- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

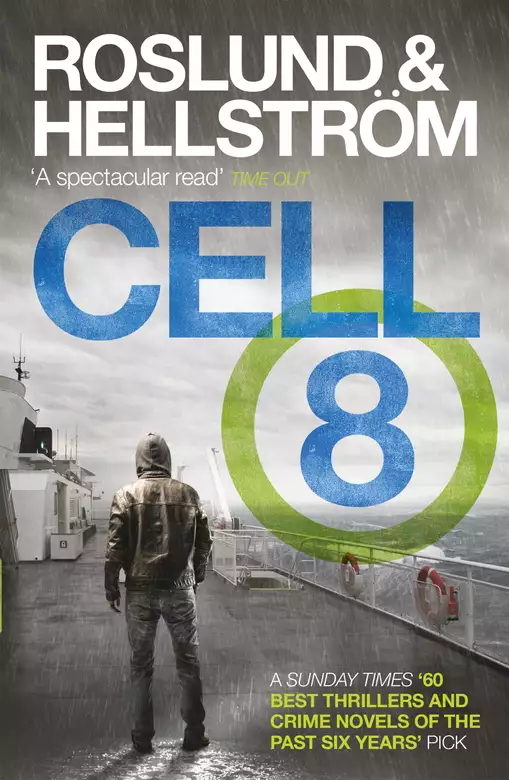

Synopsis

Convicted of brutally murdering his girlfriend, seventeen-year-old John Meyer Frey marks time in an Ohio maximum security prison, awaiting execution. For nearly a decade, the victim's father has hungered for Frey's death, while a prison guard is torn by compassion for the young man. When Frey unexpectedly dies of heart disease before he either receives his just punishment or achieves redemption, the wheels of justice grind to a halt.

Six years later, on a ferry between Finland and Sweden, a singer named John Schwarz viciously attacks a drunken lout, leaving the man in a coma. The Stockholm police arrest Schwarz and assign Detective Superintendent Ewert Grens to the seemingly straightforward assault case. But when Grens learns that the assailant has been living in Sweden under a false identity, he begins to suspect that something darker and more complex underlies the incident. Following his intuition, Grens launches an investigation that stretches from Sweden to the United States and reveals a shocking connection between the Frey and Schwarz cases.

Featuring a multilayered plot with a killer twist, Cell 8 takes you on a journey that explores the devastating repercussions of the death penalty as well as the fallout from the conflicting desires for public justice and private retribution.

Release date: September 15, 2011

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 480

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Cell 8

Anders Roslund

He knew that he would never get used to it.

His name was John Meyer Frey and the floor he was staring at was piss yellow and unnaturally shiny. The walls that assailed him had probably once been white and the ceiling over his head screamed of damp, the round stains on the greenish background making the fifty-five square feet seem even smaller than they actually were.

He took a deep breath.

Worst of all were the clocks.

He could cope with the endless corridor of countless iron bars that kept anything that wanted to escape locked in; he could put up with the sound of rattling keys that bounced off the walls so your head felt like it would burst and your thoughts were shredded. He could even put up with the shouting of the Colombian in Cell 14, which got louder and louder as the night wore on.

But not the clocks.

The corrections officers wore great bloody wristwatches in fake gold and it felt like the hands were taunting him whenever one of them passed his cell. At the far end of the corridor, on a water pipe that ran from the East Block through to the West Wing, was another one – he had never been able to fathom why, it seemed so out of place, hanging there, ticking away, unavoidable. Sometimes, he was certain of it, he also heard the church clock in Marcusville strike: the white stone church with the tall, thin steeple on the square that he knew so well. In the early morning in particular, when for a brief while it was almost silent and he lay still awake on his bunk, searching for something on the greenish ceiling, it pierced through the walls and counted the hour.

That’s what they did. Counted. Counted down.

Hour by hour, minute by minute, second by second, and he hated knowing how much time was no longer left – that two hours ago his life had been longer.

It was one of those mornings.

He had lain awake nearly all night, twisting and turning and trying to sleep, sweating and feeling those minutes. The Colombian had shouted more than usual; he’d started around midnight and carried on through the night until sometime after four, his fear ricocheting off the walls in the same way that the rattling keys did, his voice getting louder and louder by the hour, something in Spanish that John couldn’t understand, the same thing, over and over again.

He’d dozed off around five, didn’t look at a clock, just knew that it was around then; it was as if time was inside him, his body counting down even when he did everything he could to think about something else.

Half six, no later. He woke up.

The smell of the cell assaulted him; the first breath made him gag and he hung over the dirty toilet bowl. It was more like a porcelain hole with no lid that was far too low even for someone who was one metre seventy-five. He had gone down on his knees, waiting to spew, and then had to put his fingers down his throat when it didn’t happen.

He had to empty himself.

Had to get rid of that first breath, had to get it out; difficult to get up otherwise, difficult to stand up.

He hadn’t slept through a whole night since he came here, four years ago now, and he had stopped hoping that he ever would. But last night, this morning, had stolen more from him than any other morning or night.

It had been Marvin Williams’s second-to-last night.

About lunchtime, the old man would be escorted down the secure corridor, over to the Death House and into one of the two cells there.

His last twenty-four hours.

Marv, who was his neighbour and friend. Marv, who had been on Death Row the longest now. Marv, so wise, so proud, so different from the other madmen.

Diazepam enema up the anus. Marv would be dribbling by the time they came to get him, he would be drugged and docile towards the end. He would slowly and drowsily allow himself to be escorted out by the men in uniform and by the time they locked the door of East Block, he would have forgotten the smell.

‘John?’

‘Yes?’

‘You awake?’

Marv hadn’t slept either. John had heard him tossing and turning, walking round and round his tiny cell, singing something that sounded like children’s songs.

‘Yes, I’m awake.’

‘I didn’t dare shut my eyes. D’you understand, John?’

‘Marv …’

‘Scared of falling asleep. Scared of sleeping.’

‘Marv …’

‘You don’t need to say anything.’

The bars were off-white, sixteen ugly iron bars from one wall to the next. When John stood up and leaned forwards, he did what he always did – he put his thumb and index finger round one of the bars, encircling the metal, holding on. Always the same, one hand, two digits, he enclosed what enclosed him.

Marv’s voice again, one of those deep baritones, calm.

‘It’s just as well.’

John waited in silence. They had spoken to each other ever since he came here. On the very first morning, Marv’s friendly voice had helped him to get up, to be able to stand up without losing his balance. The conversation had carried on ever since, and was still going on; staring straight ahead through the bars at the wall opposite, for several years, without being able to see each other. But now. His voice caught in his throat. He coughed. What do you say to someone who is only going to live for a day and a night more, then die?

Marv was breathing heavily.

‘You know, John, I can’t stand waiting any longer.’

_______

They read quite a bit. John had never read before. Not through choice. After a few months, Marv had forced Huckleberry Finn on him. A bloody children’s book. But he’d read it. Then another one. Now he read every day. So he didn’t have to think.

‘What will it be today, John?’

‘Today, I want to talk to you.’

‘You have to read. You know that.’

‘Not today. Tomorrow. I’ll read again tomorrow.’

_______

Marv. The only black man in town.

That was how he used to introduce himself. That was what he’d said that first morning when John’s legs didn’t want to work. A voice from the other side of the cell wall, and John had reacted in the way he always reacted: he told the voice to go to hell and eat shit. The only black man in town? John had seen for himself when the four guards had escorted him down the corridor and opened the door and then locked it for the first time. Not many other white men in East Block. He was on his own. Seventeen years old, and more terrified than he’d ever been in his life. He’d spat at the wall and kicked it until small chips of plaster powdered his shoes and he had shouted bloody nigger, I’ll get you until his voice was hoarse.

And so it continued in the evening. ‘Hi, my name’s Marv, the only black man in town.’ John didn’t have the energy to shout any more. And Marv had just carried on, told him about his childhood in some hole in Louisiana, how he had moved to a mining town in Colorado, that he’d visited a beautiful woman in Columbus, Ohio, when he was forty-four and gone into the wrong Chinese restaurant at the wrong time and seen two men die at his feet.

‘Are you frightened?’

Death. The one thing they couldn’t think about. The only thing they thought about.

‘I don’t know, John. I don’t know any more.’

_______

They’d talked without stopping all morning, so much to say when time would soon cease to be.

They’d watched others being escorted out; they knew the procedures that were written down in the Department of Rehabilitation and Correction’s manuals and that hung on the walls round about, telling you how you would live, hour by hour, in your last twenty-four. A female doctor had been in earlier, put diazepam in a tube up his anus and Marv was slowing down now as a result. He slurred as he tried to keep control of his words and it sounded like he was dribbling out of the corner of his mouth when he spoke.

John wished he could see him.

All this, to be standing beside someone and yet not, to be close to someone and yet not be able to touch him, not even put a hand on his shoulder.

The door at the end of the corridor opened.

Hard heels clacked on the piss yellow.

The peaked hats, like caps, the green-brown uniforms, the shiny black boots; four guards marching, two by two, down to Marv’s cell. John followed every step, saw them stop a couple of yards away, their faces turned to what was on the other side of the wall.

‘Put out your hands!’

Vernon Eriksen’s voice was quite high, his dialect typical of south Ohio, a local boy who’d come to work at the prison in Marcusville for a summer when he was nineteen and had stayed, and was then promoted to senior corrections officer on Death Row only a few years later.

John couldn’t see what was happening any more, the big uniforms were in the way.

But he knew.

Marv’s hands were poking through the bars and Eriksen had put the handcuffs round his wrists.

‘Open Cell Seven!’

Vernon Eriksen, a corrections officer whom John had slowly come to respect. The only one. The only one who got involved in the inmates’ daily life, despite the fact that he didn’t really need to or in fact shouldn’t at all.

‘Cell Seven open!’

The central security PA system crackled, the door to Marv’s cell slid open. Vernon Eriksen waited, nodded to his colleagues and stayed standing where he was while two officers entered the cell. John watched him. He knew that the senior officer hated doing this. Collecting a prisoner that he’d come to know, escorting him to the Death House, preparing him for death. It was not something he’d ever said, it was not something he could ever say, but John had understood and recognised it a long time ago, he just knew. He was tall, Eriksen, not muscular but solid, with thinning hair, an old-fashioned pudding-bowl haircut like an inverted grey halo under the rim of his uniform hat. He was looking into Marv’s cell, watching the movements of his colleagues, his white gloves fiddling with the two sets of keys that hung from his belt.

‘Stand up, Williams.’

‘It’s time, Williams.’

‘I know that you can hear me, Williams, stand up, for God’s sake, so I don’t need to lift you.’

John heard the two officers forcing his neighbour up from the bunk, feeble protests from a drugged sixty-five-year-old man. He looked at Vernon Eriksen again, who was still facing the cell. He wanted to scream, but not at the senior officer, who bizarrely was on their side, so to shout at him would be meaningless. Instead he turned around and pissed into the hole that was supposed to be a toilet. No words any more, no thoughts. As Marv was led out of his cell on the other side of the wall, John chased a piece of paper down into the water-filled hole. He forced the piece of paper back and forth with his jet stream until it finally stuck to the white porcelain.

‘John.’

Marv’s voice, somewhere behind him. He buttoned up his overalls, turned around.

‘I want to talk to you, John.’

John looked at the senior officer who gave a curt nod, then approached the bars, the metal bars between the lock and the concrete walls. He leaned forwards, as he always did, his thumb and index finger encircling one of the bars. Suddenly, he was face to face with a person he had seldom seen, but had spoken to several times a day, for the past four years.

‘Hi.’

That voice that he knew so well, friendly, safe. A proud man, straight-backed, his black hair had long since turned grey, clean shaven as John had always imagined he would be.

‘Hi.’

Marv was dribbling. John could see that he was trying to concentrate, that the muscles in his face would not obey. A prisoner who is about to die has to be sedated, no unnecessary anxiety; John was certain it was in fact for the officers’ sake, to quell their fear.

‘This, this is yours.’

John watched Marv lift his hand to his neck, how he fumbled for a while with deadened fingers, but finally got hold of what he was after.

‘I would have to take it off later anyway.’

A cross. It meant bugger all to John. But everything to Marv. John knew that. Marv had found God a couple of years ago, like so many others who were kept in this corridor while they waited.

‘No.’

The older man bundled up the silver chain, wrapped it round the crucifix and thrust it into John’s hand.

‘There’s no one else. To give it to.’

_______

John looked at the chain he was now holding and then uneasily over at Vernon Eriksen again.

The senior corrections officer’s face – John had never seen it like this before.

It was completely red. Like he was in spasm, like it was burning. And his voice, it was too forceful, too loud.

‘Open Cell Eight!’

John’s cell.

That wasn’t right. John looked at Marv who didn’t seem to react, then at the three other officers who stood still, but glanced at each other, confused.

The cell door was still locked.

‘Please repeat, sir.’

A voice from central security over the PA system.

Vernon Eriksen lifted his chin in irritation, made sure he was looking straight at the officer at the other end of the corridor when he spoke: ‘I said, open Cell Eight. Now!’

Eriksen stared at the bars, waiting for the door to slide open.

‘Sir—’

One of the three officers appealed to him by throwing open his hands, but he had barely opened his mouth before his boss interrupted.

‘I am aware that I am now deviating from the set time schedule. If you have a problem with it, please file your complaint in writing. Later.’

He looked over at central security again. A few more seconds of uncertainty.

They all stood in silence as the cell door slowly slid open.

Vernon Eriksen waited until it was fully open, then turned to Marv and nodded in the direction of the cell. ‘You can go in.’

Marv didn’t move. ‘You want me to … ?’

‘Go in and say goodbye.’

_______

It got cold later, damp, there was a draught from the window in the corridor high up by the ceiling, a muted whistle that dropped to the floor. John buttoned his overalls right up to the collar, orange cotton with no fit, and the letters DR printed in white on the back and thigh.

He was shivering.

Maybe it was the cold.

Or maybe it was the grief that he was already starting to fight.

HE STRUGGLED AGAINST the strong wind. No one else on deck. They were all inside, somewhere in the floating community of restaurants and dance floors and duty-free shops. He heard someone laugh, then the murmur of voices and the clinking of glasses, music pumping electronically from one of the lounges full of beautiful young things.

His name was John Schwarz and he was thinking of her. As he always did.

The first person he had really been close to. The first woman he’d ever touched; her skin, he could feel it, dream it, yearn for it.

It was eighteen years now since she died.

To the day.

He moved towards the door, one last deep breath of cold Baltic air, then into the boat that smelt of engine oil and drunkenness and cheap perfume.

Five minutes later, he was standing on a tiny stage in a huge lounge, looking out over the crowd who would be his audience for the evening, who were there to be entertained between drinks and cocktail umbrellas and bowls of peanuts.

Two couples. In the middle of the dance floor, which was otherwise empty.

He cocked his head. He wouldn’t have spent his Thursday night on the Åbo ferry either if he could help it. But the money – with Oscar at home, he needed it more than ever.

Three quick numbers with a swinging four-beat usually woke them up and there were already more people on the floor; eight couples holding each other tight, leaning in towards one another, hoping that the next number would be the first slow dance, one that required body contact. John sang and searched among the dancing people and those standing round the edge of the floor waiting to be asked. There was a woman, so beautiful, with long dark hair, dressed in black, who bubbled with laughter when her partner stepped on her toes. John followed her with his eyes and thought of Elizabeth who was dead and of Helena who was waiting for him in a flat in Nacka; this woman, both of them – Helena’s body and Elizabeth’s movements. He wondered what she was called.

They’d had a break and a drink of mineral water. His shirt, which was turquoise and blue with a black collar, was now soft and damp under the arms from the smoke and spotlights that harassed him. He was still trying to make eye contact with the woman, who had not left the floor for a moment, she had just switched partners a couple of times, and was hot now too, her face and neck glistening.

He looked at his watch. One more hour.

One of the passengers, whom he recognised from a couple of trips around Christmas, approached the throng on the dance floor. He was the sort who got drunk and was calculating, accidently touching women’s thighs whenever he could. He moved between the couples and had already brushed a young woman’s breasts for a moment. John wasn’t sure whether she’d noticed, they seldom did; what with the music and the passing bodies, a groping hand just vanished.

John hated him.

He’d seen men like him before: they were drawn to the band, dance music and strong beer and sprayed their angst on anyone who got in the way. A woman who danced and laughed was also a woman who, in the dark, you could press against, grope, steal from.

And then he took something from her.

The one who was Elizabeth and Helena.

The one who was John’s woman.

The man slid his hand on to her behind as she turned away; he came too close and ended up thrusting his crotch against her hip in what appeared to be a clumsy dance step. She was like all the others, enjoying herself too much and too nice to realise that he had just stolen something from her. John sang and he watched and he trembled, felt the anger that had once fired him up and made him fight. For a long time he had hit people, now he just hit walls and furniture. But this creep, this man who took what he could, he had rubbed against one woman too many.

HE LAY DOWN on the bunk and tried to read. It didn’t work. The words just swam on the page, thoughts that wouldn’t focus. It was just like it had been when he first came here, when he was new, and after a fortnight of kicking the walls and iron bars he’d realised that it was simply a matter of putting up with it, that he had to keep breathing while his appeals filled space, to find a way to pass the time without counting.

But today, today was different. Today he wasn’t doing it for his own sake. He knew that. He was thinking of Marv. It was Marv he was reading for. John, every morning the same question, what’s it going to be today? It was important to Marv. Steinbeck? Dostoevsky?

Four uniformed officers had just escorted the sixty-five-year-old man down the long corridor of locked cells. He was dribbling, thanks to the sedatives they’d given him, and his legs had buckled under him several times, but he’d kept his composure; he hadn’t screamed or cried, and the sharp barbed wire above their heads had twinkled dismally in the weak light that managed to force its way in through the small windows even further up by the ceiling.

For John Meyer Frey, Marvin Williams was the closest to what other people called a true friend that he’d ever had. An elderly man who had eventually cajoled the aggressive and terrified seventeen-year-old boy into talking, thinking, longing. Perhaps that was what the senior officer had seen – a sense of family strong enough to make him grossly neglect security procedures. They had stood face to face in John’s cell, talked quietly together, feeling Vernon Eriksen watching them from the corridor, allowing a few minutes of shared time.

Now he was going to die.

His choice, electric chair or lethal injection. Marv had never been like the others. He hadn’t made the same choice as the others.

He was in the Death House, in one of the two death cells in Marcusville – the final destination for your last twenty-four hours of life, cell number four or cell number five. No other cell had the same number, the number of death, not here, not in East Block, not anywhere else in the great prison. One, two, three, six, seven, eight. That’s how they counted in all the units, all the corridors.

The only black man in town.

He had explained after a few months of nagging, once John started to read the books he recommended. Before the Chinese restaurant with the two dead men at his feet in Ohio, Marv had lived in the mountains of Colorado, in Telluride, an old mining community that had been deserted when the minerals were exhausted. It died out for a while until hippies from the city had moved there in the sixties and transformed it to suit their alternative lifestyle. A couple of hundred enlightened, young, white Americans who believed in what you believed in then: freedom, equality, brotherhood and everyone’s right to roll a joint.

Two hundred white people and one black man.

Marv really had been the only black man in town.

And some years later, whether it was to provoke people or to demonstrate brotherhood and all that, or due to his constant need for money, he had agreed to marry a woman from South Africa who needed a green card. He had regularly appeared in front of a panel of officials and explained that the only true love for the town’s only black man was, of course, this white woman from the home of apartheid, and he had done this so successfully that she was an American citizen by the time they got divorced some years later.

It was also for her sake that he’d gone to Ohio and stepped into the wrong restaurant.

John sighed, gripped the book even harder, tried again.

Throughout the afternoon and evening, he managed to read only a few lines at a time. He kept picturing Marv in the death cell, which had no bunk – maybe he was sitting there now, on the blue stool that stood in the corner, or he was lying curled up on the floor, staring at the ceiling.

A few more lines, sometimes a whole page, then back to Marv.

The light slowly drained from the small windows and was swallowed by the night. It was hard to lie next to the empty cell and not listen out for Marv’s heavy breathing. To his surprise, John managed to sleep for a couple of hours. The Colombian made less noise than usual and he was tired from the night before. John woke around seven, with the book under him, then lay there for a few hours more, before rolling over and getting up, almost refreshed.

He could hear clearly that they were visitors.

It was easy to differentiate between the voices of people who were free and those who had been sentenced to death. It was easy to recognise the tone that you only hear in the voice of someone who doesn’t know precisely when they’re going to die, the uncertainty that allows them not to count.

John looked down towards central security. He counted fifteen people as they passed.

They were early – still three hours to go until the execution – and they filed slowly past, peering down the corridor with curious eyes. At the front, the prison warden, a man whom John had only seen once before. The witnesses followed after him. John assumed that it was the usual: a few members of the victim’s family, a friend of the person to be executed, some representatives of the press. They were all wearing overcoats and the snow still lay on their shoulders; their cheeks were red, due to the cold or in anticipation of watching someone die.

He spat in their direction through the bars. He was just about to turn round when he suddenly heard central security opening the door and letting someone into the corridor of East Block.

It was a short, stocky man with a moustache and dark, slicked-back hair. He was wearing a fur coat over his grey suit; the snow had melted and the fur was wet. He marched down the middle of the corridor, his black rubber moccasins slapping on the stone floor, even though they looked soft. There was no hesitation, he knew where he was going, to which cell he was headed.

John brushed his hair down with a nervous hand and tucked it behind his ears, as he always did, his pigtail hanging down his back. He’d had short hair when he came here but had let it grow ever since, every month another half inch, in case he ever lost the clock that ticked inside him.

He could see the visitor clearly now, as he had stopped squarely in front of his cell; the face that he fled from in the dreams that perpetually haunted him, a face that had once been full of acne and now carried the scars that time and good-living had not erased. Edward Finnigan was standing outside in the corridor, his colour leeched by winter, his eyes tired.

‘Murderer.’

His lips were tight. He swallowed, raised his voice.

‘Murderer!’

A fleeting glance over his shoulder to central security; he realised that he should keep his voice down if he wanted to stay.

‘You took my daughter from me.’

‘Finnigan …’

‘Seven months, one week, four days and three hours. Exactly. You can appeal as much as you like. I’ll make sure that your appeals are turned down. In exactly the same way that I’m able to stand in front of you now. You know it, Frey.’

‘Go away.’

The man who was trying unsuccessfully to talk quietly raised his hand to his mouth, a finger to his lips.

‘Shhh, don’t interrupt. I don’t like it when murderers interrupt me.’

He moved his finger away. The forcefulness returned to his voice, a force that only hate can provoke.

‘Today, Frey, I’m going to watch Williams die, courtesy of the governor. And in October, I’ll be watching you. Do you understand? You only have one spring, only one summer left.’

The man in the fur coat and rubber moccasins was finding it hard to stand still. He hopped from one foot to the other, moved his arms in circles; the hate that he had stored in his belly was being released into his body, forcing his joints and muscles to jump forwards. John stood silent, as he had when they met during the trial. The words were to much the same effect; at first he had tried to answer, but had then given up. The man in front of him didn’t want any answers, any explanations; he wasn’t ready for that, never would be.

‘Go away. You’ve nothing to say to me.’

Edward Finnigan dug his hand into one of his coat pockets and took out something that looked like a book – red cover, gold-edged pages.

‘You listen to this, Frey.’

He leafed through the pages for a few seconds, looking for a bookmark, found it.

‘Exodus, Chapter Twenty-One …’

‘Leave me alone, Finnigan.’

‘… twenty-third, twenty-fourth and twenty-fifth verses.’

He looked over towards central security again, tensed his jaw, gripped the Bible with white fingers.

‘But if there is serious injury, you are to take life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth…’

Edward Finnigan read the text as if it were a sermon.

‘… hand for hand, foot for foot, burn for burn, wound for wound, bruise for bruise.’

He smiled as he slammed shut the book. John turned around, lay down with his back to the bars and corridor, fixed his gaze on the dirty wall. He lay like this until the steps receded down the corridor and the door at the end was opened and then closed again.

_______

Fifteen minutes to go.

John didn’t need a clock.

He always knew exactly how long he’d been lying down.

He looked at the fluorescent tube on the ceiling, the glass covered with small black marks. Flies that had been attracted to the light . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...