- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

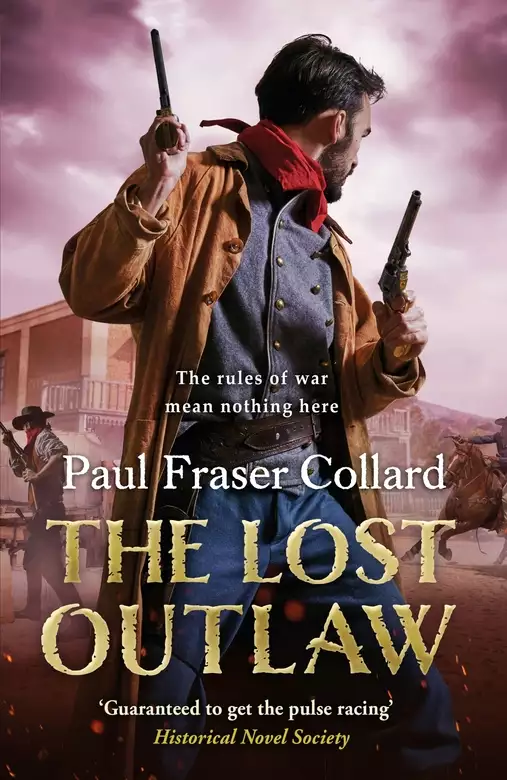

The eighth action-packed Victorian military adventure featuring hero Jack Lark: soldier, leader, imposter. Expect hard fighting, dangerous bandoleros and double-crossing aplenty as Jack arrives in Mexico. A must-read military adventure for fans of Bernard Cornwell and Simon Scarrow.

In the midst of civil war, America stands divided. Jack Lark has faced both armies first hand, but will no longer fight for a cause that isn't his.

1863, Louisiana. Jack may have left the battlefield behind, but his gun is never far from reach, especially on the long and lonely road to nowhere. Soon, his skill lands him a job, and a new purpose.

Navy Colt in hand, Jack embarks on the dangerous task of escorting a valuable wagon train of cotton down through Texas to Mexico. Working for another man, let alone a man like the volatile Brannigan, isn't going to be easy. With the cargo under constant attack, and the Deep South's most infamous outlaws hot on their trail, Jack knows he is living on borrowed time.

And, as they cross the border, Jack soon discovers that the usual rules of war don't apply. He will have to fight to survive, and this time the battle might prove one he could lose.

(P) 2019 Headline Publishing Group Ltd

Release date: July 25, 2019

Publisher: Headline

Print pages: 361

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Lost Outlaw

Paul Fraser Collard

The Confederate officer covered his nose with his bandana as he rode through the slaughter. The bright red and white chequered cloth was usually employed to keep the dust from his mouth, yet this day it served a different purpose: it saved him from the stench of putrid flesh. Bodies rotted fast in the heat of the Mexican sun. These corpses had been left long enough for the stomachs to swell to the point of bursting, and for the open wounds to become rancid, suppurating messes, a feast for the thousands of tiny insects that swarmed over the ruined flesh.

‘Capt’n?’

The officer turned his head as one of his troopers called out to him. ‘What is it?’

‘You seen that?’ The trooper was one of the column’s outriders, and had been the one who had discovered the butchered bodies. He had also been the first to find the foulest of all the depredations that had been visited on the men and women who had accompanied this particular wagon train. Now he pointed at a pair of corpses that had been dragged to one side of the trail. Both had been stripped naked, but it still took the officer a moment to identify the twisted and broken bodies as belonging to women. He had seen enough of the world to know the fate they had endured before their lives had been ended.

‘I see ’em. Now search them other bodies.’ The captain gave the order, then leaned far out of the saddle to spit into the dirt below. It did little to scour the foul taste from his mouth. ‘When you’re done, get all these folk buried. But don’t take too long about it.’

‘Capt’n?’ Another trooper rode up. This man bore the twin yellow stripes of a cavalry corporal on his sleeve above the elbow.

‘Corporal?’

‘We found tracks. Heading south.’

The captain nodded. It was what he had expected. It was not the first ambushed wagon train he had seen, and he knew it would not be the last. The fate of the people now lying in the dirt would be just another footnote in this long and bitter war fought on the frontier, another atrocity to list alongside the hundreds that both sides had inflicted on the other.

He knew that the bandoleros who had attacked this particular wagon train would not linger. They would head due south with their loot. It did not guarantee their safety. Just as they would strike deep into American territory, he would not hold back from chasing them far into Mexico. Indeed, he had permission to do so, thanks to the accord signed between his commanding officer, General Hamilton P. Bee, and the governor of Tamaulipas, Albino López. Yet he could not afford to linger for long. The bandoleros had a head start, and his small command would have to ride hard if they were to catch the perpetrators of this latest massacre.

He kicked back his heels, walking his horse through the bodies that littered the trail. All were naked, the greying flesh the colour of putrid meat. The men who had driven and guarded this particular wagon train had been stripped of everything of value. It left their wounds on display, and he ran his eyes over the corpses, assessing the manner of their deaths with the practised eye of a man who had been fighting since he had been old enough to ride. He could see whom a revolver had shot, and who had died from a blade. Most had had their throats slit, the dark, gaping chasms telling him they had likely been left alive by the wounds taken in the firefight, death only arriving when their necks had been carved open. At least two were headless, the decapitated bodies crowned with great crescents of darkened soil where their life blood would have pumped out.

He reached the last of the bodies, then brought his horse to a stand. He waited there as his men went about the task he had set them, sitting silent, staring at the open trail that stretched out in front of him. To the north, he could see little more than a great swathe of ebony trees smothered with vines, which formed a living, twisted barrier forty to fifty feet high so that he had no sight of the great river that was no more than half a mile away. To the south, there was less for his eyes to look at. A lone mesquite tree and a thicket of thorn bushes was all he could find to break up the expanse of nothingness, the grey-green foliage doing little to colour the wide expanse of dusty drab yellows and muted browns.

Far off on the horizon, he could just about make out a line of distant mountains, their peaks half hidden in the haze so that they were little more than shadows. Scarred into the earth and running east to west were a pair of deep furrows, which thousands of heavily laden wagons had ground into the dirt and which led away for hundreds of yards before he lost sight of them in the shimmering heat haze. It was those wagons that had brought him to this desolate, isolated spot. It was his job to safeguard those who transported the cotton from the Southern states to the Mexican ports, where European buyers queued up to buy it. This time he had failed.

It left him with just one course of action. He would bury the dead and then he would ride south. He would find the bandoleros who had carried out this attack and he would bring them to justice.

His justice.

And his justice was death.

The Confederate outriders spotted the bandoleros just as the sun was setting.

The captain had led his men south, following the trail of the stolen wagons. It had been a hard ride, but he held them to the task, refusing to lessen the pace or even let them contemplate a rest. Only when he judged they were close had he taken his men away from the trail and led them in a wide, sweeping arc that he reckoned would place them far in front of the wagons.

He had found the place for the ambush an hour before. The ground fell away, the trail following it down into a deep gully that ran for a good five hundred yards before the terrain opened out once again. He had dispersed the men, lining them along either flank of the gully, their horses led away and guarded by half a dozen troopers chosen for the task. He had let those that remained choose their own spots. He trusted them. All had done this sort of thing before. He himself opted for a vantage point near the end of the gully. He would be the first to open fire, and he would do so only when the lead bandoleros were a matter of yards away.

He sat with his back resting against a boulder, checking over his weapons. The heat of the day had fallen away so that it was almost pleasant to be sitting there. It felt peaceful, serene and calm. With the sun low in the sky, the few mesquite trees and prickly pear cactus that managed to survive in this barren land cast long shadows across the ground, and the quality of the light changed from searing white to the palest orange, so that the world took on an unearthly feel.

He heard the wagon train long before he saw it. The screech of poorly greased running gear carried far, as did the braying of the oxen dragging the weighty wagons, and the crack of the whips that held them to their Sisyphean task. Only when the train was close did he ease himself forward. He took a moment to check that his revolver was loose in its holster, then aimed down the barrel of his carbine, lining up the shot that would bring fresh slaughter to a day that had already seen so much bloodshed.

Two mounted men led the wagon train. Both were dressed as he had expected, in skin-tight flared trousers open at the sides, paired with jackets made from dark leather. Both wore a sombrero on their heads. There were twenty wagons in all. Each would be heavily laden with ten or more five-hundred-pound bales of cotton, a cargo that was worth a fortune if it could be brought to the cotton-hungry traders waiting at Mexico’s eastern ports. The rest of the bandoleros were spread alongside the train, with one group riding as a rearguard.

The captain made a rough tally as he waited. He counted two men at the front, twelve more scattered amongst the wagons and six at the rear. Along with the men driving the wagons, that made a total of forty. He had thirty-one men waiting along the top of the gully, but he felt not even a trace of anxiety at the uneven odds. He doubted he would take even a single casualty.

His justice would be delivered swiftly.

He sighed, then took a deep breath, settling himself into position. The lead pair were no more than twenty yards away. The gully was less than ten feet deep at the point where the captain waited. It was an easy shot, one he could make a hundred times out of a hundred.

He held his breath, then exhaled softly, releasing half of it. The barrel of his carbine tracked the nearer of the two riders. The distance closed slowly. Twenty yards became fifteen, then ten. When the pair were five yards away, he fired.

It was a good shot. The spinning bullet from the rifled carbine struck the first rider in the side of the head, shattering bone and spraying the second man with a gruesome shower of blood and brain.

The captain was on his feet the moment he had pulled the trigger, his left hand holding the carbine whilst his right drew his revolver. The handgun came up in one smooth motion. There was time to see a moment’s fear on the second rider’s face before he fired.

The bullet struck the bandolero in the chest. He jerked backwards, his arms thrown wide by the force of the impact. The captain fired again, the second bullet striking the bandolero’s chest less than an inch to the right of the first. This time the man tumbled out of the saddle and into the dirt.

All along the gully, the Confederate cavalrymen were pouring on the fire. Some followed the captain’s lead and used revolvers. Others switched to shotguns, and the air was full of the explosive blast of their firing. No matter their choice of weapon, every trooper hit his target, and the bandoleros were gunned down without mercy. The sounds of the shots blurred together so that they merged into one long-drawn-out roar. Underscoring it all were the cries of the dead and the soon-to-be dead.

‘Hold your fire, goddammit!’ The captain shouted the order, then scrambled over the lip of the gully and down the slope. The ambush had lasted less than half a minute. Not one of the bandoleros was left in the saddle or seated on a wagon.

He reached the bodies of the two men he had shot. One was clearly dead, his shattered skull unloading its contents into the sandy dirt that covered the ground. The second, the one shot by his revolver, was still alive. He lay spread-eagled on his back, gazing up at the sky whilst his mouth moved in a fast, desperate prayer for deliverance.

The captain stood over the man. He paused, making sure the bandolero was looking directly into his eyes. Only then did he move his right hand, aiming the revolver. The bandolero’s prayer increased in tempo, the words pouring out of him in a sudden terrified flood. Then the captain fired and the prayer was ended.

There was nothing else to see, so he walked back along the gully. He fired twice more, killing two men too badly wounded to live for long. He found what he was looking for draped across the seat at the front of the second wagon in the now stationary line.

The bandolero who had been driving the wagon was still alive. He had been hit twice, once in the shoulder and once in the head. Neither wound would kill, even though the bullet that had grazed his scalp had released a great torrent of blood. It had left the man dazed and hurting, but alive.

‘Get yourself the hell down.’

The bandolero blinked back at the captain, too dazed to understand.

‘Goddammit.’ The captain hissed the word under his breath, then holstered his revolver and approached the wounded bandolero. He took hold of the man’s shirt, then half dragged, half threw him off the wagon and on to the ground.

‘Don’t you goddam move.’ He gave the order, then stood back and waited.

All along the wagon train, his men were going about the same merciless task of searching the bodies for any bandolero left alive. Gunshots cracked out every few moments as the killing continued. Around him, the oxen brayed and fussed, but he ignored them, just as he ignored the riderless horses that pawed anxiously at the ground or roamed along the gully. His men would round them up when the bandoleros had been dealt with.

‘Capt’n, we got ourselves one of the sons of bitches.’ The corporal delivered the news to his officer as he approached. Two troopers followed, guarding a dishevelled, bloodied bandolero. The man looked pathetic. He had been shot in the arm, the wound now covered by his free hand. His face was bloodied, the flesh puffy and bruised from the blows it had taken from the fists of the men who now held him fast.

‘Ramirez!’ The captain summoned one of his men fluent in Spanish.

‘Jefe?’ Ramirez had already wandered over, expecting to be summoned.

‘Ask these sons of bitches who they work for.’

Ramirez nodded. He posed the question in fast, fluent Spanish. Neither prisoner answered.

‘Corporal.’ The captain nodded.

The corporal needed no further instruction. He was a big man, easily over six feet tall, with broad shoulders and long, powerful arms. He knew what his captain wanted.

The bandolero with the bloodied arm looked up as the corporal came to stand in front of him. His mouth opened, but whatever words he wanted to utter were rammed back down his throat as the corporal smashed his large fist directly into his mouth. More punches followed, the corporal throwing his full weight behind each one. The men holding the bandolero gripped him hard, keeping him upright as the blows came without pause, hammering first into the Mexican’s head, then into his chest and stomach.

‘Enough.’ The captain called a halt to the battering. ‘Let him go.’

The bandolero fell to the ground as if his bones had been pulped into so much mush. The corporal stood back, chest heaving with exertion, knuckles speckled with blood.

‘Ramirez.’ The captain nodded to his Spanish speaker.

The question was asked again. This time it was addressed to just one bandolero. This time it was answered, in a gabbled, terrified flood.

‘They’re Ángeles,’ Ramirez translated.

The captain grunted in acknowledgement. He knew the band Ramirez referred to well enough. There was more than one gang of bandoleros who thought nothing of attacking the wagon trains bringing the cotton from as far away as Louisiana and Arkansas, but the one known as Los Ángeles – the Angels – was the largest and most notorious. It was said that its leader, Ángel Santiago, had as many as three hundred followers now, his men well fed on the wagon trains that he ordered them to attack. He was said to be a monster, a killer who had no notion of mercy and who would never take a prisoner. The locals referred to the gang as Los Ángeles de la Muerte. The Angels of Death.

‘Bury them.’ The captain had learned enough. He gave his last order, then turned away. The sight of the Ángeles sickened him to the stomach.

His men understood his order, and hurried to obey. It took them a while to dig the two pits to the side of the trail; long enough for the bandolero the corporal had beaten to come back to consciousness.

The two Ángeles were dragged towards the pits. Both knew the fate that awaited them, and both fought against their captors, their cries and pleas greeted with blows, slaps, jeers and laughter. Still they struggled. Both were weeping now, their tears cutting channels through the dirt and blood that smothered their faces. The Confederate cavalrymen gave no quarter. The two bandoleros were beaten into submission, fists and boots used without mercy until they were forced into the freshly dug holes in the ground.

The Confederates started to shovel the soil around their two victims. The captain stood by, listening to the sobs and muttered prayers of the two men he was committing to a horrific death. Both were weeping, and emitting a heart-rending series of moans and pleas as the soil was piled higher and higher. When it reached their necks, one of the troopers stepped forward, compacting the freshly turned dirt with his boots. Those watching laughed as he turned the task into a jig, their laughter doubling in volume as he deliberately kicked the nearly buried men in the head and face with his heavy boots.

Only when he had finished was the last of the soil shovelled into place. The Confederate cavalrymen took care not to pile it too high, stopping when it was firmly in place around the bandoleros’ necks. Their heads were left free.

The captain called for his corporal and gave the order.

‘Mount ’em up.’

‘Capt’n.’ The acknowledgement was brief. The troopers moved to obey, not one of them glancing back at the two men they had just incarcerated in the dusty soil.

The captain alone stayed where he was. He looked at the two men in turn. He was not moved by their tears or their whimpers. They faced a slow and painful death. The insects would come first, the tarantulas and the scorpions, the ticks, the fleas and the flies. None would kill, no matter how many times they stung or bit. That task would be left to the bigger animals that would follow: the coyotes and the rats that would begin to devour the flesh that had been left for them, and the rattlesnakes, copperheads and rat snakes that would sense the warm objects and come to investigate.

The two men would provide a welcome feast for the animals that called this forlorn, empty wilderness a home. That feast would continue until nothing but bone was left behind, the two men reduced to a pair of sun-bleached skulls. But the warning would endure, long after they were dead.

The captain turned his back on the two bandoleros and walked to his horse. His men were ready to move out, just as he had ordered. Some would drive the wagons that had been captured, whilst others would ride out ahead to scout the trail. They would proceed slowly, taking every precaution, wary of any more Ángeles who might dare to venture close. Not one would dwell on the fate of the men who had been left behind to die. Today it was their turn to administer the cruel, merciless justice of the frontier. Tomorrow they could be the ones on the receiving end of such a fate. Such was the bitterness of their war. Such was the destiny of the men who fought it.

The captain led his column north. Behind him he heard the first terrified shouts and cries as the men left buried up to their necks tried desperately to keep away the insects that had arrived to begin their long, tortuous deaths.

Natchitoches, Louisiana, St Valentine’s Day 1863

The man sitting in the dining room’s corner seat eyed the room warily. He had not bothered to learn the name of the town he was in, for he would not linger there long. It was a place to rest for a few hours before he resumed his wandering, nothing more.

The settlement was prosperous, he knew that much, the main street lined with fine Creole town houses with iron balconies. He cared little for the aesthetics. He cared only for practicality. The town’s location on El Camino Real de los Tejas, one of the main trade routes through Louisiana, meant there was enough passing custom for it to have a livery, and so his horse could be fed, watered and brushed. It was not out of compassion for the animal that he spent the last of his grey Confederate dollars on its care. It was out of necessity. He would need the beast if he were to continue to travel. Without it he would be reduced to nothing more than a tramp roaming the countryside. He might not have a destination in mind, but he was more than a homeless vagrant. Much more.

Or at least, he had been.

He had wandered for months now. The summer that had come after the bloodshed at Shiloh had passed easily enough. The warm weeks had been spent travelling across the Southern states, the days passing in a lazy torpor, the money in his pocket allowing him to rest and eat without interference. The autumn and winter that had followed had been harder. His supply of ready cash had dwindled, and he had been forced to find work, a succession of odd jobs in out-of-the-way places allowing him to continue to head south and west. He kept away from the war and, as much as he could manage, away from people too. He avoided both with assiduous care, wanting nothing to do with either. For he craved peace and solitude, or at least that was what he told himself as he spent night after night by his lonely campfire with no one but a stolen horse for company.

One of the logs burning in the fireplace spat out a fat ember with a crack loud enough to turn heads towards its fiery grave. The man in the corner seat did not so much as twitch. A man who had fought on a dozen battlefields was not startled by such an innocuous sound. Yet he still reached out to pull his repeating rifle towards him, keeping it within easy reach. Next to it was a Confederate infantry officer’s sabre in its scabbard. On his right hip, the man wore a fine Colt revolver with ivory grips, the metal buffed and polished so that it shone like silver. He was never far from the three weapons; the tools of his trade always at hand and ready to be used.

The hum of conversation began again almost immediately. The simple dining saloon was almost empty, but there were enough men present to fill the space with grunted discussion and the scrape of metal on plate. Few would loiter there. It was a place for consuming the fuel needed to survive, not for enjoying a leisurely dinner.

The man in the corner seat used a wedge of dry day-old bread to mop up the last of the juices from the thick, fatty slices of bacon he had devoured. It felt good to have the food settle in his belly, even if it had cost him fifty cents, with another ten spent on the bitter coffee that tasted nothing like the thick, tarry soldier’s tea that he preferred. Still, it was an improvement on the hardtack, desiccated vegetables and salted meat that was his usual diet. If he were being honest with himself, he had stopped at the backwater town for reasons other than just the care of his horse. There were times when a man needed warm food inside him.

There was little to see in the dining saloon. The simple pine tables were battered and scuffed from years, even decades, of long use. There was scant decoration on the walls, save for the large chalkboard above the fireplace that listed the fare on offer and its price. For a man who had once lived and eaten in a maharajah’s palace, there was little to recommend it. But the food had been hearty, if not so fresh, and the truth of it was that the man in the corner seat had barely a dollar left in his pocket and had to live on the means at his disposal.

Food consumed, he stretched his legs out in front of him and belched softly. For once, he felt full, and he patted his belly to ease the arrival of the heavy meal. He burped for a second time, keeping the sound soft, unlike so many of the other men in the saloon, who shovelled their meal into their mouths at pace, then belched with the volume of a bullock being led to the slaughterman.

There was just a single woman in the room. The man in the corner seat had known she was a whore the moment he had entered the room. She was dressed to provoke interest, wearing nothing more than her lace-edged white underclothes paired with a scarlet bodice that had been left with its uppermost lacings undone to display enough flesh to arouse. But it would take a needy man indeed to be attracted to the display. The whore strolled listlessly around the room, her hands caressing a shoulder here or sliding across a table there. All the patrons, bar the man in the corner seat, had been approached. Clearly none had voiced enough of an interest to keep the woman from working the room, as she waited for men to finish eating so that she could earn the first coins of that evening’s pay.

Eventually she approached the man at the corner table. He had known she would, his arrival noted by the woman as carefully as it had been by the old man who had delivered his food and taken his money. He was just glad she had allowed him to finish his meal before she bothered him.

‘Are you lonesome, sir?’

The man in the corner seat said nothing. The girl came closer in what he supposed she thought to be an alluring way, but which to him looked like she was half cut. He studied her eyes, noting the glazed look and the widely dilated pupils. He had been raised in a gin palace in the East End of London, his first friends the whores his mother had allowed to work the crowd who bought her watered-down gin. Enough of them had dulled the pain of their lives with opium, and although he was thousands of miles from his childhood home, he recognised the look of a woman, long past the early flush of youth, who had turned to whatever local substance was available to get herself through another night of being humped by any man with enough coins in his pocket to pay for his pleasure.

As she came closer still, he could see the lines around her eyes, her age revealed in the cracks and fissures gouged across her forehead. She smelled as cheap as she looked, her overpowering perfume catching at the back of his throat. She opened her mouth to repeat her unsubtle question, but stopped abruptly. Her mouth remained open as she contemplated the hard grey eyes that looked back at her, then she turned on her heel and sashayed away.

The man in the corner seat was not sorry to see her go. But he did wonder what it was she had seen that had turned her away so swiftly. He knew he was no ogre, despite the thick scar on his left cheek that played peek-a-boo from behind his beard. There had been enough women in his life for him to realise that some found his battered charms attractive. But it had been a while since any had come to his bed, and he wondered if he were now repulsive; if there were something of what he had seen, of what he had done, reflected in his gaze.

He ran a hand briskly across his head, his fingers tingling as they touched the close-cropped bristles, and surveyed the room, checking for a threat. He was always alert, always looking for danger. He no longer knew why, but he could no more stop watching than he could stop breathing. It was who he was now.

It was time to go, but before he could rise, a young couple entered the room. Both were well dressed, the boy in trousers and shirt and a fine bright-red waistcoat that reminded the man in the corner seat of the flash boys of his youth. On his hip was the inevitable six-shooter, the revolver kept snug in a brown leather holster, and as he entered the room, he pulled a wide-brimmed black felt hat from his head. The girl was pretty enough to turn heads, with long dark hair worn in a neat braid that hung over one shoulder. Her dress was dark green and patterned like tartan, with white lace around the neck. To the man in the corner seat she looked a thousand more times attractive in her simple, respectable dress than the whore who paraded around with a large portion of her breasts on open display.

The pair whispered to one another, the conversation taking no more than a few seconds, before they separated, the boy walking into the room whilst the girl sat at one of the many empty tables near the door.

The man in the corner seat watched the boy – he could not think of him as anything else – as he approached a diner attacking half a cooked chicken with his pocketknife. He judged the lad to still be in his teens, and certainly well short of his twentieth birthday. It was rare to see a boy of his age. Most had left to join the Confederate forces that were fighting the armies of the Northern states.

He had heard tales of lads as young as eleven or twelve joining up, despite the age of enlistment being eighteen. He smiled as he remembered a pair of underage twins in the regiment in which he had served who had found a cunning way to enlist without lying. The boys, aged sixteen, had put a slip of paper into their boots on which they had written the number 18. When questioned about their age, they had been able to truthfully reply that they were ‘over eighteen’. His smile faded. One of the twins had been killed crossing the city of Baltimore before the first battle in the War Between the States had even been fought. His death had meant nothing; had achieved nothing. He did not know what had become of the second twin, their parting coming on the battlefield as their battered regiment had begun a long and hazardous retreat back to Washington.

‘Excuse me for interrupting your food, sir,’ the lad said to the man tucking into his chicken dinner, ‘but do you know the way to Shreveport?’

The man, a heavily bearded fellow in a red checked shirt with gravy stuck to his whiskers, scowled at the interruption to his meal and shoved a great chunk of chicken flesh into his mouth in lieu of a reply.

‘I’m sorry to disturb you and all, but we’re looking for our father. My sister and I, well, we heard he was there. We need to find him. You see, our mother, she passed and he doesn’t know. We need to find him so we can tell him.’

The man looked the boy straight in the eye. ‘It’s north of here,’ he mumbled, spitting out a morsel of chicken, which became caught in his beard where it enjoyed a reunion with a large dollop of gravy. ‘Fair way aways, though.’ He rammed another hunk of chicken into his mouth. ‘If you head north, you’ll find it easy enough. Plenty of folk know the way to Shreveport.’

‘Thank you kindly, sir.’ The boy held his hat across his belly, nodded his thanks, then turned and walked back to take a seat opposite his sister.

The man in the corner sea

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...