- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

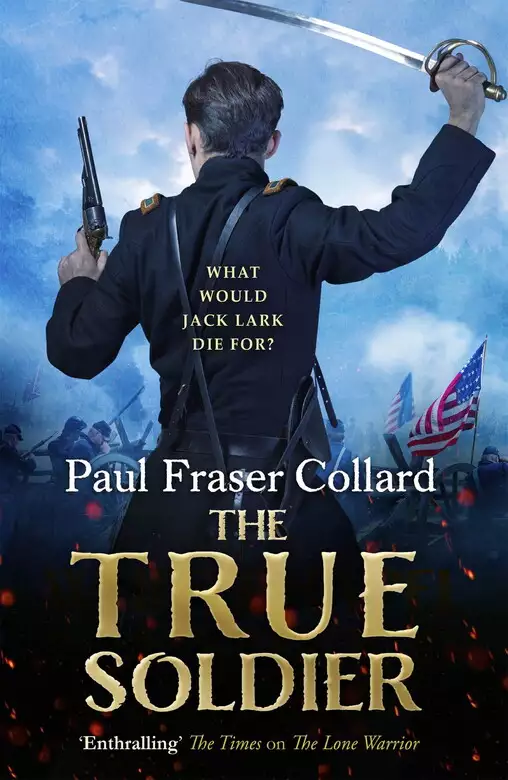

Roguish hero Jack Lark — dubbed 'Sharpe meets the Talented Mr. Ripley' — travels to America to reinvent himself as the American Civil War looms.... A must-listen for fans of Bernard Cornwell and Simon Scarrow.

This ain't the kind of war you are used to. It's brother against brother, countryman against countryman.

April, 1861. Jack Lark arrives in Boston as civil war storms across America.

A hardened soldier, Jack has always gone where he was ordered to go — and killed the enemy he was ordered to kill. But when he becomes a sergeant for the Union army, he realises that this conflict between North and South is different. Men are choosing to fight — and die — for a cause they believe in.

The people of Boston think it will take just one, great battle. But, with years of experience, Jack knows better. This is the beginning of something that will tear a country apart — and force Jack to see what he is truly fighting for.

Release date: July 13, 2017

Publisher: Headline

Print pages: 449

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The True Soldier

Paul Fraser Collard

The Englishman strode down State Street. It had taken an age to get away from the wharf and the throng of longshoremen and officials who had gathered to welcome the latest swathe of immigrants come to Boston for a new life far away from their homelands. He walked away from the chaos with relief. The Plymouth Rock had been crowded, the demand for a berth to Boston far exceeding the carrying capacity of the steam packet, which had left Liverpool over a week before. The voyage had been miserable, his enforced incarceration with the horde made worse by the other cargo that had filled every nook and cranny of the vessel. For the Plymouth Rock had been carrying hope, a commodity the Englishman had left far behind on the blood-soaked battlefields of Europe and beyond.

He pulled his black pork pie hat down lower and quickened his pace as he reached the end of State Street. The ground pitched beneath his boots, his gait uneven as he became reaccustomed to walking on land. The rain might have made the cobbles treacherous, but they still felt wonderfully secure after so long on board the lurching uncertainty of a packet making the Atlantic crossing.

The smell of the place wrapped itself around him as he walked. The fresh, salt-laden air of the sea was replaced with the aroma of food and soot. Boston smelled of people. Not the rancid odour of too many souls kept together in a ship, but the earthy, meaty smell of life in a city.

A crowd of loud, brash stevedores hurried past. A few glanced at the tall Englishman, who met their stares calmly and with no hint of fear. The hard men who toiled in the docks did not worry him. He had fought the Russians, the Persians and the Austrians, along with mutinous sepoys and the army of an Indian maharajah. He knew fear, but he would not feel it standing in the rain on a grey Boston street.

The pause gave him the opportunity to look around and get his bearings. The sky was getting lighter, a brighter thumbprint behind the thick band of clouds indicating the chance of a change in the weather. But the sun would have to fight hard if it was to beat away the gloom, and as he waited, the rain grew heavier. Fine mist was replaced by a deluge, the water coming down in great sheets, bouncing high off the cobbles, the sound of the impact drowning out the noise of the city.

The Englishman shivered, then pulled his greatcoat tighter around him, the thick wool getting heavier as it soaked up the rain. The coat was not his. He had liberated it from a friend’s pack, one of hundreds left unclaimed in the aftermath of the slaughter at Solferino. He doubted anyone in Boston would recognise that it had once been issued to a sergeant serving in the ranks of the French Foreign Legion. Yet that sergeant had been born in the city of Boston, and it was his death that had brought the Englishman to its shores.

It had been a long journey. It had started in a Lombard village crammed full of the dead and the wounded. In the aftermath of battle, he had made a vow to deliver the bloodstained letters of a dying man. It was nearly two years since he had left the battered French army in northern Italy; two years that had seen him journey across Europe before finally returning to his home city of London. He had planned to stay there only long enough to settle a score from his past before buying a train ticket to Liverpool and boarding a ship bound for Boston.

But fate had decided on a different plan. Her name had been Françoise du Breton, and she had been the wife of a French wine trader who spent much of his time travelling across Europe. The Englishman had lavished her with gifts whilst living the finest life London could provide. It had not ended well, and he had been left on the street with just enough money in his pocketbook to buy passage to Boston, and a sackful of regret at what might have been. His last English money had been exchanged on board the packet for dollars, the captain as deft as any shofulman at swindling his passengers with an outrageous rate of exchange.

His heavy carpet bag contained all his possessions. Its sides were stained with salt and darkened with damp, and its handle strained with the weight of the weapon hidden deep inside. His worldly goods had been reduced to the rumpled clothing on his back and the garments stuffed into the bag. He had once been a maharajah’s general, living in a gilded palace and surrounded by beautiful objects. Now he was a near-penniless vagrant with a handful of dollars in his pocket and an unknown future waiting for him.

He pulled the collar of the greatcoat tighter and pressed on. A wagon approached, its horses’ grey coats darkened almost to black by the rain. The Englishman caught the eye of the Negro teamster as he passed, then walked on, following the vague directions the ship’s master had given him. He had been told that he would be able to find the address he sought unaided, the new buildings on Beacon Hill an easy enough saunter from the wharf.

The streets were busier as he approached the end of State Street. The locals, long used to the rain, hurried past, faces hidden behind collars and hat brims pulled low. A short, thickset fellow wrapped in a thick sou’wester knocked the Englishman’s shoulder as he went by, his boots kicking up a heavy spray. There was no apology for the contact, the Bostonian moving away without even a grunt. The Englishman ignored the rudeness, just as he ignored the rain, which was beginning to show signs of lessening, and pressed on, passing by what looked to be a great covered market opposite a grand building with a fine cupola topped with a copper grasshopper weathervane.

After so long at sea, the crowd waiting at the wharf had been daunting. There were too many people, creating too much noise. Keen to avoid another crowd, he turned into a side street, thinking to bypass the busier streets altogether. At the next corner, and with the rain reduced to little more than a drizzle, he paused, dropping the heavy carpet bag to the ground and taking a moment to shake off the worst of the rain. Only when drier did he dig deep into a pocket and pull out the thick sheaf of letters that he had taken from the hand of the dying man.

The pages were crumpled and the string that bound them together was frayed. The text on the uppermost letter, written in pencil in a fine, sloping hand, was faded and part covered by a series of black stains. As the Englishman studied it, his thumbnail picked at the marks, scraping away some of the old blood. It did little to improve their appearance.

A lady of middling years bustled past. She was moving quickly, her dry cape an indication that she had waited for the rain to pass before stepping out. The Englishman saw her gaze wander over him, the rapid appraisal made in less than a second and without her losing a step. The contact was fleeting, but it lasted long enough for him to see her eyes widen just a fraction. It was a common enough reaction. The Englishman was no longer a young man. He was past his thirtieth year, and his lean, clean-shaven face bore a thick scar across the left cheek. The woman would have seen it, just as she would surely have seen the anger that simmered in his hard grey eyes. Some women were put off by the combination, but he knew that to a few he was still handsome, his steely expression and the blemish to his face only adding to his appeal.

He did not linger. He lifted his pork pie hat and ran his fingers through his close-cropped hair before picking up the carpet bag and moving on. For the next hour he wandered the streets of Boston, working his way past the great common and up the sloping streets where he had been told he would find the address that was just about legible on the bloodstained letters.

A watery sun was out by the time he realised he was thoroughly lost. It did little to shift the chill from the air. The Englishman found himself in a series of narrower streets, where the buildings pressed close together. Twice he had asked a passer-by for directions, and twice he had been answered with little more than a glare. On the third occasion he addressed a Negro woman carrying a bundle of sheets. She took one look at him before scuttling away without so much as a word.

He heard the sound of singing. Three men were walking along with arms interlinked so that they blocked nearly the entire width of the street. It did not take a great deal of experience to know that they had been drinking. It was still early in the evening, but the trio appeared to be three sheets to the wind already, the hour clearly no barrier to their excess.

The Englishman looked them over quickly, the appraisal immediate and instinctive. He did not think much to them. They were dressed in matching long dark-blue tunics with trousers of a lighter shade. None of the three were fine physical specimens and all bore the pinched, pale faces of men long used to life in the city.

If he hoped to let them pass without comment, he was to be disappointed.

‘You looking at me?’ The tallest of the three men spoke with a strong Irish accent. He was a long-faced, dark-haired man whose thin beard barely obscured skin covered with a thousand pockmarks.

‘Excuse me.’ The Englishman offered the apology with little sincerity.

‘You’re fecking English!’ The reaction was immediate and it was loud.

‘And you’re a drunk.’

The three men came to a halt. It took a moment for the tallest to extricate himself from his fellows’ arms. The Englishman stood and waited for him patiently. The Irishman paused, then slowly looked him up and down before his eyes focused on his face and took in the amused expression.

‘You think this is funny?’

‘A little.’

The Irishman was sobering up fast. He blinked, then took a step closer. ‘You want me to give you something to laugh about, you slave-loving English maggot?’

The Englishman smelled the sour stink of whisky on the other man’s breath. He was given no time to find a reply.

‘You heard the news, maggot?’ The Irishman was forced to lift his chin so he could look the taller man in the eye.

‘You care to tell me?’

‘You don’t know?’ the Irishman sneered. ‘Where’ve you been? Hiding in the dark, bothering little boys?’

‘I just landed.’ The Englishman’s tone did not alter.

‘And you never heard that those Southern langers have attacked Fort Sumter, I suppose?’

The Englishman raised an eyebrow at what he supposed was momentous news. He did not understand the reference to the fort, but there had been talk aplenty in the London papers of the growing conflict brewing in the United States, a country that appeared to no longer be so united. He had been aware that he was travelling to a place on the brink of civil war. The threat had not bothered him. It was not his fight.

The Irishman did not take kindly to his silence. ‘We’re at war, you dumb fecker. Like it or not, your Southern friends have started this thing. I reckon we’re aiming to finish it. So why don’t you get your chicken-shit English prick down south before one of us feels the need to cut if off and feed it to you.’

The Englishman laughed. He did not mean to. He was no fool. He knew the three Irishmen were spoiling for a fight. But there was something in the man’s insults that he found amusing, and he could not hold back the short guffaw. He had met menacing characters before; men who would make the arsehole of the great Archangel Gabriel himself quiver with fear. This foul-mouthed Irishman was not one of them.

‘You laughing at me now?’ The Irishman’s face twisted. ‘You think I’m being funny, is it?’ A hand shot out, palm first, and thumped into the Englishman’s chest, rocking him back on his heels. ‘You ain’t laughing now, are you, you fecking pox-bottle?’

Another shove. This time it came with enough force to knock the Englishman back a pace. He had paused in front of a hitching post, and it caught him in the small of his back. Instantly, fierce red-hot pokers lanced up and down his spine and into his legs.

The Irishman saw his face react to the pain and laughed. He was still cackling when the carpet bag hit the floor.

‘Back off, chum.’ The Englishman hissed the words.

The warning was greeted with derision. ‘Why don’t you take yourself the feck away, maggot? This ain’t no place for a mewling English eejit.’

The Englishman took a deep breath as he attempted to hold his anger in check. The temptation to fight was starting to mount. ‘Go away. Now.’

‘Why the feck would I do that? You think you can give me orders? We ain’t back home. You English bastards don’t rule the fecking roost round here.’

The Irishman paused to look around him. Already the first onlookers had been drawn to the prospect of a brawl, a rough circle of spectators forming around the three Irishmen and their English victim. The man’s two cronies moved forward to take up position on either side of him. One pulled back his sleeves to reveal thin, pale wrists; he clearly thought to try to prevent blood from spoiling his uniform. The other merely grinned like a fool.

‘Why don’t you teach that English feck a lesson?’ The first catcall came from a fat, dumpy woman who was twisting her apron in her hands as if she were wringing the Englishman’s neck.

‘Shut his mouth, O’Dowd.’ Another shout of encouragement sounded as more people gathered to watch.

The tall Irishman, O’Dowd, nodded in acknowledgement of the instruction. He glared at the Englishman, his mouth twisted. ‘You want to fight, maggot? You want to fecking fight me?’

‘No.’

‘You a coward, then? You got yourself a yellow belly, maggot?’

The Englishman did not reply. He would not waste the breath. He would need it.

‘I think that’s what you are. Nothing but a yellow-bellied gobshite.’ O’Dowd was playing to the growing crowd, which hooted and catcalled in encouragement. He turned his head, preening, enjoying the attention, acknowledging the people he knew with a smile and a wink. When he turned back, the sneer was on his face again as he prepared to insult his victim some more.

The Englishman did not wait to hear it. His fist rose quickly. The blow landed plum on the Irishman’s mouth.

It was a fine punch. It was driven by weeks of frustration and it crushed O’Dowd’s lips back against his teeth. The Irishman’s head snapped back, his jaws cracking together with an audible click before he fell backwards and landed on his arse.

The crowd went silent. For a moment, all present contemplated O’Dowd. Then they went wild.

The smallest of the three Irishmen heard the call for violence. He stepped forward, fists swinging. He was no fool and he punched hard, each blow controlled. The Englishman was off balance and could not twist away. Both of the Irishman’s fists connected with his chest, one after the other, and each hammer blow hurt. The pain was fierce, but it did not stop the Englishman, and he snapped his elbow forward. It was a vicious blow, the kind learned in the rookeries of east London, and it caught the shorter Irishman full in the throat. He fell like a sack of horseshit, hands clasped to his neck, his fighting roar replaced by a choking sob.

‘Fecking hit him!’ O’Dowd screamed the order through bloodstained lips. He was taking his time to get back to his feet, and it gave the third Irishman enough time to take two steps towards his opponent.

The Englishman made no sound as he faced the last man standing. Around him, the crowd bayed with anger, the street echoing to the snarls and cheers of the men, women and children drawn to the brawl. The feral roar goaded the last man into action and he swung at the Englishman, the blow powerful enough to fell an ox.

The Englishman saw it coming. He swayed back and let the punch wash past his face. Then he stepped forward. His fists did not miss, and the last Irishman went down to a short flurry of blows. Each one hit hard, and the last caught him on the point of the chin. He staggered backwards, but to his credit he stayed on his feet. The speed of the Englishman’s fists, though, had near silenced the crowd.

‘You useless feckers!’ The dumpy woman with the twisted apron had seen enough. She had arms the thickness of a girl’s thigh and she carried a pine dolly. It made for a fine weapon and she swung it like a quarterstaff. It hit the Englishman on the back of the head with a sickening thump.

He hit the cobbles without ever seeing who had felled him, blood hot on the nape of his neck as it poured from the back of his head. He barely had time to register what had happened before O’Dowd came for him again.

The Irishman’s boots lashed out. The first caught the Englishman in the gut as he sprawled on the ground, driving the air from his lungs with a great whoosh. He was given no time to recover, and could do nothing but writhe in the dirt as the kicks rained down on him, one after another, blood splattering the rain-slicked cobbles as O’Dowd caught him on the skull.

‘What the devil is going on here?’ The voice silenced the crowd in an instant. It carried authority, its owner clearly expecting to be obeyed.

The Englishman barely heard it. But he did register that the kicking had stopped. He stayed down, the damp cobbles cold against his cheek.

‘O’Dowd! I should have known.’

‘Major, I—’

‘Be quiet.’ The stentorian voice silenced the Irishman. The crowd was hushed. The animal snarls had been replaced by the soft shuffle of boots moving across the ground, the onlookers melting away quickly now that someone had arrived to put an end to their entertainment.

The Englishman eased himself up. His chest hurt and one arm was numb from the pounding it had taken. He got to all fours, then paused, letting his head hang until the pain had receded enough for him to push himself to his knees. Once there, he stayed still, taking in the scene around him.

O’Dowd stood, head bowed, in front of the man who had come to interrupt the brawl. His hands were clasped in front of him so that he looked like an errant schoolboy. The shortest of the three Irishmen, the one the Englishman had felled with his elbow, still lay on his back, his sobs the only sound interrupting the silence. The third man was leaning against the wall of the closest building, his eyes opening and closing rapidly as he fought to stay on his feet.

The Englishman had seen enough and let his head loll.

‘Let me help you.’

He felt strong hands take a firm grip on his upper arms. He was given no time to resist before he was hauled to his feet.

‘Can you stand?’

The Englishman sucked down a breath, then nodded. His body protested, but he had known worse.

He turned his head. The man who had come to rescue him stood an inch or two shorter than the Englishman himself. He was old enough to have salt and pepper in his thick moustache, with more grey at his temples. He was wearing a uniform the same shade of blue as the three Irishmen, but where theirs were baggy and ill-fitted, his was smarter, with gold thread on the epaulettes and bright buttons running down the front.

‘I can only offer an apology for my men’s behaviour.’

The Englishman met the man’s gaze. He noted the accent. His rescuer was American, not Irish, and clearly some kind of officer.

‘Is this how you usually greet visitors around here?’ He tasted blood as he spoke, so he turned his head and spat onto the cobbles.

‘If they’re English, then yes.’ The reply was calm and measured. ‘Here.’ The American officer offered a handkerchief.

The Englishman took it and wiped his lips, streaking the white cotton with red tendrils. He licked the last of the blood away, then ran his tongue around his mouth. A flap of skin had been torn from inside one cheek, the soft flesh caught by his teeth, but the back of his head hurt far more. He raised a hand and pressed the borrowed handkerchief to the wound.

‘Does that hurt?’

The Englishman answered with a withering stare. He kept the handkerchief in place, hoping it would stem the flow of blood. He had seen enough head wounds to know they bled a lot even if the wound was small.

‘Of course, that was a foolish question.’ The American officer pursed his lips and his eyes narrowed. ‘But perhaps it was foolish of you to venture into streets such as these at this hour.’

‘I was lost.’ The reply was clipped.

‘I see.’ There was a moment’s pause. ‘Where were you headed?’

The Englishman considered the question, then dug into his pocket with his free hand. He pulled out the letters and handed them to the American. ‘I’m looking for that address.’

The American nodded. ‘I know it.’ He looked at the Englishman with a raised eyebrow. ‘Are you a friend of the family?’

‘No.’ The Englishman did not say anything else. Instead, he pulled the handkerchief away from the back of his head, considering the amount of blood on it before clamping it back to the wound. ‘I’m just delivering the letters.’

‘You’ve come a long way to make a delivery.’

The Englishman snorted. ‘You have no idea how far.’

The American’s eyes narrowed. ‘Well, I know the address and I know the family. I’ll take you there.’

‘Thank you.’ The Englishman could not hold back a sigh of relief at the offer.

‘May I know your name? I would like to know who I am taking with me.’

The Englishman offered a thin-lipped smile. And so it began again.

‘My name is Lark. Jack Lark.’

‘What will you do with those three idiots?’ Jack asked the American officer. He still held the borrowed handkerchief to the back of his neck as he nodded towards the Irishmen. The one whose throat he had crushed had finally lumbered to his feet and now stood next to his two compatriots so that they formed some semblance of a line. All three looked at the ground.

The officer chewed on the underside of his moustache as he gave the question serious thought. The silence built.

‘Nothing.’ He looked at Jack, finding his gaze and holding it. ‘I am going to do nothing with them.’ He spoke loudly enough for his men to hear.

Jack held back the words that sprang to his lips. He searched the American’s face. ‘Are you their commanding officer?’

‘For my sins.’

‘You ever heard of discipline?’

The American pursed his lips. ‘I have no need to do anything more.’ He raised a single eyebrow. ‘You punished them well enough.’

Jack caught the hint of a glint in the American’s eye. ‘I’d barely got started.’

The American let out a short bark of laughter at Jack’s boldness. ‘I reckon you have that right.’ He looked across at his recalcitrant soldiers. ‘You hear that, boys? Mr Lark took all three of you down. If you hadn’t had help, I reckon A Company could have lost three men.’

The trio looked down shamefaced as their officer scoffed at them.

‘Why did you lose?’ The American stood with his hands clasped behind his back. ‘O’Dowd. Tell me why three of you could not handle one Englishman.’

O’Dowd sniffed. ‘He didn’t fight fair.’ The words were mumbled. The Irishman’s lips were puffy and already blackening.

‘How so?’ The question was snapped back.

O’Dowd struggled to find an answer. His mouth opened, but no sound came out.

‘You lost, O’Dowd, because the three of you didn’t work together.’ The American officer filled the awkward silence. ‘You need to learn from this. You attacked one at a time and so let Mr Lark fight you one at a time. Do that against the Confederates and you won’t be nursing a sore lip. You’ll be dead!’

Jack was hurting too much to find a smile. But he could only admire the American officer’s attitude.

‘Now get yourselves back to your barracks. If I hear you didn’t report back immediately, then I shall let First Sergeant O’Connell teach you the importance of doing what you are told. You know what that means?’

‘Yes, sir.’ Two of the Irishmen murmured an affirmative. The one with the crushed throat offered little more than a half-hearted sob. Then the three of them shuffled away, turning their backs on the Englishman who had knocked them on their arses.

‘Now, Mr Lark.’ The American officer returned his attention to Jack. ‘Shall we find you your address?’

Jack made no attempt to move. ‘Is that what the American army is like?’ He glared at the officer. ‘Is it really that soft?’

The American scowled. ‘We are militia, not regulars.’

‘That doesn’t matter. My question holds.’ Jack removed the handkerchief from his wound. He was pleased to see that the cloth came away with less blood on it this time.

‘It is a fair question.’ The American officer gnawed on the underside of his moustache, the gesture clearly a habit. ‘I don’t think I can explain easily. Not in a way you would understand. My men are volunteers. They have signed up for a cause they believe in, to fight for a country they have adopted and that they love, but not one that was theirs from birth. I admire them for that.’ He fixed Jack with a firm stare. ‘I will not crush such a fine and noble spirit.’

Jack did his best to understand the long answer, but his head was pounding and he wanted nothing more than to sit down and find someone to make him a mug of tea. ‘Still seems to me like your boys need some discipline.’

‘Perhaps.’ The American officer treated Jack’s opinion with respect. ‘But we are not the British army. And this is not England. We do things differently here.’

Jack grunted. He would have said more, but he was painfully aware that he was among strangers. It was not for the first time. Experience had taught him to guard his thoughts and hold his opinions close. And he needed the American officer to show him the way to his destination, so he bit his tongue and forced something that could be said to resemble a smile onto his face.

‘So will you tell me your name? You know mine. I’d like to know who I’ve to thank for rescuing me.’ He asked the question as politely as he could.

The American officer gave his short bark of a laugh. ‘We Bostonians are giving you a first-rate demonstration of Old Bay hospitality, aren’t we just?’ He offered his hand. ‘Major Temperance Bridges of the 1st Boston Volunteer Militia.’

Jack did his best not to smile at the major’s interesting first name and shook the hand offered to him.

‘My parents were Puritans, Mr Lark.’ Bridges was clearly well used to the reaction Jack had attempted to hide. He even offered a half-smile. ‘They were fine people and I thank God daily for their upbringing. Now, are you hale enough to walk? It is not so far.’

‘I’m fine.’ Jack gave the lie easily. There would be time to sit and nurse his wounds, but that time would only come when the letters were delivered.

A Negro footman dressed in a smart dark-green livery opened the door to the fine red-brick townhouse. It was one of a dozen like it. All faced onto the small fenced garden at the centre of the square, where new-leafed trees rustled in the breeze. The houses were tall and clean, and each one was decked out in patriotic flags and bunting, the red, white and blue bright and spring-like.

‘Good evening, master.’

‘Good evening.’ Bridges nodded a greeting at the servant. ‘My friend is here to see your master. Is he at home?’

‘He is, master.’ The footman took a respectful step backwards, and Bridges turned and gestured for Jack to step inside.

‘Are you not coming in?’ Jack saw the officer hesitate.

‘No, I shall leave you now.’

‘Are you not welcome here?’

Bridges considered the question. ‘No, I don’t think I am.’ He looked at Jack and offered his hand. ‘I hope I shall see you again, Mr Lark.’

Jack shook the hand. ‘Thank you for getting me here.’

Bridges waved the thanks aside. ‘I hope your head heals.’ He said nothing more before turning and walking back down the short flight of stone steps.

‘This way, master.’ The liveried footman had said nothing during the exchange. Now he gave a half-bow and gestured for Jack to enter.

Jack did what he was told and stepped inside. The hallway he entered was wide and welcoming. On the floor was a green carpet, and the walls were covered with a number of small paintings, each in a different style of frame.

‘Let me take your bag, master.’ The footman reached forward and removed Jack’s bag from his hand before he could raise a protest. If he wondered at its weight, the thought did not reach his face. ‘Please follow me.’

He led Jack down the hall before turning to his right and into a large, elegant reception room. It was perfectly symmetrical, with a single door opposite the one Jack had just walked through, and two more opposite the two tall windows that overlooked the square. The walls were painted in a mix of warm yellows and mellow greens. A fire burned merrily in the grate, the warmth a wonderful discovery after the damp chill outside, but the room did not smell of burning wood. Instead it smelled of flowers, a crystal vase on a curving side table full of bright spring blooms giving off a powerful aroma.

‘If you will just wait here, master.’ The footman pronounced each word deliberately.

Jack nodded in acknowledgement. His head throbbed with every beat of his heart and he dearly wanted to sit down, but he was wary of perching on either of the two elegant sofas arranged either side of the fireplace.

When the echo of the servant’s footsteps had died away, the only sound left was the heavy tick of a long-case clock

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...