- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Kent 1816. Now Molly Dawson's family have grown up and left home, she has every reason to expect that life with her husband, Charlie, will settle into happy contentment. It seems, though, that her estranged half-sister, Harriet, has other ideas. When the secret Molly has kept for over 25 years is revealed in front of her whole family, Molly's relationship with her son and her husband begins to crumble. And when she takes a trip away from home to allow things to settle, Harriet steps in - with devastating consequences. Will Harriet prevail, or can Molly win back Charlie's heart, and heal the rift with the son she had been parted from for so many years?

Release date: January 27, 2022

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 100000

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

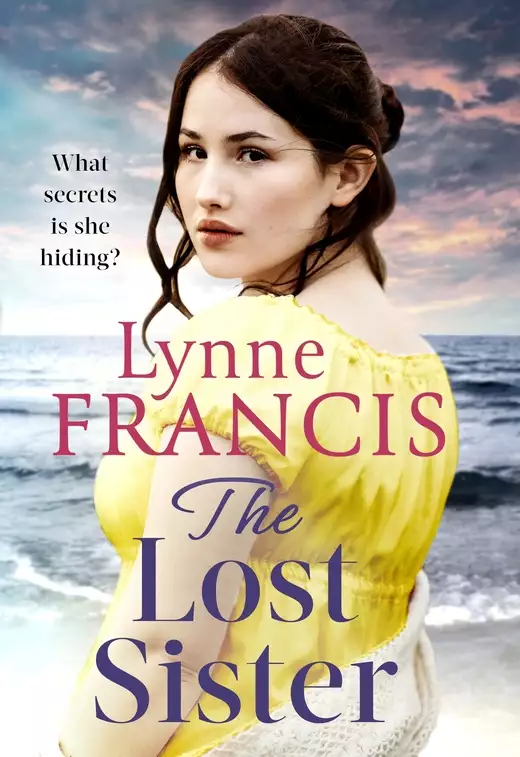

The Lost Sister

Lynne Francis

Their humours tended not to vary. On the whole, they were full of complaints – usually about their doctors’ insistence that they must be exposed to the maximum amount of sea air each day. Or about the charity cases – impoverished Londoners suffering from scrofula, an affliction affecting their glands, joints and bones – for whom the hospital was originally founded. I was, on occasion, forced to remind my patients that at least they didn’t have to spend each night sleeping in the open air, as the charity cases did. To my surprise, though, they rarely complained about the sea bathing, the cornerstone of their treatment programme. One and all, they were impatient for improvement in their condition and hoping for relief from their damaged lungs.

Throughout my time working at the Royal Sea Bathing Hospital in Westbrook, I had my doubts as to the efficacy of the treatment but, since it kept me and others in employment, you would never catch me saying anything other than soothing words to the patients. I had regular work, and although the money wasn’t very good and the lodgings even worse, I needed to stay there for as long as I could – or so I thought then.

I had become used to having only myself to look after, since my mother had remarried and my brother John had been incarcerated in Maidstone gaol. I had, I thought, resigned myself to a life of hard work with but a few simple pleasures – a new frock every now and then, ribbons for my bonnet, the loan of a novel from the lending library in Hawley Square. I might long for a gown of Indian silk, but such finery would be wasted. Since I had moved to the edge of Margate, from Eastlands Farm, I had had no cause to travel further afield.

I had family in the area but we had lost touch more than twenty years earlier and I did not seek them out. They would enquire after John and I was hard-pressed to come up with a convincing lie. Years of petty crime and brawling had culminated in his latest sentence of five years. I could have invented a new life for him somewhere distant – London, Scotland, Australia perhaps. Although the latter was too close to where he would inevitably be sent if he transgressed again. That or the gallows. Meanwhile, the risk of his reappearing once his sentence was over, in search of whatever money I might give him to go away again, meant his existence was best kept quiet.

I had taken a different name, in an attempt to distance myself from my brother’s notoriety. I had been Harriet Goodchild when I moved to Eastlands Farm. Now, having adopted my mother’s maiden name, I was Harriet Dixon. It was a gesture of rejection of my father’s family too, I suppose. They had abandoned me, after all.

I have taken care to acquire a small nest-egg, built up in the course of my work but not necessarily as a result of my own efforts. It was the decision by the hospital trustees to fund the charitable patients by taking private ones that played into my hands. Not all of these private patients were careful about where they kept their jewellery or small amounts of cash. It was hardly my fault if rings discarded thoughtlessly on bedside tables apparently slipped down between the floorboards. I was always meticulous in warning the patients of such hazards; even so, several items of jewellery vanished in this way.

Gentlemen, I noticed, were equally careless of how they emptied change from their pockets before divesting themselves of their clothing in preparation for immersion in the sea. They rarely, if ever, noticed the absence of one or two coins and it soothed me to see how quickly small amounts added up to something more appreciable. Soothed me because, it has to be said, I was not always sanguine about where my life had taken me. Like the sea that I watched with increasing frequency from the windows, I had been buffeted by life – dragged under and flung out to a place not of my choosing.

It was neither the sea nor the hospital treatments that led me back to my half-sister, Molly, after more than twenty years. It was the hospital garden – which I’m sure Dr Lettsom, who ran the hospital, saw as his greatest accomplishment when I started work there in 1815. By then, the hospital had been open under his guidance for nearly ten years and the garden was well-established. On the days when Dr Lettsom was at the hospital he was as likely to be found out there, clipping and watering alongside the head gardener, as he was to be in his office. He said the garden was for the benefit of the patients, although few seemed inclined to take advantage of it.

I discovered later that it was on his London estate that Dr Lettsom had first met Charlie Dawson, who was to play such a key part in my story. Charlie made regular plant-finding trips for the Powells at Woodchurch Manor; one to Dr Lettsom’s beloved garden. Dr Lettsom was delighted to discover a plantsman living so close to his hospital in Kent – no more than a couple of miles away as the crow flies – and he invited Charlie to Westbrook. He’d been visiting the garden for a little while when I first had cause to speak to him, and that was only because I was in search of Dr Lettsom.

It was a hurried enquiry, driven by the need to find the doctor: one of the patients had become particularly quarrelsome and declared his intention to return to London. The doctor was nowhere to be found within the building so the overseer, Mrs Murray, sent me to look outside in the gardens.

Finding a man at work in the borders, I asked him whether he had seen the doctor. My query was initially impatient, conscious as I was that Mrs Murray was waiting. But I barely heard the man’s response, ‘The doctor has gone to Margate with a promise to be back before too long,’ for I was so arrested by his appearance. When he straightened, I saw that he was a good deal taller than me, with a well-tanned face and hands. The smile he gave as he replied crinkled the skin around his dark brown eyes. I judged him to be about a decade older than I was, for his hair had a few threads of silver, but his slender, wiry build could easily have been that of a much younger man.

I found myself blushing as I thanked him and hurried back inside, knowing I would have to appease Mrs Murray for returning without the doctor. For the next hour or so, I caught myself glancing out at the garden whenever the opportunity arose, hoping for further glimpses of this man at work. Of course, I didn’t know his name at this point, but it was easy enough to find out from Dr Lettsom. I saw the doctor return from Margate, walking in his usual brisk way despite the warmth of the day, and hurried down from the room where I was folding laundry to meet him in the hall.

I told him that I had been in search of him earlier, but that the man in the garden – here I paused, hoping he would supply the name – had told me he had gone on an errand to Margate.

‘Ah, Charlie. Charlie Dawson – the head gardener from Woodchurch Manor. I do hope he is still with us and hasn’t had to return. It took me longer than I thought to see to business in town.’ Dr Lettsom looked flustered. ‘But first I had better attend to the problem with Mr Conway.’

I would have offered to take a message out to the garden but Dr Lettsom clearly expected me to be at his side while we went in search of Mrs Murray. I was distracted while the issue with Mr Conway was resolved, for the name the doctor had given me had stirred an elusive memory. I felt sure it was familiar to me from my childhood, too far back to remember it with any clarity. I resolved there and then to meet Charlie Dawson again to find out more.

It was, perhaps, no coincidence that I began to pay more attention to my appearance at work each day. My uniform was surely pressed with a little more care and my dark hair pulled back a little less severely under my cap, although still neat enough to satisfy Mrs Murray. I may also have tried out some different expressions before the glass in my room, aware from the frown lines on my brow that I was in danger of looking like an old maid.

For old maid I surely was – twenty-nine years old, with no husband and no prospect of one, unless I was prepared to take on one of the pot-bellied men of the so-called genteel class in Margate; one of those somewhat older than myself whose wife had departed this life, worn down by the toil of looking after the household and the children and listening to her husband’s complaints. Is it my fault if I began to wonder whether there might be another way to achieve the sort of life I surely deserved after the hardships I had endured?

I began to make it a habit to take one of the patients, old Mr Walters, out into the garden each day, judging him the least able to demur. I’d told Mrs Murray that I had reason to believe Mr Walters missed his own garden and that he took pleasure in our daily perambulations, with me pushing the heavy and somewhat creaky Bath chair along the gravel paths. My efforts had been rewarded by a growing acquaintance with Charlie, whom I had discovered would call by the garden at regular intervals. He would arrive bearing cuttings or recommendations of plants that Dr Lettsom might try, to see if they would withstand the salt-laden breezes that the doctor declared plagued his attempts to replicate his London garden.

I had progressed from nodding polite greetings to Charlie to stopping to ask him about various plants as he worked in the borders, relaying the information received loudly to Mr Walters. My patient appeared somewhat bewildered by this but so far hadn’t given voice to his confusion. In any case, his deafness meant that many other members of staff at Westbrook assumed his other faculties were affected, too.

‘And have you always lived around here?’ I was hoping that Charlie’s answer to my apparently casual enquiry would reveal where our paths had originally crossed and I wasn’t disappointed.

‘I’ve lived and worked at Woodchurch Manor for more than twenty-five years now, but before that I was at Prospect House in Margate.’ Charlie’s expression clouded and he frowned as he bent over his spade. ‘That’s the poorhouse. I lived there and I was apprenticed to the head gardener, Mr Fleming. He’s dead now.’ Charlie sighed. ‘He was very good to me. He set me on the right path and I owe everything to him. I wish I’d made more of his company. It’s too late now.’

‘I’m sorry to hear that,’ I said. ‘It’s so often the way. We think we will have plenty of time to spend with our friends and family at some point in the future. Then, before we know it, they’ve gone.’ I made my voice as sympathetic as possible and adjusted my expression to suit, but inside I was jubilant. I knew at once who he was and our paths had indeed crossed when I was very young. I wasn’t sure, though, whether to reveal this now or save it for a later date.

I was spared that decision by a call from the house, asking me to bring Mr Walters back as he was due his sea immersion. It was to be several days before I came across Charlie in the gardens again, but by then I had planned what I needed to say to him. I was out with Mr Walters in the Bath chair once more – by now Dr Lettsom was completely convinced that the gardens were beneficial to him – and I wasted no time in speaking to Charlie.

‘I’m so pleased to meet you again, Mr Dawson,’ I said, with no preamble whatsoever. ‘It came to me after we last spoke that we have met before, although I don’t remember a great deal about it. My half-sister used to take me to the Prospect House gardens when I was very small, along with my brother John. I’m afraid my main memory is that there was cake, and lemonade too.’

Charlie frowned. ‘Your half-sister – do you mean Molly? Why then you must be …’ He paused, and I could see he was searching his memory. ‘Harriet?’ He stopped what he was doing and stared at me. ‘You were a little scrap of a thing back then. Molly will be so pleased to hear that I’ve come across you. I know she wondered what became of you.’ He paused again. ‘We’re married, you know, Molly and me.’

I nodded vaguely, although he was too caught up in shaking his head in wonder to notice. Of course I knew they were married – my mother had told me. I also knew that none of my half-sisters – Molly, Lizzie or Mary – had made any efforts to find out what had happened to me when our father died. They knew what my mother was like, yet they let her take me and John away from the family and all I had ever known to that God-forsaken farm of her father’s in Eastlands.

John was always her favourite, the one she indulged, while she set me to work helping around the house. I was only seven or eight and could barely see over the copper, but she’d have me pounding the family washing when I wasn’t peeling vegetables or feeding the pigs. Not that she stayed there for long. Before a year had passed she’d married again: a neighbouring farmer with two sons of his own. She said it was more convenient for John and me to stay where we were, on her father’s farm. No other members of the family ever thought to look for us.

I didn’t say any of this to Charlie. What I said was, ‘Oh, I do so hope I can meet Molly again. She took good care of me when I was small and it’s been such a long time since I last set eyes on her.’

‘Well, we must remedy that,’ Charlie said. ‘I’ll speak to her tonight. I’m sure she will want to arrange a meeting very soon. Imagine coming across you here, like this.’ He was still shaking his head in astonishment as I excused myself, saying I should take Mr Walters back inside.

To begin with, I was mainly curious. Why had the family given me no thought once I was gone? It was because of Ann, my mother, I expect. I saw how people were around her. Men were eager to do her bidding but a little frightened of her. Even her own father.

‘She’s a difficult woman,’ I heard him say to John, when he demanded to know why she’d left us. ‘She does what she thinks is best.’

Were the women of the family scared of her, too? It was something I wanted to know. My mother was cold and indifferent to me, so perhaps I had got off lightly. I could shrug off her moods when we first moved to Eastlands Farm, and later I tried to ignore her desertion of us.

I could, in fact, remember more of my early years in Margate than I let Charlie think. Lizzie and Mary had looked out for me as I grew, but before then it was Molly who made sure I was well cared for. She lived next door at the time – a result of her not getting on with my mother, I think. Molly made sure to take John and me out regularly – most often to the gardens at Prospect House. When one of my mother’s black moods came upon her, it was Molly who made sure I had a clean pinafore and my hair was brushed, and that we’d at least dined on bread and jam if there was nothing more to be had.

Now those days in Margate appear to me as if they were bathed in a golden glow. By contrast, the days at Eastlands were cold and damp, summer and winter, in a farmhouse that was tumbling down through lack of care. Our grandfather fell ill shortly after we arrived, which was probably when our mother decided it was time to move on. She didn’t intend to play nursemaid to anyone. That role fell to the cook and, as I got older, increasingly to me. I suppose the best you can say about caring for my grandfather is that it helped me to get the job I have now. There was no need to lie in that respect.

I’d changed my mind about not wishing to see my family. I was curious to meet Molly again and discover why John and I had been abandoned. At that point, I don’t think there was anything more to it. But the meeting I had begun to look forward to was unaccountably delayed: as summer came to an end, I hadn’t encountered Charlie again and all too soon the hospital closed in the autumn, as it did every year.

Dr Lettsom’s death late in 1815 came as a shock to us all. It meant that none of us knew whether we would have jobs to return to in the spring of the following year. At that time, the hospital shut between October and March because the sea was too rough for the immersions, and the weather too chilly to spend all the hours outside that the doctor recommended. Sleeping outside in those months would have been the death of many of the patients – not necessarily a bad thing, in my view.

I was relieved on two counts when I received word that the hospital was saved: I would have a steady income to rely on once more, and there was the prospect of seeing Charlie again. I was worried, of course, that with Dr Lettsom gone, Charlie had no reason to continue visiting the hospital gardens. I passed a few anxious days looking out for him and I had just decided that I would have to ask the head gardener about him when, through the windows, I spotted him. Mr Walters’s treatment had finished and he had returned to Bermondsey at the end of the previous September. I needed another excuse to be outside.

In fact, it proved easy enough. The patients, encouraged to take the air as often as possible, were usually to be found on the terrace overlooking the sea, as the breezes there were considered so beneficial. That week in March there was still a chill in the air and I noticed Mrs Pearce shivering, despite the blanket wrapped around her legs.

‘Can’t I be moved out of this wretched wind?’ she complained.

‘I could take you for a turn around the gardens,’ I suggested, and she agreed at once.

The gardens were on the more sheltered side of the building and Mrs Pearce, unlike Mr Walters, was fit enough to walk. We spent some time examining the new shoots appearing in the borders and the leaves beginning to unfurl on the trees, before she professed herself a little breathless. I settled her on a bench in the sun, to rest and listen to the birds singing, for I’d spied Charlie just leaving the glasshouse at the end of the garden. I excused myself to Mrs Pearce and hurried to catch him before he departed.

‘I’m so pleased to see you here,’ I said. ‘I feared that with the sad loss of Dr Lettsom you might not visit again and I didn’t want to lose touch.’

‘A sad loss, indeed.’ Charlie looked grave. ‘I will miss my discussions with Dr Lettsom, and it is true that I will be here a good deal less frequently now. But I’m glad to see you at last, Harriet. I had hoped to come across you before the closure last autumn, as I had an invitation for you. Molly wanted me to ask whether your work allowed you a free afternoon and, if so, whether you might be persuaded to come out to our cottage at Woodchurch Manor?’

I told him that I had every second Sunday afternoon free and would be delighted to visit them, if that wasn’t an inconvenient day.

‘I’m sure it will suit well,’ Charlie said. ‘You must come on your next free Sunday,’ and so it was arranged for the following week and their address committed to heart.

I dare say Mrs Pearce had barely noticed my absence, for she had fallen into a doze and was none too happy when I suggested it was time to return to the seaward side of the hospital. I had accomplished what I needed and had no great interest in spending any more time in the garden.

I took some care when dressing for my first visit to Molly and Charlie, choosing my plainest frock but taking delight in being able to wear my hair in a freer style than usual, with only my bonnet to confine it. I thought of my hair as my crowning glory. Almost black in hue and luxuriant in its growth, it tended to fall in natural waves. I must have inherited it from my father, for my mother’s hair was fair. I think she disliked me for it, for whenever she brushed it when I was young she tugged on the hairbrush, yanking my head back, and complained about knots and tangles. Thinking about it now, I realise that she never once paid me a compliment.

I walked over to the Woodchurch Manor estate, taking pleasure in the spring sunshine. It felt good to escape the confines of the hospital, even though I had only recently returned to it. I’d spent the autumn and winter caring for the elderly father of a London family, a post that Dr Lettsom had found for me. They’d tried to persuade me to stay and if it hadn’t been for my wish to reacquaint myself with Charlie, and Molly, I might well have done so. But I was glad now to be back in the fresh air of the countryside and my heartbeat quickened with anticipation at the thought of seeing Charlie and Molly again.

Charlie had provided good directions to the cottage and I caught but a glimpse of the splendid house that had to be Woodchurch Manor, before I turned off on a quiet lane leading directly to their front door.

Molly must have been watching me walk up the garden path for she answered my knock almost immediately.

‘Harriet!’ she exclaimed, stepping back to usher me in. ‘Let me take a good look at you. Why, I don’t think I would have recognised you.’

She led me through to the parlour, glancing back and smiling over her shoulder as we went. ‘How well you look,’ she said, encouraging me to take a seat by the fireplace.

I would have been hard-pressed to say the same of her. She had aged a good deal since I’d last seen her – hardly surprising, I suppose, given the amount of time that had passed. I was shocked to see her chestnut hair now faded, and her face more lined than I remembered it. But she was talking and I needed to pay attention.

‘I’ve often wondered what became of you, Harriet, and wished that we could see you again. But Ann spirited you away to her father’s farm and here we are – all those years behind us.’

I thought she looked a little uncomfortable at her own words but she moved on swiftly. ‘And how is your mother?’

‘Well, as far as I know,’ I said. ‘She married again, shortly after we moved to Eastlands, and I saw her only rarely after that.’

Molly looked shocked. ‘Oh, Harriet, I had no idea. That must have been very difficult for you. And for little John. How is he?’

‘Hardly worthy of the name “little” any more,’ I said, ‘for he is as broad as he is tall.’

‘And does he live close by? Do you see him often?’

Molly was hovering by the door and I knew she was eager to go and set the kettle on the range and attend to the tea.

‘He’s in Maidstone gaol,’ I said, taking delight in the effect that my words had on her.

‘Oh, my goodness.’ She sat down suddenly in the nearest chair, her previous intention to depart to the kitchen now forgotten.

At that moment Charlie came in and looked between us, sensing something amiss. He went to stand by Molly and put his hand on her shoulder. She reached up to cover it with her own.

‘Is all well?’ he asked.

‘Oh, Charlie. Harriet has just told me that little John – I mean, John – is in Maidstone gaol.’

I thought Charlie seemed less surprised than Molly, but he politely enquired as to the background to this sorry state of affairs.

I filled them in as briefly as possible, then Molly departed at last for the kitchen, leaving me alone with Charlie.

‘You have a beautiful cottage,’ I said, looking around the room at the polished wooden furniture, the grandfather clock ticking in the corner, the samplers hung on the wall by the fireplace. ‘Have you lived on the estate for long?’

‘Aye. I’ve been here since I was seventeen, straight from Prospect House back in 1788. Molly joined me here three years later. It suits us well. Mr Powell and his sons are a good family to work for.’

I delayed enquiring about his own family until Molly returned, asking him instead about the nature of his work on the estate. I was listening as he spoke but barely took in a word of what he said. Instead, I watched his hands move, fascinated by his long, strong fingers, which he used to emphasise a point.

Once Molly had returned and set the tea things on the table, politely declining any offer of help, I asked her whether she and Charlie had any children.

‘Oh, heavens, yes! And grandchildren, too.’ She told me about their four children: George, Sally, Agnes and Catherine, and their grandchildren – Grace, Simon and Eleanor.

‘And George and Judith married last summer so we’ll have another on the way before long.’

From the fond look that passed between Charlie and Molly, I could see what a strong bond they had and how important their family was to them.

I’d never had anything like that. It cut me right to the core.

By the time I began my walk back to the hospital later that afternoon, I had recovered. I told myself that, after such a length of time, my first encounter with Molly had gone well. I’d expressed an interest in renewing my acquaintance with the rest of the family, as well as my other half-sisters, Lizzie and Mary. I felt I had been quite respe. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...