- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

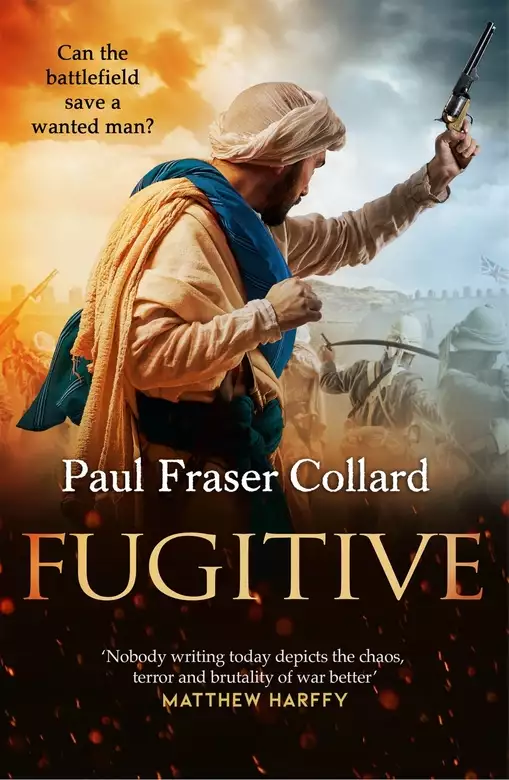

In this ninth action-packed Victorian military adventure, Paul Fraser Collard's roguish hero Jack Lark - soldier, leader, imposter - crosses borders once more as he pursues a brand-new adventure in Africa.

After five years away, Jack Lark - soldier, leader, imposter - is once more called to fight . . .

London, 1868. Jack has traded the battlefield for business, running a thriving club in the backstreets of Whitechapel. But this underworld has rules and when Jack refuses to comply, he finds himself up against the East End's most formidable criminal - with devastating consequences.

A wanted man, Jack turns to his friend Macgregor, an ex-officer, treasure hunter and his ticket out of England. Together they join the British army on campaign across the tablelands of Abyssinia to the fortress of Magdala, a high-stakes mission to free British prisoners captured by the notorious Emperor Tewodros.

But life on the run can turn dangerous, especially in a land ravaged by war . . .

Praise for the Jack Lark series:

'Brilliant' Bernard Cornwell

'Enthralling' The Times

'Dusty deserts, showdowns under the blistering sun, bloodthirsty bandoleros, rough whisky and rougher men. Bullets fly, emotions run high and treachery abounds in The Lost Outlaw... an exceptionally entertaining historical action adventure' Matthew Harffy

'I love a writer who wears his history lightly enough for the story he's telling to blaze across the pages like this. Jack Lark is an unforgettable new hero' Anthony Riches

'You feel and experience all the emotions and the blood, sweat and tears that Jack does... I devoured it in one sitting' Parmenion Books

'Expect ferocious, bloody action from the first page. Fast-paced, compelling, and with more villains than a Clint Eastwood classic, this unputdownable novel strongly reminded me of that legend of western writers, Louis L'Amour. A cracking read!' Ben Kane

(P)2020 Headline Publishing Group Ltd

Release date: August 20, 2020

Publisher: Headline

Print pages: 340

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Fugitive

Paul Fraser Collard

The sun rose. It cast long shadows over rocks and distant mountains, and coloured the sky with great streaks of fiery orange that pushed back the grey of night to bring light out of the darkness. Warmth was returned to the barren lands; life and illumination replacing the blackness and cold of the night.

‘Only God could create such beauty in such a place as this.’

‘I beg your pardon, master?’ The servant who led the small party of three men turned in the saddle.

‘I said that this is God’s work, Negusee.’ The man who had broken the silence spoke again, his voice louder as he addressed the servant for the second time. It was a good voice, a strong voice, the kind that could fill every inch of a church’s nave. Yet that day it echoed off rocks, with no one to listen to it save for the pair of tired and chilled servants borrowed from Consul Cameron’s retinue, and three dust-shrouded mules.

The Reverend Henry Aaron Stern had not chosen the easy path. He served his God in a different way; one that would see him spend his days not in the quiet tranquillity of an English parish, but on the dusty hillsides of the chaotic land of Abyssinia. Now, as he watched the sun rise, he marvelled at the splendour of the wild country that had been his home for so long, and which beguiled and terrified him in equal measure.

He rode on, his body swaying to the movement of the mule beneath him, savouring the peace, the only sound the mesmerising scuffle of hooves on the stony ground. These lands were majestic in their lonely beauty. Mountains filled the distant horizon, their tops shrouded with clouds formed from a beguiling palette of greys now that the sun was rising. The road he followed was well used, the armies that traversed the land trampling the dust and rocks of its surface into a fine powder. It was a good road, solid, built on strong foundations, and it followed the undulations of the land, weaving past boulders too large to be blasted out of its path.

Ahead, the first rays of the sun glinted off the slab-faced wall of a monolithic mountain, the light concentrated into a single, dazzling beam that conjured the image of a star fallen to earth. The notion made Stern smile. For a moment he was not a dusty missionary, but a king following a glittering star; his journey not to witness the birth of the son of God, but along a winding road that would see him returned to the city that had taken him in, clothed and guided him. London had provided a future for the poor Jew from Hamburg, who had arrived into its grasp some twenty-four years before with nothing but rags on his body and hope in his heart. Now he longed to return there. His time in the wilds of Abyssinia was over.

His mule stopped moving, then raised its tail. The sound of shit splattering onto the ground was loud in the early-morning quiet. It was enough to make him laugh, the noise, and the stink that followed, a reminder that he was still bound to this hard land of rock and granite, for a while longer at least.

Bowels emptied, the mule resumed its slow, hypnotic gait. Stern let it take its time. There was no point hurrying, the journey he was on too long and too arduous for anything other than an easy pace. He did not mind that it would be months before he would see London again. He was quitting Abyssinia with a full and righteous heart, for he knew that his work here was done.

The rising sun caught the water of a distant lake. It was as smooth as glass and reflected the line of mountains that surrounded it, a perfect mirror image caught upon its surface. It was beautiful, yet Stern felt nothing but sadness. For despite the untamed beauty of its landscape, Abyssinia was an ugly place, coloured not with the splendour of its natural bounty, but with the blackness of anger and the dirty taint of blood.

He shivered at the thought. He had been drawn to this land and its people, his life as a missionary for the London Society of Promoting Christianity amongst the Jews giving his existence the purpose it had needed. His service had brought him here over three years before, to the shores of a country that needed Christ’s teachings like no other he had found. Christianity had been his own saviour and he had wanted nothing more than to bring its teachings to others. He had first heard tales of the lost Jews of Abyssinia many years before he had arrived there. The country was Christian, but there were still great swathes of the place that clung to their own, false faiths. He had wandered the country, spreading the word of the one true God amongst the Jews, the Mussulmen and the pagans he had found. Two years earlier, his funds had run out, so he had returned to London to raise more, even publishing an account of his time amongst the heathens to help finance his return. That book, Wanderings Amongst the Falashas, had earned enough money to return him to Abyssinia the previous year.

Now he was leaving for a second time.

‘My work here is done.’ He spoke the words aloud. He liked the way they sounded.

‘Master?’ Negusee rode in front of Stern and now twisted in the saddle to look back at his temporary master.

Stern caught a hint of disdain in the retainer’s expression. ‘I said my work here is done, Negusee, and it has been a success. I say that without pride.’

‘Yes, master.’

‘How many have I converted to the Christian faith? Why, I believe I have lost count.’ Stern chuckled at his own words, taking comfort from hearing them. ‘The Return to the Falashas, I think that is what I shall call it.’

‘Master?’

‘My next book, Negusee. It will be the perfect companion to Wanderings. The title has a suitable ring to it, I believe.’

‘Yes, master.’ Negusee turned to face the direction of travel once again.

‘Or perhaps The Return to the Land of the Mad King.’ Stern spoke quietly, as if frightened of being overheard. It would be an accurate title, although not one he would dare speak of until he was far from the lands of the great Emperor Tewodros. For Tewodros, or Theodore as he was more commonly known in England, was indeed a mad king, a quixotic and dangerous mystery of a man if ever there was one. Stern had never been formally presented to him. Still, he had heard and seen enough to have a firm opinion of the man’s character.

At times Tewodros was said to be great company, welcoming European missions into his pavilion, quizzing them on matters of politics and asking a thousand questions about the countries of Europe. He was known to be both humorous and generous; an affable, scholarly man who thirsted for knowledge of the world in which he wanted his newly conquered land to take its place. Then there would be a sudden change. Stern had heard it said that there was never a time when the catalyst for that change had been obvious. But the swift anger and raging temper that had followed was said to be terrible to behold. It was a temper that inevitably led to death.

Stern knew Tewodros’s story as well as any man; the tales and legends that detailed his rise to power were told in every village across the land. Little was known of his early years, other than that he had emerged around twenty years before as a petty chieftain called Kasa Haylu in the lowlands to the west of the country. Early victories over local rivals set him out as a man to be feared. His power grew, as did his reputation as a leader touched by the hand of God himself. That reputation earned him the hand of Tewabech, daughter of Ras Ali, regent to the Emperor Yohannes III. Yet Kasa was not yet done. When the Empress Menen left the capital of Gondar undefended, he struck, taking the city as his own. Many battles followed as the armies of the fiercely independent regional nobility sought to retain their power. Kasa won them all. The more he won, the more warriors and chieftains flocked to his banner. When, eight years before, in 1855, he defeated his last opponent, the Dejazmach Wude, he proclaimed himself emperor, taking the title of Tewodros II.

Yet his reign was not to be a happy one. He defeated the last independent region, Shewa, shattering their army and leaving himself as the only power in the land. Yet the patchwork of provinces that made up Abyssinia, so long independent, rose one after the other, forcing the new emperor to put down a string of rebellions as his rule was challenged from every quarter. His army crushed each and every show of resistance with a ruthlessness that would shame even the great Khans of the East, yet he never succeeded in achieving a lasting peace. Instead he was forced to kill again and again, slaying any who stood against him.

And he had been driven quite mad by the process.

Stern shivered, not just from the chill in the morning air. He heard the sound of a shepherd’s reed pipe coming from far off in the distance and concentrated his mind on it, seizing on the distraction to divert his thoughts away from the brutality of Tewodros’s reign, brutality that he had seen with his own eyes. The gentle melody echoed off the rocky ground, the sound fluctuating and undulating so that he had to concentrate to hear it clearly.

As he rode on, he thought about the changes wrought on Abyssinia. So much had changed in the eight years since Tewodros had risen to power. The long years of bloody decline had started with the loss of the emperor’s wife, the beautiful Empress Tewabech. Each year that had followed had seen at least one more rebellion. All were quashed without mercy, the perpetrators, their followers and their families executed. Tewodros’s land was filled with blood, his throne held up by a foundation of corpses. Invasions had followed, the Egyptians raiding the Abyssinian lowlands without pause. Betrayals had become almost constant, even men Tewodros had appointed himself turning against him. For now, he clung on to his power, but he was having to fight harder and harder to retain it as each year passed.

Stern had witnessed the emperor’s reaction to such a betrayal at first hand. He had been part of an audience attending the trial of one of Tewodros’s own senior commanders. The man, once trusted to lead one of the emperor’s armies, now stood accused of plotting against him. For once, Tewodros had been icy calm, his temper contained. Yet that had not stopped him from ordering the man’s right hand and foot to be cut off before he was left as food for the hyenas. Blood and mutilation. Torture and death. Such was the currency of Tewodros’s reign.

Stern felt a rush of bile surge up from his gut as he relived the moment of dismemberment. The memory of the events he had witnessed haunted him. He had prayed for guidance and for the strength to remain in Abyssinia to do God’s work. He had heard nothing by way of a reply. That silence had been drowned out by the screams of the emperor’s victims that resonated in his head, and had left him bereft. So he had made the choice to leave while his own limbs were still attached to his body.

The small party rode on in silence. The plateau of Wegera stretched away from them. The great expanse was coloured with earthy tones, the browns of the soil and the greys of the rocks broken by great swathes of stunted bushes that bore a smattering of tiny leaves alongside hundreds of huge thorns. The only sign of the hand of man was the great road they followed, which would take them northwards to the coast. It was another legacy of Tewodros’s reign, the emperor’s obsession with cannon and all other artillery leading him to construct the beginnings of an expansive network of roads that criss-crossed the country.

Ahead, spread across the plateau, was a collection of tents. All were black, except for one. That single red pavilion stood out like a beacon. Stern’s heart sank. Only one man had a tent the colour of blood. Tewodros. Emperor of Abyssinia. Descendant of Solomon and his wife Sheba. Murderer. Killer. And master of all.

‘God is our refuge and our strength, an ever-present help in trouble.’ Stern muttered the words under his breath as he pulled back on his reins and brought his mule to a stand. ‘We will not fear, though the earth give, and the mountains fall into the heart of the sea, though its waters roar and foam and the mountain quake with their surging.’

He looked around. Silence surrounded him. No one else was on the road save for his little party.

‘I think we shall divert to the east.’ He shifted in the saddle and made a play of searching for another route. He did not look at Uttam, the second servant from the consul’s staff, who had been ordered to accompany him on his long journey to the coast. The old man had plodded dutifully in his wake for days without uttering a single word. Now he looked back at Stern with doleful eyes that spoke more eloquently than any words.

‘Master, that is not possible.’ Negusee still led the three. Now he turned his mule around to face his temporary master, a forced smile plastered across his face. ‘We must pay our respects to His Majesty. To not do so would be to treat His Majesty with the utmost contempt. Men have been put to death for much less.’

‘Come now, Negusee, I do not imagine he would mind. We have a long journey ahead of us and I am not sure we have the time to delay.’ Stern hummed and hawed, hoping that the servant could not hear his fear.

‘No, master.’ Negusee’s smile faded. None of it had reached his eyes, and now they betrayed their owner’s disdain. ‘We must pay homage to the emperor.’

Stern made no attempt to move. Fear was flooding into his gut, then heading lower so that he could feel it squirming into his bowels. He knew Negusee was speaking the truth. To pass the emperor by would be a dreadful insult, one that could earn its perpetrator a brutal death. His mind conjured the image of a man being held down. Once again he heard the screams as first a hand, then a foot was sliced from the man’s body. He saw the blood – there had been so much blood – pouring out of his wrist and ankle like water from a jug. He had screamed the whole time, even as he was dragged from the tent, a great snail trail of gore left in his wake.

The image gave Stern the heaves, and he gagged. The burn of vomit hit the back of this throat, acrid and sharp. He swallowed it down with difficulty, then burped, the foul taste of bile filling his mouth.

Negusee was watching him, his face expressionless.

‘We shall pay the emperor our respects.’ Stern spoke the bitter words. His throat still burned, so he reached for his canteen. It took a while for his shaking hands to remove the stopper. He drank the water, relishing the cool liquid as it ran over the scalded flesh at the back of his throat. He swallowed it down, then drank again, scouring away the taste of fear.

‘Lead on, Negusee.’ He gave the command in a firm voice. The water sat heavy in his stomach. He burped again, yet it did nothing to relieve his biliousness.

They saw the first of Tewodros’s warriors as they rode closer to the tents. These were not soldiers, not as Stern knew them. They were wild men, hewn from this harsh land, their spears and swords carried with the casual expertise of men well versed and practised in their use. They did not know him, these killers. But they saw his white face and they knew that their master’s hatred of the Europeans had been growing stronger with each passing day. So now they mocked Stern as he rode towards the great red pavilion. They cursed him and spat at him, spears shaken and pointed as if about to strike him down.

Stern forced his spine to straighten. He tried to think of Christ shuffling through the crowd on the way up the hill at Calvary. He himself carried no cross, yet his fear was just as heavy as any wooden spar, and it took all of his strength to make himself sit straight-backed on the mule and hide that fear away.

Tewodros’s warriors pressed closer. He felt hands scrabble at his arms and legs, fingers like claws digging and jabbing. All the while he was bombarded with abuse, words he did not understand bellowed at him. The clamour increased with every step his mule took. Shouts. Jeers. Hatred unleashed.

He reached the red pavilion. Still the crowd pressed around him. At any moment he expected to feel the sharp stab of a blade slicing into his flesh. Inside his belly, fear was taking hold. Muscles that had trembled now shook. Bowels that felt filled with water almost gave way, and he had to clench his buttocks tight lest he void them there and then.

More soldiers lurched out of the pavilion. He saw at once that they were drunk. They staggered towards him, anger flaring as they saw a white face in their midst.

‘We must find some shade.’ Stern blurted the words. He had to shout to make himself heard, such was the furore that surrounded him.

‘Master?’ Negusee was close enough to hear, yet still he questioned the white man he had been ordered to serve.

‘We need shade!’ Stern shouted, desperation and fear revealed without a care. He did not know what to do. Never before had he faced such hatred directed at him and him alone. He looked around. All he could see were angry faces. All he could see was their loathing. All he could see was danger.

The outcry stopped in an instant. It was replaced by silence so complete that the air suddenly felt heavy, as if a violent thunderstorm was about to break.

With dread in his heart, he turned to face the pavilion. Around him, every man was falling to his knees. The crowd, which had seemed so close to frenzy, was still.

He saw why, and his heart froze.

Tewodros stood in front of his pavilion. He looked just as Stern remembered him. As ever, he was dressed simply in the same white shamma as the lowliest of his men. He was barefoot and wore no gold or jewellery. He did not need to. For his eyes were black and full of fire, and they lit his face better than any precious stone ever could.

‘What do you want?’ Tewodros saw a white-faced farenj in front of him and so spoke in English.

‘I saw Your Majesty’s tent and came hither to offer my humble salutations and respects.’ Stern slithered from the back of his mule. To his relief, his legs did not fold beneath him as he hit the ground. As soon as he found his footing, he bowed low.

‘Where are you going?’

‘I am, with Your Majesty’s sanction, about to proceed to Massorah.’ Stern was proud of his even reply.

‘And why did you come to Abyssinia?’

‘A desire to circulate the word of God amongst Your Majesty’s subjects prompted the enterprise.’ Stern heaved down as deep a breath as he could manage. He felt his gut spasm and shifted his weight, clenching his buttocks tight lest they let loose the torrent of terror.

‘Can you make cannons?’

For the first time since Tewodros had strode out of the tent, Stern did not know what to say. It was an odd question at the best of times, and he was not prepared for it. ‘No, Your Majesty.’ He tried to smile, but his mouth would not respond properly.

‘You lie!’ The two words were bellowed.

Stern took half a pace away from the mad king standing in front of him. He realised that Tewodros was as drunk as his commanders.

‘Where are you from?’ Tewodros roared the question at Negusee. Stern’s servants were lying a yard apart behind their temporary master, their faces turned to the dirt in front of them. ‘You,’ he jabbed a finger towards Negusee, ‘are you the servant of this white man?’

‘No, Your Majesty. I am from Tigray. I am in the employ of Consul Cameron and only accompany this man down to Adowa, whither I am bound to see my family.’ Negusee spoke without lifting his head.

‘You vile carcass! You base dog! You rotten donkey! You dare to bandy words with your king.’ Tewodros’s rage was immediate. He could not keep still and hopped from foot to foot, arms gesticulating wildly. ‘Down with the villain and bemouti, beat him till there is not a breath in his worthless carcass!’

Stern could do nothing but stand and stare as one of Tewodros’s guards stepped forward, a club the length of a man’s leg in his hands. He was still staring when the club was pulled back then smashed down violently onto Negusee’s head.

‘Your Majesty.’ Stern tried to intervene, but the words came out in nothing more than the quietest whisper. Events were happening too fast. It was as if what he was seeing was somehow not real; a night terror come to life. Never before had he felt such complete dread. It consumed him, paralysing his body.

Tewodros’s guard battered Negusee without pause. The servant was helpless, but still he tried to defend himself. He lifted an arm, attempting to ward off a blow. The stick smacked into it, the bone shattering with a loud snap. Negusee screamed then, pain and fear released. Blow followed blow. After a dozen, he no longer moved. Still the stick came for him. Blood flew, the wooden shaft of the stick running thick with it, slathering the hands of the guard.

Stern watched on, frozen with fear, as Negusee was beaten to a pulp, his head shattered and his limbs flattened. The only sound was the thump of the heavy stick into flesh and the grunts and gasps of the guard who wielded it without thought of mercy.

‘There’s another man yonder!’ Tewodros was not done. He stood behind his guard, face twisted with relish as he watched Negusee die, the front of his white shamma speckled with bright red blood. Now he pointed at Uttam, who just lay there, shaking in abject terror as his fellow servant was beaten to death in front of his eyes. ‘Kill him also!’ Tewodros shrieked the words, his rage heightened by the blood spilled at his command.

Uttam looked up in horror as he saw his fate approach. He was given time to do nothing more before the bloodstained stick came for him. The first blow smacked into his head, shattering his skull. The battering started again. It was slower this time, the guard tiring of his gruesome task. Yet still the club did its bloody work.

Tewodros turned away, drawing a pistol from beneath his shamma. He aimed it at Stern. ‘You insult me!’

Stern opened his mouth. No sound came out. He could do nothing but stand there, terror freezing his very soul.

‘Knock him down!’ Tewodros screamed. ‘Brain him! Kill him!’

Stern went ice cold. At the last, he felt his bladder give way, a sudden warm rush of hot piss soaking into the front of his trousers.

Then the guard came for him.

Stern came back to life. He did not want to. With life came pain. It consumed him, the white-hot torture like nothing he had ever experienced. He did not know how he still lived. There were few memories of the beating he had received. God had been merciful and had taken away his consciousness to spare him the horror. Now he awoke to agony and to the iron touch of shackles clasped around his ankles and wrists. He knew he was a prisoner of the Mad King, one of the hundreds of souls incarcerated for a hundred different unnamed crimes.

He cried out then, his body racked by great heaves and shudders as terror engulfed him. He raged into the darkness, fear and pain mixed into an intoxicating cocktail that took away every part of his true self. He did not know for how long he screamed, but it went on until he was utterly spent, his cries losing their power until they were little more than a pathetic whimper. Only then did he try to move, but the chains around his wrists and ankles were too heavy, and he could do nothing more than writhe on the ground.

He lay still. A great feeling of nothingness overwhelmed him. He was utterly powerless. He was beaten. He was broken. He was alone.

‘Fear not, for I am with thee,’ he whispered into the darkness, seeking his God. ‘Be not dismayed, for I am thy God. I will strengthen thee, yea, I will help thee; yes, I will uphold thee with the right hand of my righteousness.’

The words echoed in the gloom. Stern fell silent. He was a prisoner of the Mad King, but he would never be alone.

For his God was with him.

London, January 1868

The darkness wrapped itself around the streets of Whitechapel like the remorseless fingers of a murderer tightening around a victim’s throat. The particular was bad that night, the fog thick, choking, cold. It had been the same all week, the lifeless, breathless air filled with the cloying tendrils of smog both day and night, the dense haze making it impossible to see more than a couple of yards ahead. For some, that was a good thing. There was little beauty on display in the narrow, forgotten streets of the East End, and many would say the filth and squalor was at its best when hidden from sight. But it was not the lack of aesthetic qualities that made some favour a fog-filled night such as this. For in the particular, anything could happen. And it frequently did.

‘Where is he?’ The voice was overly loud, as if a deliberate attempt to hide the fear of its owner was being made.

‘He will be here.’ The answer came immediately. It was hissed, the sound pitched low. ‘And keep your bloody voice down.’ Only the foolish brought attention to themselves in such a place as this. Especially when their accent betrayed their status as clearly as any open display of wealth.

‘I said that slumming was a terrible idea,’ the first voice replied, although this time the advice had been heeded, the words spoken with reduced volume.

‘Then you should have stayed at home.’ There was little pity in the second voice.

‘Maybe I should.’

‘Then go.’

‘Good grief. Not on my own!’

‘In that case, shut up.’

‘You are being cruel, Charles.’

‘And you, my dear Bertie, are worrying about nothing.’ Charles Worthington, son of a lord and owner of the largest collection of silk handkerchiefs in all of London, spoke quickly and smoothly.

‘How on earth can I be worrying about nothing? I thought the whole point of this exercise was to go somewhere that is absolutely not safe. Is this place not dangerous?’ Albert Moncrieff, known to all as Bertie, no longer attempted to hide his concern. He came from new money, his grandfather a small-town businessman from the fringes of London who had made his fortune investing in canals. That one fact had dominated his life, from his first day at prep school to this evening in the gloomy streets of the East End.

‘The point was to have some fun.’ A third voice entered the discussion. ‘And we cannot have even an iota of that if you insist on whining, old man.’

‘I am not whining, Johnny. I’d just feel better if this man of yours could damn well be on time.’ Bertie lacked the silver-spoon swagger of his two companions and his trembling tone belied his concern.

‘He will be here, I assure you.’

‘How can you be so sure?’

‘Because he won’t get paid if he does not appear.’ John Arbuthnot Brown was the son of a politician. He was certain of himself and his place in the world, and he showed that constant confidence in the snap of his tone and the terseness of his words. ‘He is a businessman, after all. I very much doubt his enterprise will survive if he does not take care of his guests. My cousin was here just last week, and he has yet to stop talking of the larks he and his gang had. He said that it was the best night of his life, a veritable trip into Babel, and I for one fully intend to experience that for myself. Besides, the man we await lives on his reputation, and that reputation will count for naught if he allows us to be molested or interfered with in any way.’

The three men had dressed for the occasion, and their long plain black overcoats did a fair job of not drawing attention as they waited, just as instructed, at the corner of Great Prescot Street and Mansell Street, a short stroll from the omnibus station at Aldgate. Despite the hour, the fog and the darkness, they were surrounded by a great crowd. In Whitechapel, life was conducted on the streets. Those streets teemed with people both young and old; men, women and children mixing together as they spent another night doing all they could to avoid returning to the overcrowded tenements where they would pass a miserable, cold night before starting another merciless day attempting to survive.

Many of the barrows and stalls that catered to the throng had closed for the day, but those that served the night-time crowd were still very much in evidence. A baked-potato man, a great cloud of steam billowing from the chimney built into the lid of his tin oven, was busy on the other side of the street. Two young girls, neither much more than ten years old, were selling matches from tin trays held against their small tummies by knotted string worn around their necks. Both shouted for attention, their high-pitched voices competing with one another for the punters passing by. Next to the girls, a glove seller, a woman well wrapped in heavy woollen shawls, her face barely visible between a thick muffler and a trilby hat pulled low, was doing a brisk trade, with plenty of customers for her wares. To her side, a man sat forlornly on a stool next to a great tin bath filled with ice. He was roundly ignored by the crowd, who were already chilled to the bone. A man selling pea soup was doing a much better trade, his bucket already nearly emptied and ready to be refilled from the local chop house.

‘I am cold and hungry.’ Bertie broke the silence. He shuffled from foot to foot as he spoke.

‘Do shut up, old man.’ It was John who answered, his tone betraying nothing but annoyance. ‘And try to stand still.’

‘I am quite certain that someone has defecated near here.’ Bertie ignored the advice. He sniffed to

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...