- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

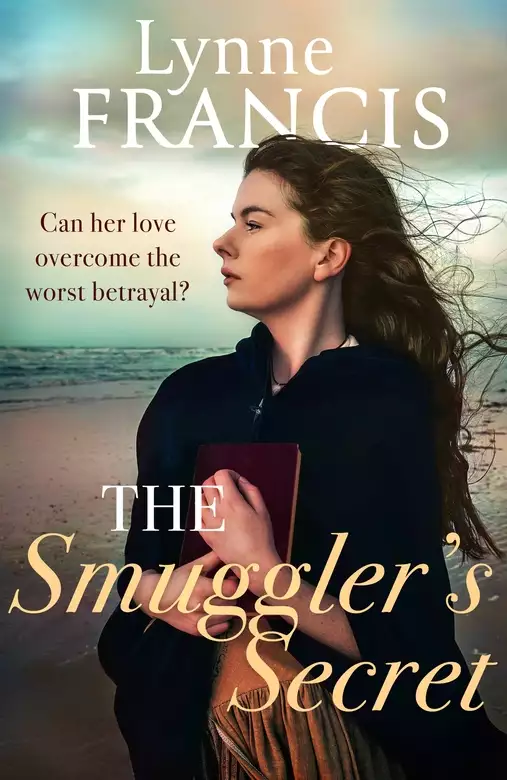

Synopsis

A sweeping saga of friendship, betrayal and finding love in the unlikeliest places.

1813. Haunted by her father's death and tired of watching her mother struggle, Meg Marsh will do anything to keep a roof over her family's head. Even if that means getting involved in a dangerous smuggling operation.

When Meg catches the eye of a dashing gentleman above her station, things start to look up, and she can't help but start dreaming of a life away from the shingle and boats of Castle Bay. Blinded by flattery and coin, Meg can't see the danger on the horizon - and the cost just might be her life.

1913. Carrie Marsh lives a quiet life as a teacher until she falls in with the wealthiest family in Castle Bay and turns the head of the charming eldest son, Oscar.

In an attempt to impress her new friends, she takes them to the secret garden rumoured to be haunted by her murdered ancestor. One outing turns into a carefree summer of pleasure, and the garden becomes a hideaway for Oscar and Carrie.

But when they accidentally stumble upon human bones, Carrie is forced to ask herself whether she really knows Oscar at all - and whether she is doomed to follow in her ancestor's footsteps.Two women, one hundred years apart: will the secrets of the past ever be uncovered?

Praise for Lynne Francis:

'Impressively researched . . . I loved this five star book' Kay Brellend

'An engaging, thoroughly researched tale of youthful naivety and courage in the face of adversity, full of rich detail and imagination. Highly recommended!' RoNA award-winning, bestselling novelist Tania Crosse

'A compelling and captivating historical saga rich in atmosphere, emotion and heart' Goodreads Reviewer

Release date: February 23, 2023

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 90000

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Smuggler's Secret

Lynne Francis

Meg loitered for a few moments outside and watched the moon rising over the water. It was a full moon, a perfect circle, trailing a silver path across the dark, still sea to the distant horizon. The inn would be busy that night, she thought. No wonder Mrs Dunn had need of her. The clear moonlight would put a stop to any smuggling: the French ships involved in the trade would be lying at anchor offshore, inconspicuous among all the other vessels there. Those were waiting for supplies, for crew, for a favourable wind to set them safely on their way to London or across the sea. Some of the sailors would have been given leave earlier that day to row over and beach their small boats on the shingle, tumbling over each other and wetting their feet in their hurry to gain land. The town of Castle Bay was well known for the quantity of taverns within two streets of the shoreline, and the number of pleasure houses set among them.

The smugglers out at sea would be waiting impatiently aboard their boats, hoping that the following night would bring clouds and the opportunity to offload their goods onto the galleys rowed out from Castle Bay. Meg, too, was waiting, although it wasn’t rum or tea that she was expecting.

There was a stranger in the Fountain that night: she’d spotted him at once. He looked out of place. His dark coat was too well cut, his boots were fine leather, and his hands – when he accepted his tankard and handed over his coin – were smooth, the nails neatly trimmed. He was not a man who spent his days toiling to earn a wage.

She watched with amusement as he attempted to engage the other drinkers in conversation. They tolerated him for a few exchanges of pleasantries, then closed ranks against him, turning their backs so he was edged out. After four or five such rebuffs as he circled the room, he returned to the bar, a despondent expression on his face.

Meg served him with more ale. Then, as he lingered, watching the room, she said, ‘You’re not from these parts, I take it?’

‘No, from London,’ the man replied. He seemed wary of offering more information.

‘And what brings you here from the city?’ Meg asked, although she could guess. Others like him had tried their hand at taking a slice of the lucrative smuggled brandy or tea trade, and failed. The Silver Street gang had their distribution networks nicely set up and they weren’t about to be impressed by the promise of riches from London.

‘There’s a gentleman in the city who asked me to find him some goods. The sort he can sell in his shop. Goods for which his customers would pay well.’

‘Oh?’ Meg lifted a tankard from its hook behind the bar and poured the ale for one of the regulars, William Huggett, who had just come in. She handed it over, giving him her best smile, then turned back to her city customer. ‘And what sort of things are you looking for?’

She was unwilling to name the most obvious, wanting him to be the first to do so. It was as well to be cautious. He didn’t look like a revenue man, but they could be wily. One evening, old Frederick Larkin had drunk more than was good for him and, on the way home, had fallen into the trap of believing the weasel words of a revenue man waiting in the shadows, pretending to be the go-between he was expecting. The lucky guess on the revenue man’s part had seen old Mr Larkin lurching happily round to Market Street, to show him the trapdoor from the street that gave access to the kegs of brandy stacked in his cellar. The reward for his foolishness had been a hefty fine, the confiscation of his brandy and a cellar filled with shingle to discourage him from pursuing that line of trade again.

It had happened six months ago but was still fresh in the memory of everyone there, not least Frederick Larkin, who was sitting in the corner nursing the only jar of ale he’d be able to afford all night. Strangers at the Fountain, inside or out, were never good news.

This one, though, looked and sounded too well-bred to be a revenue man. He was gazing into his ale, apparently weighing up whether or not to explain himself. He lifted his head, and Meg saw that his eyes were drawn to the handkerchief she had just tucked into her sleeve. The fabric square was unremarkable – just plain white cotton cambric – but the edging was of the finest lace. Meg hadn’t been able to resist it. She couldn’t afford to keep any of the beautiful fabrics that came over from France – her working clothes were made of coarse wool and undyed linen – but, once she’d measured and cut the lengths of lace, there had been a piece left over. It was too short to sell, but perfectly suited to edging a handkerchief.

‘That’s a fine piece of lace!’ The man reached out and caught Meg’s wrist. ‘Now where would you be finding handiwork like that? From France, at a guess. My master would pay well for such things.’

Meg saw that some in the inn had noticed his action, among them Joseph Huggett. He was William’s son, and without a doubt the most handsome of the regular visitors to the Fountain. She also knew him to have more than a passing interest in her. She disengaged her hand and made a show of lifting down another tankard, then picking up a cloth to polish it.

Speaking quietly, her head slightly turned away, she said, ‘I can find you such things, and more. But we can’t discuss it here. There’s a corn mill called Oakley’s to the north of the town. Walk out beyond the brewery and the timber yard, past a row of fine houses, and you will see it before you, standing to this side of Downs Castle. I suppose it’s less than a mile from this spot. I’ll meet you there tomorrow morning at ten o’clock. You can judge for yourself the quality of the lace and silk I have. But now I can’t be seen to be speaking to you any longer. You’d do well to drink up and get back to your lodging. And watch your back.’

Meg turned back to serve newly arrived customers. When she turned back, the man had gone, his presence betrayed only by a trace of froth in the bottom of his tankard.

‘Who was that?’ Joseph was standing before her, his own tankard all but empty.

Meg shrugged. ‘Someone down from London. Asking questions about houses for rent in Golden Street. I told him he needed to talk to the notary, not the girl who works behind the bar of an inn.’

She didn’t like lying to Joseph, and his expression suggested that he didn’t entirely believe her, but she was saved from further discussion by the arrival of a group of fishermen, their boats newly landed. They all arrived at the bar at the same time, bringing with them a strong whiff of fish and a desperate thirst.

She hoped no one could see how flustered she felt after making the bold arrangement with the stranger. Her heart was beating fast even as she laughed and joked with the men, while her thoughts were entirely taken up by the idea that this could be her chance to assure her family’s future. As she walked home later that night, she glanced up at the star-filled sky, and imagined her father watching over her. She hoped he approved.

The next morning Meg was at the meeting place near the corn mill well before the appointed hour. She gazed out over the broad sweep of the bay while she waited. The water looked almost green where the horizon met the blue of the sky, and the sun sparkled on the calm sea. The town of Castle Bay sat at the centre of the shingle bay, with three Tudor castles spaced along its stretch. Broad Castle, named after its builder William Broad, sat at the town’s southerly edge, with Hawksdown Castle a couple of miles beyond it. France was visible when the weather was favourable, close enough for Henry VIII to have ordered the building of the castles to protect the coast more than two hundred and fifty years earlier. Downs Castle, now falling into disrepair, was out to the north of the town, along a little-used path. Few passed that way other than those with business at Oakley’s mill.

Meg had folded her lace and fabrics neatly into the bottom of her basket, covering them with a faded cloth. It was her first venture in undertaking a little private business, in a town where the smugglers operated as a band, keeping each other appraised of their movements. She was wary of being suspected of operating outside the tight-knit group. In addition, if the revenue men should happen to be about she would need to appear above suspicion. And her mother would be furious if she knew what her daughter was up to: she believed she had gone out to buy flour from the mill. Her venture today was risky – a step into the unknown, which could either be the making of her or result in the loss of everything.

She saw the man she was waiting for toiling along the beach path and smiled to herself. She’d enjoyed the walk on such a bright, crisp morning, the sun barely warm enough to melt the frost on the grass. It was clear this man was more used to walking the streets of a city than the sort of rough track that lay beyond the town.

‘I hope this is going to be worth the effort.’ He was not in a good mood. ‘I must be back in London this evening and I plan to take the next stage coach out of this place.’

Meg didn’t waste time in placating him. Instead, she pulled back the cloth hiding the contents of her basket. His eyes brightened as he took in what he saw, and he was quick to lift out the differing widths of lace, the brightly coloured silks, plain and printed, and the fine muslin.

‘I think my master will be happy to take whatever you can get of this quality,’ he said. ‘Provided the price is right, of course.’

He regarded her with eyes that carried no expression of interest in her. He would drive a hard bargain, Meg thought. But, then, she had the upper hand. She knew where to source these wares and he didn’t. If he wanted her to supply him, he would have to pay her price.

The deal was surprisingly easily done. Meg reflected on it as she walked back to town, having taken the precaution of stopping at the mill for a small sack of flour. Her new customer would have been back in Castle Bay well before her, bent on getting the midday stage.

She had given him a sample of lace and a piece of silk, which he had tucked inside his jacket, and he had handed over a bag of coin to pay for the promised goods. They had shaken on it and exchanged names – Ralph Carter for Meg Marsh – but he had no other surety. She had said she would meet the carriage he sent to South Street each Saturday, and that his goods would return on it. Her word was her bond, but in any case, he would know it was easy to find her in the town. She would prove to be good at this business, she thought. Once their trade was established, once he had customers eager for what she could provide, she would raise the prices. There’d be money enough to keep the Silver Street gang sweet, and she’d be able to buy more from Philippe, the French smuggler.

The bag of flour Meg carried was quite a burden but she was young and strong. The sunshine and the business had raised her spirits, and she bestowed smiles and greetings on all those she passed. More than one continued on their way reflecting on what an attractive young woman Meg Marsh had grown up to be, her long dark hair escaping from her cap, her brown eyes merry.

Back in Prospect Street, the bell above the door jangled as Meg stepped into the narrow hallway. The house was larger than it first appeared: the bow-fronted window on the ground floor housed her mother’s shop, with the bedrooms on the floor above and in the attic. The family lived mostly in the basement kitchen at the back of the property and there was a cellar and a yard with a gate, which led into a discreet alley running off Beach Street. Although every house had a different appearance, the best-kept secret of Prospect Street was that all the cellars interconnected. Goods could be offloaded on the beach and, within five minutes, secreted in the cellars of the first house in the street before being moved by willing hands to emerge onto Middle Street a night or so later.

The red-tiled roofs, at different heights, also hid something from the unsuspecting revenue men. With them in hot pursuit, a man could slip into an alley, through an open gate into the yard of one of the houses, make his way from there up to the top floor and out through a window onto the roof. A narrow, hidden walkway at that level allowed him to continue to Middle Street, where he could climb down and settle himself in a corner of one of the inns, where everyone would swear he had been drinking all night.

Meg was about to make her way along the passage and down into the kitchen when her mother called, ‘Is that you, daughter? Can you mind the shop for me? I must step out to see Mrs Millgate.’

Meg turned back and entered the shop, in reality little more than a display table in the window, and another table behind which Mrs Marsh stood and served her customers. Since the death of her husband, it had been hard for Meg’s mother to continue the business. Mr Marsh had been the baker, getting up in the middle of the night to prepare and bake the bread. Mrs Marsh had made currant buns and scones – nothing too elaborate, for even when the smuggling profits were good there was not much call in that area for cakes and fancies.

Today two or three currant buns – whirls of baked yeasty dough studded with dried fruit – sat in the window. Meg suspected they were several days old. ‘I’ve brought the flour, Ma,’ she said. ‘Shall I bake something for the shop this afternoon?’

‘That would be nice.’ Mrs Marsh was vague, throwing her faded wool shawl over her black dress in preparation to leave. Since the death of her husband, Esther Marsh had taken much comfort from the company of her new friend and neighbour, Rebecca Millgate. Meg suspected they would spend much of the next few hours on their knees at St George’s, for her mother had become devout under the influence of Mrs Millgate. She tried to be pleased that her mother had found such comfort in God, but it was hard to ignore the bitter truth that devotion alone would not put bread on the table or keep the roof over their heads.

Meg turned the sign in the shop window to read ‘Closed’, then removed the plate of buns. On closer inspection, they were older than she’d thought: traces of mould had started to appear among the whirls of dough. She made a face and carried them through to the kitchen. There was no point in throwing them out into the yard – they would attract rats. She would give them to their neighbour for the pigs he kept on the wasteland at the edge of town. And she would bake more buns, and a seed cake maybe, as she had promised her mother.

But a quick look at the shelves showed her that less than a handful of currants remained in the jar and not a single coin was to be found in the housekeeping pot, tucked behind the tureen on the dresser. Meg frowned. She suspected her brother, Samuel, of ‘borrowing’ the housekeeping to fund the time he spent at the inn.

Although Samuel chose not to drink at the Fountain, where Meg worked, he didn’t lack for choice in the town – every street near the seafront was home to at least one inn, while Beach Street, overlooking the sea, was said to have more inns than houses.

The previous month, Samuel had lost his job at the boatyard due to his poor timekeeping. It was a job his father had found for him, and the change in their fortunes since Mr Marsh had died had made it all the more essential: the shop brought in very little now, and although Meg’s work at the Fountain added to their income, it was barely enough.

It was the loss of Samuel’s wages that had pushed Meg to think about how she might increase her involvement in smuggling. There was hardly anyone in town who didn’t have some sort of part in it: from hiding goods, to transporting them or passing messages. Those who rowed the boats out to meet the French ships played an important role, but it was just the start of a lengthy process. When Meg had been a pupil at the Charity School, she had used the books there to teach herself a smattering of French. It had amused her father to have her write the messages the smugglers took to the french boats, or to translate the replies received. As Mrs Marsh’s devoutness grew after the death of her husband, she had made it plain she wouldn’t tolerate any involvement with smuggling by any of her household.

By then, though, it was too late. Meg had moved on from her role as occasional translator. Michael Bailey, who organised the Silver Street gang’s smuggling trips, had taken her to one side in the Fountain to ask her advice about fabrics, having been offered some samples of muslin and silk. Meg had been delighted, even more so when her suggestions had found favour with those looking to buy, so Michael, confounded by the decisions to be made, had suggested she might handle that side of their business. As long as she paid the gang a proper share of the profits, she was free to do as she liked. It made her meeting with Ralph Carter doubly exciting – and all the more important that she kept it secret from her mother. She would note it all down that night in her diary – the money she had received, the promise made, and her future plans. Meg liked to record all of her transactions, but she kept the pages well hidden from prying eyes.

She saw that she would have to use some of the coins she had earned the previous evening at the Fountain to buy the currants and anything else she needed for the baking. As she left the house again, to go to Widow Boon’s shop on Middle Street, Meg wondered about the whereabouts of her nephew Thomas, Samuel’s son. He was a cheeky scrap of a boy with unruly blond hair (always uncombed), golden-brown eyes and a gap-toothed smile that had won over his aunt Meg on many an occasion – usually when he’d been hauled home by a shopkeeper who’d caught him pilfering. Thomas always maintained that he’d just picked up something that had fallen on the floor and Meg, exasperated and amused by his indignation, generally gave him the benefit of the doubt. He was only seven years old but, since Mr Marsh had died, he had been running around the streets of the town all day with no one to guide or control him. His mother Eliza, Samuel’s wife, seemed to have given up.

Perhaps she could persuade the Charity School to take him on, Meg thought. Her attendance there had been due to her father’s insistence, and she had learnt to read and write. Thomas might do well if his reputation in the town hadn’t already spoilt his chance of being accepted. Meg had been sorry to leave – she hoped her own good record would help persuade the master to take Thomas. Maybe, if their business grew, she could employ him as a delivery boy after school, to keep him out of mischief.

By the time Meg was home again and sprinkling the currants onto a batch of prepared dough, she was once more filled with the enthusiasm she had felt that morning. The idea of developing a trade in run goods was more appealing to her than any of the other activities she undertook to support the family. It had become only too clear that Samuel didn’t have the strength of character to step into his father’s shoes, and her mother was still struggling to shake off her sadness over Mr Marsh’s death. Meg knew that, for now, it was up to her to prove the Marsh family were capable workers in order to regain the respect they had once had, when her father was alive.

Walter Marsh had been a big, burly man with a bushy beard and a pronounced limp, the result of an accident when two of the smugglers’ galleys had been thrown together in heavy seas. Walter, flung backwards off his plank seat, had been unable to dislodge his oar, which had pinned his leg at such an awkward angle, and with such force, that it broke. The injury had healed, but badly, and despite his determination, Walter was no longer an effective crew member. He’d retreated into anger and, following in the footsteps of his father, had taken up baking bread. The early-morning hours spent in the basement kitchen, preparing the dough to go into the oven at dawn, had also made him useful to his smuggling friends. He was always there, alert and ready to spirit away a delivery of contraband if the revenue men surprised the smugglers at work. The alleyway leading off Beach Street, as well as the rooftops of Prospect Street, had saved the Silver Street gang many a time.

With Meg settled at the Charity School, Walter Marsh had spotted an opportunity for Samuel at the boatyard. He knew that the owner had no son to take over from him and he hoped Samuel might progress to managing the yard. Samuel, though, had had other ideas. He hung around the smugglers’ gangs in the inns of the town, accepted by them because he was Walter Marsh’s son. Yet, in appearance and temperament, they could hardly have been more different. Samuel was slight, and his attempts to grow a beard like his father’s were doomed to failure. His fine fair hair produced patchy wisps on his chin, not the luxuriant growth he longed for, and although he talked up his bravery and prowess at sea, he was never included in the gangs’ runs to meet French ships. Disappointed, his visits to the inns became even more frequent, and if his father hadn’t hauled him out of bed in the mornings, he would have lost his job at the boatyard long before he actually did.

It was Meg who had found her father early one morning, more than a year earlier, slumped over the kitchen table, the loaves of bread neatly shaped and ready for the oven. She’d thought him asleep at first and laughingly shaken his shoulder. But although he felt warm beneath her hand, he didn’t stir, and when she bent to look at him more closely, his eyes were open, unseeing, and his soul had fled. Her terrible cries brought the whole family running, in their nightclothes and still half asleep. Meg wondered ever after whether she could have saved him if she had risen just fifteen minutes earlier.

The pain of that discovery haunted her and the consequences were making themselves known still. Samuel, without his father to insist he got up in the mornings, had lost his job at the boatyard. His efforts to find more work were hampered by his lack of enthusiasm. Esther Marsh tried to continue with the baking, but bread-making proved beyond her. She couldn’t adapt to waking at such an early hour and hardly had the strength to knead the dough. As a result, her efforts were rushed, the dough barely risen and the bread often burnt. Her customers drifted away to the bakeries along Beach Street, taking with them their custom for the buns once bought as a treat for the family when they had a farthing or two to spare. Meg had to leave off her education and find work, first trying her hand in the local laundry until she was glad to accept the irregular hours offered by Mrs Dunn at the Fountain. The landlady saw how the family were struggling and, in the early days after Walter Marsh’s death, she would send a dish of stew round for them. To avoid them feeling they were living off charity, it would be accompanied by a tactfully worded message, such as ‘Just scrag end, but I didn’t want it to go to waste.’

Mrs Marsh seemed bewildered by her husband’s death and had lost the spark that had once made her a feisty partner to him. Widowhood had diminished her and she had abandoned the reins of the household. Of late, Meg had more than once caught herself wishing that her mother had just a fraction of Mrs Dunn’s forthright manner.

While the buns baked in the oven and the warm aroma of cinnamon filled the kitchen, Meg sat down at the table, still strewn with flour and scraps of pastry, and indulged herself in imagining how she might grow her trade in run goods. Michael Bailey had let her take an oar in the smugglers’ galley on one of their runs, knowing that she had rowed frequently with her father from an early age and had more skill and strength than her brother. Philippe, the Frenchman they dealt with, had given her a glimpse of the more expensive fine fabrics and fancy goods he had and she had longed to be able to buy them. The silks and shawls were from India, he said, and she reached out to stroke the velvet and brocades, the likes of which she had never seen in Castle Bay.

She couldn’t afford them then, and there was no local demand for them, but the London trade would be a different matter. The greedy look in Ralph Carter’s eyes had told her that the ladies in the city would have an appetite for such things. If she bought and sold enough of the more regular items – ribbons and lace, muslin and cambric – she would be able to afford the purchases of the more exotic shawls and embroidered slippers, feathers and fine fabrics. And, eventually, maybe, a bolt of the beautiful silk in colours richer than her dreams. Then, if all went well, in five years’ time, or perhaps less, she could have a shop of her own in London. She imagined it to be very like the shop in Prospect Street, but with sparkling glass in the narrow bow window rather than salt-streaked cracked panes. Instead of a sad display of dusty currant buns, it would be draped with cloth in rich reds and ochres, cream Indian silk painted with beautiful fruits and flowers, and fringed shawls sporting bold paisley designs, while the finest kid gloves, beaded bags and embroidered slippers peeped out among all the glorious fabrics. Her heart beat faster at the very thought.

Instead of sleeping in her cramped attic bedroom, where the wind rattled the window in the winter, bringing with it the sound of the crashing waves on the shingle shoreline, she would have a room just above the shop. It would look onto the street, where horse-drawn carriages would deposit fine ladies at her door, and she would retreat there at the end of the day to light the fire, recline on her brass bed and … Meg’s imagination failed her. She couldn’t envisage how a successful shop owner might live, or furnish her rooms, or what she might eat. All she knew was that she saw herself alone in this rather hazy picture.

A husband didn’t feature in Meg’s plans for the future – for the immediate future, at any rate. She was only seventeen, after all, and there was plenty of time for that. Joseph Huggett, though, had made plain his attraction to her. He was at least five years older and a fisherman: as hazardous an occupation in its own way as smuggling. His earnings were dependent on his catch, which in turn was hostage to the weather and the tides. And even a good catch was worthless if the market was only interested in herring and the boat came home loaded with mackerel.

The smugglers and the fishermen had an uneasy tolerance of each other, threatened only once, a long time before Meg was born, when her father was a boy. He’d told her how the Lord Warden, who was responsible for the safety of the coast and the ports along that stretch, became furious at the amount of smuggling going on and the lost revenue associated with it. He’d ordered all the boats on Castle Bay beach to be burnt, employing the revenue men to carry out his orders. It was an indiscriminate burning: the fishermen’s luggers were torched alongside the galleys the smugglers used. Just a few boats still out at sea escaped the inferno.

The only people to profit from this were the local boat-builders; they couldn’t build new boats fast enough to satisfy the need. The smugglers, though, had money to spare – or they knew where to find it – and their willingness to pay more put them to the front of the line. The fishermen, who lived a much more hand-to-mouth existence, were reduced to trying their hand with nets off the beach. Even when they could finally procure a boat, they were forced to take out loans that reduced their income for years.

Then, just the previous year, the government had once more taken action – this time against the smugglers alone. They had seized the galleys – or at least the ones they could find: word of their intentions had got out and those who could muster the required number of men to handle the oars had put to sea. There they had waited, far enough out to be nearly invisible on the horizon, but close enough to see the signals that told them it was safe to return. This act by the government had damaged the large, organised smuggling operations, but left room for the small local gangs to operate. It was here that Meg saw the chance to make her profit. And although Joseph was undoubtedly the most appealing of the regulars at the Fountain, she reasoned that as a fisherman he wouldn’t provide her with the sort of future she was looking for.

She wasn’t entirely sure what that might be. Making a connectio. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...