn’t like boats, or perhaps it was the sea he couldn’t fathom. He always shivered when the wind blew as it did now and Świnoujście slowly disappeared. He would stand with his hands gripped tightly round the handrail until the houses were no longer houses, just small squares that disintegrated into the darkness that grew around him.

He was twenty-nine years old and frightened.

He heard people moving around behind him, on their way somewhere, too; just one night and a few hours’ sleep, then they would wake in another country.

He leant forward and closed his eyes. Each journey seemed to be worse than the last, his mind and heart as aware of the risk as his body; shaking hands, sweating brow and burning cheeks, despite the fact that he was actually freezing in the cutting, bitter wind. Two days. In two days he’d be standing here again, on his way back, and he would already have forgotten that he’d sworn never to do it again.

He let go of the railing and opened the door that swapped the cold for warmth and led onto one of the main staircases where unknown faces moved towards their cabins.

He didn’t want to sleep, he couldn’t sleep – not yet.

There wasn’t much of a bar. M/S Wawel was one of the biggest ferries between northern Poland and southern Sweden, but all the same; tables with crumbs on, and chairs with such flimsy backs that it was obvious you weren’t supposed to sit there for long.

He was still sweating. Staring straight ahead, his hands chased the sandwich round the plate and lunged for the glass of beer, trying not to let his fear show. A couple of swigs of beer, some cheese – he still felt sick and hoped that the new tastes would overwhelm the others: the big, fatty piece of pork he’d been forced to eat until his stomach was soft and ready, then the yellow stuff concealed in brown rubber. They counted each time he swallowed, two hundred times, until the rubber balls had shredded his throat.

‘Czy podać panu coś jeszcze?’

The young waitress looked at him. He shook his head, not tonight, nothing more.

His burning cheeks were now numb. He looked at the pale face in the mirror beside the till as he nudged the untouched sandwich and full glass of beer as far down the bar as he could. He pointed at them until the waitress understood and moved them to the dirty dishes shelf.

‘Postawić ci piwo?’ A man his own age, slightly drunk, the kind who just wants to talk to someone, doesn’t matter who, to avoid being alone. He kept staring straight ahead at the white face in the mirror, didn’t even turn round. It was hard to know for sure who was asking and why. Someone sitting nearby pretending to be drunk, who offered him a drink, might also be someone who knew the reason for his journey. He put twenty euros down on the silver plate with the bill and left the deserted room with its empty tables and meaningless music.

He wanted to scream with thirst and his tongue searched for some saliva to ease the dryness. He didn’t dare drink anything, too frightened of being sick, of not being able to keep down everything that he’d swallowed.

He had to do it, keep it all down, or else – he knew the way things worked – he was a dead man.

He listened to the birds, as he often did in the late afternoon when the warm air that came from somewhere in the Atlantic retreated reluctantly in advance of another cool spring evening. It was the time of day he liked best, when he had finished what he had to do and was anything but tired and so had a good few hours before he would have to lie down on the narrow hotel bed and try to sleep in the room that was still only filled with loneliness.

Erik Wilson felt the chill brush his face, and for a brief moment closed his eyes against the strong floodlights that drenched everything in a glare that was too white. He tilted his head back and peered warily up at the great knots of sharp barbed wire that made the high fence even higher, and had to fight the bizarre feeling that they were toppling towards him.

From a few hundred metres away, the sound of a group of people moving across the vast floodlit area of hard asphalt.

A line of men dressed in black, six across, with a seventh behind.

An equally black vehicle shadowed them.

Wilson followed each step with interest.

Transport of a protected object. Transport across an open space.

Suddenly another sound cut through. Gunfire. Someone firing rapid single shots at the people on foot. Erik Wilson stood completely still and watched as the two people in black closest to the protected person threw themselves over said person and pushed them to the ground, and the four others turned towards the line of fire.

They did the same as Wilson, identified the weapon by sound.

A Kalashnikov.

From an alleyway between two low buildings about forty, maybe fifty metres away.

The birds that had been singing a moment ago were silent; even the warm wind that would soon become cool, was still.

Erik Wilson could see every movement through the fence, hear every arrested silence. The men in black returned the fire and the vehicle accelerated sharply, then stopped right by the protected person, in the line of fire that continued at regular intervals from the low buildings. A couple of seconds later, no more, the protected body had been bundled into the back seat of the vehicle through an open door and disappeared into the dark.

‘Good.’

The voice came from above.

‘That’s us done for this evening.’

The loudspeakers were positioned just below the huge floodlights. The president had survived this evening, once again. Wilson stretched, listened. The birds had returned. A strange place. It was the third time he had visited the Federal Law Enforcement Training Centre, or the FLETC, as it was called. It was as far south in the state of Georgia as it was possible to go; a military base owned by the American state, a training ground for American police organisations – the DEA, ATF, US Marshals, Border Patrol, and the people who had just saved the nation once more: the Secret Service. He was sure of it as he studied the floodlit asphalt: it was their vehicle, their people and they often practised here at this time of day.

He carried on walking along the fence, which was the boundary to another reality. It was easy to breathe – he’d always liked the weather here, so much lighter, so much warmer than the run-up to a Stockholm summer, which never came.

It looked like any other hotel. He walked through the lobby towards the expensive, tired restaurant, but then changed his mind and carried on over to the lifts. Made his way up to the eleventh floor which for some days or weeks or months was the shared home of all course participants.

His room was too warm and stuffy. He opened the window that looked out over the vast practice ground, peered into the blinding light for a while, then turned on the TV and flicked through the channels that were all showing the same programme. It would stay on until he went to bed, the only thing that made a hotel room feel alive.

He was restless.

The tension in his body spread from his stomach to his legs to his feet, forcing him up off the bed. He stretched and walked over to the desk and the five mobile phones that lay there neatly in a row on the shiny surface, only centimetres apart. Five identical handsets between the lamp with the slightly over-large lampshade and the dark leather blotting pad.

He lifted them up one by one and read the display screen. The first four: no calls, no messages.

The fifth – he saw it before he even picked it up.

Eight missed calls.

All from the same number.

That was how he’d set it up. Only calls from one number to this phone. And only calls to one number from this phone.

Two unregistered, pay-as-you-go cards that only phoned each other, should anyone decide to investigate, should anyone find their phones. No names, just two phones that received and made calls to and from two unknown users, somewhere, who couldn’t be traced.

He looked at the other four that were still on the desk. All with the same set-up: they all were used to call one unknown number and they were all called from one unknown number.

Eight missed calls.

Erik Wilson gripped the phone that was Paula’s.

He calculated in his head. It was past midnight in Sweden. He rang the number.

Paula’s voice.

‘We have to meet. At number five. In exactly one hour.’

Number five.

Vulcanusgatan 15 and Sankt Eriksplan 17.

‘We can’t.’

‘We have to.’

‘Can’t do it. I’m abroad.’

Deep breath. Very close. And yet hundreds of miles away.

‘Then we’ve got a bastard of a problem, Erik. We’ve got a major delivery coming in twelve hours.’

‘Abort.’

‘Too late. Fifteen Polish mules on their way in.’

Erik Wilson sat down on the edge of the bed, in the same place as before, where the bedspread was crumpled.

A major deal.

Paula had penetrated deep into the organisation, deeper than he’d ever heard of before.

‘Get out. Now.’

‘You know it’s not that easy. You know that I’ve got to do it. Or I’ll get two bullets to the head.’

‘I repeat, get out. You won’t get any back-up from me. Listen to me, get out, for Christ’s sake!’

The silence when someone hangs up mid-conversation is always deeply unnerving. Wilson had never liked that electronic void. Someone else deciding that the call was over.

He went over to the window again, searching in the bright light that seemed to make the practice ground shrink, nearly drown in white.

The voice had been strained, almost frightened.

Erik Wilson still had the mobile phone in his hand. He looked at it, at the silence.

Paula was going to go it alone.

He had stopped the car halfway across the bridge to Lidingö.

The sun had finally broken through the blackness a few minutes after three, pushing and bullying and chasing off the dark, which wouldn’t dare return now until late in the evening. Ewert Grens wound down the window and looked out at the water, breathing in the chill air as the sun rose into dawn and the cursed night retreated and left him in peace.

He drove on to the other side and across the sleeping island to a house that was idyllically perched on a cliff with a view of the boats that passed by below. He stopped in the empty car park, removed his radio from the charger and attached a microphone to his lapel. He had always left it in the car when he came to visit her – no call was more important than their time together – but now, there was no conversation to interrupt.

Ewert Grens had driven to the nursing home once a week for twenty-nine years and had not stopped since. Even though someone else lived in her room now. He walked over to what had once been her window, where she used to sit watching the world outside, and where he sat beside her, trying to understand what she was looking for.

The only person he had ever trusted.

He missed her so much. The damned emptiness clung to him, he ran through the night and it gave chase, he couldn’t get rid of it, he screamed at it, but it just carried on and on … he breathed it in, he had no idea how to fill such emptiness.

‘Superintendent Grens.’

Her voice came from the glass door that normally stood open when the weather was fine and all the wheelchairs were in place around the table on the terrace. Susann, the medical student who was now, according to the name badge on her white coat, already a junior doctor. She had once accompanied him and Anni on the boat trip round the archipelago and had warned him against hoping too much.

‘Hello.’

‘You here again.’

‘Yes.’

He hadn’t seen her for a long time, since Anni was alive.

‘Why do you do it?’

He glanced up at the empty window.

‘What are you talking about?’

‘Why do you do this to yourself?’

The room was dark. Whoever lived there now was still asleep.

‘I don’t understand.’

‘I’ve seen you out here twelve Tuesdays in a row now.’

‘Is there a law against it?’

‘Same day, same time as before.’

Ewert Grens didn’t answer.

‘When she was alive.’

Susann took a step down.

‘You’re not doing yourself any favours.’

Her voice got louder.

‘Living with grief is one thing. But you can’t regulate it. You’re not living with grief, you’re living for it. You’re holding on to it, hiding behind it. Don’t you understand, Superintendent Grens? What you’re frightened of has already happened.’

He looked at the dark window, the sun reflecting an older man who didn’t know what to say.

‘You have to let go. You have to move on. Without the routine.’

‘I miss her so much.’

Susann went back up the steps, grabbed the handle of the terrace door and was about to shut it when she stopped halfway, and shouted: ‘I never want to see you here again.’

It was a beautiful flat on the fourth floor of Västmannagatan 79. Three spacious rooms in an old building, high-ceilinged, polished wooden floors, and full of light, with windows that faced out over Vanadisvägen as well.

Piet Hoffmann was in the kitchen. He opened the fridge and took out yet another carton of milk.

He looked at the man crouching on the floor with his face over a red plastic bowl. Some little shit from Warsaw: petty thief, junkie, spots, bad teeth, clothes he’d been wearing for too long. He kicked him in the side with the hard toe of his shoe and the evil-smelling prick toppled over and finally threw up. White milk and small bits of brown rubber on his trousers and the shiny kitchen floor, some kind of marble.

He had to drink more. Napij się kurwa. And he had to throw up more.

Piet Hoffmann kicked him again, but not so hard this time. The brown rubber round each capsule was to protect his stomach from the ten grams of amphetamine and he didn’t want to risk even a single gram ending up somewhere it shouldn’t. The fetid man at his feet was one of fifteen prepped mules who in the course of the night and morning had carried in two thousand grams each from Świnoujście, onboard M/S Wawel, then by train from Ystad, without knowing about the fourteen others who had also entered the country and were now being emptied at various places in Stockholm.

For a long time he had tried to talk calmly – he preferred it – but now he screamed pij do cholery as he kicked the little shit, he had to damn well drink more from the bloody milk carton and he was going to fucking pij do cholery throw up enough capsules for the buyer to check and quality-assure the product.

The thin man was crying.

He had bits of puke on his trousers and shirt and his spotty face was as white as the floor he was lying on.

Piet Hoffmann didn’t kick him any more. He had counted the dark objects swimming around in the milk and he didn’t need any more for the moment. He fished up the brown rubber: twenty almost-round balls. He pulled on some washing up gloves and rinsed them under the tap, then picked off the rubber until he had twenty small capsules which he put on a porcelain plate that he had taken from the kitchen cupboard.

‘There’s more milk. And there’s more pizza. You stay here. Eat, drink and throw up. We want the rest.’

The sitting room was warm, stuffy. The three men at the rectangular dark oak table were all sweating – too many clothes and too much adrenaline. He opened the door to the balcony and stood there for a moment while a cool breeze swept out all the bad air.

Piet Hoffmann spoke in Polish. The two men who had to understand what he was saying preferred it.

‘He’s still got eighteen hundred grams to go. Take care of it. And pay him when he’s done. Four per cent.’

They were very similar, in their forties, dark suits that were expensive but looked cheap, shaved heads; when he stood close to them he could see an obvious halo of day-old brown hair. Eyes that were devoid of joy and neither of them smiled very often. In fact, he’d never seen either of them laugh. They did what he said, disappeared into the kitchen to empty the mule who was lying there, throwing up. It was Hoffmann’s shipment and none of them wanted to explain to Warsaw that a delivery had gone tits up.

He turned to the third man at the table and spoke in Swedish for the first time. ‘Here are twenty capsules. Two hundred grams. That’s enough for you to check it.’

He was looking at someone who was tall, blond, in shape, and about the same age as himself, around thirty-five. Someone wearing black jeans, a white T-shirt and lots of silver round his fingers, wrists and neck. Someone who’d served four years at Tidaholm for attempted murder, and twenty-seven months in Mariefred for two counts of assault. Everything fitted. And yet there was something he couldn’t put his finger on, like the buyer was wearing a costume, or was acting and not doing it well enough.

Piet Hoffmann watched him as he pulled a razorblade from the pocket of his black denim jacket and cut one of the capsules down the middle then leant forward over the porcelain plate to smell the contents.

That feeling again. It was still there.

Maybe the guy sitting there, who was going to buy the lot, was just strung out. Or nervous. Or maybe that was precisely what had made Piet call Erik in the middle of the night, whatever it was that wasn’t right, this intense feeling that he hadn’t been able to express properly on the phone.

It smelt of flowers, tulips.

Hoffmann was sitting two chairs away but could still smell it clearly.

The buyer had chopped up the yellowish, hard mass into something that resembled powder, scooped some up on the razorblade and put it in an empty glass. He drew twenty millilitres of water into a syringe and then squirted it into the glass and onto the powder which dissolved into a clear but viscous fluid. He nodded, satisfied. It had dissolved quickly. It had turned into a clear fluid. It was amphetamine and it was as strong as the seller had promised.

‘Tidaholm. Four years. That’s right, isn’t it?’

It had all looked professional, but it still didn’t feel right.

Piet Hoffmann pulled the plate of capsules over in front of him, waiting for an answer.

‘Ninety-seven to two thousand. Only in for three. Got out early for good behaviour.’

‘Which section?’ Hoffmann studied the buyer’s face.

No twitching, no blinking, no other sign of nerves.

He spoke Swedish with a slight accent, maybe a neighbouring country. Piet guessed Danish, possibly Norwegian. The buyer stood up suddenly, an irritated hand slightly too close to Piet’s face. Everything still looked good, but it was too late. You noticed that sort of thing. He should have got pissed off much earlier, swiped that hand in front of his face right at the start: don’t you trust me, you bastard.

‘You’ve seen the judgement already, haven’t you?’

Now it was as if he was playing irritated.

‘I repeat, which section?’

‘C. Ninety-seven to ninety-nine.’

‘C. Where?’

He was already too late.

‘What the fuck are you getting at?’

‘Where?’

‘Just C, the sections don’t have numbers at Tidaholm.’

He smiled.

Piet Hoffmann smiled back.

‘Who else was there?’

‘That’ll fucking do, OK?’

The buyer was talking in a loud voice, so he would sound even more irritated, even more insulted.

Hoffmann could hear something else.

Something that sounded like uncertainty.

‘Do you want to get on with business or not? I was under the impression that you’d asked me here because you wanted to sell me something.’

‘Who else was there?’

‘Skåne. Mio. Josef Libanon. Virtanen. The Count. How many names do you want?’

‘Who else?’

The buyer was still standing up, and he took a step towards Hoffmann. ‘I’m going to stop this right now.’

He stood very close, the silver on his wrist and fingers flashing as he held his hand up in front of Piet Hoffmann’s face.

‘No more. That’s enough. It’s up to you whether we carry on with this or not.’

‘Josef Libanon was deported for life and then disappeared when he landed in Beirut three and a half months ago. Virtanen has been put away in a maximum security psychiatric unit for the past few years, unreachable and dribbling due to chronic psychosis. Mio is buried—’

The two men in expensive suits with shaved heads had heard the raised voices and opened the kitchen door.

Hoffmann waved his arm at them to indicate that they should stay put.

‘Mio is buried in a sandpit near Ålstäket in Värmdö, two holes in the back of his head.’

There were now three people speaking a foreign language in the room.

Piet Hoffmann caught the buyer looking around, looking for a way out.

‘Josef Libanon, Virtanen, Mio. I’ll carry on: Skåne, totally pickled. He won’t remember whether he did time in Tidaholm or Kumla, or even Hall for that matter. And as for the Count … the wardens in Härnösand remand cut him down from where he was hanging with one of the sheets round his neck. Your five names. You chose them well. As none of them can confirm that you did time there.’

One of the men in dark suits, the one called Mariusz, stepped forward with a gun in his hand, a black Polish-made Radom, which looked new as he held it to the buyer’s head. Piet Hoffmann utspokój się do diabla shouted at Mariusz; he shouted utspokój się do diabla several times, Mariusz had better utspokój się do diabla take it easy, no fucking guns to anyone’s temple.

Thumb on the decocking lever, Mariusz pulled it back, laughed and lowered the gun. Hoffmann carried on talking in Swedish.

‘Do you know who Frank Stein is?’

Hoffmann studied the buyer. His eyes should be irritated, insulted, even furious by now.

They were stressed and frightened and the silver-clad arm was trying to hide it.

‘You know that I do.’

‘Good. Who is he?’

‘C. Tidaholm. A sixth name. Satisfied?’

Piet Hoffmann picked his mobile phone up from the table.

‘Then maybe you’d like to speak to him? Since you did time together?’

He held the telephone out in front of him, photographed the eyes that were watching him and then dialled a number that he’d learnt by heart. They stared at each other in silence as he sent the picture and then dialled the number again.

The two men in suits, Mariusz and Jerzy, were agitated. Z drugiej strony. Mariusz was going to move, he should be on the other side, to the right of the buyer. Blizej głowy. He should get even closer, keep the gun up, hold it to his right temple.

‘I apologise. My friends from Warsaw are a bit edgy.’

Someone answered.

Piet Hoffmann spoke to whoever it was briefly, then showed the buyer the telephone display.

A picture of a man with long dark hair in a ponytail and a face that no longer looked as young as it was.

‘Here. Frank Stein.’

Hoffmann held his anxious eyes until he looked away.

‘And you … you still claim that you know each other?’

He closed the mobile phone and put it down on the table.

‘My two friends here don’t speak Swedish. So I’m saying this to you, and you alone.’

A quick glance over at the two men who had moved even closer and were still discussing which side they should stand on to aim the muzzle of the gun at the buyer’s head.

‘You and I have a problem. You’re not who you say you are. I’ll give you two minutes to explain to me who you actually are.’

‘I don’t understand what you’re talking about.’

‘Really? Don’t talk crap. It’s too late for that. Just tell me who the hell you are. And do it now. Because unlike my friends here, I think that bodies only cause problems and they’re no bloody good at paying up.’

They paused. Waiting for each other. Waiting for someone to speak louder than the monotonous smacking sound coming from the dry mouth of the man holding his Radom against the thin skin of the buyer’s temple.

‘You’ve worked hard to come up with a credible background and you know that it crumbled just now when you underestimated who you were dealing with. This organisation is built around officers from the Polish intelligence service and I can check out what the fuck I like about you. I could ask where you went to school, and you might answer what you’ve been told, but it would only take one phone call for me to find out whether it’s true. I could ask what your mother’s called, if your dog has been vaccinated, what colour your new coffee machine is. One single phone call and I’ll know if it’s true. I just did, made one phone call. And Frank Stein didn’t know you. You never did time together at Tidaholm, because you were never there. Your sentence was faked so you could come here and pretend to buy freshly produced amphetamine. So I repeat, who are you? Explain. And then maybe, just maybe, I can persuade these two not to shoot.’

Mariusz was holding the handgrip of the gun hard. The smacking noises were more and more frequent, louder. He hadn’t understood what Hoffmann and the buyer were saying, but he knew that something was about to go down. He screamed in Polish, ‘What the fuck are you talking about? Who the fuck is he?’ then cocked his gun.

‘OK.’

The buyer felt the wall of immediate aggression, tense and unpredictable.

‘I’m the police.’

Mariusz and Jerzy didn’t understand the language.

But a word like police doesn’t need to be translated.

They started shouting again, mainly Jerzy, he roared that Mariusz should bloody well pull the trigger, while Piet Hoffmann raised both his arms and moved a step closer.

‘Back off!’

‘He’s the police!’

‘I’m going to shoot!’

‘Not now!’

Piet Hoffmann lurched towards them, but he wouldn’t make it in time, and the man with the metal pressed against his head knew. He was shaking, his face contorted.

‘I’m a police officer, for fuck’s sake, get him off me!’

Jerzy lowered his voice and was bliźej almost calm when he instructed Mariusz to stand closer and to z drugiej strony swap sides again – it was better to shoot him through the other temple after all.

He was still lying in bed. It was one of those mornings when your body doesn’t want to wake up and the world feels a long way off.

Erik Wilson breathed in the humidity.

The south Georgia morning air that slipped in through the open window was still cool, but it would soon get warmer, even warmer than yesterday. He tried to follow the fan blades that played on the ceiling above his head, but gave up when he got tears in his eyes. He’d only slept for an hour at a time. They had talked together four times through the night and Paula had sounded more and more tense each time, a voice with an unfamiliar edge, stressed and desperate, on the verge of fleeing.

He had heard familiar sounds from the great FLETC training grounds for a while now, so it must be past seven o’clock, early afternoon in Sweden – they would be done soon.

He propped himself up, a pillow behind his back. From his bed he could look out through the window at the day that had long since dawned. The hard asphalt yard where the Secret Service had protected and saved a president yesterday was empty, but the silence after a pretend gunshot still reverberated. A few hundred metres away, in the next practice ground, a number of bright-eyed Border Patrol officers in military-like uniforms were running towards a white and green helicopter that had landed near them. Erik Wilson counted eight men clambering on board, who then disappeared into the sky.

He got out of bed and had a cold shower, which nearly helped. The night became clearer, his dialogue with fear.

I want you to get out.

You know that I can’t.

You risk ten to fourteen years.

If I don’t complete this, Erik, if I back out now, if I don’t give a damn good explanation … I risk more than that. My life.

In each conversation and in many different ways, Erik Wilson had tried to explain that the delivery and sale could not be completed without his backing. He got nowhere, not with a buyer and the seller and mules already in place in Stockholm.

It was too late to call it off.

He had time for a quick breakfast: blueberry pancakes, bacon, that light, white bread. A cup of coffee and the New York Times. He always sat at the same table in a quiet corner of the dining room as he preferred to keep the morning to himself.

He’d never had anyone like Paula before, someone who was as sharp, alert, cool; he was working with five people at the moment and Paula was better than all the others put together, too good to be a criminal.

Another cup of black coffee, then he had to rush back to the room: he was late.

Outside the open window, the green and white helicopter whirred high above the ground and three Border Patrol uniforms were hanging from a cable below, about a metre apart, as they shimmied down into pretend dangerous territory near the Mexican border. Yet another practice, always a practice here. Erik Wilson had been at the military base on the east coast of the USA for a week now; two weeks left of this training session for European policemen on informers, infiltration and witness protection programmes.

He closed the window as the cleaners didn’t like them being open – something about the new air conditioning in the officers’ accommodation, that it would stop working if everyone aired their rooms whenever they pleased. He changed his shirt, looking at the tall and fairish middle-aged man in th

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...