- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

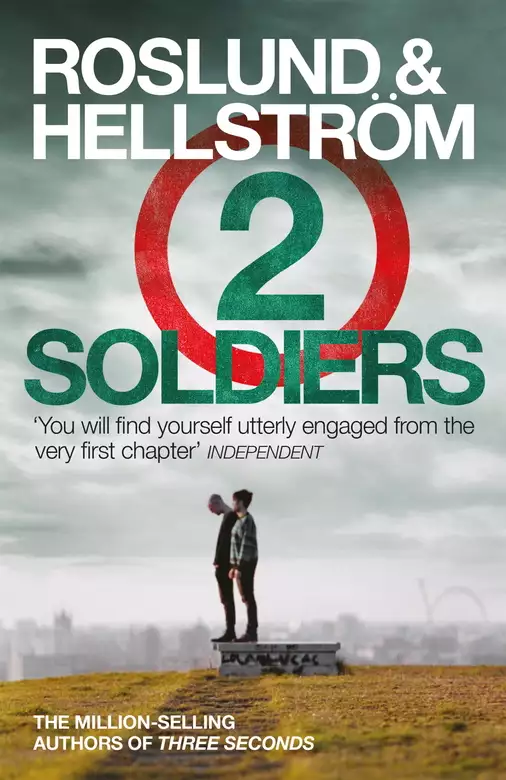

THE MILLION-SELLING AND CWA AWARD-WINNING DCI EWERT GRENS SERIES CONTINUES, AS ROSLUND AND HELLSTRÖM SHIFT THEIR SOCIAL SPOTLIGHT TO SWEDEN'S NETWORK OF CHILD GANGS. 'You will find yourself utterly engaged from the very first chapter' Independent 'Very bold and very scary . . . a book to appreciate ' Crime Thriller Fella TWO SIDES. In the Stockholm suburb of Råby, tensions between the Swedish authorities and organised juvenile gangs are approaching critical mass. TWO SENTINELS. Investigators José Pereira and DCI Ewert Grens are increasingly disturbed by the escalating militancy of these criminal enterprises. TWO SOLDIERS. The police are of little concern to blood brothers Leon and Gabriel. They have vowed to secure dominance in the area, at any cost. A dangerous collision awaits both sides. And so does a shocking revelation that will make all four men question the direction their lives have taken. Loved Two Soldiers and now want to start the DCI Ewert Grens series from the beginning? Take a look at Pen 33 . . .

Release date: April 25, 2013

Publisher: RiverRun

Print pages: 584

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Two Soldiers

Anders Roslund

It’s mostly voices.

Maybe footsteps.

When they pass outside in the long corridor, the fast ones and ones that seem to shuffle along; sometimes they stop by the metal door, as if they’re listening, and she wants to call out to them, ask them to come in and hold her hand. They never do. They carry on down the corridor, steps that drown in the regular beep of the machine and the ticking of the bright lights – beep tick beep tick – she closes her eyes but doesn’t dare to cover her ears – beep tick beep tick – she’s on her own and doesn’t want to be.

Her face, so strange.

She’s sixteen, maybe seventeen, or even eighteen.

But she looks old. Whether it’s the pain, fear, or whatever, how the body encapsulates time, lets it settle.

She seems to be lying comfortably, the stretcher she’s been rolled onto is wide and her body is thin. The room is much bigger than the others, the bed and cupboard and table and chair and shower and it’s – even though someone is breathing close by – almost empty. The green overall by her feet, a hand rubbing up and down on the coarse material to warm it up before moving to her young thighs, carefully touching her genitals, fingertips against the head of her uterus, while the other hand keeps a firm hold of the needle, thirty centimetres of plastic tubing against the membrane that is so soft, a clear balloon of water flying, bouncing away. The needle again, again, again, it gives up, breaks.

Footsteps that stop and then vanish.

Someone opens a door further up. Someone else screams, or cries, it’s hard to make out.

She doesn’t have her eyes closed any more. It’s white, everything she sees, white, almost glossy, the naked lights and the machine with its digits and green lines and thin tubes. It’ll take a while, and then a bit more, before her eyes get used to it.

It doesn’t hurt as much anyway. Or she’s just coping with it. Like her period. Exactly the same. But more, more often, longer.

Two of the people in the room, both women, are wearing green overalls. The others, three women and three men, are wearing white overalls that cover dark trousers, dark shoes.

The green ones are standing nearest, the white ones further away, nearly by the wall.

She doesn’t know any of them, at least she doesn’t think she does, or maybe, that woman, she recognises her, she works here, and him, the one who broke down the door and screamed at her, held her to the floor, put her in an armlock.

It’s easier to see now. She turns towards the window. It’s dark outside, cold, the snow is deep; only a few days ago she made an angel out there, lay down on the ground and swept her arms and legs back and forth, back and forth until they shouted at her, came over and grabbed her hands and carried her in. Now there’s an ambulance out there beside her angel, in the middle of the big yard. She tries to get up so she can go over to the window and wave down at the guard who’s waiting by the front of the car, a thick cloud where his breath meets the cold air.

‘Come on.’

The green overall sighs; the thin body on the stretcher looks so vulnerable, so wrong.

‘Come on, you have to lie down.’

Sweetie. Not here.

The room the corridor the metal door the bars.

Sweet, sweet, sweetie.

‘Did you hear me? You have to lie down.’

The green overall’s hands on her arms, chest, thighs, they pull at the hard, brown strap down her back, point the electronic arm at exactly the spot on her stomach where the heartbeat can be heard loudest, one hundred and forty-seven beats per minute, racing, speeding.

She’s almost completely dilated now, nine centimetres, not long now.

Like waves. Like fire.

Something hitting, pressing, forcing. It’s happening inside her body. But she has no control.

She tries to look over at the window again, the bars that are in the way, the round black steel poles across the great sheet of glass. Out there – inside the fence and sharp barbed wire – the searchlights brush the white snow, such a different light compared to ordinary street lamps. The ambulance is still there by the snow angel and the guard is slapping his arms to his sides to keep warm, and if she raises her head a bit more and lets go of the rough edge of the bed, she can see the other car as well, small, grey and completely dark.

‘The waters?’

‘Clear.’

‘Head?’

‘Engaged.’

The people in green overalls are constantly touching her, talking to her. The people in white overalls are standing still with their backs to the wall.

She’s lying here for security reasons.

That’s what they said.

A risk that she might try to escape.

The waves. The fire. The pressure. The pounding. The force.

She screams.

The ribcage that is squeezed together as it passes through the birth canal and the water that is forced out and the lungs that are filled with air – the first breath.

It’s not her. She realises now. It’s not her who’s screaming.

Something wet, warm on her stomach. A baby. Her baby. She sees it as the two hands that quickly become four hands lift it up, carry it across the room, through the door, out into the corridor, away.

The woman and the man – the ones holding the baby, who went away with it and then came back without it – are taking off their white coats now, jeans and a jacket underneath, and the woman reaches over for a briefcase, fills in one sheet of paper, then another and another. The others – who’ve been standing farthest away, almost blocking the door, who haven’t spoken at all – are wearing blue under the white. The course material of the prison service uniform, oblong name tags in hard plastic just over their left breast. The men beside them have normal suits on underneath, they’re not wearing uniforms, but she still knows that they’re police; the big one in his forties is a detective inspector and the other one’s a police trainee and not much older than her.

She doesn’t know them, and yet they’ve seen her naked, being emptied.

It had been lying on her stomach, breathing close, a wet mouth.

They should have put a blanket over the red and white skin that was soft and smooth and that no one had touched.

She looks out of the barred window again. The midwife and the nurse open the doors to the white ambulance, a mobile incubator held like a basket between them. The grey private car immediately behind, the couple in jeans and jackets open the front doors and get in, the vehicles drive in convoy down the asphalt strip across the yard to the high fence and sharp barbed wire, the gate slowly slides open, then one carries on towards the hospital in Örebro, whereas the other has farther to go, to the family unit in Botkyrka.

She wonders whether the shiny road is slippery, if it’s difficult to drive so far at night.

She’s not said anything for a while now.

Not when they took the baby that was resting on her tummy, not when the two vehicles left Sweden’s top security prison for women.

And it’s as if she can’t bear it any more, the silence.

She turns towards the only person still in the room, the one that’s a policeman in his forties, who held her to the floor, forced her out of her home.

‘Did you see?’

He starts, lost in his own thoughts, or maybe he’s just forgotten what her voice sounds like.

‘See what?’

She points to her tummy, which is still wet, she should maybe wipe away the clear stuff and the other stuff that’s a bit bloody.

‘If it was a boy or a girl?’

LIGHT OUTSIDE.

The blanket that was red with a touch of yellow and perhaps a thin white stripe round the edge, didn’t cover the whole of the dirty window.

He could see that now.

They normally lived in the dark and slept through the light, only waking when the evening and night had returned, but in August – and with that bloody blanket that wasn’t as big as it should be – the day ambushed them around about this time; no matter how tightly he shut his eyes, the transparent square on the inside of his eyelids got bigger, it grew and wormed its way slowly in, into his brain, into his chest.

He punched the wall and sat up in the low bed, a thick mattress that had been in one of the big houses at Hägersten, the sort that costs about twenty thousand, a thick square on the shiny linoleum floor.

She was naked, asleep.

Her pale, soft skin; she was lying so still, her back towards him and he carefully ran his hand down her hip, behind, thigh, she moved uneasily, turned over, maybe she was dreaming – it looked like it – her face tense and rubbing her feet together, as she often did.

He was just as naked. He sometimes forgot. How incredible that was. Another person who could see his skin and didn’t laugh. Sometimes he wondered if it was all in his head. He had been so fucking certain that he knew what they saw. He wasn’t any more. It had started with Leon, they were eleven and one day they had ended up in the same room, watching each other take their clothes off and his eyes – no repulsion, scorn, or even surprise. Until now, only Leon, no one else. Not even the mirrors. He had smashed all the ones at his mum’s and turned away every time he went past the wide, rectangular one at his gran’s, every time he went down the hall, he knew exactly when it was looking at him and exactly when to look away.

He looked at her.

Never a woman. Not before her. She hadn’t said anything either, hadn’t been frightened, or evasive, or even asked questions.

His hand was still on her hip, she opened her eyes, squinted at him, with small pupils that focused on the light shining in through the gap between the blanket and the window frame. Her gentle fingertips on his back, over the skin that was thick with uneven edges, pieces of a jigsaw puzzle lying in a heap instead of laid out flat, he had lain on top of her for a long time after, she had her period and they both smelled pretty potent. It was hard to lie there without moving, sweat slipping on sweat.

He wasn’t tired. He should be. Early morning and they never usually got up before late afternoon; if he was to guess, they’d been asleep for about three hours, couldn’t be helped sometimes.

He dried himself with the sheet, then smoothed on the cream from the white tube that was always close to the bed, his feet legs balls back stomach neck, but never his face, never there.

‘Give it to me.’

He looked at her.

‘What?’

‘Gabriel, give it to me. The tube. I’ll rub it in, you can’t reach everywhere properly, like on your shoulders, your back.’

She held out her hand for the sticky, broken tube and he rapped her hard, the palm of his hand against her fingers, a red mark across some of them. He stared at her and she looked down; he turned away and rubbed cream onto his chest and thighs.

They left the bedroom, out into the sitting room; fully clothed bodies in the corner sofa and armchair and further away on the floor – Jon, Big Ali, Javad Hangaround, Bruno – stoned, sleeping, breathing.

He nudged, shook …’

He slapped Javad in the face.

She shouldn’t have reached for the cream.

‘You gotta wake up, brother.’

‘Why?’

She shouldn’t have asked to put cream on his back.

‘Because I’m awake.’

Fags ends, bottles, needles, cans on the table top that was covered in yellowish swill, spat-out peanuts and leftover pizza salad. They were awake now, but just lying there, exhausted as you are after only a couple of hours’ sleep, and he leaned over towards the new TV screen, searching for the purring high pitch that had accompanied the night and still reverberated in the walls of the room. They all stirred when he turned it off, even the stack of DVDs wobbled, fell forwards.

The hallway had always been empty.

No furniture, no rugs, no lamps.

Only one thing leaning up against the wall, long and shiny with rows of tiny, tiny white pearls around the edge. He really liked it, often straightened it – it was important that it could be seen when he and she came in the front door. A shoehorn. From when they’d burgled that enormous fucking pile outside Södertälje. They’d sold the rest to that guy in Nacka, but the shoehorn, he didn’t sell it.

She was still naked.

He kissed her tits and handed her her jeans and a cropped T-shirt with shiny writing on it; his own clothes were still on the chair out on the balcony, the black joggers with white stripes, grey hoodie, red baseball cap.

He was hungry. He wasn’t usually hungry in the morning.

The top shelf in the fridge – what was left of a big bottle of Coke.

On a narrow shelf in the larder, an unopened packet of wine gums, he picked out the red and green ones.

It was blowing a bit outside, easy to breathe.

They walked side by side, he thought she was beautiful, he knew that he wasn’t. They passed the first parking place and she headed towards a silver BMW, eight hundred and fifty thousand in cash, but he caught her hand, not that one, not today. They walked slowly through his past, present and future. He knew every concrete block, every asphalt path, listened to what no one else could hear, could distinguish the smells, the one from a burnt-out rubbish room and the one from the deserted kiosk where he’d bought sweets, porn, hash when he was a kid, even the smell that wasn’t there any more, the sweet smell that came from the fruit stall on the square, the bastards should have paid more.

The whole of Råby was empty.

The concrete tower blocks so silent, desolate, not even the curtains in the windows twitched. He turned to Wanda, her face and eyes, and he wondered what she really saw, she who hadn’t seen what others saw, who came from another world further away, this was the Råby she could see, no other images, not like the ones from before, when there were more people outside.

The metro, like a living, reliable blue vein running through something that didn’t exist.

The image, maybe the smell he liked best.

The way in. The way out.

The steps down; they walked past a skinny little guy, might have been ten but was actually twelve, gold chain round his neck, hair greased back.

‘Gabriel.’

The runt had said his name. He didn’t turn round.

‘Gabriel!’

He stopped. Four fast steps back.

The little guy smiled proudly and held out his hand.

‘Sho, bro.’

Ran his other hand through his slickback, stood a little taller.

A hard slap.

The one cheek.

An obvious mark left by one of his rings.

‘You know …’

Gabriel looked at the runt. Not a flicker. Just as proud, just as tall. His voice just as jarring when he held out his skinny hand again, didn’t give in.

‘… Eddie’s the name. One love, brother.’

Gabriel didn’t hit him again.

He carried on down the stairs and past the old tart in the ticket office and she said nothing, not even when he turned round and nodded at Wanda, she was with him and she wasn’t going to pay and no one was going to make a fuss.

They leaned against the window, the glass cold against their foreheads, past stations that all looked the same.

The same concrete blocks, the same people on their way home, on their way out.

Hallunda, Alby, Fittja, Vårby gård, Vårberg, Skärholmen. Twelve and a half minutes.

They got off, went through a shopping centre that with every revamp got more like a gallery and less of a hub, the shiny glass walls of the elevator, down to three thousand parking spaces. They went as far back as they could – new signs and new colours, but it smelt the same, damp and exhaust.

He asked for the Adidas bag and picked out a Mercedes. A slightly older model. They were the easiest.

He started the clock on his mobile phone and 00.00 lay down on his back on the mucky asphalt and with bent legs pushed his torso back under the car, arms above his head 00.05 in the small space behind the grille, looking for the red cable that was thin and obvious and attached to the car alarm. As was his habit, he used a small pair of hairdresser’s scissors to cut through the red plastic, then wriggled back out and stood up, the newly sharpened end of a screwdriver into the petrol tank lock 00.11, then a wrench round the screwdriver handle, he turned, could almost hear the air pressure drop, and all the doors opened simultaneously.

He glanced over towards the exit, raised an arm and got a raised arm back, she was standing there and she was reliable and they were still the only ones there.

He got into the leather-clad driver’s seat and took out 00.15 a feeler gauge from his bag, held it against the cigarette lighter filament, then put it into the ignition and turned, turned, turned, heated it up again, turned again, quickly melted down 00.24 the small sharp plastic pegs that would catch, the actual locking mechanism.

She raised her arm.

Voices.

Steps.

He felt inside 00.28 the ignition with a biro, nothing catching now, took out another car key – any of the ones lying at the bottom of the bag, because older Mercedes generally started once the plastic pegs were gone – and checked the clock, 00.32.

They didn’t talk much. They never did.

He had nothing to say to her.

Gabriel drove out of the shopping centre car park, slowly through the southern suburbs of Stockholm in the middle lane. You could see the city behind them and he accelerated into the outside lane, they were heading north, another forty kilometres to go. They normally stopped at the Shell station by the Täby exit, in front of the square glass cabinet for air and water; Wanda normally went into the dirty toilet round the back and prepared herself for the visit and he went into the shop and got his two bottles of Coke from the chiller and stared at the woman behind the counter who looked away as he walked out, who never said anything, who knew his sort, had seen too many young men like him, knew that it wasn’t worth risking that arrogant and superior look, to challenge him and ask for eighteen kronor for the drinks in his hand.

He was sitting in the driver’s seat, radio on full blast, half a bottle of Coke on the dashboard, when she came back from the toilet after twenty minutes. He always tried to check her walking first, see if her movements were normal, then if she had a dirty back from the hard floor – there should be no signs.

They left the motorway and from the exit to Aspsås you could already see the church, the small town, the prison. The almost deserted prison car park, he always went as far in as he could, close to the high wall.

He was eighteen. She was seventeen.

They didn’t go many places, didn’t often go far, but here, obviously they came here.

She straightened her jeans, top, looked for the mirror on the back of the sun visor that wasn’t there, changed the angle of the one on the door instead and smiled into it, then walked towards the grey concrete building as he drove towards the church that loomed a couple of kilometres away – he would wait there until she was ready, by the carefully raked gravel path in front of the rows of headstones in the churchyard.

The gate in the wall, the intercom by the handle, she turned towards the camera and microphone.

‘Yes?’

It crackled, in the way that all loudspeakers by all prison gates crackle.

‘Visitor.’

‘Who for?’

‘Leon Jensen.’

Someone in a blue uniform ran a nimble finger through a list of registered visitors.

‘And you are?’

‘Wanda.’

‘Surname?’

‘Wanda Svensson.’

She was freezing.

There was no wind, bright sunshine bouncing on the concrete, she was sweating and freezing.

There was a click. The door was open.

Heavy steps over to central security and the window and the uniform that belonged to the hands that looked at her.

‘ID.’

It was colder. She was even colder, shaking.

‘Have you been here before?’

‘Yes.’

‘Then you know what to do. Go in there. Take off your coat.’

A stuffy room.

Just one window, with bars.

The wall over there, from the inside.

One two three four ten-kronor coins, both mobile phones and her key ring in one of the small lockers. She locked it, walked slowly over to the grey metal detector, through it, clutching the key to the locker in her hand.

The piercing, monotone noise around her, inside her.

You have to be heard.

Two uniforms stepped forwards, checked the red light that was flashing in the middle of the arch, the one that indicated waist level.

‘Your pockets.’

Freezing, sweating, freezing.

She made a show of searching her front pockets, back pockets, still clutching the locker key in her hand and then went through the metal detector again. The same piercing noise.

Leon’s orders.

You have to be searched.

‘Still waist level.’

One of the uniforms positioned two blocks about half a metre apart, the other held out a long plastic stick; she had to step up onto the blocks, she had to stand still with her legs apart while the plastic stick slid over her hips, the outside of her thighs, the inside of her thighs.

‘Your belt.’

She took it off and put it in a plastic container.

‘Oh … sorry.’

Her hand up in the air, the key inside it, as if she had forgotten it, she looked at them and smiled sheepishly and they stared at her until she had put it in the plastic container beside the belt.

‘Go through again.’

Her chest, a small point slightly to the left, just there, it hurt so much.

She was sure they would see that she was trembling.

She walked through.

But only that.

Not a peep. Not any other sound.

This time only, you have to be heard, you have to be searched, that’s all.

She waited while the uniform that had been standing furthest away let the dog finish sniffing the belt, then she was given it back and pulled it through the loops on her jeans, tried to meet their eyes and then hurried over the concrete floor towards the visiting room that was in the middle, and a bit brighter than the others.

They locked the door from the outside.

She had sat on the chair before. She looked around.

It wasn’t a kind room.

She often did that, divided rooms and flats and houses into kind ones and mean ones. This one was mean. There was plastic under the sheet on the bed and no one would ever sleep there. The yellowed porcelain sink and tap only had cold water. The window was barred and looked out over a strip of grass that led to a seven-metre high wall and unpainted administration buildings.

She wasn’t as cold any more, was barely sweating.

She washed her hands and dried them with some sheets of toilet paper from the roll at the end of the bed. She looked in the mirror, smiled as she always did – her little brother called it her mirror face – checked her lips, eyebrows, hair.

A metal door in a prison has heavy locks that make a very particular sound. When someone unlocks it, there’s a kind of clunking, quiet at first, then louder.

‘One hour.’

He came in.

‘We’ll come for you first, then her. OK?’

The two guards who’d walked in front of and behind him stopped in the doorway, nodded to her and waited until she nodded back – they could go, they could lock the door again.

He pointed to the bed. She sat down, he pointed again, she lay down on her back, the pillow was hard and the plastic chafed her neck when the sheet slipped down.

He looked at her.

She knew how she had to lie when his hands undid her belt, pulled down her zip, pulled off her trousers.

Leon’s hand on her skin, just above the knee, her thigh, it pulled her knickers to the side and made her open her legs wider, his index finger and thumb against her labia.

Around the outside.

‘Relax.’

Inside.

He found it, held it, pulled it out.

A plastic bag, hard to see through.

He weighed it in his hand.

Two hundred grams.

LEON SMILED AT her, the slippery, shiny plastic bag in his hand, but maybe not enough for her to dare to smile back.

‘You’ll come back. Here. In exactly fourteen days.’

Was he pleased, had she done well? She breathed in carefully, hesitated, and again. Then smiled.

‘Put it up. Put it up again, but then dump it before you come. You have to smell. But have nothing up there.’

They were standing close. He wasn’t much taller than she was.

She shouldn’t have smiled.

Leon’s voice, raised again.

‘Whore, d’you understand?’

His movements, angry.

‘Whore, with your stupid fucking smile, you’re to smell but be empty, get it?’

His breath. She nodded.

‘I get it.’

He looked at her. I get it. You don’t get fuck all.

Throughout the week, he’d made sure to mention that he was getting a visit, who was coming to visit, when she was coming again.

Two hundred grams in two-gram capsules.

Within a couple of days, every screw in every unit in Block D would know that a new and strong supply had got into D1 Left and they would all guess that this was how it got in.

He stared at her until she looked away and then put a hand on his own stomach, there was pressure on the sides.

He had taken eight condoms out of the packet that always lay beside the toilet roll at the head of the bed and filled each one with capsules, then swallowed them with cold water from the tap on the yellowing sink, and in a while he would throw up in another sink, in another cell.

‘Reza.’

Österåker prison. One hundred grams.

‘Uros.’

Storboda prison. One hundred grams.

‘Go there now.’

Aspsås, Österåker, Storboda.

A visit to three prisons, every second week.

‘I’m going there now.’

‘They’ve got fines. Both of them. Five thousand in cash.’

‘Five thousand?’

‘Yes. Give them what they’re expecting first. Then tell them that they’ve got fines. You understand, whore?’

‘I understand.’

Leon went over to the metal plate on the wall between the doorframe and the mirror, and touched the red button without pressing it.

‘And Gabriel?’

‘Yeah?’

‘His report.’

He was still very close, his breath just as hot.

‘The kids have sold everything. Ninety thousand. And there’s more from Södertälje and maybe from Märsta.’

Her voice almost a whisper, as if she was reading to herself, it was important to get it right.

‘Twelve houses in Salem and Tullinge. A hundred and forty-six thousand. Two debt enforcements in Vasastan. Fifty-five thousand. Two big barrels of petrol from the Shell station in Alby. Nine thousand. A computer shop tomorrow, I think.’

He nodded. She didn’t know if it was good enough. She hoped so.

‘And … one more thing. It’s important.’

‘Right?’

‘Gabriel said it was important to tell you that your phone’s being tapped.’

Leon had kept his hand by the red button, but now he let it drop, looked at her.

‘Which one?’

‘He said … Gabriel, he said …’

‘Which one, whore?’

‘He said … the one you share with Mihailovic.’

She had remembered. She closed her eyes. His eyes, she didn’t like them.

‘And you are sure, whore, are you sure that’s what he said?’

‘Yes.’

She didn’t want to be near him, his face was so tense. Instead of lashing out, as he turned back to the metal plate between the door and the mirror, he leaned towards the microphone and pressed the red button.

‘We’re done.’

That crackling again.

‘Central security.’

‘Jensen. We’re done.’

‘Five minutes.’

He was finding it hard to stand still, his breathing was irregular and his voice was raised.

‘Are you living there?’

‘Where?’

‘There.’

Every time they were done, when they were standing there waiting, the same question.

‘Yes.’

‘In his room?’

‘Yes.’

‘All the time?’

‘Yes.’

He was standing so close. She was so scared.

‘I moved here. You moved there.’

She waited in the room when he left, one prison warden in front of him and one behind him, down the spiral staircase, into the passage. They stopped in the first room on the right-hand side; he had to be naked when plastic-gloved fingers ran through his hair, felt under his arms, up his arse when he leaned forwards. I’m going to kill them all. A new set of clothes and they carried on down the straight, wide passage several metres under the prison yard, through the locked doors with small cameras that stirred into action as they approached, the corridor to Block D, one floor up, the unit on the left.

He hadn’t eaten all the day, and while the screws got ready for evening lock-up, he’d emptied himself in one of the shower room sinks, handed out the first supplies in the unit and then broken and emptied three two-gram capsules into a mug, stirred the cloudy water for a long time with his pinkie and drunk it before the powder had completely dissolved, then rinsed it down with more water so that it wouldn’t stick to his tongue or throat. He would hand out the rest tomorrow, it wouldn’t cost them anything this time and every prisoner in the corridor would take too much and for too long over the next few days.

This time you’re to be heard, you’ll be searched, that’s all.

He looked out of the window.

You’ll come back. Here. In exactly fourteen days.

It was already light outside.

Put it up again. But then dump it before you come. You have to smell and they’ll stand there with their dogs, doctors and signed documents from the Prosecution Authority. You’ll be searched. But you’ll be empty.

It had been dawn before, but now it was daylight.

As soon as the door had been locked, Leon turned on the lamp that had n

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...