- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

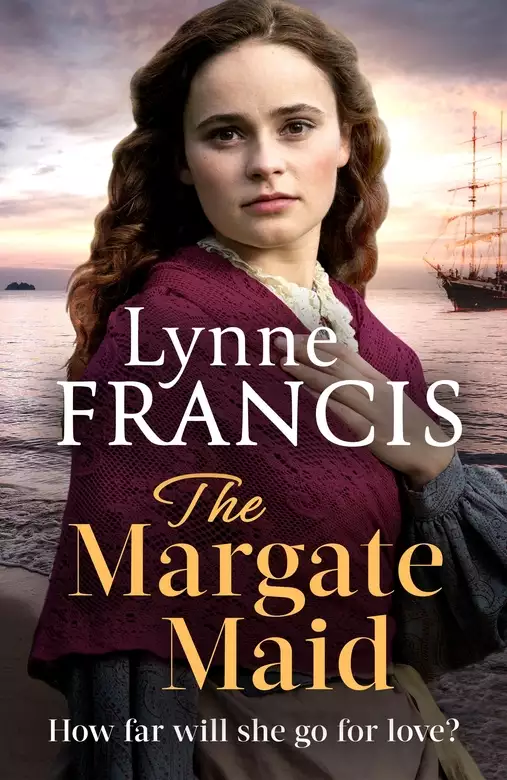

A brand new saga of love and betrayal in late 18th century Kent and London from saga author Lynne Francis, perfect for fans of Dilly Court and Rosie Goodwin.

Margate, 1786. Dairymaid Molly Goodchild dreams of a better life. Up at the crack of dawn to milk her uncle's cows, the one comfort of her day is her friendship with apprentice gardener, Charlie.

When dashing naval officer, Nicholas, arrives in town, Molly's head is turned by his flattering attentions and she casually spurns Charlie - believing this is her chance to escape a life of drudgery. Yet when Molly needs Nicholas most, he lets her down.

With her hopes in tatters, Molly is forced to flee Margate for London, where she finds herself struggling to survive.

What will she risk in her search for a better life? And will she ever find the love she deserves?

Release date: March 5, 2020

Publisher: Piatkus

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

A Maid's Ruin

Lynne Francis

The boy looked confused, as if trying to work out what he had done wrong. ‘I’m drawing,’ he said. ‘Do you want to see?’

She glowered at him, but really it was her uncle William she was angry with, not this boy, whom she’d never seen before. His blond hair, wavy and long, was loosely pulled back into the collar of his brown wool jacket, a heavy lock falling over his forehead. He looked a little younger than she was and small for his age, perching on a tumbledown part of the wall with a book of paper on his knee. Truly, Molly thought, he hadn’t done anything to deserve her anger. She moved a little closer and peered at what he was doing.

‘Why, you’ve captured it well!’ she exclaimed. She walked round him to stand at his shoulder and squinted at the church he was drawing.

‘Where did you learn to do that?’ she asked, unable to disguise her admiration.

The boy shrugged. ‘I don’t know. At school, I suppose. I’ve always been able to draw.’

‘You go to school?’ Molly felt cross again. She had wanted to learn but her father and uncle had said it was a waste of time. What need would she have of book learning? they asked. They already had a life mapped out for her: a milkmaid for her uncle and a dairymaid for her father, selling the milk to those who came by the stable-yard in Church Street. Married before she was twenty, no doubt, and a houseful of children to follow. It wasn’t at all what she had in mind.

She was making her way to Church Street now from her uncle’s barn, where she’d had a falling-out with him. He had said her bad temper at milking time was making the cows yield less, and accused her of spiteful squeezing of their teats. She could have told him that the poor yield was because they needed fresh pasture: the grass had been over-grazed and was no longer rich enough. But she was barely fourteen years old and he wasn’t going to listen to her.

Molly had cut through the churchyard, hoping that the peace as she walked between the yew hedge and the gravestones would calm her before she set to work in the Church Street dairy. Ahead of her was a morning of ladling out the milk from a great churn to whoever had the farthings to pay for it, while her father took the other churns on his rounds in the horse and cart.

She knew she was going to be late, but her admiration for what the boy was creating on the page had made her curious.

‘I must go,’ she said eventually, as the church clock struck eight. ‘My father will wonder where I am.’ She turned to leave, then stopped. ‘What’s your name?’ she asked.

‘Will. Will Turner.’

‘Molly Goodchild,’ she said, although he hadn’t asked. ‘Perhaps I’ll see you again.’

Molly’s day had begun before dawn, when she’d risen from her bed in the room she shared with her younger sisters, Lizzie and Mary, and crept down the stairs, boots clutched in her hand. The cows would be plodding towards her uncle’s barn from the fields, and by the time she arrived they would be jostling for space, filling the air with their warmth and ripe smell. A mix of fresh grass, milk and muck, Molly thought wryly, as she sat on the bottom stair to lace up her boots. She hadn’t even bothered to wash her face – she’d fallen into the habit of washing after her return from her morning’s work, seeing little point in doing the job twice.

She closed the back door of the cottage behind her, then hurried through the yard and out into the alley that led into Charlotte Place. From there she could cut through the grounds of St John’s Church and be at the field edge in no time. Molly pulled her shawl around her, glad of its warmth – even though it was spring it was still chilly so early in the morning. As she started to cross the field, fingers of light crept across the sky, released by the sun rising over the sea. She felt the damp strike through the thin soles of her boots and picked up her pace, welcoming the thought of the warmth of the cow barn.

The lowing of impatient cattle, waiting for their milkmaid, carried over the final stretch of field. Thomas, her uncle’s cowman, shook his head as she all but ran the final stretch across the yard.

‘He’s not best pleased with ye,’ he said as she passed, untying her bonnet and pulling off her shawl. Molly turned her head and stuck out her tongue, hearing Old Tom splutter with laughter just as she came face to face with Uncle William.

‘Late again,’ he said grimly. ‘I told that feckless brother of mine I’d give him a hand when Sally died, Lord rest her soul, so I’d expect you to be grateful enough to get yourself here of a morning in good time.’

Molly had been about to offer an apology until her uncle had mentioned the death of her mother. She drew her brows into a frown, convinced that her long, wavy chestnut hair, now released from her bonnet, had fallen far enough across her face to disguise her scowl. But her uncle added, ‘You’ll be frightening the cows with that face on you. It looks set to freeze the blood.’

She ignored him, taking her smock down from the peg and hanging her bonnet and shawl in its place. Then she went to fetch the milking stool and the metal pail, settling herself in the nearest stall where a cow already waited. The bucket grated on the stone floor as she pulled it into position and the animal shifted uneasily. Molly rested her forehead against its warm flanks and tried to still the hammering of her heart. She was out of breath from hurrying and also furious at her uncle’s words. She didn’t want her feelings to transfer themselves to the cow, and to the rest of the herd. They were sensitive to mood and to the way they were treated. Molly forced her fingers to work rhythmically, uttering soothing words as accompaniment.

‘I’m a bit late but we’ll soon sort you out. Hmm? Hmm? No need to get into a bother, is there now?’ The words were directed at the cow – but aimed at her uncle. Molly thought she’d kept her voice low, but he was hovering, watching her. His sharp ears caught her words.

‘I’ll not speak to you about it again, Molly. There’s plenty of other girls around here who’d be glad of regular work. They’ll be on time and work hard, without giving me and Old Tom any cheek.’

Molly made a face at the cow’s flank. As the milk eased to a trickle, then ceased, she stood up, patted the animal’s neck and emptied the milk into the churn before she took her stool and milking pail to the next stall. It would be easier if there was more than one milkmaid, she was sure, but her uncle maintained his herd was too small to require it, so Molly worked her way along the five stalls, milking each cow in turn. Old Tom sent them back into the fields with a slap on the rump, then led in another to wait patiently in a stall.

Molly tried to calm herself and clear her mind. She didn’t want to make the animals uneasy, and her own job harder. But the unfairness of her uncle’s words stung.

It was hardly her father John’s fault that his wife had died, Molly thought. Her mother, Sally, had faded away after the birth of the youngest, christened Alfred but known to the family as Boy, and she’d died six months later. Boy had followed shortly after. Molly, aged nine, found herself mother to Lizzie and Mary and to her own father. He’d lost his job as a carpenter when her mother had died, grief and despair rendering him helpless and unable to concentrate.

His brother, Uncle William, had found him work at a corn merchant’s, in a much lowlier post. William, who had been very fond of his sister-in-law, viewing her as the sensible one of the family, saw it as his duty to help his brother’s family. He’d been furious when, three months into the new job, John had met Ann, a young woman barely ten years older than Molly, a farmer’s daughter who delivered his sacks of grain to the corn merchant. John and Ann were married within the year and a baby was born not six months after.

Molly had heard her uncle shouting at her father when he’d told him of the marriage plans.

‘So you couldn’t wait, eh, John? Sally barely cold in her grave and you’re having Ann up against the corn sacks?’ Her father had shut the kitchen door after that so she didn’t hear his reply, and Molly had pushed the little ones up the stairs to their bedroom so that they weren’t upset by the quarrel.

Molly had mixed feelings about her new stepmother. She was grateful to have an extra pair of hands about the house but disliked the way that Ann hung on her father’s every word. She monopolised his attention and seemed to want to sit on his knee just as much as Lizzie and Mary did. Of an evening, after they’d eaten their supper, she’d follow him around, draping her arm about his waist and whispering in his ear until Molly could bear the sight of it no more and took herself away. In summer, she’d go out to the fields and wander across them as the sun set, watching the rabbits at play, or she’d sit by the shallow pools of the Brooks, where dragonflies hovered and water voles plopped into the water at her approach. She returned as late as she dared, steeling herself for a scolding from her father for going off without a word. In winter, she’d turn her back on the pair of them, taking a basket of mending and going to sit by the fire. Or she’d take a candle up to her room with the one book that the house possessed, the Bible, trying to spell out the words there that she recognised.

It was hard to escape the influence that Uncle William had over Molly’s family and their lives. He was their neighbour in Princes Crescent, along with his wife Jane and their three children. Although her uncle’s house was next door, it was much grander than theirs. It sat in a terrace of five houses that stood high above their neighbours’ much smaller and rather down-at-heel cottages. Each of those houses was set over three floors, with an additional basement – a sign to one and all that they could afford servants – and their drawing rooms were elevated above the street, giving them an airy outlook. Uncle William’s house had a proper garden at the back, rather than a yard, with a lawn and flowerbeds. Aunt Jane grew roses there and sometimes sat out on a summer’s evening with her husband. Before Molly’s mother had died, her family would occasionally join them, the children playing while the adults chatted. This hadn’t happened since her mother’s death, and Molly missed it.

Once John had remarried and Molly was needed less around the house, it had been Uncle William’s decision that she must work. The position of milkmaid was less an offer, more of a command, and Molly was pretty sure that it suited her uncle’s purpose very well and wasn’t simply a charitable move on behalf of his brother’s family. He’d also suggested to John that he should give up the job at the corn merchant’s and work for him, distributing the milk produced by his cows. Demand had grown and he had increased his herd accordingly, shrewdly seeing a future business in the making.

Uncle William’s proximity meant that she had no chance of escaping his eagle eye. Even though Molly had started to leave her home by the kitchen door and the yard, rather than the overlooked street entrance, it felt to her that her uncle kept an eye on her every move. He himself worked hard to keep his own family well provided for, having fingers in many pies around the town. He not only kept a herd of cows but had an interest in a corn business and a bakery. In keeping with his determination to be seen as someone of note, he was a trustee of Prospect House, the poorhouse nearby, taking his role seriously, visiting regularly and always keen to find gainful employment for the inhabitants.

Molly’s day – which had not begun well after the argument with her uncle – had improved following her encounter with Will. She wondered about him as she made her way to the Church Street yard, where her uncle’s milk churns would be delivered, ready for distribution around town. The fact that Will was at liberty to sit with a sketchbook in the churchyard on a weekday morning signified he wasn’t in employment, while his accent and clothing set him apart from anyone she knew. She resolved to find out more, for surely he would be back in the churchyard sketching again at some point. But, for now, she had arrived in Church Street and her father was standing at the yard gate, on the lookout both for her and the cart carrying the churns.

‘A lovely morning, Molly,’ he observed, as she approached. The sun picked out the silver threads running through his once-dark hair, and his habitual worried expression was erased by the smile he gave her. She smiled back and reached up to kiss his cheek. Private moments with her father were few and far between and all the more precious since his marriage to Ann. This short period each morning, before he set off on his rounds, was all that Molly had left to remind her of how their life used to be.

Stopping only to wash her hands at the pump, with the block of harsh soap that always made her skin feel as though it had been flayed, she went into her father’s cubbyhole of an office. It was at the back of the stable, empty now because the horse was standing in the yard, stamping his feet and jingling his harness, impatient to be off. The office was barely deserving of the name, being just big enough for a chair and a small table covered with an untidy pile of papers. It smelt strongly of horse, as always. Molly put on the white apron that she always left hanging on the hook behind the door, noting as she did so that it would need to be taken home for washing at the day’s end. Tying the strings behind her she picked her way back through the stable, wrinkling her nose.

‘Has the boy not been yet?’ she asked her father, who was now leaning on the gate, ear cocked, as he listened for the arrival of the milk.

‘Not yet. I’m sure he’ll be here soon.’

Molly sighed. The stable lad came from the poorhouse each morning, employed to do menial jobs. The cleaning of the stable looked beyond him, though, for he was small and undernourished and looked hardly able to lift the pitchfork, although he stoutly maintained that he could manage. He’d been with them barely a month, and in the last week he’d been late every morning. Molly’s father, a gentle man, refused to say anything about this to her uncle who had arranged the boy’s employment.

‘Let’s give him a chance, poor thing,’ her father had said. ‘I daresay he’s barely seven years old and he’s got a cough that will see him into the ground at St John’s if he doesn’t shake it off. If he’s late a few days it does no harm.’

Molly privately thought that for the customers who came to the stable-yard to buy their milk it was nicer to be greeted by the aroma of freshly laid straw than by the stink of horse manure, but she kept her counsel. Her father was right to worry about the boy. She had taken the pitchfork from him on more than one occasion and bade him rest to ease his cough, while she finished the job.

The metallic ring of a horse’s hoofs on the cobbles announced the arrival of her uncle’s milk churns just as a boy arrived at the gate.

‘Customer, Molly,’ her father called, busy helping the cart back up so the churns could be unloaded. ‘Can you bid him wait?’

Molly looked the boy up and down. She had at first thought him to be the stable-boy, grown in stature by at least a foot overnight. He wore the same sort of garb – a loose working jacket and trousers that were too short, as well as ill-fitting boots with snapped laces, much worn around the toes and heels. But as he approached she saw that he was a good deal older, closer to her own age perhaps. He had a shock of brown hair that looked as though he had slicked it down at the pump that morning when he set off but, dry now, it had half sprung back to its usual boisterous state. He looked nothing like her usual customers, for the most part local women or their small children, all of whom she recognised. Before she could ask him who he was, he introduced himself.

‘I’m Charlie. I’ll get going with the jobs, shall I?’ Before she could reply he’d turned on his heel and leapt onto the back of their cart, causing the horse, Nell, to start and look around in astonishment. Charlie beckoned to her father to hand the churns up to him. Molly could see that her father was bemused, but he wasn’t about to decline the offer of help. Manhandling the full churns onto the cart was a difficult job for him – he wasn’t a great deal taller than Molly herself.

In contrast to his brother William, who was broad and tall, and carried himself with an air of importance, Molly’s father always looked a little apologetic about his existence. As a result, her uncle’s delivery men never seemed to feel they should offer to assist. Once the churns were unloaded from their cart they would doff their caps to Molly and her father, then give the reins a shake to encourage the horse to set off at a brisk trot down the road. Molly’s father was left to manage his own affairs.

Charlie made short work of the loading, then rolled the last churn over to the corner of the yard as directed by John. The churn left behind was always placed in the shadiest spot, beneath the branches of an overhanging tree from the orchard next door, Church Street being at the limit of the town, with countryside stretching out to south and west. Shade wasn’t necessary now, but as the sun crossed the yard during the morning it would help to keep the milk cool until most of it had been sold, usually by midday.

‘Thank you, lad,’ her father called from his seat on the cart. Then he shook the reins and off they went, to visit the three big squares closer to the centre of town. Here the kitchen-maids would be waiting to hear the particular rumble of their cart and her father crying, ‘Whoa,’ to encourage Nell to stop. They seemed to be able to distinguish his cart from that of the coal merchant or the various pedlars, and would soon be lining up, jugs in hand, for supplies to see the households through the day.

Molly had marvelled that their wealthier customers could get through such a quantity of milk until Aunt Jane had told her they were in the habit of making junket and all manner of milky desserts that were served at dinner. Uncle William and Aunt Jane were sometimes invited to dine at the grand houses in Hawley Square, in view of William’s position as a trustee at the poorhouse, and so were well qualified to comment. The poorhouse, at William’s behest, had become a customer of the Goodchild Brothers milk business, following his assertion that milk would be good for undernourished children’s bones.

Molly had to admit to a grudging admiration for her uncle’s business sense. If he hadn’t seen an opportunity to grow his milk business, her job would have involved more than just milking the cows. She would have been expected to carry full pails up the hill, suspended from a great wooden yoke across her shoulders, then to hawk the milk around town. She was lucky to have the relatively respectable role of selling milk from the churn kept in the yard for those who couldn’t afford to pay for the convenience of the deliveries.

Molly had gone to fetch her book and pencil to keep account of those who preferred to settle their bill at the end of the week, when she saw that Charlie had seized the pitchfork and was setting about mucking out the stable.

‘Have you come from …’ She let the question hang in the air. Everyone locally called it the poorhouse although its name, Prospect House, suggested that those who entered its doors would receive the basic help required to set them on the path to a more secure future. The destitute were offered a dormitory bed, a uniform and a diet consisting mainly of soup, stew and potatoes, with meat on a Sunday after church, which all except the very sick must attend. Children who grew up in the poorhouse were expected to be apprenticed at seven or eight years old, the boys to a farmer or maltster, or as a sailor, the girls to the bakers, laundries and milliners of the town. Charlie, if he was a poorhouse boy, should surely be apprenticed to a trade at his age and not available to work in their yard.

Molly realised that Charlie had paused, hands folded over the top of the pitchfork handle, and was regarding her with deep brown eyes that held the hint of a smile.

‘Am I a Prospect boy, d’you mean? Aye,’ he said cheerfully. ‘Did your uncle not tell you? My brother Samuel is too poorly to come.’ Here Charlie’s face took on a sombre expression. ‘So I’m here in his stead. Just until he’s well again.’ Molly had a feeling that his words were more to convince himself than her. A cough such as his brother had could spread quickly through the poorhouse, carrying off the weak, the young and the old.

‘Nature’s way of limiting things,’ her uncle said briskly, whenever Sunday service at St John’s ended with prayers for a list of names from Prospect House, all of whom had succumbed to ailments that week.

‘Samuel,’ Molly repeated, aware that neither she nor her father had troubled to enquire about his name. Now that he had one, his health seemed more of a concern. ‘I hope he makes a quick recovery.’

Further conversation was prevented by the arrival of the first of a regular stream of local customers, and it was only when this had dwindled that Molly was able to question Charlie a little more. He’d finished and was scrubbing his hands at the pump. Realising how hungry she was, and how long she had been up and working, with just a mug of milk to sustain her, she unwrapped the hunk of bread and cheese her father had brought in and left for her in his office as usual.

‘Would you like some?’ she asked Charlie. Without being asked, he’d not only mucked out the stable but had somehow restored order to the yard. He’d stacked boxes and hung up various implements that Molly and her father had left out, intending to deal with them at some point.

Charlie hesitated, as if wondering whether she really meant it.

‘Go on,’ she urged. Within the hour she would be going home, with whatever milk was left in the churn, and she could be sure of a hot dinner shortly after that. Charlie looked as though he barely saw enough food to keep his bones covered with flesh, although there was no doubting that he was strong.

Molly halved the bread and cheese as well as she could and handed his portion to him. ‘What do you do?’ she asked. ‘Usually, I mean.’

‘I work in the poorhouse gardens,’ Charlie said, speaking through a mouthful of bread. He swallowed hard. ‘I’m apprenticed to the head gardener there, although I’ve barely another month to go.’ He bit into the bread again and chewed thoughtfully. ‘I’m one of the lucky ones. I love what I do and Mr Fleming has said that if he can’t keep me there he’ll find a garden to take me on his recommendation.’

Molly noticed that he’d pocketed all but a fragment of the cheese, which he now ate with the last morsel of bread.

‘Mr Fleming is good to me. He let me come here today so that Samuel could rest. Samuel will take over my apprenticeship when I’m done.’

Another customer arrived and Molly hurried to serve her, asking how her son fared, newly away to sea. When she turned back to Charlie, he was already on the other side of the gate.

‘Will we see you tomorrow?’ she called.

‘Aye, if Samuel’s no better,’ he replied. He waved and was gone before she could thank him. As Molly tipped the churn to empty the dregs into a metal can to take home, she thought about the two boys she had met that day, both strangers to her. It was unusual in a town where so much was routine, day after day and season after season.

An hour after Molly had arrived home, her father returned from his rounds. He came straight up to her in the kitchen as she stirred the stew for dinner.

‘I must thank you for the job you did on the yard,’ he said, clasping her shoulders and giving them a squeeze. ‘It hasn’t looked so clean and tidy in a long time. Your uncle stopped by as I was stabling the horse and he was most impressed.’

Molly blushed. ‘Oh, it wasn’t me. I can claim no credit. It was Charlie.’

‘Charlie?’ Her father paused in washing his hands and turned to her, puzzled.

‘The boy who helped load the churns this morning,’ Molly said. ‘He wasn’t a customer at all.’ She started to explain about Charlie’s younger brother Samuel to her father, until Ann called them to the table and her father’s attention was diverted by Lizzie and Mary.

Molly was to see Charlie each day over the next week, even on Sunday, when she could pick him out among the congregation in the pews at the back reserved for the poor-house inmates. There was no sign of Samuel at his side, and he’d had little good news to report each morning. Samuel struggled to eat or sleep, being plagued by coughing fits, and Charlie, who had no family in the poorhouse other than his brother, was clearly very worried.

Molly had learnt a little more about Charlie in snatched conversations while they both worked in the stable-yard. He’d arrived at the poorhouse with his mother, when he was six. His father had been lost at sea and his mother, expecting Samuel, had had no means of taking care of herself and her family. Charlie had been separated from his mother on arrival and put into a dormitory with the other boys. Having lived until then with mostly just his mother for company, Charlie had found Prospect House hard to bear. His mother had survived Samuel’s birth by less than a twelvemonth and Charlie had become his little brother’s protector. He stated these facts with very little emotion, but his words created a vivid picture for Molly. He went on to describe how he had started to hide in the poorhouse garden whenever he could as an escape from the place he now had to call home.

It hadn’t taken long for Mr Fleming, the head gardener, to notice Charlie lurking among the currant bushes but he’d chosen to ignore him. He’d worked in the walled garden as though Charlie wasn’t there, but after a couple of days, during which Charlie always slipped away to his dormitory at night but crept back at the first opportunity each morning, Mr Fleming had begun to talk to him as he worked. He’d told him what he was doing and why, as he’d staked up straggling plants or raked over the soil in the borders ready to sow seeds. He’d taken care not to catch Charlie’s eye or to address him directly, but Charlie had watched and listened.

After a week, his curiosity had got the better of him. He edged out from under the bushes to ask Mr Fleming why the trees had grown flowers. The head gardener’s answer was followed by a whole stream of questions that Charlie had obviously been storing up. Mr Fleming must have spoken to the authorities, for no one queried Charlie’s absences each day, and soon he and Charlie had become inseparable around the garden. On Charlie’s seventh birthday he found himself summoned to the overseer’s office.

‘Now, Charlie,’ Mr Dalton said, ‘I have something for you.’ Mr Fleming was also there, hands and face scrubbed and looking a little cleaner and tidier than usual. He nodded encouragingly at Charlie as Mr Dalton said, ‘I want you to make your mark on these papers here, to signify that you are apprenticed to Mr Fleming for the next seven years. Do you understand what this means, Charlie?’

Charlie nodded, for Mr Fleming had spoken to him about this. He was a little overawed by the seriousness of the occasion but made his cross on the page as asked, then went about the rest of his day in the garden as usual. He had been working with Mr Fleming ever since.

A week and a day after she had first met him, when Molly was checking the stable-yard gate every few minutes for signs of Charlie, another figure appeared. He was smaller than Charlie but taller than Samuel, and dressed in the Prospect House uniform. The boy introduced himself as Mark, but Molly was barely listening.

‘Charlie isn’t coming today?’ she asked him.

‘No, miss.’

‘Why. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...