- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

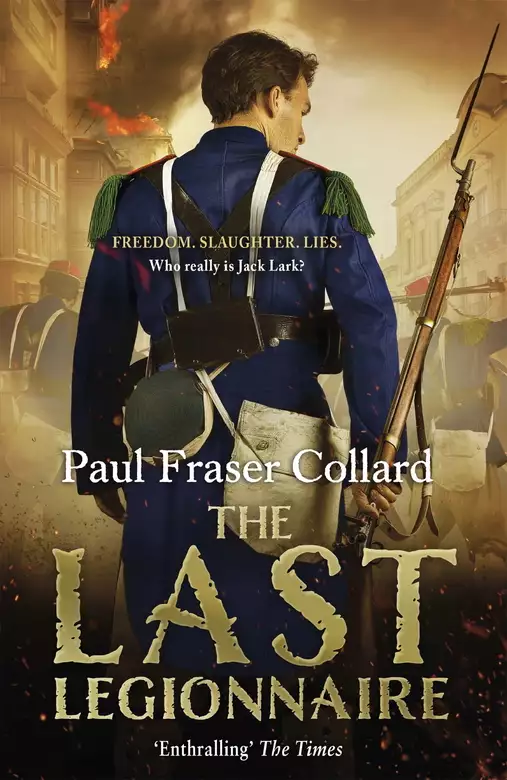

Paul Fraser Collard's Jack Lark series continues with The Last Legionnaire, which sees Jack marching into the biggest battle Europe has ever known. Fans of Bernard Cornwell hero Richard Sharpe and Simon Scarrow's Britannia will delight in the fast pace and vivid storytelling of Jack's fifth adventure. 'Enthralling' - The Times

Jack Lark has come a long way since his days as a gin palace pot boy. But can he surrender the thrill of freedom to return home?

London, 1859. After years fighting for Queen and country, Jack walks back into his mother's East End gin palace a changed man. Haunted by the horrors of battle, and the constant fight for survival, he longs for a life to call his own. But the city - and its people - has altered almost beyond recognition, and Jack cannot see a place for himself there.

A desperate moment leaves him indebted to the Devil - intelligence officer Major John Ballard, who once again leads Jack to the battlefield with a task he can't refuse. He tried to deny being a soldier once. He won't make the same mistake again.

Europe is about to go to war. Jack Lark will march with them.

(P)2017 Headline Digital

Release date: April 7, 2016

Publisher: Headline

Print pages: 376

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Last Legionnaire

Paul Fraser Collard

The alleyway stank to high heaven. The remains of a dead dog lay beside the officer’s boots, its rotten corpse bloated and stinking. The stench rose up, the fetid miasma catching at the back of his throat, so he spat, scouring the bitterness from his mouth. The stink of the rookeries had not changed in the years he had been away.

He pulled his greatcoat a little tighter around him, then stepped over the matted fur of the dead dog. The streets far from London’s more fashionable areas were familiar to him, despite the fact that he had not been there for nigh on a decade. The mean back-to-back houses of the slums were still pressed cheek by jowl. The same angry shouts of frustration came from the souls incarcerated within, the screams of their babies stirring memories of the place he had left so many years before.

He had long thought about this moment, the dream of his return sustaining him during his first weeks and months in the Queen’s army. He had been forced to leave this place, a brutal fight denying him the right to live under his mother’s roof. The army had taken him in. It had clothed him and fed him. It had trained him to be a redcoat, a killer of the Queen’s many enemies, and it had given him a home when no one else would. Now he was back wearing the uniform of a captain in the 3rd Regiment of Foot. He was no longer the unwanted son, the boy who just wanted to be man. He was an officer, a man of station and importance. Or at least he was dressed as one.

The officer pressed on. He stuck to the alleyways; the narrow spaces that ran behind the tight rows of squalid housing. The main streets would be busy this close to dinnertime. The match sellers and the patterers would be working the crowd, and the costermongers would be looking to clear away the last of the day’s stock from their barrows before they turned in for the night. The officer did not want the attention that he knew his presence would attract. The eager men, women and children who worked the streets of Whitechapel were certain to be keen to see him part with the shillings in his pockets, either willingly or not.

A young boy came rushing in the opposite direction. He was moving fast, his small feet sure and steady, his arms pumping hard as he ran. He only spotted the tall figure in the greatcoat at the last moment, and he skidded to a halt, his eyes darting this way and that as he tried to find a way past.

‘’Scuse me, mister.’

The officer smiled. He had spotted the boy’s clenched fist, and could smell the aroma of the small meat pie even over the pungent stink of the alley. He fished in a pocket to pull out a coin before offering it up like a conjuror seeking to amaze his audience.

‘You want to earn a sixpence, lad?’

The boy’s face creased into a scowl. He could not have been more than ten years old, but he knew enough to be wary of gentlemen who hid in the shadows and flashed their money at small boys.

The officer saw the boy’s expression. He wanted to laugh, but he kept his humour contained, just as he hid all his emotions away. ‘Stand easy, lad. I’ve got a question, that’s all.’

The look of suspicion did not change.

‘The Counting House, do you know it?’

The boy bit his lip. His eyes were fixed on the sixpence.

The officer lifted the coin higher, further from the boy’s reach. ‘Do you know it?’ he repeated.

The boy nodded, his scowl deepening as he realised he could not snatch the coin and escape.

‘Who runs the place these days?’

‘Old Maggie, of course.’ The boy’s answer was quick, his scorn at such a foolish question obvious.

‘Maggie Lampkin?’ The officer lowered the coin a fraction.

‘Course. It has always been her place.’

‘What about her old man? Is he still there?’

‘You said one question.’ The boy’s eyes narrowed. ‘Two questions cost a shilling.’

The officer could not help but smile. ‘For a shilling, I’d want you to take me there.’

The boy flashed a smile of his own. He had never spent a single day at school, but he knew how to tally a man’s worth. ‘You lost, mister?’

‘No.’

‘Then why’d you want me to walk you?’

‘Maybe I just want the company.’ The officer watched the boy closely. It did not feel so long ago that it had been him filching meat pies from old Bartholomew’s barrow.

‘I ain’t that kind of boy, mister.’

The officer’s hand moved quicker than the boy’s eyes could track. It cuffed him around the ear, the blow short and sharp. ‘Shut your filthy muzzle.’

The boy lifted his chin to show the blow had not hurt. ‘So what’s your name, mister?’

The officer snorted. ‘The going rate appears to be sixpence for a question, a shilling for two.’

The boy laughed. The sound came quick and easy. ‘Fair enough.’ This time it was his hand that moved fast, the purloined pie slipped into a pocket. ‘I’ll take you to the ginny.’ He looked the officer in the eye. ‘For that shilling of yours.’

The officer flicked the sixpence at his new guide. ‘I don’t want any trouble. You get me there nice and quiet and I might be inclined to be generous.’

The boy snatched the coin out of the air, making it disappear within the span of a single heartbeat. He contemplated the officer, his eyes narrowing as he assessed the options.

The officer saw it all. He raised a hand and pointed down the alley. ‘Now walk your chalk. I’ll follow you. And if you run, I’ll come after you.’

‘I won’t peg it, mister.’ The boy’s fleeting smile hid the notion that he had been thinking of doing exactly that. ‘I want your other sixpence.’

The officer did not respond to the choice reply. He waited for the boy to do as he had been instructed.

The boy took one last look at the scarred face and the hard grey eyes. The officer did not appear to be the sort to take kindly to being disobeyed, so he turned and set off down the alleyway.

The officer followed. He did not need the boy to show him the way, but he had not lied when he had said he wanted the company. He knew the paths he had to follow, but not who waited around the next corner. The boy would. The officer did not fear footpads; he had killed too many men for that. But he did not want to return here as a killer. There would be time enough to reveal his bitter talents, the skills that had kept him alive on the battlefields of the Crimea, Persia and India. For now, he wanted nothing more than to find out if he had a place that he could finally call home.

The officer held back as they emerged from the alley. The light was fading, but the three pairs of gas lamps on the wall of the gin palace burned brightly enough to cast a glow for yards in all directions. The blue-tinged light played across the display of gilded rosettes and sconces on the palace’s garish facade, the gilt burners a beacon that summoned the thirsty congregation to their worship.

He stared at the great plate-glass window decorated with the image of a giant sun. He remembered the day the glass had arrived, the crowd that had gathered as the ancient windows were hacked out and replaced by the single glittering sheet. He savoured the memory, the glory of that day shimmering through the years. He had been proud then. Proud of his status, his position in the dark society of the rookery assured by his mother’s ownership of the one place that offered the locals a respite from the never-ending drudgery of their sorry existence.

Yet that pride had not been his to savour. It had faded fast, quicker even than the purple and yellow bruises that marked his flesh as his mother’s old man demonstrated just who owned what. He had not felt the same pride again until the day he had first pulled the heavy woollen red coat of a soldier on to his shoulders.

‘Come on, mister. What you waiting for?’ The boy turned to shake his head at the rum cove with the ready supply of tin. ‘There it is. I saw you right, didn’t I just.’ The palm was held out. ‘I reckon that’s sixpence you owe me.’

The officer dipped a hand into the pocket of his greatcoat, then flipped out another coin. ‘Easy money.’

This coin too disappeared quickly. ‘You want me to wait to get you back to a cab?’

The officer smiled. ‘No.’

‘Staying for a bit, are you?’ The boy smirked. He knew why men of a respectable kind would go out of their way to visit a back-street gin palace.

‘Perhaps.’ The officer knew what raised the boy’s smile. ‘Does Mary still work there?’

The smile was gone. The scowl that replaced it was fierce. ‘She works there, but not like that. And she’s too good for the likes of you.’

The officer was surprised by the strength of the reaction. He had once believed he had loved this girl called Mary. She had been a rare beauty, the kind that men would pay dearly for the right to be in her bed for an hour or two. The officer had never been granted such a delight, but the notion still sparked an itch in his groin that even nine years away had been unable to extinguish.

He looked at the boy carefully. ‘What does she do now?’

The chin lifted. ‘She helps Maggie run the place. Looks after it herself at times too.’

The officer took the news in. He wondered what else had changed in the years he had been away.

The boy sniffed, then wiped his nose on the cuff of his grey flannel shirt. ‘You want anything else, mister? I know a place that might suit you better. It ain’t far.’

‘No.’ The officer shivered. He felt the first fluttering of nervousness deep in his gut. It was like the moment before battle, the quiet time when the bravado stopped and each man was left alone with his fear. Angry at his reaction, he hid his emotions and stepped forward, the boy forgotten, making for the door that announced entry to the Counting House, the words etched deep into a plate of ground glass.

The air inside was thick with pipe smoke, and the stench of overripe bodies caught in his throat. The smell had not changed. The stink of piss and gin was just as he remembered.

His boots scuffed the sawdust spread on the floor. It needed changing; the scarred and stained floorboards were visible in wide patches. He ran his eyes around the room, the memories surging through him in a great unstoppable wave.

The early-evening crowd filled the place, men, women and children standing in docile lines as they waited for their turn at the great slab of mahogany that stretched across the far side of the room. He knew no one there, but the faces were just as he remembered, the same sea of sad, careworn expressions, passive in the expectation of relief.

He glanced behind the mahogany bar, his eyes roving over the complex arrangement of spiral brass pipes that led from a series of barrels lining the wall to a line of spirit taps that bore the names of the various brews. ‘The Out and Out’, ‘The No Mistake’, ‘The Bairn’s Favourite’, ‘The True Spirit’, ‘The Sit-Me-Down’; the bold names, and their even bolder claims, made him smile. He remembered the great vat in the yard behind the palace where the gin was watered down before it was fed into the barrels, the brew the same no matter what fanciful name it took.

‘Billy! Where the devil have you been?’ The question was snapped out, the voice shrill and carrying easily over the chatter of the palace’s patrons.

The officer started. He looked for the owner of the voice, a cold surge of nervous anticipation churning in his gut.

‘Come here, you little scamp. I should tan your bleeding backside. You’re late like bloody always.’

The officer was buffeted as the boy who had guided him to the palace pushed past.

‘I’m here now, Maggie. I’ve been working.’

The officer noticed the approving smiles on the faces of the crowd, the boy’s bold retort earning their approval. More than one hand reached out to ruffle his hair as he worked a seam, his passage to the bar made easy as men and women stepped out of his way.

‘My eye, working, is it? You should’ve been working here, you little tyke.’

The officer scanned across the heads of the crowd, searching for the woman who had called to the boy, and whose voice had sent a shiver running down his spine.

‘I’m here now, Maggie, so don’t you fret; at your age it could be the death of you.’ The boy beamed at the crowd’s reaction, nodding at the smiles and winking at one of the girls in red stockings sitting on a stool near the fireplace. He stuck his thumbs under the lapels of his worn worsted jacket, his narrow chest puffed out. ‘Where d’you want me?’

‘There’s piss in the parlour. Mop it up, there’s a darling.’

The crowd chuckled. The palace’s customers formed a willing audience to the show put on by the cocky lad and the loud bawd behind the counter. It was what they came for almost as much as the thin gin they bought by the pennyworth, the bright lights and the spectacle a relief from the dour greyness of their lives.

The officer did not join in. He hung back, his greatcoat wrapped tight around him, the fabulous scarlet of his uniform covered and his tall black shako pulled low over his eyes. He kept his face hidden. His own mother would not recognise him.

‘Good evening, sir!’ The woman the boy had addressed as Maggie spied the stranger’s presence in her place. He was a head taller than most in the room and he stood out like a fox in a henhouse. ‘There’s a good seat in the parlour for a fine gentleman like you. No need to wait with this lot of sorry sods.’

The officer locked his eyes on the owner of the loud, hectoring voice as the crowd laughed off her insult. She was barely tall enough to see over the bar. The hair piled high on her head might once have been a fiery red, but now there was more grey than ginger. It sat like a pale and ancient cat above a florid jowly face with lips rouged to a bright red.

‘Make way for the gentleman, you lazy buggers,’ Maggie ordered. There were stares, and a fair few scowls, from the locals, who were immediately suspicious of a stranger. ‘Make way, I say.’

The officer moved forward, towards the bar.

‘The parlour, my love, it’s just behind you on the right. That’s the place for a fine gentleman like you. Young Billy here will come to see to you when you’re settled.’

The officer paid the direction no heed. He moved closer, studying the woman’s face. Unlike the palace, she had changed. Flesh and spirit had been eroded in a way carved wood and glass could never be. Yet the light in the puffy grey eyes was unaltered by the passage of time.

‘Oh, you’re a thirsty fellow, are you?’ She shook her head, but still found a smile for the man who would pay at least triple the going rate for his drink. ‘What’ll it be then, sir? A touch of the good stuff for a fine gentleman like you, I shouldn’t wonder? Why, I think I’ve got a bottle or two with your name on it down here. Better stuff than I serve the likes of these miserable bastards!’

The crowd reacted to their cue with mocking groans and hoots of disapproval.

‘Hush, you lot. You knows your place!’ The woman laughed off their grunts and growls, her eyes coming to rest on the tall officer who now stood directly in front of the proprietor of the Counting House, the finest gin palace this side of Petticoat Lane.

‘What’ll it be then, my love?’

The officer could see the suspicion in the woman’s eyes. The slight flicker of fear as the stranger stayed silent.

The room fell quiet as the question hung heavy without a reply.

The officer pulled off his shako, his hand instinctively running through his close-cropped hair. He looked at the woman, whose eyes widened as she finally realised who had come back to her palace.

He offered a thin smile. ‘Evening, Ma.’

The palace’s owner stared back. Her mouth opened, but no sound came out.

Jack Lark let the flaps of his army greatcoat fall open. The scarlet officer’s coatee was bright amidst the drab greys and browns around him. He had come a long way in the years he had been away. But now he was home.

‘Where did you get that bigger one?’

Maggie’s hand traced the thick scar on her son’s left cheek. They sat together at one end of the table in the palace’s back room, a space usually reserved for gambling, or for dealing with private business that needed to be conducted away from the prying eyes of the customers. Jack’s greatcoat hung from a peg on the wall and his scarlet officer’s coatee was draped across the back of his chair. He had removed his sword, but his holstered revolver stayed on his hip, the familiar weight reassuring.

‘Delhi.’

‘Delhi! Where the hell is that when it’s at home?’

‘It’s in India, Ma.’ The answer was given softly. Jack pulled away from her touch.

His mother’s hand dropped. ‘Was there fighting there, then?’

Jack shivered. He had been with the British soldiers when they first forced their way on to the ridge that overlooked the city of Delhi in the weeks after the native soldiers had mutinied against their white masters. He had still been there months later when the British finally launched an assault on the great city that had become the heart of the rebellion.

His mother sat back, her hands retreating to her lap. ‘You look older.’

‘So do you.’ Jack tasted a moment’s anger. He had not known what to expect when he finally completed the long journey that had started at a graveside outside Delhi all those months before, but now that the moment had finally arrived, he felt surprisingly little.

‘It ain’t been easy.’

There was awkwardness between them, the years a chasm that was not easily crossed.

‘What about Lampkin?’ It was hard not to sneer as he named his former master. Jack had lived under the man’s sufferance, paying his board and lodging in work and in beatings. Until the day when he had fought back.

His mother snorted. ‘He’s a dead’un. He passed a few months after you left.’ She was derisive. ‘He was never the same after you did him over. Of course, the stupid bugger wouldn’t admit it. He got in a fight with some fellows from down by the river. I don’t know what it was about. He died.’

Jack remembered the fight that had led to his banishment. He remembered the young man who had fallen into Lampkin’s clutches, but he could not recall the lad’s name. Jack had arrived in time to attempt a rescue, but the fight had not been over the fate of a stranger. It had been coming ever since the day Lampkin arrived to claim the palace and its proprietor as his own.

‘He never recovered. You hurt him bad that day, Jack.’

‘He drew a knife.’

‘And you beat him half to death for it.’

Jack felt little as he absorbed the news. Death had been his constant companion for years. He had seen so many friends die; lost so many of those that he had foolishly allowed to come close. Against that, the fate of his former master meant nothing. ‘You chose him over me.’

‘I couldn’t turf him out. Not after all he did for us.’

‘For you.’

‘For us. We wouldn’t have lasted a month after your fool of a father fucked off.’

‘You still chose him over me at the end.’

‘I had to.’ Her reply was cold. ‘I had no choice.’ The words were bitter. She reached out to take his hand.

Jack was watching his mother closely. He had come to understand her better over the years. He had been almost a grown man when he had fought Lampkin. In the aftermath of the fight, he had made his mother choose between them and he had been the one discarded. Yet the life he had lived in the years he had been away had given him a different perspective to the one he had had that day. He knew he would not have stayed even if she had chosen him. He would have moved on, leaving his mother to face whatever fate had in store for her. Lampkin had been her choice. He was a vicious, bullying bastard, but he was her bastard and he would be there when her only son had long departed. Jack had forced her to choose, but he now knew that there had only been one option she could have taken.

‘I know, and I survived.’ He felt uncomfortable under her touch. Her hand was cold, the skin dry and chafed. It was the hand of a woman who worked hard for her living.

‘And look at you! You came good.’

‘This isn’t real.’ He had decided on total honesty. He had left his lies back in India. ‘I stole it.’

For the first time, his mother smiled. ‘You ain’t a Rupert?’

‘No. Not a real one. I have been, though.’ Jack could not match her smile. He had been a British officer for a time. Or at least he had pretended to be one. He had stolen a rank far above his own, fighting in the Crimea as a charlatan captain, commanding a company of redcoats in the battle at the Alma river in the place of an officer who had died in the peace of the Kent countryside. ‘I was even a general once.’

‘A general!’

‘I served an Indian maharajah. I saved his son. He gave me the title as a reward.’ Jack could scarcely remember the months he had spent in the maharajah’s court. It was if the memory belonged to someone else.

‘What about all those Indian princesses? If you was a general, they must have swooned at the very sight of you!’ His mother tried to tease him.

Jack thought about the one Indian princess he had known. ‘No, they didn’t swoon, Ma.’

‘There must have been a girl or two out there.’

‘One or two.’

‘No one special?’

Jack found it hard to swallow. ‘No, Ma, no one special.’ He gave the lie badly. He felt the memories stir, the first tugs on the chains that kept them shackled in the shadows. He forced them away and steered the conversation back to his mother. ‘No one to replace Lampkin?’

His mother’s laugh was short. ‘I’m an old woman, Jack.’

‘An old woman with a palace.’

‘Oh, men want that all right. They just don’t want me.’

Jack saw a shadow flicker across her face.

‘You’ve been a long way from home.’ His mother looked down, her eyes following one of the many cracks in the table.

‘I’m back now.’ He could see that she was struggling to take it all in. He had a feeling that his words meant little; that his tale was barely registering. She looked up to stare at his face, searching it for something.

‘So if you ain’t an officer, what are you?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘A runner?’

‘No, I have my papers.’ Jack thought of Ballard, the intelligence officer he had served under during the campaign against the shah. His reward had been a set of discharge papers that had given him back his own name. He had fought at Delhi as himself, his experience of war the only qualification he had needed in the turmoil that had gripped the country in the months after the mutiny.

‘So are you staying? Are you back for good?’

‘I reckon.’ Jack was uncomfortable. His plan had been to return to the place where he had been brought up. He had not thought any further ahead than that. He had been an impostor and a thief, but now he had turned his back on all that. He no longer strove to be someone he was not, such ambition washed away by an ocean of blood. He didn’t need to prove he was better than the fools and wastrels allowed to become officers simply by virtue of their birth. He craved something far simpler yet infinitely harder to find. He wanted a place to call home.

‘You can stay if you like?’ The offer was made with hesitation.

‘I’d like that.’ Jack felt the tremble in his mother’s hands. He realised she wanted him back but had feared he would not stay. ‘So who helps you here?’

His mother smiled. She had the answer she wanted. ‘Mary. She had a boy and I took her in. She works hard, bless her, I couldn’t manage without her. Since you left she’s become like a daughter to me. Now her boy helps out too. Did what you used to do. You met him tonight.’

It was Jack’s turn to grin. The lad who had escorted him to the palace was Mary’s son. ‘He’s a fine lad.’

‘He’s like you was. A little shit.’

Jack grunted in acknowledgement of the barb. Yet he did not believe everything his mother had told him. Two women and a boy could not hold on to a gin palace. The rookeries did not work like that. ‘That’s all?’

‘We get by.’

‘What about the father of Mary’s nipper? Where’s he?’

‘God alone knows.’ Jack’s mother did not shirk from the facts. Whores were ten-a-penny in Whitechapel. Mary’s story was hardly uncommon. Maggie offered a tight-lipped smile. ‘You always liked her.’

‘She looked out for me.’ He could not resist the pointed comment. It had been Mary who had comforted him when he was alone, who he had gone to when the beatings were bad.

‘You never did what you were told.’ His mother offered a thin smile at the memory. ‘You were always running off.’

The memory stirred nothing in Jack’s heart. He tried to conjure an image from the past, but he found he could not do it. If he tried too hard to search his memories, he woke the faces of the dead that lived in the darkest recesses of his mind. He could not bear that, so he simply looked down at the table, his eyes roving across its scarred surface.

‘Did the army teach you to obey orders?’

‘For a bit.’ Jack looked up and saw his mother staring at him. He sensed she wanted him to reveal more of his past, but his cold reaction was keeping her at bay. ‘I wanted more than I was allowed.’

Again the tight smile. ‘I ain’t surprised. You always wanted more, even if it meant taking a hiding from my old man. So you became a redcoat and then a thief?’

Jack nodded. He had once thought of it in grander terms: a crusade to be the kind of officer the redcoats deserved, taking him to places he would never have believed possible. But such naive dreams meant nothing in war. ‘I was good at being a soldier.’ He revealed a little of his pride. It was all he had, the satisfaction at what he had become, the skills he had learned in battle the only true thing about him.

‘But you came back here?’

‘I had nowhere else to go.’

‘Last knockings, are we?’ His mother tried to laugh, but the sound died away. She pulled her hand free.

‘I wanted to come.’ His skin tingled, cold now the warmth of her hand was gone.

‘I’m glad. You here to work?’

‘I’ll help you. If you’ll have me.’

For the first time his mother looked unsure. ‘Things are different now. We ain’t had no man here since John passed.’

‘So how did you keep hold of the palace?’ Jack pressed her. His doubts returned. She was not telling him the whole story. An old woman, an ex-whore and a bastard child could not run something as fine as a gin palace by themselves.

‘I pay.’

Jack did not reply at first. He was not surprised. Protection gangs had always been around. Lampkin had had no need of them, for no one in the rookery would have been brave enough to take him on. But without him around, Maggie had been forced to look elsewhere for security. ‘How much?’

‘Half of what we take.’

Jack felt a flicker of temper. That was not protection. It was extortion. He watched his mother closely. She was not ashamed of her decision. She looked up and caught him studying her. She lifted her chin, her eyes narrowing slightly as she waited for him to challenge her.

‘If I stay, you won’t need them any more.’ He kept his tone neutral. He would not pay the bastards. He had brought all the protection he needed. His hand slipped down to touch the hilt of his revolver. He had fought on the walls of Delhi, had defended the British cantonment at Bhundapur and ridden with the Bombay Lights at Khoosh-ab. He had no need of anyone else.

‘They’re bad men, Jack.’

His mother matched his tone. He noticed she did not try to change his mind. He was her son and she did not doubt him. He felt something stir deep within him.

‘They do not know me.’ This time it was Jack who reached out. He took his mother’s hand and held it tight.

‘Maggie!’ Mary’s son, Billy, poked his head around the door. His young face betrayed his fear. ‘Mr Shaw is here. He wants you. He’s clearing the place out.’

Jack’s mother did not move. She stayed still, her eyes locked on to her son’s hand wrapped around her own.

‘Is that him?’ asked Jack.

Maggie nodded.

‘Then I’ll give him the good news myself.’ He patted her hand then got to his feet. He flashed a smile at Billy. ‘You might want to stay back here, lad.’

‘Why?’ The answer was quick. ‘You going to fight Mr Shaw?’ The boy did not look horrified by the idea.

‘No. Least I don’t plan to.’

Young Billy’s face fell. His eyes focused on the holstered revolver on Jack’s hip. ‘Can I take your gun for you?’

‘No.’ Jack saw the boy’s eagerness ‘But if you don’t give me any shit for a week, I’ll teach you how to clean it.’

‘Deal.’ The boy snapped the answer, then his face fell. ‘You might not be alive in a week.’

Jack felt the stirrings of a smile. ‘Is this Mr Shaw that bad?’

The boy bit his lip, then nodded.

‘Well you had better take me to see this monster.’ He gestured at the door. ‘You go first, Ma. We don’t want to alarm Mr Shaw.’

His mother rose to her feet and walked to the door, only pausing when she came level with her son. She looked up, her head tilted back as she studied his face.

‘You know what you are doing, Jack?’

‘No.’ Jack found his smile. ‘I never do.’

His mother grinned back. ‘Well then. Let’s get this done.’ She turned and flapped a han

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...